The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emotional Intelligence

- (1)

- The self-emotions appraisal (SEA): This dimension reflects the ability of a person to understand his/her own emotions and be able to express them properly, then apply the knowledge of those emotions to create beneficial outcomes.

- (2)

- The other emotions appraisal (OEA): This component assesses the ability of an individual to observe and understand other’s emotions. A person who has high capability in this dimension will be able to observe other people’s emotions and predict other’s emotional reactions;

- (3)

- The use of emotion (UOE): This aspect evaluates the ability of an individual to access, generate and use his/her emotions to facilitate personal performance. People who rate highly in this ability will be able to return rapidly to normal psychological states after suffering depression or feeling upset;

- (4)

- The regulation of emotion (ROE): This dimension mentions the ability of an individual to regulate his/her emotions to achieve an expected outcome and be able to remain balanced from psychological distress to solve problems.

2.2. Turnover Intention

2.3. Work-Family Conflict

2.4. Job Burnout

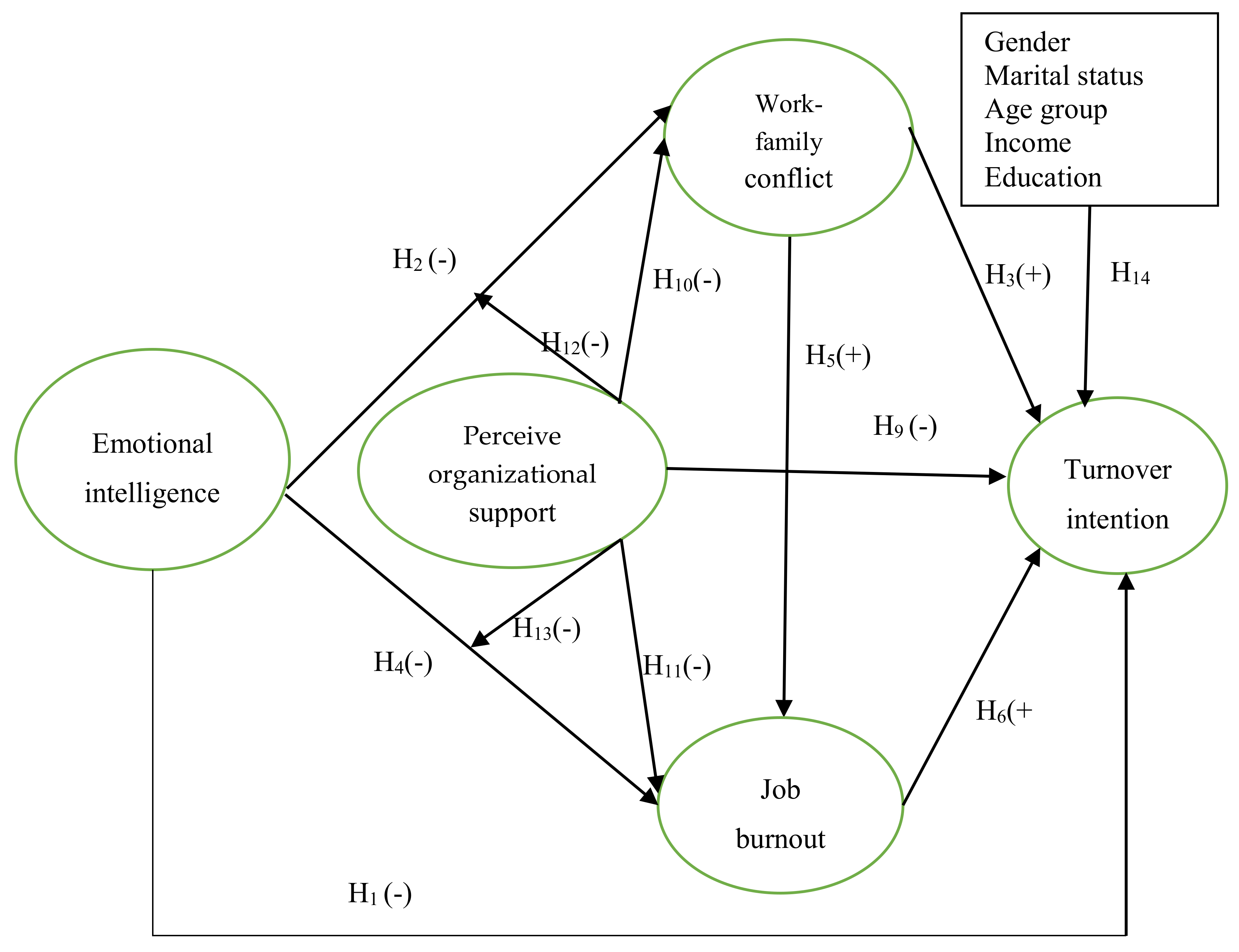

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Emotional Intelligence and Turnover Intention

