Abstract

Sport organizations across North America promote and claim deep commitments to environmental issues through sustainability performance signaling. These signals are conveyed through external associations or memberships (e.g., Green Sports Alliance) or internally (e.g., environmental reports and communications). However, researchers have not explored this communication strategy as it relates to environmental initiatives in sport nor compared environmental communications of sport organizations from the major professional sport leagues in North America. We analyzed the websites of 147 North American sport organizations and their associated venue websites for environmental performance signaling communications. We found that only one sport organization featured an environmental report on its website, and 42 sport organizations highlighted environmental initiatives through dedicated webpages on the respective team or venue’s website. Predominately, these communications focused on fan engagement initiatives (i.e., awareness, participation) but lacked goal setting, measurement metrics, or performance summaries. We discuss these themes, the implications, and recommendations for how sustainability performance signaling can be better leveraged in the North American sport sector.

1. Introduction

As of 2019, 86% of Standard and Poors (S&P) 500 companies published corporate sustainability reports as compared to 20% in 2011 [1]. The importance these companies placed on sustainability is also exemplified through the commitment of 200 companies to put “people before profits” at the Business Roundtable Conference [2]. Such platforms make it possible for corporations to not only plan and take action, but also to communicate their commitments to environmental sustainability (i.e., Business Roundtable) and the subsequent results of such efforts (i.e., environmental sustainability report). Stakeholders and various public groups are more likely to trust and support the actions of organizations across a wide range of business sectors, including sport, if a clear system of communication is available, providing both qualitative and quantitative information [3,4]. This process is known as sustainability performance signaling [5]. In other words, it is a process of demonstrating the organization’s commitment to sustainability through membership in various associations and through communication efforts (e.g., reporting).

However, the historical commitment to environmental sustainability in the sport sector is slower than other industries [6]. The progression of environmental performance in the sport sector is constrained by the apprehension of upper management [7,8]. More specifically, sport practitioners do not actively engage out of fear of failing to meet stakeholder (e.g., fan) expectations [9,10]. Yet, professional sport organizations, in particular, signal sustainability performance through organizational memberships to groups like the Green Sports Alliance [11] or as signatories of the UNFCCC’s Sports for Climate Action Agreement [12]. Therefore, sport organizations can hide behind the perceived legitimacy of these organizations while potentially greenwashing and participating in sporadic environmental sustainability activities, requiring minimal efforts [13,14]. To that end, it is necessary to go beyond these memberships and signatories to examine the depths of these commitments, which could be verified through formal organizational communications and websites.

Thus, this exploratory study builds on the aforementioned research, by examining the websites of professional sport organizations in North America (i.e., NFL, MLB, NBA, MLS, and NHL) with regards to their sustainability performance signaling. The purpose of this paper was to further understand these sport organizations’ commitment to environmental sustainability by examining the degree to which each organization publicly releases information on their website regarding their efforts and to categorize the content of those communications and disclosures rather than through collective league wide reports. Such an examination will be the first to determine North American sport organizations’ sustainability performance signaling through action rather than empty public signs of commitment such as memberships and associations with different groups (e.g., Green Sports Alliance); and in turn, this inquiry will demonstrate the value these organizations place on environmental sustainability by the level of detail and transparency provided when disclosing their environmental sustainability initiatives. Following this, the findings of these environmental sustainability communications are reviewed. Finally, the implications for the current state of environmental sustainability performance signaling of these North American sport organizations are discussed.

2. Review of Literature

Changes in the natural environment have become a focus of public and political discussions, with the media playing a central role in communicating and publishing stories covering these controversial issues [15]. Organizations have shifted from solely relying on the media to publicize their environmental initiatives to using the organizations’ website to communicate with stakeholders and shareholders to distribute information related to sustainability programs [16]. This direct channel of communication allows organizations to have a mechanism to sway brand perceptions and deepen relationships with stakeholders. Using the organization’s website as the platform for communicating sustainability enables managers to offer unfiltered messages in a process known as sustainability performance signaling [5].

2.1. Sustainability Performance Signaling

Marketing communications are more effective when consumers believe that they could be effective at solving the problem (e.g., environmental footprint of the organization) [17]. Communicating environmental sustainability efforts conveys the organizational commitment of such initiatives—a process known as sustainability performance signaling [5]. While such components of disclosure should portray a transparent assessment of past performance and goal setting for future performance, these communications vary widely as well as the reasons for signaling. For example, Kolk [18] evaluated worldwide trends in the frequencies of reporting and the contents of those reports. Kolk determined various motivations for producing such reports. These motivations include credibility and organizational reputation, benchmarking and performance evaluation, bottom line savings, and operational efficiency, among other. Similarly, Bellringer, Ball, and Craig [19] studied sustainability reporting by New Zealand organizations and found that organizations engaged in sustainability reporting for internal reasons (i.e., desires of upper management, internal stakeholder management, accountability). Overall, the researchers found that sustainability reporting was not motivated strongly by pragmatism and economic rationalism and was not an idealistic mindset to solve global issues.

