1. Introduction

Besides the core product (or service) itself in a for-profit environment, it is required to determine other important drivers for business success, which can have impacts on efforts towards a sustainable business. Business success is made of many factors which are important to efficiency and overall effectiveness of a company, especially in the case of a small or medium sized one, which can be significantly different from doing business in large corporations. Looking through a bigger scale, participation in a supply chain can also make a difference in the level of impact which logistics capacities create relating to key business performances. Previous studies on the topic of logistics management as a business function in small and medium sized companies (excluding entrepreneurs and non-profit organizations) were mostly focused on topics related to transport, supply chain organization and control, warehouse management and reverse logistics.

Not many existing studies seem to be focused on the fact that owning of logistics capacities can represent a key enabler regarding business performance (in terms of efficiency and effectiveness). The results of worldwide research on small and medium sized businesses, conducted by experts from European Commission [

1], referred to unpredictable market conditions as one of the major external challenges for overall sustainability of the SME sector across Europe. Rezaee [

2] and Lopez-Perez [

3] defined economic, social, and environmental dimensions as key dimensions for differentiating sustainability of SMEs, by outlining the importance of the economic dimension (and indicators such as financial statements). Economic sustainability in the context of an SME was investigated in research by Doane and Macgillivray [

4], and it can be defined as an effective use of assets within a business in order to allow and ensure its short-term profitability and long term survival. Cantele and Zardini [

5] expand this by defining the strategic relevance of economic sustainability, in terms of SME competitiveness on the market. Finkbeiner [

6] introduced internal and external criteria (or factors) influencing economic sustainability of a company.

Studies dealing with theory and observing existing and potential trends regarding small and medium sized businesses have been narrowed, referring mainly to the EU, and then to Republic of Serbia specifically. Consultant company Price-Waterhouse-Coopers (PwC) [

7] reported that most surveyed European SMEs predicted steady or rapid economic growth until 2024, but it is unclear whether this shall be true regarding Serbia.

On the other side, relating to question on current trends in world literature, this paper empirically investigated the important topic in the form of a survey, which was defined with support of experts in the field of small and medium sized businesses (see

Appendix A for more details). The results and discussion part of the paper attempted to identify similar conclusions, but with clearly analyzed findings which are related to the current state of the Serbian economy (as a country in development). The final part of this research summarized and defined future research efforts. For the purpose of identifying a possible gap in existing literature, two research questions have been formulated:

Which business factors (external and internal) determine efforts of an SME towards economic sustainability, in terms of indicators of business performance?

To what extent are business performances different, while observing between SMEs which have logistics capacities, and those which do not?

The answer to these questions lies within a systematic literature review, and it demands conducting empirical research, to fully examine different dependencies between indicators of business performance, key business factors, and other important factors regarding logistics management (participation in one or many supply chains, ownership of logistics capacities, internationalization efforts). Based on defined research questions, it is possible to set the main objective of the paper—to identify key correlations for indicators of business performance in SMEs, depending on logistics capacities (through having or outsourcing of capacities).

A clear gap in existing literature has been discovered with this paper, regarding key influences on economic sustainability of an SME. Current literature about logistics management in SMEs does not consider logistics capacities as an important factor, and specifically ownership over logistics capacities, as one of key impacts on economic sustainability.

Based on the need for better describing of influences on economic sustainability of an SME, it is necessary to thoroughly review existing literature about previous highlights and similar attempts to identify the research gap. Firstly, theoretically defining key business factors which relate to internal and external profile of an SME is needed. Next, the financial parameters that are suitable for comparative analysis of SME business performance should be determined, with the intention of exploiting the most out of the empirical research within the defined research framework. Additionally, this research should explain which parts of the defined literature gap have to be further analyzed, because it was not possible within this research.

The following section presents previous findings on two main topics: key business factors affecting an SME (with extension towards ownership over logistics capacities as a factor), and key influences on economic sustainability of an SME.

2. Theoretical Background

Definition of supply chain management in a small or medium sized company is often narrowed to consideration of several key dimensions (business/economic, environment, social impact), as described by Kot [

8]. Opposed to this (and out of scope of this research), within large companies, existing literature considers a whole variety of logistics functions (purchasing, warehousing, packaging, sales, flow of information, and materials). When witnessing efforts of an SME to succeed in a very competitive market, it is often concluded that expansion to new markets (Hollenstein [

9]) and enlargement of internal operational capacity (Willems and Coq [

10]), can establish as main sources of profitability. Logistics capacities, in terms of supply chain management, can be defined as all economic, infrastructural, and technical means of any type, size, and structure, all of which are available for an unlimited period of time, to be effectively manipulated towards achieving business success, as it was previously analyzed by Grose-Brockhoff [

11].

Still, after reviewing current literature, the influence of logistics capacity as one of main enablers of successful business performance is not clearly analyzed (Villa and Antonelli [

12], Szegedi [

13]). The focus of this paper is on identifying key correlations which can contribute to describing SMEs which have logistics capacities, compared to those which outsource logistics capacities, in order to maintain economic sustainability of their business performance.

2.1. Key Internal and External Business Factors Affecting an SME

It is interesting to analyze trends from different periods (Katsikeas [

14] and Pickernell [

15]) and determine whether results can depend on company size. It was performed by considering internationalization of business activities (towards regional or continental level). Regarding the share of exporters in the most developed markets of Europe, differences based on the company size, one can see that the share of companies which have internationalized business activities decreases with the growth of number of employees. In other words, the success of a small company is more dependent on the success of logistics as a driver of export activities. Han [

16] supplemented these statements, with evidence of government support programs for small exporters, in the form of information on the resources and capacities of other exporting companies. There is clear space for analyzing whether exporting activities (as an external business factor) and ownership over logistics capacities (as an internal business factor) can drive business performances of an SME.

With the intention of properly understanding the context of logistics management in a SME surrounding, similar research topics were investigated within this paper. Current trending topics define logistics function in SMEs as of increasing importance, as it was defined by Taschner [

17], oriented towards integration with other business functions (Gelinas [

18]), and focused on driving internationalization efforts of the business (Neupert [

19]). To supplement this, whether a clear difference can be found between companies, doing business alone or businesses who are participating in a supply chain, should be questioned. Additionally, this analysis should be separated into companies involved in only one supply chain, compared with companies involved in two or more chains, in order to determine whether multiple distribution channels can damage business performances of an SME.

