Abstract

The debate on overtourism still lacks conceptual precision in its delineation of the constituent elements and processes. In particular, conflict theory is rarely adopted, even though the social conflict is inscribed into the nature of this phenomenon. This article aims to frame the discussion about (over)tourism within the perspective of social conflict theory by adopting the conflict deconstructing methods in order to diagnose the constructs and intensity of disputes associated with overtourism. In pursuit of this aim, the study addresses the following two research questions: (1) To what extent has the heuristic power of the conflict theory been used in overtourism discourse? and (2) How can overtourism be measured by the nature of the social conflicts referring to urban tourism development? The systematic literature review was conducted to analyze research developments on social conflicts within the overtourism discourse. In the empirical section (the case studies of the Polish cities, Krakow and Poznan), we deconstruct the social conflicts into five functional causes (i.e., values, relationship, data, structural, and interests) to diagnose the nature of the conflicts with respect to urban tourism development. This study shows that value conflicts impact most intensively on the nature and dynamics of the conflicts related to overtourism.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the contemporary discussion on the negative effects of tourism development in cities has unfolded under the label of overtourism, stemming from an increasing and uncontrolled tourists’ flow concentration in urban centers [1,2,3]. The phenomenon is characterized primarily in a social context as there are, most of all, the residents who “suffer the consequences of temporary and seasonal tourism peaks, which have enforced permanent changes to their lifestyles, access to amenities and general well-being” [4]. Despite the discussion of whether or not the overtourism syndrome is new and limited to a few destinations and urban centers [1,2,5,6], many experts indicate the occurrence of open social conflicts. It seems to be the most characteristic constituent and manifestation of overtourism [7,8,9]. As Goodwin [3] noted, in circumstances of unacceptable deterioration of residents’ quality of life (and also visitors’ experiences) in the area, they take measures against it. In addition, the dynamic course of conflicts, their political overtones, and global media coverage are stressed [10,11]. This is why overtourism (or at least its “social landscape”) is associated synonymously with such terms as tourismphobia [12] and anti-tourism [13].

The problem is crucial as the danger for destinations affected by overtourism can lead to the creation of a protracted social conflict [14], fostered by changing actors and the lack of a clear beginning and end. Thus, responsible urban tourism governance requires the ability to diagnose the conflict and conflict management [15,16] and work out the tailored-made solutions for managing overtourism. However, the nature of overtourism is complex, and its causes, range, and intensity are always conditioned by the local context [2,8,9]. Therefore, despite the efforts in [17], the literature lacks universal and commonly agreed methods and tools for measuring the phenomenon, while it is easier to propose techniques for limiting or preventing its development [18,19]. Therefore, even if the debate on overtourism seems to be exploited and even overused, it still lacks conceptual precision in its delineation of constituent elements and processes [1,2]. In this context, focusing on social tensions and the conflicts related thereto, overtourism opens avenues to reach the core of the phenomenon and also to learn about the most important and burning issues arising from it. As an indispensable part of social life, conflicts emanate errors or side effects of changes taking place in cities, calling for the need for corrections [9,15,20,21,22,23]. Therefore, by recognizing the cause and nature of social conflicts arising in cities potentially or actually affected by overtourism, one can explore the characteristics of the phenomenon itself profoundly.

This article aims to frame the overtourism discussion into the social conflict theory by adopting conflict deconstructing methods in order to diagnose the constructs and intensity of disputes associated with overtourism. Hence, we answer Kreiner’s, Shmueli’s, and Ben Gal’s [24] call who state that tourism literature is “in need of a systematic theory of conflict in tourism that addresses factors such as the nature of the conflict, conflict management, conflict resolution, and conflict mitigation”. In pursuit of this aim, this study addresses the following two research questions: (1) To what extent has the heuristic power of the conflict theory been used in overtourism discourse, including the delineation of social conflict types? and (2) How can the state and intensity of overtourism be measured by the nature of social conflicts referring to urban tourism development?

Thus, we have conducted a review of the extant literature on tourism to recognize the relationships between tourism development and conflict theory, as well as identify approaches, strategies, and tools developed to address overtourism issues. In the empirical section, we apply the multidimensional Circle of Conflict (CC) model, adapted from Moore [25], to diagnose the disputes related to urban tourism development. As overtourism is a particular city context-dependent phenomenon, we adopt the case study method by conducting field research in two Polish cities to verify the model, i.e., in Krakow and Poznan.

We contribute to a better understanding of the overtourism development mechanism and its management by including the social conflict theory in the discussion. We also propose and verify a method and tool for diagnosing the potential and actual disputes related to overtourism, assuming that overtourism is a social phenomenon, and thus it manifests through social conflicts. According to the findings, the presence of the phenomenon could be identified by studying the structure of the social conflicts related to it. Thus, the deconstruction of functional sources of conflicts expand the knowledge of the overtourism development process.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: First, the Materials and Methods Section is introduced. Next, the Systematic Literature Review Section presents a literature review, starting with the nature of social conflicts, then analyzing the conflict approaches in urban tourism development studies and focusing on strategies and tools used to manage the excessive tourism in cities. On the basis of the conclusions resulting from the theory, the local contexts and the findings of the study are presented, divided into two sections, the Krakow section and the Poznan section. The Discussion and Conclusions Section confront the findings with the existing literature. Finally, the contributions of this study are highlighted, as well as limitations of the study and roads for further research.

2. Materials and Methods

The study applied both secondary and primary sources of information and data. In order to address the question, “To what extent the heuristic power of the conflict theory has been used in overtourism discourse (including the delineation of social conflict types)?”, the traditional selection of narrative literature was conducted, focusing on such areas as social conflicts, tourism development, and overtourism.

To present the developed research paths on social conflicts within overtourism discourse, a systematic literature review was applied. Two scientific databases were used, Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) and Scopus (Elsevier). The bases were chosen because of the vast number of confirmed high-quality journals [26]. The research included only scientific articles indexed in both databases, dated on 14 November 2019. The procedure consisted of the following steps: First, the search terms were selected and included “overtourism and conflict*”, “overtourism and protest*”, and “overtourism and dispute*”. Secondly, to assess a volume of available studies, an initial scanning was conducted, accessing the Web of Science and Scopus databases. As a result, 24 records were yielded, which included at least one of the mentioned research phrases in the title, abstract, or keywords. After sieving the material and removing duplicates, 11 papers were considered for detailed content analysis (for the listing see Appendix A). The analysis focused mainly on recognizing the conflicts’ triggers and tools incorporated to address the particular matters. The retrieved works presented both empirical and theoretical articles, released from 2017 to 2019. The 11 core studies were also complemented by other studies relevant to the research problem, which were selected arbitrarily by the authors.

For the empirical layer of the study, the Moore’s [25] Circle of Conflict model was applied as the conceptual framework. The model is rooted in the conflict orientation perspective, which recognizes the perspectives the conflict parties identify and understands the issues and objectives of the conflict, and places these issues within the context of the conflict. According to the author, the model has a universal nature and can be adapted to every type of conflict situation and intervention level. In the tourism field, the model was used for the deconstruction of conflicts in the process of spatial planning for tourism in Troia-Melides Coast, Portugal [27], and for the assessment of key actors’ predispositions in urban tourism systems for managing the mediation process within conflicts caused by overtourism [16].

