1. Introduction

Climate change is already causing frequent and more intense wildfires, droughts, and tropical storms, as the 2018 report of the International Panel of Climate Change makes clear. In the absence of rapid and radical mitigation action, climate change impacts may well be catastrophic in the longer term [

1]. Accordingly, a rapid transition to low carbon energy is required. Such a transition is particularly important in Asia, the region with the world’s highest projected carbon emissions and in which an estimated 92 percent of the world’s proposed coal-fired power plants are anticipated to be built.

However, mitigating climate change must be seen in its broader context and in conjunction with two other energy objectives. The first is mitigating energy poverty, defined in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 7) as access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable modern energy. In Asia, energy poverty is widespread: around 319 million people remain without electricity access, many of them living in geographically isolated areas and remote places where an electricity grid is unlikely to ever reach [

2]. The second objective is energy security, which, in broad terms, means having a reliable and adequate supply of energy at reasonable prices and includes the availability of fuel reserves, the ability of the economy to acquire supply to meet projected energy demand and the extent to which the economy has a diverse range of energy sources or in which end users can become self-sufficient [

3].

In Indonesia, the largest economy in Southeast Asia, the destruction of carbon sinks—primarily forests and carbon rich peatlands—has been the biggest contributor to its carbon footprint. However, in the future, this will be substantially exceeded by the energy sector [

4]. The latter’s carbon emissions, on current projections, will escalate by 80 percent by 2030 as both the population and the economy expand rapidly [

5]. Achieving Indonesia’s climate mitigation aspirations and, in particular, its commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement, will require rapid adoption of renewable energy for power generation. Within Indonesia, nearly 25 million people still lack access to electricity, many on outlying islands or other remote areas where logistical problems, and a sparsely distributed population preclude grid-based solutions [

6].

Until recently, diesel generators have been viewed as a standard rural electrification solution. However, with Indonesia’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions and meet its Paris Climate Agreement target, such generators, too, become far less attractive. An opportunity now exists in such remote areas to achieve the triple goals of reducing energy poverty, ensuring energy security, and mitigating climate change by leapfrogging fossil fuel based energy solutions and embracing technologically advanced and increasingly cheap renewables technology (i.e., zero-carbon electricity expansion).

However, here, a major obstacle becomes apparent, namely that providing solar or wind-based power on any scale, like other low carbon initiatives, requires considerable amounts of finance. Public finance and overseas development aid are significant, but a large gap will still exist between what they can deliver and what is needed even if they are increased. Therefore, mobilizing private climate finance for renewable energy generation to scale will be crucial in enabling Indonesia to meet its renewable energy goal and provide electricity access to those living in energy poverty.

Accordingly, this article’s concern is with privately financing renewable energy and mitigating energy poverty on such islands and in other remote areas. In particular, it addresses compelling policy and governance questions: What are barriers to mobilize private climate finance to support renewable energy uptake for rural electrification? What are the implications of these challenges to mitigate the energy trilemma? Under what conditions might the mobilization of private climate finance be best realized to address energy poverty, while at the same time mitigating climate change and ensuring energy security?

This article argues that deploying renewable energy sources in outlying islands and other remote areas where much of the population has limited access to electricity could present an opportunity for a remarkable complementarity between energy security, energy access, and climate change mitigation in Indonesia. Here, mobilizing private climate finance is an essential vehicle for achieving complementarity between the three key energy objectives in renewable rural electrification. However, multiple barriers persist, leading to difficulties in managing the tensions of three key energy objectives and failure to reach the complementarity.

The article proceeds, as follows.

Section 2 describes the research methodology.

Section 3 reviews the literature on managing the energy trilemma and climate finance and lays out the empirical background of the power sector and of renewable energy policy in Indonesia, with a focus on rural electrification. This is followed by a discussion of three key obstacles to mobilizing private climate finance for the rapid deployment of renewable energy sources within outlying and remote areas and the implications for managing the energy trilemma.

Section 5 concludes and suggests ways to move forward.

2. Methods

The analysis that is presented here is based on data collected during fieldwork in Indonesia undertaken during February–April 2019. In principle, the field research activities consisted of two main activities: first, semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in renewable energy and climate finance in the national and sub-national levels. Purposive sampling was used to capture the network of actors that engaged in policy and initiatives related to renewable energy and climate finance in the country [

7]. Initial informants were identified while using publicly available information concerning energy and climate finance stakeholders, together with my professional networks. We then asked to identify other key stakeholders through a process of snowball sampling. These key stakeholders include: national/local policy makers, banking/finance institutions, renewable energy developers, NGOs/research institutions, and community representatives. A total of 40 interviews were conducted. The interviews generally lasted from 30 minutes or more, depending on how much time the participants’ willingness to express their views.