First, the main difference can be potentially found when analyzing the path from the production site (gathering of raw material) all the way to the final customer, since smaller businesses tend to react quicker to variations in demand (Sorak and Dragić [

20]). On the other side, Kot and Onyusheva [

21] find that focus on type of end customer (private or state owned, domestic or foreign) and overall cost reduction, should be the main pillars for SMEs involved in supply chains. A second difference can be found when examining efficiency, quality, and reliability within SMEs involved in a supply chain, since Isenberg [

22] reports that small businesses are striving to ensure visibility, while attempting to acquire large supply contracts (with recurring needs), in order further stabilize and grow their business. According to Arend and Wisner [

23], participation in a supply chain can expose the small business with more formalized procedures, and this can lead to losing uniqueness of the small business. A logical conclusion following these studies can be to analyze whether smaller companies are more dependent on logistics capacities than medium sized ones.

According to a research by Olah [

24], more than two thirds of SMEs in Serbia (and countries of Visegrad group) fail on their sustainability efforts, since they do not manage to survive longer than the first five years of business. Rahman [

25] defines logistics infrastructure within an SME (or logistics capacity) as one of the main obstacles for successful participation in a supply chain.

When considering the reasons for outsourcing logistics capacities in a small business, Core group [

26] outlines the most important facts: “A third party logistics provider will have a vast network, long standing partnerships and available resources that your company may not have. A logistics provider has a system in place to ensure it is cost effective and each step of transportation is executed with proper care. Having a workable system in place is not something every company can do. It takes time, effort and resources, and this is beyond the scope of work small companies are capable of doing.”

After first part of literature review, a clear distinction can be made between internal and external business factors:

Internal—related to company size, logistics management, form of fulfillment of customer needs, participation in supply chains;

External—related to internationalization efforts, market share, form of placement on foreign market, position within production chain (from raw material to final placement).

In the continuation of this paper, it is envisioned to theoretically determine and analyze key indicators of business performance that represent economic sustainability of an SME.

2.2. Key Indicators of Business Performance in SMEs

Al Tit [

27] categorized most important indicators for success of SMEs, by introducing business performance indicators, business characteristics, and business environment. Formisano [

28] studies sustainability from a business perspective, identifying financial performance as relevant for comparison between businesses. Berger Douce [

29] outlined the financial performance of SMEs, measured through several business performance indicators, such as financial health (solvency, liquidity), quality of delivered products, and the ability to generate enough new income (profitability). Ciobanu [

30] added, by deepening financial performance indicators which influence profitability of SMEs, while Margaretha [

31] investigated factors of SME profitability with regression analysis, outlining company size and growth rate. This study has the potential to involve several (most important) indicators of business performance, and to process it with regression analysis. Additionally, it would be useful to compare indicators of business performance depending on company size (this would help in questioning whether smaller companies are more dependent on larger companies, when trying to succeed on the market).

Ekanem [

32] found that liquidity management in small businesses presented the most problematic impact on business performance, so this fact can present itself as a limitation in terms of determining key correlations with this indicator of business performance. Additionally, Kontuš and Mihanović [

33] explored dependencies between profitability and liquidity in Croatian SMEs, discovering a correlation between cash flow trends and mentioned indicators of business performance. It is unclear how to determine sustainability of companies which have problems dealing with participation in a supply chain (with numerous companies). Therefore, they depend on profitability and liquidity performances of other connected partners.

Ključnikov and associates [

34] analyzed insolvencies of SMEs in the Central European region, discovering dependencies between solvency of an SME and payment discipline of their key customers. Following this, it would be beneficial to explore dependencies, between sales share to different types of customers, and indicators of business performance. Falkner and Hiebl [

35] assessed a total of 27 papers, dealing with SMEs and risk management topics, and they outlined solvency problems as one of key risks for SME survival (economic sustainability). It is not clear whether survival can also depend on solvencies of different companies in a supply chain, as it was questioned above with profitability and liquidity.

Other studies focused more on business performance indicators—Malesios [

36] investigated turnover and business growth, while Shihadeh [

37] determined credit risk of SMEs, as business performance dimensions of sustainability in an SME. On the other side, Lopez-Perez and associates [

3] discovered that sustainability is influencing overall company value, brand, and reputation, well beyond economic measures. Since this research is dealing with the economic aspect of SME sustainability, these factors are out of scope of this research.

Following this overview on key influences on SME sustainability, it can be recapitulated that:

Examination of influences must balance between short-term business success, as well as long term survival of the company;

The strongest impact of internal and external business factors included only a few, most important indicators of business performance, such as liquidity, solvency, and profitability.

Now follows development of main and auxiliary research hypotheses, in order to design the empirical part of research.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Following the review of existing literature about the topic of logistics management in an SME, and possible factors which can have an impact on its business performance, it can be summarized that existing literature focuses on subjects such as economic sustainability of SMEs involved in a supply chain (Jin [

38]), logistics capacity of SMEs (Gecse [

39]), internationalization of business activities to new markets (Sen and Haq [

40]), while certain authors covered market profile of the company and portfolio based factors of business (Hao et al. [

41]). Meanwhile, previous literature findings, dealing with business performance measures in SME surrounding were mainly focused on financial (Zorn and associates [

42]) and non-financial indicators (Leković and Marić [

43]).

Having in mind this revealing information, it can be surely legitimate to state that the main subject of this research should further exploit topics related to sustainability efforts of SMEs, such as the previous work by Burlea-Schiopoiu [

44], through examination of a real-world business environment. More specifically, key business factors should be examined (potentially participating in the research survey). After literature review, and before the quantitative part of the research, a focus group was organized, to ensure that the summary of the literature review was properly discussed. The focus group consisted of experts from various industries. Conclusions formed as a joint product of the literature review and consequential discussion with experts was structured within the planned research survey. Following the literature review, key dimensions were defined, which determined possible impacts of logistics capacity (of an SME) across different efforts towards a sustainable business:

Internal/external factors related to business (Debarliev and Janeska [

45]),

Business performance (Blackburn [

46]),

Participation in a supply chain (Logistics bureau [

47]),

Internationalization of sales activities (Laghzaoui [

48]).

Having this in mind, the main objective of this study can be defined as:

To be able to fully explore and elaborate the main research goal, it is necessary to analyze a list of factors influencing the business outcome. Considering measurability and scalability with appropriate quantitative methods and techniques, it was decided that key correlations between business factors and business performance (in two different groups of SMEs) should be analyzed through linear regression, as it represents an integral process of discovering statistically significant inference and correlations (James [

49]). The mentioned plan of research should be able to adequately test and validate the main research goal and research question, as well as to ensure a broader perspective in analysis of logistics management in SMEs.

Therefore, the main hypothesis can be defined, to provide an answer to the main research question:

Main hypothesis: It is possible to determine key correlations between internal and external factors of a business, which are directly correlated to indicators of business performance of an SME.

Looking forward to deeper exploitation of the main hypothesis, the authors have defined an auxiliary hypothesis which could help justify the main research question:

Auxiliary hypothesis: There is a statistically significant difference between indicators of business performance of SMEs who own or lease logistics capacities.

