The Influence of Traditional Cultural Resources (TCRs) on the Communication of Clothing Brands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional Cultural Resources

2.1.1. The Meaning of Traditional Cultural Resources

2.1.2. Sign Differentiation of Traditional Cultural Resources

2.2. Brand Culture

2.3. Brand Communication

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Method Selection and Case Selection

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Part One

3.3.2. Part Two

4. Case Description and Analysis

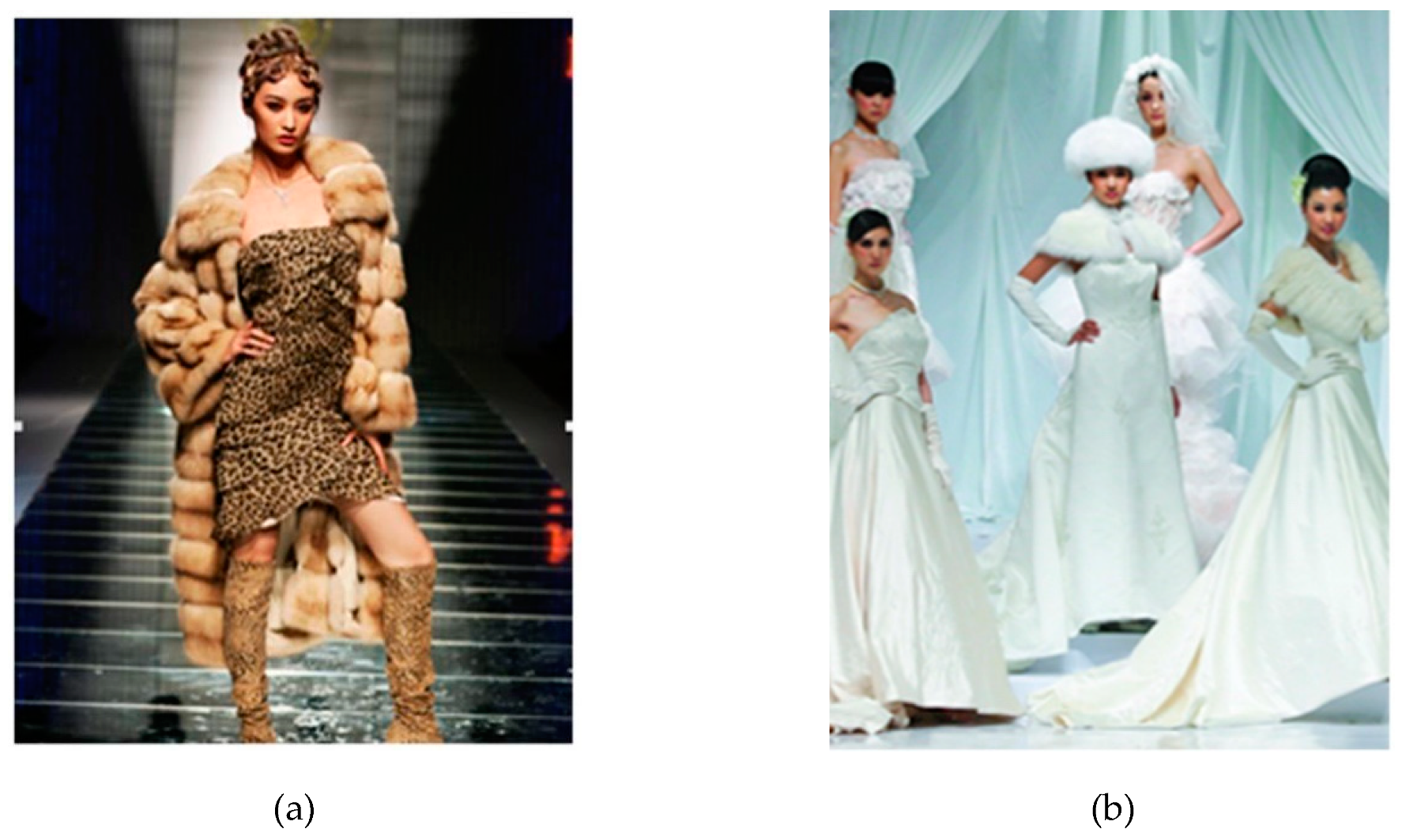

4.1. Pre-Adoption: 1982–2005

4.2. Post-Adoption 2006–2018

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Brand Culture Shift Function