Thorne and colleagues [14] demonstrated that there are implicit and explicit ways to communicate sustainability initiatives. Implicit initiatives focus primarily on industry standards or organizational values (e.g., recycling) while explicit are ways “organization communications are viewed as being part of the social responsibility of the company” [14] (p. 87) (e.g., offsetting carbon footprint) [20]. These communications nonetheless are reactive to such pressures to increase the value of the organization’s brand. To this end, the effectiveness (i.e., the response of receiver) of such environmental communications influence the organization’s reputation, its corporate social position, and even valuation [5,21]. If these factors are considered, then the effectiveness would be greater from company-controlled (e.g., company’s website) communication than for third-party communication (e.g., media) [21] as way to convey a legitimate message.

Aerts and Cormier [22] explored environmental reporting as a way to increase organizational legitimacy. They concluded that organizations use sustainability disclosure to react to public pressure and inform relevant stakeholders that the organization’s behavior is appropriate and desirable to safeguard the environment. Legitimacy is thereby influenced by the depth and quality of reporting. In other words, a positive connection between the content of environmental communication (i.e., report) and environmental performance contributes to validating the organization’s efforts, thus making them more believable and views them as a legitimate authority on such issues. Environmental reporting is not only considered a way to increase legitimacy but to market (i.e., signal) the organization’s environmental values [23]. As indicated in the work of Allen [24], there are three types of legitimacy: pragmatic, moral, and cognitive. Stakeholders tend to favor organizations with a pragmatic type of legitimacy, especially when there is a potential for the stakeholder groups to personally benefit from the organization’s actions. As for moral legitimacy, it relates to the initiatives the organization is involved in and how these initiatives contribute to social welfare. Lastly, cognitive legitimacy relates to how well the public understands the actions taken by the organization. Regardless of the type of legitimacy an organization is striving for, it is imperative that a positive reputation is established as such reputation can protect the organization against crises [24]. The power of achieving legitimacy is not only expressed in protecting the organization, but it can also serve as a tool for influence.

When focusing on achieving environmentally legitimacy, it is important to point out the institutional approach which views entire sectors of organizations. Institutional beliefs and values are usually manifested through the process of isomorphism. There are three main forces driving organizational actions: coercive, mimetic, and normative. A combination of these forces constrain organizations into common business practices resulting in organizations that often mimic one another [25,26]. Most relevant are normative pressures, which can come from educational and professional authorities who set standards for ‘legitimate’ organizational practices; as well as from the media communications (e.g., press releases, website communication, social media) that reinforces desired and expected practices [27]. Communications and pressures from stakeholders foster shared value and meaning and may help to develop and guide behavior in organizations [28]. In other words, institutionalized business practices and norms concerning environmental sustainability (and subsequent communications) take root in the professional community or industry and are reinforced through isomorphism. However, the challenge with achieving legitimacy and environmental legitimacy in particular is that such legitimacy is based on the organization’s perceived environmental performance rather than on its actual performance [24]. Consequently, the credibility of the organization’s environmental communication is an important variable in its environmental legitimacy.

Implicit environmental reporting is driven by long-term [22] communicating of positive stories, successful sustainability initiatives, and excludes stories on the negative impact on the environment [23]. Skeptics speculate that environmental reports are a strategic move in public relations, considering the fact that most companies are not obligated by legislative pressure to communicate their environmental efforts. For example, Diouf and Boiral [29] examined the perceptions of stakeholders of the quality of sustainability reports. They found that practitioners believed that such reports reflect managerial strategy to highlight the positive outcomes of the organization while neglecting the negative outcomes. Stakeholders increasingly express interest in environmental issues, thus putting pressure on organizations to address these issues [23]. Organizations are motivated to disclose environmental actions, realizing that such reporting has the potential to influence their reputation and create a positive image [30]. This, in turn, legitimizes the organization’s behavior and shapes the stakeholders’ perceptions about the company.

Today more companies are publishing environmental reports as part of the other corporate disclosures. However, the quality and contents of these reports widely varies. Reports may differ on the measurement of similar initiatives and offer incomplete or vague data making it difficult to compare performances between organizations [31]. External communication about sustainability activities may vary significantly across organizations based on the communication channels, content, and frequency which in turn reflect on the company’s leadership and values towards environmental sustainability specific to how it allocates resource as a reflection of its organizational culture [32].