3.2. Emotional Intelligence and Work-Family Conflict

3.3. Work-Family Conflict and Turnover Intention

3.4. Emotional Intelligence and Job Burnout

3.5. Work-Family Conflict and Job Burnout

3.6. Job Burnout and Turnover Intention

3.7. The Mediating Role of Work-Family Conflict and Job Burnout

3.8. Perceived Organizational Support

3.9. Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

3.10. Control Variables

4. Research Methodology.

4.1. Procedure and Sampling Size

4.2. Measurement

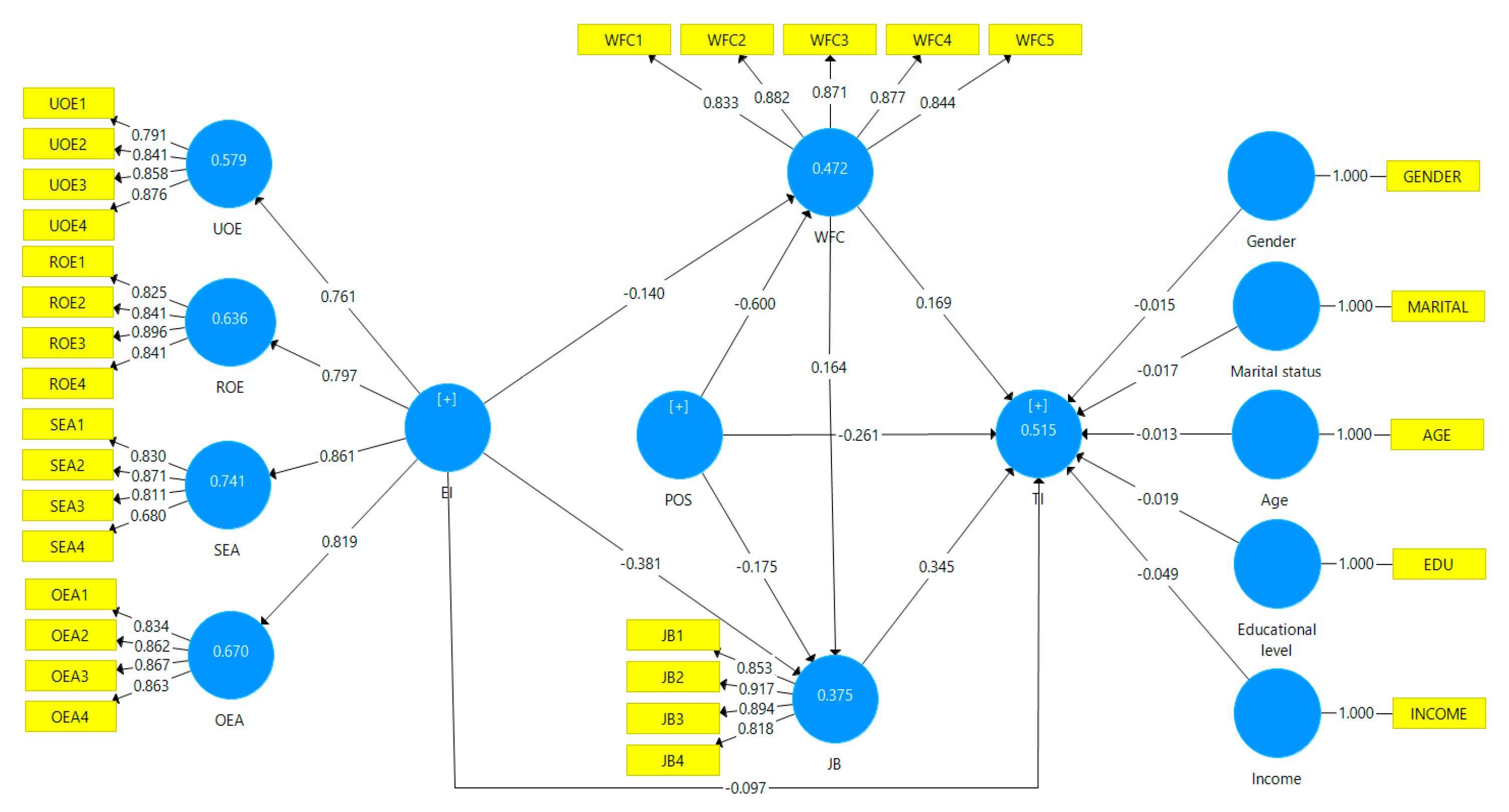

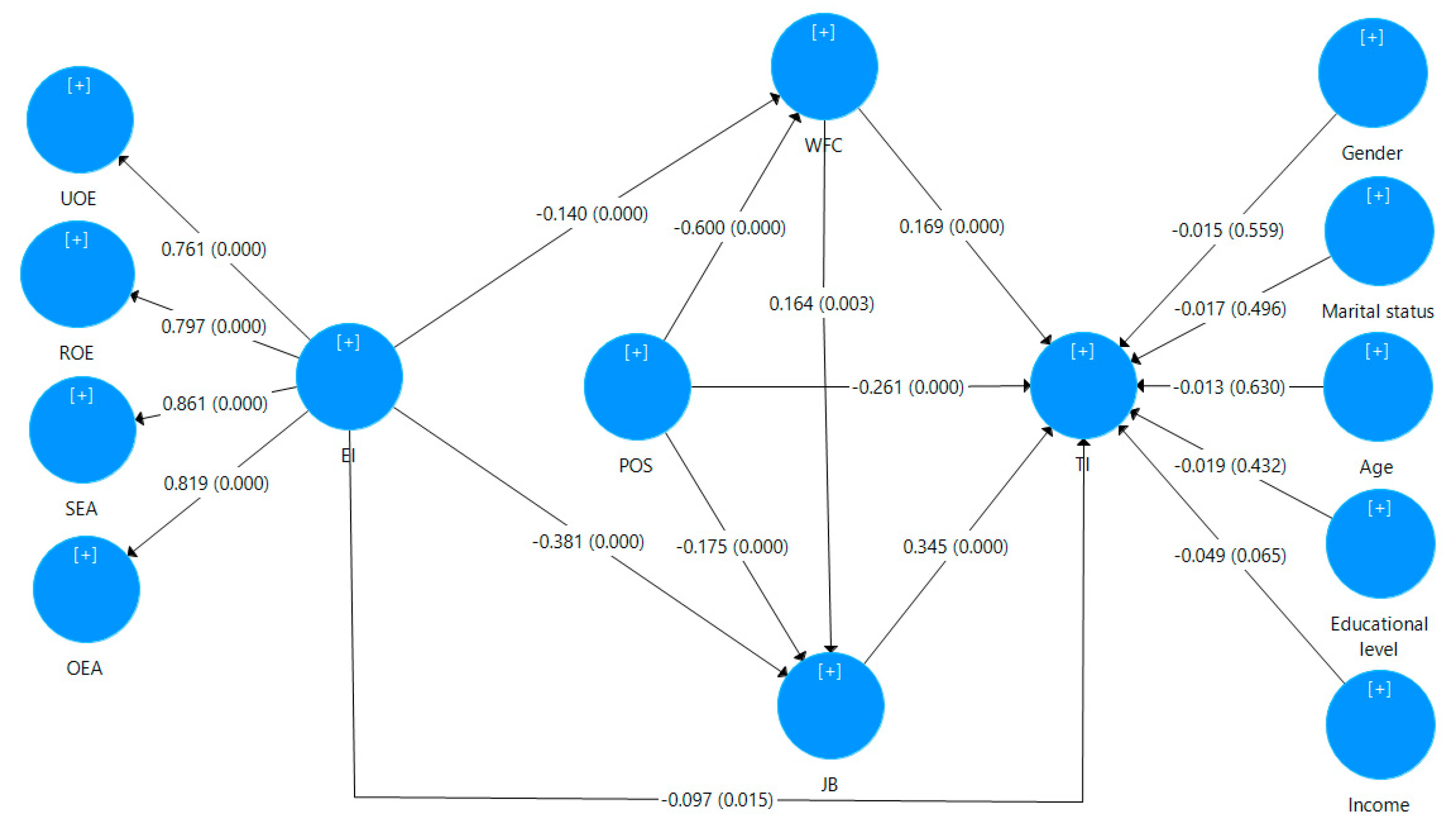

4.3. Partial Least Squares Regression

5. Research Results

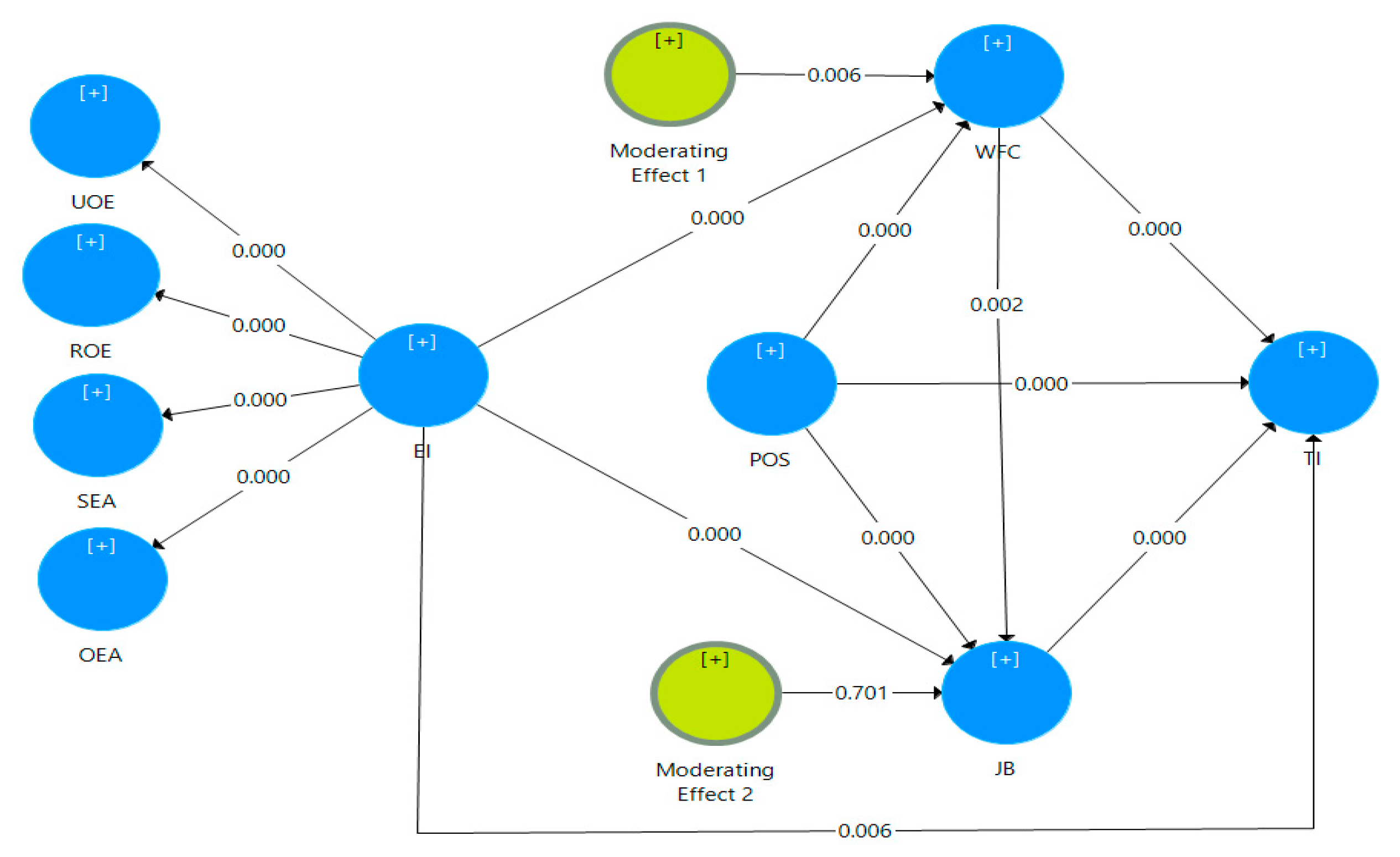