Key informants were asked about their perceptions concerning main barriers to, and opportunities for, mobilizing private climate finance for an energy transition in Indonesia, the effectiveness of existing policy measures to address energy poverty through renewable energy sources, and further reforms needed to overcome the barriers. Specific questions were asked of private sector actors about their experiences in accessing finance to develop renewable energy projects and about the challenges that they encounter in doing so. The interview data were coded and analyzed to identify emerging themes and key ideas particularly related to barriers and opportunities for mobilizing private climate finance and exploring their connections, (in) consistencies and contradictions [

7,

8]. These include clustering the findings into three key barriers (see

Section 4).

Second, field observation was carried out to have a closer look on the implementation of renewable energy projects in Sumba Island, Nusa Tenggara Timur. Sumba Island, located in Nusa Tenggara Timur Province, is one of the islands with the lowest electrification rate in the country. Less than a quarter of its population, approximately 650,000 people, had access to electricity in 2010. In that year, the Indonesian government, in close collaboration with the International NGO, HIVOS, launched the Sumba Iconic Island program, with a target of increasing the electrification ratio by 95 percent by 2020 while using renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, micro hydro power, and other sources [

9]. This plan relies on the mobilization of private climate finance and private sector participation in renewable energy generation due to limited public budget.

The qualitative interviews and field observation were complemented by a detailed analysis of government documents, including policy and regulations, media and other articles on renewable rural electrification, and climate finance for supporting energy transitions in Indonesia to gauge whether or to what extent these either enabled or hindered the goal of addressing energy poverty and address justice issues. The collected data sets were analyzed while using qualitative methods of content analysis, grounded theory, and discourse analysis [

10].

4. Findings and Discussion

Drawing on the analysis of the interview data and relevant documents, this section discusses key barriers for mobilizing private climate finance to support renewable rural electrification and the implication to achieve three key energy objectives.

4.1. Barriers to Achieve the Complementarity of Three Key Energy Objectives

4.1.1. Regulatory Uncertainty and Institutional Barrier

In Indonesia, there are multiple regulatory and institutional barriers to renewable energy expansion in outlying areas. Almost all of the key informants interviewed suggest that regulatory uncertainty is one of the main obstacles to mobilizing private climate finance for renewable rural electrification. Regulatory frameworks to facilitate renewable energy uptake continually change and are often inconsistent. The resulting regulatory uncertainty increases the costs for project developers, both in terms of the investment of time necessary to understand the implications of new regulations and in the cost of complying with them.

Changes in government policy and priorities frequently flow from changes in leadership at the ministerial level. As described earlier, the 2017 leadership change in the MEMR has altered the renewable energy orientation from state support of renewable energy to a focus on price affordability, underpinned by regulation MEMR 50/2017. The new regulation stipulates that, with the exception of geothermal and hydropower, renewable energy sources are subject to a price cap of 85 percent of the electricity generation cost (Biaya Produksi Pembangkitan/BPP) if it is higher than the national generation cost. This regulation is widely regarded as discriminatory against renewable sources as non-subsidized renewable energy must compete with subsidized fossil fuel power generation. Further, the regulations on FITs/ceiling price have also been dismantled under the new energy policy regime. The changes in the regulatory frameworks, far from mobilizing private climate finance, have been counter-productive to that aspiration.

Fluctuating decentralization policies have also been named by key informants as an obstacle to renewable rural electrification. Under Law 32/2004 on decentralization, district governments have been given the rights and responsibilities to issue concessions and licenses for renewable energy. However, in the revised regulation (Law 23/2014, revised with Law 23/2015), which took into effect in 2017, such authority has been transferred back to the provincial government. Such unpredictable regulatory change has created an inhospitable environment for private investment. The 2017 regulatory changes have also prevented the district government from allocating a budget for subsidizing the maintenance of renewable power plants. On Sumba Island, around 63 percent of renewable energy facilities using renewable energy are no longer operating as a consequence of the lack of institutional and budgetary support [

38]. According to a local government officer [

39],

“We were so enthusiastic with the program [Sumba Iconic Island] but the Law 23 [Decentralization Law 23/2014] was revised, hence the district government no longer has the authority in the energy sector. It is in the provincial government’s hands now. Therefore, it is hard for us to allocate budget for renewable energy development and maintenance because it is not our domain to do that.”

While standardized power purchase agreements (PPAs) can create a conducive investment climate and thereby attract IPPs, in the current regulatory framework, each PPA needs to be directly negotiated with PLN. Given PLN’s recalcitrance, in this regard, many potential PPAs are stillborn. A 2018 report suggests that some projects have been held up for years due to difficulties in the negotiating PPAs [

31]. Moreover, some PPA negotiations have been terminated as a result of the policy change on feed-in tariffs, which removed the incentives that would otherwise have made them viable [

40].