The auxiliary hypothesis should provide answers regarding whether it is possible to determine a statistically significant difference of correlations between business factors (internal and external) and indicators of SME business performance, depending on the fact that they own logistics capacities or outsource them. After the empirical confirmation, a discussion about findings with previous research follows.

The next section presents the results of qualitative research, methodology of variable definitions, and questionnaire development prior to definition of quantitative research, and it is followed by findings and discussion from the empirical research. Additionally, the following section serves as a testing plot for reaching the general objective of this paper.

3. Methodology

The methodology used (following the nature and purpose of this research) is based on a mixed methods approach. The methodology was formulated by following previous concepts defined by Creswell and Clark [

50], and as well as Almeida [

51]. This can serve as an advancement of the discipline as these approaches provide richer understanding and more robust explanations of SME business management phenomena. Similar method approaches have already been effectively used in research papers considering economic sustainability and SME business management topics, such as in Mahmood [

52], and Curado [

53]. The methodology of this investigation consists of three separate stages: qualitative research, development of questionnaire and variables, and research sample.

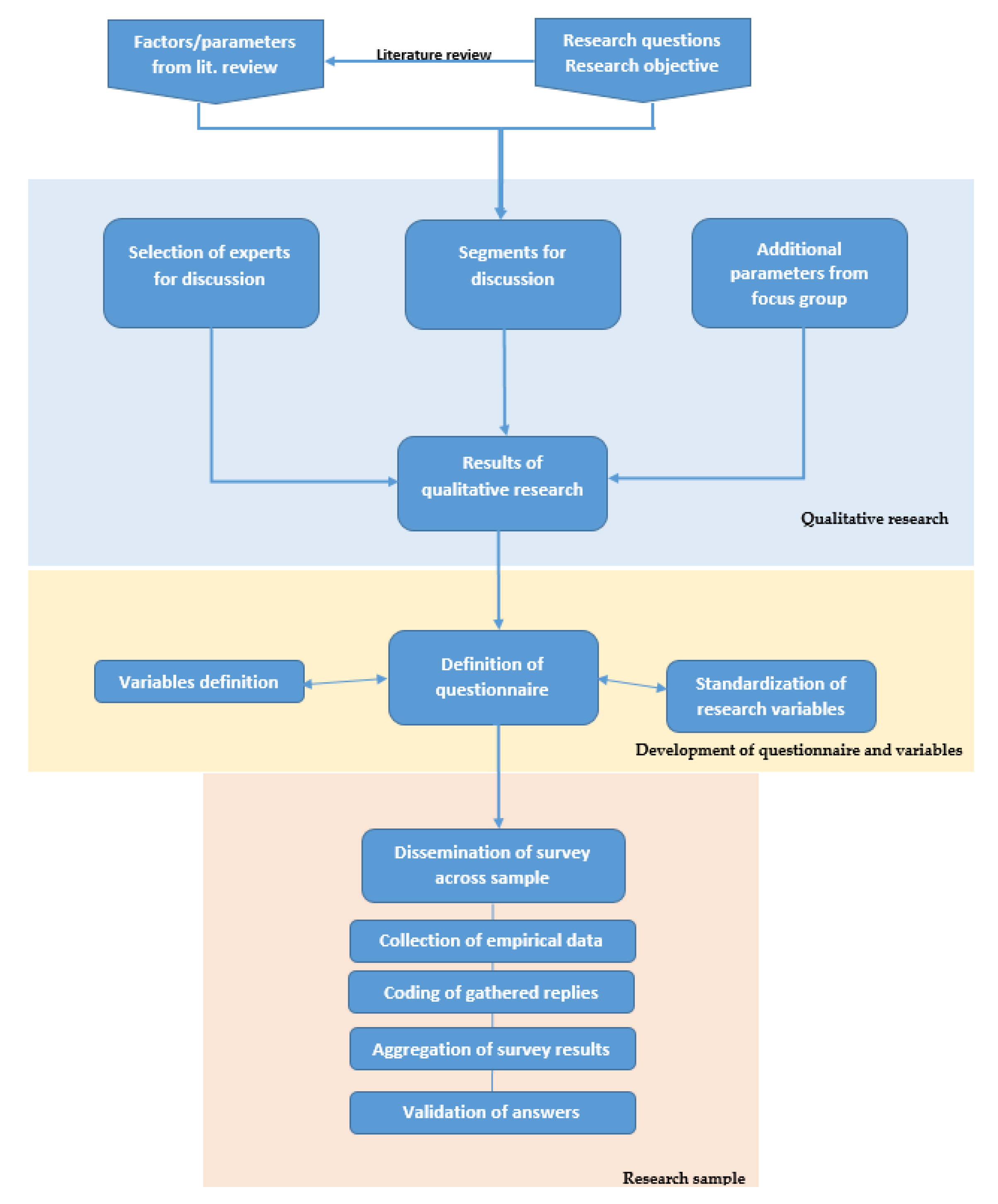

Figure 1 displays all three subsections of this section. Since it was predicted that finding the right approach to this topic and getting the most out of empirical data may represent a crucial effort of this whole research, several steps were made before going into the quantitative part. A logical scheme is displayed in

Figure 1 in order to present the complexity level of conducted steps within the development of research methodology in this manuscript. All authors of this manuscript were highly engaged throughout this process since it ensured that conclusions extracted from the literature review (as well as results from discussion with experts) were channeled all the way through to the quantitative part of the research and discussion afterwards.

Initially, the reader can learn from

Figure 1 about two important facts; the methodology framework and preparation for quantitative research depends on research questions and objectives, as well as from parameters defined after the literature review; and second, the methodology consists of three separate parts, with complex processes within. Qualitative research consists of selection of experts for focus group discussion, the definition of segments for the discussion, and definition of additional parameters after the focus group discussion. Results from qualitative research serve as an input for definition of a research questionnaire, with integral definition of research variables, and standardization of research variables (to prepare processing of survey results in the quantitative part of the research). Finally, the research sample part consists of five consecutive processes, with dissemination of the survey across the sample, to the validation of answers via cross validation tests (by analyzing variability levels within survey results).

Additionally, it must be noted that several outcomes from the implemented research methodology are connected to the research framework, within the quantitative part of this research. These outcomes consist of an initial list of internal and external parameters (business factors), which might influence business performance of an SME, indicators of business performance, as well as collected (and validated) answers from the research sample. Both can contribute to determination of key correlations (with dependent variables), linear regression analysis, and analysis of statistical significance depending on the existence of a certain business factor.

Now follows a presentation of all processes which had to be executed in order to effectively study the main research objective and hypotheses.

