Abstract

Implementing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and increasing environmental issues provokes changes in consumers’ and stakeholders’ behavior. Thus, stakeholders try to invest in green companies and projects; consumers prefer to buy eco-friendly products instead of traditional ones; and consumers and investors refuse to deal with unfair green companies. In this case, the companies should quickly adapt their strategy corresponding to the new trend of transformation from overconsumption to green consumption. This process leads to increasing the frequency of using greenwashing as an unfair marketing instrument to promote the company’s green achievements. Such companies’ behavior leads to a decrease in trust in the company’s green brand from the green investors. Thus, the aim of the study is to check the impact of greenwashing on companies’ green brand. For that purpose, the partial least-squares structural equation modeling (PLS-PM), content analysis and Fishbourne methods were used. The dataset for analysis was obtained from the companies’ websites and financial and non-financial reports. The objects of analysis were Ukrainian large industrial companies, which work not only in the local market but also in the international one. The findings proved that a one point increase in greenwashing leads to a 0.56 point decline in the company’s green brand with a load factor of 0.78. The most significant variable (loading factor 0.34) influencing greenwashing was the information at official websites masking the company’s real economic goals. Thus, a recommendation for companies is to eliminate greenwashing through the publishing of detailed official reports of the companies’ green policy and achievements.

1. Introduction

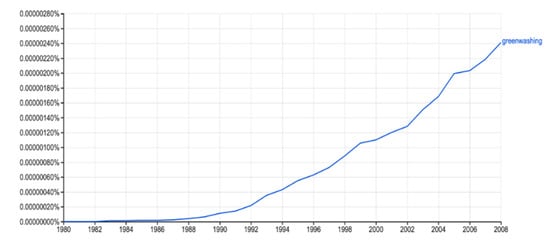

The snowballing effect of extending the green lifestyle, as well as the promoting of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the purpose of overcoming environmental issues, contribute to the developing of companies’ mission, strategy and policy considering the green trends. At the same time, the open boundaries of the world market provoke a considerable level of competitiveness, which contributes to the producing of a high-quality product. The transformation of focus from overconsumption to a green or eco-friendly lifestyle provokes the changing of consumer behavior. Consequently, it leads to an increasing demand for green products or services provided by green companies. It pushes companies to modernize their technologies, making products eco-friendly accordingly to SDGs principals. From one point of view, such innovation of green technologies contributes additional financial resources. In this case, the green investment is one of the alternative options to finance such modernization. Noted, from the other side, the competition for the green investors and consumers provokes the use of greenwashing by companies as unfair marketing instruments. Greenwashing was first described by Jay Westerveld in 1986 with examples from the hotel industry [1]. Thus, the hotel tries to advertise their awareness of environmental issues by using towels more than one time. In practice, the hotel management tried to save money on clean towels. At the same time, the results of the analysis of scientific sources using the instrument Google Ngram Viewer showed that the frequency of using greenwashing on the publication started to increase at the beginning of 2000 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamics of the frequency of greenwashing use (defined by the Google Ngram Viewer tool).

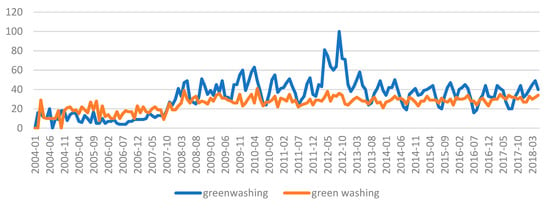

Additionally, using the Google Trends Instrument, the frequency of greenwashing use from 2004 to 2018 was identified (Figure 2). As greenwashing could be written in the Internet in two ways—“green washing” and “greenwashing”, the two options were checked. Considering the findings, in 2012, the frequency of searching “greenwashing” was higher than the other years.The findings proved that worldwide scientists’ interest in greenwashing increased in the period of the extending of SDGs, as well as when banks started to allocate finance for green projects. The abovementioned trends actualized the theme of the investigation.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of the frequency of “greenwashing” use (defined by Google Trends).

Westerveld, Siano, Vollero and Conte [1,2] define greenwashing as a discrepancy between two types of behavior: low eco-efficiency and the promotion of green or short-term sustainable development goals. Note, that greenwashing used to promote green benefits instead of real investment in green projects that reduce negative environmental impact. For the most part, greenwashing is used by industrial companies (oil, chemical, automotive, etc.) to develop a green brand and promote their products as eco-friendly. Thus, according to expert estimates, on “the first Earth day” in 22 April 1970, companies spent more than $1 billion on greenwashing, which was far more than what they spent on green technology [2]. The Chinese scientists Du, Chang, Zeng, Du and Pei, in the papers [3,4] investigated the features of listing on the Chinese stock market and concluded that use of greenwashing by companies adversely affects the value of the company’s securities that were listed on the stock exchange. The scientists Kim and Lyon had argued that using greenwashing leads to increased skepticism among green investors in a green marketing campaign [5].