Du and colleagues [21] found that organizations receive better support from stakeholders and build a stronger public image by incorporating sustainability initiatives and reporting them to the public. It is imperative that stakeholders are aware of such activities as they play a big role in financial returns, whether direct or indirect [5]. In fact, such feedback between organizations and stakeholders can strengthen such efforts [33]. Therefore, it is critical for managers to have a deep understanding of what to communicate and where to communicate existing sustainability programs based on stakeholder preferences. Stakeholders are more supportive of initiatives that are consistent, have a good fit with the organization’s core values and aligned with their concerns [21].

Therefore, it is imperative that sport organizations emphasize this fit when reporting their environmental initiatives if they want to be viewed as credible and capitalize on the benefits received through various stakeholders’ relationships [34]. Specific to the sport industry, creating such connections with fans can increase fan identification through a new point of attachment [4,35]. This increased connection between the sport organization and fans decreases the likelihood that the fans will be more suspectable to fluctuations in on-field performance and maintain their devotion to the organization. Specifically, Casper and colleagues [4] found that lower identified fans increased their identity with the team because the sport organization communicated its environmental initiatives and performance (i.e., sustainability performance signaling). This fan segment consequently intended to attend more games, follow the team through media, and buy more merchandise. Thus, there is an economic benefit to sustainability performance signaling in sport.

2.2. Environmental Communication in Sport

The sport industry is not immune to the sustainability movement and pressures to engage in environmental sustainability [8]. As noted, McCullough and colleagues [36] characterized the progression of environmental sustainability in the sport sector in various waves. They also noted that sport organizations will typically implement front of house initiatives that are easily seen by fans (i.e., waste management, waste conservation, ballpark gardens) [36]. Predominantly, communications from sport organizations serve as a fan engagement effort to increase fan awareness and participation in the initiative. For example, many sport organizations in Major League Soccer (MLS) outline their goals for waste disposal and energy on their website [37]. More specifically, in relation to cleaning and maintaining the soccer facilities, the teams have set goals to reduce the cost of waste management and lower energy consumption along with a commitment to using biodegradable cleaning products and solar trash compactors. There is also a focus on issues related to transportation in locations where public transportation is easily accessible [37]. Although MLS organizations, in general, are implementing sustainability programs into their business practices, only a few teams are communicating a significant investment in such programs.

Researchers have explored not only the breadth of environmental initiatives, in general, and how the industry as a whole addresses environment sustainability initiatives [36], but they have also focused on how sport organizations communicate these environmental initiatives [38]. For example, Mallen and colleagues focused on MLS facilities, analyzing environmental communications on the website of each team’s venue. Their results indicated that sport venues communicated environmental initiatives programs related to renewable energy, resource minimization, and waste management. Additionally, some venues mentioned low-flow water fixtures, compostable cutlery, and the use of public transit (e.g., train, bus, share ride). Although the website communications indicated a variety of sustainability programs across the league, the communicated information did not contain any specific markers that could be used to quantify the information nor were they organized in a formal sustainability report.

To this end, Francis and colleagues [37] analyzed the same websites as Mallen et al [38] with the purpose of identifying the areas in which the teams were incorporating environmental sustainability. Francis et al found that existing environmental initiatives were grouped into the following categories: stadium design, efficiency and functionality, waste reduction, sustainable food options, community outreach, and waste management (i.e., composting, recycling). Again, such initiatives and environmental efforts were not organized in an overall or comprehensive sustainability report, but rather as side notes on the venue’s website.

In a different sport setting, Spector and colleagues [6] conducted a content analysis of American ski resorts’ environmental communications by examining the resorts’ websites. Some of the more common environmental sustainability issues related to skiing were concerns for vegetation and wildlife and artificial snowmaking. The most common projects among the sample revolved around recycling plastic and ski lift parts to installing energy-efficient light bulbs. Additionally, a significant emphasis was placed on transportation with resorts offering carpooling and shuttle services, and some even implementing policies against idling. Similarly, Chard and Mallen [39] found that environmental initiatives at four Canadian sport stadiums utilized renewable energy strategies (e.g., solar, wind, and biofuel energy). However, these venues provided no information on the measurement of renewable energy usage. Their results also indicated that the venues did not publish a renewable energy policy. Although sport organizations and sport facilities communicate their environmental initiatives, the available information is reported as a collective awareness campaign to raise awareness of customers concerning such initiatives and not for communicating specific targets or subsequent reporting of their environmental performance. Overall, there seems to be a disconnect between the actual environmental performance and the sustainability initiatives communicated on the websites, thus questioning the legitimacy and efficacy of such efforts.