5.2. Academic Cohesion Function

5.3. Social Connection Function

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Significance

6.2. Practical Implication

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.L.; Shen, H.; Dong, W.M. How to Promote New Products—An Empirical Study on the Relationship among Marketing Strategies. Mod. Ecol. Sci. 2015, 03, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, T. The Globalization of Markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1983, 61, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.M.; Cavusgil, S.T. Global Strategy: A Review and an Integrated Conceptual Framework. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q. Status and Development of Domestic Clothing Brands. Available online: https://www.ixueshu.com/document/e4859208ffe87b813131004f433870b9318947a18e7f9386.html (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Zhai, H.H. Research on the Status and Countermeasures of Chinese Clothing Brands. Market. Weekly. 2008, 10, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Du, Q.P.; Yu, J.Y.; Li, H. Research on the Value of Chinese Clothing Brands: Continental Plate Panorama; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J. Fashion Brands: Branding Style from Armani to Zara. J. Pop. Cult. 2006, 39, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A.; Choy, E. Studying Chinese Generation Y Consumers’ Involvement Infashion Clothing and Perceived Brand Status. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. How to Build Clothing Marketing and brand Planning. Chinese Nat. Expo. 2017, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Market. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L. Research on Brand Culture and Design Orientation of Local Independent Fashion Designers. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFDLAST2019&filename=LLSC201901004&v=MjIzMDlPZG5GeXpsVXI3T0tTSFliYkc0SDlqTXJvOUZZSVI4ZVgxTHV4WVM3RGgxVDNxVHJXTTFGckNVUjdxZlo= (accessed on 2 January 2020). (In Chinese).

- Aaker, J.; Fournier, S.; Brasel, S.A. When Good Brand Do Bad. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.D.; Shu, X.P.; Lu, H.L. Cultural Standpoint of Design: A Study of the Discourse Right of Chinese Design; Jiangsu Phoenix Fine Arts Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. Research on the Sign Image of Costume Visited by Peng Liyuan——Based on the Perspective of Communication. Master’s Thesis, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, H.Y. A Study on the Impact of Chinese Brand Local Symbolic Value on Purchase Possibility. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 24, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Brand Equity and Advertising; Biel, A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A. Brand Communications in Fashion Categories Using Celebrity Endorsement. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 17, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.M.; Zhu, J.D.; Xiao, J.S. Brand Communication, 2nd ed.; Shanghai Jiaotong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.C.; Liu, L.X.; Cui, Y. A Study on Consumers’ Preferences for the Palace Museum’s Cultural and Creative Products from the Perspective of Cultural Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Song, Y.; Tian, Y. The Impact of Product Design with Traditional Cultural Properties (TCPs) on Consumer Behavior Through Cultural Perceptions: Evidence from the Young Chinese Generation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, R. Analysis of Chinese Traditional Cultural Tradition Clothing Brands. Fashion. Guide 2018, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board of Cihai, Cihai (An Unabridged, Comprehensive Dictionary), 6th ed.; Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2009; p. 321.

- Yi, J.Q. Fifteen Lectures on Cultural Philosophy; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage-Questions and Answers. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01855-EN.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Yin, Y.T. A Study on the Change of Chinese Contemporary Brand Culture Transmission—Based on the Perspective of Advertising Communication (1978–2015). Ph.D. Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- David, T. Economics and Cultural, 1st ed.; Art and Collection Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2003; pp. 33–39. ISBN 9789572832. [Google Scholar]

- The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Central Compilation and Translation Bureau. Selected Works of Marx and Engels, 2nd ed.; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1995; Volume IV, p. 373. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Z. Application of Bamboo Resources in Environmental Art Design. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqin, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.P. From Cultural Resources to Cultural Capital: The Value Reconstruction and Re-creation of Traditional Culture. J. Vis. Cult. 2007, 06, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 1978; ISBN 9780253202178. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.Y. Traditional Handicraft in Traditional Chinese Culture. J. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2011, 05, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, L.; Chris, S. Making as Growth: Narratives in Materials and Process. Des. Issues 2017, 33, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudrillard, J. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, 1st ed.; Zhang, Y.B., Zhou, X., Ren, T.S., Eds.; Nanjing University Press: Nanjing, China, 2001; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Mythologies; Guiguang Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 1998; ISBN 9789575519896. [Google Scholar]