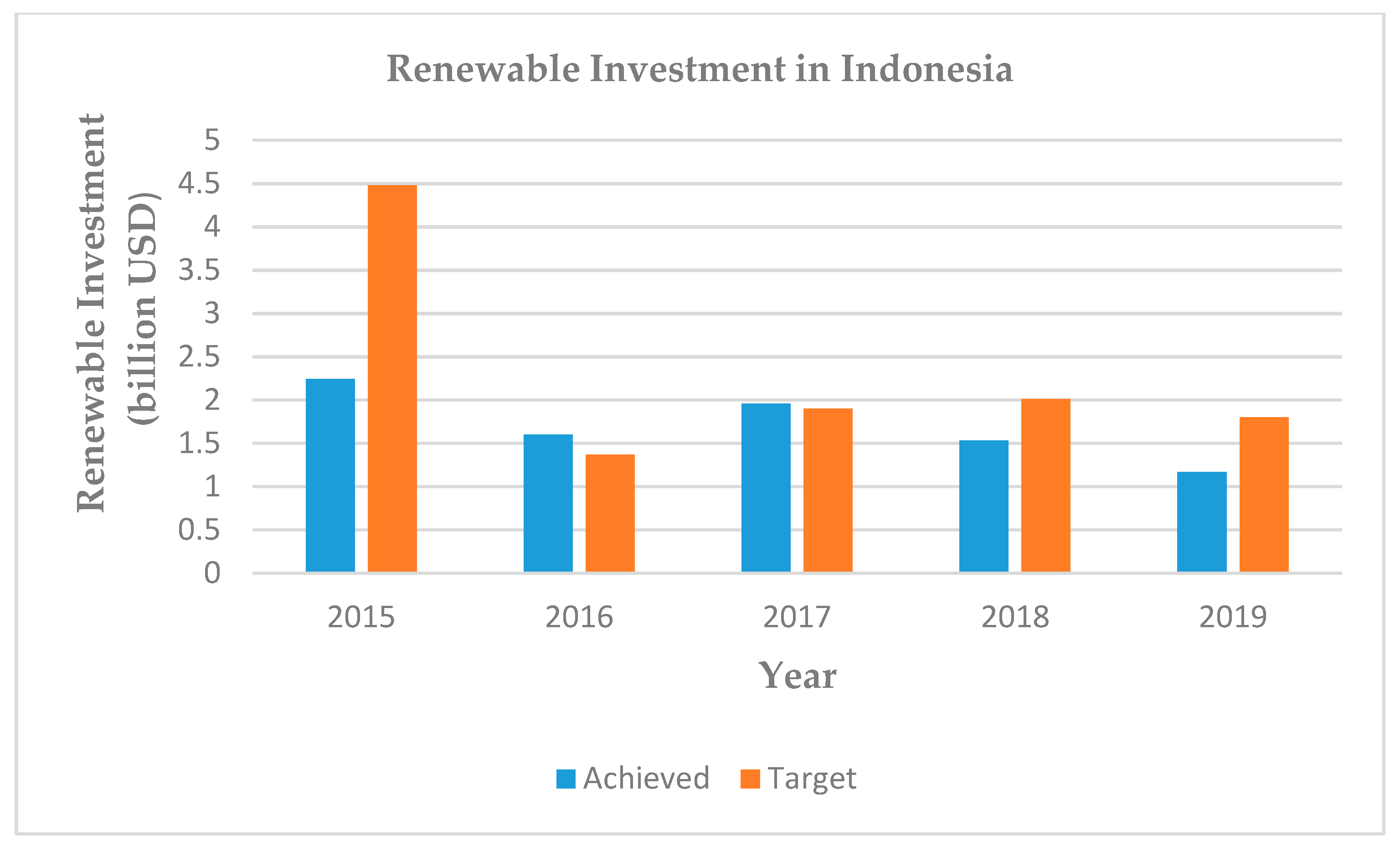

This regulatory uncertainty has had a chilling effect on private sector investment in the renewable energy sector. At best, it has stalled privately funded renewables projects and prompted private climate finance to adopt a “wait and see” strategy [

31,

41]. This is reflected in the declining amount of investment for renewable energy over the years, as described in

Figure 2 [

42]. On Sumba Island, many investors had pulled out by 2018 despite initial pipeline projects for renewable energy and early signs of investor interest [

43]. The regulatory change has resulted in most private sector renewables investors being unable to secure PPAs, which led them to abandon their investment plans on the island. The policy change has also caused substantial project delays and stalled some pipeline projects.

Moreover, the monopolistic nature of PLN has hampered private sector development and crowded out private investment in the sector. There have been waves of regulatory measures to push for electricity restructuring, particularly for providing broader space for independent power producers (IPPs) to build power plants, including those for renewable sources. Notwithstanding these measures, active resistance from PLN to the inclusion of private sector participation has resulted in decades of policy and regulatory instability in the electricity sector [

6,

14], which, in turn, discourages private investment.

The current procurement and bidding processes for renewable energy projects are also deemed to be unclear due to lack of transparency and insufficient predictability; this has created a major constraint to investment. All private companies that wish to participate in the bidding process need to be listed in a registry that was established by PLN through a lengthy and unclear screening process. A key informant suggests that such a process has screened out most domestic and small-scale private companies with limited capital and experience in implementing renewable energy projects (despite some of them being technically advanced). As described by a private sector informant [

44],

“We are really frustrated with the lack of transparency and commitment of PLN…No advocacy for the private sector involvement in electricity sector. Private sectors are the last persons you want to collaborate with. That is always that kind of sentiment [of resources nationalism]. With the monopoly, they [PLN] can make their own decision without any consultation.”

