The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and Social Innovation in Academic Spin-Offs

3. Development of the Hypotheses

3.1. Social Context of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

3.2. Institutional Context of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

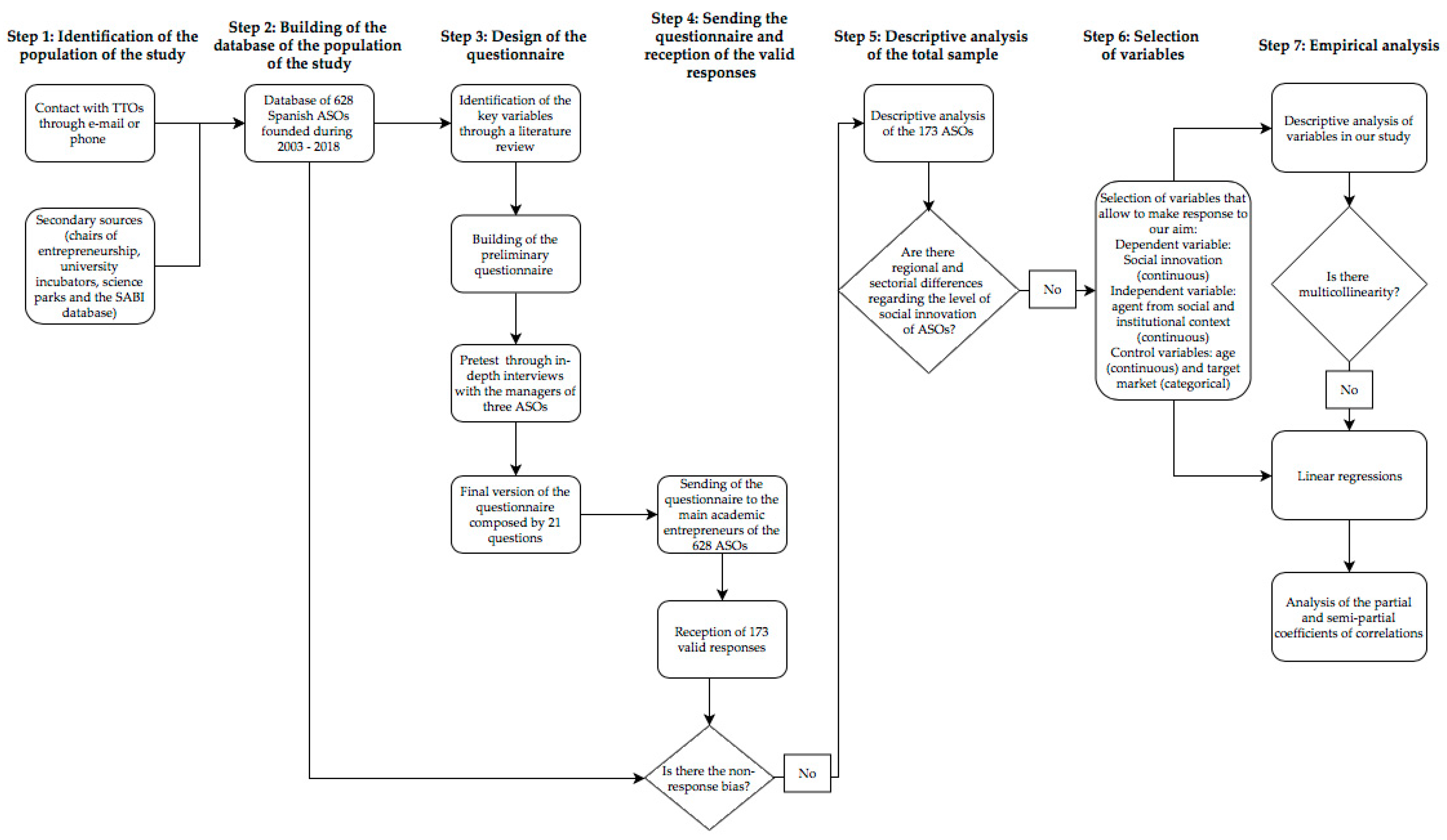

4. Methodological Framework

- Dependent variable: “Social innovation”. In order to measure the social innovation of ASOs, our dependent variable was based on the Regional Social Innovation Index (RESINDEX), which provides a conceptual and empirical model that explores indicators of social innovation at organizational and regional levels [90]. This index is inspired by recent reports of the European Commission [91,92] and has been generated by SINNERGIAK Social Innovation [40]. Specifically, our focus was on the following three dimensions of the index: (i) acquisition of external knowledge; (ii) impact of social innovation; and (iii) social governance. First, in order to measure the acquisition of external knowledge for the development of social innovation, the main academic founder was requested to indicate, on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree), their level of agreement with the following statements: “We have employees or units focused on identifying social demands”; and “We use various sources of information to identify social demands” [42]. Second, we measured the impact of social innovation through the level of agreement of the main academic founder with the following statements, again on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree): “Our innovations contribute to the development of products, processes, and/or services that resolve unsatisfied social demands, thereby improving people’s way of life”; and “Our social innovations have a high degree of internationalization” [82]. Lastly, on the same Likert scale, social governance was reported through the level of agreement of the main academic founder with respect to both the degree of involvement of society in the identification of the social demands, and the degree of sustainability of the social innovation [42].In order to ascertain whether these six items could be grouped to create a single social innovation variable, a principal component analysis was performed. The results of this analysis reported an appropriate level of internal consistency (α = 0.86) and a correct sampling adequacy (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Test = 0.85). The percentage of total variance explained rose to 58.3%. In addition, as Hair et al. [93] recommended, all factor loadings were greater than 0.40, and all communalities exceeded 0.50.

