1. Introduction

The issues of sustainability in maritime transport and logistics services have been considered in terms of environment, economy, and society. Recently, a substantial amount of research has been conducted on the improvement of energy efficiency and the use of cutting-edge technology [

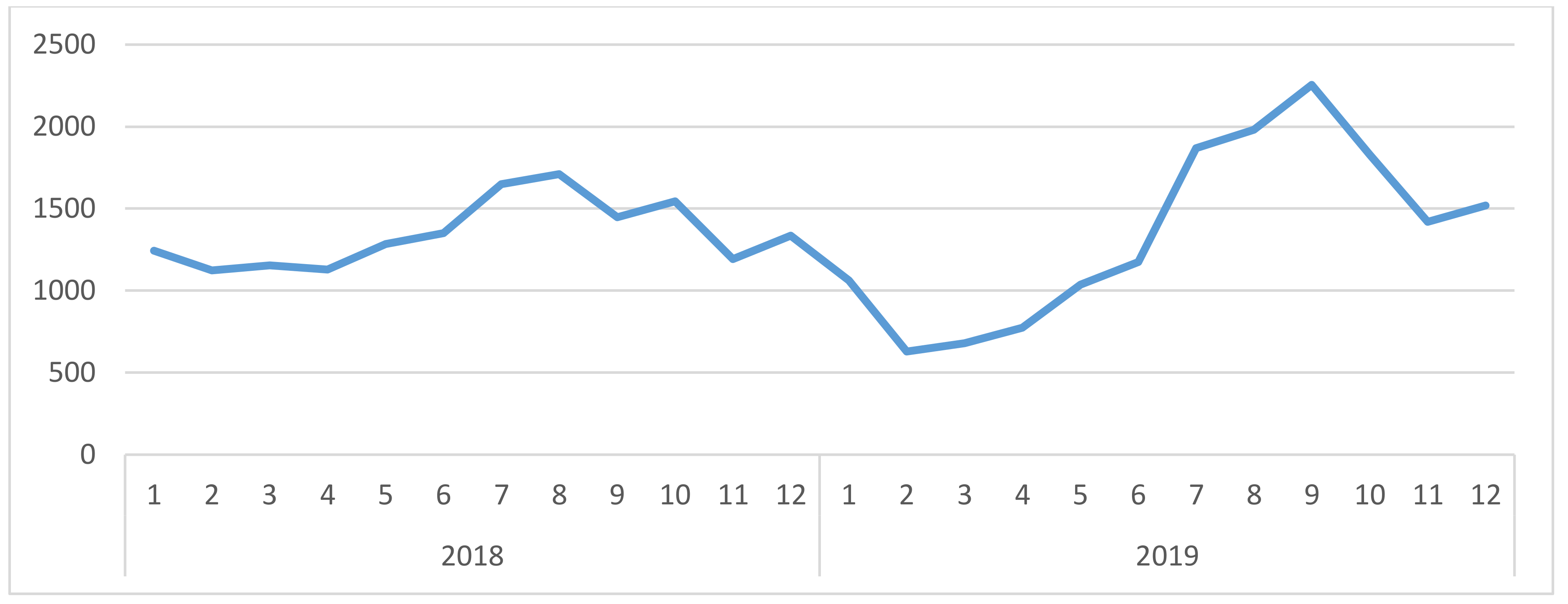

1]. While there are many concerns about the ongoing US–China trade conflict and the proliferation of global protectionism, in-depth research is lacking. Trade volume and maritime logistics services are closely linked, and sea freight prices have fluctuated widely since January 2018, as illustrated by the trend of the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) in

Figure 1. The BDI is a shipping cost index, which is used to be a leading indicator of future economic growth.

The Trump administration has denied the appointment of new judges for the Appellate Body, which is the WTO’s Supreme Court. The Supreme Court was closed on 11 December 2019, and this caused the WTO to face an existential crisis. [

2]. This means that the WTO cannot impose sanctions on any country which violates the WTO rules. The US’ WTO paralysis is directly related to trade sanctions against China.

What would be the impact on international trade and maritime logistics if the US continues to push the “decoupling” strategy against China and the WTO’s ability to govern the world trade ceased? Imposing new tariffs on China is a clear violation of the WTO rules, but the US is not concerned about the WTO rules, because the Appellate Body has stopped working until an appropriate number of judges is secured [

3]. Many countries find their own means of trade protection as they watch over protectionism of the great powers. This has become a concern in several WTO reports [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The US imposed an additional tariff of 10–25% on most of the goods imported from China. China retaliated against the US as much as it could, leaving it in a typical tariff war. The 25% of tariffs imposed by the US, with an average tariff rate of 3%, is meant to block the imports from China. Although negotiations have been settled in some areas recently, the prospect is not optimistic.

No country except the US and China dares to unilaterally impose new tariffs. Obviously, nobody wants to be finger-pointed by violating the WTO rules. However, non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs) are difficult to determine the violation of the WTO, and NTBs are therefore often subject to disputes. The WTO member countries tend to be less cautious in adopting new NTBs since violation can be determined through a dispute settlement process. Now, the Appellate Body, the final judging body of the WTO, cannot operate due to the lack of judges, which will be the reason for the expansion of NTBs from next year.