3.1. Qualitative Research

As it was previously announced, a small focus group of 10 experts (who cooperate with small and medium sized businesses in Serbia) was organized, to fully understand the circumstances in the Serbian business environment, and to better define research survey questions. Criteria for selection of experts was that they cover various industry sectors, as it can be seen in

Appendix A. The defined goal of focus group discussion was to cross-analyze initial factors from the literature review, with defined main objectives of this research. Discussion time was limited to 3 h.

The results of this proposed discussion determined that the SME business owner is the main pillar of nearly all business and strategic activities, and therefore it can be validated that key impact towards a successful business performance is best understood by SME owners.

The process of qualitative research was organized through the following activities:

• Gathering of contacts and initial inquiry with experts;

• Generating an initial list of parameters from a theoretical review (total of 30 parameters);

• Reduction of dimensions regarding the research problem (from the initial list of parameters, similar ones were joined, and irrelevant parameters were deleted).

In order to operationalize parameters necessary for quantitative part of research (via linear regression analysis) and later testing of research hypotheses (via regression and ANOVA tests), multiple segments of discussion were created, to provide the focus groups a chance to confirm assumptions about relevancy on equal grounds. These are the segments for discussion:

• Entry—parameters that were assessed through literature review, as well as through publicly available databases on the internet;

• Market/Portfolio—parameters about sales share of the SME, form of placement on foreign markets, form of fulfillment of customer needs, all assessed through surveyed SMEs;

• Logistics management—new internal business parameter about ownership over logistics capacities, parameter about number of participated supply chains, and position within a supply chain;

• Indicators of business performance—parameters that were assessed through publicly available databases on the internet;

In addition, the experts were free to suggest their own ideas on parameters that should be analyzed, and that were not part of the theoretical review (conducted prior to this part of the research). New parameters defined by focus group experts are the following:

Main buyers of SME products (local, national, regional, EU/world);

Industry sector of SME;

Type of business (manufacturing, services);

Distinction between SMEs which export to region CEFTA and EU/rest of world.

The authors accepted all of these new parameters, but were only forced to give up on analyzing “industry sector” as a parameter, since there were not enough examples of SMEs from major industry sectors, to proceed on legitimate grounds with this parameter.

Additionally, focus group experts insisted on creating two introductory questions, within inquiry of SMEs candidates for the survey process—whether the SME requires logistics management activities at all, and whether the company is actually an SME, in terms of number of employees (since public data about company size is outdated by a year).

Segments for qualitative research were created to ensure description of internal and external factors of business (determined by literature review), which can be adequately observed by the SME owner, and which can be analyzed accordingly with other parameters.

3.2. Development of Research Questionnaire and Research Variables

The empirical part of the research was conducted with a survey (via questionnaire, available in

Appendix B), on a relatively small sample of SMEs in Serbia. Answers to survey questions were formulated in order to describe the identified gap in existing literature review. Questions focused on the personal perception of the surveyed small or medium sized business owner (or management board member), along with general trends involving SMEs.

After analyzing a list of parameters through discussion, two distinct groups of parameters were determined, and the quantitative part of the research was carried out through them:

• Group of parameters which can be determined by queries on public online databases dealing with Serbian business subjects (such as number of employees, location and owner’s name and surname, financial data);

• Group of parameters attained from the research questionnaire (from SME owners), dealing with market and portfolio characteristics, as well as logistics management of SMEs.

Additionally, considering the second group of parameters, several steps were conducted, towards defining a research questionnaire, in order to carry out the quantitative research via linear regression:

• Definition of survey questions (formulation of possible answers, order between the answers, and number of possible answers on a single question, definition of share/percentage of total);

• Systematization of groups of parameters, by identifying correlations between parameters and survey questions (such as correlations between parameter “Profitability” and survey questions regarding portfolio of the company—about customers, market, and export activities; see

Appendix E for correlations);

• Finalization and elaboration of questionnaire (description of each expected answer and possible implications).

Both groups of parameters that were converted to survey questions, were used in the quantitative part of the research. Certain parameters, which are available to all researchers (without the need to acquire them through a survey), were developed further into independent variables. Additionally, parameters related to calculating indicators of business performance (dependent variables) were obtained from publicly available data within the Serbian Agency of business subjects (SMEs and entrepreneurs). Finally, all possible responses to research questions were converted into independent variables. Relations between all independent variables were set to nominal. After definition of research variables, a standardization of variables was performed (by introducing dummy variables), in order to successfully apply linear regression tests.

Appendix F displays the process of standardization of research variables.

3.3. Research Sample

The survey, related to the operations of small and medium-sized companies was conducted with the support of SME owners and managers from Serbia, over the period from May until July 2019. The total sample in the quantitative survey consisted of 340 companies (response rate is 19%), all originating from Serbia. The survey involved companies employing up to 250 employees from various industry sectors and types of businesses.

The research questionnaire consists of three segments describing the profile of the company. The first part of the questionnaire is dealing with general information about the business, in order to better classify companies. The second part is dealing with the market segmentation profile of the company, and the third is devoted to describing the portfolio of SMEs’ products or services. The last segment is dealing with logistics management of surveyed SMEs. The questionnaire was designed in the form of closed options, where the respondent can choose only one or multiple options. All variables are nominal, and there is no categorical order between responses.

Each respondent had the opportunity to respond by email, by calling (if a telephone number was available), or by using the online questionnaire response form. The questionnaire was sent twice to each company, to ensure that otherwise (very busy) managers and directors were able to find the time to complete the survey questionnaire. The databases of companies used for contacting are very diverse, from the Chamber of Commerce, National Development Agency, organizations focused on working with subjects from Serbian economy, and available online databases.

The results of the survey were matched and aggregated based on the company name, with data publicly available from the Business Registers Agency (company identification number was matched with the company registry provided in the agency database). The validation of the questionnaire was done immediately upon arrival (the email address of the company was checked against the one to which the inquiry was sent), and the identity of the owner was validated. Additionally, it can be stated that all respondents filled in all required answers from the survey, and, therefore, it can be concluded that there was no missing data in survey results. A number of companies was removed from the survey process, who responded to the inquiry stating that their company does not need logistics management in some organized form but operates “only for themselves and their needs”. In addition, some respondents who were contacted reported that the business was in the process of being closed or had already been shut down, so that the interviewing process itself was disabled. Finally, several companies did not have a manager (contact person) available at the time of the survey process, due to over-occupation or absence from the country at the time of contact.