- Independent variables: “Actors from the social and institutional contexts of the entrepreneurial ecosystem”. In order to identify the key actors of the social and institutional contexts of the entrepreneurial ecosystem of ASOs, an extensive literature review was carried out, which revealed that the social context comprises relationships with national and international customers, suppliers, competitors, and VCs. The institutional context is composed of relationships with national and international government institutions, TTOs, incubators, other academics, chairs of entrepreneurs, and research centers [20,94,95]. By focusing on Mitchell [96] and Smith et al. [97], the frequency of contact was employed to measure the interactions of ASOs with each agent. The main academic founders were therefore asked to indicate on a five-point Likert scale (1: fewer than one contact per month; 5: multiple daily contact) the frequency of contact with: (i) national customers, suppliers, and competitors; (ii) international customers, suppliers, and competitors; (iii) national and international VCs; (iv) national and international government institutions; (v) national and international TTOs; and (vi) national and international university institutions.

- Control variables: “age” of the ASO and its “target market”. On the one hand, the age of an ASO was measured by calculating the number of years from the founding of the firm until the year 2018. On the other hand, in order to measure the target market, we asked the main academic founder to indicate the option that best described the market in which the company operated: market niche (small and specific customer group); or dominant market (large market where several companies operate) [98].Table A1 provides a detailed description of the measures used in the study.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Social Innovation (SINNERGIAK Social Innovation, 2013) |

| Please, indicate on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree), your level of agreement with the following statements: |

| We have employees or units focused on identifying social demands |

| We use various sources of information to identify social demands |

| Our innovations contribute to the development of products, processes, and/or services that resolve unsatisfied social demands, thereby improving people’s way of life |

| Our social innovations have a high degree of internationalization |

| The degree of involvement of the society in the identification of the social demands is high |

| The degree of sustainability of the social innovation is high |

| Social context (Mitchell, 1982; Smith et al., 2005; Mosey and Wright, 2007; Franco-Leal et al., 2019) |

| Please, indicate on a five-point Likert scale (1 = fewer than one contact per month; 5 = multiple daily contact) the frequency of contact with the following actors: |

| National customers, suppliers, and competitors |

| International customers, suppliers, and competitors |

| National and international VC firms |

| Institutional context (Mitchell, 1982; Smith et al., 2005; Mosey and Wright, 2007; Franco-Leal et al., 2019) |

