Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Organizational Identification, Perceived External Prestige, and Turnover Intention

2.2. The Effect of Cultural Values on Turnover Intentions

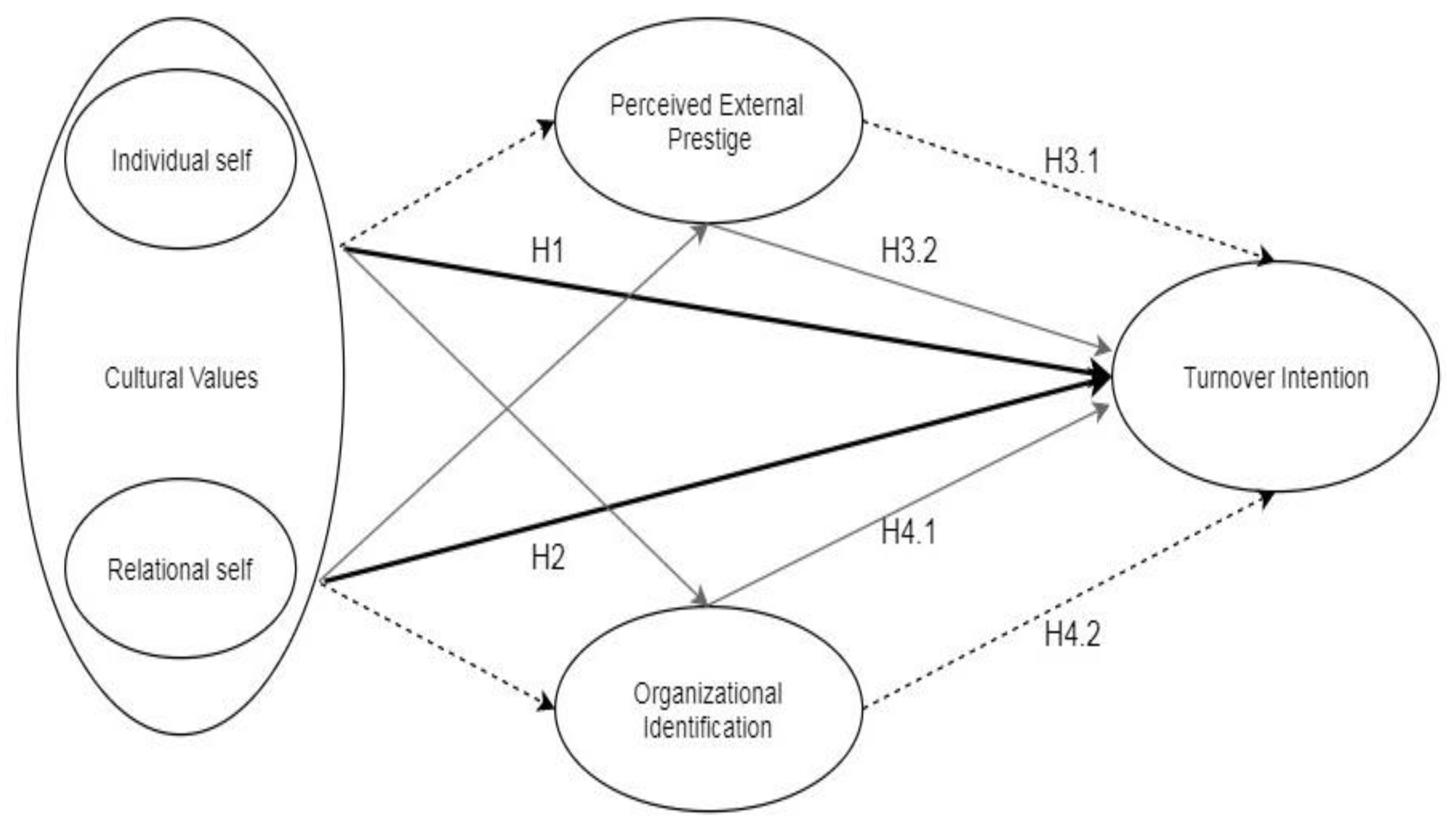

2.3. The Mediating Role of OID and PEP

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Measurement Instrument

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.2. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, M.; Fried, D.D.; Griffeth, R.W. A review of job embeddedness: Conceptual, measurement issues, and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, B.C.; Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W.; Eberly, M.B. 5 Turnover and Retention Research: A Glance at the Past, a Closer Review of the Present, and a Venture into the Future. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 231–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Podvezko, A.; Bilan, Y. Feasibility of stakeholder participation in organizations of common interest for agricultural policymaking. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 18, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljegren, M.; Ekberg, K. The Associations between perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional organizational justice, self-rated health and burnout. Work 2009, 33, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Ross, A.D.; Sertyeşilışık, B. Testing the unfolding model of voluntary turnover construction professionals. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryer, C.; Leighton, C.; Firns, I.; Travaglione, A. Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Allen, D.G.; Froese, F. Organizational embeddedness, turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover: The moderating effects of employee demographic characteristics and value orientations. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construal’s. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; McQuaid, R.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, I. The Impact of Job Retention on Continuous Growth of Engineering and Informational Technology SMEs in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeenk, S.G.A.; Eisinga, R.N.; Teelken, J.C.; Doorewaard, J.A.C.M. The effects of HRM practices and antecedents on organizational commitment among university employees. IJHRM 2006, 17, 2035–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. The psychology of lateness, absenteeism, and turnover. In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology; Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 232–252. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.T.; Wan, C.S.; Fu, Y.J. Qualitative Examination of Employee Turnover and Retention Strategies in International Tourist Hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilau, A.; Ajagbe, A.M.; Sholanke, A.B.; Sani, T.A. Impact of employee turnover in small and medium construction firms: A literature review. IJERT 2015, 4, 977–984. [Google Scholar]

- Cordelia, H.S.; Florence, Y.Y.L. Strategies for reducing employee turnover and increasing retention rates of quantity surveyors. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Ozorhon, B. Analysis of construction innovation process at project level. J. Manag. Eng. 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A Systematic Review of the Corporate Reputation Literature: Definition, Measurement, and Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, Y.Y.; Kiazad, K.; Zhou, L.; Capezio, A.; Li, M.; Restubog, S.L.D. Investigating employee turnover in the construction industry: A psychological contract perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Picken, D. Exploring turnover intention of construction managers in China. J. Constr. Res. 2006, 7, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Tang, C.; Day, J.; Adler, H. Supervisor support and turnover in hotels: Does subjective well-being mediate the relationship? IJCHM 2019, 31, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ran, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yao, H.; Zhu, S.; Tan, X. Moderating role of job satisfaction on turnover intention and burnout among workers in primary care institutions: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, S.; Godkin, L. Banking Employees’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility, Value-Fit Commitment, and Turnover Intentions: Ethics as Social Glue and Attachment. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2017, 29, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- René, M.; Cynthia, K.R.; Robin, L.W. Psychological contract and turnover intention in the information technology profession. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2019, 36, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield, K.D. The Role of Sense making and Organizational Identification in Employee Engagement for Sustainability. Organ. Manag. J. 2019, 16, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepian, J.L.; Jones, G.E. Gender and Corporate Sustainability: On Values, Vision, and Voice. Organ. Manag. J. 2013, 10, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.; Lee, T.; Shaw, J.; Hausknecht, J. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackers, P. Rethinking the employment relationship: A neo-pluralist critique of British industrial relations orthodoxy. IJHRM 2014, 25, 2608–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.E.; Cameron, J.E. Multiple dimensions of organizational identification and commitment as predictors of turnover intentions and psychological well-being. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2005, 37, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanika-Murray, M.; Duncan, N.; Pontes, H.; Griffiths, M. Organizational identification, work engagement, and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Taha, V.; Sirková, M.; Ferencová, M. The impact of organizational culture on creativity and innovation. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 14, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Huh, S.; Cho, S.; Auh, E. Turnover and retention in nonprofit employment: The Korean college graduates’ experience. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Freund, A. Linking perceived external prestige and intentions to leave the organization: The mediating role of job satisfaction and affective commitment. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2009, 35, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y.; Bardakoglu, Ö. The impacts of perceived organizational prestige and organization identification on turnover intention: The mediating effect of psychological empowerment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1510–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, J.; Pruyn, A.; De Jong, M.; Joustra, I. Multiple OID levels and the impact of PEP and communication climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepanjana, V. Impact of self-concept on turnover intention: An empirical study. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2014, 4, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, J.; Staw, B. Individualism-collectivism and group creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 100, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- İmamoglu, E.O.; Kuller, R.; Imamoglu, V.; Miller, M. The social psychological worlds of Swedes and Turks in and around retirement. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1993, 24, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagitçibasi, C. Individualism and collectivism. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Vol. 3. Social Behavior and Applications (1–49); Berry, J.W., Segall, M.H., Kagitcibasi, C., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Antonius, R. Interpreting Quantitative Data with SPSS; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- İmamoğlu, E.O. Individuation and relatedness: Not opposing but distinct and complementary. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2003, 129, 367–402. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 517–554. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B. Loyal from one day: Biodata organizational identification, and turnover among newcomers. Pers. Psychol. 1992, 48, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J.; Tuttle, J. Employee turnover: A meta-analysis and review with implication for research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; William, C.B.; Barry, J.B.; Rolph, E.A. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.C. Statistical Methods for Psychology, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, P.R.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In Sociological Methodology; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T.D.; Bovaird, J.A.; Widaman, K.F. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Struct. Equ. Model. 2006, 13, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, T.R.; Bresnahan, M.J.; Park, H.S.; Lapinski, M.K.; Wittenbaum, G.M.; Shearman, S.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Chung, D.; Ohashi, R. Self-construal scales lack validity. Hum. Commun. Res. 2003, 29, 210–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics of Respondents | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 168 | 38.1 |

