Abstract

Human resources are the major input in health systems. Therefore, their equitable distribution remains critical in making progress towards the goal of sustainable development. The purpose of this study is to evaluate equity in the distribution of healthcare human resources across regions of Poland from 2010 to 2017. This research by applying specifically to Polish conditions will allow the existing gap in the literature to be closed. Data were derived from the Database of Statistics Poland, and the Lorenz Curve/Gini coefficient was engaged as well as the Theil index to measure the extent and drivers of inequality in the distribution of healthcare human resources in macro-regions. Population size along with crude death rates are employed as proxies for healthcare need/demand. This research has several major findings. Mainly, it was found, that the geographical distribution of all types of human resources is less equitable than is the case with population distribution. Relatively lower equity in the access to oncologists, family doctors, and cardiologists was found. There are some noticeable differences between macro-regions in the equity level of healthcare human resources distribution. This research provides various implications for policy and practice and will allow for improved planning and more efficient use of these resources.

Keywords:

health care; human resources; inequality; Gini coefficient; Theil index; JEL classification: I11; I14; I15 1. Introduction

This article analyses the equity of distribution of healthcare human resources in Poland in the context of sustainability. This is a relevant area of research, given that healthcare human workforces are lacking globally, with an international market for their skills [1], and it is a phenomenon that influences sustainable development. Sustainable development is a model for an economy, which is based on increased environmental and social responsibility [2]. Interaction between these three pillars, namely the economy, society, and environment, is a major determinant for achieving a healthy and sustainable society [3]. So, health is an outcome of sustainable development, but simultaneously, it is also a precondition for sustainable development [4].

This study focuses on healthcare human resources due to several reasons: the health sector is more labour-intensive compared to other sectors and the workforce in this sector is an even more important component for the sector’s performance and consequently for the health of the population [5,6]. Thus, inequity in the access to healthcare human resources might decrease the access to healthcare services but also deteriorate their quality, thereby reducing health benefits. The geographical aspect of healthcare human resources distribution is relevant to sustainability issues because equitable access to a physician has an impact on equitable access to healthcare services, which then have economic and social consequences for the well-being of present and future generations. Because of this, sustainable development requires actions that will strengthen the equity in healthcare human resources distribution [7]. Additionally, healthcare human resources consume a significant portion of the financial resources available to the health sector.

For the above reasons, the description, analysis and understanding of the phenomena of inequity in the distribution of healthcare human resources are of vital importance in order to ensure the sustainability of the welfare state as a whole. Accordingly, monitoring changes in the disparities of healthcare human resources is essential for identifying gaps and will allow for a better understanding of which groups/areas are being left behind and facilitate the implementation of effective and appropriate interventions. The objective of the present research is to continue research by extension to Poland and to contribute with data and results in the field in the distribution of healthcare human resources. Poland is a country, that experiences inadequate numbers of doctors. To the best knowledge of the author, this is the first research on equity in the distribution of healthcare human resources in Poland of such a broad range and in the context of sustainability.

This research is framed within the prevailing international scientific literature, documents and previous studies on equity in the distribution of healthcare human resources, and the perspective of sustainability. The research problem analysed in this article is whether distribution of healthcare human resources across the main types of healthcare workforce in the period from 2010 to 2017 ensures sustainability. For this purpose, the Gini coefficient is used to identify inequities and the Theil index is used to identify drivers of inequality in the distribution of healthcare human resources at the macro-regional level. The engagement of a Lorenz Curve with the data on the population size and crude death rates allowed a comparison of the demand-supply differences between regions.

The starting hypothesis is that the distribution of healthcare human resources is characterized by inequities and variation according to their types. If human resources in Poland are at higher risk of inequitable distribution, then they should be a key element of a policy aimed at strengthening their distribution to be more equitable. The results discussed below support the hypothesis that there is relatively lower equity in the access to oncologists, family doctors, and cardiologists in both population and geographical distribution, while the most common causes of death are cardiovascular diseases and cancer. Also, together they are responsible for more than half of the disease burden [8].

The results presented by this article are important to continue the advancement of knowledge on the subject of equity in healthcare human resources distribution and its impact on sustainability. The analysis is particularly relevant for decision-makers at the national and European Union levels, since any inequity in healthcare human resources distribution poses major challenges.

This article is organized as follows. After the introduction (Section 1), the theoretical background with a literature review is presented in Section 2. Next, Section 3 is devoted to a description of the Polish health care system and, in Section 4, the methodology with data has been presented. In Section 5, the results are presented, and a debate is described based on the empirical contrasts, followed by discussion in Section 6. Finally, the conclusion is presented in Section 7.

2. Theory Background and Literature Review

Sustainability is also defined as the goal of a process called ’sustainable development’ [9]. According to the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development [10] sustainable development is a model, which comprises three principal aspects, such as economic, environmental, and social development. These elements are interrelated and complementary allowing for wellbeing for the present and future generations. Thus, sustainable development implies such types of both economic and social development, which ensures the protection and enhancement of the natural environment as well as social equity and human well-being for the present and future generations [11,12]. According to the Kickbusch model (2010) [3], the interaction between the three pillars of sustainable development (it means: economy, society, and the environment) is a main determinant for achieving healthy and sustainable society.

It implies, that health is an outcome of sustainable development but simultaneously it is also a precondition of sustainable development [4]. As the World Health Organization defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [13]. Thus, health is a state of being as well as a kind of ‘resource for living’ because it allows people to function and participate in many activities of the society [14]. Therefore, health is highly valued and prioritized within society. Good health contributes to development, economic growth, and the overall well-being of society not only directly, but also indirectly through income and wealth [15]. The indirect impact of health can be noticed by the influence of health improvement on the increase in the return on other elements of human capital such as education and professional experience [16]. Healthy children are better able to learn, and being healthy influences their ability to work or pursue an education and in general a range of opportunities and life plans [15]. So, the equivalence between the idea of health and the idea of sustainable development is transitory [17].

Therefore, health goals command a significant position on the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This Agenda was adopted by many countries in 2015 with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals and on 1 January 2016, officially came into force [18]. All these goals should be achieved by 2030 [19]. The third goal of the Agenda, which is related to health, calls for ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all ages in order to achieve sustainable development [18]. This progress in helping to save the lives of millions can be achieved by providing more efficient funding of healthcare systems, increasing access to physicians, improving sanitation and hygiene, and a reduction of ambient pollution.

In addition, target 8 of third goal (3.8.) of the above agenda calls for universal health coverage, which goal is to provide all people with all the health services they need [18,20]. These services should be saved, sufficient quality and provided in the effective way without exposing to financial hardship in paying for the services [21]. By ensuring such widespread coverage, not only will individuals benefit, but also all of society, as the population health can be improved [17]. So, expansions in health system coverage would lead, on average, to better health of the population [22]. Both the World Health Organization [15] and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [23] provided evidence that some countries have improved health indicators and contributed to stronger economic development as well as reduced the poverty levels by increasing coverage with health services. That’s why the introduction of universal health coverage has become a major goal of health care system reform in many countries as well as a priority objective of the World Health Organization [15]. Therefore, it has been become the core health goal of the Sustainable Development Goals, which “links equitable social and economic development, and combines financial risk protection with equitable access to essential services” [20].

