1. Introduction

The concept of “open government” was coined in the United Kingdom in the late 1970s. This concept aimed to reduce bureaucratic opacity and to encourage the involvement of citizens in the evaluation and control of public agencies and their performance thus creating a thirst for new management perspectives [

1,

2]. Over the course of the last decade, the concepts of “governance” and “sound governance” have also become common in the context of the European Commission [

3]. In 2009, it was president Obama [

4] who first defined the main principles of Open Government in his “Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government” as transparency, participation and collaboration. In Spain, the Basque Government was the first to commit to the principles of open government; the online portal “Irekia” (meaning ‘open’ in Basque language) [

5] is a clear example of this. In 2011, Open Government Partnership (henceforth, OGP) endorsed an Open Government Declaration that set a series of minimum common standards for all initiatives [

6]. The OGP formally launched on 20 September 2011, when the eight founding governments (Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, South Africa, United Kingdom and United States) endorsed an Open Government Declaration, and announced the action plans for their countries. Since September, OGP has welcomed the commitment of 47 additional governments to join the Partnership.

One of the main benefits of the implementation of open government strategies is to establish greater confidence in the government. Trust is a result of Open Government that can reinforce its performance in other aspects. In addition, if citizens trust the government and their specific policies, they may be more willing to pay (fees, contributions, taxes) to support and finance those policies. On other hand, another benefit is to guarantee better results at the lowest cost. The co-design and implementation of policies, programs and provision of services with citizens, businesses and civil society offers the potential to exploit a broader repository of ideas and resources. Also, the open government increases compliance levels as making people part of the process helps them understand the challenges of reform and can help ensure that decisions made are perceived as legitimate. To promote innovation and new economic activities is another goal of the open government. The commitment of citizens is increasingly and is recognized as a driving force for innovation and the creation of value in the public and private sectors. Moreover, the open government ensures equity of access to the formulation of public policies by reducing the threshold for access to decision processes that people face as barriers to participation. And finally, to govern under the principles of open government improves effectiveness by taking advantage of the knowledge and resources of citizens who otherwise face barriers to participate. Citizen participation can guarantee that policies are more specific and meet their needs, eliminating potential waste. However, effective participation requires an understanding of the evolving relationship between the human and technological dimensions in order to prepare citizens for this new technological era [

7,

8]. A detailed description of all these benefits can be found in [

1]. The open governance approach also has some weaknesses. People are considered to be the heart of any open government initiative since their involvement and participation is crucial for its own success [

9,

10]. For this reason, it is important to take into account the main drivers for citizen’s participation and collaboration. To some extent, the success of the open government initiative relies on citizens’ willingness to interact with the institution and provide input on the given task [

11]. To overcome this potential weaknesses, Schmidthuber et al. [

12] suggested the implementation of a reward system to increase the platform interaction among participants but also to include elements of gamification to increase their enjoyment feeling.

Ortiz de Zárate (2012) introduced a descriptive model, called “LUDO”, to understand and classify open government initiatives [

13]. The main goals of LUDO are to contribute to the introduction of open public policies in a systematic way, to ensure that participation initiatives are well designed, to clarify the role of the public sector in the process, and finally to establish a clear contractual relationship with internal and external stakeholders.

According to the LUDO model, the grade of opening of an initiative can be classified into the following three levels: Information, Query and Delegation. The information level is the initial basic requirement of any opening strategy. It can not be said that power is being returned to the citizens, but it is the first step to empower it, at least the essential thing to make it possible to participate in the following levels. The communication that is established in this level is eminently unidirectional, although in a secondary way it can collect certain feedback. The query level can be considered that at this level a part of the power is distributed, establishing a bidirectional communication that aims to maintain a conversation relationship. Finally, the delegation level involves the return of power to the public in the specific area of public management that is the object of the initiative, and society will play the role traditionally exercised unilaterally by the Administration. In this maximum degree of openness, the Administration acts as a platform supporting a distributed network.

An open government initiative is closely related to e-government based on the extensive utilization of information and communication technologies (ICTs) towards an open government and available data and communication among all stakeholders [

14]. In recent years, many web platforms have been designed by applying the open government principles under different European projects.

In IMPACT project coordinated by Gordon in 2013 [

15] a toolbox was developed for supporting deliberations about public policy. Users can visualize arguments about policy, can make a consultation and can simulate the legal effects of policy proposals in real and hypothetical cases. The toolbox is based on computational models of argumentation. In the UbiPOL project coordinated by Irani in 2013 [

16] an ubiquitous platform is developed for the participation of citizens in everyday life. The application is designed for a mobile framework and information about relevant policies is provided depending on the localization of the citizen. The Liv+Gov project coordinated by Thimm in 2015 [

17] provided a mobile government solution that allows citizens to accurately express their needs to government by using a variety of mobile sensing technologies available in their smartphones. The PADGETS project coordinated by Charalabidis in 2012 [