2.3. Summary

Collectively, the body of research related to sustainability performance signaling in the sport sector is limited to venues and not focused on the sport organization’s comprehensive environmental impact. Granted, the most visible environmental impact occurs at the venue, there are other aspects of the event and of the team’s operations that are not taken into account [40]. Further, these communications are seemingly for more general awareness and fan engagement purposes. There is no indication that the venue websites are intended to convey the organization’s priority of integrating environmental sustainability or signaling their sustainability performance to anyone. At the very least, communicating such information concerning their environmental effort provides an opportunity to signal the importance that a sport organization places on its sustainability initiatives, beyond one-off press releases. Moreover, the various studies in this space are primarily focused on one league (e.g., MLS) or type of organization (e.g., ski resorts). Further inquiry is needed to examine how sport organizations across leagues communicate their sustainability initiatives. Thus, we propose the following research questions:

- RQ1: Where do sport organizations communicate their environmental initiatives and/or performance (e.g., formal report, dedicated webpage)?

- RQ2: What types of environmental initiatives are communicated?

3. Methods

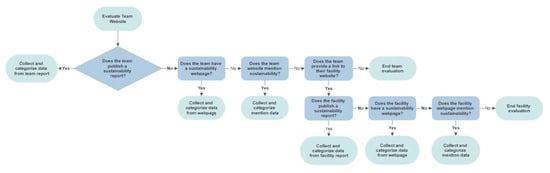

We utilize a multistep content analysis approach [41] to identify, collect, code, and analyze sustainability performance signaling through communications on the associated websites of the 147 professional sport teams in the five professional North American sport leagues (e.g., NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL, MLS). This multistep process was used to find the appropriate sustainability communications and information provided on the team or venue’s website. We developed this process because of the variety of ways the sport organizations shared their sustainability information, if at all. Specifically, we visually detail this process through a flowchart (see Appendix A, Figure A1). We also detail that process in the space below.

Each team’s individual website was reached through the corresponding league website (e.g., NFL.com, NBA.com, etc.). To begin, we systematically searched each team’s website (N = 147) for a cohesive sustainability report through the various tabs and links provided on the team’s website. If a report was found, the content of the report was recorded for later analysis. Specifically, we detailed the types of sustainable initiatives the team communicated through the published report. Alternatively, if no report was found, we conducted a secondary search of the team’s website for a dedicated sustainability webpage that highlighted information about the team’s environmental sustainability programs and initiatives. If a distinct webpage was not found, we subsequently reviewed the entire website for any mention of an environmental initiative. Such references, for instance, could include mentioning recycling in a facility A–Z guide, a few sentences on a team webpage (e.g., community page stating the organization values environmental sustainability) or a highlighted link to the league green program. Furthermore, if no reference to sustainability was found, the team websites’ search engine was used with the following keywords: sustainability, environment, green and greening.

Once the team website was thoroughly reviewed for sustainability communications, we looked for a hyperlink from the team’s website to the team or sport organization’s venue website. If a venue link could not be found, the review of the sport organization was concluded. However, if a direct viable venue link was provided, we deemed this a gateway between the sport organization and venue and continued our data collection. We then searched the corresponding venue website for a sustainability report or subsequent information related to environmental sustainability initiatives following the same detailed steps mentioned above (e.g., a dedicated website, mentions of environmental sustainability on the entire website). We collected the data from any facility published sustainability reports, webpages, and references to environmental sustainability initiatives found on the venue website. At this point, our data collection was concluded. For the purpose of the study, all sustainability signaling, and communication data were collected from the team or the corresponding venue websites. No external news sources were used.

Data Analysis

Data were then categorized and verified through member checking to ensure validity and reliability of the classification of data [42]. Through this process we analyzed the data by examining and classifying the content of environmental reports, community impact reports, dedicated webpages, and references to sustainability on the team and venue’s website. We specifically, noted what initiatives were highlighted (e.g., recycling, energy and water conservation), what community, educational, and engagement programs were offered (e.g., Green Weeks, Green Games, tree planting), and what partnerships (e.g., AEG1Earth), outside certifications (e.g., LEED), and memberships (e.g., Green Sports Alliance) were listed. We classified the data based on where it was found on each team or venue’s website respective to environmental communications (see Appendix A, Figure A1). We also categorized the various environmental communications with respect to the type of communication (e.g., fan engagement initiative communication, reporting communication, awareness communication). The specific results of our analysis are discussed below.

4. Results

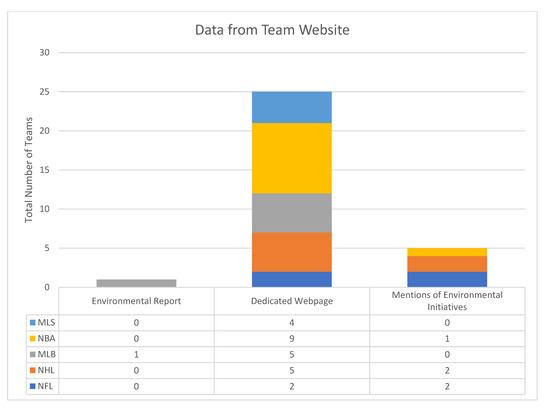

The 147 sport organizations in this study consist of 32 NFL teams, 29 NBA teams, 30 MLB teams, 31 NHL teams and 25 MLS teams (see Appendix A, Table A1). Based on our primary organizational search one (0.6%) team (i.e., Cleveland Indians) had a standalone sustainability report available on the organization’s website. We found that 25 (17.0%) sport organizations had distinct webpages dedicated to environmental initiatives. Eleven (7.4%) teams made a reference to environmental sustainability on their website (see Appendix A, Figure A1).