4. Results of Empirical Research

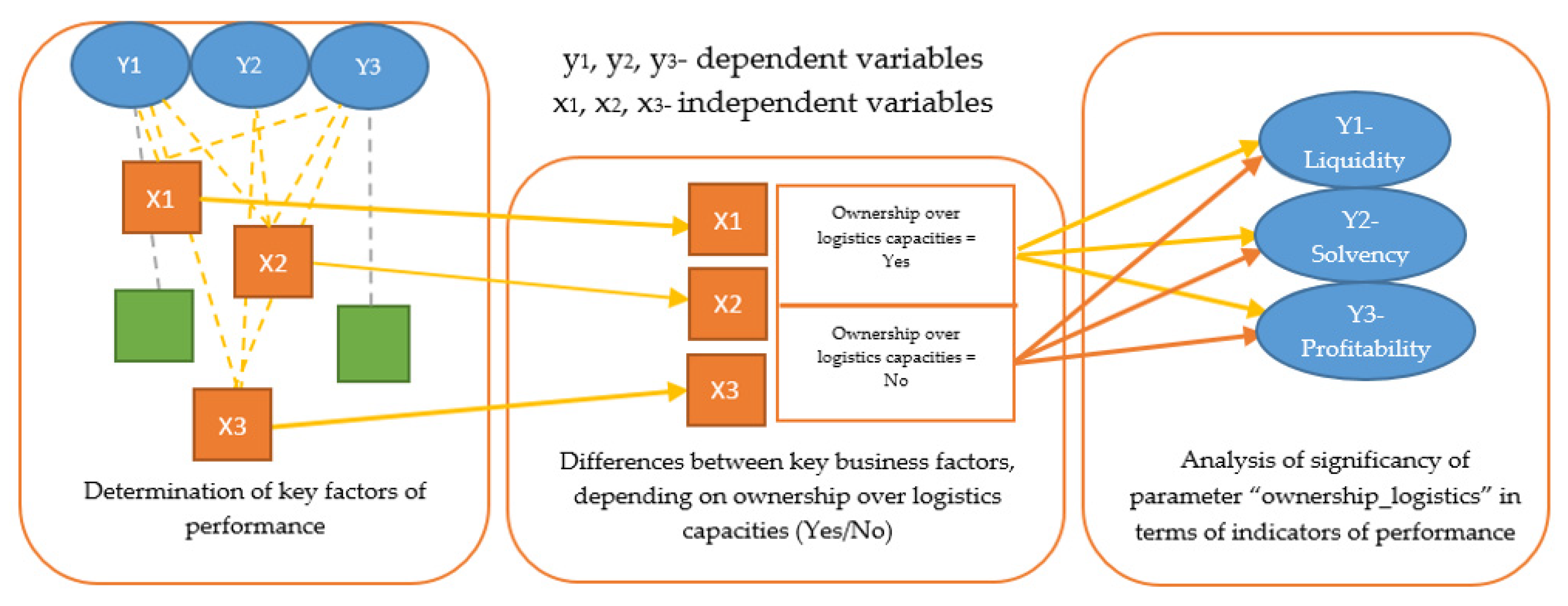

The framework for realization of quantitative research was developed in order to provide answers to the main and auxiliary hypotheses. Therefore, it is necessary to notice three distinct, but connected parts of the framework:

Determination of key influences (factors of business performance, acquired through literature review and surveyed on a sample) on indicators of business performance, measured through linear regression tests;

Analysis of differences relating to determined key business factors, depending on the fact whether the SME owns or leases its logistics capacities;

Analysis of statistically significant differences between and within groups of SMEs in terms of influence of parameter “ownership over logistics capacities”, on indicators of business performance.

In order to provide full transparency of research framework, a detailed graphical overview is introduced with

Figure 2.

Figure 2 displays the flow of research, starting with determination of key correlations between independent variables (x

1, x

2, x

3…, x

n) and dependent variables (y

1, y

2, y

3), and also elimination of low correlated business factors (marked with green) from further analysis. After that, differences between key business factors were determined by analyzing the sample, which was divided by ownership over logistics capacities. Finally, last part consisted of analyzing (statistical significance) whether SMEs in ownership over logistics capacities are more successful (in terms of each indicator of business performance—liquidity, solvency, and profitability) than SMEs that outsource those capacities.

Now follows presentation of characteristics of sampled companies in terms of basic descriptive statistics about the sample.

4.1. Characteristics of Sampled SMEs

On average, sampled companies employed about 48 people (small companies) in 2018, with a clear increase in employment (compared to the previous year) of an average of 3%. Considering the official division of companies by size (less than 10 employees—micro companies; from 10 to 49 employees—small companies; from 50 to 249 employees—medium companies), distribution of surveyed companies is displayed with

Table 1. Other descriptive statistics are displayed in

Appendix C.

The sample does not include companies larger than 249 employees (large companies) but having in mind a one year latency in officially published data, it is possible that a certain percentage of the mid-sized companies grew into large companies in the meantime during 2019.

Within sampled companies based on results from 2018, there was a recorded total of 7128 workers, and in 2017 and 2016 there were 6821 and 6564 employees, respectively, which indicates that employment in small and medium-sized companies in Serbia is increasing on stable grounds. All surveyed companies are limited liability companies, the majority of them manufacturing oriented (60%), as well as service providers (40%).

Representativeness of the sample was secured, in terms of regional and overall economic shares: Belgrade region—160 companies (out of 10,000); Vojvodina region—88 companies (out of 4000); Sumadija and Western Serbia region—42 companies (out of 2000); South and East Serbia region—50 companies (out of 1000). The overall population of SMEs in Serbia is not defined in domestic literature, and there is very little formalized data about SMEs.

All data generated during the survey was processed by using Stata v.15. All sources, references, and sampled data used in this paper were read and analyzed several times; the data was cross-referenced and tested. Internal validity of the data gathered from the sample, was based on the authenticity of survey questions.

4.2. Research Results and Findings

The respondents largely marked local and national level as their main markets of interest, as presented in

Table 2.

When asked about aspects of the market (where they are doing business), the respondents had the opportunity to round off multiple responses, that is, to indicate presence in several different types of markets. They stated that they sell their products and services mainly on the Serbian market (locally or nationally), with a smaller percentage of those exporting to the European Union or worldwide. What is interesting is that there are not enough representatives of companies present in the CEFTA region without being present in the EU, that is, there are more companies that have “skipped” presence in the CEFTA region, having already made a breakthrough in international markets.

For support of the stability of the company’s revenue in the market, there are evidenced results on what constitutes the (major) product or service for the consumer (in terms of sales), where the smallest percentage of companies (20%) stated that they are fulfilling one-off needs for random consumers. The sample is dominated by companies whose portfolio of products or services meets the needs of different (known or random) consumers (55%), while a significant percentage of those companies whose products or services meet the regular, recurring needs of consumers (25%), that is, companies with contract-based work for a larger business entity.