PLN has also exerted its control over the power sector by prioritizing the grid extension network. PLN insists on extending the grid to these areas notwithstanding ample opportunities for using off-grid renewable systems for rural electrification, which is often more expensive than off-grid solutions. On Sumba Island, for instance, although the government is committed to electrify the island with 100 percent renewable energy sources, the results have been mixed at best. While there has been a substantial increase in the electrification rate, reaching over 50.9 percent by early 2018, only 20.9 percent comes from renewable energy sources [

38].

Due to Indonesia’s archipelagic geography, decentralized mini-grid and off grid electrification has been considered to be more appropriate than grid extension, especially in remote and rural areas (Schmidt et al., 2013). However, engaging IPPs to provide off-grid renewable electricity generation remains difficult, particularly due to regulatory barriers. Law 30/2009 on electricity generation stipulates that PLN’s business area covers all areas in Indonesia. As a consequence, all private entities who wish to participate in the power business will need to either secure a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with PLN (for on grid electricity generation) or obtain a permit from the government in coordination with PLN, in which PLN will need to release a particular area from their business jurisdiction (for off grid electricity generation).

The business process for setting up off grid electricity generation is considered to be more difficult than on-grid electricity generation [

40,

45,

46]. A key informant suggests that PLN remains reluctant to release its business area for off grid renewable energy projects [

46]:

“They need to deal with PLN to agree releasing the business area. If PLN disagrees, and most of the case that’s what happens, it’s going to ruin the whole plan for off-grid electricity business.”

Even when the PLN agrees to relinquish a particular area for off grid renewable energy, another problem arises, as the tariff for electricity needs to be approved by the provincial government. However, in most cases, the provincial governors will not take any political risks by approving an electricity tariff above the highly subsidized PLN tariff. This political consideration prevents politicians from embracing renewable energy sources notwithstanding the technological advancement that makes adopting the renewables to be economically more sensible. As a result, most private sector businesses interviewed view investing in on grid electricity generation as more likely to reap dividends than investing in off grid projects, although even the former is beset with regulatory challenges.

4.1.2. Limited Financial Access and Options for Small Scale and Distributed Renewable Energy

Financial options for renewable rural electrification are scarce, especially for small scale and distributed renewable energy projects in Indonesia. Key informants suggest that access to finance for large scale renewable projects is easier due to the greater availability that such projects have to attract finance from both international and domestic sources. On the supply side, there is also a high appetite for investment in renewable energy projects, especially from international financial investors, but only for substantial projects. However, small-scale renewable energy projects typically have to rely on a limited range of domestic financial sources. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the Indonesian financial market is relatively small and dominated by a banking sector that typically relies on short-term deposits to fund its lending operations. The average loan tenor of Indonesian banks is only eight years, but renewable energy investment generally requires funding over a much longer term.

Access to finance by renewable energy companies that are small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) is even more challenging due to onerous collateral requirements. Such enterprises are usually required to provide 120 percent collateral from the total loan obtained and to have a creditworthy sponsor. As one key informant suggested, “For [renewable energy] project under 10 MW, it’s hard to get the bank loan. Because the project developers are required to provide 120 percent collateral from total loan requested” [

46].

The banking sector is reluctant to provide for longer loan tenors or less onerous collateral requirements, because of the perception that renewable energy projects, particularly those involving SMEs, are high risk—a perception that is reinforced by the unpredictability and changing nature of government regulation [

28]. Even so, local banks may well have an exaggerated impression of the risks that are involved because of a lack of capacity and experience in this sphere. The consequence is to influence financing costs, the availability of capital, and the overall viability of projects.

A further impediment for SMEs is that the MEMR Regulation 50/2017 requires all types of renewables to follow the Build, Own, Operate, and Transfer (BOOT) scheme, under which power plant assets cannot be used as collateral. This creates another challenge for small IPPs, as they do not have other assets that are capable of being used as collateral. Further, the current regulatory framework also fails to distinguish the scale of investment. As a consequence, the amount of time and costs is similar, regardless of the scale of investment.