- Debord, G. Society of the Spectacle, 4th ed.; Zhang, X.M., Translator; Nanjing University Press: Nanjing, China, 2018; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J.; Borgerson, J.; Wu, Z.Y. A Brand Culture Approach to Brand Literacy: Consumer Co-Creation and Emerging Chinese Luxury Brands. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2511638 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Li, G.D. Brand Competitiveness; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, J.C.; McDonagh, P. Consumer Roles in Brand Culture and Value Co-Creation in Virtual Communities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdu-Jover, A.J.; Alos-Simo, L.; Gomez-Gras, J.M. Adaptive Culture and Product/Service Innovation Outcomes. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Cui, Z.Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, N. Brand Revitalization of Heritage Enterprises for Cultural Sustainability in the Digital Era: A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Jaishankar, G.; Echambadi, R. Crossnational Diffusion Research: What Do We Know and How Certain Are We? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1998, 15, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, G. Converging Trends within the European Union: Insights from an Analysis of Diffusion Patterns. J. Int. Mark. 1998, 6, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, L.R. Developing Brand Literacy among Affluent Chinese Consumers: A Semiotic Perspective. Adv. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kates, S.M. Researching Brands Ethnographically: An Interpretive Community Approach. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing; Russell, W.B., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J.E. The Cultural Codes of Branding. Mark. Theory 2009, 9, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, A.; Fuat Fırat, A. Brand Literacy: Consumers’ Sense-making of Brand Management. Adv. Consum. Res. 2006, 33, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chinomona, R. Brand Communication, Brand Image and Brand Trust as antecedents of Brand Loyalty in Gauteng Province of South Africa. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2016, 7, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, C.; Şahin, A.; Kitapci, H.; Özşahin, M. The Effects of Brand Communication and Service Quality in Building Brand Loyalty through Brand Trust; The Empirical Research on Global Brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.T.; Li, Y.J. Communication Model of Agricultural Resources Brand under Different Trust Orientation. Chin. J. Manag. 2015, 12, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, N.Y.; Wang, Y. Research on Theoretical Model of Brand Communication Mode. Chin. J. Ergon. 2010, 16, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N. Brand Communication Literature and Theory Development Research for Nearly 10 Years. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass, A.; Siahtiri, V. Are Young Adult Chinese Status and Fashion Clothing Brand Conscious? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2014, 18, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Flynn, L.R.; Clark, R.A. Materialistic, Brand Engaged and Status Consuming Consumers and Clothing Behaviors. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.; Diamond, E. Fashion Advertising and Promotion; Fairchild Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Analysis of Clothing Brand Communication Methods. Tianjin Text. Sci. Technol. 2016, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Methanuntakul, K. High-Street Fashion Brand Communication amongst Female Adolescents. Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University, London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Khan, M.A. Branding of Clothing Fashion products: Fashion Brand Image Development by Marketing Communication Approach. Res. J. Eng. Sci. 2013, 2, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.J. Analysis of Brand Media’s New Media Marketing Strategy in the Internet Environment. Fortune Today 2019, 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. J. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The Case Study Crisis: Some Answers. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.; Bateson, P. Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D.G. Manual for Scoring Motive Imagery in Running Text, 3rd ed.; Unpublished Manuscript; Department of Psychology, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.S.; Ruan, L.Y.; Wang, M.T.; Wang, L.T.; Li, P.L.; Gao, X.F.; Huang, L.C.; Huang, R.S.; Chen, S.C.; Chen, Y.Z.; et al. Design Research Methods; Quanhua Tech. In.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, M.N. Doing Survey Reaearch: A Guide to Quantitative Methods, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio, K.R.; Forehand, M.R. An Interpretive Frame Model of Identity-Dependent Learning: The Moderating Role of Content-State Association. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Cortes-Garcia, F.J.; Belmonte-Urena, L.J. The Sustainable Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheenagh, P. Cultural Research and Intangible Heritage. J. Cult. Unb 2009, 220, 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Culture for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/culture-and-development/the-future-we-want-the-role-of-culture/the-unesco-cultural-conventions/ (accessed on 25 February 2020).