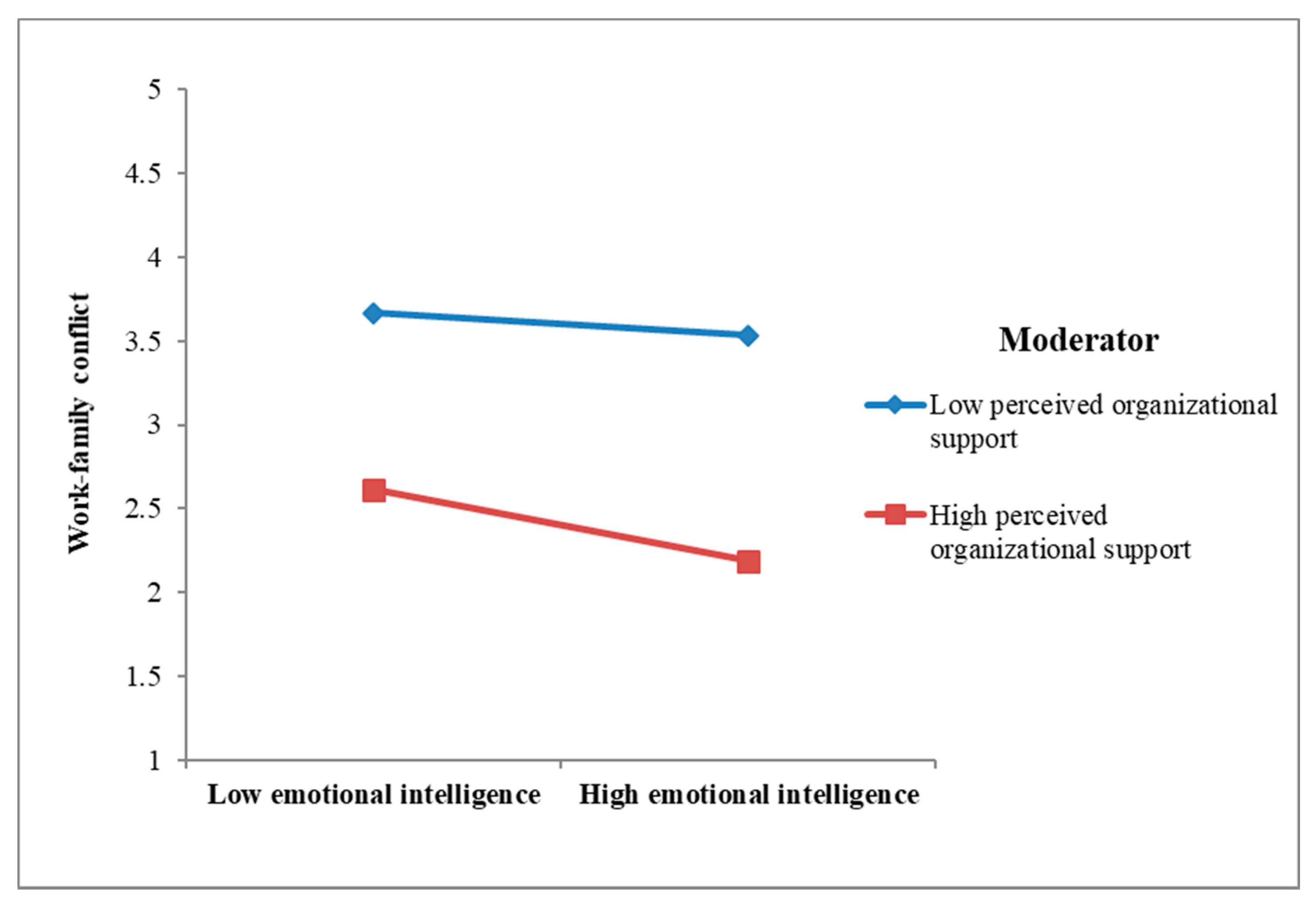

5.1. The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

5.2. Model Fit

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Managerial Implications

9. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, G.; Chen, J.; Lu, Q. The relationship between workplace violence, job satisfaction and turnover intention in emergency nurses. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 45, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Bryant, P.C.; Vardaman, J.M. Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht, J.P.; Trevor, C.O. Collective Turnover at the Group, Unit, and Organizational Levels: Evidence, Issues, and Implications. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 352–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Jagirani, T.S. Employee turnover in public sector banks of Pakistan. Market Forces College of Management Sciences 2019, 14, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Chon, K.S. An investigation of multicultural training practices in the restaurant industry: The training cycle approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judeh, M. Emotional intelligence and retention: the moderating role of job involvement. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2013, 7, 656–661. [Google Scholar]