Global protectionism, consisting of tariffs and NTBs, can seriously damage the world economy and global logistics services. According to UNCTAD [

7], global maritime trade expanded at a slower pace of 2.7% and 2.8% in 2018 and 2019 respectively, down from 4.1% in 2017, but it is expected to grow by 3.4% between 2019–2024. However, UNCTAD [

7] seems to be optimistic, assuming that the current WTO system would regulate global trade, although it considers several downside risks in trade tensions and protectionism, and the Brexit (UK’s withdrawal from the EU). It does not take into account the combined effects of high tariffs and NTBs on global port cargo-handling business and containerized global port throughput. The G2 accounts for 40.0% of the global GDP and 22.6% of the world trade, and these two are the core countries of the global value chain (GVC). The impact of the tariff war on international trade and logistics demand can be immense. Considering tariffs and NTBs at the same time, the adverse effects will be magnified.

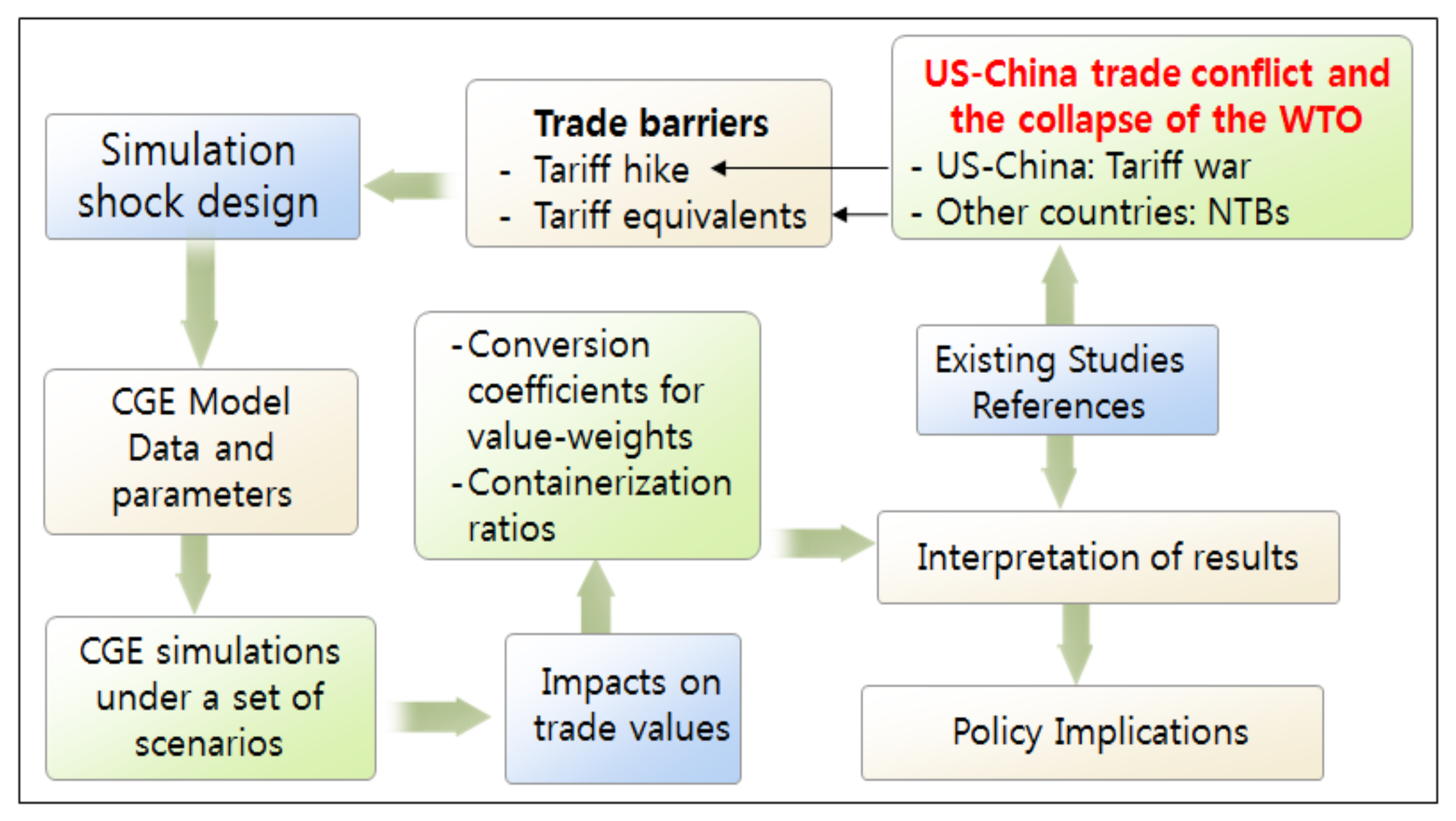

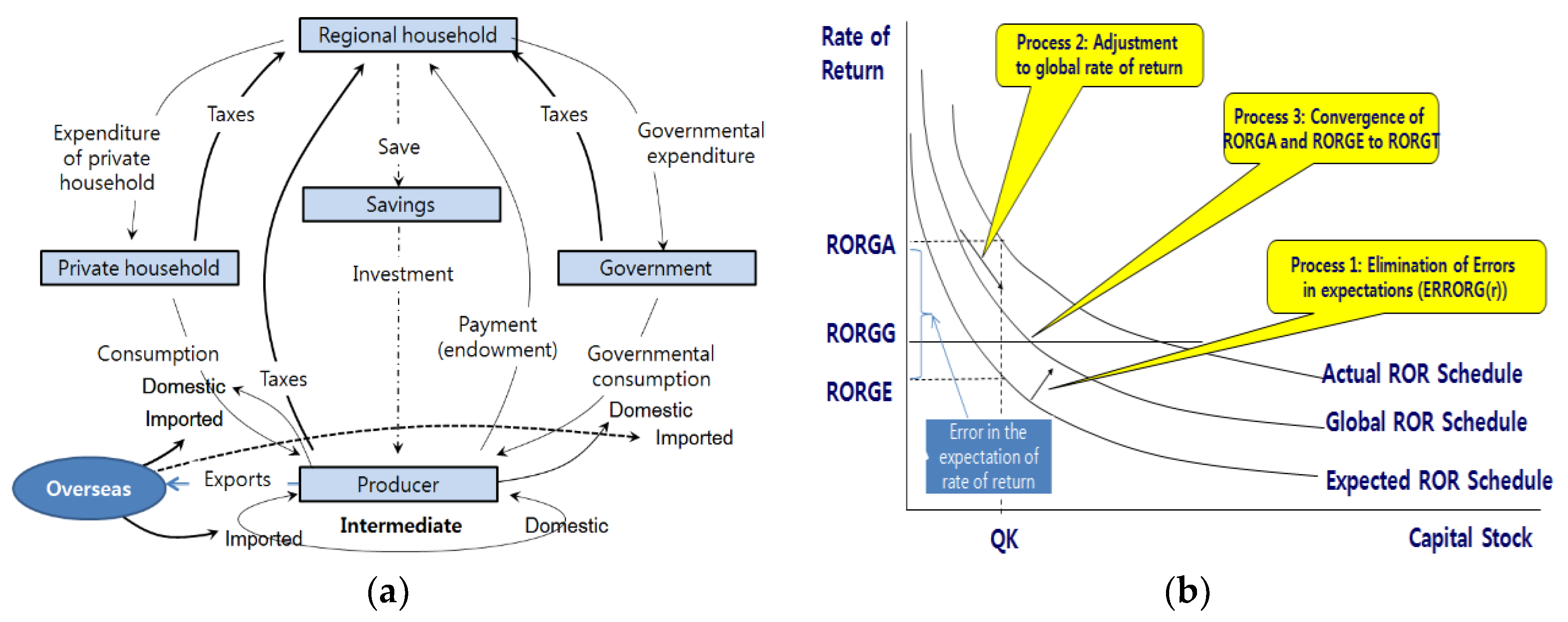

This paper tries to consider that the US-China conflict and the weakened WTO function may lead to installation of new NTBs in other countries and suggests that the combination of tariffs and NTBs can severely reduce the volume of international trade and the demand for maritime logistics services. This paper differs from previous studies in several aspects. Although the world trade system is fundamentally shaken, previous studies mostly scrutinize specific issues and do not analyze the impact on the demand for international shipping services. Around 80% of current global trade comes from the GVC which consists of China and the United States as the key pillars. If the WTO collapses and tariffs and NTBs increase around the world, trade will shrink significantly. In this regard, a question can be raised whether the current international shipping logistics system can be sustained or not. This study