When asked about the fact whether they own or outsource logistics capacities (transport, inventory, distribution), in order to be able to participate in a supply chain, the respondents were divided almost equally (45%—Yes and 55%—No). This fact gives the chance for a proper analysis of this factor, on equal grounds. Additionally, when comparing micro and small versus medium sized businesses in terms of ownership over logistics capacities, there is no significant deviation from overall division, since 60% of micro and small companies versus 41% of medium companies, respectively, are in need of outsourcing logistics capacities.

Owners were invited to determine the share of sales of products/services in relation to the total sales, according to the type of customer (for each type of customer it was possible to choose a share from 0% to 100%). It can be said that most companies (58%) offer products/services primarily for private individuals (domestic or foreign), or for private companies in Serbia (76%). Whereas, a smaller number of companies have a certain share of sales towards state-owned companies in Serbia (18%) or with foreign companies (14%).

From the basic results of the sample, the largest percentage share of sales in companies that meet the predominantly one-off consumer needs is sales to domestic private companies, which is the same in the case of companies that meet predominantly the recurring needs of customers.

In order to identify in which form the surveyed companies distribute their products on the foreign market, all those who have access and need exporting (70% of sample), mostly stated that it was a premium product of small series (45%), while a significant number of companies responded that they exported raw materials to surrounding countries (20%). It is necessary to point out that a significant number of companies reported having no exporting opportunities/needs—up to 30%.

In order to determine the position of the company in the supply chain, the respondents were asked to position their business, and were offered the following answers (they were able to mark multiple options):

• Creating additional value of products/services after purchasing raw materials or semi-finished products from a domestic supplier,

• Creating additional value of products/services after purchasing raw materials or semi-finished products from a foreign supplier,

• Integral creation and distribution of finished products/services, without suppliers,

• Implementation of partnership sales/supply agreements for a larger company (domestic or foreign).

Companies are equally represented in each of identified key positions, with a higher percentage of companies creating value-added products after being purchased from a domestic supplier (40%) or after being imported from a foreign supplier (38%), and only 12% of the companies operate integrally, without the need to participate in a supply chain. It can be concluded that sampled SMEs are mainly positioned within one or more supply chains. When asked about the fact that they operate in one or more supply chains, the owners dominantly (60%) stated that they were involved in only one supply chain (40% of them are involved in two or more).

The

Table 3 below shows the intersection of questions about the number of supply chains and a company’s export products (if exported at all) to foreign markets:

From this simple crosstabulation, two conclusions can be identified:

• Most companies having multiple distribution channels, are exporting premium products,

• Most non-exporting companies participate in only one chain.

Preliminary analyses were conducted using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and it was determined that certain independent variables are in moderate or high correlation with dependent variables (Pearson coefficient larger than 0.3), so it can be concluded that significance level of used parameters is satisfying. Most important correlations can be seen in

Table 4.

From the table it can be concluded that economic sustainability of an SME (all three indicators of business performance) is mostly influenced by whether it exports products/services in the form of large series or participates in multiple supply chains (has options regarding distribution channels). Additionally, liquidity and profitability grow in cases of SMEs doing business with the EU, and profitability grows in cases where SMEs have a portfolio of one time and recurring products/services, or it declines if placement of products is not expanded beyond local regions in the country. Most significant correlations to “Profitability” are in the case of internal business parameters (related to logistics management). Off course, all of these initial correlations must be tested with appropriate tools and techniques. All other determined correlations are presented in

Appendix E.

4.3. Testing of Main Research Hypothesis

Main hypothesis: It is possible to determine key correlations between internal and external factors of a business, which are directly correlated to indicators of business performance of an SME.

Standard linear regression was used to evaluate the ability to successfully and reliably describe the impact of a set of independent variables on three key dependent variables (related to business performance) based on the following parameters:

• demographic characteristics of the organization (type of ownership, type of business (manufacturing, service), number of employees);

• strategic aspects of the business (company portfolio, position in all markets in which the company operates, relationship with suppliers, number of supply chains in which companies participate, ownership over logistics capacities);

• derived indicators of business performance (liquidity, solvency, and profitability) based on recorded data on financial parameters, describing their performance for 2018.

The expediency of the process led to the simple definition of regressions between single pairs (one independent–one dependent variable). The MiniTab statistical tool was used for linear regression analysis. Below are the results of simple regressions, for each independent and dependent variable (one pair indicates one regression). Single regression between dependent variables and independent variables (which do not have established collinearity between themselves, see

Appendix E) was analyzed.

The

Table 5 clearly shows three statistically significant regressions in which the independent variables (all three are internal business factors) have a sufficiently high regression power (according to Adj R

2, with the corresponding

p-value and

t-test values) of the dependent variable “Liquidity”. These variables are: “Creation of value added after purchase from a foreign supplier (import)”, “Export_form_large_series” and “Sales location - EU_rest of world”.

An example of a single regression summary report for the independent variable “Creation of added value after purchase from foreign supplier (import)” in the case of the regression of the dependent variable “Liquidity” is shown in

Appendix D. Having that in mind, now follows an example of linear regression (Equation (1)):

ŷ—Liquidity (based on historic data about financial results)

—Creation of added value after purchase from foreign supplier (import)

Or, if a company creates additional value of products, after importing raw materials from a foreign supplier, its liquidity will be increased by a minimum of 0.54. The regression line confidence interval indicates that (with 95% confidence), so it can be claimed that the regression range of the dependent variable will have an error margin of 2.26. The wider the standard error rate, the greater the bulk of actual data points around the regression line.

The stated weakness of linear regression is compensated for by multiple regression (by introducing additional variables into regression) or by increasing the regression training sample, but the further process of defining a multiple regression analysis (with several independent variables as predictors) was not defined as the goal of this paper.

The following also represents statistically significant regressions for other two dependent variables (solvency and profitability) describing business performance, which are determined over the company’s business data for 2018.

The

Table 6 clearly shows three statistically significant regressions in which the independent variables have a sufficiently high regression power (according to Adj R

2, with the corresponding

p-value and

t-test values) of the dependent variable “Solvency”. These are the variables “Realization of contracts (subcontractor)”, “Sales share-Foreign companies” (both are external business factors) and “Number_of_supply_chains” (internal business factor). Finally, results for third dependent variable “Profitability” are displayed below.

The

Table 7 clearly shows two statistically significant regressions in which the independent variables have a sufficiently high regression power (according to Adj R

2, with the corresponding

p-value and

t-test values) of the dependent variable “Profitability”. These are the internal business factors “Form_of_placement_Portfolio” and “Number_of_supply_chains”.

In order to confirm first hypothesis, it is necessary to analyze the impact of independent variables that characterize a company’s business in the market. The analysis was conducted because of a predefined framework, with the help of several statistical indicators:

The following is

Table 8, that follows the defined framework and function to confirm the first hypothesis, first for the dependent variables describing business performance of an SM—“Liquidity”, as well as for the variables “Solvency” and “Profitability”.