18] consisted in building politics gadgets, which are distributed in social networks. The interactions between users and gadgets are analyzed by RapidMiner commercial package. The goal of the politics gadgets is to allow politicians to throw political messages during campaign periods and to create reports with opinion mining results. In the WeGov project coordinated by Walland in 2012 [

19], the tool selected only the important post and classifies users according to their behavior. A further improvement is required to prepare the toolbox for commercial-quality release. The CROSSOVER project coordinated by Misuraca in 2013 [

20] consisted in bringing the links between different global communities promoting the exchange of knowledge and implementing an international roadmap based on ICT solutions for policy modeling. The NOMAD project coordinated by Charalabidis in 2015 [

21] extracted information from the web and analyzed the sentiment of the citizens regarding the policy. Finally, in the LISBOA PARTICIPA project coordinated by Caçador in 2017 [

22], a platform was designed for promoting the participation of citizens in Lisboa to decide where to better invest public money. Thus, the models of interaction with citizens were redefined. The participation is divided into 3 phases: firstly, citizens present their proposals, then a technical analysis is made by the different municipal departments according to the areas of competence transforming the ideas to projects. Finally, the projects are submitted to citizens to vote and decide which are the winning ideas.

Traditionally, the World Wide Web has been used by organizations and individuals as a powerful tool for communication. In education, it provides with on-demand access to any information, anytime and anywhere, and material for a given course or for tutoring [

23]. More specifically, web-based tools have been successfully applied for students’ assessment [

24,

25] as well as promoting collaborative learning [

26,

27]. Despite the variety of existing web applications, to the best of our knowledge, none of them have been applied to the strategic management in higher education institutions. Therefore, our main contribution to the existing works is to present an innovative sound practice, based on technological tools, this time applied to the design and the follow up of the strategic planning process. Thus, on the one hand the design of the strategy of the organization is carried out by the main actors or stakeholders in the university such as students, professors and administration personnel, and the other hand, the technologies are used for supporting the co-production and collaborative development, whereby stakeholders are partners, as opposed to customers, in the delivery of new public services defined in the university’s strategy.

The main contributions of this paper are twofold. Firstly, an innovative approach, such as the adoption of the stakeholder approach versus the traditional product-service orientation used until now in most of the university strategic plans. Secondly, the open e-government based elaboration of the strategic plan by all members of the university community through the use of specialized technologies for citizen consultation and participation. To the best of author’s knowledge, it is the first time that a strategic plan has been developed in a Spanish university in an open and collaborative manner using new technologies as well as adopting this stakeholder point of view.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 makes a description of the digital platform designed for interactions among stakeholders and people from the government.

Section 3 describes the methodology followed in the participation process shown in this paper.

Section 4 presents an analysis of data extracted from the participation in the platform.

Section 5 closes the paper giving some final conclusions.

2. Web Platform: Technical Description

New technological trends have emerged recently, such as the cloud computing, which offer solutions to particular needs arising in higher education institutions. In spite of the initial rejection to use the cloud for reasons related to the security of information and data protection, the cloud computing is a fact today. In such scenario, to buy technology is being transformed into buying of services to providers and payment for their use, under new concepts such as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Software as a Service (SaaS) y Platform as a Service (PaaS).

The UserVoice (

www.UserVoice.com) software used for carrying out this innovative experience is based on the SaaS business model. This software does not have any special technical requirement and can be integrated with other applications or websites.

In this work, UserVoice has been integrated alongside with a website based on the Wordpress (

www.wordpress.com) open source technology. Recently, the UserVoice developers have also created an API, which allows to generate an API client in an administration console and the installation of a software development kit depending on the programming language (php, java, python ruby or C#).

The UserVoice software is very flexible and provides with many possibilities for its integration with a website. Namely, it is possible to add widgets, to customize the portal changing logos, colors or using templates CSS or HTML, to be embedded in an iPhone application using the native IOS SDK of UserVoice, integration with the identity management system via encrypted token, SAML or Active Directory, etc.

Basically, the most used features of the UserVoice tool are feedback forums and in-app widgets to listening opinions of stakeholders, a vote system called SmartVote that offers the possibility to the stakeholders to mark their priorities, a support ticket system to know the trace and respond to questions and requests of the stakeholders, and finally, a repository with answers to common questions for helping to stakeholders to find easily the information desired.

The most important features related to the vote system, feedbacks and the e-ticketing tool are described below. The vote system is a smart vote, which shows users a set of ideas and asks them to choose which idea they want you to build next. When a user picks an idea, they can choose to just “pick” it or they can “pick+subscribe” which subscribes them to updates. SmartVote has users rank ideas. While users creating and supporting one other’s ideas helps you gauge interest, it doesn’t let you see how users would rank ideas. SmartVote has users prioritize ideas as they pick between them. It lets you see how ideas are ranked against one another and which ideas consistently come out on top. You can also auto-prompt users for SmartVote, so you can engage your more silent users that have valuable feedback to share, but might not post on your forum. SmartVote is based on the creation of polls, being a poll a set of ideas on public forums that you want to test, and uses the Glicko rating system (GRS) to look for clear winners in a set of suggestions or ideas. The GRS was invented by Mark Glickman and is a method for assessing a player’s strength in games of skill, such as Chess and Go. In our case, the GRS evaluates the weight of the ideas composing of the pool using the measure Ratings Deviation (RD) defined by the following equation:

where

is the initial rating,

t is the time elapsed from the last idea, 350 is the default value for non-ranked ideas and

c is a parameter with the value

usually.

