Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Research Question 1: Which innovation strategies can Iranian digital music distributors adopt in order to reach a competitive advantage over their local and international competitors?

- Research Question 2: What are the main challenges for local music download shops in Iran and how might they deal with these dilemmas?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Digital Music Market in Iran

2.2. Competitive Advantage

2.3. Media Innovation

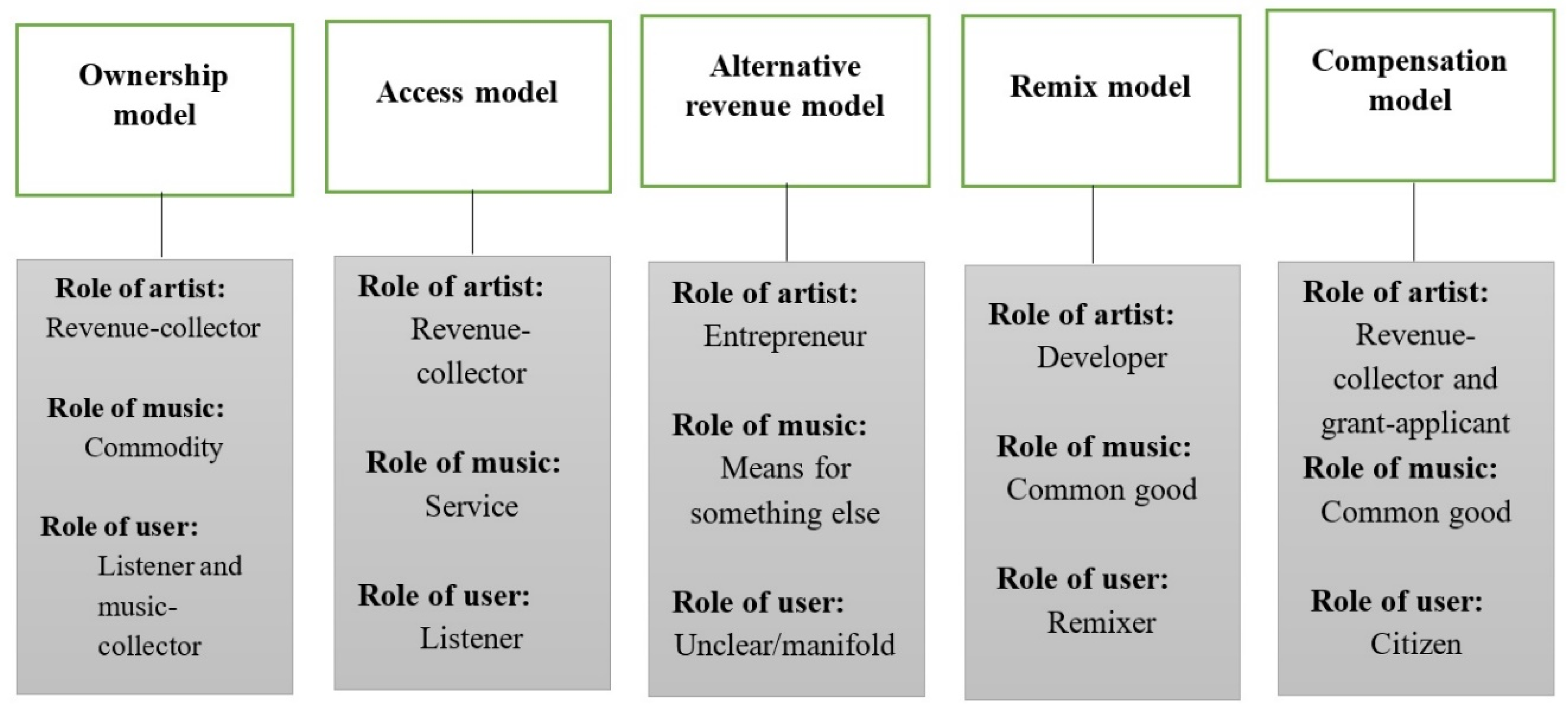

2.4. Music Distribution in the Digital Age

3. Method

4. Results and Discussion

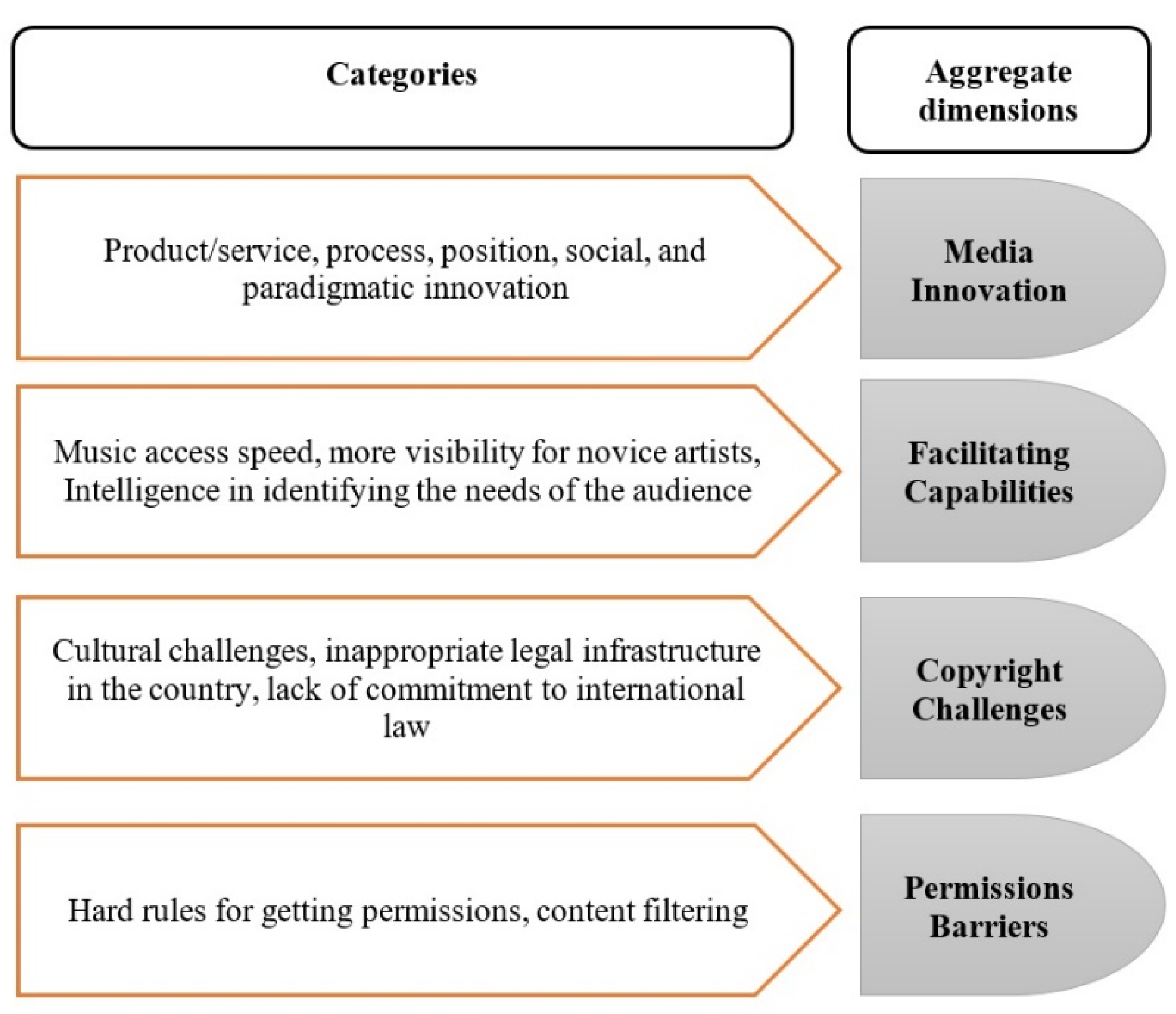

4.1. Media Innovation

4.2. Facilitating Capabilities

4.3. Copyright Challenges

4.4. Permissions Barriers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sousa, M.J.; Rocha, Á. Skills for disruptive digital business. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbatani, T.R.; Norouzi, E.; Omidi, A.; Valero-Pastor, J.M. Competitive strategies of mobile applications in online taxi services. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, G.P.; Hutchison, T.W.; Strasser, R. The Music Business and Recording Industry: Delivering Music in the 21st Century; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arbatani, T.R.; Asadi, H.; Omidi, A. Media Innovations in Digital Music Distribution: The Case of Beeptunes.com. In Competitiveness in Emerging Markets; Khajeheian, D., Friedrichsen, M., Modinger, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 93–108. ISBN 9783319717227. [Google Scholar]