According to the model, the conflicts are usually caused by many coinciding factors. Only a few of them relate to the main problem domain. However, the characteristic feature of every type of collective conflicts is their reference to universal aspects of interpersonal relationships. Thus, it is crucial to identify them and adopt appropriate methods and tools of intervention. The model identifies the following components of universal conflict dimensions [25]: values, relationship, data, structural matters, and interests. As it is impossible to weigh their importance (only their intensity could be assessed) or study them separately, in the model they are presented as a circle of conflict (see Figure 1). Moore claims that a conceptual or “conflict map” is needed to work effectively on conflicts. Such a conflict map details why the conflict occurs, identifies barriers to settlement, and indicates procedures to manage or resolve the dispute. That is why the recognition of parties’ attitudes, relationships between them, shared and opposite values, the extent to which they can access and interpret information, their interests, and structural conditions of conflicts is more important than the recognition of the actual merits behind them. Nevertheless, convergences and discrepancies between all the causes are significant. The model can be applied to diagnose the conflicts, and also to propose intervention tasks according to the identified conflict cause types.

Figure 1.

The Circle of Conflicts in the tourism context, adapted from Moore [25].

To verify the Circle of Conflict model [25] as a method for diagnosing and deconstructing disputes associated with overtourism, we used a two case-based approach. The case study method lets a researcher explain the rich context of the studied phenomenon and create analytical generalization [28,29]. We decided to research two Polish cities, Krakow and Poznan, which are similar in population potential, but at the same time they differ in the context of tourism potential. Thus, the cities were chosen on the basis of the following three criteria: (1) the size of the city, (2) connectivity, and (3) the tourism potential (see Table 1). Both cities are major metro areas of comparable size of more than one million inhabitants. The differences in other spheres are significant. The connectivity and tourism indicators are 3.5 times higher in Krakow than in Poznan. Moreover, the review of public reports, official documents, local press, and electronic media allowed us to evaluate the extent of overtourism issues experienced in both cities. In Krakow, the dispute related to overcrowding and tourismification of historical areas was manifested as a public issue; meanwhile, in Poznan, overtourism was discussed as a potential threat. We argue that these different overtourism development stages are the rationale base for verifying the proposed method.

Table 1.

Selected statistics for metropolitan areas of Krakow and Poznan.

In each city the representatives of the key institutions involved in tourism planning and management were interviewed, using the structured interview method [35]. The researchers in both cities used the same instruction to follow the logic of questions. The interviews were conducted with the representatives (managing directors or public officials) of key entities (public, private, and non-profit) engaged in a tourism destination. At first, the informants were selected purposefully based on the knowledge of the researchers of tourism governance in both cities. Additionally, the snowball method was applied to yield the samples.

In the interview guideline, there were two questions that referred to overtourism and five questions that discussed the nature and dynamics of conflicts concerning tourism development in each city (see Appendix B). The core of the interview was the informants’ assessment of the causative element of the conflicts they recognized, as Furlong [36] notes, “managing conflict effectively is a simple two-step process that starts with how we assess the conflict we are facing, followed by what action (or inaction) we decide to take to address it”. The informants were asked to rate (with a five-grade scale, where 1 referred to the lowest intensity and 5 referred to the highest intensity), and then justify or discuss the intensity of each causative factor of disputes forming five universal conflict meta-categories (dimensions), i.e., values, relationship, data, structural matters, and interests. The factors and their characteristics were derived from the CC model [25]. Due to the complex nature of overtourism and the number of factors forming meta-categories (16 in total), the grade element was applied to structuralize the interviews and to help the informants relate each assessment to other answers. As the CC model does not impose the form of measurement, the grading is a rarely used technique [16,25]. Most researchers focused on open questions, limiting the number of the discussed issues [27].

In addition to the main questions, the researchers were provided with ancillary options for refining the respective topics. The informants were able to assess the intensity of occurrence of conflict causes, according to the meta-categories (dimensions) of the CC model [25]. Additionally, two questions about the informants’ organizational affiliation were used for coding purposes. In the interview guideline, we used open questions and rating questions; however, the interview consisted mainly of the informants’ comments. For the interview design template, see Appendix B.

The research was carried in two rounds as follows: March to April 2018 in Krakow, and May to June 2019 in Poznan. Eventually, we conducted 15 interviews in total (given by 19 informants in total), including 6 in Krakow and 9 in Poznan. The most extended interview lasted 80 min and the shortest one 31 min. On collating the results, we conducted the descriptive and substantive content analysis. Two researchers read every interview. Given the low number of interviews and the nature of the problem and the need for generalization, the use of advanced methods of data analysis appeared to be unjustified.

3. Systematic Literature Study

3.1. Social Conflict: Theoretical Perspectives and Applications

Conflict is a term popularly used in contemporary colloquial, journalistic, and scientific language. The systematic studies started in the 1950s and led, among other things, to the rise of the science of conflict [37]. Taking into account the disciplines for which conflict is an essential issue, Adamus-Matuszyńska [38] listed the following research perspectives and approaches to this issue: (1) psychological perspective (including psychodynamic concepts); (2) psychosocial approach (from Georg Simmel’s considerations, through Morton Deutsch’s studies, to Axel Honneth’s thoughts); (3) sociological perspective, developed in the 1950s in response to Talcott Parsons’ functionalism (i.e., the works by Lewis Coser and Ralf Dahrendorf which are still the dominant paradigms in sociology); (4) political approach (socio-political, with John Burton and Johan Galtung as representatives); (5) economic approach (Kenneth E. Boulding); and (6) ecological approach.

As Boulding [39] and Coleman [40] point out, the complexity and multidimensionality of conflicts require an interdisciplinary approach to analyze the causes of conflict and the possibilities of resolving it. However, as Druckman notes [41], such an approach is associated with controversies. The result varies, among others, from the relationship between a basic and an applied research (or the theory and practice), the presence, since Wittgenstein–Popper dispute, of an epistemological dilemma, between a positivist and constructivist attitude towards knowledge, or a methodological dilemma.

Still, the most popular approaches to social conflict and also in tourism studies (see [15,27,42,43]) evoke Simmel’s, Marx’s, or Dahrendorf’s approaches, and especially Lewis A. Coser’s [44] framework [38]. According to the latter approach [44], conflict-generating mechanisms refer to access to power and resources in a structured society. Thus, conflict does not always have to cause social change, and the play between entities does not always have a zero-sum response, which means that a victory of one entity does not always take place to the detriment of the other. Therefore, two kinds of social conflict can be distinguished, internal and external. The former concerns purposes, values, and interests. If it does not concern the foundations of local social relationships, it is positively functional for the structure of society (it rectifies problems associated with the system of power or an axio-normative system). The conflict reaching the fundamental values of a specific group carries a severe risk of destroying it. External conflicts are associated with the external enemy mechanism directed towards another group, i.e., a majority group can be perceived as hostile to goals, needs, and aims of minority groups. The presence of the enemy is perceived as a reason for power to defend a group’s values and interests. Coser [44] also distinguishes between non-realistic and realistic conflict. The former, the stimulated one, aims at releasing tension and preserving the structure of a group rather than producing specific results. The latter derives from a situation in which failing to meet the specific needs brings about frustration with an objective and a real source. In Coser’s view, social conflict creates various associations and coalitions, which, in effect, provide a structure for a broader social environment.