Regarding to feedback received by the stakeholders of any institution, UserVoice offers the possibility of assigning the Contributor role to anyone in your company and this role can capture feedback on behalf of stakeholders and have it saved directly in UserVoice. In particular, the Contributor has a sidebar which is a bookmark that can be opened on top of a web page or app allowing to capture feedback from an email or support ticket and link it to ideas in UserVoice. In addition, a Contributor can quickly look up any stakeholder to see their previous feedback and view status updates for existing feedback. For the management of the feedbacks, UserVoice can be integrated with the well-known JIRA e-ticketing system used by 75,000 companies in 122 countries. Once the Jira integration has been installed and configured, a new section labeled “Linked Jira Issues” will be visible in UserVoice when the admins view a new suggestion or idea. From here, UserVoice items can be linked to existing Jira issues (or create new ones), and see details of the linked Jira issues at a glance. JIRA is a tool developed by Australian Company Atlassian and it is used for bug tracking, issue tracking, and project management. The JIRA dashboard consists of many useful functions and features, which make handling of issues easy.

3. Method

European higher education institutions have experienced an unprecedented transformation due to the new social and economic paradigms and the convergence to the European higher education area. In this context, stressed by the global financial crisis, the strategic planning process [

28,

29] has become a crucial tool for the university governance, sustainability and management, ensuring the continuous adaptation of the University to the challenges from the environment and thus consolidating its leadership in education, research, innovation, social responsibility and knowledge transfer; all in a circle self-feeding process throughout life. Inherited from business management, the strategic perspective implies an internal reflection, about resources and capabilities of the institution, but also external in order to detect opportunities and threats in the environment. Strategic Planning is a means of establishing major directions for the university, school or department. It is a structured approach to anticipating the future and exploiting the inevitable [

30], but also an appropriate response to turbulence [

31].

In this paper, we describe a sound open government practice, based on a web platform, for innovating in the strategic planning process, but also based on the stakeholders’ approach [

32,

33]. For this purpose, the LUDO methodology is applied. The application of the LUDO model to the participatory process for the preparation of the strategic plan of the university, as well as facilitating the design of the initiative, can help to establish clear conditions for both the university community and the citizens to participate and, on the other hand, to reflect and assume with security for the management team the implications that the opening process entails. On the one hand, this establishes a clear social contract between both members of the university community and citizens who freely decide to participate. On the other hand, the board of directors that instead of defining and designing in isolation the strategic plan that must be submitted to the university senate to approve the program of actions to develop in the next few years, decides to open it to the participation of all. When an open government initiative is carried out, the first thing that must be understood is what is being opened. Public policies are constructed according to a continuous cycle of reflection and action, analysis and execution, which superficially resembles other cycles such as, for example, the Deming’s cycle PDCA (plan-do-check-act), well-known as continuous improvement cycle, which constitutes the core of quality management systems. Perhaps too often, this cycle is applied with less awareness, and therefore with less clarity to the desired. The cycle of public policies facilitates understanding and describing political action, so it should be clearly applied in all government actions as is the case of a strategic plan of an organization for next years. But it has more relevance even when an important step is taken, as it is to open a political action to participation. In this way, in addition to doing it with clarity, it is done with security. Following the simple formulation proposed by the LUDO model for the process or cycle of public policies there are four phases, which are define, design, do and assess. These phases have inspired the methodology describe below.

The strategic plan promoted by the vice chancellor for ICT, quality and innovation with the participation of the general directorate of strategy and innovation, is divided into three key stages:

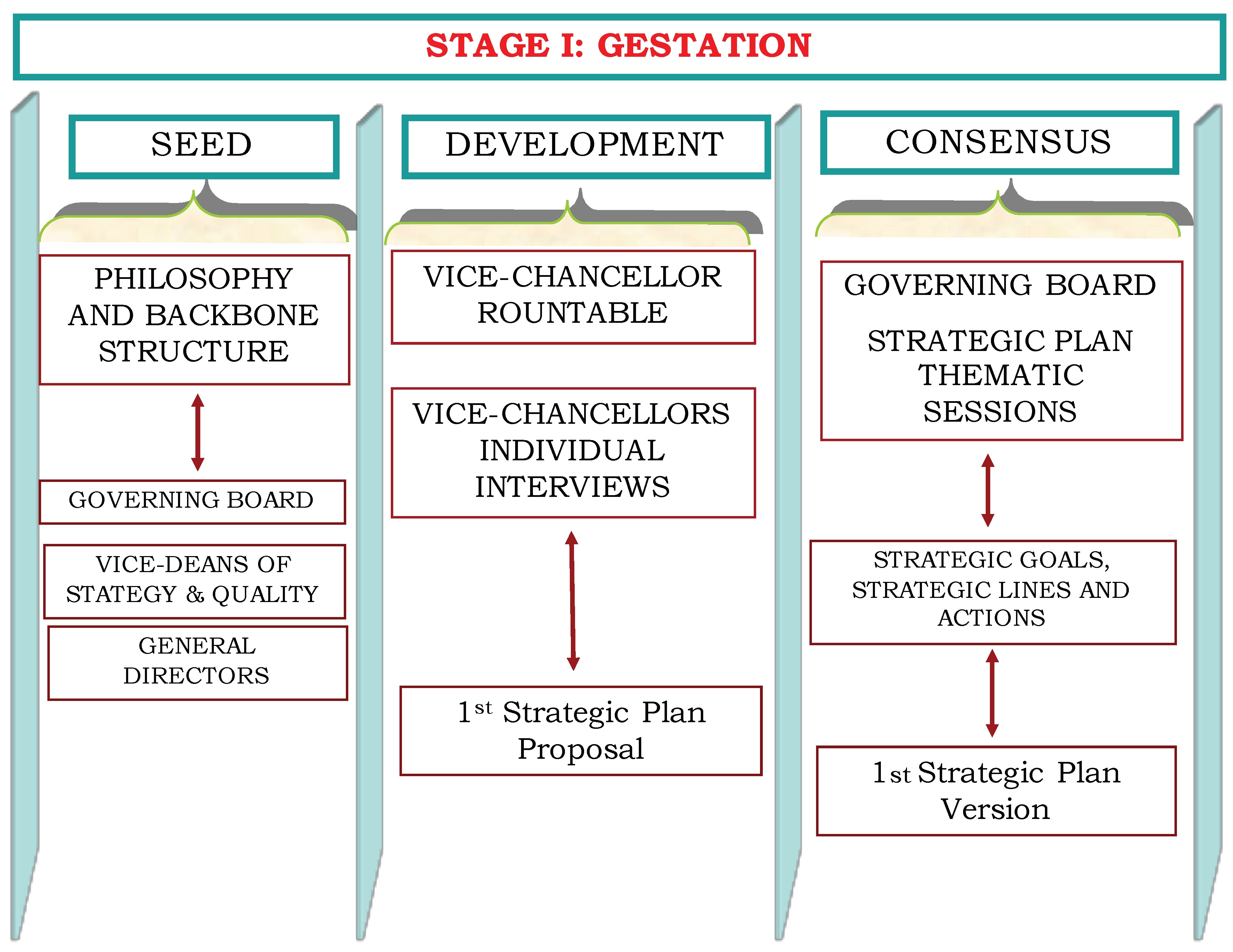

3.1. Stage I: Gestation

The first stage began with the initial strategic proposal presented by the general directorate of strategy and innovation to the governing board. This proposal was also presented to the university board of general directors and the faculties’ vice deans of strategy and quality during a series of round tables. Specifically, the new philosophy now set forth is based on the stakeholders’ approach, which is seen as an alternative to the traditional product-service orientation adopted in traditional strategic plans [

34]. This new philosophy provides a framework for the improvement of mutual cooperation among all members of the university community in order to achieve the strategic goals. Moreover, the institution is perceived as a social agent and it is assumed to be transparent, responsible and value-creating. The university’s stakeholders are perceived as a target towards which institutional policies are directed, thus increasing their commitment to the university goals and a sense of organizational unity. The support of stakeholders and their willingness to participate is essential if this vision is to be achieved. There is little doubt that the resulting plan is undoubtedly enriching, since each group brings a unique perspective to the strategic planning process. Once the approach had been outlined, the vice chancellors suggested a few initial ideas for discussion in joint working sessions and in-depth interviews, resulting in a first draft of the Strategic Plan. A general diagram describing this phase is depicted in

Figure 1.