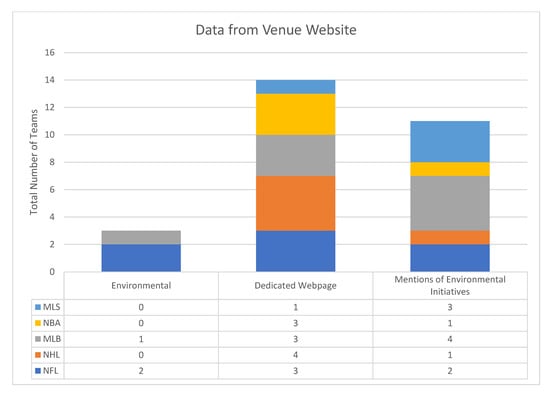

The second round of analysis searched the website of the organization’s venue and revealed that three (2.0%) teams (New York Jets, New York Giants, New York Mets) had a sustainability report linked on their associated venue’s website (e.g., MetLife Stadium, Citi Field). Thirteen (8.8%) of the venues websites had a dedicated webpage detailing their environmental sustainability initiatives. However, only eleven (7.5%) venue’s websites made an explicit reference to environmental sustainability (see Appendix A, Figure A2).

Categorical Results

Content of reports. Our analysis of all environmental communications data from sport organizations or venues’ websites identified three specific themes. First, sport organizations and venues are not communicating their environmental performance. It should be noted that this does not imply that sport organizations are not engaging in environmental sustainability initiatives within their organizations, but rather they are not reporting it. For the scope of this study, it is the lack of website reporting and communication that is the area of interest despite what one off communications initiatives (e.g., press release, news story) may be used to signal a team’s environmental initiative(s). There are limited examples from our sample of formal environmental reports on their team website (i.e., Cleveland Indians) or from their venue (i.e., New York Mets, New York Giants, New York Jets). The New York teams were legally required to file venue sustainability reports as part of their permitting processes by the Environmental Protection Agency—thus these are not voluntary reports. Moreover, these environmental reports focus on the environmental aspects surrounding the venue and the events hosted in the venue and not of broader team operations [40,43]. For example, the environmental report from the Cleveland Indians (2016) focuses solely on the operations of Progressive Field and the baseball games hosted in the stadium. The report does not include additional environmental impacts of environmental externalities (e.g., fan travel) or the team’s operations (e.g., team travel; spring training facility). The inclusion of such environmental impacts would provide a more robust and comprehensive assessment of the sport organization’s environmental impact [40].

Fan engagement. Second, environmental communications conveyed on the sport organization and venue’s dedicated webpages focused on fan engagement initiatives. That is, these communications were designed to raise awareness among stakeholders to increase participation in sport organization or venue’s environmental initiatives. Teams that hosted Green Games and Green Week communications dominated this category to educate and involve fans in sustainability initiatives. However, these communications focused on customer facing initiatives such as waste management (e.g., composting, recycling), waste reduction (e.g., decreased packaging), water conservation (e.g., low flow water features), and mass transit options. These communications seldom focused on the back of house environmental initiatives. One exception was the New York Yankees. This organization communicated its commitment to reduce its environmental impact (i.e., greenhouse gases, waste recovery, energy efficiency, air quality) and even pledged to offset unavoidable carbon emissions (e.g., fan and team travel) through carbon offsets. Despite these pledges, the Yankees did not communicate its current environmental performance (i.e., diversion rates, carbon emissions from various scopes, energy consumption, air quality).

We should reiterate that the National Hockey League (NHL) published an environmental report for the league and included sections for each team [44]. This report was not included in our analysis because it was featured on the league’s central website and was not published by individual sport organizations in the league. Though, we included this information because individual NHL teams highlighted and provided links to the league green program on their respective teams’ website. In this report, the league highlighted the environmental impact of the various venues, practice facilities and team travel. Thus, this was the most extensive report that we found. However, the focus of the report was from a league level and the data for individual sport organizations were not detailed. To its credit, the NHL stated specific limitations of their current sustainability report and outlined performance targets for the league and individual sport organizations that will be included in the next iteration of the report.