As far as the tourism studies perspective is considered, the most important recent founders of social conflict conceptualization should also be showcased as follows:

- Burton’s [45] approach, which distinguishes contradiction and social conflict; with that, the former refers to the natural social situation, and the latter is associated with the inability to meet human needs (which is destructive to all, i.e., the individual, property, and systems);

- Horowitz’s [46] approach, which focuses on ethnic conflict, interpreting this conflict as a lack of understanding of symbols and values by two or more parties;

- Honneth’s [47] approach, which, among other things, opposes against approaching conflicts to differences of interest. According to Honneth, the essence of social conflict lies not in the struggle for social equality but the struggle for recognition. The approach takes into account the sense of the subjectivity of the individual (or social group) as causes and dynamics of conflicts, i.e., psychological (identity) aspects, moral (respect) issues, and interactions.

As already mentioned, there is a need, among modern conflict researchers, to apply an interdisciplinary approach in the conflict analysis process (see [38]). As Honneth [47] argues, interpreting conflict only in a political perspective or as concerning economic redistribution is short-term oriented as it does not reach the “moral grammar of social conflicts”. As Furlong [36] stresses, it is not possible to resolve the conflict effectively without having an ability to translate conflict theory into models and tools that help to diagnose the specific conflict correctly and choose the suitable, tailor-made actions and effective interventions.

3.2. Social Conflicts in Tourism

The studies on social conflicts have gained increasing attention among researchers representing tourism studies (e.g., [15,24,42,48,49,50]). The conflict issue has been explored in different perspectives (e.g., cultural, economic, or political [51,52]) usually employing qualitative research methods [24,42]. Tourism researchers propose several additional dimensions referring to conflict within the tourism contexts. These include tourism and cultural conflict [51,53,54], tourism development conflict [49,55], environmental and functional conflict [56] and, last but not least, social conflict [42,57], referring directly to Coser’s [44] concept.

By analyzing the genesis of conflicts in tourism space, Kowalczyk-Anioł and Włodarczyk [15] investigated its inevitability, the ambivalent nature of conflicts. They also identified the functions of conflicts in the perspective of local development, for example, whistleblowing (i.e., warnings and information signaling tourism disfunctions), stimulating (stimulating the search for innovative solutions), diagnostic (exposing weaknesses and problems of the local system, as well as revealing differences and interest groups), and integrative (involvement against something). Referring to context-specific conflicts within the tourism development perspective and based on a literature review, Colomb and Novy [50] explored the context of contemporary urban tourism conflicts. Applying the grounded theory, Kreiner et al. [24] proposed a systematic conceptual understanding of the conflicts surrounding the development of religious-tourism sites. The authors stated that disputes revolve around the conflicting interests, values, and goals espoused by different stakeholders; by ethnic communities and outside developers (over the economic benefits of tourism); and by tourists and locals (over limited resources). Thus, three “super-frames” of the conflicting parties’ perception of the destination can be distinguished, i.e., issues (physical and spatial), procedure or process, and value-influenced function. High-intensity conflicts involve deviation within all three super-frames, and lower intensity conflicts typically involve deviation in only one or two super-frames, or possibly low-intensity deviation in all three [24].

As far as the specific real conflicts are concerned, the so-called “Chinese tourists’ wave” in Hong Kong has been relatively the most explored conflict in the tourist literature [58,59,60,61]. Tsaur et al. [60] conceptualized tourist-resident conflict and developed a scale for assessing this particular conflict type on the basis of the relationship between Hong Kong residents and tourists from mainland China. The authors claimed that from the perspective of residents, every tourism conflict can be perceived in terms of cultural, social, and resource/transactional issues. Within the cultural conflict, besides the traditionally indicated elements such as the commercialization of the host culture, the use of natural and cultural resources, and the degree of economic dependence of the destination community [51], it is crucial to understand the interactive influence of tourist stereotypes and the attribution process of residents’ encounters with tourists [62]. The resource/transactional conflict refers to physical space conflicts that result from residents’ physical space (e.g., leisure facilities and public transportation) being occupied by visitors [60,61]. The concept of urban hypertrophy of tourism conceptualized by Kowalczyk-Anioł [63] refers indirectly to the resource conflict.

In summary, although the social conflict issues have been gaining attention in the tourism studies, the need to deepen the studies on the theory of social conflict in a tourism context is still apparent, as stressed by Yang et al. [42] and Kreiner et al. [24]. In particular, since the first instance of overtourism as a (new) urban issue, the death of the comprehensive analysis of understanding and managing conflicts has been even more noticeable. That is why, in the next section, we identify the main research paths of overtourism, i.e., conflict scientific literature review.

3.3. Social Conflicts in Overtourism: Causes, Approaches, and Applied Tools

As cities have grown progressively to the leading tourism destinations [64,65,66], the tourism industry has become more and more integrated into local economic structures [67,68]. This effect has escalated in cities, which have incorporated tourism as a tool for economic development or renewal [69,70]. However, for a long time, tourism has been promoted as a tool to enhance the community’s quality of life [71,72,73] mainly owing to the sector’s interdisciplinary character, seemingly beneficial outcomes for a wide range of stakeholders, and a multiplier effect [74,75]. The constant development, liberalism, and boosterism, supported by associated optimism have been the dominant logic within the industry and among its advocates [76,77,78]. The overtourism phenomenon currently observed, particularly in European cities, is the harmful consequence of these policies to the sector’s evolution [16,69,79,80,81,82,83].

Regardless of whether overtourism is a buzzword, it has evolved, with the considerable role of new mechanisms of knowledge production (cf. [84]), from a news-media popular term to a comprehensive, but also blurring, relational, and stigmatizing concept [77,85]. Many researchers [1,2,3] stress that the problem behind it is not new. The concept of the vicious circle of tourism development in heritage cities was proposed by Russo [86] and is an antecedent study of overtourism. According to many researchers, it is rooted in the global discussion on the limits of growth, dating back to the 1970s (Club of Rome’s report [87]), as well as the concerns and theoretical discourses surrounding the idea of sustainable development and resilience, which have been discussed both in the context of tourism and in general [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96], and later in the strict overtourism context [77,83,97,98,99]. Hall [98] claimed that the debate on this phenomenon is (and should be) an inseparable part of the global discussion on the limits of growth. Nevertheless, one can limit the overtourism syndrome to visitors’ volume and discuss it within the tourism seasonality concept [100,101,102,103]. In this context, overcrowding and disturbances caused by an excessive tourist traffic are the extreme manifestations of the so-called high season and ineffective or even incompetent destination management [1,2], consequently challenging the destination’s economic sustainable development [102] and its social resilience [103].

In the conditions of overtourism, the interdisciplinary character of tourism that is usually perceived as a strength acts, on the other hand, as a weakness. The infrastructure necessary to run a tourism business is highly interrelated and shared with the infrastructure use daily by locals in cities, for example, public transport, restaurants, points of interest, shopping centers, train stations, and airports [7,104]. In this regard, urban tourism can quickly be taken for either a conflict trigger or a context, given that frequent protests against tourism are nested deeper in a broader urban change and social issues [78], such as city rights, cost of living, housing affordability [4,105], corporate developments that are deemed to damage the fabric of local communities, and exclusion of precarious groups [9]. On the basis of the conducted systematic literature review, Table 2 exhibits the types of disadvantageous overtourism effects identified, until now, in cities.

Table 2.