| Male | 273 | 61.9 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 255 | 58.0 |

| 30–39 | 117 | 27.0 | |

| 40–49 | 53 | 12.0 | |

| Above 50 | 16 | 3.0 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s degree | 325 | 73.7 |

| Master’s degree | 107 | 24.3 | |

| PhD | 9 | 2.0 | |

| Organizational Tenure | Less than 1 year | 118 | 26.8 |

| 1–5 | 201 | 45.6 | |

| 6–10 | 68 | 15.4 | |

| 11–15 | 30 | 6.8 | |

| Above 16 | 24 | 5.4 | |

| Job title | Architect | 236 | 53.6 |

| Civil Engineer | 205 | 46.4 | |

| Model No. | Model | ∆χ² | df | ∆χ²/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Partial Mediation Model | 472.151 | 4.11 | 1.943 | 0.046 | 0.914 | 0.977 | Acceptable |

| 2 | Partial Mediation Model | 447.389 | 4.11 | 1.841 | 0.044 | 0.918 | 0.982 | Acceptable |

| 3 | Full Mediation Model | 645.223 | 3.16 | 2.042 | 0.049 | 0.876 | 0.971 | Acceptable |

| 4 | Full Mediation Model | 651.175 | 3.16 | 2.061 | 0.049 | 0.989 | 0.973 | Acceptable |