According to reports [6,7], use of greenwashing by Volkswagen in 2015 led not only to losses of €7 billion in profits but also to a decrease in investments and reputational losses (the value of the company’s shares decreased by 25%). The chain reaction to this scandal provoked a decline in consumer confidence in the brand “Made in Germany”, as well as the investment attractiveness of the car market. In 2015, the value of the shares of all automobile companies decreased by 3–14% (Toyota—by 3.24%, BMW—88%, Honda—13.73%, Ford—12.42%, General Motors—4.32%, Mercedes—6.51%, Fiat—5.97%) [6,7]. Thus, using greenwashing negatively influences the company’s green brand, which provokes the outflow of green investment from the company. In this case, the aim of the paper is an analysis of the impact of greenwashing use on companies’ green brand. The main hypothesis of the investigation was checking the impact of greenwashing on the green brand of the company.

2. Materials and Methods

The results of the analysis showed that the scientist had not accepted a universal approach to identifying the impact of greenwashing on the green brand. The Chinese scientist Chan [8] explored the impact of greenwashing on the hotel business using t-tests and an ANOVA model. The information base of the study was generated based on the top hotel management survey data. The questionnaire contained thirty parameters that influence the hotel’s brand. The scientists proved that the Internet is the most effective channel for promoting green hotel initiatives in the B2C market (business-to-consumer market). Besides, the study assessed the impact of skill level, gender and demographic factors on the perception of greenwashing and the relevant marketing strategy. Nevertheless, survey data could not allow making an objective conclusion as the raw database was made up of subjective estimations.

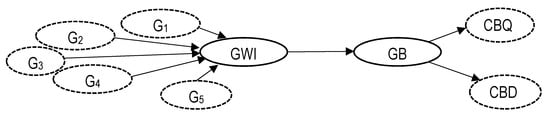

Wahba [9] examined the impact of green advertising on consumer behavior and evaluated greenwashing as a cultural aspect of environmental advertising. In doing so, it distinguishes the following components of environmental advertising: environmental culture, design, environmental consumers and environmental messaging. Wahba emphasized that all of these components were interconnected and had a co-integration relationship. He demonstrated that 68% of consumers perceive any environmental advertising a priori as being untrue, that is, using greenwashing. In turn, it causes a chain effect in the form of increased levels of distrust in the advertising services market. Langen, Grebit and Hartmann [10] used the logit model and the logistic regression model to check the impact of greenwashing use by companies on consumer behavior. For the evaluation, the scientists used the 7-dimensional scale of summary estimates of Likert. Considering the abovementioned results and the fact that greenwashing has abstract and complex indicators which are formed by different parameters, the methods of partial least-squares structural equation modeling (PLS-PM) was used. PLS-PM is a tool for modeling the relationships between latent (implicit) variables. The PLS-PM technique was used to analyze high dimensional data in a poorly structured environment. For the analysis, both types of reflective and formative models of PLS-PM were used. Thus, for estimating greenwashing the formative type was used, and for the green brand—the reflective model. The graphic illustration of the research hypothesis is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relationship between greenwashing and the green brand of the company.

Greenwashing (GWI) has an impact on the company’s green brand (GB). is used in the model of the reflective type. Thus, the latent variable is the cause of the variable: comparative and target indexes. Under the research, the variables (comparative and target indexes of the green brand) reflect the latent variable Using the PLS-PM, the latent variable of greenwashing and green brand was estimated by Formula (1):

where = free variable; = loading factor and connection ratio; = explicit variables ; , = explicit variables (target and comparative indexes) of the green brand index; = standard error; j = block of the corresponding variables for the t-period; and k is the number of variables.

Note, that if > 0.7, variables had a statistically significant impact and if < 0.7, variables did not have a statistically significant impact on the indicator.

Despite the numerous studies on the evaluation of greenwashing, the worldwide scientific community has not accepted a unified and general approach. In 2007, EnviroMedia Social Marketing developed EnviroMedia’s Greenwashing Index. The company had set up a website that allowed stakeholders to inform about the environmental compliance of their declared green goals on a scale of 1 to 5. However, that approach considered the subjective perception of consumers by the information submitted about the green activities of the company. In this case, under the research, it was proposed to estimate greenwashing (GWI) by the use of content analysis.