Disadvantageous consequences of overtourism.

One of the underlying conditions to enable tourism development in a destination is the local community acceptance [108,109]. The residents’ attitude is often based on objections or refusal towards further growth, manifested through social movements’ activity [21,70,77,110]. This situation indicates a rise in real conflicts and calls for integrated management procedures [74,104]. The works selected for our study build upon the following four concepts: economic growth, sustainable development, power, and conflict management (Table 3).

Table 3.

Conflicts around overtourism: approaches and tools applied.

The majority of the analyzed papers relate the social conflicts to the notion of economic growth. The studies associate the problem’s origin with the neoliberal boosterism model [78]. According to them, urban policymakers have, in many cases, introduced tourism into local economic development plans or adopted it as an urban renewal tool without proper planning [9]. Tourism is also perceived as a popular and easy tool to promote economic activity, which needs neither much public investment nor control to bear the fruits [21,78]. Such misconduct based on the maximization strategies has resulted in adverse impacts on the residents’ quality of life [105]. The detrimental effects include [9,21,77,78,105]: gentrification or tourismification of the cities, heritagization, proliferation of the private tourist rentals (short-term rentals and Airbnb facilities, influencing the housing market), structural changes in local commerce and the urban network (e.g., high dependence on the hospitality services), congestion, overcrowding, oversaturation and overexploitation, environmental changes, pollution and waste generation, producing or deepening social inequalities, violation of fundamental laws, privatization of public spaces and services, commercialization of the city, safety issues, and tourists’ improper and invasive behavior (for a more detailed list of the consequences see Table 2). The adverse outcomes appear to undermine the existing economic paradigm and entail the tension between growth and degrowth [4,105].

The studies analyzed also reveal that there are two explicit social unrests’ triggers, i.e., overcrowding and night-time entertainment connected with the so-called “party-tourism” [4,21,105]. With this in view, the industry with the local authorities have put forward the institution of Night Mayor, for example, in Budapest [21], and the academia elaborated the tourism activity optimization [105]. Oklevik, Gössling, Hall, Jacobsen, Grøtte, and McCabe [105] proposed the theoretical model of optimization to handle the overcrowding issue, based on the data retrieved from Norwegian destinations. The underlying assumption of the strategy is to increase profits and the value gained from maintaining or decreasing the numbers of arrivals. This aim should be achieved by extending visitors’ length of stay and incrementing the local government revenue by imposing a departure tax. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that the suggested solution requires further development.

In the sustainable development concept, (Table 3, row 3) the interest concentrates mainly on a community’s long-term well-being (embracing three dimensions, i.e., economic, social, and environmental), rather than on financial gains and market mechanism of sustaining the constant economic growth [7]. This research path focuses on determining the residents’ perceptions and acceptance of tourism and tourist activity and its impact on the local environment, as well as on attempting to determine the destination’s carrying capacity which limits the tourism development without producing adverse outcomes [107]. The main factors playing roles in the conflicts’ upsurge, which are mentioned in the relevant reviewed papers, include gentrification or tourismification, heritagization, proliferation of the private tourist rental (short-term rentals, Airbnb), congestion, overcrowding, oversaturation and overexploitation, environmental changes, pollution and waste generation, and tourists’ improper and invasive behavior [7,99,107].

From this approach, Postma and Schmuecker [7] developed a conceptual model to define conflict drivers and irritation factors between residents and visitors. The framework’s building blocks constitute visitors and their attributes, residents and their attributes, conflict mechanisms, areas of conflict between both parties, and indicators of quality and quantity of tourist facilities. A study of the accommodation situation in Hamburg against the overtourism background, identified the following two focal conflict mechanisms: (1) cultural distance (cultural differences between tourists and locals), and (2) spatial and temporal distribution (the number of tourists gathered in space or time, overcrowding occurring this way can cause irritation irrespective of “cultural distance”). However, the authors recommend conducting more in-depth research to refine the model.

The carrying capacity concept [91,111] is another method implemented to scrutinize the tourism-related conflicts at a destination. The carrying capacity term refers to a numerical threshold of visitors received in a particular area, the exceeding of which results in the social and cultural changes the local community no longer accepts [99,107]. On the one hand, Namberger and others [107] investigated Munich residents’ opinions in terms of the social carrying capacity and the overcrowding in the city. The study revealed two triggers of local contentions ignited by tourism from the perspective of the inhabitants, “crowds of tourists” and “disturbances by smaller groups of tourists” (e.g., from different cultures). These findings converge partially with the research carried out by Postma and Schmuecker [7]. On the other hand, Cheung and Li [99] revised the physical carrying capacity in Hong Kong. The researchers incorporated the notion of hysteresis (the irreversible impact) in the tourism field. They proved that uncontrolled and immediate growth of the same-day visitors’ number at a destination, in the long run, negatively and permanently impacts the visitor and resident relations, regardless of further introduction of crisis management or neutralization of the conflict’s antecedents. Nevertheless, similar to the previous cases, further analyses are necessary to draw more general conditions in which the hysteresis can take place as a result of overtourism.

Overtourism-induced conflicts have also been studied through the lens of social power theory (Table 3, row 4) [12,106]. In this context, the relation between social policy and the tourism policy is considered, with reference to neoliberalism. Briefly, tourism is perceived as a tool of exerting power by the governmental bodies and the prime benefit to the quality of the residents’ life [12]. Similar to the economic growth case, the range of social conflicts’ antecedents include all of the nine identified triggers (see Table 2 and Table 3). However, this issue emanates mainly through the “right to the city” discourse [112], where the social circles struggle to maintain or win back the public space and put the public value first, contrary to the market-oriented strategies [106]. Considering the city of Barcelona as an example, Milano [12] indicated the failure of the following methods applied by the local governments to alleviate these kinds of local disputes: de-seasonalization, decongestion, decentralization, diversification, and deluxe tourism. These strategies are based mainly on the quantitative adjustments, which do not address the qualitative drivers of overtourism (e.g., structural changes in local commerce and the urban network). However, there are also rare cases when city authorities intervened in the proliferation of private tourist rentals by introducing policy adjustments. In Palma de Mallorca, Amsterdam, Madrid, and Barcelona partial or total restrictions on the licensing of tourist accommodation were imposed [12]. The research also illustrated the extreme means of handling the public protests, such as in the case of Anti-Meeting Law in Sevilla, which violated fundamental laws to assembly and the freedom of speech. To maintain a tourism-friendly image and provide safety, the municipal government banned, among others, the social gatherings and the street art practices in the public spaces [106].

Finally, the conflict management (CM) emerging from the organizational conflict theory is the last concept applied for analyzing the social conflicts around excessive tourism in cities (Table 3, row 5). This approach proposes a tool for deconstructing such conflicts by recognizing their complex functional structures within urban conditions. It also allows us to determine what the conflict causes are, what activities form the process of the CM, and who should initiate and carry it out. Moreover, the tool is useful to identify the structure of conflicts at various stages of their development (including potential conflicts) and the level of overtourism development (including the pre-overtourism and the mature-overtourism stage).

