Promoting Disaster Resilience: Operation Mechanisms and Self-Organizing Processes of Crowdsourcing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Application of Crowdsourcing in Disaster Governance

2.2. Disaster Resilience

2.3. Complex Adaptive System (CAS) Conceptual Framework

3. Method

4. Results

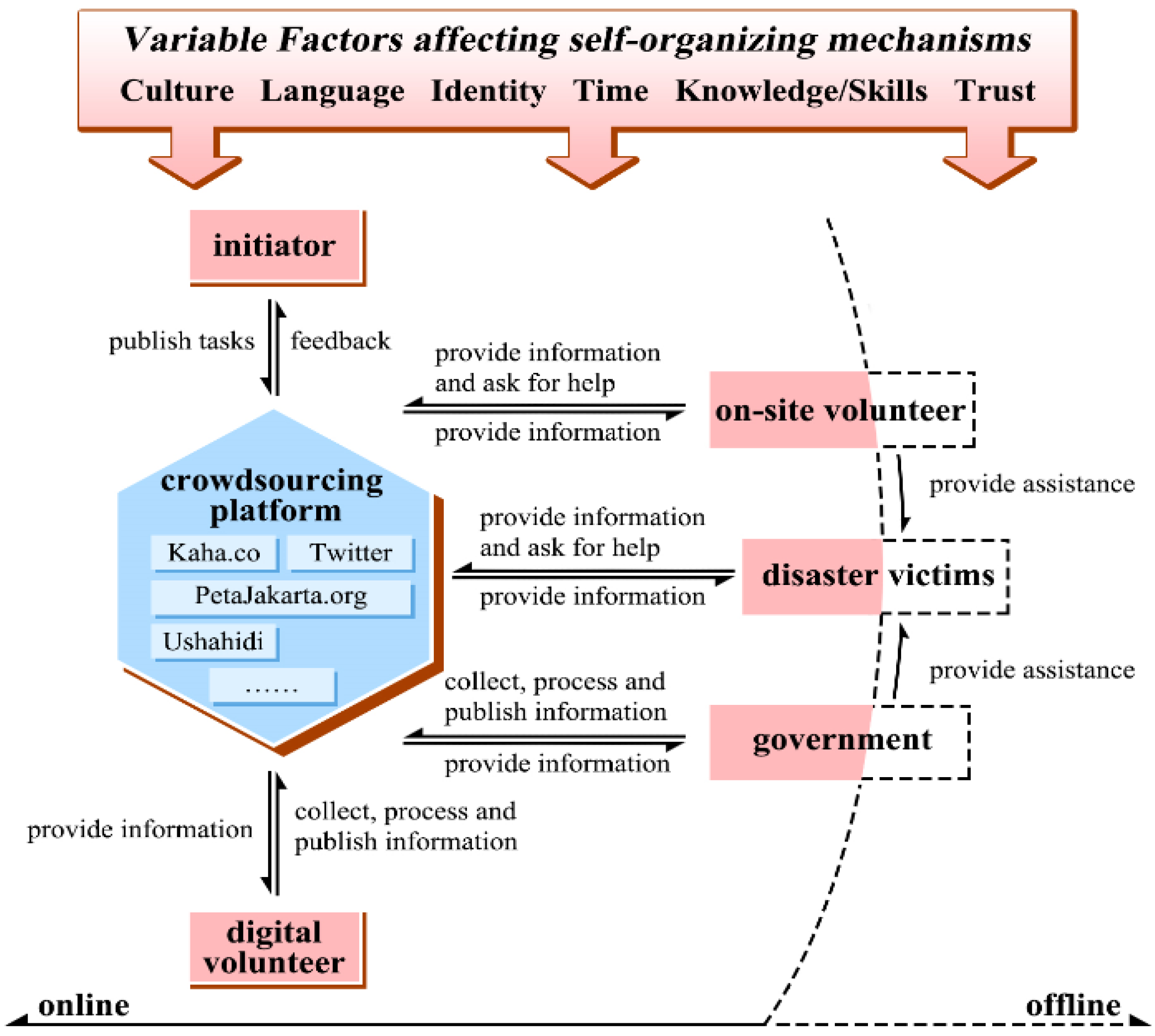

4.1. Self-Organizing Operation Mechanisms of Crowdsourcing in the Disaster Context

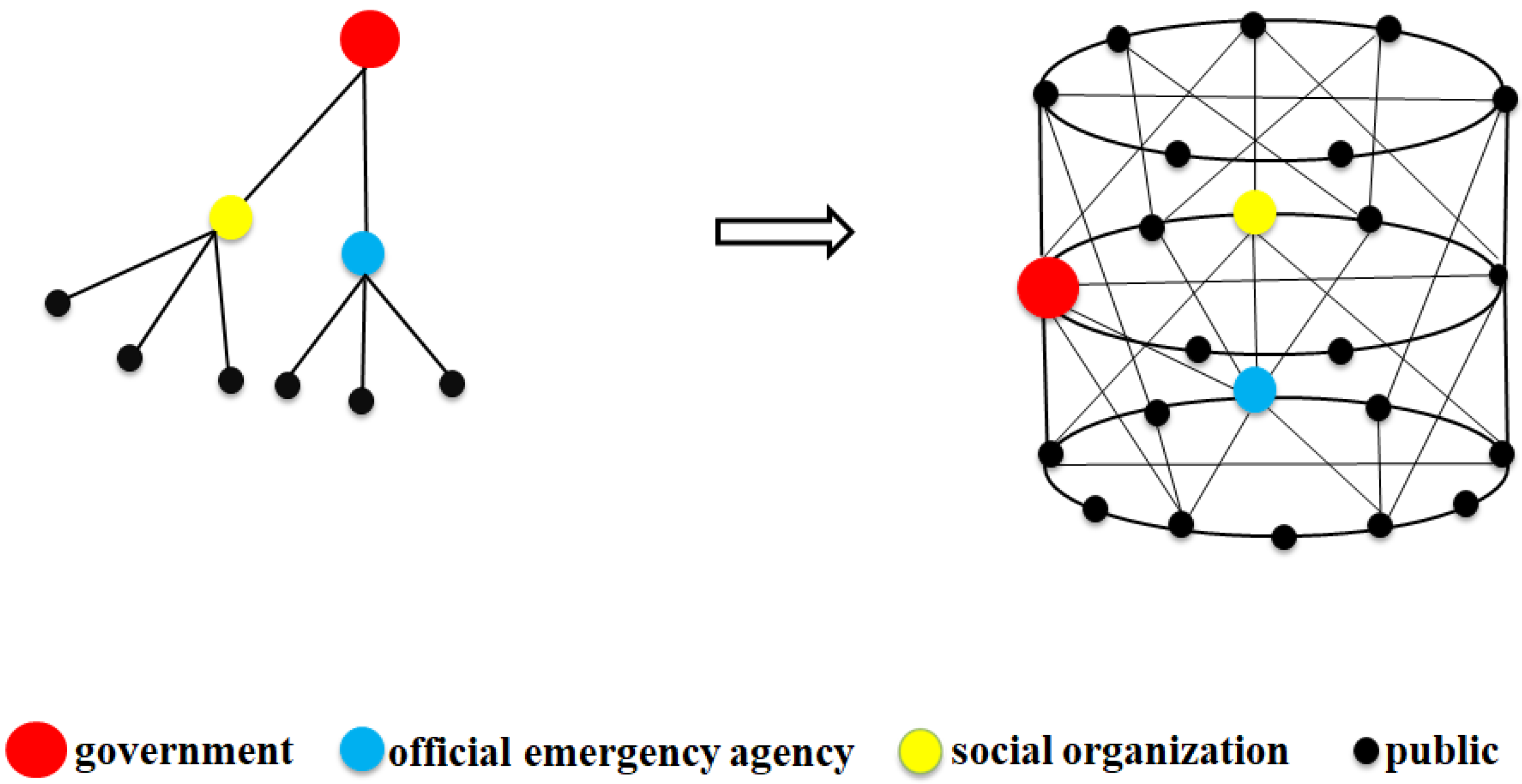

4.2. Crowdsourcing Structure and Self-Organizing Processes

4.2.1. Strengthen Communication and Coordination

4.2.2. Optimize Emergency Decision-Making

4.2.3. Improve the Ability to Learn and Adapt

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comfort, L.K. Self-organization in complex systems. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 1994, 4, 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Estellés-Arolas, E.; González-Ladrón-De-Guevara, F. Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition. J. Inf. Sci. 2012, 38, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, K.B.; Springgate, B.F.; Lizaola, E.; Jones, F.; Plough, A. Community engagement in disaster preparedness and recovery: A tale of two cities—Los Angeles and New Orleans. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2013, 36, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baybay, C.S.; Hindmarsh, R. Resilience in the Philippines through effective community engagement. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2018, 34, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, A.; Verevkin, A. Digitalization and Evolution of Civic Engagement: New Ways of Participation in Public Policy, International Conference on Digital Transformation Global Society; Springer International Publishing: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kongthon, A.; Haruechaiyasak, C.; Pailai, J.; Kongyoung, S. The role of social media during a natural disaster: A case study of the 2011 Thai Flood. Int. J. Inn. Tec. Manag. 2014, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougal, K. Using Volunteered Information to Map the Queensland Floods. Available online: https://eprints.usq.edu.au/20272/5/McDougall_SSSC2011_PV.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Chatfield, A.T.; Brajawidagda, U. Crowdsourcing hazardous weather reports from citizens via twittersphere under the short warning lead times of EF5 intensity tornado conditions. In Proceedings of the 47th International Conference on System Science, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2014; pp. 2231–2241. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, J. The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Mag. 2006, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Degrossi, L.C. Flood Citizen Observatory: A Crowdsourcing-Based Approach for Flood Risk Management in Brazil. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262939561_Flood_Citizen_Observatory_a_crowdsourcing-based_approach_for_flood_risk_management_in_Brazil (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Chu, E.T.; Chen, Y.L.; Lin, J.Y.; Liu, J.W.S. Crowdsourcing support system for disaster surveillance and response. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications, Taipei, Taiwan, 24–27 September 2012; IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann, J.; Limbu, M.; Wang, D.; Kauppinen, T. Crowdsourcing Linked Open Data for Disaster Management. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.232.1448&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=19 (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- Schulz, A.; Paulheim, H.; Probst, F. Crisis information management in the Web 3.0 age. In Proceedings of the 9th International ISCRAM Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–15 April 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.; Palen, L. Twitter adoption and use in mass convergence and emergency events. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2009, 6, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejri, O.; Menoni, S.; Matias, K.; Aminoltaheri, N. Crisis information to support spatial planning in post disaster recovery. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Liu, R. Feasibility study of using crowdsourcing to identify critical affected areas for rapid damage assessment: Hurricane Matthew case study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.; Winterfeldt, D.V. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra. 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, D.; Frank, K.; Robertson, P.; Lichtenstern, M. Providing real-time assistance in disaster relief by leveraging crowdsourcing power. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careem, M.; Silva, C.D.; Silva, R.D.; Raschidt, L.; Weerawarana, S. Sahana: Overview of a disaster management system. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Information and Automation, Qingdao, China, 15–17 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Barbier, G.; Liu, H. Promoting coordination for disaster relief—from crowdsourcing to coordination. In Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction. SBP 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Salerno, J., Yang, S.J., Nau, D., Chai, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Volume 6589, pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, T.; Kotthaus, C.; Reuter, C.; Dongen, S.; Pipek, V. Situated crowdsourcing during disasters: Managing the tasks of spontaneous volunteers through public displays. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2017, 102, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freifeld, C.C.; Chunara, R.; Mekaru, S.R.; Chan, E.H.; Kass-Hout, T.; Iacucci, A.A.; Brownstein, J.S. Participatory epidemiology: Use of mobile phones for community-based health reporting. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryvasheyeu, Y.; Chen, H.; Obradovich, N.; Moro, E.; Hentenryck, P.V.; Fowler, J.; Cebrian, M. Rapid assessment of disaster damage using social media activity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paton, D.; Millar, M.; Johnston, D. Community resilience to volcanic hazard consequences. Nat. Hazards 2001, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, P. Vulnerability, Resilience and the Collapse of Society: A Review of Models and Possible Climatic Applications; Canada University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1981; pp. 124–186. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D.; Johnston, D.; Smith, L. Responding to resilience and adjustment adoption. Aust. Manag. 2001, 16, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 508–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, E.; Buckle, P. Developing community resilience as a foundation for effective disaster recovery. Austra. J. Emerg. Manag. 2004, 19, 324–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.; Pfefferbaum, R. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, M.; Mckee, M.; Murray, V.; Leonardi, G. Resilience thinking in health protection. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B. The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 2006, 30, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, C.; Van Niekerk, D.; Raju, E. Disaster resilience and complex adaptive systems theory: Finding common grounds for risk reduction. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2016, 25, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity; Leonardo, Addison-Wesley, Reading Mass: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 114–216. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, L.K. Coordination in rapidly evolving disaster response systems: The role of information. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 48, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbasat, I.; Goldstein, D.K. The case research strategy in studies of information systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Cable, D.M.; Sherman, J.W. How passive ‘face time’ affects perceptions of employees: Evidence of spontaneous trait inference. Soc. Sci. Elec. Pub. 2010, 63, 735–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Acade. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 543–576. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlbacher, F. The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study Research; Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vienna, Austria, 2005; Volume 7, Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0601211.www.qualitative-research.net (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Peng, L. Crisis crowdsourcing and China’s civic participation in disaster response: Evidence from earthquake relief. China Inf. 2017, 31, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.B. Crisis crowdsourcing framework: Designing strategic configurations of crowdsourcing for the emergency management domain. Comp. Sup. Coop. Work. 2014, 23, 389–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P. Crisis mapping in action: How open source software and global volunteer networks are changing the world, one map at a time. J. Map Geogr. Libr. 2012, 8, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Johnston, E.W. A framework for analyzing digital volunteer contributions in emergent crisis response efforts. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 1308–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Glennon, A.J. Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: A research frontier. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2010, 3, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogie, R.I.; Clarke, R.J.; Forehead, H.; Perez, P. Crowdsourced social media data for disaster management: Lessons from the PetaJakarta.org project. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 3, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.M.; Chan, E.; Hyder, A.A. Web 2.0 and internet social networking: A new tool for disaster management?—Lessons from Taiwan. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak 2010, 10, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby-Arnold, S.; Brockdorff, N.; Fallou, L.; Bossu, R. Truth, trust, and civic duty: Cultural factors in citizens’ perceptions of mobile phone apps and social media in disasters. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2019, 27, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbird, K.; Palen, L. “Voluntweeters” self-organizing by digital volunteers in times of crisis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1071–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, L.K. Crisis management in hindsight: Cognition, communication, coordination, and control. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 67, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart-Gansiniec, R.; Sułkowski, Ł. Crowdsourcing—A New Paradigm of Organizational Learning of Public Organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, L.K.; Zhang, H. Operational networks: Adaptation to extreme events in China. Risk Anal. 2020. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/hVXlYD_4lc-O1xQxBWOiTA (accessed on 20 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sukhwani, V.; Shaw, R. Operationalizing crowdsourcing through mobile applications for disaster management in India. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Event | The Application of Crowdsourcing |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake [40] | The ‘Home of the volunteers’ group on QQ (a Chinese commercial instant messaging service), gathered more than 200 active volunteers, who coordinated more than a third of the provincial Sichuan civil organizations to participate in disaster relief operations. The Douban (a social networking site) volunteer team collected disaster information on relief needs from across the internet, using sources such as blogs, local radio station websites, and QQ groups of rescue workers and rescue organizations. The processed information was classified with symbols, to portray the information visually on the crisis map. |