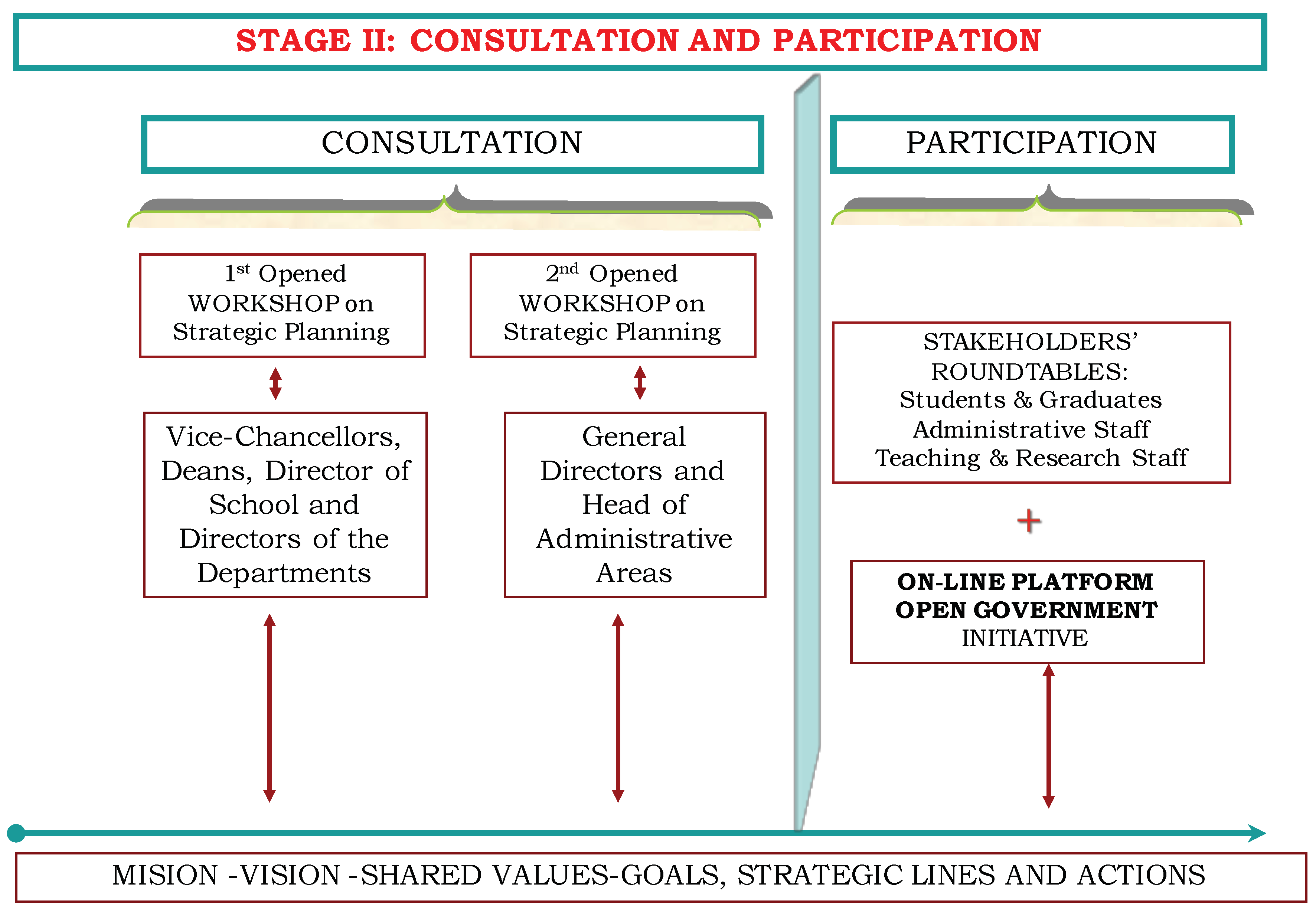

3.2. Stage II: Consultation and Participation

The second stage began by creating awareness and promoting open debate and reflection under the heading of “Open Workshops on Strategic Planning”. A general scheme of the process followed for the consultation and participation stage is shown in

Figure 2. The first of these workshops brought together various vice-chancellors, deans, directors of schools and directors of departments; the second gathered the heads of the different administrative departments and directorates. In addition, three key round tables were organized for the primary university stakeholders: administrative staff, teaching and research staff, and students and graduates. As Axelsson et al. [

35] suggested that understanding different stakeholders’ expectations is also crucial in order to prepare and anchor changes in e-service development and implementation through information and training. All stakeholders possess knowledge and expertise that can provide valuable input when developing e-services [

36]. Consequently, in all these working sessions, which were conducted by experts of the UNESCO Chair in Higher Education Management [

37], our community discussed, and agreed upon, important elements of the new strategic plan, such as the university mission, vision and shared values. The main competitive advantages of our university were also considered during the debates. Once identified, the strategic objectives were reformulated in order to make appropriate use of, maintain, or even create these unique advantages, seeking the features which make our university unique [

38].

In addition to the two open workshops and three round tables, we also conducted in-depth interviews on a sample of the university director board applying the sequential procedure described by Creswell in [

39]. First, we invited to participants to attend in-depth interviews. As a methodological support for data collection, we carry out a semi-structured interview, where respondents are asked about relevant aspects to ensure an effective strategic plan in the university. With respect to the data collection, audio recordings corresponding to 12 interviews were made. The average duration of each interview was about 30 min. All interviews have to be treated and validated within a week. Thus, a transcript of each interview was sent to each participant to make the necessary corrections or clarifications. Next, all recordings were transcribed and analyzed using the MAXQDA data analysis software [

40]. It is a powerful tool for textual analysis based on qualitative data. The methods used in MAXQDA are based on the methodology of social research, especially for grounded theory, qualitative content analysis, field research methods, ethnographic methods and socio-economic research models. Later, we applied the coding guide of Tesch [

41] for the qualitative data analytic process and grouped the data by assigning the coding nodes. At this stage of the analysis, the issues that received the most attention during interviews and the most common concepts and ideas emerged. Finally, the process ends with an interpretation. For that purpose, the opinions of the interviewees were compared and contrasted, giving rise to the main results and findings.