3.4. Conclusions

Although the researchers analyzing the nature of the conflicts within the tourism context refer mainly to the fruitful achievements of the social studies in this area, relatively few studies apply the specific conceptual frameworks for deconstructing the conflict structure and dynamics. The majority of studies focus on identifying the causes and substantial subjects of conflicts due to the proposed solutions related to the specific conditions of tourism development in the destinations. Otherwise, two studies refer to more universal concepts. Kreiner at al. [24] identified interests, procedure and process, and values as “super-frames” of the conflicts between stakeholders due to the measuring of their intensity extent. Tsaur et al. [60] recognized the cultural, social, and resource/transactional dimensions of the conflict between residents and visitors.

As far as the studies on overtourism relating to conflicts are concerned, the contemporary discussion seems to offer a somewhat limited understanding of methods and tools referring directly to the deconstruction of the conflicts related to the excessive growth of tourism or their mitigating (see Table 3). Nevertheless, the studies which address the conflict issue can be grouped into those which refer to the substantial subject of disputes and those which refer to the nature of conflicts itself. In the former group, there is no shortage of studies which analyze the causes of the conflicts and suggest adequate solutions in the form of imposing new policies towards tourism development, public interventions, adjustments in measuring tourism impact and visitor management, changing the governance structure, or verifying the marketing strategies [12,21,99,105,106,107]. In all these studies, the researchers stress the scarcity of the data characterizing the core of the conflicts as the significant challenge in mitigating them.

The researchers representing the latter group of studies [7,16] tried to abstract from the specific context of tourism development in studied destinations and identify the universal factors and mechanism behind the overtourism-related conflicts. Regardless of the core of the conflicts, their structure and dynamics are driven by interrelated powers whose nature is universal for every dispute. Postma and Schmucker [7] identifed cultural distance and spatial and temporal distribution as the elements of the mechanism of formation of the concrete conflicts. Zmyślony and Kowalczyk-Anioł [16] recognized conflicting values, interests, relationships, data, and structural matters as the causes of the conflicts. This model is also in line with Kreiner et al.’s [24] approach. What is essential, both studies propose the empirical frameworks that could be applied to other destinations affected by the overtourism syndrome. However, considering difficulties in obtaining reliable information measuring both the scale of overtourism and the extent of the related conflicts, only the Circle of Conflict model used in the last-mentioned study could be verified as the method of diagnosing the intensity and nature of the disputes associated with overtourism.

4. Results of the Empirical Verification

4.1. The Conflict Situation in Krakow

Krakow, included in the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1978, belongs to the most prominent tourist destinations in Central and Eastern Europe. The city has also grown into a flagship travel destination in Poland, and the second-most populous urban area, inhabited by 0.76 mn residents. In 2019, Krakow received 14 million visitors, out of whom 10.15 million were tourists (among them 30% foreigners, mainly the Europeans) [113]. The role of tourism in the local economy has been increasing, and the sector contributed 8% to local GDP, generating 10% of the available workplaces in 2018 [114].

Over the last decade, the steadily booming inbound of visitor flows have concentrated in the historic city center, The Old Town Quarter. Consequently, the area has started undergoing the tourismification, gentrification [115], and commodification processes. These have incited a discussion on the ongoing center’s depopulation, disturbances caused by the constant city users’ and tourists’ circulation, and the night-time economy, both in the local media [116,117,118] and among academics [16,114,115,119]. Although the issues have been addressed in the city’s latest strategic documents [113,120], the operationalization of the general action frameworks remains the burning question. In 2011, Mika [121] identified the tourism-related conflict factors by stressing the Old Town’s multifunctional character and the ensuing differences in the ways it is used, especially the conflict between the tourist and residential functions, overcrowding during the peak season, and contradictions among various forms of tourist traffic. Moreover, the short-term rentals’ expansion [122] and popularization of the amenities for low-budget entertainment tourism [123] have exacerbated the situation. As a result, the touristic pressure on housing resources [124], in particular those due to the tourist rentals proliferation via the Internet platforms (such as Airbnb), impacts the entire Old Town Quarter and the adjacent areas, such as Podgórze [120]. All these changes have led to the conclusion that the city has evolved from a mature to an overtourism destination. This opinion is supported both by the academic voices [16,114,115,125] and the ongoing public debate, with the local authorities’ active participation [122,126,127].

For the purpose of the research, the following ten informants representing six key stakeholders were interviewed: the local chamber of tourism, the residents’ social movement, the public city tourism administration, the city council as a policy-maker body, a regional tourism organization, and the destination service providers.

Almost all the informants perceived overtourism as a significant problem of the urban development. In detail, the most significant issues listed were the following: spatial concentration of tourist activities and a progressive change in the structure of services and retail in the city center; noise and other arduousness associated with the night-time entertainment; the depopulated but crowded city center; growth of the grey tourist market; problems on the housing market (boosting short-term rental accommodation, growth of buy-to-rent offers, increase in rental rents, and real estate prices, residential gentrification); and progressive loss of the city atmosphere. However, the informants stressed that such a significant linkage between these issues and the uncontrolled tourism growth, especially in the city center and other tourist spots, was perceived in terms of the overtourism problem. The majority of them assessed its intensity as high, and two assessed it as moderate. Only the representative of the local tourist chamber stressed that the problem was not as acute as the local media reported. However, none of the informants could provide the detailed data confirming the extent of the phenomenon, they claimed they relied on the knowledge of experts and the media reports (at the time of the interviews the study conducted by Szromek and others [114]).

Following the interview logic, four informants claimed that overtourism manifestations induced the conflict within the city, which had already turned into the manifested stage. Although the problem areas and conflict parties (stakeholders) have been outlined, it is difficult to determine the scale and the future course of the dispute. In the opinion of the representatives of the city tourism administration and the regional tourism organization, the conflicts were not visible and identifiable. However, their symptoms and the growing interest inconsistencies were already noticed by the professionals and decision makers, and it is them who should be addressed.

In the opinion of up to five informants, the city authorities, the residents’ community and local tourism entrepreneurs were the main parties of the dispute on overtourism. One of them added the international capital representatives (i.e., the real-estate companies, multinational corporations, and property owners from outside Krakow) to this group. The city hall representative claimed that the disputes were local and involved local communities and neighborhoods and local tourist entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, the lack of long-term vision of the tourism development and inactive city authorities were pointed out as the main antecedents of the conflict.

On the one hand, when asked to assess the conflict using the specific criteria (see Table 4), the stakeholders rated the complex core of the dispute (mean assessment 4.17 on a 5-point scale, where 1 represented the lowest and 5 represented the highest level). In addition, the inequality between the parties and the emotional level of the dispute were considered relatively high (respectively, 3.33 and 3.17). On the other hand, the length and the number of parties were considered as the least intense characteristics of the conflict (respectively, 2.50 and 2.00). Moreover, the differentiation in the stakeholders’ ratings was noted only in terms of the emotional level and of the length of the conflict. In detail, the representatives of the city council, the city tourism administration, and the regional tourism organization perceived them as less intensive than other participants.

Table 4.

The intensity of the conflicts in Krakow and Poznan.