The importance of equitable access is also underlined in the goal 10 of the above agenda. It shows that equity is the base of the sustainable development goals [18]. The importance of equity implies from the fact that it applies to fair opportunity for everyone to achieve their full health potential regardless of demographic, social, geographic or economic status. It implies the minimization of differences in access, coverage, quality, use and utility of healthcare services between groups of the population classified by above characteristics [24,25]. As inequalities in access to health services may lead to a low level of health [26]. Meanwile. adequate access to the highest attainable health standard for everyone has been recognized also as a fundamental human right and a key element in reversing socio- economic and healthcare system inequities [27].

All these health-related goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development call for equitable access to health services, as it is important for the sustainable development. Also, the World Health Organization points out that sustainability development requires an efficient health system that provides the entire population with equitable access to good quality services, health workers, technologies, and medicines [21].

One of the main features of the health sector and especially of healthcare is that it is more labour-intensive compared to other sectors, and thus the healthcare staff is an even more important component for its performance [5,6]. Therefore, European Commission underlined in its documents that “the capacity of health systems to deliver health services and meet the changing demands of care strongly depends on the availability of a workforce with the right skills and flexibility” [28].

The healthcare workforce is also referred as healthcare human resources and defined as the different types of both clinical and non-clinical staff who “make each individual and public health intervention happen” [5]. As health care system requires qualified staff to function well [27], thus the World Health Organization underlines the importance of investments in human capital.

Investment in human capital is one of the four functions of a healthcare system. According to the World Health Organization, there are several universal functions that each healthcare system performs and which influence the achievement of the fundamental goals within different healthcare systems. In every widely differing health system around the world, these functions are readily identifiable with the most familiar function being the service provision, followed by the financing function (the process of collecting revenues and allocating them in the systems), and then the third, stewardship (the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care). The fourth and final function is investment in creating resources such as human and physical [29]. Based on Becker [30] human resources can be treated conceptually, in the same way as physical capital. Thus, education and training are the key investment tools that are used to adjust the stock of human resources and also their available knowledge and skills. The health-care system must also balance investments in human capital to meet future needs and present demands [29].

The responsibility of healthcare system decision-makers is to invest wisely, because in the short term, the health system can only use the available human resources, which were created in the past, whereas investments are long-term, therefore they must be precisely made by the system because it is difficult to change anything in the short-term, even how they are employed. Nowadays, in order to achieve sustainability as a strategic goal, healthcare systems are facing significant challenges as they must cope with the increasing demands of citizens for healthcare but with decreasing resources [31]. A stronger focus on education and training to leverage the skills and enhance the productivity of healthcare human resources will directly support healthcare sustainability. Thus, healthcare systems can proceed towards sustainability by strengthening investment in human resources [31,32,33].

Therefore, such investment decisions should take into account all the elements, which influence the level of the healthcare workforce. The European Commission indicated such determinants of a healthcare workforce, divided into external and internal, where external determinants are population aging, changing healthcare demands, migration patterns, technological innovation, and internal determinants are workforce aging, recruitment and retention, geographic distribution, and skills mismatches [28]. Better geographical distribution of the healthcare workforce would allow achieving more efficient use of available numbers [29].

So, the healthcare workforce is central to the healthcare system’s performance and thus to overall population health as the available quantity and quality of healthcare services depends to a large extent on the size, skills, knowledge, geographical distribution, and attitudes of the workforce and the right balance between the different types of health care-givers [34,35]. Therefore, based on the literature review, the assumption is made in this paper that a better geographical distribution of healthcare human resources is crucial from the sustainable development perspective.

This geographical distribution matters a lot in the context of healthcare human resources since it determines the availability of healthcare services―their types, quantity and quality. Any imbalances could raise problems of equity, meaning that services will not be available according to needs, then efficiency and effectiveness of services, and finally the satisfaction of users. Although a perfect balance is probably utopian, it is however conceivable to build strategies that are based on a good understanding of the dynamics to achieve a better distribution [36].

Yet many European countries are faced not only with healthcare workforce shortages but also with geographical maldistribution of healthcare professionals [1,37,38,39,40,41]. The shortage of healthcare workers is compounded by the phenomena that their skills and competencies are often not optimally suited from the perspective of changing population health needs [42,43].

The problem of inequities in the distribution of healthcare human resources seems to be a worldwide problem and in fact there is a growing literature that aims at understanding equity in the distribution of different groups of healthcare workforce and also in a wide range of countries. They provide the evidences of inequity existence in the different groups of healthcare human resources. For example, in Sweden, the degree of inequality in the geographical distribution of general practitioners was identified [44]. Also, some level of inequity was found in Greece and Albania in the case of primary care physicians [45] and in Albania in the case of general practitioners [46]. Then, inequities were found in such distance country as Australia, where despite there being more general practitioners per capita, their distribution became increasingly unequal and inequitable in analysed period (as rural and remote divisions became increasingly poorly served) [47]. Then, Matsumoto et al. (2010) compared the situation of physicians in Japan and US, by examination of the associations of physician employment status with the number and geographical distribution of the physicians in each specialty. They found that the Gini coefficients values were substantially higher for Japanese specialists than for the US, which means higher inequities [48]. In England and Wales, inequities were also found. The research confirmed that conducted policies did not lead to a reduction in inequality to access to general practitioners in England and Wales [49]. The problem of district inequities to access to healthcare human resources has been also identified in India [50]. Then, Erdenee et al. (2017) found that, in Mongolia, the distribution of healthcare human resources was adequate for the population size although a striking difference was found in case of the geographical distribution. However, they also concluded that, when formulating policy, it is necessary to take into account such features, in Mongolia, for example, as the nomadic lifestyle of rural and also remote populations. Therefore, it is important to consider such geographical imbalances, rather than simply increasing the number of healthcare resources [51]. Then also, inequities were found in distribution of different types of healthcare human resources in all Iran by Rabbanikhah et al [52] and Mobaraki et al [53] as well as in same only Teheran by Sefiddashti et al [54]. In the Indonesian healthcare sector, some improvement of equity in the distribution of doctors was identified by Paramita et al [55]. There is a bunch of research in the context of China healthcare sector. Even the increase of different types of healthcare human resources took place with different levels of inequity in the distribution of them found in China by Li et al [56], Wu et al [57] Lu and Zeng [58], Zhang et al [59], and Jin et al [60]. Also in Japan, Kobayashi and Takaki [61] did not found any improvement in the equality in physician distribution as well as Toyabe [62]. Then, Munga and Maestad [63] found significant inequalities in the distribution of health workers in Tanzania. Wiseman et al [64] conducted research in Fiji and found greater inequalities in the density of health workers at the provincial level compared to divisional level. Also, inequities in the distribution of healthcare workers were found in Cameroon by Tandi et al [65].

