Learnings from Local Collaborative Transformations: Setting a Basis for a Sustainability Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

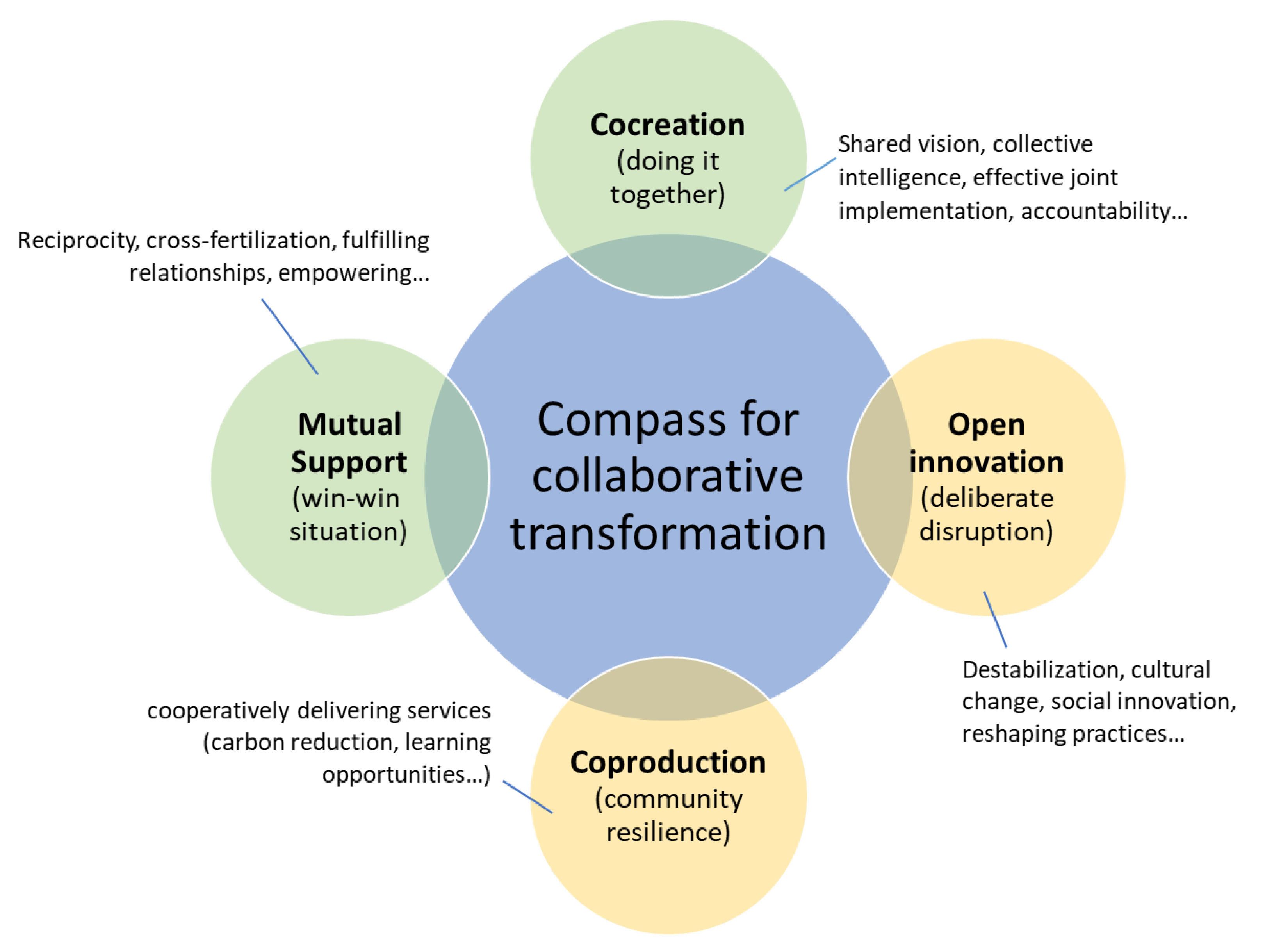

2. Local Transformative Collaborations

3. Methods

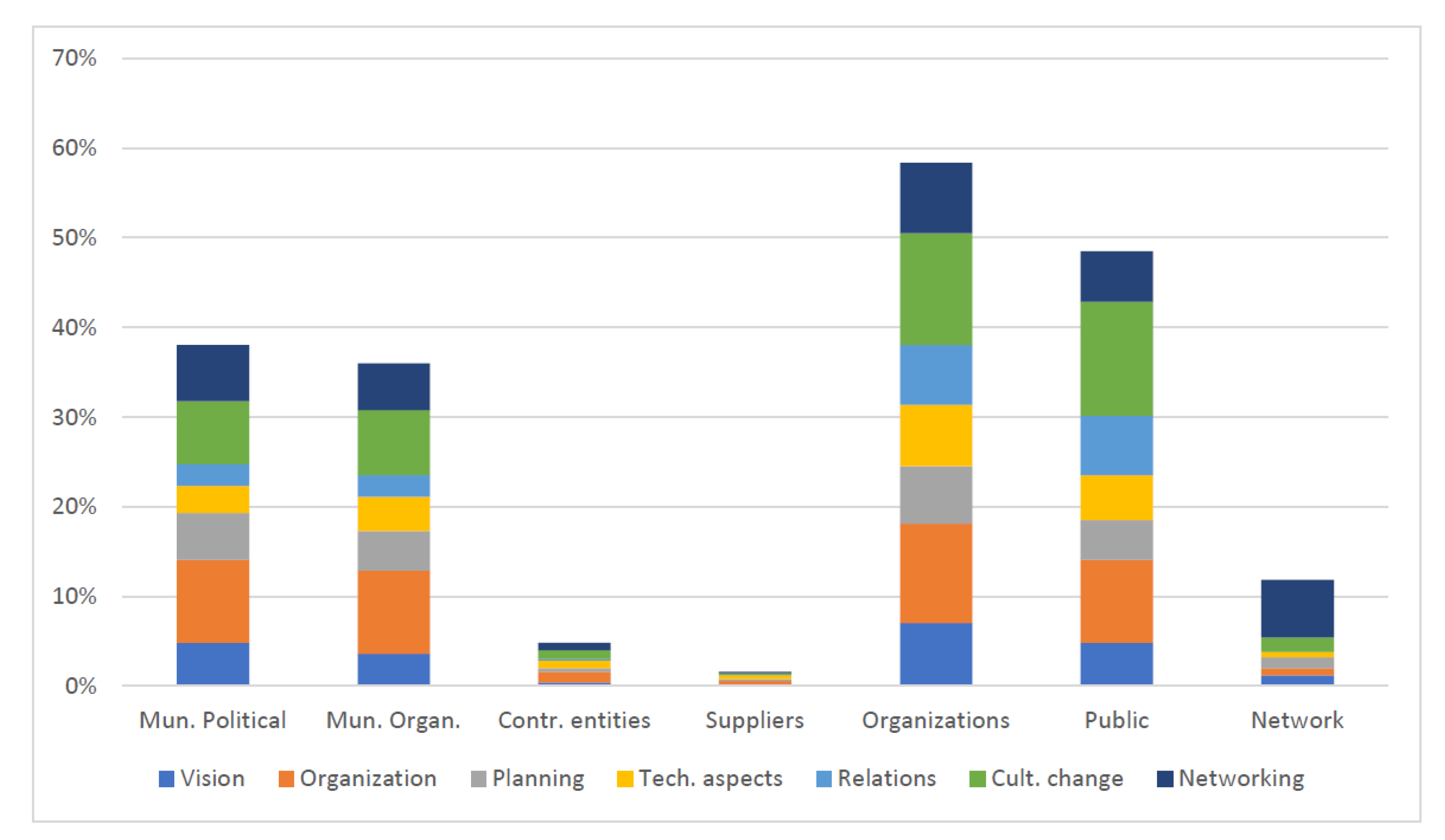

- Municipality, political level: Who institutionally contributes to defining policies, e.g., council, commissions, parties

- Municipality, organizational structure: Technicians and other civil servants responsible for performing municipal functions

- Controlled entities: Entities that are in some way controlled by the municipality