| 2 | China 2010 Yushu Earthquake [40] | The Huaxia Commonwealth Service Centre (a coalition of NGOs) set up a special forum on their website to release information about the disaster and to coordinate and organize members, other social groups and individual volunteers to participate in disaster relief. The released information was predominantly collected through two social networks: the Blue Sky Rescue (an alliance of civic outdoor rescue teams), and a network alumni association composed of students and white-collar professionals from the Qinghai Province. |

| 3 | Republic of Haiti 2010 Haiti Earthquake [41] | The public sent text messages, emails, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media about stranded people, medical conditions, tents, and food needs to Ushahidi (a crowdsourcing platform for social activism and public accountability). This information was verified, processed and mapped by remote digital volunteers. The Open Street Map (OSM), an open-source mapping project, was used by international digital volunteers to create a more accurate map of Haiti. Finally, victims sent free ‘help-wanted’ messages to the text hotline Mission4636, which were translated, processed and forwarded to relief organizations by digital volunteers. |

| 4 | Japan 2011 East Japan Earthquake [42] | Japanese OSM volunteers closely monitored Twitter to collect, analyze and map crisis-related data to Sinsai.info (a crisis-mapping site that uses the Ushahidi platform). This provided comprehensive and timely information on the scope of the disaster and the resulting relief needs. |

| 5 | Nepal 2015 Nepal Earthquake [43] | Nepalese expatriates and local volunteers developed a crowdsourcing platform called kaha.co, which allowed those in need to easily reach out to those who were donating support. The platform allowed people to fill out forms to request help, and the local public and aid organizations to post about donated resources and services that they could provide. |

| 6 | USA 2009 Wildfire in Southern California [44] | Volunteers created a crisis map site that synthesizes various online sources such as tweets, MODIS images (high temporal resolution images that allow tracking of changes in the landscape over time), and news reports. Volunteers continuously updated the ‘fire range’ that was used in official reports. The crisis map also provided important information about the location of the fire, the evacuation order, and the emergency shelter location. |

| 7 | Russia 2010 Russian forest fires [42] | Bloggers crowdsourced information from disaster sites to create crisis maps that showed where the fire had broken out, and also the water, food, medical care and other information needed for local relief efforts, turning the platform into a ‘help map’. |

| 8 | Indonesia (3 flood seasons between 2013–2016) Flood in Jakarta [45] | The PetaJakarta.org system was deployed to aggregate the locations and conditions of local flood events reported by the public via social media and to generate an open real-time map of the city’s flood situation. |

| 9 | Thailand 2011 Thailand Flood [6] | The public uses Twitter to disseminate and obtain information about flood hazards, including timely situational information, early warning forecasts, support notices, and resource requests. More influential Twitter users include disaster-related government agencies and NGOs, and people can choose the source of information they will track during a disaster in order to obtain timely and credible information. |

| 10 | Australia 2011 Queensland Flood [7] | The Australian Broadcasting Corporation released the Queensland Flood Crisis Map where people can send GIS-related photos and videos via email, SMS, Twitter or the platform itself. By combining this information with existing geographic information, hydrological data, and local knowledge, organizations can reconstruct flood areas to map the scope of the flood. |

| 11 | USA 2013 An EF5 tornado (highest level tornado on the Fujita scale) in Moore, Oklahoma [8] | NWS Norman (the largest regional office of the US National Weather Service) runs an experimental Twitter account @NWS Norman. NWS Norman introduced a specific topic tag on Twitter to facilitate citizens and tornado observers to submit their dangerous weather reports and geotagged hail and tornado photos. |

| 12 | Taiwan 2009 Typhoon Morakot [46] | A group of netizens from the Taiwan Digital Culture Association set up an unofficial Morak network disaster reporting center, which reported current losses and demand in the storm-affected areas and nearby areas. Subsequently, the website was integrated and updated with the official disaster relief center. The website is combined with Google Maps, and residents waiting for rescue can post information such as the current location and the latest damage caused by severe rainfall and landslides on the map. |

| Type | Actors | Responsibilities | Tasks undertaken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiator | Government, NGO, business, individual |

|

|

| Contractor | On-site volunteers: any person present at the disaster scene; could be Government, NGO, business, individual members of the public |

|

|

| Digital volunteers: come from all over the world and have different knowledge backgrounds, use crowdsourcing platforms to help with disaster actions |

|

| |

| Disaster victims: direct victims of the disaster |

|

| |

| Government: government employees |

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Z.; Zhang, H.; Dolan, C. Promoting Disaster Resilience: Operation Mechanisms and Self-Organizing Processes of Crowdsourcing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051862

Song Z, Zhang H, Dolan C. Promoting Disaster Resilience: Operation Mechanisms and Self-Organizing Processes of Crowdsourcing. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051862

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Zhijun, Hui Zhang, and Chris Dolan. 2020. "Promoting Disaster Resilience: Operation Mechanisms and Self-Organizing Processes of Crowdsourcing" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051862

APA StyleSong, Z., Zhang, H., & Dolan, C. (2020). Promoting Disaster Resilience: Operation Mechanisms and Self-Organizing Processes of Crowdsourcing. Sustainability, 12(5), 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051862