aims to estimate the impact of global protectionism on global shipping and logistics, in order to examine whether the industry will be sustainable or not. In this paper, we use various quantitative techniques to estimate the impact of global protectionism from the perspective of trade and logistics services, using a dynamic computational general equilibrium (CGE) model and trade-cargo-container conversion methodology. Based on the simulation results, the paper seeks to draw policy implications.

2. Literature Review on Trade Conflict, NTBs and Logistics

The world has experienced trade and economic growth as a result of trade liberalization under the multilateral trade system of the WTO, but now protectionist trade policies are spreading around the world. Thus, the world trade has been reduced by heightened trade tensions [

8]. WTO [

3,

4,

5] and CGTN [

9] discuss the risk of the WTO, and Mr. Azevêdo, Director-General of the WTO, states “A well-functioning, impartial and binding dispute settlement system is a core pillar of the WTO system.” Ms. Georgieva [

10], IMF Managing Director, confirms that “unfortunately, this time growth is decelerating” due to protectionism. The prolonged period of trade conflict will cause a periodic slowdown of the world economy [

4,

11].

Johnson [

12] performed the modern economic analysis of trade conflict, based on a two-person non-cooperative game in order to select their optimal tariffs considering the partner’s retaliatory tariffs. Tariff wars were analyzed with various approaches by Kennan and Riezman [

13], Eggert and Haufler [

14] and Syropoulos [

15]. Kennan and Riezman [

13] and Syropoulos [

15] tried to identify the significance of economic size in trade models, that consider the terms of trade. Baldwin [

16] and Grossman and Helpman [

17] tried to theorize domestic politics in forming a protective trade policy. Breuss [

18] analyzed the effects of retaliatory tariffs, showing more efficient and accessible instruments than a tariff war.