Third, the sport organizations that do not provide sustainability reports are engaged in environmental initiatives to varying extents based on the sustainability communications provided by the organization on the team website. Interestingly, all five professional sport leagues in North America are members of the Green Sports Alliance (GSA), a sport and environmental clearinghouse organization [45]. However, only 68.7% (N = 101) of the sport organizations in our study are listed as members of the Green Sports Alliance. Of the GSA member organizations, 29.3% (N = 43) teams or venues feature sustainability reports or dedicated webpages to their environmental initiatives. Membership to the Green Sports Alliance is a sustainability performance signal communicating the organization’s commitment to environmental causes. We would expect to see a deeper commitment from these member organizations and feature additional environmental performance signals through direct communications, but our findings ran contrary to this expectation. Our results suggested signaling environmental performance through membership in the Green Sport Alliance may not translate to action or increased communication via websites by its associated members.

It is unclear why these member organizations do not provide more comprehensive or detailed environmental communications. However, researchers have previously suggested that there are not adequate pressures put on sport organizations or leagues, primarily in North America, to be more environmentally responsible [9]. Moreover, sport practitioners are incentivized to minimize their environmental impacts while maximizing their economic benefits. Such motivations cause sport organizations to gloss over the expansive nature of their environmental impacts in the production and consumption of their product [40]. While professional sport organizations have made notable efforts and strides to be more environmentally sustainable [36], teams are not reporting on such efforts perhaps indicating the team’s motivation for publicity rather than altruistic care for the environment. Further, others [36,45] have suggested that the advocacy groups like Green Sports Alliance may serve the interests of their members more than aggressively advancing environmentally sustainable sport organizations.

5. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the sport sector in North America is certainly behind other business sectors when it comes to sustainability performance signaling communications. Scholars [46,47,48] have demonstrated the breadth of sustainability efforts in the sport industry; but, as our findings indicate, the depth of these environmental initiatives are limited to raising awareness or educating stakeholders, mainly fans, about the organization’s environmental efforts. Perhaps this is not surprising given the low awareness levels of environmental initiatives reported in previous research [4,9,35]. The lack of environmental performance signals challenges the depiction that sport organizations send through external signals like memberships to sport and environmental focused organizations (e.g., Green Sports Alliance), environmental certifications (e.g., LEED; Council for Responsible Sport), and signing international commitments (e.g., Sports for Climate Action Framework). That is, the internal organizational efforts, or at the very least the communication of those efforts, do not seem to align with the external signaling of these organizations.

These external signals (i.e., memberships, certifications, agreements) do not guarantee that a sport organization will continue their environmental commitments internally. This is to say, a higher expectation for sport organizations that make such external efforts to promote their environmental initiatives and report on them. As it stands, sport organizations signal the value of such efforts, but do not convey the depths of their stated commitments through action. For example, if a sport organization prioritizes its commitment to environmental sustainability through memberships, certifications, and international commitments it would be reasonable to expect this same organization to publicly declare its intention to state its current environmental performance on a variety of initiatives (e.g., carbon emissions, energy consumption, waste diversion rates).

Unfortunately, the largest and most valuable sport organizations in North America fall short of signaling their prioritization of environmental sustainability. Thus, more work is necessary among sport practitioners to develop these environmental efforts internally and advance the initiatives to the point where their performance can be tracked and reported [36]. To this end, Trendafilova and McCullough [45] recommend that partnerships between sport practitioners and academics can help develop these strategic plans and advance environmental initiatives to the point of public reporting. These collaborations can have a meaningful and significant impact on the advancement of promoting environmental sustainability in and through sport [49].

5.1. Practical Implications

As part of this communication process, it is important for organizations to have a system in place where they monitor the success of their sustainability initiatives or lack thereof. Researchers have indicated that some organizations that have a high level of effort have a low level of results, questioning whether this is due to a lack of monitoring during the implementation stage [50]. Monitoring could be improved by having a standardized format of gathering data based on quantifiable targets that can be easily measured. The long-term implications of all these factors related to the communication of sustainability efforts could lead to a larger and more diverse pool of stakeholders interested in investing in sustainability programs. Additionally, environmental reporting has the potential to benefit organizations by determining stakeholders’ desires and by evaluating and improving the internal environmental management system.

Environmental reports can offer practitioners the appropriate platform to identify the organization’s goals and provide updates to stakeholders about their progress towards those goals. However, preliminary reports indicate that sport practitioners are hesitant to promote or discuss any environmental sustainability initiative [10]. To this end, if an organization is deemed legitimate in their efforts, sustainability initiatives can attract new fans and deepen the identity of current fans [4]. Whether these reports are released publicly, sport and entertainment practitioners can evaluate the environmental impact of their facilities, events, and organizational operations. Teams should be collecting such data to simply improve the performance and efficiency of their sport organization or venue operations. Lack of efficiency means waste—wasted finances that hurt the bottom line [8]. Thus, annual reviews of the sport organization and venue’s operations can lend well to improving environmental performance in general, but can also lead to the accountability of environmental performance if signaled to the public.