| Please, indicate on a five-point Likert scale (1 = fewer than one contact per month; 5 = multiple daily contact) the frequency of contact with the following actors: |

| National and international government institutions |

| National and international TTOs |

| National and international university institutions |

| Age of ASO |

| Please, indicate the year in which the ASO was founded: |

| Target market (Clarysse et al., 2007) |

| Please, indicate the option that best describes the market of the company: |

| Market niche (small and specific customer group) |

| Dominant market (large market where several companies operate) |

References

- Mustar, P.; Renault, M.; Colombo, M.G.; Piva, E.; Fontes, M.; Lockett, A.; Wright, M.; Clarysse, B.; Moray, N. Conceptualising the heterogeneity of research-based spin-offs: A multi-dimensional taxonomy. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustar, P.; Wright, M.; Clarysse, B. University spin-off firms: Lessons from ten years of experience in Europe. Sci. Public Policy 2008, 35, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, V.; Van Der Duin, P. Responsible innovation among academic spin-offs: How responsible practices help developing absorptive capacity. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2015, 15, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, R.; Rasmussen, E.; Siegel, D.; Wiklund, J. Rethinking the Commercialization of Public Science: From Entrepreneurial Outcomes to Societal Impacts. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundström, A.; Zhou, C. Promoting innovation based on social sciences and technologies: The prospect of a social innovation park. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 24, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniccia, P.M.A.; Baiocco, S. Co-Evolution of the University Technology Transfer: Towards a Sustainability-Oriented Industry: Evidence from Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K.; Tiemann, I. Factors influencing university support for sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from explorative case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekula, R.; Shah, A.; Jhamb, J. Universities as Intermediaries: Impact Investing and Social Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 18886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nejabat, R.; Taheri, M.; Scholten, V.; Van Geenhuizen, M. University spin-offs’ steps in commercialization of sustainable energy inventions in northwest Europe. In Cities and Sustainable Technology Transitions: Leadership, Innovation and Adoption; Van Geenhuizen, M., Hobrook, A., Taheri, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hazenberg, R.; Bajwa-Patel, M.; Roy, M.J.; Mazzei, M.; Baglioni, S. A comparative overview of social enterprise ‘ecosystems’ in Scotland and England: An evolutionary perspective. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2016, 26, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbaj, M.; Hadi, K.E.O.E.; Elamrani, J.; Lemtaoui, M. A Study of the Social Entrepreneurship Ecosystem: The Case Of Morocco. J. Dev. Entrep. 2016, 21, 1650021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windrum, P.; Schartinger, D.; Rubalcaba, L.; Gallouj, F.; Toivonen, M. The co-creation of multi-agent social innovations: A bridge between service and social innovation research. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 19, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melane-Lavado, A.; Álvarez-Herranz, A. Different Ways to Access Knowledge for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T. Social Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Complementary or Disjointed Phenomena? SSRN Electron. J. 2017, 44, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.K.; Villari, B.C.; Subramanian, B. Developing Platform Ecosystem for Resource Mobilization: The Case of Social Enterprises in India. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2018, 20, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, B.; Muurlink, O.; Best, T. The political ecology of university-based social entrepreneurship ecosystems. J. Enterp. Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2018, 12, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strat. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A.; Shaw, E.; Lewis, K.V. The collaborative dynamic in social entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvedalen, J.; Boschma, R. A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 88, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Leal, N.; Camelo-Ordaz, C.; Fernandez-Alles, M.; Sousa-Ginel, E. The Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: Actors and Performance in Different Stages of Evolution of Academic Spinoffs. Entrep. Res. J. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M.; Wright, D. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, M.; Romano, M.; Del Giudice, M.; Schillaci, C.E. The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: A measurement framework. J. Technol. Transfer 2018, 43, 640–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, H. The development of an infrastructure for entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Altinay, L. How social capital is leveraged in social innovations under resource constraints? Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1772–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilling, O.R. The entrepreneurial system: On entrepreneurship in the context of a mega-event. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. Playing the field: A new approach to the meaning of social entrepreneurship. Soc. Enter. J. 2006, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A.; Murdock, A. The nature of social innovation. In Social Innovation; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, B. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J.C.; Moss, T.W.; Lumpkin, G.T. Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strat. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.; O’Sullivan, P.; Smith, M.; Esposito, M. Perspectives on the role of business in social innovation. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Gotteland, D.; Haon, C.; Zimmer, J. Making Innovation Last: Sustainable Strategies for Long Term Growth; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The process of social innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phills, J.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, D. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.bibezproxy.uca.es/docview/217166206?pq-origsite=summon (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Roome, N. Innovation, global change and new capitalism: A fuzzy context for business and the environment. Hum. Ecol. Forum 2004, 11, 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey, M.; Zaring, O. Co-delivery of social innovations: Exploring the university’s role in academic engagement with society. Ind. Innov. 2018, 25, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, A.; Dankbaar, B. Does social innovation require social entrepreneurship? Tech. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2014, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Empowering People, Driving Change: Social Innovation in the European Union [Electronic Version] 2011. Available online: http://www.ess-europe.eu/sites/default/files/publications/files/social_innovation_0.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Dro, I.; Therace, A.; Hubert, A. Empowering People, Driving Change: Social Innovation in the European Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Overy, P.; Denyer, D. Innovating for Sustainability: A Systematic Review of the Body of Knowledge. 2012. Available online: http://nbs.net/wp-content/uploads/NBS-Systematic-Review-Innovation.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Sinnergiak Social Innovation. Regional Social Innovation Index. In A Regional Index to Measure Social Innovation; Basque Innovation Agency: Bilbao, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, E.; Ville, S. Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value”. Calif. Mana. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Mulgan, G.; Caulier-Grice, J. How to Innovate: The tools for social innovation. Retriev. April 2008, 28, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemann, I.; Fichter, K.; Geier, J. University support systems for sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from explorative case studies. Int. J. Entrepren. Ven. 2018, 10, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, C. In search of the profit-maximizing actor: Motivations and definitions of success from nascent academic entrepreneurs. J. Technol. Transfer 2011, 36, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Garnsey, E. Policy-driven ecosystems for new vaccine development. Technovation 2014, 34, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiolini, R.; Marra, A.; Baldassarri, C.; Carlei, V. Digital Technologies for Social Innovation: An Empirical Recognition on the New Enablers. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2016, 11, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yu, X.; Cao, L. Co-creation of social innovation: Corporate universities as innovative strategies for Chinese firms to engage with society. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L. What is societal impact of research and how can it be assessed? A literature survey. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Tec. 2013, 64, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulou, F.A.; Koufopoulos, D.N. The Influence of Relational Embeddedness on the Formation and Performance of Social Franchising. J. Mark. Channels 2013, 20, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H. Community-Led Social Venture Creation. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2007, 31, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobele, L.; Pietere, A. Competitiveness of social entrepreneurship in latvia. Reg. Form. Dev. Stud. 2015, 17, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubini, P. The influence of motivations and environment on business start-ups: Some hints for public policies. J. Bus. Ventur. 1989, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T. The Search-Transfer Problem: The Role of Weak Ties in Sharing Knowledge across Organization Subunits. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network Structure and Knowledge Transfer: The Effects of Cohesion and Range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manage. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, T.; Werner, A. How exactly do network relationships pay off? The effects of network size and relationship quality on access to start–up resources. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 501–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E. The Regional Impacts of University Spin-offs: In What Ways do Spin-Offs Contribute to the Region? Forthcoming, Handbook on Universities and Regional Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schillo, R.S. Research-based spin-offs as agents in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. J. Technol. Transfer 2018, 43, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, C.S. A trajectory of early-stage spinoff success: The role of knowledge intermediaries within an entrepreneurial university ecosystem. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, C.S.; Nelson, A.J.; Zayed, S.; O’Connor, A.C. Conceptualizing academic entrepreneurship ecosystems: A review, analysis and extension of the literature. J. Technol. Transfer 2018, 43, 1039–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The New Field of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Studying Entrepreneurial Action Linking “What Is to Be Sustained” With “What Is to Be Developed”. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, R.E.; Medellín, E.; Scanlon, A.P.; Solleiro, J.L. Motivations and obstacles to university industry cooperation (UIC): A Mexican case. R&D Manag. 1994, 24, 017–030. [Google Scholar]