These studies show that many different countries suffer from the inequities in distribution of healthcare human resources [51]. Also, these studies indicated that country-specific lifestyle and culture should be taken into account when analysing equity in the distribution and formulation of healthcare human resources strategies.

Empirical literature on the equity in the distribution is also eclectic in terms of the methodological approach. Generally, the research conducted on the equity in the distribution are based on either traditional economic methods such as Gini coefficient, concentration index, Theil index or Robin Hood index, presented in Table 1 [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65], or some econometric and spatial techniques, or a mixed approach [66]. The involved method is determined by the purpose of research but also by the range of available data. Therefore, the scope of this study is in the current range of empirical studies, which are presented in Table 1. Another range of studies in the area of equity in the distribution and in distribution of healthcare human resources focuses on identification of physician distribution determinants [67] or predictors of the physician to population ratio [68], or examination of relationships between the inpatient flow ratio and selected variables as physician density, the elderly ratio, and hospital bed density [69] or physical and social environmental variables [70]. These studies are also based on econometric models and mixed approaches.

Table 1.

Selected literatures on the equity in the distribution of different types of healthcare human resources.

Due to the above, the problem of shortage and inequities of healthcare human resources distribution is an international problem, the World Health Organization as well as the European Commission-which are key international stakeholders, have undertaken many important initiatives, responding to the challenges of the healthcare human resources crisis [71,72,73]. In 2004, the World Health Organization clearly stated in its report that even though healthcare workforce is an essential component of healthcare systems development, there is a lack of recent consistent research on this subject. Also, it stressed the need to elevate healthcare human resources position in the international political agenda [74]. In 2006, WHO published the Human Resources for Health in the WHO European Region Report [75]. It was the first report in which many of the core issues facing healthcare human resources across Europe have been addressed comprehensively. In 2006, The Global Health Workforce Alliance was prepared as a common platform for action to address the crisis of healthcare human resources [76]. Also, an important initiative of the European Commission was the development of the European Commission Green Paper on the European Workforce for Health, which was a response to the challenges of the healthcare human resources crisis [77]. The next important initiative was the development of the WHO Global Atlas of the Health Workforce [78]. This electronic platform makes it possible to collect statistical data on medical staff according to geographical distribution but also age and gender. A comparatively important WHO initiative was the development of the Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel [79]. Then, such an EU initiative, namely the Joint Action on Health Workforce Planning and Forecasting, was set up in order to support country efforts in healthcare workforce development [80]. Also, the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 [81] was published in order to increase awareness about the health workforce importance, also when it comes to new challenges in the healthcare system [82]. The World Health Organization noted in its documents that the health workforce will be crucial to achieve health and wider development-related objectives in the next decades [81].

Therefore, the main goal of the policies applicable in European countries and other countries is to achieve and sustain a skilled healthcare workforce at the level which would allow to cope with increasingly complex healthcare needs [37,77,80,83]. Especially, these shortages are likely to get worse as demographic trends, combined with terms of employment for many health sector employees, lead to a wave of retirements, just as demand for health services is increasing [40]. Thus, health workforce planning has been attracting academics’ attention for more than three decades [84,85]. Among others, Dubois et al. (2006) offered a synthetic picture of the physician labour market in the EU [86]. Then, Malgieri et al. (2015) and Ono et al. (2013) provided the most comprehensive and methodologically advanced sources of information regarding the current state of physician manpower planning [87,88]. Unfortunately, Poland is absent from these two key volumes despite the fact that the state of doctors in Polish healthcare system is the most difficult one of all EU countries [34]. Therefore, as a research subject, Poland was chosen.

According to the above statement, the aim of this research is to assess the geographical distribution of healthcare human resources and compare it with population distribution according to different types of them in Poland. It will allow to identify the group of healthcare human resources which are at higher risk of inequities regarding their access. Therefore, it could be the basis for improvement of the health policy. Moreover, the equitable distribution of human resources in healthcare remain critical in making progress towards the goal of universal health coverage and also with regard to sustainable development (the Sustainable Development Goals 2016–2030 [89]). Furthermore, due to that, sustainable development requires actions which would strengthen poor geographical distribution. There are no such structured studies in this context for Poland as there are only some studies conducted from different context and perspectives [90,91,92,93]. Thus, this research will allow to fill in the gap in existing literature.

3. The Characteristics of Polish Health Care System

The Republic of Poland is a country with the location in central and eastern Europe with the Human Development Index of 0.865. Poland is also largest country among the new Member States admitted to the EU after 2004 with the population of 38.1 million and area of 312,685 km2 in 2018 [94].

However, Poland is characterized by the lowest ratio of practicing physicians per 1000 population among the EU countries. In 2016, the number was 2.4 in Poland, while it was 3.6 in the EU on average. Moreover, this is accompanied by a significant migration rate of physicians to other EU countries (above 7%). Also, the average age of medical doctors in Poland was 50.2 in 2017 (and 54.2 for specialists) [8]. More worrying is that in Poland, over 26% of physicians are over 60 and only about 22% are younger than 35 [95]. All of these factors cause that, the situation for Polish physicians is among the most difficult of all EU countries. Along with other consequences, this results mainly in waiting lists and unmet health needs [34]. Moreover, even life expectancy at birth has been increasing, with the EU average of 81 years being higher than the average of 78 years in Poland. The most common causes of death are cardiovascular diseases and cancer, which also, together, account for over half of the disease burden. OECD data shows that about 9% of all Polish physicians work as general practitioners. This is low compared with the average of 23% of all physicians among 23 EU countries [8], mainly due to the problem that family medicine is not a popular specialization in Poland [96]. Therefore, internal medicine specialists and pediatricians are allowed to work as family medicine physicians [95]. Currently, the development of family medicine and primary care is the core subject of healthcare reforms in Poland. Due to this shortage of physicians in Poland, access to healthcare services is also a cause for serious concern. In addition, the dominance of specialists among doctors has been noted in Poland. Specialists account for 85% of all physicians as compared to an average of 62% for the 29 OECD countries. However, the shortage of doctors in some specialties is becoming one of the most important reasons for limited access to healthcare and lengthening of the average waiting time [34]. In addition to this, in 2016, the number of practicing nurses per 1000 population was 5.2, which was significantly lower than the 8.4 average for the EU [97], while both health and equity remain important values in the Polish system.

Article 68 of the 1997 Constitution of the Republic of Poland ensures the right to equal access for all citizens, regardless of their financial status. However, all detailed conditions for, and the scope of the provision of services are established by statute [98].

The Polish perspective on actions regarding sustainable and responsible economic development has been formulated in the Strategy for Responsible Development (SRD). The new development model for Poland set out in the Strategy meets the expectations formulated in the 2030 Agenda.