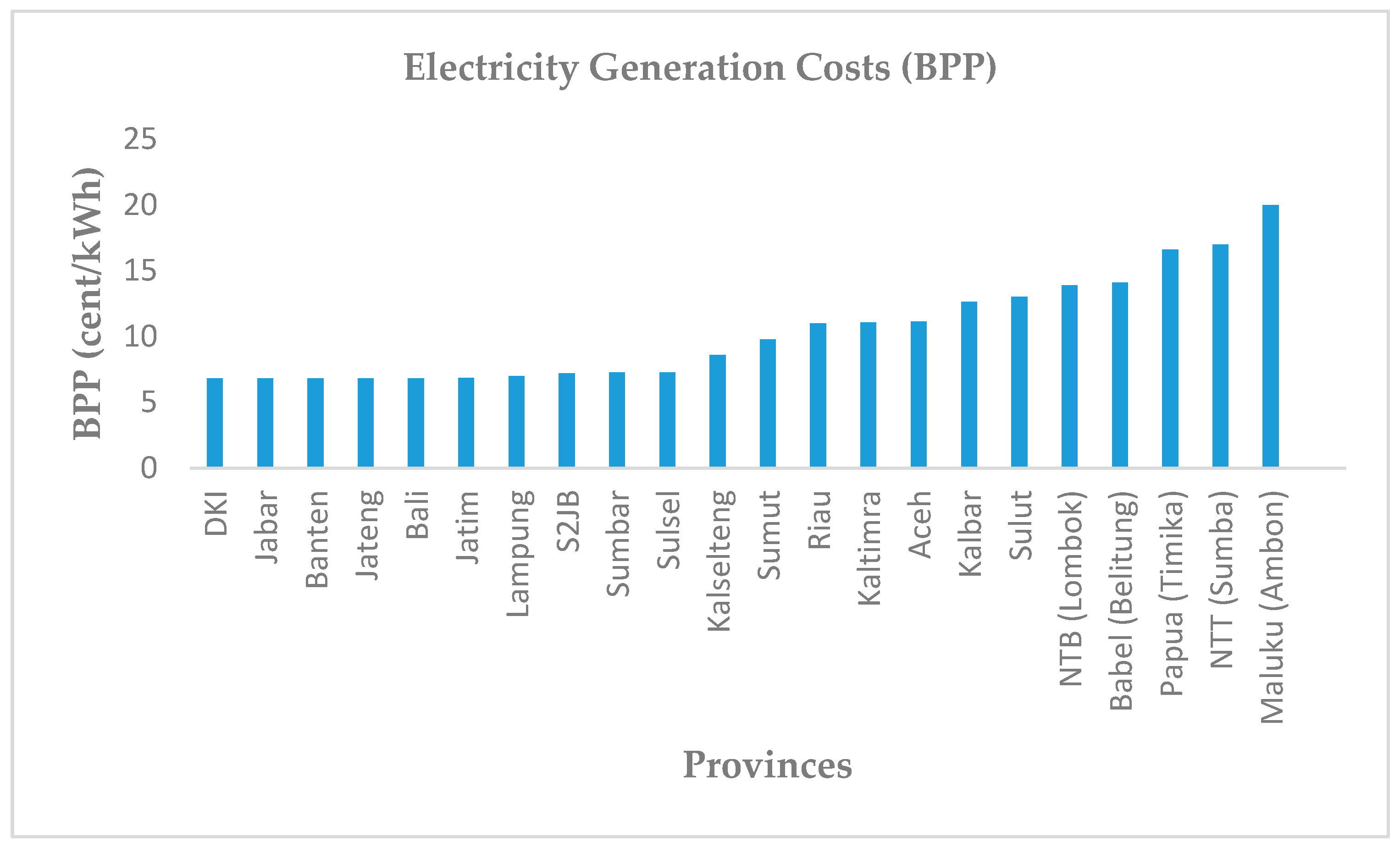

Inefficient renewable energy pricing design has also skewed the risk-return profile of renewable energy projects, making it more challenging to put together a bankable project. The regulation MEMR 50/2017 establishes a price cap for renewable energy and sets geographically differentiated price structures to provide incentives for renewable energy investments in areas with low electrification rates and high energy costs. For instance, the lowest electricity price is set USD 6.81 cent/kWh in Java and Bali area (with some exceptions), while the highest price is set for USD 20 cent/kWh in eastern part of Indonesia and outlying islands, as described in an implementing regulation, MEMR Regulation 1772 K/20/MEM/2018 (see

Figure 3). This strategy purports to ensure the mobilization of financial investments in renewable energy in areas that otherwise would not be attractive for such an investment, hence addressing the energy justice issue. As described by a key informant [

47].

We designed this regulation [MEMR Regulation 50/2017] to make sure the private sector would be willing to invest in areas with low electrification, especially in the eastern part of Indonesia. This is a test for investors; we want to encourage them to not just focus on big scale projects with big consumer demand. We encourage them to invest in the areas with low electrification ratio and poor infrastructure, where smaller scale investment is needed. They actually still can get profit with the current price structure.

However, private sector informants suggest that the geographically differentiated price structure and price cap for renewables that are introduced in the regulation have discouraged them from investing as the price is deemed too low for the developers to earn a reasonable profit and recover their investment. Consequently, only developers who wish to develop projects need to do so at a significant scale and bring cost under the regulated price and make a reasonable investment return. Consequently, most private investment has been focused on large scale projects in densely populated areas. A key informant suggests [

48],

“Everything is good for us as long we have big scale projects. Give me 100 or 150 MG, I can do that…You need to have the scale that is important for the low price. You need the revenue to cover the cost.”