- Lyles, M.A.; Salk, J.E. Knowledge Acquisition from Foreign Parents in International Joint Ventures: An Empirical Examination in the Hungarian Context. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 877–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, F. The university’s unknown knowledge: Tacit knowledge, technology transfer and university spin-offs findings from an empirical study based on the theory of knowledge? J. Technol. Transfer 2013, 38, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, D.; Lumpkin, G.T. Strategic foci in social and commercial entrepreneurship: A comparative analysis. J. Soc. Entrep. 2012, 3, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Murray, G.; Wright, M. Do UK venture capitalists still have a bias against investment in new technology firms? Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1009–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohora, A.; Wright, M.; Lockett, A. Critical junctures in the development of university high-tech spinout companies. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munari, F.; Toschi, L. Do venture capitalists have a bias against investment in academic spin–offs? Evidence from the micro– and nanotechnology sector in the UK. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2011, 20, 397–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Liu, G. Which Iron Cage? Endo-and exoisomorphism in Corporate Venture Capital Programs. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 477–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx, J.; Leonard, R. The Conversion of Social Capital into Community Development: An intervention in Australia’s outback. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozhikin, I.; Macke, J.; Da Costa, L.F. The role of government and key non-state actors in social entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.A.L.; Helms, K. Indigenous Social Entrepreneurship: The Gumatj Clan Enterprise in East Arnhem Land. J. Entrep. 2013, 22, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, J.H.; McCarthy, D. Policy venture capital foundations, government partnerships, and child care programs. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 319–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Gundry, L.K.; Kickul, J.R. The socio-political, economic, and cultural determinants of social entrepreneurship activity an empirical examination. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.L. The world of the social entrepreneur. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2002, 15, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, H.; Gawell, M. Building Social Capital for Social Entrepreneurship. Ann. Public Cooperative Econ. 2012, 83, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.; Lyon, F.; Baldock, R. Playing with Numbers: A Methodological Critique of the Social Enterprise Growth Myth. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K.; Clausen, J. Diffusion Dynamics of Sustainable Innovation-Insights on Diffusion Patterns Based on the Analysis of 100 Sustainable Product and Service Innovations. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 4, 30–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disterheft, A.; Caeiro, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Filho, W.L. Sustainable universities e a study of critical success factors for participatory approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breznitz, S.M.; Clayton, P.A.; Defazio, D.; Isett, K.R. Have you been served? The impact of university entrepreneurial support on start-ups’ network formation. J. Technol. Transfer 2018, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensley, M.D.; Hmieleski, K.M. A comparative study of new venture top management team composition, dynamics and performance between university-based and independent start-ups. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, V.E. The Early Growth of Academic Spin-Offs: Factors Influencing the Early Growth of Dutch Spin-Offs in the Life Sciences, ICT and Consulting. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- COTEC Report. Fundación COTEC para la Innovación. 2018. Available online: http://informecotec.es/media/Informe-Cotec_2018_versi%C3%B3nweb.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Unceta, A.; Castro-Spila, J.; Fronti, J.G. Social innovation indicators. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Strengthening social innovation in Europe. Journey to Effective Assessment and Metrics [Electronic Version] 2012. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/innovation/files/social-innovation/strengthening-social-innovation_en.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- European Commission. Guide to social innovation. Regional and urban policy/employment, social affairs and inclusion. [Electronic Version]. 2013. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/presenta/social_innovation/social_innovation_2013.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mosey, S.; Wright, M. From Human Capital to Social Capital: A Longitudinal Study of Technology-Based Academic Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2007, 31, 909–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alles, M.; Camelo-Ordaz, C.; Franco-Leal, N. Key resources and actors for the evolution of academic spin-offs. J. Technol. Transfer 2015, 40, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E. Social networks and psychiatric clients: The personal and environmental context. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1982, 10, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.G.; Collins, C.J.; Clark, K.D. Existing Knowledge, Knowledge Creation Capability, and the Rate of New Product Introduction in High-Technology Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Lockett, A.; Mustar, P.; Knockaert, M. Academic spin-offs, formal technology transfer and capital raising. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 609–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W. A Heuristic Method for Estimating the Relative Weight of Predictor Variables in Multiple Regression. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2000, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.W.; Lebreton, J.M. History and Use of Relative Importance Indices in Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benneworth, P.; Cunha, J. Universities’ contributions to social innovation: Reflections in theory & practice. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 18, 508–527. [Google Scholar]