- Tschmuck, P. From record selling to cultural entrepreneurship: The music economy in the digital paradigm shift. In Business Innovation and Disruption in the Music Industry; Wikström, P., DeFillippi, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.: Northampton, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Eiriz, V.; Leite, F.P. The digital distribution of music and its impact on the business models of independent musicians. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J.R.; Ogden, D.T.; Long, K. Music marketing: A history and landscape. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. The Death and Life of the Music Industry in the Digital Age; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kjus, Y. Reclaiming the music: The power of local and physical music distribution in the age of global online services. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 2116–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjus, Y. Live and Recorded: Music Experience in the Digital Millennium; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro, V.L.; Cohn, D.Y. The evolution of business models and marketing strategies in the music industry. Int. J. Media Manag. 2004, 6, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, K.; Watanabe, C.; Neittaanmäki, P. Co-evolution between streaming and live music leads a way to the sustainable growth of music industry—Lessons from the US experiences. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, D. ITunes: Breaking barriers and building walls. Pop. Music Soc. 2014, 37, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hracs, B.J.; Jakob, D.; Hauge, A. Standing out in the Crowd: The Rise of Exclusivity-Based Strategies to Compete in the Contemporary Marketplace for Music and Fashion. Environ. Plan. A Econ. 2013, 45, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Mourali, M. Effect of peer influence on unauthorized music downloading and sharing: The moderating role of self-construal. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFPI. Global Music Report; International Federation of the Phonographic Industry: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, G. Innovation in the Use of Digital Infrastructures. In Media Innovations: A Multidisciplinary Study of Change; Storsul, T., Krumsvik, A.H., Eds.; NORDICOM: Göteborg, Sweden, 2013; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Pourghannad, S. History of Entring Music to Internet. Available online: http://www.harmonytalk.com/id/1245%0D%0A (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Virgool Beeptunes: We are Afraid of Seeing! Available online: https://b2n.ir/298871 (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Parsapour, A. An End to the Illegal Download of Music in Iran! Available online: https://dgto.ir/q-4 (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Beygzadeh, A. The Filter of SoundCloud is Removed in Iran! Available online: https://dgto.ir/pu8 (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- GOV.IR. List of Music Companies and Active Studios in Iran. Available online: https://music.farhang.gov.ir/fa/companies/companies (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- PANA. Statistics of Music in 2017. Available online: http://www.pana.ir/news/806687 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- GOV.IR. Music Report (Song Tracks). Available online: https://honari.farhang.gov.ir/fa/mojavezha/daftaremosighi/takahang (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- GOV.IR. Music Report (Full Album). Available online: https://honari.farhang.gov.ir/fa/mojavezha/daftaremosighi/album (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Na, Y.K.; Kang, S. Effects of core resource and competence characteristics of sharing economy business on shared value, distinctive competitive advantage, and behavior intention. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.W.L.; Jones, G.R.; Schilling, M.A. Strategic Management: Theory: An Integrated Approach; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maury, B. Sustainable competitive advantage and profitability persistence: Sources versus outcomes for assessing advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K. The Cores of Strategic Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, W.-Y. Enhancing competitive advantages: The contribution of mediator and moderator on stickiness in the LINE. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Ogbonna, E. Competitive advantage in the UK food retailing sector: Past, present and future. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Contemporary Strategy Analysis: Text and Cases Edition; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rothaermel, F.T. Strategic Management; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.S.; Linderman, K. Resource-Based Product and Process Innovation Model: Theory Development and Empirical Validation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Ardito, L. Firm Size and Sustainable Innovation Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The creative response in economic history. J. Econ. Hist. 1947, 7, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.N.; Bahram, N. The hypercube of innovation. Res. Policy 1995, 24, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, T.; Epstein, M.; Shelton, R. Making Innovation Work: How to Manage it, Measure It, and Profit from It; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Volberda, H.W.