Overall, the consequence of the current regulatory regime is to impose substantial obstacles on SMEs seeking finance for rural electrification projects, both by making them too costly to be viable and by cutting off viable sources of finance. In terms of the latter, key informants from banking and financial institutions suggest factors shaping their investment decisions include project feasibility and cost, rate of return, and the credibility of project developers. Oftentimes, using these factors to evaluate project feasibility results in the local banks opting to invest in fossil fuel power generation rather than in renewables, as described by a key informant [

49],

“For electricity, 70 percent of electricity generation comes from coal in Indonesia. Coal is indeed still the cheapest energy source here…Indonesia is an emerging market so it’s understandable that we prioritize cheap and affordable energy sources. For us, rate of return is important and coal fired power plants offer a cheaper price for PLN which generates high return.”

The core metric for evaluating project viability remains project bankability, which refers to the capacity to generate an estimated level of profit that fulfils the lender requirements [

50]. Consequently, most of those who are able to access renewable energy finance are large companies that have credibility in implementing large-scale projects. This finding reaffirms studies [

6,

50] that show that the focus on project bankability has severely disadvantaged SMEs and that most renewable energy projects that have been successful in obtaining funding are large scale projects in areas with relatively high installed capacity.

4.1.3. Barriers Presented by Geography

With an area that covers more than 17,000 islands, Indonesia encounters unique challenges in designing, constructing, and operating its electricity network. Indonesia will continue using a diversity of large, small, and off-grid electricity systems in the near future because of this archipelagic geography. Providing electricity to such locations could be an expensive undertaking due to logistical issues, long distance travel, poor infrastructure, and a fragmented distribution network [

17,

50]. The private sector often needs to factor in the costs of improving infrastructure to build the renewable energy facilities, and it sometimes invests significant resources in the project without having firm financial arrangements in place. As suggested by a private sector informant [

48],

“We need to provide a lot of money into the project to get it ready; we don’t wait for everything to get it done. We do the logistics, the environmental assessment and land acquisition without PPA. We start building roads and build up concrete without financial close from the equity. We do a lot of things based on the faith that our project is a good project.”

Operation and maintenance can be costly due to the remoteness of these places. On Sumba Island, out of 9.8 MW installed capacity, only 37 percent is still operating or partially operating due to the lack of maintenance support [

38]. Key informants attributed this to the lack of financial support and local capacity to maintain facilities. The low education level in many rural areas also presents a barrier for renewable energy facilities [

40,

51].

Estimating energy demands in these locations is particularly challenging because of diversity of rural communities in terms of population distribution, cultural, and social structure. A key informant suggests that the unavailability of reliable data compiled by relevant government agencies capable of identifying whether or to what extent a rural population experiences energy poverty means that there is no ready basis for identifying relative need and setting priorities for electrification [

46]. It is equally difficult to forecast the energy demands of rural areas and estimate the financial costs needed for investment. These challenges need to be properly understood by the private sector and integrated into project costing to determine whether a proposed project is likely to generate a reasonable investment return.

Sustaining renewable energy plants is also deemed challenging in the context of rural electrification [

52,

53,

54]. Rural electrification projects are often based on the premise that they could stimulate local economic growth and alleviate poverty, with their access to electricity providing new economic opportunities. Indeed, some studies have suggested that renewable rural electrification should be valued as much for its capacity to improve the local development rates as for its capacity to alleviate energy poverty [

17,

52]. Harnessing new economic opportunities would also enable rural communities to pay for the electricity that is provided, hence increasing the likely viability of the initial energy investment. However, this will not necessarily be the case. For example, one key informant suggested that there would be a significant time lag between the installation of rural electrification and any flow on economic advantage, and those advantages could not be taken for granted. On the contrary, economic development would depend upon other factors, such as the provision of necessary supports for local productive activities.

4.2. Implications for Managing the Energy Trilemma

While mitigating energy poverty has been an important social goal in the past, today energy poverty must be addressed in ways that also mitigate climate change and address energy security. Policy makers are increasingly looking to alleviate energy poverty (i.e., lack of access to electricity) by means other than burning fossil fuel and, in particular, by harnessing various forms of renewable energy, given the dire warnings that humanity is pushing close to the tipping point beyond which dangerous climate change becomes inevitable. There is a particularly compelling case for precisely such a solution when it comes to providing electricity to those who live in rural, and especially remote, areas, and who currently experience energy poverty.

In any event, solutions that might have appeared to be economically rational in the past may no longer have that characteristic because of technological change. Renewable energy technologies in general and solar PV technology in particular have advanced rapidly, and the price of solar panels has plummeted over the last decade [

55]. For instance, the global average electricity cost of solar PV has fallen to the extent that, in many locations, it has passed the ‘economic tipping point’ [

56] at which the adoption of this technology is the most cost-effective option for rural electrification and for reducing energy poverty.

Harnessing private climate finance is crucial in facilitating the adoption of low carbon technologies for rural electrification. However, some challenges persist that constrain the options for managing tensions between the three horns of energy trilemma and distort economics and technical viability of renewable energy, as described in the previous section.