After this, the draft of the strategic plan was presented to the university community and society in general by means of an online platform in order to promote participation, debate and consultation. This platform was based on UserVoice and Wordpress software.

This online platform was active throughout one moth in order to receive the opinions and votes of all the participants. These proposals were analyzed and shortlisted prior to the drafting of the final version for their inclusion in the strategic plan. These final versions aim to reflect the expectations of our community as widely as possible way. This is the first attempt to bring our institution closer to the principles of open government, an endeavor which the regional government of Andalusia has wholeheartedly supported. It is an innovative initiative aimed at promoting new participatory dynamics and collaborative work based on the operation of technological tools. Comments shared on the platform are moderated according to the established terms of service.

It must be taken into account that in an initiative with a maximum level of openness, that is to say third level, the power of decision and execution of the government action, which is object of the initiative, is no longer to be shared with citizens, but rather it is returned completely to them. It should be clearly noted that in this pilot experience, the final decision on the proposals that are incorporated or not into the strategic plan is made by the government team. However, there is a possibility to reach the third level, called delegation, in the execution stage of the actions programmed in the strategic plan by means of working groups. One of the objectives of this initiative is to promote the cross-cutting development of the plan itself, favoring the constitution of working groups around the objectives and actions. If this degree of commitment is reached by the university community and these groups are finally created, the level of openness will be a level three of delegation, being the action or programmed actions executed by the working groups.

3.3. Stage III: Review and Approval

During one month, the governing board analyzed all the proposals set forth by the university community during the consultation and participation stages in order to prepare the final version of the strategic plan. Finally, three months later, the document was presented for approval before the university senate.

Finally, the approved strategic plan consists of four objectives deployed in twenty-four actions that affect students and graduates and are related to academic training, employability, entrepreneurship and internationalization. For the professors and researchers, four objectives divided into fourteen actions related to the incorporation of talent through new researchers, the attraction of financial resources and internationalization were set out. Administration and services staff were the target of four objectives split into twenty-two actions related to productivity, innovation and management efficiency evaluated by means of user satisfaction. Finally, as a novelty, the university board of directors appeared as internal stakeholders, for which a strategic objective composed of four actions related to institutional commitment, internal communication and co-responsibility was established.