It should be noted that Max Weber used content analysis as a sociological method. The scientists Camprubi, Coromina, Nur-Al-Ahad and Nusrat determined that content analysis is a traditional method of research in the social sciences [11,12,13]. Content analysis is commonly used to study various forms of human communication, including the analysis of written documents, photographs, films or videos, as well as audiotapes [11,12]. Studying the use of content analysis in tourism, Camprubi and Coromina [11], based on the research of scientists Kolbe and Burnett [14], defined content analysis as an observation method used to systematically evaluate the symbolic content of all recorded forms of communications. According to Berg and Paisley [15,16], content analysis is a detailed, systematic study and interpretation of material to identify patterns, themes, prejudices, and meanings; and it could be analyzed as a phase of information processing in which the content of communications was transformed, through the objective and systematic application of categorization rules, into data that can be generalized and compared. Guthrie, Petty, Soldatenko and Backer [17,18] proved that content analysis was a method for the collecting and organizing of massive data, including encoding information into different groups or categories based on selected criteria. Jones, Schoemaker and Testa suggested that content analysis allowed to identify specific trends, attitudes, or categories of content from the text, and then draw conclusions from it [19,20]. Based on the above, content analysis was used as a method to estimate GWI, which allows minimizing the subjective evaluation. For that purpose, five questions were formulated:

- The information about the company’s green activities on the official website was not right (G1);

- A report on corporate social responsibilities was not presented at the company’s website (G2);

- The information on the official website could not be proven by real data (G3);

- The information about the green achievement on the company’s website was exaggerated (G4);

- The information on the official website masked the company’s real economic goals (G5).

The variance inflation factor (Formula (2)) allows checking the multicollinearity of the results of the content analysis:

where is the coefficient of determination of i-th regressor Xi for all other regressors; i = 1, ..., k; and k is the number of factors of the model.

Variance inflation factor (VIF) allows to estimate how many times the variance of the regression coefficient increases due to the correlation of the regressors X1, ..., Xi compared to the variance of this coefficient, if the regressors were not correlated. If VIF > 3.33—multicollinearity—data are not suitable for further calculations, and if VIF < 3.33—no multicollinearity—data are suitable for further calculations.

At the second step, the green brand of the company was estimated by using a combination of the methods. Traditionally, the company’s brand was estimated as market capitalization or as a consumer attitude towards the brand. At the same time, the abovementioned results of the analysis showed that the brand was a complex indicator that involved qualitative and quantitative parameters. Thus, the scientists suggested that energy-efficient projects [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], the efficiency of green marketing [31,32] and intellectual capital [33,34,35] increased the company’s image and capitalization [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. The scientists in the papers [46,47,48,49,50] demonstrated that corporate social responsibility influences the brand. The group of the scientists proved that an imbalance in financial sectors [51,52,53,54,55,56], green development [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], shadow economy and corruption [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75], innovation technologies [67,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] and a country’s attractiveness [67,82,83,84,85] influence the investment climate in the country and the company’s image [86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. Considering the abovementioned results of analysis, we proposed to estimate the green brand as the combination of two indexes: comparative (which involves the economic parameters of the company’s activities) and target (which involves three composite indicators: environmental operation; company’s activity; investment for ecological modernization; and relevance to the indicative green goals of the company). Variables and explanations is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Target variables for the company’s green brand estimation.

With the purpose of estimating each indicator, the authors used content analysis. Using content analysis, researchers can quantify and analyze qualitative parameters and evaluate and correlate qualitative and quantitative parameters. Each indicator was rated from 0 to 2: 0 = no information; 1 = available information, but no detail; 2 = comprehensive information available for defined indicators. The target index is calculated by Formula (4):

where = weight coefficients, which were determined by the Fishbourne method:

where N = the number of sample metrics, and i = the index number of the sample.

The approaches developed by Fetcher [86] and modified by Lyulyov [87,88] were used for the estimation of the comparative index. According to the Fetcher and Lyulyov approaches, the target index could be calculated as Equation (6):

where i = company; S = sales volume of goods; GI = green investment; HR = labor turnover; ET = environmental taxes; EP = volumes of environmental fines and payments; and ST = the market value of the company’s shares.

Each parameter of the comparative component of the green brand was estimated as deviations from the average value of each indicator (Formula (7)):

where i = company; S = sales volume of goods; GI = green investment; HR = labor turnover; ET = environmental taxes; EP = volumes of environmental fines and payments; and ST = the market value of the company’s shares.

All indicators from Formula (7)—sales volume of goods, green investment, labor turnover, environmental taxes, volumes of environmental fines and payments and the market value of the company’s shares were obtained from the financial statements of the companies, which were located in the companies’ websites, and from specialized platforms such as the “Ukrainian Stock Market Infrastructure Development Agency”.