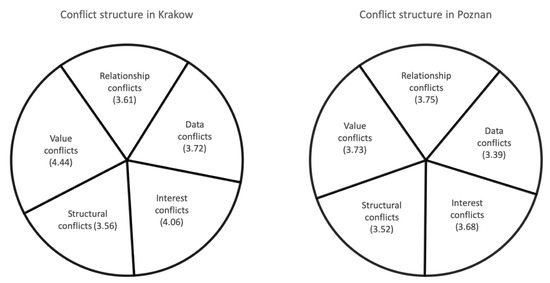

There were no significant differences in how the informants identified the functional causes of the conflict-related issues to overtourism (see Figure 2 and Table 5). The informants mainly stressed the differences in values (mean value 4.44 on a 5-point scale, where 1 represented the lowest and 5 represented the most significant impact). In particular, almost all the informants attached the greatest significance to different aims and expectations of the stakeholders. The interest conflicts, notably inconsistent and competing interests of the parties to the conflict and their material causes, turned out to be another category of the conflict source for most of the informants (4.06). The data conflict was assessed as the third influential category of the causes of the conflict (3.72). Most informants paid attention to a high number of different interpretations of information by the parties to the conflict and incorrect information on its subject. Less intensity was assigned to the relationship and structural aspects of conflicts. The discrepancy between the stakeholders’ opinions was observed in terms of the perceived intensity of the universal conflict constructs. Except for value dimension, all the constructs were valued lower by the public stakeholders, i.e., the city tourism administration and the city council. Significantly, these institutions were considered by other stakeholders as the main parties to the conflict. At the same time, the community and tourist business representatives and also the regional DMO perceived the higher intensity of almost each conflict constructs.

Figure 2.

The circles of conflicts in Krakow and Poznan.

Table 5.

The informants’ assessment of functional causes (universal constructs) of the conflicts in Krakow and Poznan.

Summing up, the overtourism in Krakow was perceived as the significant issue which triggered the conflict that was fueled primarily by different values and concepts of the tourism’s role in urban policy and planning tourism, as well as competing interests of the engaged parties.

4.2. The Conflict Situation in Poznan

Poznan represents the fifth major urban area in Poland, inhabited by approximately 0.54 million citizens [30]. The tourism function in the city has principally developed on the basis of the business and event tourism product [128,129] thanks to the Poznan International Fair infrastructure, one of the most spacious exhibition and conference venues in Central and Eastern Europe [130]. Poznan has hosted to international trade fairs since 1925 [131], while large-scale events such as UN Convention on Climate Change COP 2008 [132] or the 2012 UEFA European Football Championship have played a role in creating the city’s international, business-friendly, and visitor-open image [133]. The incorporation of the tourism sector in the local economy, which paved the way to its contemporary growth, dates back to 1995 when the strategy of Poznan growth was developed with the aim to build a balanced economy, open to investors, economic partners, and tourists [130]. In addition, Poznan aimed to boost the leisure and cultural tourism segments, bundling and promoting offerings related to local historic attractions, for example, the Royal-Imperial Track [134] or the fortifications [135]. According to the latest data available, in 2018, total number of overnights in Poznan amounted to 1.4 million, out of which 27% was realized by foreign tourists, who were mainly from Europe [30]. The five most frequently visited tourist attractions are located in the city center or its neighboring areas [136].

During the research, twelve representatives of the following seven key stakeholders were examined: city tourism organization, the city council, tourism entrepreneurs representing the local chamber of tourism or the independent ones, the residents’ social movement, the public city administration, a key cultural institution, and the old town district council.

According to the vast majority of the informants, tourism had positively impacted the development of the city. Moreover, they claimed that there was still an untapped tourist potential hidden in the city. Thus, in their general opinion, the intensity or even threat of overtourism was scarce and fractional.

Nevertheless, the stakeholders listed many challenges identified as significant in terms of the overall development of the city. The informants identified problems grouped in such categories as night-time entertainment (eight indications), uncontrolled growth of the short-time rental accommodation sector (five indications), pollution of the public space (four indications), transport infrastructure issues (four indications), and loss of local authenticity of urban leisure offerings (two indications) as the most significant. Consequently, the majority of the crucial tourism stakeholders claimed that the disputes triggered by these issues were in the latent stage of evolution and were not identifiable by public opinion. Therefore, they could not yet be precisely addressed. According to the informants, there were no conflicts directly caused by an excessive growth of tourism. Only three out of twelve informants claimed that the conflicts had entered the manifested stage. However, similar to the Krakow interviews, the informants stressed that their assessments were based on subjective opinions, and not the facts and figures.

It should be noted that the informants claimed that the identified nuisances were not strictly associated with the growth of tourism. They perceived tourists just as one of the actors involved in these issues. The city authorities, the residents’ community, and the local entrepreneurs were most often identified as the main parties of the disputes. Additionally, the city and district councilors, and the local tourism organization pointed to the real-estate developers, the party-goers, and the managers and owners of night-time premises. Nevertheless, the informants perceived the challenges interdependently as associated with an uncontrolled consumption of the city’s offerings in general, and not with the overtourism syndrome, as it was demonstrated collaboratively by city dwellers, visitors from metro area, and tourists. Thus, the following results refer to the conflicts related to this complex issue: The informants pointed out the length of the conflict (average assessment 4.1), the complexity of the conflict core (3.66), and the number of parties involved as the most powerful features of the conflict (see Figure 2). They also assessed that the negotiations procedures used in the dispute were not advanced (2.03), and the inequality of the parties was not perceived as significant.

None of the functional causes were assessed as significantly impacted by the nature and dynamics of the conflict (see Figure 2). The relationship and value dimensions were assigned with the highest (and almost equally) impacts (3.75 and 3.73, respectively). However, the differences between the other conflict source constructs, i.e., the interest (3.68) and structural (3.52) were slight. In addition, the informants did not seem to stress the issues of information referring to the conflict core. The intensity of the data sources was assessed as the least important conflict source (3.39); however, still very close to the previously mentioned constructs.

The differences in the informants’ assessments were identified (see Table 5). In general, both the representatives of the formal governmental bodies (i.e., the city council, the city administration) and the representatives of the collective tourism bodies (i.e., the local tourism organization and the chamber of tourism) recognized the lower intensity of conflict source dimensions than the representatives of local community (i.e., the district council and the residents’ association). The average assessments of the former ones ranged between 3.00 and 3.47 as compared with the latter ones, whose evaluations ranged between 3.87 and 4.40. Going into a more in-depth analysis, the significant differences in the opinions grouped as the data dimension were noticed. In detail, they ranged from 2.5 with reference to the city tourism administration and the residents’ social movement, to 4.67 with reference to the old town district council. However, such a discrepancy in the assessment of information is in line with the complex nature of the urban tourism issues. Moreover, the representatives of the city authorities (i.e., the city council and the city tourist administration) and also the tourism entrepreneurs assessed the intensity of the relationship and the interest dimensions lower than the informants representing the residents’ social group, the district city councilor, and the culture institution, who perceived them as the sources which impact the conflict dynamics to the largest extent. Nevertheless, two dimensions of the conflict construct, i.e., the structural sources and the value sources, were assigned with similar rates.