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Heij, C.V. Management innovation: Management as fertile ground for innovation. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortt, J.R.; van der Duin, P.A. The evolution of innovation management towards contextual innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 11, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.I.; Markuerkiaga, L. Application of Innovation Management Techniques in SMEs: A Process Based Method. In Closing the Gap Between Practice and Research in Industrial Engineering; Lecture Notes in Management and Industrial, Engineering; Viles, E., Ormazábal, M., Lleó, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-3-319-58408-9. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, S. Adapting to the brave new world: Innovative organisational strategies for media companies. In Media Innovations a Multidisciplinary Study of Change; Nordicom: Göteborg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, H.; Sund, K.J. The journey of business model innovation in media agencies: Towards a three-stage process model. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2018, 14, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murschetz, P.C.; Omidi, A.; Oliver, J.J.; Saraji, M.K.; Javed, S. Dynamic Capabilities in Media Management Research: A Literature Review. J. Strateg. Manag. 2020, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Mierzjewska, B.I. Theoretical approaches in media management research revised. In Handbook of Media Management and Economics; Albarran, A.B., Mierzjewska, B.I., Jung, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goffin, K.; Mitchell, R. Innovation Management: Effective Strategy and Implementation, 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baregheh, A.; Rowley, J.; Sambrook, S. Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J. Innovation management in context: Environment, organization and performance. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2001, 3, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storsul, T.; Krumsvik, A.H. What is media innovation? In Media Innovations: A Multidisciplinary Study of Change; Storsul, T., Krumsvik, A.H., Eds.; NORDICOM: Göteborg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mierzjewska, B.I.; Hollifield, C.A. Theoretical approaches in media management research. In Handbook of Media Management and Economics; Albarran, A.B., Chan-Olmsted, S.M., O.Wirth, M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.W. Innovation Management and U.S. Weekly Newspaper Web Sites: An Examination of Newspaper Managers and Emerging Technology. Int. J. Media Manag. 2008, 10, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvie, G.; Schmitz Weiss, A. Putting the Management into Innovation & Media Management Studies: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Media Manag. 2012, 14, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Zotto, C.; Van Kranenburg, H. Management and Innovation in the Media Industry; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Küng, L. Innovation, Technology and Organisational Change. In Media Innovations: A Multidisciplinary Study of Change; Storsul, T., Krumsvik, A.H., Eds.; NORDICOM: Göteborg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Westlund, O.; Lewis, S.C. Agents of media innovations: Actors, actants, and audiences. J. Media Innov. 2014, 1, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomborg, S.; Helles, R. Privacy in practice: The regulation of personal data in Denmark and its implications for new media innovation. In Media Innovations: A Multidisciplinary Study of Change; Storsul, T., Krumsvik, A.H., Eds.; NORDICOM: Göteborg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dogruel, L. What is so special about media innovations? A characterization of the field. J. Media Innov. 2014, 1, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruel, L. Innovation research in media management and economics: An integrative framework. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2015, 12, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, R.A. Media innovation: Three Strategic Approaches to Business Transformation. In Handbook of Media Management and Economics; Alan, B., Albarran Bozena, I., Mierzejewska, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Krumsvik, A.H.; Milan, S.; Bhroin, N.N.; Storsul, T. 14. Making (Sense of) Media Innovations. In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions; Deuze, M., Prenger, M., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, D.; Bessant, J. Targeting innovation and implications for capability development. Technovation 2005, 25, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lara González, A.; Arias Robles, F.; Carvajal Prieto, M.; García Avilés, J.A. Ranking de innovación periodística 2014 en España. Selección y análisis de 25 iniciativas. El Prof. Inf. 2015, 24, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero Pastor, J.M. Tendencias de la innovación mediática en Estados Unidos. Miguel Hernández Commun. J. 2015, 7, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. Digital Revolution Tamed: The Case of the Recording Industry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-93021-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nordgård, D. The Music Business and Digital Impacts; Music Business Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-91886-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, G.; Tinson, J. Psychological ownership and music streaming consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.R.; Brennan, M.; McAdam, R. A rewarding experience? Exploring how crowdfunding is affecting music industry business models. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, H.S. Digital Music Distribution: The Sociology of Online Music Streams; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Tradition; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brower, R.S.; Jeong, H. Grounded analysis: Going beyond description to derive theory from qualitative data. Public Adm. Public Policy N. Y. 2008, 134, 823. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, J.A. The coding process and its challenges. In The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. In Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsch, V. Qualitative research: A grounded theory example and evaluation criteria. J. Agribus. 2005, 23, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Parsapour, A. A global attemp to remove illegal downloading of Iranian music. Available online: https://b2n.ir/402063 (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- GOV.IR. The Investigation form of Audio Products. Available online: https://music.farhang.gov.ir/fa/form/bakhsheherasat/albom (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Lashkari, V. Our Music. Available online: http://www.musicema.com/node/300722 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- YJC Licensing of a Rap Music. Available online: http://www.khabaronline.ir/news/536080 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Khabaronline is Singing Women Forbidden? Viewponts of Ayatullah Khamenei and Makarem. Available online: http://www.khabaronline.ir/news/320418 (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Elmjouie, Y. Alone Again, Naturally: Women Singing in Iran. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2014/aug/29/women-singing-islamic-republic-iran (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Khajeheian, D.; Tadayoni, R. User innovation in public service broadcasts: Creating public value by media entrepreneurship. Int. J. Technol. Transf. Commer. 2016, 14, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeheian, D. New venture creation in social media platform; towards a framework for media entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Social Media Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Khajeheian, D.; Friedrichsen, M. Innovation Inventory as a Source of Creativity for Interactive Television. In Digital Transformation in Journalism and News Media; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström, P. A typology of music distribution models. Int. J. Music Bus. Res. 2012, 1, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Towse, R. Copyright and Music Publishing in the UK. In The Artful Economist; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, M. Copyright culture and pirate politics. Cult. Stud. 2014, 28, 1022–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, M.W. Social innovation capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.; Herrera, M.E.B.; Googins, B.; Albareda, L. Corporate social innovation: How firms learn to innovate for the greater good. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5014–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, F. The emancipatory role of information and communication technology: A case study of internet content filtering within Iran. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2010, 8, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, D.; Goold, J. Iran and the emergence of information and communications technology: The evolution of revolution? Aust. J. Int. Aff. 2014, 68, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameripour, A.; Nicholson, B.; Newman, M. Conviviality of Internet social networks: An exploratory study of Internet campaigns in Iran. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Interviewee Code | Main Activity | Educational Experiences | Professional Experiences | Interview Length (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1ASH | Music artist | M.A. student in management | More than six years of experience in conducting live music performances | 66 |