Based on the relationship between tariffs and the terms of trade, Zissimos [

19] showed the importance of multilateral trade liberalization and region-wide free trade agreements (FTAs). Ossa [

20] developed a quantitative evaluation methodology of trade conflict, estimating Nash-equilibrium tariffs of 56.6% for the US and 62.9% for China, assuming the two-country model and optimal retaliation strategy. A similar approach was performed in Nicita et al. [

21], of which they re-estimated Nash tariffs, drawing that trade conflict would increase the world’s average tariffs by 32%.

Analyzing traditional trade theory and the global trade model, a tariff war and protection trade policy cause economic losses not only in the dispute parties, but also in the world economy. However, strategic approaches by Zissimos [

19], Ossa [

20], and Kee and Nicita [

22], and Nicita et al. [

21] demonstrate the optimal tariffs for large economies in the context of strategic response and long-term gains. It could be one of the backgrounds for the US to enter into a tariff war with China.

A close relationship between logistic efficiency improvements and export performance can be found in substantial literature, including Hummels [

23], Limao and Venables [

24], Wei and Yi [

25], Redding and Venables [

26], Wilson et al. [

27], Anderson and Banomyong [

28], Tongzon [

29], Tongzon and Cheong [

30], Cheong and Suthiwartnarueput [

31], Arvis et al. [

32], and others. These existing studies analyzed the ripple impact of the reduction of logistics costs due to technical and institutional improvements, while this paper analyzes the adverse effects when the trade cost increases due to the increase in tariffs and the expansion of NTBs. CIF-based import costs include trade-related costs such as freight, tariffs and insurance, as well as commodity prices, but the additional costs to overcome NTBs must also be included in the total cost of trade.

Existing research on NTBs is abundant. Examples are Carrère and De Melo [

33], Beghin et al. [

34], Ghodsi and Stehrer [

35] and McCallum and Lincoln [

36]. Many literatures, such as Kee et al. [

37], Disdier and Marette [

38] and Khouilid and Echaoui [

39], used the gravity model in order to estimate the effect of protectionist trade policies on international trade. Researches such as Arkolakis [

40], Hummels and Klenow [

41], and Steingress [

42] approached the NTBs as an additional entry cost to international trade.

The global logistics industry is very concerned about the current international situation and the deterioration of the international trade environment. They expect the US-China trade conflict would distort the supply chain and shrink international trade and logistics demand. This can be found in various sources such as The Financial Times [

43], Supply Chain Digital [

44], Inbound Logistics [

45], Supply Chain Brain [

46], The Asian Banker [

47], Forbes [

48], DHL [

49], Supply Chain Quarterly [

50], and Logistics Management [

51,

52]. They see a serious shock to the recovering global logistics market. According to Supply Chain Digital [

44], CEOs of the world’s major logistics companies believe that trade conflicts affect the global economy as a whole and will cause a severe recession for logistics industries. Forbes [

48] argues that the US’ policy of “decoupling” scrambles the GVC and freezes investment minds. The ‘geopolitical bridges’ between the G2, which have been built over the past 40 years, will burn down. Logistics Management [

52] predicts that Trump’s China policy will also cause significant losses to the US logistics industry, citing that in October 2019, inquiries about ships in the Port of Los Angeles decreased by 25% year-on-year and cargo volume decreased by 19.1%. These studies are merely descriptive assessments and do not quantitatively estimate the impact of global protectionism. Moreover, no literature mentions the increase in NTBs due to the collapse of the WTO.

Regarding the costs of the US-China trade conflict, Ciuriak and Xiao [

53] estimated a 0.062~0.07% decline of global GDP, and Abiad et al. [

54] found 0.2%~1.0% GDP losses for the G2 countries. Carvalho et al. [

55] predicted the welfare losses of 39–43 billion dollars to China and 19–24 billion dollars to the US. Global GDP and trade volume were to be reduced by 1.96% and 17%, respectively, according to Bekkers and Teh [

56]. Trade conflict is hurting China more, but supply chain disruption causes the US to lose its GDP [

57,

58,

59], and the US exports to China up to 71% [

60].

Most of the existing descriptive studies analyze specific issues related to the US-China trade friction, and studies using quantitative models mainly estimate the impact of the protectionist trade measures employed by the US and China on global economic growth or trade losses. Additional tariffs are reflected in the estimate, but do not consider the possibility of the collapse of the WTO and any related risks the global economy faces today. Moreover, quantitative analysis of this on global logistics demand is difficult to find. There is no research that the collapse of the WTO could lead to a new wave of protectionism with NTBs. In this situation, a question can be whether the global trade and logistics industry will be sustainable or not. There arise concerns that the world economy may face a systemic crisis beyond the recession. Furthermore, no debate has taken into account the impact of the combined action of the US–China trade conflict between the G2 and the protectionism of other countries on global trade and logistics. The global logistics industry is also unaware that the suspension of the Appellate Body will have a decisive impact on the international trade system itself under the WTO. This paper focuses on the impact of protectionism on the global logistics industry including fundamental changes in the international trade environment that are not currently drawing enough attention.

4. Simulation Scenarios and Result Interpretation

The last section presented a CGE model for estimating the impact of these trade barriers on world trade and analyzed what forms of global protectionism would appear and the conversion coefficients from trade volume to TEUs. This section sets up the scenarios of quantitative analysis and present the estimation result, using the methodology in

Section 3.