Summing up, even though the informants claimed a lack of the overtourism-related issues in the city’s everyday life, the conflicts related to an uncontrolled consumption of the city offerings were raised. However, the general level of intensity of the conflict sources’ hidden behind it, referenced by the summary of average values in Table 5, is not much lower than in the Kraków conflicts related to overtourism, i.e., 3.61 in Poznan as compared with 3.88 in Kraków. Consequently, no leading commonly recognized source of the conflict was identified.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

As many researchers have highlighted, [1,2,78,137] overtourism is a very complex and multilayer issue. Thus, it also appears to be a hard, measurable, and examinable phenomenon. Moreover, the way it evolves reminds us of the paradoxical position of a boiled frog, which is not aware of being boiled until it is too late. That is why the cases of the destinations affected by the overtourism syndrome [18,70,79,138] tell stories of violent reactions and disruptive changes, although the experts are convinced that its enablers and symptoms could be visible much earlier. However, the dynamics of a conflict situation is determined by the content of the conflict [139]. Thus, the explanatory power of this approach allows for a better understanding of the complicated nature of overtourism through the lens of the social conflict sources incrusted in the disturbances triggered by this syndrome. In this paper, we tried to “map” them using Moore’s CC model. As many conflict theory researchers have indicated, understanding the causes is understanding the social potential to resolve the conflict [37,38,45].

The case studies conducted in two Polish cities which were similar in population and economic potential but different in terms of the tourism development and a recent overtourism experience, let us reveal the social layer of the conflict process and shed more light on the universal (or primary generating) causes of the social disputes accompanying it. In Krakow, the destructive nature of the powers represented by overtourism were revealed. The value dimension had the biggest and the most intense impact on the nature and dynamics of the conflicts related to overtourism. According to Moore [25], the value-related conflicts are difficult to resolve as their nature limits the space for negotiation and compromise. This could explain the rapid course of anti-tourists protests and the conflicts accompanying overtourism. However, the nature of other types of the conflicts referring to interest, data, or relationship dimensions whose intensity was assessed to be also high, are much easier to resolve as there is more space for negotiation, collaboration, and compromise. Therefore, while bearing with the complexity of the whole overtourism process, the key stakeholders should focus primarily on mitigating emerging interest, data, and relationship conflicts induced by the tourism development.

According to the second case study results, although overtourism has not appeared in Poznan as a public issue and the informants manifested the overtourism-free spirit, the city is exposed to this syndrome. First, overtourism is a place-specific phenomenon [1,2], i.e., it does not transmit itself in the same form to other cities. However, it could mean that it is deeply rooted and fares well in the specific local conditions. As overtourism is a negative manifestation of the tourism development, the already existing conflicts and deficiencies could be the cause of this unsustainability. According to the informants’ opinions, the value and structure dimension of the conflicts in Poznan had the most acute and similarly intense impact. As Moore [25] noted, the former is more difficult to resolve than the latter. Since the stakeholders perceived the most subjective dimension as one of the least interacting, it means that they could underestimate the objective, i.e., the rational nature of conflicts related to the development of tourism in the city. Instead, they considered the nature of these problems as subjective. It could be a warning signal of not perceiving the essence of the threat. Second, the identified discrepancies in the informants’ assessment of the functional conflict sources’ intensity indicated that the representatives of the public bodies responsible for tourism governance (the city council, the city tourism administration) and tourism entrepreneurs underestimated the problems. In comparison, the informants representing the “local side” of the conflicts, i.e., the district councilor, the residents’ social movement, and the culture institution, were more aware of the intensity of the conflict in each dimension, which could be a warning signal. Third, the core of the disputes indicated by the informants, i.e., the night-time entertainment, the uncontrolled growth of the short-time rental accommodation sector, and the pollution of public spaces, could also apply to the tourism realm in the city. On the basis of the literature on overtourism [1,2,3], one can argue that almost all the mentioned issues could be the drivers or constituents of the phenomenon.

This article contributes to the knowledge of tourism development within urban destinations by adopting the method adapted from the conflict theory to study the intensity and structure of social conflicts induced by overtourism. In particular, this article verifies the utility of Moore’s [25] Circle of Conflict model in the overtourism context to elaborate on the examination of the structure of conflicts imposed by overtourism. Recent studies dealing with potential social conflicts in the context of overtourism [9,20,21,107] have focused on finding a substantial core of conflicts. Adopting the CC model to two cities let the researcher not only study the substantial causes of the conflicts, but also understand their functional structure, rooted in the relationship, data, interest, structural, and value causes. Thus, the article complements the method of studying overtourism in urban destinations with the method of deconstructing the conflicts which are the part of the phenomenon. Moreover, the observed symptoms allow to assume that the overtourism and the challenges posed by it will evolve and will impact a growing number of destinations. In this vein, it appears sound to further continue developing and validating the tools to diagnose and manage the conflicts. Future research could benefit by incorporating the view Horowitz [46] applied and reflected on the ethnic conflict. This approach focuses on recognizing the lack of understanding between two or more parties with regard to symbols and values. As Burton [45] noted, the desirable solution to the conflict consists of taking into account the broad context of the given situation and building an environment which creates valuable relations between the parties to the conflict. This perspective should be an inspiration for seeking solutions in theoretical and practical discussion on (over) tourism conflict. Furthermore, the article contributes to the conflict studies by applying Moore’s [25] Circle of Conflict model to identify and understand the social conflicts caused or related to such a very complex, multilayered, and dynamic phenomenon as overtourism.

In our opinion, some of the previous studies on conflicts are in line with the current debate on handling overtourism. Among others, a key approach is the tourism sustainable development, notably the inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders (residents’ empowerment, governance). As Morton Deutsch explains, the father figure in the field of the conflicts research, the relations between the parties involved influence both the antagonism creation and the dispute course. Yet, as the author adds, the dynamics of the conflict situation is determined by the content of the conflict [139]. Therefore, the study presented in this article contributes to the body of literature on overtourism, indicating a potential level of the phenomenon by deconstructing the functional structure of the conflicts related to it. As both study cases showed, the value dimension had the biggest and the most intense impact on the nature and dynamics of conflicts. It is usually associated with the social valuation of space (local and national identity space) in which the competition between residents and guests takes place.

As Burton [45] notes, in each conflict, human traits play a significant role (constituting the ontological basis and universal essence of the conflict); generalizing, it points to three basic sources of the conflict situations, i.e., needs, values, and interests. The results of our research correspond with this statement. The deprivation of residents’ needs of (often gradually increasing over time) is widely commented on in the overtourism literature (see, among others, issues of gentrification intensified by the tourism development [16,115]). The problem is also related to the problem of social control, whose lack (or its unreliability) is perceived in the overtourism destinations as a threat or a way to social anomy. They are the genesis of variously expressed anti-tourist protests [7,8,9,16]. Some of the protests, as some of the authors in the overtourism field, allude in the narration to the dichotomous division introduced by Marx and continued by Dahrendorf. The social world splits between the dominant and subordinate groups, where each of them presents counter interests. Yet, as Adamus-Matuszyńska [38] observed, the contemporary interests of groups stemmed from complex economic, social, and politic phenomena. These factors hinder the conflicts interpretation in terms of the social class dichotomous division. Following Axel Honneth [47], the core of the present social conflict (including overtourism) is rather the recognition of the realm and not of the social equality. The conflicts caused by overtourism (as long as they are not in the conflict with fundamental values and interests) also stimulate the emergence of new rules and institutions (e.g., the Night Mayor) as well as the norms ordering social relations in the group, which is in line with Coser’s assumption [44].