All parameters were classified as stimulators and de-stimulators and normalized:

The financial and non-financial companies’ reports and information found on the companies’ websites were used for the analysis. The objects of analysis were the Ukrainian big industrial companies PrJSC “Dneprospetsstal”, PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih” and the Metinvest Group were chosen for the three years of 2014–2017 (after the military conflict had already begun). These companies are the leading industrial companies in Ukraine based on the companies’ value and revenue, which operate not only at the local market. Besides, these companies declared that they implemented a green strategy considering sustainable development goals.

3. Results

Using Equation (2) of Formula (1) and the results of the content analysis for the three companies PrJSC “Dneprospetsstal”, PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih” and the Metinvest Group, the functioning of greenwashing could be presented as:

Note, that checking for multicollinearity showed that all data could be used for further calculation. The results of checking for multicollinearity are shown in Table 2. All findings were statistically significant as > 0.7.

Table 2.

Findings of the variance inflation factor and calculations.

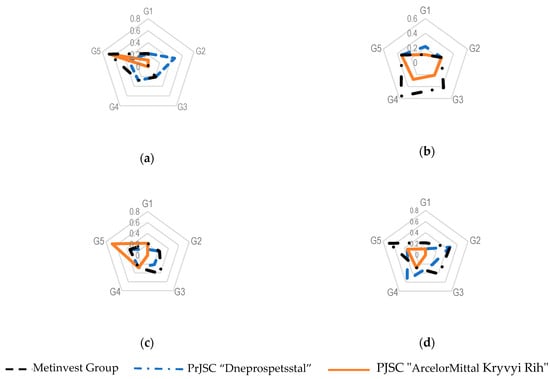

The results of the assessment of greenwashing are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Results of the assessment of the greenwashing variables in (a) 2014; (b) 2015; (c) 2016; and (d) 2017.

Thus, in 2014 PJSC ArcelorMittal Kryviy Rih and Mentinvest Group had the lowest of variable G5 (the information on the official website masked the company’s real economic goals). At the same time, PJSC Dniprospetsstal had the lowest value of variable G2 (the non-financial report was not presented on the official website). In 2015, the trend in terms of indicators changed. Thus, Metinvest Group had improved its position on almost all variables. In this case, the indicator G4 (the information about the green achievement on the official website was exaggerated) deteriorated. In 2016, the diagram for PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryviy Rih” was the same size as in 2014; Metinvest Group and PJSC “Dniprospetsstal” improved their values for almost all indicators. According to the findings of PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryviy Rih” in 2017, it had the best value in all the variables. At the same time, PJSC Dniprospetsstal and Mentinvest Group significantly worsened their positions. In the first place, this may be triggered by an ineffective strategy of reorienting these companies to the European market. Additionally, political and economic conflicts in Ukraine pose adverse effects. Additionally, as in JSC Dniprospetsstal and Mentinvest Group, the management partially published information about the green goals of the companies. Note that lack of clarity, confusion and lack of transparency in the management structure of the Mentinvest Group lead to an increase in mistrust toward the company, which in turn negatively affected its image and outflow of investments. The generalized results of the greenwashing assessment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Findings of greenwashing assessment.

The empirical results of the analysis proved that PJSC “ArcelorMittal” had the highest level of the green brand (Table 4). It should be noted that its values were much lower than similar companies in the EU and the US.

Table 4.

Findings of green brand assessment (2014–2017).

The findings showed that for the years 2014–2017, PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryviy Rih” had the lowest value of the greenwashing. G5 had the most significant influence on the response of stakeholders to the elements of unfair promotion and positioning of goods and services as eco-friendly.

In connection with these Ukrainian companies, it is necessary to implement the experience of world-leading companies on the increasing of the green brand. Formula (1) could be rewritten considering the abovementioned findings as:

According to the results, the target and comparative indexes of the green brand had the same impact force and load factor (0.76 and 0.78, respectively). An increase by one point of the target and comparative indexes leads to an increase of the green brand by 0.87 and 0.9, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Empirical findings of greenwashing impact on green brand with force and load factor.

The results showed that a one point increase of the greenwashing leads to a 0.56 point decline of the company’s green brand (a load factor of 0.78). That is, the data indicated that the analyzed factors had a significant impact.

Based on the empirical results of assessing the impact of greenwashing on the green brand, the values of the load and link coefficients, the data on the green brand and the companies’ green brand were calculated considering the consequences of using greenwashing. Table 6 contains the results of the assessment.

Table 6.

Finding green brand assessment (2014–2017) with greenwashing.