It can also be deduced from the table, regarding the adjusted R2 parameter, as the presented individual regressions explain the variability in the real values of the individual dependent variables, at a very satisfactory average.

This table also clearly suggests that “Liquidity” is mostly under influence of external business parameters, while “Profitability” is dependent of internal business factors. While, “Solvency” records regression from heterogeneous factors, mainly internal but also external ones.

Analyzing the regression coefficients of independent variables, which are a subset of all internal and external factors describing a company’s operations, it can be noticed that none of the presented coefficients are equal to zero (for any dependent variable), which justifies their significance in the analysis of key correlations (in relation to dependent variables liquidity, solvency, and profitability). Additionally, statistical parameters that follow the regression coefficients (p-value and t-test) show that adequate independent variables were used in the analysis (there are no cases where the p-value exceeds 0.05 and the t-test is always at a non-zero level) so it can be concluded that the test results are statistically significant at the 95% level.

Based on all the above, it can be objectively considered that the main hypothesis is fully confirmed, that is, the tested independent variables (which belong to both internal and external factors of business) contribute to the identification of key correlations between internal and external factors of business, which have direct impact on indicators of business performance of an SME. It is legitimate to continue with examination of the auxiliary hypothesis, to determine whether a significant impact exists regarding whether an SME owns logistics capacities over efforts of an SME towards economic sustainability.

4.4. Testing of Auxiliary Hypothesis

Auxiliary hypothesis: There is a statistically significant difference between indicators of business performance of SMEs who own or lease logistics capacities.

In order to confirm/reject the additional hypothesis, it is necessary to analyze the impact of different independent variables within two groups of SME companies, distinguished by the fact that they own or lease their logistics capacities. As a reminder, the financial component of this analysis was found to be expressed through three key dependent variables within individual participants in the chain, so it is legitimate to analyze differences in the values of independent variables for companies within both groups, but also to analyze the statistically significant differences between companies that are in different groups.

Further analysis of variables by defined groups was carried out based on a previously defined framework, but with the help of statistical indicators which are appropriate assumptions, whose accuracy they test. Firstly, an ANOVA test was carried out to determine if there was any statistically significant difference within and between defined groups, and p-value and F statistics were calculated.

The ANOVA test was conducted to compare key indicators of business performance (Profitability, Liquidity, Solvency) of SMEs within and between sampled groups, based on real values for the year 2018, to determine whether this division, according to the fact that the company owns logistics capacities, presents a good model for division at all (confirming this assumption would be a step towards reaching the main objective of the research).

The

Table 9 displays that two groups of companies (within and between groups) are sufficiently representative, when tested for correlations. With the help of the current sample of companies, a great deal of variability was described, within independent variables (based on the values of sum of squares and mean of squares, which are significantly larger than zero). Solvency and Profitability have the highest score for ANOVA (biggest difference of variability, depending on the fact whether an SME owns or outsources logistics capacity). In the case of liquidity, there is not enough difference in variability to be able to confirm that this parameter is under influence of “ownership over logistics capacities”.

Additionally, there is a need to examine variability between key business factors affecting performance of SMEs, divided by the fact regarding whether they own logistics capacities.

Table 10 displays results of ANOVA test within and between groups of SMEs.

From

Table 10, by analyzing level of variability within and between groups, several conclusions can be made. The influence of number of supply chains on solvency and profitability, does not differ significantly if the SME is in ownership over logistics capacities (since for both within and between groups recorded variability is not significant). Additionally, external business factors such as “sales location-EU_world” and “export_form_large_series”, are not influenced by internal factor “ownership over logistics capacities”, regarding liquidity. Finally, all other business factors, “creation of added value after purchase from foreign supplier”, “realization of contracts”, “sales share—foreign companies”, and “form_of_placement_portfolio”, are individually influenced by ownership over logistics capacity (recorded variability within and between groups may potentially state that these business factors have limited influence on business performance, in the case that SME outsources logistics capacity).

Based on all tests and analysis above, it can be objectively considered that the auxiliary hypothesis is confirmed, that is, the tested independent variables confirm that there is a statistically significant correlation of indicators of business performance “Solvency” and “Profitability” and performance between companies who own logistic capacities or outsource them. That is, it can be defined with 95% certainty (measured on sampled SMEs) that one of the key preconditions for economic sustainability of a company within a supply chain lies in the fact whether it owns logistics capacities.

Undoubtedly, after analyzing all test results, it can be concluded that there is a significant relationship between variables (adjusted R2 is very close to “1”, F statistics value is much larger than “1”, RSE is slightly above standard deviation level, p-value is smaller than 0.05) and it can be concluded that the auxiliary hypothesis is confirmed. All tests were conducted on predefined values within the experimental region (based on values of variables within the sample).

4.5. Validation of Research Results

One important step after testing of both hypotheses, is presenting the validation of research results according to the research questionnaire, which was conducted with a cross validation test. Having in mind a relatively small sample, with significant complexity (number of dimensions), we decided to use the “Leave one out cross validation” test (LOOCV), by analyzing the variability (following mean squared error—MSE) in estimating F statistics and adjusted R

2. It was important to avoid bias in estimation of the mean squared error, since it was necessary to achieve a satisfactory level of variability across the sample (by measuring variability between answers on research questions). Below Equation (2) is presented, defined by James [

49] for performing a cross validation test, and afterwards a single graphical display of LOOCV tests (

Figure 3), on a sample of 340 SMEs (one line represents several SMEs with similar values of MSE or Adjusted R

2/Fstat).

There exists a sufficient level of variability across the sample, measured through F statistics and adjusted R2. The LOOCV performed ensures that answers from sampled SMEs are statistically significant, and it is safe to claim that there is no bias under which the owners formed their responses, which would effectively cause false argumentation and empirically unsupported conclusions.

5. Discussion

The authors of this paper assert that there is an evident necessity to develop a better and more comprehensible understanding of the moderating role of different influences on economic sustainability of an SME. This research found evidence for existing correlations between internal and external factors of businesses and business performance of SMEs. From

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, it was possible to conclude the following:

regarding “Liquidity” (

Table 5)—all three slopes for these parameters are positive, which means that a company will have a higher ratio of liquidity, if it exports a large series of products, with at least a portion of it to the EU (or rest of world), and is involved in a supply chain with a foreign supplier (external business factors),

regarding “Solvency” (

Table 6)—all three slopes for these parameters are positive, which signifies that a company participating in multiple supply chains will also have higher ratio of solvency, if it sells products mainly to foreign companies, with the form of subcontracting for a larger entity,

regarding “Profitability” (

Table 7)—a direct influence on higher profitability is achieved through participation of an SME in multiple supply chains, and by placing products in the form of a portfolio (multiple one-time and recurring products), and diversifying sources of profit in that way (internal business factors).

