The Corporate Shared Value for Sustainable Development: An Ecosystem Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background of the CSV Concept

2.2. The Wisdom of Corporate Shared Value

2.3. Theoretical Lens: Systems Thinking and the Ecosystem Perspective

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Selection and Overview

3.2. Data Description and Gathering

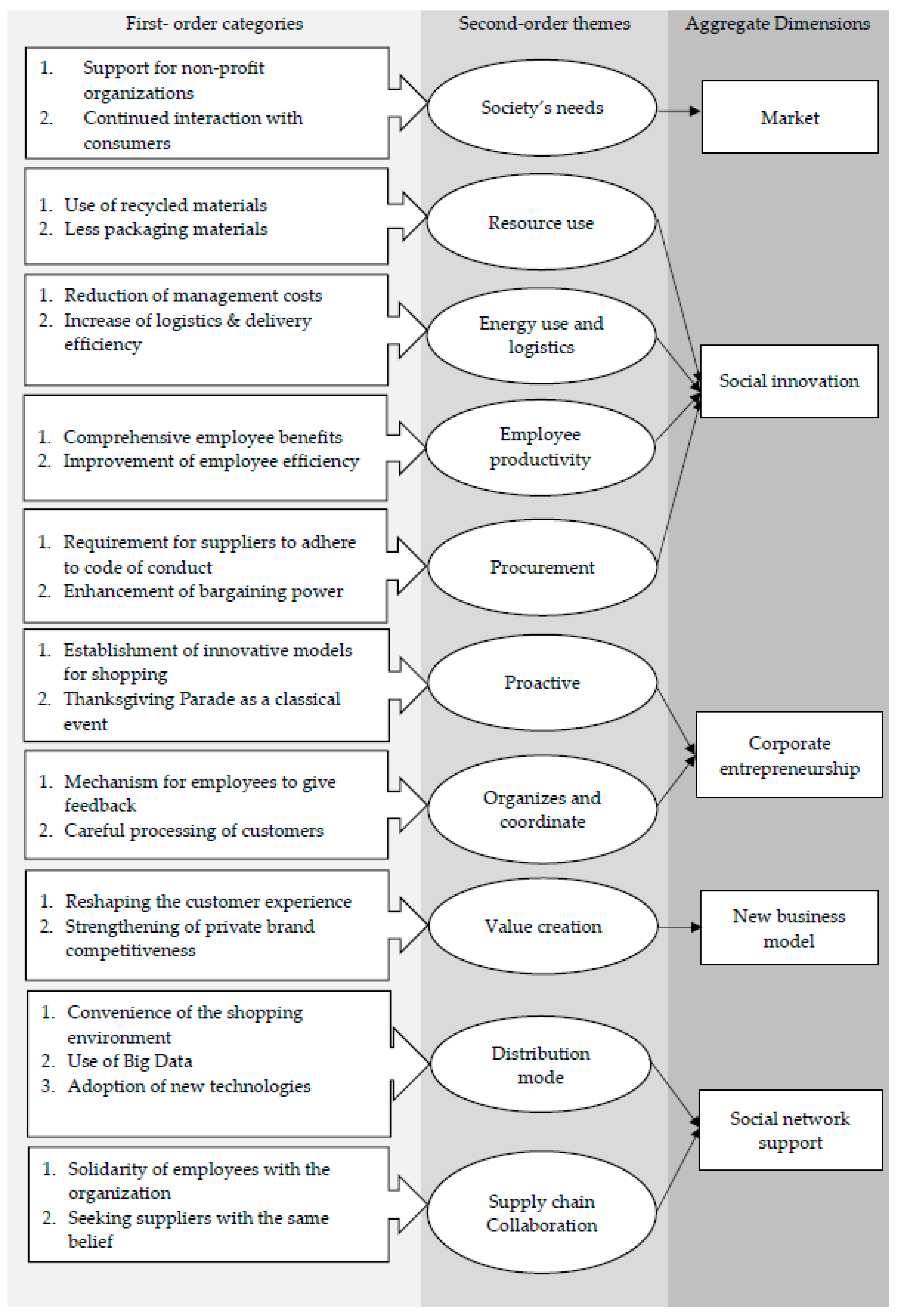

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

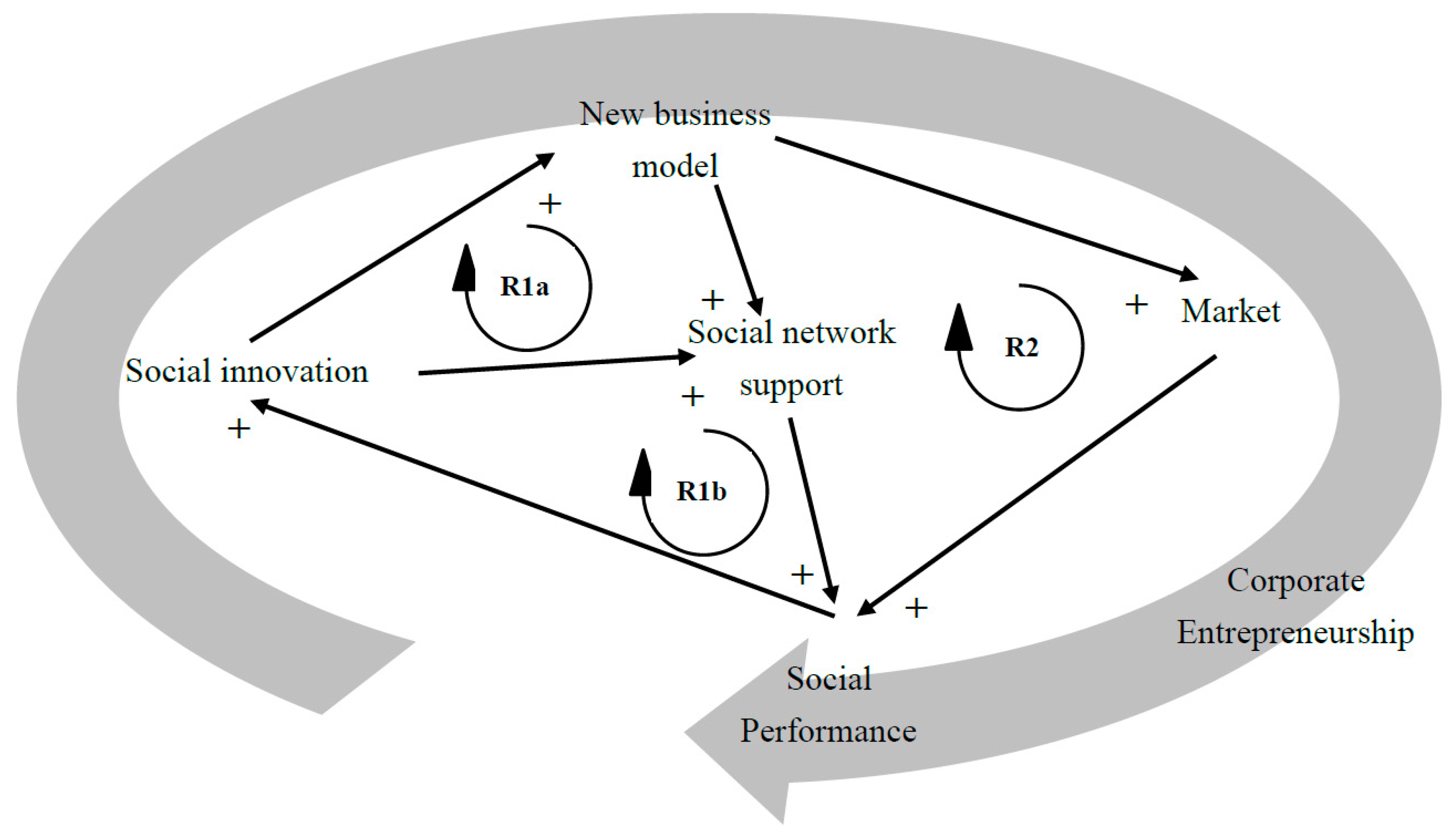

4. Research Findings

4.1. Loop 1: Business Models and Social Innovation Supported by Social Network

The increase in the use of solar energy and changing in-store lights into LED lightbulbs have enhanced the efficiency of our energy consumption. (Becky)