- Suppliers: Public and private suppliers of the municipality

- Organizations: Economic, social, and cultural organizations, profit and non-profit (e.g., business, schools, environmental organizations)

- Public: Families and citizens

- Networks: Other municipalities and actors outside the territory (e.g., other municipalities, levels of government, partners in international networks)

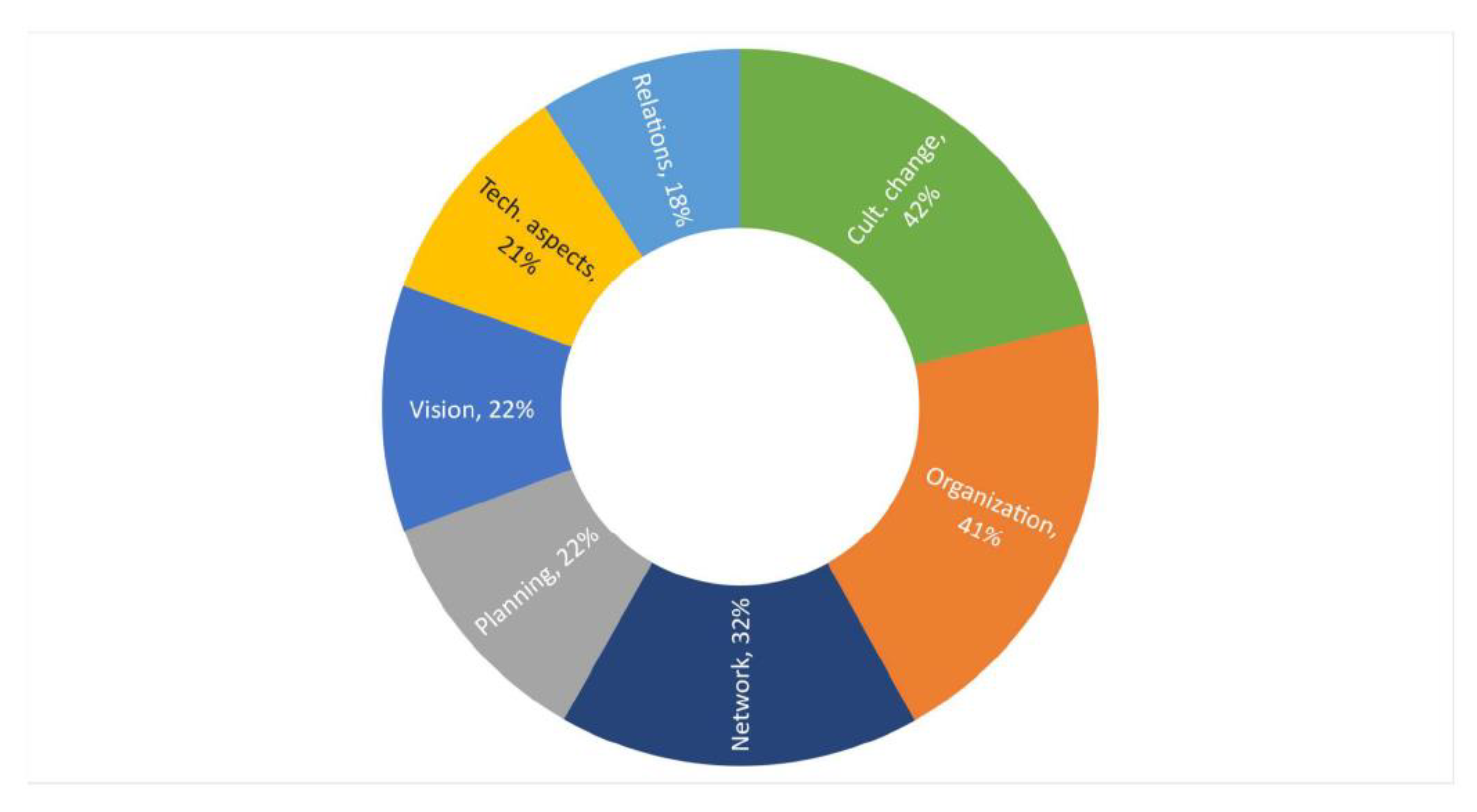

- Vision: Actions and processes that tend to create a vision

- Organization: Actions and processes that tend to create or modify the governance, procedures, roles, and related issues (e.g., creating a new office to deal with sustainability issues)