The monopolistic nature of the electricity landscape has created limited and inefficient electricity markets that lead a predictable crowding out effect. This situation is exacerbated with PLN’s deep commitment to fossil fuel-based power generation and resistance to change, which resulted in the relentless promotion of fossil fuel-based power for rural electrification. Further, conflict of interest within PLN hampers the penetration of private investment in renewable energy. For instance, PLN’s role as a fuel supplier for diesel generators has inclined PLN to retain diesel-based power generation in rural areas [

31], notwithstanding the economic and environmental benefits of a switch to renewables. This trend is apparent on Sumba Island, where diesel-based power far exceeds that provided by renewables despite an in-principle commitment to electrify the island entirely using renewable energy sources.

While utilizing diesel-based generators for rural electrification could address energy poverty and arguably contribute to energy security in the short term, it could lead to energy insecurity in the long term. The reason to continue deploying fossil fuel-based power generation, particularly diesel generators, for rural electrification is often attributed to the availability, reliability, scalability, and relatively low upfront cost [

17,

57]. However, maintaining a stable and cost-effective supply of diesel generators requires substantial government subsidy. This has led the state utility company struggle to keep up with the energy demands, particularly in geographically isolated and rural areas, as the price to provide diesel generators in these areas could soar. Further, it could expose rural communities with fossil fuel price volatility. Crucially, it also does not address climate change mitigation.

This energy insecurity also has implications for the inability to address energy poverty. As we have seen, current regulatory frameworks and available financial options are skewed in favor of fossil fuel plants and, to a lesser extent, large scale renewable energy projects. Hence, most financial investment flows to large-scale projects with more attractive investment returns. As a consequence, small scale projects—particularly those aimed at addressing energy poverty in rural areas—are often deemed to be economically infeasible. Thus, such an approach does little, if anything, to address the energy poverty problem, especially in geographically isolated areas and outlying islands where small scale and distributed renewable energy technologies are more appropriate than the large scale and centralized ones. The result is that the geographic inequalities in access to electricity have barely been addressed.

In terms of climate mitigation, there is an apparent mismatch between Indonesia’s ambitious commitments to carbon emission reductions under the Paris Agreement and domestic policies, many of which are likely to make Indonesia’s Paris targets unattainable. In the energy sector, the current regulatory frameworks narrowly interpret energy security in terms of price affordability and impose a price cap for the renewable. It has created an uneven playing field, in which renewable energy technologies, in particular solar PV and wind, are unable to compete, not because they are inherently more expensive than fossil fuels, but simply because fossil fuel generators benefit from substantial subsidies. Currently, the coal industries continue to receive substantial government support in term of loan, tax exemption, and price supports [

58]. These industries will also continue to benefit from increasing domestic consumption, as the current PLN’s business plan includes a significant increase of the establishment of coal power plants [

16]. Moreover, no premium will be paid to recognize the benefits of renewable energy to mitigate climate change. Compounding this problem, domestic demands of cheap electricity, regardless of the environmental consequences that it could generate, have led policy makers and politicians to persistently incline to policies that are in favor of fossil fuel power generation, particularly coal. Further, vested political interests and rent seeking in fossil fuel industries, particularly coal, continue to shape decision making processes in the power sector. This has slowed the achievement of the energy mix target and could ultimately lock Indonesia into a high carbon economy.

Therefore, it is not surprising that Indonesia has been categorized as a low performing country in addressing climate change in the latest climate change performance index, an instrument that evaluates and compares the climate protection. It is ranked 39 out of 58 countries and the European Union [

59]. In terms of renewable energy, Indonesia is also rated low, due to the absence of an effective mechanism to support the renewables, resulting in low uptake in the renewable energy technologies.

5. Conclusions

Managing the trade-off between energy poverty, energy security, and climate change mitigation has frequently proved to be an intractable energy policy challenge in Indonesia. Using low carbon technology to address energy poverty in remote areas could serve as the case, where, exceptionally, no trade-off is necessary because a complementarity between three key energy objectives can be achieved. The aspiration is to ameliorate energy poverty using low carbon solutions (thus mitigating climate change) while also enabling the population in these areas to be self-sufficient in electricity generation and distribution, hence addressing energy security. This, in turn, could assist Indonesia to achieve the SDG 7 target to ensure access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable modern energy.

However, overcoming, or at least mitigating, the energy trilemma is not easy. Multiple serious obstacles constrain any rapid transition to the deployment of renewable energy sources on outlying islands and other remote areas, as the findings of this research suggest. These are of three key types. First, there are multiple regulatory and institutional barriers to renewable energy expansion in outlying areas including regulatory uncertainty, fluctuating decentralization processes, the recalcitrance of the monopoly energy provider PLN, and its unwillingness to facilitate standardized power purchase agreements (PPAs) and its capacity to crowd out private investment in the sector. Second, limited access to finance and limited financial options for small scale renewable energy projects hinders private climate investment. Pricing mechanisms that benefit mega-scale infrastructure development and disadvantage small scale/distributed grids are further impediments in mitigating the energy trilemma. Compounding this challenge is a geographical barrier that hampers economic viability and the sustainability of renewable energy initiatives.