4.1. Tariff War Between China and the US

In December 2019, the US and China agreed on a “phase I out of phase IV’’ (as President Trump claims) 17 months after the US imposed high tariffs on China in July 2018. The agreement is a “small deal," corresponding to only a few of the controversial issues between the two parties. Although the expansion of the G2 trade conflict was avoided, it is not optimistic that the G2 countries will establish a sound trade relationship in the near future. With the idea of ‘decoupling’ between the US and China, the US is “burning down the geopolitical bridges that were built over the past four decades between Washington and Beijing [

48].”

The U.S. charges an additional 25% of tariffs on the Chinese exports worth of

$250 billion and 15% on

$115 billion dollars, while China imposes a 5–25% tariff on the US exports worth of

$110 billion, as of November 2019, as summarized in

Table 4. As the negotiations were sluggish in mid-2019, President Trump threatened to raise tariffs against China. In the early days of the tariff war, China imposed retaliatory tariffs at the same level as the United States, but abandoned its direct confrontation to the US’s huge tariff imposition and proposed to negotiate with the US. The key to Phase I negotiations is as follows. Instead of raising additional tariffs (15% to

$110.5 billion to 30%) by the US, China promised to import US agricultural products worth of

$40–50 billion with some measures about intellectual property rights, financial service market, exchange rate transparency, and others.

Many issues such as forced technology transfers, subsidies by the Chinese government, and state-owned enterprise reform, that will be covered in the second phase of negotiations, are not easily concluded. These are directly related to the structural reform of the Chinese economy. Phase III negotiations could be China’s mechanism for implementing the details of the agreements. The first phase of negotiations is only an outpost, and the second and third stages of negotiations are the main game. The US’ sanction against Huawei, a Chinese tech giant, is deeply linked with its goal to disturb China’s technological hegemony. The US is referring to Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang Uyghur in intentionally irritating the “One China” policy in order to pressure China, which may make the US-China relationship more tangible in the future. The US could also seek a new multilateral trading system to replace the current WTO, pushing for global solidarity to contain China’s unfair trade. As Zeihan [

67] analyzes, the US is either out of the WTO or excludes China from international trade.

The US-China will approach these issues in the context of hegemonic competition and may lead to uncompromising disputes. It will be difficult to reach a second phase agreement, and in the process, the US may issue a new tariff card. The first stage agreement should not be overestimated, and the possibility of a tariff war still exists.

As of November 2019, an additional tariff of 15–25% is imposed on US $366.5 billion, covering 72.13% of the US’ imports from China, and 49.41% of those are required to pay additional 25% tariffs. In 2018, China’s imports from the US were $122.3 billion, with 89.43% of the total imports being levied at 5–25%. This reduced US imports from China by more than 10%, and China’s import from the US by about 20%.

However, the impact of the increase in tariffs was not fully reflected in trade this year, as companies rush trade before tariffs, making the Chinese logistics companies to enjoy an unexpected boom this year. In the future, however, the increased tariff rates will put a heavy burden on trade. High tariffs between the US and China have worked against global growth, “both via the direct effects on trade flows, supply chains and import costs, and via the wider indirect effects on business sentiment, uncertainty, and investment around the world [

64] (p.32).”

4.2. Paralysis of the Appellate Body and NTBs by Other Countries

The impact of the US-China trade friction is not limited to bilateral relations. The US believes that the current WTO rules do not properly regulate China in many aspects such as protecting intellectual property rights and regulating subsidy. Although there are a number of reasons for this, the US decided to make the Appellate Body come to a halt in order to put China in check. The US’ approach to deactivate the WTO is to prevent the appointment of a new judge. New member of the Appellate Body cannot be appointed with the agreement by all member countries.

There is only one member of the Appellate Body after 11 December 2019. Since the Appellate committee cannot be formed with one member, the WTO completely lost its ability to resolve disputes among its members [

9,

61]. This situation extends beyond dispute resolution and affects other member countries in the compliance with the WTO rules since the Appellate Body cannot determine the violation of the WTO rules. This is a part of the reasons why the fact that NTBs have risen to the highest level ever in 2019, as analyzed by the WTO, which reports the highest level of trade restrictions by WTO members this year. “The trade coverage of import-restrictive measures implemented by members was estimated at USD 747 billion. This is the highest trade coverage recorded since October 2012 [

4].”