| 2 | 2MP | Music artist | M.A graduated in engineering | Publishing several professional songs on famous Iranian music websites | 43 |

| 3 | 3HS | Digital music industry professional | Ph.D. candidate in sociology | Music expert in the Ministry of Culture | 59 |

| 4 | 4ESH | Digital music industry professional | Diploma | Founder and CEO in a music company | 35 |

| 5 | 5AMSH | Digital music industry professional | B.A. in Arts | Marketing manager in a digital distribution service | 92 |

| 6 | 6FH | Digital music industry professional | Ph.D. in engineering | Founder and CEO in a digital music distribution service | 37 |

| 7 | 7MJ | Media researcher | M.A student in media management | Consultant and researcher in the field of digital business | 79 |

| 8 | 8EN | Media researcher | M.A student in media management | Consultant and researcher in the field of digital business | 60 |

| 9 | 9JN | Media researcher | Ph.D. in media management | Consultant and researcher in the field of digital business | 92 |

| 10 | 10DKH | Media researcher | Ph.D. in media management | Faculty member and researcher in the field of digital business | 48 |

| 11 | 11SHJ | Business researcher | Ph.D. candidate in strategic management | Strategy consultant and researcher in digital business | 60 |

| 12 | 12SS | Media researcher | Ph.D. in media management | Faculty member and researcher in the field of digital business | 52 |

| 13 | 13RS | Digital music industry professional | MBA graduated | Founder and CEO in a music company | 66 |

| 14 | 14SL | Media researcher | Ph.D. in media management | University lecturer and researcher in digital business | 45 |

| Media Innovation Categories | Key Innovative Strategic Actions | Evidence from Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Product/service | Preservation of musical identity in the presentation of new products | “Product innovations in the digital distribution of music must be such as to preserve their musical identity and not move musical works to non-musical works since in this way the target audience will generally change, and the business will face serious challenges” (10DKH). |

| Product offer based on customer’s mood | “Before we can create a new product, we need to design a mechanism to match the best product to the audience’s mood, for example, to create a product that can be played by giving the keyword of the song you want” (9JN). | |

| A special presentation of new talent works | “Introducing products of music talents (new faces) to people, and these new talents will improve their work in the future” (8EN) | |

| Selling products in a package form | “The audience is interested in the package. If we can make a package of products, it can be useful” (7MJ). | |

| Selling related products | “You can sell items related to an album, such as bracelets and necklaces that are related to them (artists), or you can sell their concert tickets” (5AMSH). | |

| Selling playlists of celebrities | “You can make a list of famous singers, what songs your favorite singer listens to” (10DKH). | |

| Leveling products based on professional criteria | “For example, according to professional standards, we level the products. These categories make the producers more careful about quality” (1ASH) | |

| Music-by-order | “We can have digital services in music that we can order for ourselves to the production of a special music, either for a person or organization and even for special occasions like weddings” (11SHJ). | |

| Process | Simplify the purchase process | “I think it would be possible for the audiences to buy their favorite music in a simpler way” (1ASH). |

| Attention to customer experience | “There should be some way to increase shopping pleasure. Now it’s specialized: cheaper, faster, and better quality” (7MJ). | |

| Preview products in the buying process | “We have thirty seconds previews, which most artists give us to tell us which part of it is better. Sometimes our musicians do it” (5AMSH). | |

| Pay attention to aesthetic issues in the buying process | “If we consider this business as a store, where products are offered by graphical designs, then designing a website template is very important in terms of graphics and aesthetic issues” (1ASH). | |

| Position | Accurate analysis of competitors | “One version cannot be packed for every business and instead, depending on the competitors’ analysis, each business requires its own strategy” (2MP). |

| Strategic alliances with other businesses | “For example, a music download store would be positioned in the minds of the people if it can be possible to find its own related businesses and engage in strategic partnerships with them” (2MP). | |

| Pay attention to niche markets | “We should try to identify the niche markets that others have not worked on (for example, just create a market for artists and musicians), and we will set the standards ourselves” (8EN). | |

| Paradigmatic | Free from copyright | “The digital business model in the future will completely break copyright law and go for free. Instead, attracting the attention of the audience will be the most important factor in success” (12SS). |

| Simplifications in music access | “Technology is becoming more sophisticated and the presentation of products is becoming simpler. Perhaps there is another stage in which these tools will be reduced and there will no longer be a need for a device such as a phone or a tablet. Therefore, if we care about changing the paradigm, we should think about simplifications” (1ASH) | |

| Social | Create space for critical dialogue | “The topic of discussion is also very important. Bringing the subject of discussion and bringing people together for creating a critical dialogue and challenge” (7MJ). |

| Holding real events | “Also, these businesses can, at some point, hold real events and bring their audience together in a real world” (10DKH) | |

| Encouraging the audience to create content | “Encouraging the audience to create content and become part of the music production system” (2MP). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omidi, A.; Dal Zotto, C.; Norouzi, E.; Valero-Pastor, J.M. Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062381

Omidi A, Dal Zotto C, Norouzi E, Valero-Pastor JM. Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062381

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmidi, Afshin, Cinzia Dal Zotto, Esmaeil Norouzi, and José María Valero-Pastor. 2020. "Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062381

APA StyleOmidi, A., Dal Zotto, C., Norouzi, E., & Valero-Pastor, J. M. (2020). Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran. Sustainability, 12(6), 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062381