- Kusluvan, S. Managing Employee Attitudes and Behaviors in The Tourism and Tourism Industry; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, S. Banking and financial sector reforms in Vietnam. ESEAN Econ. Bull. 2009, 26, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NavigosGroup. Nhân viên ngân hàng thu nhập triệu đồng mỗi tháng vẫn nghỉ việc. Available online: https://news.zing.vn/nhan-vien-ngan-hang-thu-nhap-10-30-trieu-dong-moi-thang-van-nghi-viec-post82.html (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Cafef. Hàng nghìn nhân viên ngân hàng nghỉ việc từ đầu năm đến nay: Nhân sự ngành ngân hàng đang bước vào thời kỳ bị cắt giảm diện rộng? Available online: http://cafef.vn/hang-nghin-nhan-vien-ngan-hang-nghi-viec-tu-dau-nam-den-nay-nhan-su-nganh-ngan-hang-dang-buoc-vao-thoi-ky-bi-cat-giam-dien-rong-20191017104021499.chn (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Ducharme, L.J.; Knudsen, H.K.; Roman, P.M. Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: The protective role of coworker support. Sociol. Spectr. 2007, 28, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.K.; Becan, J.E.; Flynn, P.M. Organizational consequences of staff turnover in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2012, 42, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, T.L.; Oser, C.B.; Aaron Johnson, J.; Knudsen, H.K.; Roman, P.M. Counselor turnover in substance abuse treatment centers: An organizational-level analysis. Sociol. Inq. 2007, 77, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Camara, N. Exploring the Relationship between Perceptions of Organizational Emotional Intelligence and Turnover Intentions amongst Employees: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. In New Ways of Studying Emotions in Organizations; Dulewicz, V., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2015; Volume 11, pp. 295–339. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Ayoun, B.; Eyoun, K. Work-Family conflict and turnover intentions: A study comparing China and U.S. hotel employees. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 17, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; Gursoy, D. Impact of job burnout on satisfaction and turnover intention: Do generational differences matter? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2013, 40, 210–235. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, L.; Zenasni, F.; Hodzic, S.; Ripoll, P. Understanding The Mediating Role of Quality of Work Life on the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, F.N.; Chai, L.T.; Aun, L.K.; Migin, M.W. Emotional intelligence and turnover intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2014, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.M.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, E.H.; Humphrey, R.H.; Pollack, J.M.; Hawver, T.H.; Story, P.A. The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 788–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Purdy, N.; Cho, J.; Almost, J. Antecedents and consequences of nurse managers’ perceptions of organizational support. Nursing Economic 2006, 24, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, B.; Fernández-Ferrín, P.; Varela, J.A.; Jaramillo, F. Emotions and salesperson propensity to leave: The effects of emotional intelligence and resilience. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 44, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Hardesty, D.M.; Murtha, B.R.; Sheng, S. Emotional intelligence in marketing exchanges. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence 1993, 17, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema 2006, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reis, D.L.; Brackett, M.A.; Shamosh, N.A.; Kiehl, K.A.; Salovey, P.; Gray, J.R. Emotional Intelligence predicts individual differences in social exchange reasoning. NeuroImage 2007, 35, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, K.; Arasu, R.; Kumar, S.A. The impact of emotional intelligence on employee work engagement behavior: An empirical study. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, O. Understanding and Developing Emotional Intelligence. In Knowledge Solutions: Tools, Methods, and Approaches to Drive Organizational Performance; Serrat, O., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaveni, R.; Deepa, R. Emotional intelligence–a soft tool for competitive advantage in the organizational context. ICFAI J. Soft Ski. 2011, 5, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.U.; Nazir, N.; Kazmi, S.; Khalid, A.; Kiyani, T.M.; Shahzad, A. Work-life conflict and turnover intentions: Mediating effect of stress. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G.G.; Shaw, J.D. Voluntary turnover, social capital, and organizational performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I.; Waseem, M.; Sikander, S.; Rizwan, M. The relationship of turnover intention with job satisfaction, job performance, leader member exchange, emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2014, 4, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.J.; Ao, C.T.D. The mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on turnover intention, in the relationships between pay satisfaction and work–family conflict of casino employees. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 206–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H. Employee Turnover: Causes, Consequences, and Control; Addison-Wesley publishing: Philippines, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderate tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, B.N.; Giao, H.N.K. The impact of perceived brand globalness on consumers’ purchase intention and the moderating role of consumer ethnocentrism: An evidence from Vietnam. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durup, R.J.M. An Integration Model of Work and Family Stress: Comparisons of Models; Dahousie University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olorunfemi, D.Y. Family-work conflict, information use, and social competence: a case study of married postgraduate students in the faculty of education, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2009, 235, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.A.; Lee, B.W.; Wu, S.T. The relationships among work-family conflict, turnover intention and organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry of Taiwan. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 1120–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.; Maertz, C.; Person, A.; Keough, S. Work-family conflict: A model of linkages between work and family domain variables and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.J.; Kim, Y.T. Work-family conflict, work-family facilitation, and job outcomes in the Korean hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelic, K.K.; Tekavcic, M. Work-family conflict: A review of antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 18, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, M.J.; Cooper, C.L. Shattering the Glass Ceiling, the Woman Manager; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg, H.J. Staff burnout. Journal of Soc. Issues 1974, 1, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, A.; Aronson, E.; Kafry, D. Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R.L. Job burnout: Prevention and remedies. Public Welf. 1978, 36, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toker, S.; Biron, M. Job burnout and depression: unraveling their temporal relationship and considering the role of physical activity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, B.; Ali, M.; Naseem, K.; Moeed, A.; Ahmed, J.; Hamid, M. Impact of trait mindfulness on job satisfaction and turnover intentions: Mediating role of work–family balance and moderating role of work–family conflict. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.S. Why emotional intelligence should matter to management: A survey of the literature. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2009, 74, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesar, S.; Koortzen, P.; Oosthuizen, R.M. The relationship between emotional intelligence and stress management. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2009, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.J. Toxic Emotions at Work; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, F.; Naeem, S.; Khanzada, B.; Butt, K. Impact of emotional intelligence on turnover intention, job performance and organizational citizenship behavior with mediating role of political skill. J. Health Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 6, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.; Feldman, D. Organizational tenure and job performance. J. Manag. 2010, 35, 1220–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, W.M.; Shabir, A.; Safdar, S.M.; Akhtar, S.M. Impact of emotional intelligence on turnover intentions: The role of organizational commitment and perceive organizational support. J. Account. Mark. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaghan, J.A.; Buda, R.; Eisner, A.B. An examination of the role of emotional intelligence in work and family conflict. J. Manag. Issues 2007, 19, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A. The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behavior and outcomes: An examination among senior managers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2003, 18, 788–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, J.; Niu, Q.; Wang, L. Work–family conflict and job satisfaction: Emotional intelligence as a moderator. Stress Health 2013, 29, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.M.; Al-Shaikh, F.N. Emotional intelligence at work: links to conflict and innovation. Employee Relations 2007, 29, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, B.; Jordan-Evans, S. Love ’Em or Lose ’Em: Getting Good People to Stay; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc: Williston, ND, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.; Rehman, M.Z.; Raza, I. Impact of family friendly policies on employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intention: A study on work-life balance at workplace. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2010, 2, 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Collins, K.M. Career involvement and family involvement as moderators of relationships between work-family conflict and withdrawal from a profession. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Armstrong, J. Further examination of the link between work–family conflict and physical health: The role of health-related behaviors. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J. Low Emotional Intelligence and Mental Illness; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, T.W.; Hur, W. Emotional intelligence, emotional exhaustion and job performance. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2011, 39, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-S.; Law, K. The effects of leader and follower emotional intel- ligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.; Shumaila, S.; Azhar, M.; Sadaqat, S. Work-family conflicts: Relationship between work-life conflict and employee retention-A comparative study of public and private sector employees. Interdiscip. J. Res. Bus. 2011, 1, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T.D. Altering the effects of work and family conflict on exhaustion: Telework during traditional and nontraditional work hours. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Still, M. Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharakhani, D.; Zaferanchi, A. The effect of job burnout on turnover intention with regard to the mediating role of job satisfaction. Arumshealth 2019, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layne, C.; Hohenshil, T.; Singh, K. The relationship of occupational stress, psychological strain, and coping resources to the turnover intensions of rehabilitation counselors. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2004, 48, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Khan, Q.; Naz, A.; Khan, N. Job rotation on job burnout, organizational commitment: A quantitative study on medical staffs Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Stud. 2017, 3, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is Emotional Intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sergio, R.P.; Dungca, A.L.; Gonzales, J.O. Emotional intelligence, work / family conflict, and work values among customer service representatives: Basis for organizational support. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. 2015, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weinzimmer, L.G.; Baumann, H.M.; Gullifor, D.P.; Koubova, V. Emotional intelligence and job performance: The mediating role of work-family balance. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 157, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.S.; Hasan, A. Relationship between emotional intelligence and employee turnover rate in FMCG organizations. Pak. J. Commer. Social Sci. 2013, 7, 198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchinson, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, S.; Turunc, O.; Celik, M. The impact of perceived organizational support on work–family conflict: Does role overload have a mediating role? Econ. Ind. Democr. 2013, 34, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Demoulin, S.; De Wilde, M. Perceived organizational support and employees’ well-being: The mediating role of organizational dehumanization. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, C.; Vandenberghe, C. Perceived organizational support, emotional exhaustion, and turnover: The moderating role of negative affectivity. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2016, 23, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu Subhash, C. Effects of supportive work environment on employee retention: Mediating role of organizational engagement. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Hu, J. Person-organization fit, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: An empirical study in the Chinese public sector. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2010, 38, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyrek, İ.H.; Turan, A. Effects of individual characteristics and work related factors on the turnover intention of accounting professionals. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 7, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. How emotional intelligence relates to job satisfaction and burnout in public service jobs. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 84, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. Organizational politics, job attitudes, and work outcomes: Exploration and implications for the public sector. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 57, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giao, H.N.K.; Vuong, B.N. Giáo Trình Cao Học Phương Pháp Nghiên Cứu Khoa Học Trong Kinh Doanh Cập Nhật SmartPLS; Nhà Xuất Bản Tài Chính: TP. Hồ Chí Minh, Việt Nam, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giao, H.N.K.; Vuong, B.N.; Quan, T.N. The influence of website quality on consumer’s e-loyalty through the mediating role of e-trust and e-satisfaction: An evidence from online shopping in Vietnam. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publication, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong, B.N.; Suntrayuth, S. The impact of human resource management practices on employee engagement and moderating role of gender and marital status: An evidence from the Vietnamese banking industry. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, B.N.; Hieu, V.T.; Trang, N.T.T. An empirical analysis of mobile banking adoption in Vietnam. Gestão e Soc. 2020, 14, 3365–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | The Minimum Value of Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-emotion appraisal | 4 | 0.851 | 0.481 |