- Lejpras, A. How innovative are spin-offs at later stages of development? Comparing innovativeness of established research spin-offs and otherwise created firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzani, D.; Fini, R.; Grimaldi, R. The Internationalization of Academic Spin-Offs: Evidence from Italy. In Process Approach to Academic Entrepreneurship: Evidence from the Globe; Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2017; Volume 4, pp. 241–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, T.; Puri, M. Venture Capital and the Professionalization of Start-Up Firms: Empirical Evidence. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Holzhauer, H.; Dai, Y. Finance or philanthropy? Understanding the motivations and criteria of impact investors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 419–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethic. 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Carthy, B. From fishing and factories to cultural tourism: The role of social entrepreneurs in the construction of a new institutional field. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social value creation through tourism enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CYD Report. Fundación Conocimiento y Desarrollo. 2018. Available online: http://informecotec.es/media/Informe-Cotec_2018_versi%C3%B3nweb.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- III Innovation Social Perception Survey. Fundación COTEC para la Innovación. [Electronic Version] 2020. Available online: http://informecotec.es/metrica/percepcion-social-de-la-innovacion/ (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Wagner, M.; Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Fichter, K. University-linked programmes for sustainable entrepreneurship and regional development: How and with what impact? Small Bus Econ. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M.; Marlow, S. A preliminary investigation into networking activities within the university incubator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeiro, P.R.; López, S.F.; González, L.O.; Sandiás, A.R. Factores determinantes de la creación de spin-offs universitarias. Revista Europea Dirección Economía Empresa 2010, 19, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Burg, E.; Romme, A.G.L.; Gilsing, V.A.; Reymen, I.M.M.J.; Romme, G. Creating University Spin-Offs: A Science-Based Design Perspective. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algieri, B.; Aquino, A.; Succurro, M. Technology transfer offices and academic spin-off creation: The case of Italy. J. Technol. Transfer 2013, 38, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E.; Mosey, S.; Wright, M. The Evolution of Entrepreneurial Competencies: A Longitudinal Study of University Spin-Off Venture Emergence. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1314–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamidass, P.M. University startups as a commercialization alternative: Lessons from three contrasting case studies. J. Technol. Transfer 2013, 38, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Barile, S.; Farioli, F.; Orecchini, F. Strengthening the science–policy–industry interface for progressing toward sustainability: A systems thinking view. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, V.; Piccaluga, A. Exploitation and diffusion of public research: The case of academic spin-off companies in Italy. R&D Manag. 2000, 30, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Zhou, C. Triple Helix twins: Innovation and sustainability. Sci. Public Policy 2006, 33, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Bruneel, J.; Mahajan, A.; Wright, D. Creating value in ecosystems: Crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M.; Kattel, R.; Ryan-Collins, J. Challenge-Driven Innovation Policy: Towards a New Policy Toolkit. J. Ind. Competition Trade 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COTEC Report. Innovación en España. Fundación COTEC para la Innovación. 2017. Available online: http://cotec.es/media/INFORME-COTEC-2017_versionweb.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Rubio de las Alas-Pumariño, T. Recomendaciones Para Mejorar el Modelo de Transferencia de Tecnología en Las Universidades Españolas; Conferencia de Consejos Sociales de las Universidades Españoles: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. From market fixing to market-creating: A new framework for innovation policy. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion with Case Studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] Social innovation | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.11 | 1.02 |

| [2] Frequency of contact with national customers, suppliers and competitors | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.81 | 1.32 |

| [3] Frequency of contact with international customers, suppliers and competitors | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.36 | 1.33 |

| [4] Frequency of contact with national and international VCs | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.43 | 0.83 |

| [5] Frequency of contact with national and international government institutions | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.70 | 0.83 |

| [6] Frequency of contact with national and international TTOs | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.53 | 0.76 |

| [7] Frequency of contact with national and international university institutions | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| [8] Age | 1.00 | 15.00 | 6.47 | 3.89 |

| [9] Type of market | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.12 | 0.33 |