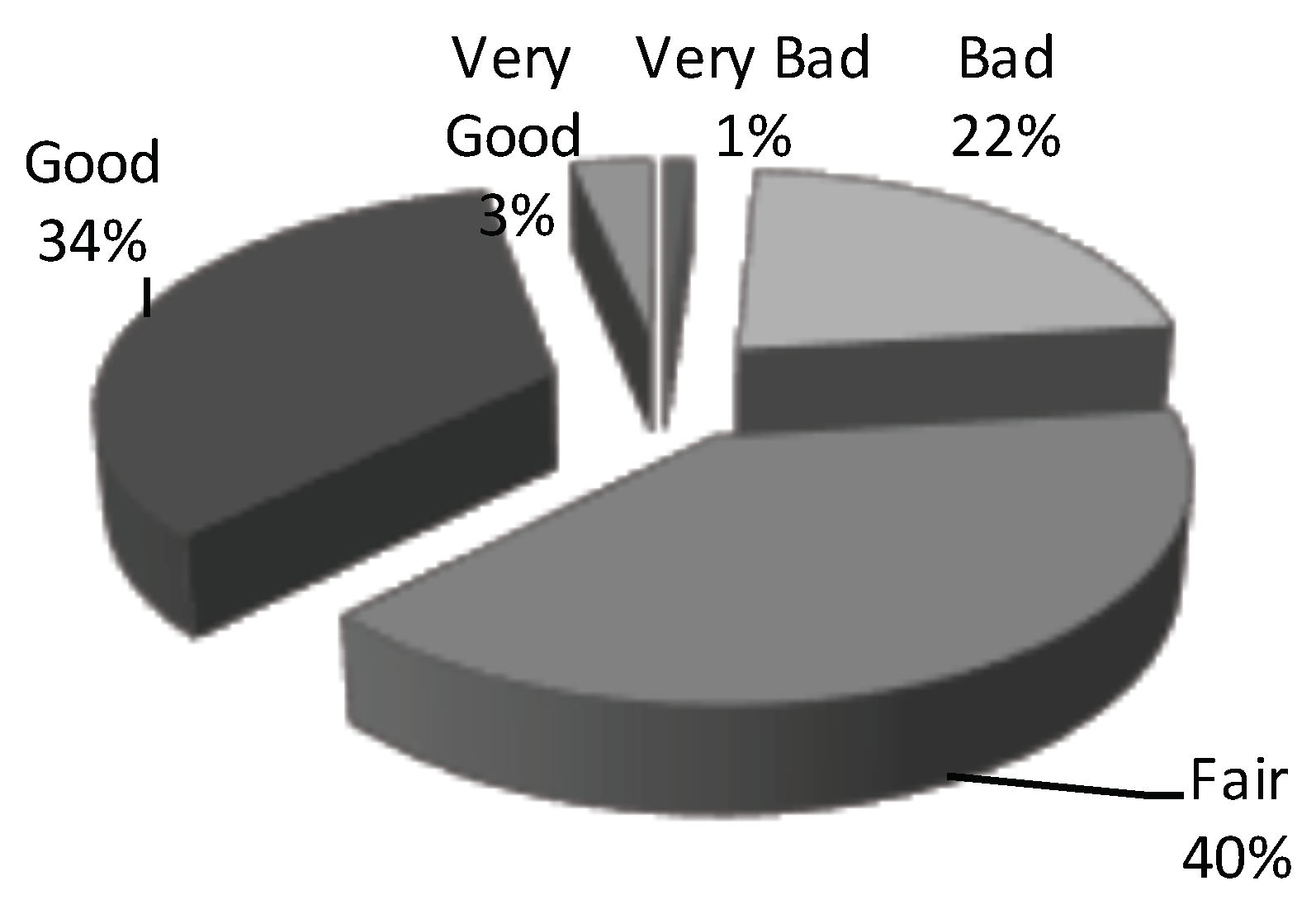

3.4. Stage IV: Monitoring

Once the strategic plan was approved, the online platform for the annual monitoring of the strategic plan is launched again to the whole university community so they can openly rate, comment and vote the values reached by the performance indicators (both qualitative and quantitative) corresponding to short term actions taken during the first year of implementation. In this first follow-up annual report, 91 actions have been assessed by the university community through the online platform, receiving 825 votes and obtained an average score of 3.5 out of 5. Two actions should be highlighted: “Achieving budget balance” and “Diversification and increase of funding sources”. Both of them have been rated with maximum score, 5 out of 5 (very good) and depend on the university general manager. Such actions framed within the strategy “Establish measures of budgetary balance”, contribute to ensure sufficient funding to the institution that permits long-term sustainability, promotes transparency and accountability and strengthens our vocation of public service. Moreover, the “Third Sector Project: A Program to promote research, training and action on participation, inclusion and social commitment”, was given the same rating, 5 out of 5. The distribution of rating obtained by the 91 actions assessed is shown in the

Figure 3.

4. Results

This paper describes the application of an innovative and successful open government practice to the university’s strategic planning process. The key principles of the open government philosophy are transparency, openness, participation and collaboration. In this regard, we have applied technological tools (UserVoice software and Wordpress) in the design of an online platform in order to involve not only the university’s primary (students, teachers, researchers and administrative staff) but also secondary stakeholders (firms, institutions, suppliers, etc.), which can now contribute with their proposals and votes to the achievement of the university’s strategic goals.

This online platform was active over the course of one month so that all the proposals for the new strategic plan could be received and voted on openly. In its first month of existence, the online platform received 3269 visits and 1875 new visitors. Around 100 proposals (actions) were uploaded and distributed among seven strategic goals. Most of these proposals have been openly discussed and voted by 204 registered users. With this exercise, the expectations and demands of the university community were taken into account, and 65% of them have been incorporated into the final version of the strategic plan. This has created a more consensual strategic framework and also increased the stakeholders’ commitment to the university goals and a sense of organizational unity. The success of the initiative was demonstrated by the wide consensus shown by the university senate: 52 votes for, 0 against and 2 blank.

The open government philosophy has been also applied to the annual monitoring of the strategic plan. In the follow-up report for the first year of the strategic plan implementation, 91 actions have been openly assessed by the university community through the online platform, receiving 825 votes and obtained an average score of 3.5 out of 5. In addition to these results, it is necessary to highlight the change of role of the university community, moving from a mere spectator to an active agent of the development of the strategic plan, as a main result derived from this initiative. The method followed in the participatory process of drawing up the strategic plan promotes the strengthening of the feeling of belonging to the university community and the alignment with the objectives defined in the plan.

In the implementation phase of the plan, transversal working groups around strategic lines or defined actions were established, in which people from different areas, services and levels voluntarily participated. In this way, the rigidity of the hierarchical boundaries, which supposes a brake on innovation and an obstacle to the efficient fulfillment of institutional purposes, could be dispelled.