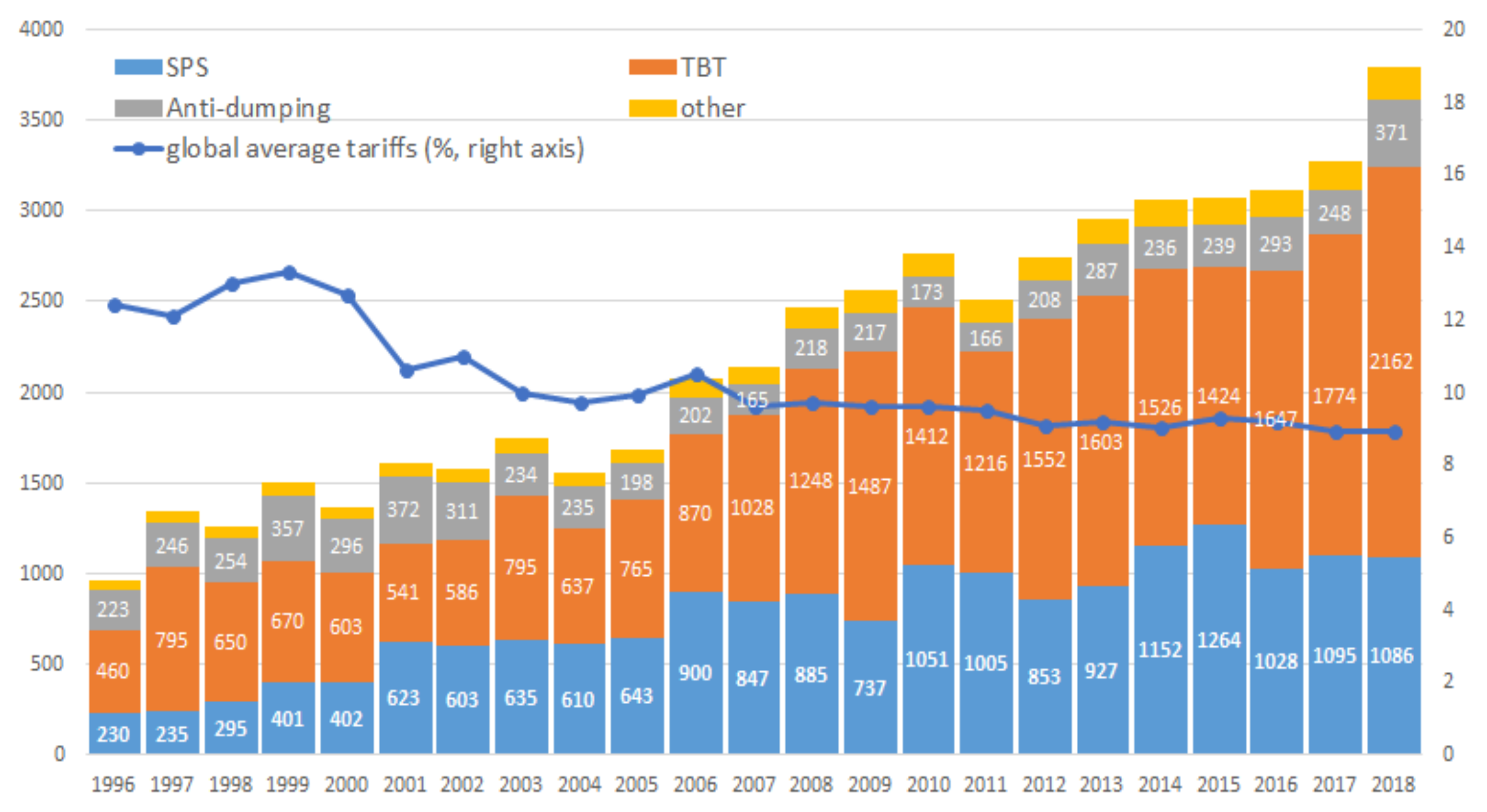

Tariff barriers have been steadily falling due to trade liberalization under the multilateral trading system after World War II, while NTBs have recently increased rapidly. In addition, most of the NTBs are Technical Barrier to Trade (TBT) and Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (SPS) measures, and the proportion of TBT and SPS are increasing. The average world tariff rate is 8.9% in 2017, falling from 13.34% in 1999. Nevertheless, the world has seen a reversed trend in the NTBs since mid-2018. Especially the escalation of bilateral tariffs between China and the US raised the average global tariff rates (not reflected in

Figure 4).

Even if the WTO became ineffective, as only a few countries except the US and China would impose additional tariffs, since this can lead to trade retaliation by the other country. The protectionist trade policy using NTBs tends to have a gray measure, which is less repulsive to counterparts than tariffs. In addition, it is expected that many countries will use it as a means of a protectionist trade policy because it is possible to tailor differentiated measures aimed at specific countries and companies, and it is easy to establish trade barriers without the recognition of other countries due to changes in domestic institutions and practices [

68]. Despite the fact that the WTO regulates the adoption of unfair TBT and SPS, the rapid increase of these in recent years (

Figure 4) suggests that trade barriers by TBT and SPS will increase more rapidly if the WTO’s monitoring of NTBs is weakened.

4.3. Simulation Scenarios

As discussed in Chapter 2, global protectionism consists of the US-China trade conflict and the proliferation of NTBs by the rest of the world. It is difficult to predict future US-China relations under the hegemonic struggle and the US’ decoupling strategy. Although suspended by negotiations, in 2019, the US pushed for a 30% surcharge on China. 15% and 25% are imposed on many items now. As a baseline scenario, we assume that the US set a 20% surcharge on all items imported from China. An optimistic scenario can be an addition of a 10% tariff, while a pessimistic scenario is that of 30% (Nicita, Olarreaga and Silva [

21] predicted that US-China trade war would increase average tariffs by 32%). Considering such multifaceted measures against China, including heavy sanctions against the Chinese firms such as Huawei, investment regulations, and exchange rate transparency, are going on or under planning, the scenarios are set to capture these effects as tariff barriers. Despite the disadvantaged conflict structure compared to the US, it is assumed that China corresponds to the US trade sanctions.