The escalating conflicts of overtourism are emanation of an unsustainable situation that signals the disfunctions and stimulates the key institutions to search for and undertake necessary actions [15]. Moreover, the emerging protests, which are an integral constituent of the overtourism social phenomenon [7,8,9] could have a diagnostic role in overtourism and overtourism management, because they expose some weaknesses and problems of the local tourism system and urban policy, as well as reveal the differences and the existence of interest groups. As Kreiner et al. [24] note, “(i)n many tourism-focused communities, tourism development significantly influences social conflict. By bringing in more groups and subgroups, tourism development alters and complicates the scope and nature of conflicts, thereby influencing the social structure and bringing about cultural change within local communities. The disputes that emerge typically revolve around the conflicting interests, values, and goals espoused by different stakeholders”. Moreover, following Burton [45], it is worth noting that the current deeper social problems are also reflected in the conflicts. In this sense, the overtourism conflict (usually associated with urban transformation) is their signal. As an attribute of social change [39], (over)tourism conflict can simultaneously be the cause of other social processes [38]. Despite the assumption adopted in the literature about the normality of conflicts in the social system, their ubiquity and, to some extent, utility (…), there is an agreement on the need to overcome them.

Finally, the limitations of the study should be identified. First, the literature almost entirely exclusively focused on international (i.e., English language) journals indexed in Scopus and Web of Science, with the exclusion of the tourism-related work published elsewhere (books, book chapters, and conference papers). In addition, due to delineation of the scope of the core analysis, only those papers in which the term “overtourism” was used were included. Secondly, the limitations related to the case study method as having limited potential for generalization and limited readability [35] should be mentioned. The contextual character of the research, possible response bias, and the limited number of informants limits the conclusions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.-A. and P.Z.; methodology, P.Z. and J.K.-A.; validation, P.Z. and J.K.-A.; Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, J.K.-A.; Section 3.3, M.D.; Section 3.4, P.Z.; destination context J.K.-A., P.Z., and M.D.; results, P.Z. and J.K.-A.; discussion and conclusions, P.Z. and J.K.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Z., J.K.-A., and M.D.; writing, P.Z.; supervision, P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by both universities’ funding schemes: PUEB’s internal grant program called “PUEB for Science—Novel directions in the field of economics” (project title: “Evolution of inter-organizational relationships as the result of sharing economy’s development: micro, meso and macroeconomic implications”); the PUEB’s statutory research project “Conditions for competitiveness of tourism businesses and destinations”; and the UL’s statutory research project “Urban tourism hypertrophy”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

List of Papers Included in the Core Systematic Literature Review

- i.

- Cheung, K.S.; Li, L. Understanding visitor—resident relations in overtourism: developing resilience for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1197–1216.

- ii.

- Milano, C. Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. Pasos. Rev. Tur. y Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 551–564.

- iii.

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1857–1875.

- iv.

- Sánchez Cota, A.; Salguero Montaño, Ó.; García García, E.; Rodríguez Medela, J. Urban social struggles in Andalusia: Approaches to the politicization of our daily lives. In Andalusia: History, Society and Diversity; Bermúdez-Figueroa, Roca, B., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Jerez, Spain, 2018; pp. 157–195. ISBN 9781536144406.

- v.

- Namberger, P.; Jackisch, S.; Schmude, J.; Karl, M. Overcrowding, Overtourism and Local Level Disturbance: How Much Can Munich Handle? Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 452–472.

- vi.

- Novy, J.; Colomb, C. Urban Tourism as a Source of Contention and Social Mobilisations: A Critical Review. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 358–375.

- vii.

- Novy, J. Urban tourism as a bone of contention: four explanatory hypotheses and a caveat. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 63–74.

- viii.

- Oklevik, O.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Jacobsen, S.; Grøtte, I.; McCabe, S. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1804–1824.

- ix.

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futur. 2017, 3, 144–156.

- x.

- Smith, M.K.; Sziva, I.P.; Olt, G. Overtourism and Resident Resistance in Budapest. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 376–392.

- xi.

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban tourism hypertrophy: Who should deal with it? The case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 247–269.

Appendix B

Table A1.

The interview design template.

Table A1.

The interview design template.

| Main Topic | Questions Asked/Ancillary Options for Researcher |

|---|---|

| A. Extent of overtourism in the city | What problems and challenges resulting from the development of tourism do you observe in the city? |

| What is the importance of mentioned issues in terms of further development of tourism and the entire city? | |

| B. The nature and dynamics of the conflict referring to tourism | At what stage is the conflict caused by the excessive development of tourism in the city? |

| What are the main antecedents/causes of conflict? | |

| What are the key parts of this conflict? | |

| Rate the intensity of the conflict according to the following criteria: the complexity of the subject of the conflict; levels of emotions; imbalance among the parties; the parties’ ability to solve the conflict; duration of the conflict; number of the participating parties; advancement of procedures. | |

| To what extent do the following factors influence the nature and dynamics of the conflict? | |

| – Fueled emotions and incompatible attitudes | |

| – Prejudice, discrimination, stereotyping, lack of trust | |

| – Lack or poor communication between parties | |

| – Inaccurate information concerning overtourism | |

| – Unequal access to different data by parties | |

| – Different ways of assessing and interpretation of data, contradictory research results | |

| – Conflicting or competing interests | |

| – Personal aspirations and particular interests of individuals | |

| – Material interests (money, property, resources, infrastructure) | |

| – Power inequality, the privileged position of one party resulting from legislation, procedures, policies, hierarchical structure, or decision-making power in the problem domain | |

| – Inequality of control and property | |

| – Perceived or actual competition over limited resources | |

| – Organizational, spatial, and time constrains perceived by parties | |

| – Differences in objectives and expectations among the parties | |

| – Differences in ideologies, moral concepts, and lifestyles | |

| – Different concepts of urban policy and planning, land use, and tourism role in urban development | |

| C. Organizational affiliation | Name of organization Its role in the tourism governance system |

References

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The phenomena of overtourism: A review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. The Challenge of Overtourism. Available online: https://haroldgoodwin.info/pubs/RTP’WP4Overtourism01′2017.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J. Overtourism and degrowth: a social movements perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1857–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism carrying capacity research: a perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. “Overtourism”: Old Wine in New Bottles? Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/overtourism-old-wine-new-bottles-dianne-dredge/ (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futur. 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. Introduction. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-3-11-062045-0. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, J.; Colomb, C. Urban Tourism as a Source of Contention and Social Mobilisations: A Critical Review. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U. The role of social media in creating and addressing overtourism. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Phi, G. Framing overtourism: a critical news media analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; De Lleida, O.-U. Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. PASOS. Rev. de Turismo y Patrim. Cult. 2018, 18, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, M. Overtourism and Resistance; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2019; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, E.E. The Management of Protracted Conflict: Theory and Cases; Dartmouth Publishing Company: Aldershot, UK, 1990; ISBN 10:1855210630. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Włodarczyk, B. Przestrzeń turystyczna przestrzenią konfliktu/Tourism space as space of conflict. Pr. i Stud. Geogr. 2017, 62, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban tourism hypertrophy: Who should deal with it? The case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee-Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2018)629184 (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- McKinsey; WTTC. Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding in Tourism Destinations. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/policy-research/coping-with-success---managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations-2017.pdf?la=en%0Ahttps://sp.wttc.org/about/%0Ahttps://sp.wttc.org/about/ (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- UNWTO. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Padilla, Y.; Cerezo-Medina, A.; Navarro-Jurado, E.; Romero-Martínez, J.M.; Guevara-Plaza, A. Conflicts in the tourist city from the perspective of local social movements. Boletín la Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 83, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Sziva, I.P.; Olt, G. Overtourism and Resident Resistance in Budapest. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]