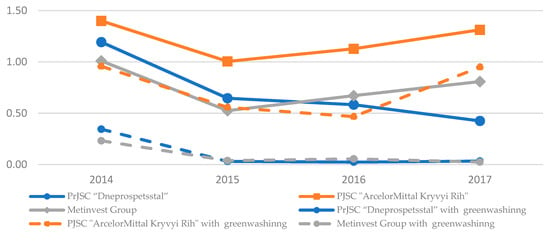

The graphic interpretation of the impact of companies using unfair green marketing policies is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Findings of green brand assessment before and after use of greenwashing.

The level of the green brand of PJSC “ArcelorMittal Kryviy Rih” before the inclusion of the greenwash for 2014–2017 was 1.01–1.34, and after the consideration it was 0.47–0.96. The findings show that greenwashing harms the green brand of the company. Thus, the index of the green brand was higher before considering greenwashing.

4. Discussion

Empirical data have allowed substantiating the directions and mechanisms of increasing the volume of attracting green investments and increasing the level of trust of stakeholders in a green, responsible company. Thus, the primary task for companies is to reduce the use of greenwashing and to increase the trust of stakeholders by publishing the non-financial and financial reliable information of the company on official online platforms. This process should be done while considering the features as follows:

- The information on the website has to be reliable and characterize the green activity of the company;

- Full-text non-financial statements of the company;

- The information available on the website must be supported by specific figures, press releases and relevant activity and environmental audit reports;

- Mandatory information on the company’s official website about the environmental performance of the company.

In this case, it is advisable to publish the data of official experts and audits. It should be noted that a significant factor is publishing on the site of available certificates of product and management quality with the publication of environmental audit reports. Considering the economic interests of the stakeholders who are interested in the company’s capitalization, it is necessary to:

- Present a transparent scheme of the shareholders of the company;

- Publish information about listing in green stock indices and the stock price of the company;

- Publish reports on using green investments with verified data on green assets to which they have been directed at each life cycle of the investment project;

- Publish information about data on the issue of green securities and information on the direction of funds raised as a result of this issue.