Historically, the main source of healthcare financing in Poland was the government’s budget. However, the radical change took place in 1999, after ten years of market economy implementation [99]. In January 1999, the 1997 General Health Insurance Act was introduced, which meant the beginning of a general obligatory health insurance system [100]. It changed the way of healthcare financing from budgeting into insurance-budgeting system. These changes were followed by the separation of the purchaser function from provider function. So, the decentralization of the system took place [101]. As the purchaser function started to be performed by newly created health insurance institutions, the so-called sickness funds (kasy chorych). Sixteen sickness funds were founded―one for each voivodeship―and a separate sickness fund for the uniformed services (members of the military, the police, and the state rail) [102]. Soon, this system was criticized by the new left-side government due to the considerable differentiation of the number and quality of healthcare services in each individual region, as it potentially infringes on the “equity” rule prescribed in the Constitution. Finally, instead of improving this system, the new government implemented a different solution by enforcing a law on general insurance in the National Health Fund on April 1, 2003 [103].

Thus, a single central insurance institution (named the National Health Fund) replaced sickness funds and the Head Office of the NFH with 16 regional branches (it means one in each voivodeship) was established. This meant the centralization of the public funds for healthcare. Also, the law introduced uniform contracting procedures as well as points limit for contracted services in order to eliminate regional differences in the access to healthcare [104]. However, shortly after, in January 2004, the law on universal insurance in the National Health Fund was found as not standing in accordance with the Constitution. Therefore, the law on health benefits financed from public means was passed by the Sejm of the Republic of Poland at the end of July in 2004 [105], but the general idea of insurance and insurance institution of National Health Fund remained [106].

In the Polish healthcare system, the functions of management, stewardship and financing are divided between the Ministry of Health, the National Health Funds (NHF) and territorial self-governments. Mainly, the Ministry of Health is responsible for governance of the healthcare sector and its organization. The Ministry is also responsible for national health policy, implementation and coordination of health policy programs, major capital investments and also for medical research and education. The Ministry also has a number of supervisory functions [103,104].

The major duty of the NHF is healthcare services financing, but it also manages the contracting process of healthcare services with public and non-public service providers (which means setting their value, volume and structure). The NHF is responsible for monitoring the fulfilment of contractual terms and also being in charge of contract accounting. This implies that NHFs are able to influence the quality and accessibility of healthcare services by negotiated terms [103]. As Poland has three levels of territorial self-government, at each administrative level, thus the responsibility of territorial health authorities is to identify the health needs of their respective populations. This information is needed for the purpose of preparing the plan of health services delivery, health promotion, and to conduct the management of public health care institutions [104].

Regarding to medical professions, it is the Minister of Health, who is mainly responsible for their regulation. The Minister of Health is supported by the respective professional chambers, national and voivodeship consultants, the voivodes as well as other institutions of the health section of the central government administration. Mainly by National Health Funds, which provide information about numbers of services which can be contracted and the Health Technology Assessment Agency with expert opinions in various areas of medicine, pharmacy and health sciences. So, the Minister of Health and the voivodes, with the support from national and voivodeship consultants, are responsible for preparing the plan of medical training. The Minister of Health is responsible for defining the number of medical training places (for physicians and dentists) then the number of medical specializations while the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) stipulates the academic standards and medical education procedures in medical universities. This plan is prepared based on the population’s health needs assessment and training capacities. Then, the National Chamber of Physicians (NCP) together with other professional associations are involved in postgraduate physician training [8].

4. Methodology

Data related to healthcare workforce used in this study was derived from the Knowledge Database Health and Healthcare of Statistic Poland for the period from year 2010 to year 2017 [107]. As Poland is divided into 16 voivodeships (regions), thus this study used, voivodeship-level data on healthcare workforce and each voivodeship was considered as a unit of analysis (voivodeships: Lower Silesian, Kuyavian-Pomeranianranian, Lubelskie, Lubuskie, Łódź, Lesser Poland, Masovian, Opole, Podkarpackie, Podlaskie, Pomeranian, Silesian, Świętokrzyskie, WarmianMasurian, Wielkopolska, and Zachodniopomorskie). According to, Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), all voivodeships are grouped into 6 macro-regions (in the period from 2010–2017). Thus, a level of inequality was also calculated for six macro-regions such as: central, northwestern, southwestern, northern, southern and eastern. This allows to analyze between macro-regions inequity as well as across macro-regions inequity.

The study data consisted of the number of physicians, number of nurses, number of dentists and number of pharmacists and number of all types of specialists. Moreover, data regarding the number of 16 different types specialists (which are more than 85% of specialist in general) were also collected. In order to analyze the density of resources, these numbers were then converted and expressed as number per 10,000 people and per square meter. Population and geographic area data were obtained from the Polish Statistical Yearbook 2010–2017 [94]. Number of them were used as the indicators of health care resources in each region.

In order to examine the distribution of healthcare resources against population size and geographic size in Poland, the Gini coefficient calculated based on the Lorenz Curve was engaged, because it is recognized as one of the most common measure of distribution and also as one of the superior tools for measuring inequity [44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,108,109]. The Gini coefficient was developed by the Italian Statistician Corrado Gini [110] as a summary measure of income inequality in society [111]. In this study, the Gini coefficient was calculated based on the Lorenz curve as a graphical representation [59,60]. The Gini coefficient is defined as the ratio where the numerator is the area between the Lorenz curve of the distribution and the uniform distribution line while the denominator is the area under the uniform distribution line. Thus, the actual extent of inequality is presented by the area between Lorenz Curve and the line of perfect equality. It means, that more even distribution would be recognized in case of less deviation from the line of perfect equality.

The ratio can vary from 0 to 1, where 0 corresponds to perfect human resources distribution (i.e., every units has the same resources per 1 square km.) and 1 means perfect human resources inequality (i.e., one has all the human resources, while everyone else has zero resources). Then Gini coefficient with the value less than 0.3 shows preferred equity status, while between 0.3 and 0.4 means normal condition, while Gini coefficient with the value between 0.4 and 0.6 triggers an alert of inequity, and the value exceeding 0.6 represents a highly inequitable state.

Two indicators were used for measuring inequity, reflecting the distribution of healthcare human resources among populations and the second among geographical location. The following formula was used:

where yi denotes the value of i-observation and n the number of observations

The Gini coefficient allows for direct comparison between voivodeships with the different population and geographical sizes. Then, in order to find out drivers of inequity the Theil index was employed. The Theil index is also a measure of inequity, which allows sub-groups to be broken down within the context of larger groups [112].

Thus, the Theil index was employed to measure the overall equity in distribution of healthcare human resources in Poland but also mainly the contributions from each macro-region. The value of the Theil index ranges from 0 to 1 and 0 represents perfect equality, while 1 means completely unequal. The Theil index is calculated as follows:

where Pi denotes proportion of population in one region / macro-region accounting for the total population and Yi the proportion of healthcare human resources in one region/macro-region accounting for the total healthcare human resources

If the research areas are divided into several groups (e.g., k groups in the formula, central, northwestern, southwestern, northern, southern and eastern in this case), the Theil index can be decomposed into the Tintra−class and Tinter−class. Then, by dividing Theil index as the proportion of Tintra−class and Tinter−class, the contribution rates within and between groups can be calculated. The higher proportion of Tintra−class indicates that the inequity in healthcare human resources distribution results more from the within-macro-regional difference and vice versa. While the higher proportion of Tinter−class, indicates that the inequity in healthcare human resources distribution results more from the intern-macro-regional difference between central, northwestern, southwestern, northern, southern and eastern Poland, and vice versa.