This can present itself as a useful regression finding, having in mind the perception of owners/managers, directly focused on business outcome of most of their efforts in a business surrounding.

One of important external factors discovered in this research is “form of exporting products”, since internationalization efforts can represent am appropriate driver of a sustainable SME, regarding business performance. Since Serbia is a country recording evident economic development over the past five years, it was also necessary to cross-examine these claims with studies from other, more developed markets from Europe. Naldi [

54] discovered in a study of Swedish SMEs that internationalization promotes knowledge acquisition from new markets, which can produce economic growth of SMEs, while Kuivalainen [

55] found in a research on Finnish SMEs that in the case of small (medium) companies, a higher level of internationalization produces better sales performance and higher profitability, while large companies record higher profitability and market diversification. It can be concluded that internationalization as a driver of profitability growth, is not a mere consequence of rapid economic development and market expansion of countries such as Serbia.

In addition, the claimed relation between internationalization and profitability growth is in accordance with a previous study by Zhou [

56], who discovered that SMEs which utilized export of their products, register immediate profitability growth, as well as decrease of competition level intensity. The later could not be examined within this research paper.

Findings from this research expand on previous work from Burlea and Mihai [

44], since it provides a complementary analysis of influences to business profitability. This study was a pioneer in segmentation of sales by location and by type of customer, determining key differences between SMEs who distribute their products locally and only to domestic consumers (or companies), and SMEs which are present on an international stage and have a very diversified consumer base. This study can be a useful addition to a previous study by Deng [

57], who outlined e-commerce channels as a form of market breakthrough for SMEs which are not present in foreign markets with their products. On the other side, Karamehmedovic and Bredmar [

58] discovered that customer loyalty and satisfaction are primarily leading to higher profitability, with no significant difference between sales channels.

One of key conclusions of this research lies in the fact that ownership over logistics capacities presents an internal business factor which aids in achieving more sustainable results of business, in terms of solvency and profitability. This research can present itself as an expansion on Urzua- Morales [

59] who analyzed costs of externalities, thus also affecting increased solvency of a business. Logistics capacity in both papers is approached as a factor of influence on business outcome.

These important findings can help expand initial conclusions by Kerbach and Mocan [

60] and Bannon [

61], all of whom have analyzed supply chain management of SMEs in different environments. This cross-analysis with other similar papers, as well as critical approach to research results, provides very fruitful insights into SME owners/managers trying to identify and control critical sustainability aspects of economic practice outside corporate environments.

6. Conclusions

Based on everything that was analyzed, in order to comprehensively understand the problem, existing concepts are now expanded with the following conclusions and directions:

• A statistically significant correlation can be found in analyzing business performance between companies which possess logistical capacities of their own, and those who do not;

Efforts towards economic sustainability are more successful in SMEs who are in ownership over logistics capacities (measured mostly through indicators of business performance);

• The key external aspects and internal aspects of the business that affect the key business performance of the company are defined—outlining exports of large series (mainly to foreign companies—B2B sales), collaboration with foreign suppliers, as main external factors, and participation in multiple supply chains, and diversification of sales portfolio (multiple one time and recurring products or services) as main internal factors;

• There is no statistically significant difference in business performance between companies participating in one or more supply chains, with very few companies participating in only one chain (such companies often fall into problems when the supply chain collapses).

This research helps in partial closing of the research gap regarding impact of logistics capacities on economic sustainability of companies. Some similar attempts concerning this topic were previously made by Zimon and Zimon [

62], regarding the influence of logistics on profitability, as well as by Green [

63], with a study of logistics performance and its impact on marketing and financial performance. This research expands on these studies, by focusing on eight key business factors in the SME environment, such as position within a supply chain, export location and form, sales share, and number of supply chains.

The main limitation of the research was the possibility to get answers from the required number of companies for statistically significant correlations between various influences on indicators of business performance. Finally, it is necessary to bear in mind that this study only initiates further efforts towards understanding how logistics capacity can drive SMEs towards better results on the market (domestic and foreign) in terms of economic sustainability, which then fosters all other types of sustainability—social, environmental, etc.

Practical Implications and Future Research

Efforts towards generalization of research results can be directed in two ways—by analyzing the narrowing of the research gap regarding influence of ownership over logistics capacity on business success, and by positioning this newly determined factor of business in real life business practice.

This research study contributes to existing literature by determining “the ownership over logistics capacities”, as another business factor with clear potential to influence business success of an SME. The biggest influence of the parameter “ownership over logistics capacities” was detected with solvency and profitability, since analyzing liquidity did not result in a large difference of variability (ANOVA test within and between groups). Therefore, in terms of solvency, companies in possession of internal and external logistics capacities are more economically sustainable in the long term, since they are in a position to diversify their customer base, and are not directly influenced by other participants in the supply chain (with reduced risk of failing because of problems within the supply chain). In terms of empirical context of the conducted research, it must be expressed that ownership over logistics capacity cannot influence indicators of business success directly, but only within an integrated effort of managing other factors of business performance, such as market and portfolio based activities, internationalization efforts, or logistics and supply chain management activities. This paper can support those efforts by offering findings regarding key internal and external factors of businesses influencing key indicators of business performance. Additionally, these factors were analyzed separately by the fact that whether an SME outsources logistics capacities, it can damage the influence of other factors on key indicators of success, factors coming mainly from the logistics sphere of business (“creation of added value after purchase from foreign supplier”, “realization of contracts”, “sales share-foreign companies”, and “form_of_placement_portfolio”).

When it comes to profitability, SMEs are in position to plan their future assets with more predictability, and therefore achieve higher margins of profit, because of being able to deliver/distribute products autonomously, or with very limited support. Meanwhile, since this cannot be objectively recorded in case of a country outside EU financial control regulations, the true impact of the new factor of business performance is still not fully clear.

Future lines of research can be diversified towards two subtopics regarding logistics management of SMEs involved in a supply chain. The first path of diversification follows the study of Hong and Jeong [

64], and it includes the comparison of SMEs with large companies (who are also participating in supply chains), in terms of key business factors and their impact on economic sustainability. It would be interesting to see whether SMEs are striving to preserve their status of “not being large”, to be able to apply for grants, and how this fact can influence their sustainability on the long run. The second path can follow on previous efforts made by Stoian [

65], dealing with internationalization efforts of SMEs, following continual efforts of small and medium sized businesses towards economic sustainability. In this case, there must be made a clear distinction with regional expansion of an SME, and expansion on a larger scale (whole EU market or world).