It is very difficult to set NTBs scenarios for the rest of the world. This is because it has to be converted to tariff equivalents (TEs) rather than non-tariff barriers themselves. According to Cadot, Gourdon and Tongeren [

69], which estimated the trade effects of NTB measures in more than 80 countries using the OECD METRO model, the TEs of NTBs, taking into account frequency, was the highest at 28.7% in processed foods, followed with 26.8% in wood and furniture, 22.3% in motor vehicles. The industries with relatively low barriers are 8.3% for shoes, 7.7% for paper, and 6.4% for metal products.

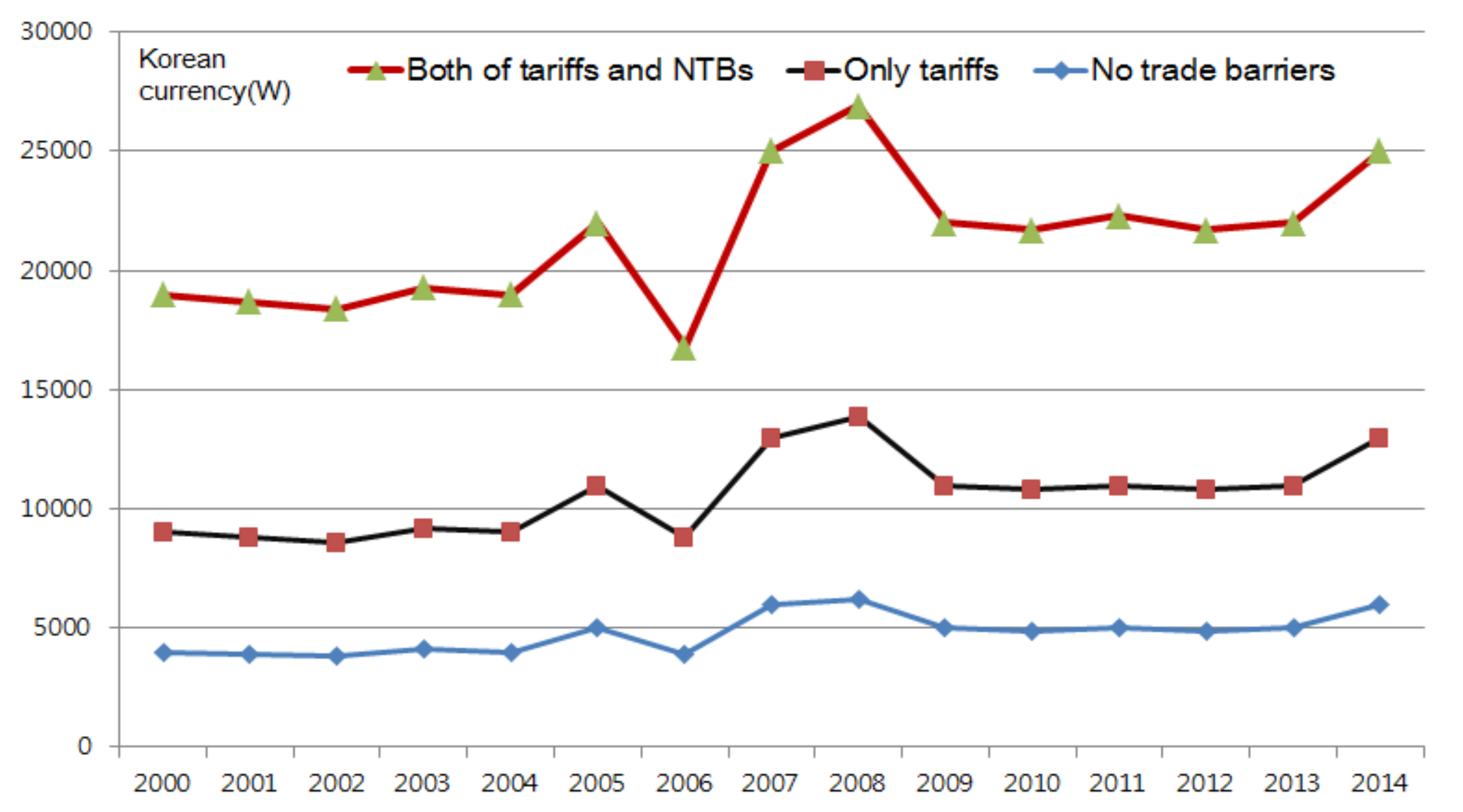

A study analyzing the effects of Korea’s non-tariff measures on imported beef shows that non-tariff barriers were as much as the prices of imported beef between 2000 and 2014, when a high level of non-tariff measures was applied (

Figure 5). In response to Korea’s SPS action, Canada filed a dispute case in the WTO (dispute case: DS391), and Korea withdrew its measure in response to the claim from the exporting country. This can be regarded as an exemplary case, demonstrating the result of a well-functioning dispute settlement system in the WTO.

TEs can be over 100% depending on the measures as seen in the case of Korea, but the TEs in Cadot, et al. [

69] were taken for this paper. It may be controversial, but for the sake of convenience, we will set TEs 15% as the baseline scenario and 10% and 15% as alternative scenarios. The tariff and NTBs scenarios are summarized in

Table 5.