Tintra−class: degree of equity in healthcare human resources distribution within the macro-regions.

Tinter−class: degree of equity in healthcare human resources distribution between the macro-regions.

Tg: Theil index of healthcare human resources distribution in macro-region.

Pg: proportion of population in one macro-region accounting for the total population.

Yg: proportion of healthcare human resources in one macro-region accounting for the total healthcare human resources [113].

The Theil index allows to decompose the overall inequality into “within group inequality’ and ‘between group inequality’. The first element results solely from variation in healthcare staff density inside the groups (macro-regions) and the second element results solely from the variations in healthcare staff density across groups [112,114]

Finally, a measure of ‘need’/demand was also introduced to explore further issues of healthcare human resources inequalities. Based on the literature review, it was recognized that some analysts have started to use some alternative measures of need/demand, which allow them to overcome the problem of limitation of routinely available data. Such ratios as infant mortality ratios, standardized mortality ratios, as well as crude all-death rates are used as a proxy for healthcare needs/demand [47,64,65,115]. Following this approach [46,64], the population size with crude death rates are employed as proxies for healthcare need/demand. All computations were conducted in Excel.

5. Results

In this study, the assumption about importance of equity in the access to healthcare human resources for sustainability was made. The results confirmed that, even density of different groups of healthcare workforce expressed as number of them per 10,000 population increased from 2010 to 2017, however, the variation of these changes have been observed (Table 2). While the change of density of pharmacist and physicians were at the level of 16.92% and 14.08%, respectively, the density of nurses changed only by 5.22% from 2010 to 2017 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Density of the main groups of healthcare human resources (per 10,000 population) in Poland in the years from 2010 to 2017.

When the density of healthcare human resources expressed as a number per 1 square km was analyzed, this same pattern is observed. The highest change has been noted for pharmacist while the lowest change has been reported in the case of nurses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Density of the main groups of healthcare human resources (per 1 square km) in Poland in the years from 2010 to 2017.

Then, from the analysis of different types of healthcare specialist, it has been noted that 16 types of specialist, which represent more than 85% of total specialists in Poland, also showed variability in terms of the amount by which theses resources have been changed in 2017 compared to 2010 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Density of healthcare specialists (per 10,000 population) in Poland in the years from 2010 to 2017.

The number of all specialists per 10,000 people changed by 13.26%, however this change showed a variable tendency. The most significant changed can be observed in case of oncologists (115.51%) and cardiologists (67.44%). Moreover, the density of these specialists expressed as number of them per 10,000 population gradually increased from 2010 to 2017. However, in case of three out of sixteen specialties, such as internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and occupational medicine, the decrease of their amount per 10,000 population was noticed as for internist by 10%, obstetrics and gynecology by 4.13%, and occupational medicine by 1.06%.

Analysis of density expressed as a number of different types of specialists per 1 sq km presented also similar tendency. The most significant change has been observed in case of oncologists (117.01%) and cardiologists (by 68.60%) (Table 5). There was also decrease of number of such specialists per 1 square km: internist (by 9.37%), obstetrics and gynecology (3.46%), and occupational medicine (0.37%).

Table 5.

Density of healthcare specialists (per 1 square km) in Poland in the years from 2010 to 2017.

So, generally, the density of the main groups of human resources and the majority of different types of analyzed specialists increased in the above period as compared with the most significant increase of oncologists and cardiologists. However, in the case of three out of sixteen specialties, including internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and occupational medicine, a decrease of their amount was observed.

The main part of the research, which relates to the goal of the paper, consists of measuring the level of equity in the access to workforce in healthcare and finding the differences in the distribution of healthcare human resources against population and geographical. The Gini coefficient was used to estimate inequalities in the population and geographic distribution of healthcare human resources based on their density. The Gini ratios confirmed relatively good equality in the distribution of physician, dentist, nurses and pharmacist against population size with ratios ranging between 0.04 and 0.17 (Table 6). What is also positive is that a slight improvement in the level of equality to access to physician, dentist, and pharmacist is recognized. Meanwhile, in the case of nurses, the slight increase was noted in the analyzed period, which means a deterioration of equity in the access to them.

Table 6.

Gini coefficients of population distribution of the main groups of healthcare human resources in the years from 2010 to 2017.

The Gini coefficients against geographic distribution (Table 7) of above healthcare human resources range between 0.25 and 0.32 indicating relatively good and normal equality. However, the level of equity is worse comparing with the distribution of these workforces per 10,000 population. Also, a different pattern has been recognized as a slight improvement in the level of equality to access to nurse and pharmacist, while there is no change in the level of equity for the access to physicians. Also, the decrease in equity is noted in the case of dentists.

Table 7.

Gini coefficients of geographic distribution of the main groups of healthcare human resources in the years from 2010 to 2017.

In the case of total specialists and specialists in various fields of medicine, the Gini coefficients against population size ranged between 0.05 and 0.27, indicating relatively good equality (Table 8). However, there are five types of specialists for which an increase of the Gini coefficients was noticed, which means the decrease of equity to assess to them (cardiologist, internist, obstetrics and gynecology, otolaryngology, and surgeon).

Table 8.

Gini coefficients of population distribution of healthcare specialists in the years from 2010 to 2017.

In the case of healthcare specialists, the Gini coefficients against geographic distribution ranged between 0.25 and 0.43 (Table 9), which triggers an alert of inequity. Also, there are three types of specialists for which the increase of the Gini coefficients was noticed, which means the decrease of equity to access to them as for: anesthesiologist, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrician.

Table 9.

Gini coefficients of geographic distribution of healthcare specialists in the years from 2010 to 2017.

The results show that the geographical distribution of different types of specialists is less equitable then in case of population distribution. The Gini coefficients against geographical ranged between 0.25 and 0.43. For 11 types of specialist, the Gini coefficients were from the range above 0.30 (not only in 2017 but in most of the years of analysis) and three of them also had a value of this ratio above 0.4 during the analyzed period.

Then, the Theil index was employed in this research to calculate the global equity in healthcare human resources distribution for Poland and the contribution rate of six Polish macro-regions (central, northwestern, southwestern, northern, southern and eastern). The Theil index results shown in Table 10 (and expended version can be found in Tables S1 and S2) confirm a continuous improvement in the equity of healthcare human resources distribution in Poland. In terms of macro-regional divisions, the Theil index for the northwest shows relatively higher inequities then the remaining macro-regions for most healthcare human resources groups (apart from anesthesiologists, oncologists, neurologists, radiologists, pediatricians, and nurses). It was noted that central, southwest and eastern macro-regions suffer from relatively higher inequities in the case of oncologists. The southwest also suffers higher inequities in radiologist distribution in comparison with the rest of the macro-regions of Poland. Also, the northern part of Poland has relatively higher inequities in the distribution of nurses and pharmaceutics, while in the east of Poland, more inequities are apparent in anesthesiologists. In addition, Table 10 shows a decomposition of healthcare human resources inequalities. In the case of nurses, pharmaceutics, physicians, dentists and such specialists as psychiatrists, neurologists, pediatricians, oncologists, lung disease, cardiologists, and internists, overall inequalities in their distribution between macro-regions is much higher compared to overall inequality within the macro-regions. This means that, within macro-regions, these inequities are responsible for total inequities in the case of the rest of healthcare human resources groups.