Mobilizing private climate finance is an essential vehicle for achieving complementarity between the three key energy objectives in renewable rural electrification, and interviews with key stakeholders confirm that its absence is one of the most important and persistent barriers to advancing renewable energy in rural areas. Therefore, a rapid acceleration in the rate of renewable energy uptake can only be achieved with the introduction of very different regulatory and policy initiatives, being unpinned by mechanisms that enable greater access to private sector finance and are capable of overcoming impediments to generating it. Accordingly, what will be the ways forward to overcome the barriers?

First, predictability and certainty in the regulatory environment is paramount in achieving any national renewable energy target. Studies suggest that the certainty in the regulatory environment and effective enforcement of supportive regulatory frameworks that facilitate renewable energy uptake are necessary conditions for stimulating the mobilization of private climate finance [

22,

60,

61]. Here, the central government plays a crucial role, not only by asserting its long-term commitment to a low carbon transition, but also by designing and implementing a comprehensive, definitive and overarching regulatory framework consistent with the commitment. It will, in turn, increase the confidence of private climate finance to invest in the renewable energy sector.

Second, actions to reform misaligned policies and address structural barriers are crucial in mobilizing finance to support the transition to low carbon energy. These actions could include an unbundling of the monopoly power provider’s control over generation, retail, and distribution; sequencing policy instruments; providing mechanisms to incentivize private sector investment; and, facilitating market entry by independent power producers [

62]. Indeed, private sector participation will likely occur if there is an efficient electricity market and, if appropriate, financing is established. However, political barriers might continue to constrain energy sector reform in Indonesia. For instance, resistance to efforts to restructure the state electricity company through the introduction of Law 22/2002 on Electricity resulted in the law’s annulment by the Supreme Court for violating the constitution [

14]. Many reforms may be stillborn in the absence of political leadership.

Specific regulations and business processes are needed to stimulate private investment for small scale and distributed renewable energy technology. The current regulatory framework that does not distinguish the scale of investment and fails to recognize that small scale projects, irrespective of how beneficial they might be will be disadvantaged because of the disproportionate amount of time and the costs needed for small scale investment. Indonesia could learn from other countries, such as Cambodia and India, which have adopted ‘light-handed regulation’ to attract private investment in small and medium scale renewable energy projects [

63]. For example, in India, the Electricity Act allows for tariff setting based on negotiation between developers and customers and exempts mini-grids from licensing.

Third, establish mechanisms to address the challenges of financing renewable rural electrification. These could include incentivizing price mechanisms, implementing tax reform, and steering public financial instruments to overcome financial barriers to help with unlocking private capital, particularly to address critical early development risks of renewable energy projects [

28,

31]. The private sector needs to be provided with incentives and resources to extend electricity grids to a rural area, which implies a revision of current electricity tariffs and subsidies.

Moreover, it is essential to design and implement energy policy that encourages financial heterogeneity, as renewable rural electrification will likely require mixes of financial sources, including from the state, commercial, philanthropic, and other financial sources. While considering the nature of remoteness, a sparsely distributed population and the high initial cost of renewable energy development, financing renewable rural electrification will need the mobilization of financial sources beyond mainstream commercial lending that is exclusively structured by risk and return calculus and bankability consideration. As this research has shown, such a consideration has marginalized small and distributed renewable energy initiatives to obtain financial support. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that relying on homogenous financial sources could put energy transition at risk of boom and bust investment cycles [

64,

65]. Thus, innovative financing schemes will need to be developed, which are designed to support small scale and distributed renewable energy projects. Currently, policy makers in Indonesia are actively seeking to develop a financing scheme dedicated to supporting renewable energy uptake, the Energy Resilience Fund, for the purpose of mobilizing and combining different financial resources for renewable rural electrification. However, it remains unclear whether any such proposal would find support from key stakeholders, not least, PLN.

In Indonesia, there are some signs that suggest the emergence of a more benign investment environment for renewables. In particular, the government is exploring innovative approaches to harness private investments in green infrastructure, developing a roadmap for sustainable finance, which includes designing measures to encourage green lending and improve the resilience and competitiveness of national financial service institutions [

66,

67]. Moreover, several financial schemes also start to emerge, such as green bonds and blended finance. Green bonds, a financial debt instrument that requires the bonds to be invested in projects that generate environmental benefits, offer a promising pathway for increasing the flow of capital to green projects, including renewable energy projects [

68]. In 2018, for instance, Indonesia became the first country in the world to issue sovereign sukuk green bonds to fund green infrastructure projects, such as renewable energy, green tourism, energy efficiency, and waste management. The Indonesian government has used blended finance - an approach that mixes private, public, philanthropic and developmental sources of capital—for financing projects to attain sustainable development goals (SDG) under ‘SDG One’ initiative. However, whether and to what extent these financial schemes have been utilized for renewable rural electrification has yet to be investigated in this study. Therefore, future studies are needed to understand how, and to what extent, these emerging financial schemes have facilitated transition to low carbon energy and address the three key energy objectives in the country.