| Others’ emotion appraisal | 4 | 0.891 | 0.716 |

| Use of emotion | 4 | 0.865 | 0.608 |

| Regulation of emotion | 4 | 0.913 | 0.768 |

| Perceived organizational support | 7 | 0.897 | 0.513 |

| Work interfere with family | 5 | 0.928 | 0.724 |

| Job burnout | 4 | 0.906 | 0.714 |

| Turnover intention | 4 | 0.743 | 0.314 |

| N = 722 | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 463 | 64.1 |

| Male | 259 | 35.9 | |

| Marital status | Single | 271 | 37.5 |

| Married | 451 | 62.5 | |

| Age group | 18–25 | 140 | 19.4 |

| 26–35 | 349 | 48.3 | |

| 36–45 | 200 | 27.7 | |

| >45 | 33 | 4.6 | |

| Income (1 million VND ≈ $ 43.25) | Under 10 million VND | 220 | 30.5 |

| 10–20 million VND | 349 | 48.3 | |

| 20–30 million VND | 117 | 16.2 | |

| Above 30 million VND | 36 | 5.0 | |

| Education | College/University | 581 | 80.5 |

| Postgraduate | 141 | 19.5 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Age | EI | Edu | Gen | Inc | JB | MS | OEA | POS | ROE | SEA | TI | UOE | WFC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | - | - | - | (1) | 0.071 | 0.108 | 0.149 | 0.083 | −0.028 | 0.124 | 0.069 | 0.048 | −0.016 | 0.091 | −0.058 | 0.093 | −0.029 |

| EI | 0.921 | 0.922 | 0.931 | 0.758 | (0.871) | −0.035 | 0.028 | 0.078 | −0.556 | 0.016 | 0.819 | 0.554 | 0.797 | 0.861 | −0.517 | 0.761 | −0.472 | |