| Interview Date | Name | Gender | Profession | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/09/23 | A-T | Female | Instructor | Fashion Illustration Advanced clothing customization |

| 2018/09/24 | B-F | Female | Professor | Clothing brand marketing Clothing psychology |

| 2018/10/12 | C-P | Male | Professor | Design thinking |

| 2018/10/28 | D-B | Male | Brand director | Brand vision management |

| 2018/10/28 | E-I | Female | Instructor | Clothing fabric Clothing accessories design |

| 2018/12/04 | F-B | Male | Brand director | Brand planning and promotion |

| 2018/12/12 | G-B | Female | Brand director | Brand commodity planning |

| 2019/01/28 | H-P | Female | Professor | Design aesthetics Clothing criticism |

| Encoder | Profession | Background |

|---|---|---|

| E-1 | National Yunlin university of science and technology Doctoral student | Design |

| E-2 | National Yunlin university of science and technology Masters student | Design media |

| E-3 | National Yunlin university of science and technology Doctoral student | Design |

| First Common Reliability | Second Common Reliability | Third Common Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| 0.281 | 0.673 | 0.710 |

| Classification | No. | Common Open Coding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural attribution orientation | 1 | You will only see the most authentic culture by focusing deeply on local goods | F-B/02/04 |

| 2 | Oriental aesthetics | H-P/01/12 | |

| 3 | The traditional culture ecology gives birth to the expression of the artistic conception form in local art | B-F/01/18 | |

| 4 | Eastern aesthetics often call a thing a “Tao-Qi” (道器) to represent our own philosophy | H-P/03/21 | |

| 5 | It carries people’s appeals to a particular culture | D-B/01/18 | |

| 6 | It is more accurate for Chinese people to utilize a Chinese style. The prevailing Chinese style is just a style, not a deeper culture marker | H-P/04/08-09 | |

| 7 | Local cultural landscape | C-P/03/02 | |

| 8 | National identity | A-T/01/19 | |

| Knowledge perception orientation | 9 | It contains very deep cognitive thoughts about the external world | C-P/02/17 |

| 10 | It is enlightening to think about modern design products, especially human-oriented design | G-B/01/11 | |

| 11 | From the objects, we can understand the truth of being a human being, and that the relationship between objects and people is shaped by each other | H-P/05/24-25 | |

| 12 | Traditional appliances come from the practice of life, so you can see the change of a lifestyle | C-P/03/27 | |

| 13 | The materials are used in an orderly way. Both the quality and the hard degree of the material need to receive attention | A-T/04/15 | |

| 14 | Viewing the museum relic is a way of recalling this relic | F-B/01/25 | |

| 15 | Although it is an intangible cultural heritage, through transformation it can conform to the current aesthetic | G-B/03/24 | |

| 16 | Students tend to study traditional fabrics when designing | E-I/02/14 | |

| Stakeholder orientation | 17 | Because traditional products are too laborious, they gradually change the way people view traditional things | G-B/04/16 |

| 18 | When you see exquisite art work, you think of the craftsmanship of each process | E-I/02/13 | |

| 19 | It is often given to foreign friends in the form of a national gift | F-B/04/23 | |

| 20 | Local creation | C-P/3/10 | |

| 21 | Generally, it is regional, just like Zhenhu in Suzhou, which is an embroidery cultural area | B-F/04/12 |

| First Common Reliability Result | Second Common Reliability Result | Third Common Reliability Result |

|---|---|---|

| 0.542 | 0.651 | 0.705 |

| Sign-Meaning | Transition Effect | Sign-Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural attribution orientation | From dependent to independent development | Brand culture shift |

| Knowledge perception orientation | Research and exchange platform of Chinese clothing culture | Academic cohesion |

| Stakeholder orientation | Single brand to social network | Social connection |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, K.-K.; Zhou, Y. The Influence of Traditional Cultural Resources (TCRs) on the Communication of Clothing Brands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062379

Fan K-K, Zhou Y. The Influence of Traditional Cultural Resources (TCRs) on the Communication of Clothing Brands. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062379

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Kuo-Kuang, and Ying Zhou. 2020. "The Influence of Traditional Cultural Resources (TCRs) on the Communication of Clothing Brands" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062379

APA StyleFan, K.-K., & Zhou, Y. (2020). The Influence of Traditional Cultural Resources (TCRs) on the Communication of Clothing Brands. Sustainability, 12(6), 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062379