Table 10.

Theil index of healthcare human resources distribution in the year 2017.

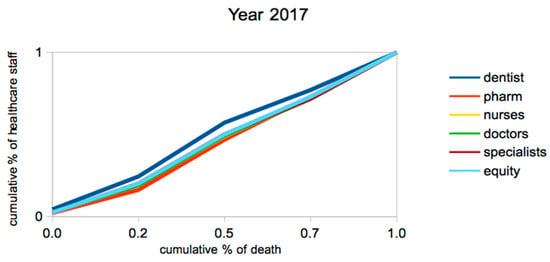

The Lorenz curve shows the cumulative share of healthcare human resources against the cumulative share of need (demand)/mortality when voivodeships/regions are ranked from those in lowest demand (meaning lower number of deaths) to highest demand. The diagonal line presents a perfectly equal distribution of healthcare staff (of those with lower of need for example 10% would receive only 10% of healthcare staff). The nearer the curve to the diagonal, the greater the degree of equality, while a curve further away from the diagonal means unequal distribution. Figure 1 shows that, at the regional level, the share of healthcare human resources increase is almost in proportion with need in the year 2017.

Figure 1.

Lorenz Curve presenting the healthcare human resources according to level of need.

At the regional (voivodeships) level (Figure 1), the Lorenz curve for all categories of healthcare human resources remains quite flat but there are some slight inequalities. Those who are better off (meaning with lower mortality) tend to have a slightly greater share of dentists than they would if the distribution were perfectly equitable. Moreover, the greater problem is that, for specialists (all specialists were analysed together), it seems to be just a few voivodeships which with the actual level of mortality receive a lower share of specialists and pharmaceutics than they would be expected to receive if things were totally equitable. This same tendency can be observed in the case of dentists and specialists in every year of the analysed period, and the opposite in the case of pharmaceutics (Figures S1–S7).

6. Discussion

This study has several major findings and merits. First, it has showed that geographical equity in the access to healthcare human resources matters from the sustainability perspective. Secondly, on the basis of the Gini coefficient, this paper reported some slight inequality of healthcare human resources distribution in Poland. The results showed that the geographical distribution of all types of healthcare human resources exhibited a slight level of inequality. Gini coefficient values for distribution by geographical area were in the range from 0.25–0.32 in the case of main groups of healthcare human resources and were in the range from 0.25 to 0.43 in the case of different types of specialists during all years of analysis. Meanwhile, in the case of population distribution, the values of Gini ratio were in the range 0.04–0.17 and 0.05–0.27, respectively. It showed that the Gini coefficients by geographical area were apparently higher than those by population, and they indicated inequality. It implied, that there was a larger disparity in the geographic distribution of health human resources than that in the population distribution. This could be the result of the sparsity of population, which would be consistent with the finding of Ucieklak-Jeż and Bem (2017) [116]. Probably, most of the Polish healthcare human resources are distributed within the developed provinces, and especially in large cities of developing provinces, fewer healthcare resources are allocated. The problem, however, requires further analysis, which should be expanded by including for example the analysis of the availability based on actual consumption of healthcare services provided by the above human resources.

Therefore, these results should be considered by health policy makers. Consequently, it is reasonable to suggest the Health Ministry (health policy maker) that it should take into account geographical distribution of healthcare human resources in the process of regional health planning in order to improve the equality in allocation of healthcare resources.

Thirdly, as the cardiology and oncology diseases are the main causes of Poles deaths and also, together they account for over half of the disease burden [8] then the increase of cardiologists and oncologists when expressed by 10,000 population and 1 sq. km. was a positive tendency. Further, the increase of oncologists was also accompanied by an improvement of equity in the access to them (for both population and geographical distribution). Meanwhile, more troubling is the deterioration of equity in the access to cardiologist as the increase of Gini coefficient against population was noted with no change in the case of geographical distribution. However, there was still relatively lower equity in access to both oncologists and cardiologists as compared with other specialists, which, in comparison with the above epidemiology tendency, may indicate that demand is not met

Moreover, the results of this paper confirm that Poland was also handling with the problem of family doctors and pediatricians. Generally, the amount of family doctors increased by 11.92% when it is expressed by 10,000 population and by 12.70% when it is expressed by 1 sq. km. However, the deterioration of equity in the distribution of family doctors against population has been noted and no changes in the level of equity in terms of geographical distribution. This same tendency has been noticed in case of pediatricians as the number of them increased by more than 10% and it was accompanied by a deterioration in their accessibility in terms of population distribution. As internists are allowed to work as general practitioners, then the decrease of their amount (also when expressed per 10,000 population and per 1 sq. km.), which was accompanied by a depreciation in equity of their population distribution, although an improvement was noted in terms of geographical distribution.

This problem of still relatively lower equality in the case of oncologists, cardiologists, family medicine, and internists implies that the health policy makers should strongly focus on the adaptation of the number and distribution of some medical specialists to epidemiological and demographic trends in the Polish healthcare system. Importantly, epidemiological trends show that cancer and cardiological diseases are the main causes of Poles death [8]. Thus, the government should pay more attention to this problem as the elimination of such differences in the access to these healthcare human resources can also improve the access to health benefits and reduce the length of average waiting time. It is also important to make this distribution sufficient enough in order to fulfill the universal accessibility of healthcare services and thus to lead to higher sustainability development.

Fourthly, the use of the Theil index generally confirmed the existence of some range of inequities in the distribution of healthcare human resources in Poland. Also, the results confirm the problem of still relatively lower equality in access to oncologists, cardiologists and family medicine specialists.

By using the Gini coefficient as well as the Theil index, it was possible to get a consistent picture that inequalities exist at the macro-region level in Poland. Both methods are noteworthy in their results. By using the Theil index, it was possible to separate out inequalities both between and within geographical divisions. These results showed some differentiation between geographical regions of Poland. In most types of healthcare human resources, relatively higher inequities can be found in the northwest macro-region. There are certainly macro-regional differences in the access to healthcare human resources.

Moreover, decomposition of the Theil index allowed to separate out inequalities between macro-regions and within macro-regions. Between macro-regions inequality is responsible for relatively more overall inequities in the case of doctors, nurses, pharmaceutics, dentists, and specialists in general and then such specialists as cardiologists, internists, lung diseases, neurologists, oncologist, psychiatrists, and pediatricians. In the case of the remaining analyses of healthcare human resources, inequality within the macro-region is relatively more responsible for overall inequalities, which implies that policy makers should think more carefully about the allocation of healthcare human resources at the macro-regional level.