5. Conclusions

The abovementioned analysis and findings were obtained by using the methodology proposed by the authors. The developed comprehensive approach integrates content analysis and the PLS-PM method, which allowed substantiating the directions of increasing the volume of attracting green investments and increasing the level of stakeholder confidence in the green policy of the company. The authors proved the general hypothesis on the impact of greenwashing on the company’s green brand. The results of the study show that one of the key factors for attracting green investments by companies in the green brand. This conclusion on greenwashing impact was the same as the finding that were obtained by the scientists in papers [4,5,6]. Additionally, considering the recommendation in papers [3,9,10], a decrease of greenwashing will increase a company’s transparency trough publishing the financial and non-financial reports of company’s green policy and achievements. It will make it impossible for companies to use greenwashing and provoke an increase of green brand and consequently attract additional green investments. In this direction, an indispensable condition is the establishment of an institutional interaction of green investment stakeholders. For further investigations, it is necessary to analyze the mechanisms (at the government level) of declining the use of greenwashing by the companies. Additionally, the link between greenwashing and green brand at the country’s level should be understood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S., T.P. and Y.B.; methodology T.P. and Y.B.; validation, J.H., L.S. and W.G.; formal analysis, J.H., L.S. and W.G.; data curation, L.S. and T.P.; writing and visualization, T.P., Y.B., J.H., L.S. and W.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (Nos. g/r 0117U003932).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Motavalli, J. A History of Greenwashing: How Dirty Towels Impacted the Green Movement. 2011. Available online: https://www.aol.com/2011/02/12/the-history-of-greenwashing-how-dirty-towels-impacted-the-green/ (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Siano, A.; Vollero, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S. “More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X. How the Market Values Greenwashing? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 128, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Chang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Du, Y.; Pei, H. Corporate environmental responsibility (CER) weakness, media coverage, and corporate philanthropy: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 33, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Lyon, T.P. Greenwash vs. Brownwash: Exaggeration and Undue Modesty in Corporate Sustainability Disclosure. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, L. What Is Green Marketing? (+5 Sustainable Examples in 2019). Available online: https://learn.g2crowd.com/green-marketing (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- The Domino Effect of Volkswagen’s Emissions Scandal. 2015. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2015/09/28/the-domino-effect-of-volkswagens-emissions-scandal/#3258544d282b (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Chan, E.S. Managing green marketing: Hong Kong hotel managers’ perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, G.H. Latest Trends in Environmental Advertising Design “Application Study of Egyptian Society”. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 51, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Langen, N.; Grebitus, C.; Hartmann, M. Is Cause-related Marketing greenwashing. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial ISEE Conference Advancing Sustainability in a Time of Crisis, Oldenburg and Bremen, Germany, 22–25 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Camprubí, R.; Coromina, L. Content analysis in tourism research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, M.; Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1984, 79, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-Al-Ahad, M.; Nusrat, S. New Trends in Behavioral Economics: A Content Analysis of Social Communications of Youth. Bus. Ethic Lead. 2019, 3, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, R.H.; Burnett, M.S. Content-Analysis Research: An Examination of Applications with Directives for Improving Research Reliability and Objectivity. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. An Introduction to Content Analysis. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 338–377. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85654/ (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Levin, J.; Gerbner, G.; Holsti, O.R.; Krippendorff, K.; Paisley, W.J.; Stone, P.J. The Analysis of Communication Content: Developments in Scientific Theories and Computer Techniques. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1970, 35, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Petty, R.; Yongvanich, K.; Ricceri, F. Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. J. Intellect. Cap. 2004, 5, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatenko, D.; Backer, E. A content analysis of cross-cultural motivational studies in tourism relating to nationalities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J.; Shoemaker, P.A. Accounting narratives: A review of empirical studies of content and readability. J. Acct. Lit. 1994, 13, 142–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yevdokimov, Y.; Chygryn, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Lyulyov, O. Biogas as an alternative energy resource for Ukrainian companies: EU experience. Innov. Mark. 2018, 14, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chygryn, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Luylyov, O.; Goncharova, A. Green Bonds like the Incentive Instrument for Cleaner Production at the Government and Corporate Levels: Experience from EU to Ukraine. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 9, 1443–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnyk, I.M.; Dehtyarova, I.B.; Kovalenko, Y.V. Current threats to energy and resource efficient development of Ukrainian economy. Actual Probl. Econ. 2015, 173, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Štreimikiene, D.; Vilnius University; Mikalauskiene, A. Comparative Assessment of Sustainable Energy Development in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia. J. Compet. 2016, 8, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sotnyk, I.; Kulyk, L. Decoupling analysis of economic growth and environmental impact in the regions of Ukraine. Econ. Ann. XXI 2014, 7–8, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tvaronaviciene, M.; Prakapienė, D.; Garškaitė-Milvydienė, K.; Prakapas, R.; Nawrot, Ł. Energy Efficiency in the Long-Run in the Selected European Countries. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyo, A.; Jazykbayeva, B.; Ten, T.; Kogay, G.; Spanova, B. Development tendencies of heat and energy resources: Evidence of Kazakhstan. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnyk, I.M.; Volk, O.M.; Chortok, Y.V. Increasing ecological & economic efficienICTof ict introduction as an innovative direction in resource saving. Actual Probl. Econ. 2013, 147, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, D. Decoupling CO2 Emissions in Nordic countries: Panel Data Analysis. Socioecon. Chall. 2019, 3, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyeonov, S.; Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Štreimikiene, D.; Mentel, G. Assessment of Green Investments’ Impact on Sustainable Development: Linking Gross Domestic Product Per Capita, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Renewable Energy. Energies 2019, 12, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, S.A.; Azmoon, I.; Fekete-Farkas, M. The Impact of Perceived Sustainable Marketing Policies on Green Customer Satisfaction. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, M.D.P.S.R.; Vargas-Hernández, J.G. Analysis of the Determinants of Social Capital in Organizations. Bus. Ethic Lead. 2019, 3, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Shen, Y. RISKY MULTI-CRITERIA GROUP DECISION MAKING ON GREEN CAPACITY INVESTMENT PROJECTS BASED ON SUPPLY CHAIN. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E.T.; Mapuranga, M.; Maramura, T.C.; Nzewi, O. Navigating on the key drivers for a transition to a green economy: Evidence from women entrepreneurs in South Africa. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 1686–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mačerinskienė, I.; Survilaitė, S. Company’s intellectual capital impact on market value of Baltic countries listed enterprises. Oeconomia Copernic. 2019, 10, 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadinugroho, B.; Haryono, T.; Payamta; Trinugroho, I. Leverage, firm value and competitive strategy: Evidence from Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Policy Emerg. Econ. 2018, 11, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. The Relationship between Macro-Economic Variables and Stock Exchange Prices: A Case Study in Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) in Bangladesh. Financ. Mark. Inst. Risks 2019, 3, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoemadi, F.R.; Setiawan, M.; Noermijati, N.; Irawanto, D.W. The effect of work satisfaction on employee engagement. [Wpływ satysfakcji z pracy na zaangażowanie pracowników]. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyja, P. The role of the state in creating green economy. Oeconomia Copernic. 2016, 7, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyarko, I.M.; Samusevych, Y.V. Role of intangible assets in company’s value creation. Actual Probl. Econ. 2011, 117, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tresna, P.W.; Chan, A.; Alexandri, M.B. PLACE BRANDING AS BANDUNG CITY’S COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE. Int. J. Econ. Policy Emerg. Econ. 2019, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haninun, N.; Lindrianasari, N.; Denziana, A. The effect of environmental performance and disclosure on financial performance. Int. J. Trade Glob. Mark. 2018, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaas, M.S.M.; Chygryn, O.; Kubatko, O.; Pimonenko, T. Social and economic drivers of national economic development: The case of OPEC countries. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zacarías, M.A.V.; Aguiñaga, E.; Lagunas, E.A. Sustainable entrepreneurship in industrial ecology: The cheese case in Mexico. Int. J. Trade Glob. Mark. 2017, 10, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasylieva, T.; Lyulyov, O.; Bilan, Y.; Štreimikiene, D. Sustainable Economic Development and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: The Dynamic Impact of Renewable Energy Consumption, GDP, and Corruption. Energies 2019, 12, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, T.A.; Lasukova, A.S. EMPIRICAL STUDY ON THE CORRELATION OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY WITH THE BANKS EFFICIENCY AND STABILITY. Corp. Own. Control. 2013, 10, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganushchak-Efimenko, L.; Shcherbak, V.; Nifatova, O. Assessing the effects of socially responsible strategic partnerships on building brand equity of integrated business structures in Ukraine. Oeconomia Copernic. 2018, 9, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoskova, K.; Krizanova, A. Comparison of selected internationally recognized brand valuation methods. Oeconomia Copernic. 2017, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, R.; Wahyudi, S.; Suharnomo, S. THE EFFECTS OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ON MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE: THE MEDIATING ROLE OF SOCIAL COLLABORATION AND GREEN INNOVATION. Versl- Teor. Ir Prakt. 2017, 18, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasylieva, T.; Leonov, S.; Lasukova, A. Evaluation of the banks corporate social responsibility concept implementation level. Econ. Ann. XXI 2014, 1–2, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva, T.A.; Leonov, S.V.; Lunyakov, O.V. Analysis of internal and external imbalances in the financial sector of ukraine’s economy. Actual Probl. Econ. 2013, 150, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Marcel, D.T.A. Impact of the Foreign Direct Investment on Economic growth in the Republic of Benin. Financ. Mark. Inst. Risks 2019, 3, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, S.V.; Vasylieva, T.A.; Tsyganyuk, D.L. Formalization of functional limitations in functioning of co-investment funds basing on comparative analysis of financial markets within FM CEEC. Actual Probl. Econ. 2012, 134, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vasylyeva, T.A.; Leonov, S.V.; Lunyakov, O.V. Countercyclical capital buffer as a macroprudential tool for regulation of the financial sector. Actual Probl. Econ. 2014, 158, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Skare, M.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Tracking financial cycles in ten transitional economies 2005–2018 using singular spectrum analysis (SSA) techniques. Equilibrium 2019, 14, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalilov, K.; Lyeonov, S.; Buriak, A. COMPARATIVE STUDIES OF RISK, CONCENTRATION AND EFFICIENCY IN TRANSITION ECONOMIES. Risk Gov. Control. Financ. Mark. Inst. 2015, 5, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendiukhov, I.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Managing innovations in sustainable economic growth. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2017, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikiene, D. Impact of environmental taxes on sustainable energy development in baltic states, Czech republic and Slovakia. E+M Èkon. A Manag. 2015, 18, 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dkhili, H. Environmental performance and institutions quality: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 3, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masharsky, A.; Azarenkova, G.; Oryekhova, K.; Yavorsky, S. Anti-crisis financial management on energy enterprises as a precondition of innovative conversion of the energy industry: Case of Ukraine. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 3, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Rashid, B. Influential Factors of Green Consciousness in Bangladesh: A Pragmatic Study on General Public in Dhaka City. Socioecon. Chall. 2019, 3, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vysochyna, A.V.; Samusevych, I.V.; Tykhenko, V.S. The effect of tax tools in environmental management on region’s financial potential. Actual Probl. Econ. 2015, 171, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hlaváček, P.; Janáček, J. The Influence of Foreign Direct Investment and Public Incentives on the Socio-Economic Development of Regions: An Empirical Study from the Czech Republic. E+M Èkon. A Manag. 2019, 22, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, P. Warsaw School of Economics Drivers of Green Supply Chain Initiatives and their Impact on Economic Performance of Firms: Evidence from Pakistan’s Manufacturing Sector. J. Compet. 2019, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dabija, D.; Bejan, B.M.; Dinu, V. How sustainability oriented is generationz in retail? A literature review. [Kiek mažmeninėje prekyboje į darną orientuota z karta? Literatūros apžvalga] Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sjaifuddin, S. Environmental management prospects of industrial area: A case study on Mcie, Indonesia. Versl- Teor. Ir Prakt. 2018, 19, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y.; Кuzmenko, Ð.; Boiko, A. Research on the impact of industry 4.0 on entrepreneurship in various countries worldwide. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2019: Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020, Granada, Spain, 10–11 April 2019; pp. 2373–2384. [Google Scholar]