5.2. Recommendations

Sport practitioners should examine common practices in other industries to best leverage the benefits of communicating environmental sustainability initiatives. As McCullough and Cunningham [8] conceptually indicated and others have empirically demonstrated [4,9], there are financial (e.g., increased patronage) and social (e.g., increased goodwill) for a sport organization when they implement environmental focused operations. Researchers have recommended deeper collaborations between practitioners and academics to best identify which environmental initiatives will resonate with fans and to better align environmental sustainability campaigns with fan psychographics to maximize their participation [35]. This process is known as a materiality assessment, which determines the preferences for various initiatives comparing multiple stakeholder groups (i.e., internal v. external).

However, as sport organizations are already engaged in initiatives, it would best suit them to release data specific to their performance. A recent example of a missed opportunity to properly signal a sport organization’s dedication to environmental sustainability can be exemplified through the Seattle Sounder’s notoriety gained by claiming to be the first ‘carbon neutral’ sport organization in North America. However, the team, or the environmental consulting group, has not published any reports detailing their methodology, data, results, and determination for how carbon mitigation would occur. The only information provided from the team was a press release and pictures of team members planting seedling trees in an already established forest. Yet, the Seattle Sounders are held in the highest regard as one of the most progressive sport organizations in North America with regards to environmental sustainability without providing background information.

We would recommend that organizations that promote such ambitious claims and efforts to reduce their environmental impact would, in fact, support those claims with transparency and third party reports. As it would seem, upon reflection of the one-off story, the Sounders sought the instant lift in their brand by signaling their values without providing adequate substance (e.g., reporting on carbon Phase 1–3 emissions, calculations for carbon mitigation, goals for future). Sport organizations should leverage the data on hand to benchmark and publicly disclose their commitments to reducing their environmental impacts whether that be for waste diversion, carbon emissions, energy usage, team travel, fan travel, or facility operations.

5.3. Future Research

Future research should focus on the expectations and response various stakeholder groups have towards the environmental initiatives of sport organizations. Prior work in this space has evaluated whether or not fans believe sport organizations are responsible for addressing their environmental impact [4,9]. Further work is needed to evaluate the fan response to sustainability performance signaling and its impact on the sport organization’s brand combining this focus with Trail and McCullough’s [35] framework. Further, researchers should explore the impact of such communications or signals as they relate to increased financial returns. Lastly, it would also be worthwhile to explore the perception of stakeholders as to whether or not sport organizations are viewed as legitimate conduits of environmental messages (i.e., promoting environmental behaviors).

6. Conclusions

The examples of what sport organizations do in their community to reduce their environmental impact are well documented in the popular press and have been examined in academic research. However, there is a paradox between the breadth of these initiatives and the lack of reporting. The lack of reporting presents many questions worthy of exploration for academics and areas of consideration for practitioners. For example, both academics and practitioners can examine whether sport organizations, or their own organization, have the capacity to properly communicate the environmental performance of their organization and its initiatives in a variety of ways including press releases and environmental reports. Moreover, it is necessary to further examine the reactions of current fans, prospective fans, community members, and other stakeholders to such environmental sustainability signaling effort. Also, it is necessary to understand why stakeholders do not demand or require sport organizations to do more concerning sustainability efforts and subsequent (lack of) reporting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P.M. and J.P.; Data curation, J.P.; Formal analysis, B.P.M. and J.P.; Methodology, B.P.M.; Project administration, B.P.M.; Supervision, B.P.M. and S.T.; Writing—original draft, B.P.M. and J.P.; Writing—review & editing, B.P.M., J.P. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Content analysis flowchart for data collection.

Figure A2.

Categorical totals from team websites.

Figure A3.

Categorical totals from team affiliated venue websites.

Table A1.

Results of website analysis.

Table A1.

Results of website analysis.

| League | Teams | Team Website | Venue Website | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Report | Dedicated Webpage | Mentions of Environmental Initiatives | Environmental Report | Dedicated Webpage | Mentions of Environmental Initiatives | ||

| NFL | 32 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| NHL | 31 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| MLB | 30 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| NBA | 29 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| MLS | 25 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 147 | 1 (0.6%) | 25 (17.0%) | 5 (7.4%) | 3 (2.0%) | 13 (8.8%) | 11 (7.5%) |