Fifth, the overall distribution of physicians and nurses on the basis of need/demand was shown to be relatively equitable in Poland, while a slight inequity was found in the case of all specialists (analysed together), pharmacists and dentists. This implies, that generally healthcare staff tend to be allocated in areas where need is greatest and that the Polish healthcare system responds to healthcare demands as best it can with available healthcare human resources. It also implies that it would be good to extend the base of collected data by some alternative measures of need/demand which would correspond directly with the analyzed types of resources.

Sixthly, the level of access didn’t change significantly during the period of analysis which is troublesome. It implies that no or not enough corrective actions were undertaken by the health policy makers in this field, despite participating in some of WHO initiatives. For example the Ministry of Health has admitted its participation in the Joint Action on Health Workforce Planning, which the main purpose was the development of a sufficient number of healthcare human resources and the help in minimizing the gaps, which can be identified between the need for and supply of healthcare workforces equipped with the right skills [117].

The results show the need to correct the healthcare policy conducted by Ministry of Health as well as the contracting system conducted by National Health Fund in Poland. Thus, because of shortage of specialists, The Ministry of Health should retrieve the medical education policy as well as the aspect of medical professions regulations for which it is responsible. Thus, this research confirms that the Health Ministry should place the achievement and sustainment of a sufficient and skilled healthcare workforce on high on the policy agenda.

Then, the results confirm also the strong need for healthcare human resources planning in the area of health policy. Within the framework of healthcare human resources an important issue is health workforce planning [6], while the Polish Supreme Audit Office (2016) identified many obstacles in the case of the Polish healthcare system. It was noted that the Polish health policy suffered from the lack of a formal and long-term strategy regarding healthcare health resources planning, which in addition would be based on the epidemiological and demographic trends. Also, in Poland, the desired number of employees of individual groups of medical professions has not been determined, per population, which would be a basic condition for securing an adequate number of specialists [118].

Also, due to this inequity, policy regarding the healthcare workforce development in Poland is inadequate and insufficient, while according to WHO health workforce planning should be a major subject of a health policy [114]. Health policy makers should not only continually evaluate the distribution of human resources, but they should also prepare a plan for the allocation of human resources in the healthcare sector [54]. The policy makers in all levels, national, regional, and local, should pay attention as to how human resources are distributed sine equality is part of quality [48]. Thus, the results of this paper show also that there is also strong need to include the geographical distribution in the healthcare human resources planning. Therefore, this research supports the need of developing the proper planning of health workforce. Unlike solutions used in other countries, Poland suffers from the lack of dedicated departments or some governmental agencies which would be responsible for healthcare workforce development [34]. The problem is that Poland did not implement the data set, methodology, tools, and approaches which are recommended and commonly used in other countries in order to plan healthcare human resources and to project the future healthcare workforce [89,119].

Taking into account complexity of healthcare human resources, it implies that, holistic, systemic approach to healthcare workforce planning should be applied. Then healthcare policy makers should focus on the distribution of healthcare workforces towards a more equitable through more effective workforce planning. Also, the Ministry of Health should analyze the problem of disparity (spatial), which should be expanded by for example the analysis of actual consumption of healthcare services provided by the above human resources as well as making connection with health state to see what is its impact on health. In order to do this, the Ministry of Health should also extend the range of data collected as at the present moment it is not possible to identify exactly the consumption level of services in the classification that was used for the above analysis of healthcare human resources.

While healthcare workers are lacking globally, with an international market for their skills [1], these findings also suggest a need for more innovation in the policies in order to improve health equity in Poland, and also at the EU level.

However, there are several limitations with this study which should be underlined. Firstly, a weakness of this research is the inability to conduct powiat (counties) level analysis for all the various types of healthcare workforce, which is mainly because the data are disaggregated only down to the voivodeship level. County-level data is more accurate and, therefore, appropriate for providing concrete, in depth information and drawing out desirable health policy recommendations. Secondly, due to the lack of data, it was not possible to perform a separate analysis for rural and urban areas in order to control their impact on the analyzed human resources. Thirdly, the database did not detail the specific healthcare skills of staff and their specific professional qualifications, therefore it is difficult to analyze what specific cadres were available in different competence levels of the healthcare system (either primary, secondary or tertiary). Also, there is limitation in the range of data on the actual consumption of healthcare services. Therefore, it was not possible to analyze the consumption of health services in terms of how human resources were analyzed.

The direction of future research is to identify and investigate factors that could explain both the level and the trends in inequality in distribution of these healthcare resources across the country, focusing on factors to explain the shortage or inequity in the distribution of human resources. Studies examining the association between population health and the distribution of healthcare human resources could be further conducted to shed light on factors influencing population health.

7. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the equity to access to healthcare human resources as healthcare systems are laborious and therefore the workforce is treated as the most important of the healthcare system’s inputs. The healthcare services are delivered by people, therefore the equity distribution of human resources is so important, and the regional disparities in the allocation of healthcare resources might be a significant obstacle in preventing a part of the population from access to the basic healthcare services. Although the distribution of healthcare resources was more adequate for the population size with some little variation among the types of human resources, a striking difference was found in terms of the distribution per area. Inequities in human resources distribution are a serious threat to healthcare and sustainability. Geographical imbalances need to be taken into account when formulating the policy, rather than increasing simply the number of healthcare resources. Hence, this study can be used as a basis for healthcare policy formulation in order to correct the unequal distribution of healthcare human resources. By having such information, national government could monitor the nationwide distribution of healthcare human resources and provide some advice to regional policy makers (including NHF) in order to make proper adjustment. This would allow balancing of healthcare staff in different geographical areas and it also increases the efficient use of them. The planning for future supply of different types of healthcare staff as well as the admission limits for medical studies should also be based on such analysis, which would include more epidemiological and demographical differences between regions and macro-regions.