- Bilan, Y.; Lyeonov, S.; Vasylieva, T.; Samusevych, Y. Does Tax Competition for Capital Define Entrepreneurship Trends in Eastern Europe? Line J. Model. New Eur. 2018, 2018, 34–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y.; Vasylieva, T.; Lyeonov, S.; Tiutiunyk, I. Shadow Economy and its Impact on Demand at the Investment Market of the Country. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyuchenko, N.; Starinskyi, M.; Tiutiunyk, I.; Kobushko, I. Methodical Approach to the Assessment of Risks Connected with the Legalization of the Proceeds of Crime. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2018, 14, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çerae, G.; Meço, M.; Çera, E.; Maloku, S. The effect of institutional constraints and business network on trust in government: An institutional perspective. Adm. Si Manag. Public 2019, 1, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivančiks, J.; Trofimovs, I.; Teivāns-Treinovskis, J. EVALUATIONS OF SECURITY MEASURES AND IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION ON CHARACTERISTICS OF PARTICULAR PROPERTY CRIMES. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2019, 8, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchenko, V.; Boyko, A.; Bozhenko, V.; Mynenko, S. MONEY LAUNDERING RISK IN DEVELOPING AND TRANSITIVE ECONOMIES: ANALYSIS OF CYCLIC COMPONENT OF TIME SERIES. Versl- Teor. Ir Prakt. 2019, 20, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarczyk, B. The Management Faculty, Czestochowa University of Technology, Czestochowa, Poland and North-West University, Faculty of Economic Sciences and IT, Vaal Triangle, South Africa Tax incentives as a main factor to attract foreign direct investments in Poland. Adm. Si Manag. Public 2018, 30, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Leonov, S.; Yarovenko, H.; Boiko, A.; Dotsenko, T. Prototyping of information system for monitoring banking transactions related to money laundering. Edp Sci. 2019, 65, 04013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oliinyk, V.; Kozmenko, S.; Wiebe, I.; Kozmenko, S. Optimal Control over the Process of Innovative Product Diffusion: The Case of Sony Corporation. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiliński, A. Mechanism of modernization of industrial sphere of industrial enterprise in accordance with requirements of the information economy. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 4, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Dharfizi, A.D. The energy sector and the internet of things – sustainable consumption and enhanced security through industrial revolution 4.0. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 14, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Ye, J.; Wang, P. Does the institutional environment affect the failed technological innovation in firms? evidence from listed companies in china’s pharmaceutical manufacturing industry. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani, M.; Zolfani, S.H.; Zavadskas, E.K. NEW INTEGRATION OF MCDM METHODS AND QFD IN THE SELECTION OF GREEN SUPPLIERS. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkočiūnienė, Z.O.; Miroshnychenko, O. TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: THE ROLE OF R&D SPILLOVERS IN INNOVATION DEVELOPMENT. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2019, 9, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, M.; Wach, K. What determines export structure in the EU countries? The use of gravity model in international trade based on the panel data for the years 1995–2015. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Stopa, M. Do SME’s innovation strategies influence their effectiveness of innovation? Some evidence from the case of Podkarpackie as peripheral region in Poland. Equilibrium 2019, 14, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T. Does Foreign Direct Investment Really Support Private Investment in an Emerging Economy? An Empirical Evidence in Vietnam. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2019, 15, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozmenko, O.; Poluliakhova, O.; Iastremska, O. Analysis of countries’ investment attractiveness in the field of tourism industry. Investig. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2015, 12, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M. The determinants and measurement of a country brand: The country brand strength index. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyulyov, O.; Chygryn, O.; Pimonenko, T. National brand as a marketing determinant of macroeconomic stability. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 3, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y.; Lyeonov, S.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. Brand management and macroeconomic stability of the country. [Zarządzanie marką i stabilność makroekonomiczna kraju]. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart-Gansiniec, R.; Sułkowski, Ł. Crowdsourcing—A New Paradigm of Organizational Learning of Public Organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowski, Ł.; Seliga, R.; Wozniak, A. Image and Brand Awareness in Universities in Consolidation Processes; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 608–615. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, P.; Honnery, D. Energy Efficiency or Conservation for Mitigating Climate Change? Energies 2019, 12, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magda, R.; Vasa, L. Economic aspects of natural resources and land usage. Folia Pomeranae Universitatis Technologiae Stetinensis. Oeconomica 2012, 69, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).