The support of special social groups speaks of Macy’s diversity and tolerance. This makes employees feel affiliated with the company they work for. (Amy)

In the past, one plastic bag was used for each garment. Now only one plastic bag is used for each box. Unless necessary, we do not use lining paper. (Amy)

Macy’s demands a lot from suppliers. If you can meet Macy’s standards, you do not need to worry about the requirements from other clients. (Ellen)

We have the algorithms to determine which branch to transfer inventory from in order to accelerate the delivery. We can even deliver on the same day, so that customers can order online and pick up their products in store. (Debby)

Our personnel attrition rate is low. While the benefits are not the best in the industry, most colleagues feel good working for the company. (Amy)

Macy’s insists on high quality at reasonable prices. The cost/performance ratio is high. Its dedication to sustainability, CSR, and supplier requirements are persuasive. I will apply the same standards when I shop. (Georgia)

4.2. Loop 2: The Connection of New Business Models and Markets Led the Social Performance

Make-A-Wish is one of Macy’s best-known social events. Many families look forward to it every year. (Amy)

Given the impact from ecommerce, Macy’s must enhance the customer experience by leveraging its bricks and mortars. (Cindy)

4.3. Role of Corporate Entrepreneurship in the CSV Ecosystem

On one occasion a pair of red pants lost its color and stained the light-colored sofa of a customer at home. The headquarter convened a meeting immediately to identify the problem and replace the material. (Amy)

Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade is a popular tradition in the U.S. A tradition created by Macy’s. (Fanny)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Germann, F.; Grewal, R. Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, J.; Kashmiri, S.; Mahajan, V. Signaling virtue: Does firm corporate social performance trajectory moderate the social performance–financial performance relationship? J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Schons, L.M.; Alavi, S.; Wieseke, J. Warm glow or extra charge? The ambivalent effect of corporate social responsibility activities on customers’ perceived price fairness. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, K.J.; Kwon, S.J. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of consumer loyalty: An examination of ethical standard, satisfaction, and trust. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Osburg, T.; Schmidpeter, R. (Eds.) Social Innovation: Solutions for a Sustainable Future; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the value of “Creating Shared Value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Coombs, J.E. The moderating effects from corporate governance characteristics on the relationship between available slack and community-based firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassch, O.; Yang, J. Rebuilding dynamics between corporate social responsibility and international development on the search for shared value. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 2011, 15, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboven, H. Communicating CSR and business identity in the chemical industry through mission slogans. Bus. Commun. Q. 2011, 74, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, A.; Fullerton, J.A.; Kim, Y.J. Social responsibility in advertising: A marketing communications student perspective. J. Mark. Educ. 2013, 35, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.L.; Dubois, D.A. Expanding the vision of industrial-organizational psychology contributions to environmental sustainability. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, P. How creating shared value differs from corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Bus. Adm. 2016, 24, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, K.; Singh, P.; Bhakoo, V. Literature review of shared value: A theoretical concept or a management buzzword? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. A response to Andrew Crane et al.’s article by Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- Awale, R.; Rowlinson, S. A conceptual framework for achieving firm competitiveness in construction: A’ creating shared value (CSV) concept. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual ARCOM Conference, Portsmouth, UK, 1–3 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.R.; Pfitzer, M.W. The ecosystem of shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.; Knudsen, J.S. Managing corporate responsibility globally and locally: Lessons from a CR leader. Bus. Politics 2012, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kennelly, J.J. Sustainability and place-based enterprise. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltz, E.; Thompson, F.; Ringold, D.J. Assessing and maximizing corporate social initiatives: A strategic view of corporate social responsibility. J. Public Aff. 2011, 11, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, M. Social entrepreneurs as the paragons of shared value creation? A critical perspective. Soc. Enterp. J. 2012, 8, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.; Ambrosini, V. Value creation versus value capture: Towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. Br. J. Manag. 2000, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Stuart, H.W., Jr. Value-based business strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 1996, 5, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyal, L.; Gough, I. A Theory of Human Need; Macmillan: Houndmills, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M. Development and human needs. In Real Life Economics: Understanding Wealth Creation; Ekins, P., Max-Neef, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1992; pp. 97–213. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C.; Glover, J. Women, Culture, and Development: A Study of Human Capabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fearne, A.; Garcia Martinez, M.; Dent, B. Dimensions of sustainable value chains: Implications for value chain analysis. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, C.; Jenkins, B. Tackling Barriers to Scale: From Inclusive Business Models to Inclusive Business Ecosystems. 2011. Available online: https://www.hks.harvard.edu (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine. 13 September 1970. Available online: http://www.colorado.edu/studentgroups/libertarians/issues/friedman-soc-resp-business.html (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Melo, T.; Garrido-Morgado, A. Corporate reputation: A combination of social responsibility and industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Swaen, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, M.; Qian, C. Effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance: A competitive-action perspective. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A.; Vlachos, P.A. I think they think we are good citizens: Meta-perceptions as antecedents of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Chatterjee, P.; Demir, K.D.; Turut, O. When and how is corporate social responsibility profitable? J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M.; Nagati, H.; Chtioui, T.; Rebolledo, C. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and market value: Family versus nonfamily firms. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S. “I need you too!” Corporate identity attractiveness for consumers and the role of social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 71, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, R. The path of Kyosei. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R. Project-based competition and policy implications for sustainable developments in building and construction sectors. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15423–15448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiuma, G.; Carlucci, D.; Sole, F. Applying a systems thinking framework to assess knowledge assets dynamics for business performance improvement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8044–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R. Strategic product innovations and dynamic pricing models in oligopolistic market. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2017, 76, 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. System dynamics modeling: Tools for learning in a complex world. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R.; Chien, K.M.; Hong, L.Y.; Yang, T.N. Evaluating the collaborative ecosystem for the innovation-driven economy: A systems analysis and case study of science parks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, S. The Statistics of Word Co-Occurrences: Word Pairs and Collocations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E. Strategic collaboration between nonprofits and businesses. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2000, 29, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, G. The Long Interview; Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. L’analyse de Contenu, 9th ed.; PUF: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introductory to Theory and Methods, 5th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K.D. Grounded Theory in Management Research; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, L.B. Asking questions of the data: Memo writing in the grounded theory tradition. In The Sage handbook of grounded theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publishing: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, A.; Atkinson, P. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Jeong, E.; Park, K.; Yang, J.; Park, J. The relationship between technology, business model, and market in autonomous car and intelligent robot industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 103, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the mechanism of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation prone and innovation averse societies: Economic performance in Europe. Growth Chang. 1999, 30, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. Networks of innovators: A synthesis of research issues. Res. Policy 1991, 20, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.; Leibold, M.; Voelpel, S. Strategic Management in the Innovation Economy; Publicis and Wiley: Erlangen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Greening, D.W. The effects of corporate governance and institutional ownership types on corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 564–576. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Law, R. You do well and I do well? The behavioral consequences of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, K.B.; Agle, B.R.; Phillips, J.C.; Ingerson, M. The impact of moral stress compared to other stressors on employee fatigue, job satisfaction, and turnover: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Vanhamme, J. Theoretical lenses for understanding the CSR–consumer paradox. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. What is innovation and entrepreneurship? Lessons for large organizations. Ind. Commer. Train. 2001, 33, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R. Improving entrepreneurial knowledge and business innovations by simulation-based strategic decision support system. Knowledge Manag. Res. & Practice. 2018, 16, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F. Managing innovation and quality of collaborative R&D. In Proceedings of the 5th International & 8th National Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12–14 February 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, R.D.; Webb, J.W. Crossing the great divide of strategic entrepreneurship: Transitioning between exploration and exploitation. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamaki, M.; Rabetin, R.; Möller, K. Alliance capabilities: A review and future research directions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 68, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Kapoor, R. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Rong, K.; Xue, L.; Luo, L. Evolution of collaborative innovation network in China’s wind turbine manufacturing industry. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2014, 65, 262–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X. Growth of a platform business model as an entrepreneurial ecosystem and its effects on reginal development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, J.P.; Holburn, G.L.F.; Vanden Bergh, R.G. Nonmarket strategy performance: Evidence from US electric utilities. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1209–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.S.; Phillips, F.; Park, S.; Lee, E. Innovation ecosystems: A critical examination. Technovation 2016, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B. Business and communities—Redefining boundaries. NHRD Netw. J. 2012, 5, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojamo, S.; Larson, E.A. Investigating food and agribusiness corporations as global water security, management and governance agents: The case of Nestlé, Bunge and Cargill. Water Altern. 2012, 5, 619–635. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzeck, H.; Boechat, C.; Leao, S.F. Sustainability as a driver for innovation: Towards a model of corporate social entrepreneurship at Odebrecht in Brazil. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzeck, H.; Chapman, S. Creating shared value as a differentiation strategy—The example of BASF in Brazil. Corp. Gov. 2012, 12, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigin, I.; Rutherford, R. Shared value and the impartial spectator test. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CSV (creating shared value) | CSR (corporate social responsibility) | |