As suggested above, NTBs are mainly TBT- and SPS-related measures, and they are gray in nature, making it difficult to quantify the effects of NTBs. In particular, Carrère, Céline and De Melo [

33] point out that NTBs are the most difficult to model because of the grey characteristics. According to Crivelli and Groeschl [

70], SPS itself provides high flexibility for importing countries, so many countries use it as the most effective means of protecting domestic producers. These obstacles make it more difficult to calculate the TEs of NTBs in this study. Therefore, a set of scenarios by integrating the results of the existing research was established for simulations.

4.4. Simulation Results

Table 6 summarizes the impact on international trade, global cargo and container logistics under the scenarios set out in this paper. The impact on the global logistics industry could be significant. In Scenario 1, international trade would shrink by

$7.2 trillion, and if Scenario 3 is realized,

$12.8 trillion of trade is anticipated to disappear. Considering that the world’s total trade volume in 2018 is

$39.3 trillion [

5], 32.5% will be reduced under Scenario 3, and the impact on the international logistics industry can be enormous.

Global cargo losses are expected to be between 6.2 and 10.8 trillion tons by weight, and port cargo is expected to decrease by 3.95 to 6.9 trillion tons, depending on the scenario. Under Scenario 2, which is the baseline scenario, the reduction in containerized cargo is expected to be 2.97 trillion tons, while the non-container cargo is expected to be reduced by 2.56 trillion tons. The reduced weight of containerized cargo in terms of TEUs translates into 153–267 million TEUs across the scenarios. Considering that the annual container throughput of Shanghai Port, the world’s largest container port in 2018, is 42 million TEUs. If Scenario 3 is realized, the impact on the global logistics industry will have the same impact as the lost volume that is six times larger than that of Shanghai. This must be a huge shock.

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the contents of

Table 6 by each scenario and industry. It is suggested that the industry with the most trade and logistics losses throughout the scenarios will be petrochemicals and chemicals. Following petrochemicals, electrical goods could be hit hard. The steel and transportation equipment industries are expected to have moderate impact and the impact on the rest of the industry to be relatively modest.

Looking at the estimates under Scenario 1, more than a half of the total trade and volume losses are in the petrochemical industry, but the losses in the textile and apparel industry are likely to be small, less than 1% of the total. Non-container cargo losses in the petrochemical industry are expected to decrease by 1.06 trillion tons and to lose 71 million TEUs of cargo handling opportunities. Container cargo losses in steel and agriculture are also expected to exceed 20 million TEUs.

If scenarios change to 2 and 3, the estimates will increase more than in Scenario 1, suggesting that the adverse effects of global trade protection will deepen. Still, the proportion of petrochemicals in non-container and container cargo losses is overwhelmingly high. The industry with the weakest container cargo loss across all the scenarios is machinery, with container cargo losses between 1.59 and 2.8 million TEUs.

5. Conclusions

Various risks and uncertainties are strengthening the downside of the global economy [

71]. The industry of financial and international trade services is cheering on the fragmentary news of positive discussions between the US and China, probably because of the anticipation of avoiding the worst situation. However, the US-China conflict cannot be resolved within 1–2 years (Mr. Jack Ma of Alibaba said that “the US-China relationship will be in some turbulence for the next 20 years” in his interview with Bloomberg 14 November 2019). The US sees China in the context of a security-trade nexus, while China is trying to resolve it in the trade landscape.

This paper estimates international port cargo losses from the current global protectionism to range from 3.95 to 6.9 billion tons, depending on the scenarios. Considering the 2018 global maritime cargo was 11 billion tons according to UNCTAD [

7], global logistics demand is expected to decrease by half if Scenario 3 becomes a reality. This must be a huge shock to logistics industries. This paper underlines that if the world trade order is not normalized, a catastrophe may occur in the world economy as well as the logistics industry.

Academics and the industry have not fully considered the adverse effects of the shutdown of the WTO Appellate Body. The WTO itself will remain, and the trade environment will gradually deteriorate due to invisible non-tariff barriers, but the cumulative effect can be enormous. As reviewed in Chapter 2, no prior quantitative research on the impact of global protectionism on maritime logistics sector can be found.

Reasonable dispute settlement procedures are of paramount importance in the WTO’s function, ensuring that each member country complies with the WTO trade rules and prevents trade conflicts from escalating into a war such as World War I and World War II. This is why the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference (Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan in June 2020) will be critical in restoring the global trade order. The international community should re-establish the status of the WTO by agreeing to a well-functioning dispute settlement system and discontinuing its protectionist policies.

Overall, this paper suggests that the global logistics industry may have a shocking impact. In this regard, the limitations in this estimation can also be pointed out. First, the question of the adequacy of the scenario setting can be raised. A partially relaxed level of global trade protection can be established, but the international trade environment should never be taken lightly when the WTO system becomes incapacitated. Second, the refinement of the conversion coefficient by region will increase the accuracy of the estimates. Since it is difficult to secure data and is a task that requires a lot of effort, it should be balanced with importance. Third, the petrochemical industry accounts for more than half of the overall impact in

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9. There are many different types of petrochemicals. While dry products can be transported in containerized cargo, a large portion of liquid petrochemicals are transported in tank ships. These characteristics of the petrochemical industry need to be reflected more precisely in research. While estimates may change as new conversion factors become available, the conclusion that a serious impact is expected for the global logistics industry remains.