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [9] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 1.00 | ||||||||

| [2] | 0.04 | 1.00 | |||||||

| [3] | 0.19 * | 0.55 ** | 1.00 | ||||||

| [4] | 0.02 | 0.27 ** | 0.37 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| [5] | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.40 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| [6] | 0.26 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.10 | 0.27 ** | 0.53 ** | 1.00 | |||

| [7] | 0.16 | 0.27 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.51 ** | 1.00 | ||

| [8] | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.15 | −0.09 | 1.00 | |

| [9] | 0.12 | 0.24 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.12 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.16 | −0.07 | 1.00 |

| Variables | Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Error | β | t | α | |

| Constant | −1.042 | 0.411 | −2.533 | 0.012 * | |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.229 | 0.819 |

| Target market | 0.363 | 0.263 | 0.117 | 1.382 | 0.169 |

| Frequency of contact with national customers, suppliers and competitors | −0.104 | 0.074 | −0.138 | −1.408 | 0.161 |

| Frequency of contact with international customers, suppliers and competitors | 0.178 | 0.080 | 0.237 | 2.220 | 0.028 * |

| Frequency of contact with national and international VCs | −0.202 | 0.113 | −0.166 | −1.790 | 0.076 † |

| Frequency of contact with national and international government institutions | 0.233 | 0.130 | 0.191 | 1.784 | 0.077 † |

| Frequency of contact with national and international TTOs | 0.383 | 0.141 | 0.288 | 2.729 | 0.007 ** |

| Frequency of contact with national and international university institutions | −0.102 | 0.105 | −0.100 | −0.972 | 0.333 |

| F | 3.26 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.163 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.113 | ||||

| Variables | 95% Confidence Interval | 90% Confidence Interval | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Zero-Order | Partial | Semi-Partial | |

| Age | −0.038 | 0.048 | −0.031 | 0.041 | 0.035 | 0.020 | 0.018 |

| Target market | −0.157 | 0.882 | −0.072 | 0.798 | 0.089 | 0.119 | 0.109 |

| Frequency of contact with national customers, suppliers and competitors | −0.251 | 0.042 | −0.227 | 0.018 | 0.046 | −0.121 | −0.111 |

| Frequency of contact with international customers, suppliers and competitors | 0.019 | 0.337 | 0.045 | 0.312 | 0.191 | 0.188 | 0.175 |

| Frequency of contact with national and international VCs | −0.425 | 0.021 | −0.388 | −0.015 | 0.029 | −0.153 | −0.141 |

| Frequency of contact with national and international government institutions | −0.025 | 0.491 | 0.017 | 0.449 | 0.272 | 0.152 | 0.0141 |

| Frequency of contact with national and international TTOs | 0.106 | 0.661 | 0.151 | 0.616 | 0.277 | 0.229 | 0.0216 |

| Frequency of contact with national and international university institutions | −0.309 | 0.105 | −0.275 | 0.072 | 0.140 | −0.084 | −0.077 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franco-Leal, N.; Camelo-Ordaz, C.; Dianez-Gonzalez, J.P.; Sousa-Ginel, E. The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030906

Franco-Leal N, Camelo-Ordaz C, Dianez-Gonzalez JP, Sousa-Ginel E. The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030906

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranco-Leal, Noelia, Carmen Camelo-Ordaz, Juan Pablo Dianez-Gonzalez, and Elena Sousa-Ginel. 2020. "The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030906

APA StyleFranco-Leal, N., Camelo-Ordaz, C., Dianez-Gonzalez, J. P., & Sousa-Ginel, E. (2020). The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs. Sustainability, 12(3), 906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030906