From the in-depth interviews conducted on a sample of university director board, we find some consensus regarding the key drivers in such strategic planning process. In particular, the strategic plan must be assumed by the entire community, for which the participation and involvement of the stakeholders is crucial. This idea is aligned with Naidoo and Wu [

42], who argue that an organization must bring on key board members to commit to the project and achieve strategic objectives. The strategic plan must have a simple structure, be clear and concise, so that it is easily communicable and intelligible. Once the strategy has been formulated, managers need to translate it into clearly communicable objectives and measures for all actions. From there, it is linked to the objectives related to the critical processes and, ultimately, to the people, technology, organizational climate and culture necessary for the execution of successful strategies [

43]. The monitoring of the strategic plan facilitates the continuous reassessment and accountability to society. As Wakim and Bushnell [

44] argue, monitoring and measurement through indicators that respond directly to strategic objectives is essential. On the other hand, strategic objectives must be economically feasible as otherwise they would become a utopia leading to frustration. However, most of the interviewees assume a higher level of demand with fewer resources [

45]. Moreover, the principles of open government (collaboration, participation and transparency) generate new work dynamics in higher education institutions, turning universities into a social agent. According to Ramírez-Alujas [

1], government and public services must be open to public scrutiny and to the supervision of society (transparency). Thus, spaces for dialogue, participation and open to the necessary collaboration have to be established to find better solutions to public problems. In this sense, and in the field of higher education institutions, Boyko [

46] points out that the university governing board have the challenge of functioning as a link between all institutional levels such as university, faculties and departments, and thus, be able to achieve the principles of open government.

At the same time, the main causes hindering the optimal deployment of the strategic direction have been detected based on the in-depth interviews and the historical experience of the university in previous strategic plans.

Namely, the low applicability and execution of previously designed strategic plans literally expressed by several interviewees as

“the main problem is that we do not have an information system for management, that is, we do not have historical indicators or seed values that serve as a reference for setting future objective values”; skepticism about its utility and feasibility in the context of the crisis, expressed as

“with the current situation we have, nobody believes. We cannot foresee what will happen next year and if there is going to be money or if the budget is going to fall … and without these forecasts we cannot create”; the lack of economic, material and human resources that make it possible the fulfillment of strategic plan. At this point, Combs et al. [

47] highlight that resources are really strategic when they are able to generate sustainable competitive advantages over time; the failure in the dissemination and communication of the strategic plan in order to raise awareness of the entire university community; the lack of maintenance over time of the general strategic objectives, motivated by changes in the governing board at the university, expressed as

“the strategy of a higher education institution must be long-term. However, the strategic plans are usually linked to rector’s mandates. Thus, a new rector enters and does not finish the previous projects because he/she wants to do something different. This leads to a constant drift”.

These results connect with [

48], where the main causes that make strategies and plans fail are a bad execution, the lack of understanding of the future and sometimes of the present, and the lack of consideration of the sources of uncertainty outside the strategy or plan itself.

5. Conclusions

In this work a web platform has been developed with the aim of promoting the participation and collaboration of all university’s stakeholders in the design and follow up of the strategic plan. The introduction of such technological innovation provides with a much more sustainable strategic planning process within the university because it promotes open discussion, participation, reflection and learning. Moreover, the principles of open government encourage a new collaborative workflow and the identification of stakeholders with the corporate goals, thereby enhancing their commitment to the fulfillment of the strategic plan.

Following the phases of the public policy cycle of the LUDO model, the initiative carried out in this work was firstly designed. For this purpose, the main tasks have been to discuss, write proposals and to design solutions. To do this, through the platform of consultation and open participation all members of the university community and citizens have freely formulated their proposals, as well as have assessed and commented on the proposals put forward by other people. Thus, a public debate has been opened on the design of the strategic planning of the university, at the same time that concrete proposals have been collected on the actions to be developed, written directly by the university community itself and the citizenship.

In this way it has been possible to design solutions that have allowed to achieve the strategic objectives in a collaborative way, involving and strengthening the commitment of the university community. In addition to the comments to the published proposals, the platform has also allowed suggestions on the participatory process, so that the initiative can be improved in the design of the next strategic plan of the University.

Results reported show the successful pilot experience launched in the university, which received around one hundred online proposals, all of them monitored and evaluated by the whole university community with a grade of 3.5 out of 5. The strategic plan is then considered a useful instrument for the management of higher education institutions, especially in contexts of uncertainty. The internalization of the strategic objectives by the entire university community and their commitment to achieve them, depends on their degree of participation and involvement in the strategic planning process. One of the mistakes discovered thanks to the historical experience in previous strategic plans of the reference university, is to consider the strategic plan as an objective itself, rather than an essential process to bring the institution to fruition. On the other hand, the implementation and monitoring depends ultimately on the university board of directors, as their experience, motivation and institutional commitment contribute to the success of the strategic management, creating competitive advantages for the university. As future works, the knowledge acquired with this initiative will be transferred to co-create other important documents in the university such as legislation to regulate the teaching and research activity of professors and management activity of the public managers.