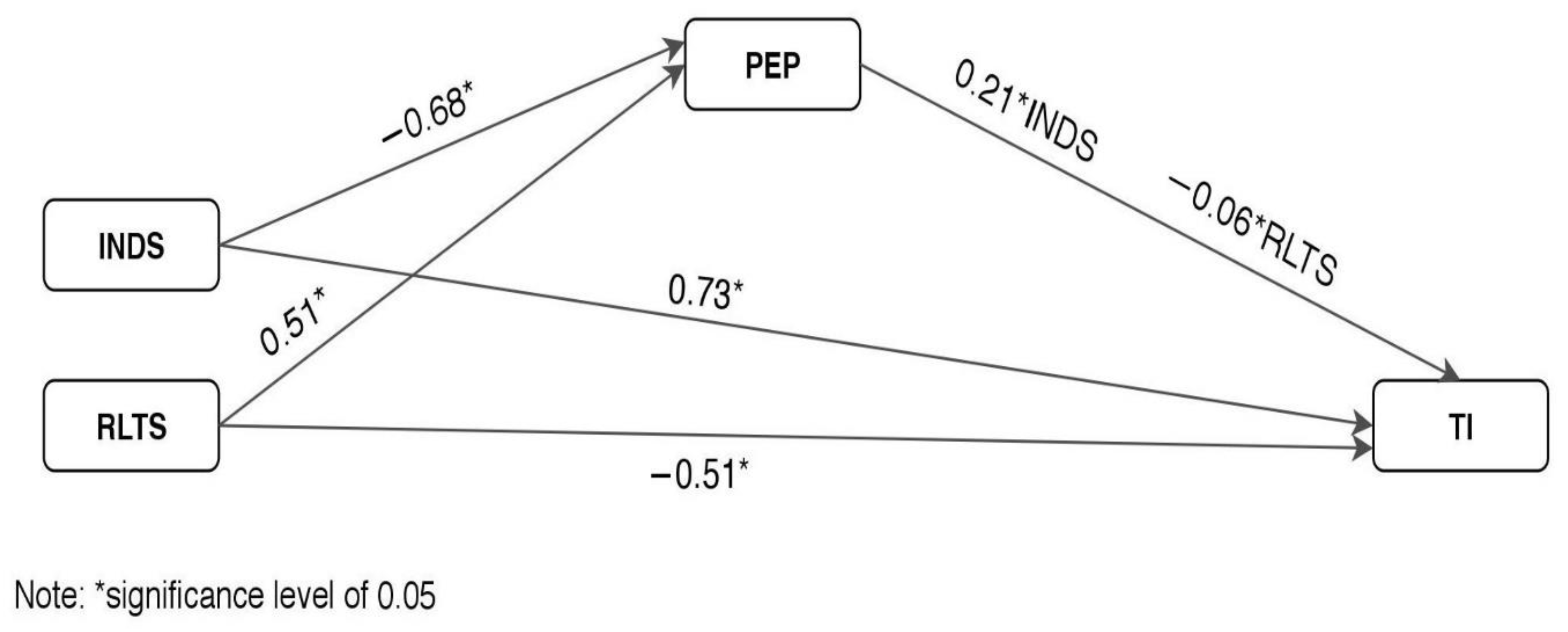

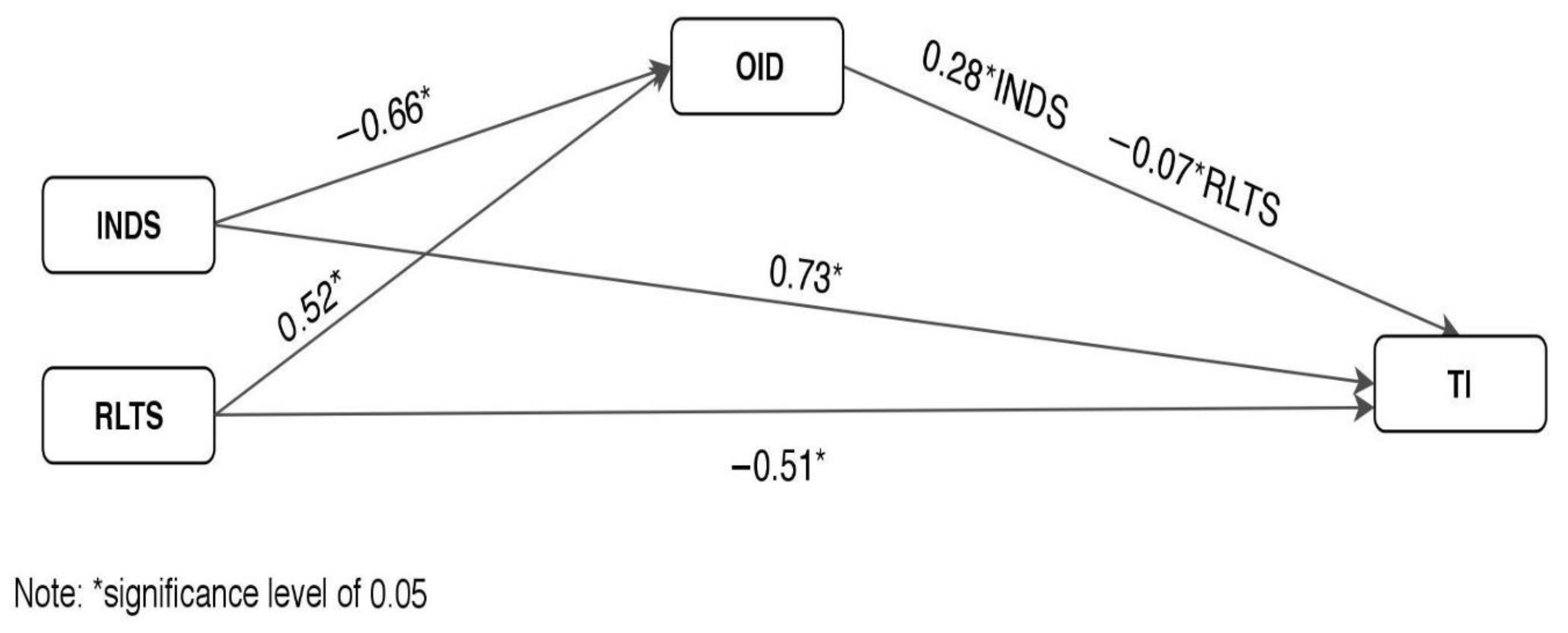

| Standardized Path Coefficients Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | Partial mediation | Full mediation | |||||

| Individual self | → | Turnover Intention | 0.73 * | ||||

| Relational self | → | Turnover Intention | −0.51 * | ||||

| Individual self | → | PEP | → | TOI | 0.68 * | 0.21 * | |

| Individual self | → | IOD | → | TOI | 0.73 * | 0.28 * | |

| Relational self | → | PEP | → | TOI | −0.52 * | −0.06 * | |

| Relational self | → | IOD | → | TOI | −0.51 * | −0.07 * | |

| Hypothesis | Explanation | Analyze | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H 1 | Individual self is positively related to TOI | SEM | Accepted |

| H 2 | Relational self is negatively related to TOI | SEM | Accepted |

| H 3.1 | PEP mediates the relationship among individual self and TOI | SEM | Partially Supported |

| H 3.2 | PEP mediates the relationship among relational self and TOI | SEM | Partially Supported |

| H 4.1 | OID mediates the relationship among relational self and TOI | SEM | Accepted |

| H 4.2 | OID mediates the relationship among individual self and TOI | SEM | Accepted |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uğural, M.N.; Giritli, H.; Urbański, M. Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030954

Uğural MN, Giritli H, Urbański M. Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030954

Chicago/Turabian StyleUğural, Mehmet Nurettin, Heyecan Giritli, and Mariusz Urbański. 2020. "Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030954

APA StyleUğural, M. N., Giritli, H., & Urbański, M. (2020). Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability, 12(3), 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030954