References

- Governance & Accountability Institute. Flash Report: 86% of the S&P 500 Companies Published Corporate Sustainability Reports in 2018. Available online: https://www.ga-institute.com/press-releases/article/flash-report-86-of-sp-500-indexR-companies-publish-sustainability-responsibility-reports-in-20.html (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Business Roundtable. Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of the Corporation to Promote ‘an Economy that Serves all Americans’. Available online: https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Burke, J.J.; Clark, C.E. The business case for integrated reporting: Insights from leading practitioners, regulators, and academics. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.; Pfahl, M.; McCullough, B.P. Is going green worth it? Assessing fan engagement and perceptions of athletic department environmental efforts. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2017, 9, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Kleffner, A.; Bertels, S. Signaling sustainability leadership: Empirical evidence of the value of DJSI membership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, S.; Chard, C.; Mallen, C.; Hyatt, C. Socially constructed environmental issues and sport: A content analysis of Ski Resort Environmental Communications. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.; Pfahl, M.; McSherry, M. Athletics department awareness and action regarding the environment: A study of NCAA athletics department sustainability practices. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Cunningham, G.B. A conceptual model to understand the impetus to engage in and the expected organizational outcomes of green initiatives. Quest 2010, 62, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.; Pfahl, M.; McCullough, B.P. Engaging fans in intercollegiate sustainability efforts: Understanding the environmental perspectives and actions of sport fans. J. Issues Intercoll. Athl. 2014, 7, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Sport Business Journal. ‘Green’ Survey Results: Green Sports Alliance Survey Shows that Sustainability Efforts Continue to Catch on in Sports, but Cost Perceptions Thwart Growth; American City Business Journals: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Green Sports Alliance. About. 2018. Available online: http://greensportsalliance.org/about/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- United Nations. Sports Representatives and the UN Pitch for Climate Action. Available online: https://cop23.unfccc.int/news/sports-representatives-and-the-un-pitch-for-climate-action (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Miller, T. Greenwashing Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, L.; Mahoney, L.S.; Cecil, L.; LaGore, W. A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 350–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen, T.; Shapiro, M.A. The US news media, polarization on climate change, and pathways to effective communication. Environ. Commun. 2018, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacchezzini, R.; Melloni, G.; Lai, A. Sustainability management and reporting: The role of integrated reporting for communicating corporate sustainability management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C. The baby is sick/the baby is well: A test of environmental communication appeals. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. A decade of sustainability reporting: Developments and significance. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 3, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellringer, A.; Ball, A.; Craig, R. Reasons for sustainability reporting by New Zealand local governments. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2011, 2, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore-Baldwin, M.L.; McCullough, B.; Quatman-Yates, C. Shared responsibility and issues of injustice and harm within sport. Quest 2017, 69, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, W.; Cormier, D. Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, P. Communication in corporate environmental reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2002, 9, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Legitimacy, stakeholders, and strategic communication efforts. In Strategic Communication for Sustainable Organizations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 61–104. [Google Scholar]

- Trendafilova, S.; Babiak, K.; Heinze, K. Corporate social responsibility and environmental sustainability: Why professional sport is greening the playing field. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, T.; Hinings, B. Institutional pressures and isomorphic change: An empirical test. Organ. Stud. 1994, 15, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate communication and impression management–new perspectives why companies engage in corporate social reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hąbek, P.; Wolniak, R. Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, A.H.; Larya, N. External communication about sustainability: Corporate social responsibility reports and social media activity. Environ. Commun. 2018, 12, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de Castro, G.; Amores-Salvadó, J.; Navas-López, J.E. Environmental management systems and firm performance: Improving firm environmental policy through stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, G.T. Marketing Sustainability Through Sport; Sport Consumer Research Consultants LLC: Seattle, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, G.T.; McCullough, B.P. Marketing sustainability through sport: Testing the sport sustainability campaign evaluation model. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Pfahl, M.; Nguyen, S. The green waves of environmental sustainability in sport. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1040–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Norris, J.; Brinkmann, R. Sustainability initiatives in professional soccer. Soccer Soc. 2017, 18, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallen, C.; Chard, C.; Sime, I. Web communications of environmental sustainability initiatives at sport facilities hosting Major League Soccer. J. Manag. Sustain. 2013, 3, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chard, C.; Mallen, C. Renewable energy initiatives at Canadian sport stadiums: A content analysis of web-site communications. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5119–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Watanabe, N.M. Measuring externalities: The imperative next step to sustainability assessment in sport. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 1–10, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, B.P.; Kellison, T.B. Routledge Handbook of Sport and the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Hockey League. Sustainability Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.nhl.com/info/nhl-green (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Trendafilova, S.; McCullough, B.P. Environmental sustainability scholarship and the efforts of the sport sector: A rapid review of literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1467256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. Corporate social responsibility in sport: An overview and key issues. J. Manag. 2009, 23, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Kent, A. Investigating the role of corporate credibility in corporate social marketing: A case study of environmental initiatives by professional sport organizations. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Babiak, K.M. Beyond the game: Perceptions and practices of corporate social responsibility in the professional sport industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Trendafilova, S. Industry-academic collaborations to advance sustainability. Sport Entertain. Rev. 2018, 4, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, J.; Stevens, J.; Mallen, C. The IOC: An interpretation of environmental sustainability, 1994–2008. Sport Soc. 2011, 14, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).