|---|---|---|

| Business philosophy | Core of business operation | Periphery of business operation |

| Driven force | Internally | Externally |

| Focus on | Balance between economic and social benefits | Economic-social perspective: pursue corporate social performance (CSP) or corporate financial performance (CFP) Stakeholder perspective: Meet stakeholders’ expectations |

| Competitive strategy | Social concerns integrated into business models | Corporate performances are an additional benefit, and not relevant to competitive strategies |

| Joined | Name | Work Corporation | Position | years of experience | # Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brander | Amy | Macy’s Merchandising Group (MMG) | Ex-general manager | 20 | 2 |

| Becky | Sales | 8 | 1 | ||

| Candice | Sales | 15 | 1 | ||

| Debby | Sales | 20 | 1 | ||

| Supplier | Randy | Tainan Enterprises Co., Ltd. | CSR Manager | 6 | 2 |

| Ellen | CSR Employee | 2 | 1 | ||

| Fanny | Sales Manager | 10 | 1 | ||

| Gina | Sales Manager | 18 | 1 | ||

| Consumers | * Beddy | Polo Ralph Lauren | Director of Technical Design | 1 | 1 |

| * Cindy | Pro-Hot Enterprise Co., Ltd. | Business Development Manager | 9 | 1 | |

| Georgia | Retired | --- | --- | 1 | |

| Nancy | Retired | --- | --- | 1 |

| Data collection | Joined | Number | Time/Location of Interview | Hours * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal interview | Consumers | 4 | 2019 March/Coffee shop in Taiwan | 30 |

| Employees | 4 | 2019 September/MMG meeting room | 15 | |

| Suppliers | 4 | 10 | ||

| Secondary data | Books, journal articles, web page information, news, and conference records | 20 | ||

| Total | 65 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, T.-K.; Yan, M.-R. The Corporate Shared Value for Sustainable Development: An Ecosystem Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062348

Yang T-K, Yan M-R. The Corporate Shared Value for Sustainable Development: An Ecosystem Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062348

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ta-Kai, and Min-Ren Yan. 2020. "The Corporate Shared Value for Sustainable Development: An Ecosystem Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062348

APA StyleYang, T.-K., & Yan, M.-R. (2020). The Corporate Shared Value for Sustainable Development: An Ecosystem Perspective. Sustainability, 12(6), 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062348