| Edu | - | - | - | - | (1) | −0.012 | 0.077 | 0.009 | 0.050 | 0.050 | −0.061 | −0.091 | −0.094 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.051 | ||

| Gen | - | - | - | - | (1) | −0.085 | −0.063 | −0.094 | −0.014 | 0.030 | 0.067 | 0.004 | −0.055 | 0.034 | −0.067 | |||

| Inc | - | - | - | - | (1) | 0.058 | 0.121 | 0.055 | 0.018 | 0.096 | 0.014 | −0.057 | 0.089 | −0.072 | ||||

| JB | 0.894 | 0.895 | 0.926 | 0.759 | (0.871) | −0.076 | −0.490 | −0.497 | −0.525 | −0.407 | 0.606 | −0.360 | 0.462 | |||||

| MS | - | - | - | - | (1) | 0.106 | −0.020 | −0.067 | −0.029 | −0.047 | 0.042 | 0.000 | ||||||

| OEA | 0.879 | 0.880 | 0.917 | 0.734 | (0.857) | 0.362 | 0.481 | 0.652 | −0.383 | 0.507 | −0.267 | |||||||

| POS | 0.891 | 0.893 | 0.916 | 0.611 | (0.782) | 0.533 | 0.466 | −0.601 | 0.424 | −0.677 | ||||||||

| ROE | 0.873 | 0.874 | 0.913 | 0.724 | (0.851) | 0.608 | −0.529 | 0.460 | −0.506 | |||||||||

| SEA | 0.810 | 0.819 | 0.877 | 0.642 | (0.801) | −0.418 | 0.534 | −0.395 | ||||||||||

| TI | 0.807 | 0.842 | 0.875 | 0.641 | (0.800) | −0.330 | 0.555 | |||||||||||

| UOE | 0.863 | 0.864 | 0.907 | 0.710 | (0.842) | −0.350 | ||||||||||||

| WFC | 0.913 | 0.915 | 0.935 | 0.742 | (0.862) |

| JB | OEA | ROE | SEA | TI | UOE | WFC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.068 | ||||||

| EI | 1.479 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.741 | 1.000 | 1.442 |

| Edu | 1.024 | ||||||

| Gen | 1.054 | ||||||

| Inc | 1.065 | ||||||

| JB | 1.654 | ||||||

| MS | 1.056 | ||||||

| POS | 2.124 | 2.190 | 1.442 | ||||

| WFC | 1.896 | 1.964 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | PathCoefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistics | p-Values | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | → | UOE | 0.761 | 0.021 | 36.527 | 0.000 | ||

| EI | → | ROE | 0.797 | 0.016 | 50.307 | 0.000 | ||

| EI | → | SEA | 0.861 | 0.010 | 89.384 | 0.000 | ||

| EI | → | OEA | 0.819 | 0.013 | 64.661 | 0.000 | ||

| H1 | EI | → | TI | −0.097 | 0.040 | 2.435 | 0.015 | Supported |

| H2 | EI | → | WFC | −0.140 | 0.032 | 4.392 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | WFC | → | TI | 0.169 | 0.043 | 3.953 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | EI | → | JB | −0.381 | 0.030 | 12.527 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | WEC | → | JB | 0.164 | 0.054 | 3.019 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H6 | JB | → | TI | 0.345 | 0.037 | 9.258 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H7 | POS | → | TI | −0.261 | 0.050 | 5.164 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H10 | POS | → | WFC | −0.600 | 0.033 | 18.423 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H11 | POS | → | JB | −0.175 | 0.048 | 3.636 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| H14 | Gender | → | TI | −0.015 | 0.026 | 0.585 | 0.559 | Not supported |

| Age | → | TI | −0.013 | 0.028 | 0.483 | 0.630 | Not supported | |

| Edu | → | TI | −0.019 | 0.025 | 0.786 | 0.432 | Not supported | |

| Income | → | TI | −0.049 | 0.026 | 1.846 | 0.065 | Supported | |

| Marital status | → | TI | −0.017 | 0.025 | 0.681 | 0.496 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | Mediating Effect | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | EI→WFC→ TI | −0.097 * | −0.024 *** | −0.252 *** | Partial Mediation | Supported |

| H8 | EI→JB→ TI | −0.131 *** | Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giao, H.N.K.; Vuong, B.N.; Huan, D.D.; Tushar, H.; Quan, T.N. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051857

Giao HNK, Vuong BN, Huan DD, Tushar H, Quan TN. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051857

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiao, Ha Nam Khanh, Bui Nhat Vuong, Dao Duy Huan, Hasanuzzaman Tushar, and Tran Nhu Quan. 2020. "The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051857

APA StyleGiao, H. N. K., Vuong, B. N., Huan, D. D., Tushar, H., & Quan, T. N. (2020). The Effect of Emotional Intelligence on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from the Banking Industry of Vietnam. Sustainability, 12(5), 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051857