This study analysed certain group of human resources, the types of which were restricted by the availability of data. Additional studies can be conducted and they could incorporate other types of healthcare resources if they are available, including technology, infrastructure, and financing, to identify the overall circumstance of healthcare resources in Poland.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/5/2043/s1, Table S1: Theil index of main groups of healthcare human resources distribution in the year from 2010–2017; Table S2: Theil index of specialists distribution in the years from 2010–2017. Figure S1–S7: Lorenz Curve presenting the healthcare human resources according to level of need in the year 2010–2016.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Crisp, N. What would a sustainable health and care system look like? BMJ 2017, 358, j3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bem, A.; Siedlecki, R.; Prędkiewicz, P.; Gazzola, P.; Ryszawska, B.; Ucieklak-Jeż, P. Hospitals’ Financial Health in Rural and Urban Areas in Poland: Does It Ensure Sustainability? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I. The Food System—A Prism of Present and Future Challenges for Health Promotion and Sustainable Development; Triggering debate-White Paper; Health Promotion: Bern, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pantyley, V. Health inequalities among rural and urban population of Eastern Poland in the context of sustainable development. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017, 24, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabene, S.M.; Orchard, C.; Howard, J.M.; Soriano, M.A.; Leduc, R. The importance of human resources management in health care: A global context. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussault, G.; Dubois, C.-A. Human resources for health policies: A critical component in health policies. Hum. Resour. Health 2003, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce. Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/hrhreport2013/en/ (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Sowada, C.h.; Sagan, A.; Kowalska-Bobko, I. Poland Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; WHO Regional Office for Europe: København, Denmark, 2019; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Better Policies for Rural Development; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Diesendorf, M. Sustainability and sustainable development. In Sustainability: The Corporate Challenge of the 21st Century; Dunphy, D., Benveniste, J., Griffiths, A., Sutton, P., Eds.; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 2000; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ciegis, R.; Ramanauskiene, R.J.; Martinkus, B. The Concept of Sustainable Development and its Use for Sustainability Scenarios. Inz. Ekon. Eng. Econ. 2009, 2, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, G.; Popham, F.; McMaster, R.; Cumbers, A. Defining health and health inequalities. Public Health 2019, 172, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Making Fair Choices on the Path to Universal Health Coverage; Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alsan, M.; Bloom, D.; Canning, D. The Effect of Population Health on Foreign Direct Investment; NBER Working Paper no.10596; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004.

- Ríos-Osorio, L.A.; Zapata, W.A.S.; Ortiz-Lobato, M. Concepts Associated with Health from the Perspective of Sustainable Development. Saúde Soc. 2012, 21, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.S.; Allotey, P.; Reidapth, D.D. Sustainable development goals, universal health coverage and equity in health systems: The Orang Asli commons approach. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 2016, 1, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Arguing for Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization 2013. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204355 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Moreno-Serra, R.; Smith, P. The Effects of Health Coverage on Population Outcomes: A Country-Level Panel Data Analysis; Results for Development Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Universal Health Coverage and Health Outcomes; Final Report; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Panteli, D.; Sagan, A. Health Systems in Transition Vol.13 No. 8 Poland. Health System Review. 2011 European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/163053/e96443.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Whitehead, M. The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health. Available online: http://salud.ciee.flacso.org.ar/flacso/optativas/equity_and_health.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Bem, A.; Ucieklak-Jeż, P.; Siedlecki, R. The Spatial Differentiation of the Availability of Health Care in Polish Regions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 220, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, G.; Hunt, P.; Khosla, R.; Jaramillo-Strouss, C.; Fikre, B.M.; Rumble, C.; Pevalin, D.; Paez, D.A.; Pineda, M.A.; Frisancho, A.; et al. Health systems and the right to health: An assessment of 194 countries. Lancet 2008, 372, 2047–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/workforce/overview_en (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- The World Health Report 2000—Health Systems: Improving Performance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Becker, G.S. Human capital. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Scrutton, J.; Holley-Moore, G.; Bamford, S.M. Creating a Sustainable 21st Century Healthcare System; The International Longevity Centre–UK: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prada, G.; Grimes, K.; Sklokin, I. Defining Health and Health Care Sustainability; The Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, M. Towards Sustainable Health Care Organizations. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 5, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagała, A.; Klich, J. Planning of Polish physician workforce—Systemic inconsistencies, challenges and possible ways forward. Health Policy 2018, 122, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, S.; Goodman, A.C.; Stano, M. The Economics of Health and Health Care; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dussault, G.; Franceschini, M.C. Not enough there, too many here: Understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document on an Action Plan for the EU Health Workforce. SWD (2012) 93 Final. Strasbourg: EC; 18 April 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/workforce/docs/staff_working_doc_healthcare_workforce_en.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Wismar, M.; Maier, C.B.; Glinos, I.A.; Dussault, G.; Figueras, J. Health Professional Mobility and Health Systems in Europe. Evidence from 17 European Countires; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, E.; Batenburg, R.; Groenewegen, P.; Larsen, C.H. Bringing a European perspective to the health human resources debate: A scoping study. Health Policy 2013, 110, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroezen, M.; Dussault, G.; Craveiro, I.; Dieleman, M.; Jansen, C.H.; Buchan, J.; Barriball, L.; Rafferty, A.M.; Bremner, J.; Sermeu, W. Recruitment and retention of health professionals across Europe: A Literature review and multiple case study research. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, J.; Twigg, D.; Dussault, G.; Duffield, C.H.; Stone, P.W. Policies to sustain the nursing workforce: An international perspective. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, N.; Mwanri, L. The role of information technology in strengthening human resources for health: The case of the Pacific Open Learning Health Network. Health Educ. 2013, 114, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussault, G.; Buchan, J.; Sermeus, W.; Padaiga, Z. Assessing Future Health Workforce Needs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mantzavinis, G.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Lionis, C.h.; Trell, E. Geographical inequalities in the distribution of general practitioners in Sweden. Lakartidningen 2003, 100, 4294–4297. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorakis, P.; Mantzavinis, G. Inequalities in the distribution of rural primary care physicians in two remote neighboring prefectures of Greece and Albania. Rural Remote Health 2005, 5, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorakis, P.; Mantzavinis, G.; Rrumbullaku, L.; Lionis, C.; Trell, E. Measuring health inequalities in Albania: A focus on the distribution of general practitioners. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.; Wilkinson, D. Increasingly inequitable distribution of general practitioners in Australia, 1986–1996. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2001, 25, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Inoue, K.; Bowman, R.; Kajii, E. Self-employment, specialty choice, and geographical distribution of physicians in Japan: A comparison with the United States. Health Policy 2010, 96, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravelle, H.; Sutton, M. Inequality in the geographical distribution of general practitioners in England and Wales 1974–1995. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2001, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallikadavath, S.; Singh, A.; Ogollah, R.; Dean, T.; Stones, W. Human resource inequalities at the base of India’s public health care system. Health Place 2013, 23, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdenee, O.; Paramita, S.A.; Yamazaki, C.h.; Koyama, H. Distribution of health care resources in Mongolia using the Gini coefficient. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbanikhah, F.; Moradi, R.; Mazaheri, E.; Shahbazi, S.; Barzegar, L.; Karyani, A.K. Trends of geographic distribution of general practitioners in the public health sector of Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Mobaraki, H.; Hassani, A.; Kashkalani, T.; Khalilnejad, R.; Chimeh, E.E. Equality in Distribution of Human Resources: The Case of Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42 (Suppl. 1), 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sefiddashti, S.A.; Arab, M.; Ghazanfari, S.; Kazemi, Z.; Rezaei, S.; Karyani, A.K. Trends of geographic inequalities in the distribution of human resources in healthcare system: The case of Iran. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 2607–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, S.A.; Yamazaki, C.h.; Koyama, H. Distribution trends of Indonesia’s health care resources in the decentralization era. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e586–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Si, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shen, C.h.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Unequal distribution of health human resources in mainland China:what are the determinants from a comprehensive perspective? Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y. Inequality trends in the demographic and geographic distribution of health care professionals in China: Data from 2002 to 2016. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, e487–e508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]