- Planning: Actions and processes that tend to create a plan (e.g., setting goals, policies integrations, budgets)

- Technical aspects: Actions that modify the system through technology

- Relations: Actions and processes that want to create or improve relationships, namely acting on human and social aspects

- Cultural change: Actions and processes that aim to lead to a ‘paradigm shift’ (including communication and educational activities)

- Networking: Actions and processes that aim to create stable connections and comparisons (e.g., benchmarking)

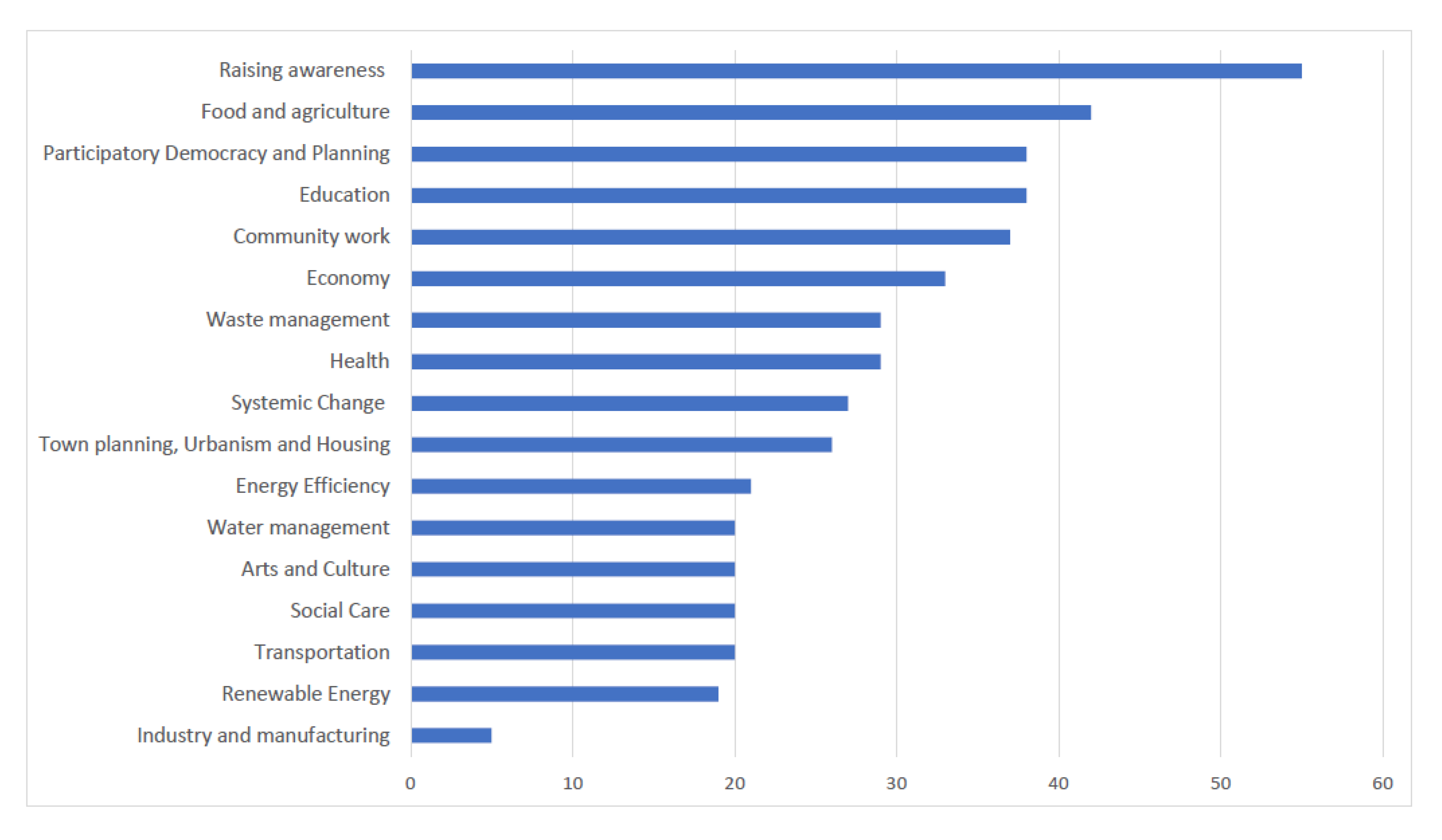

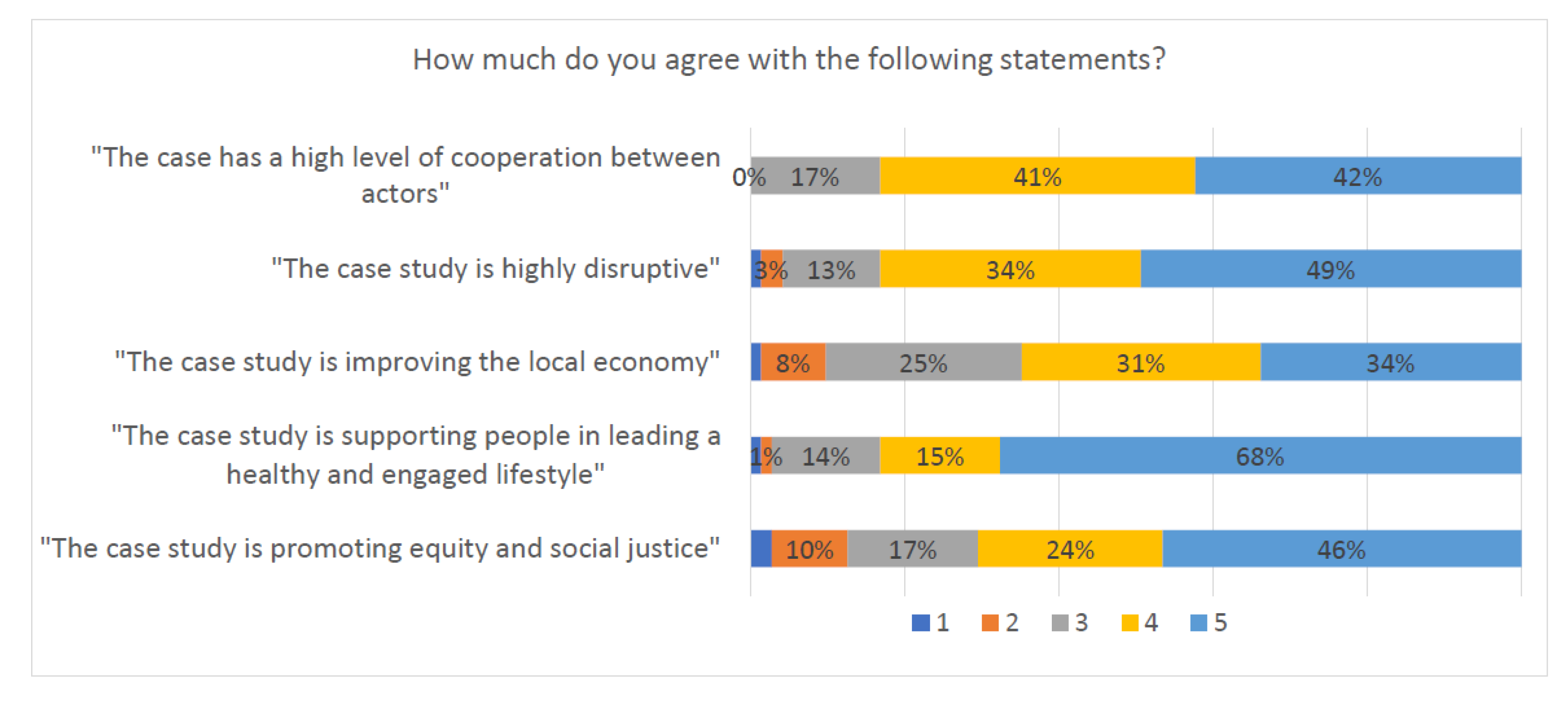

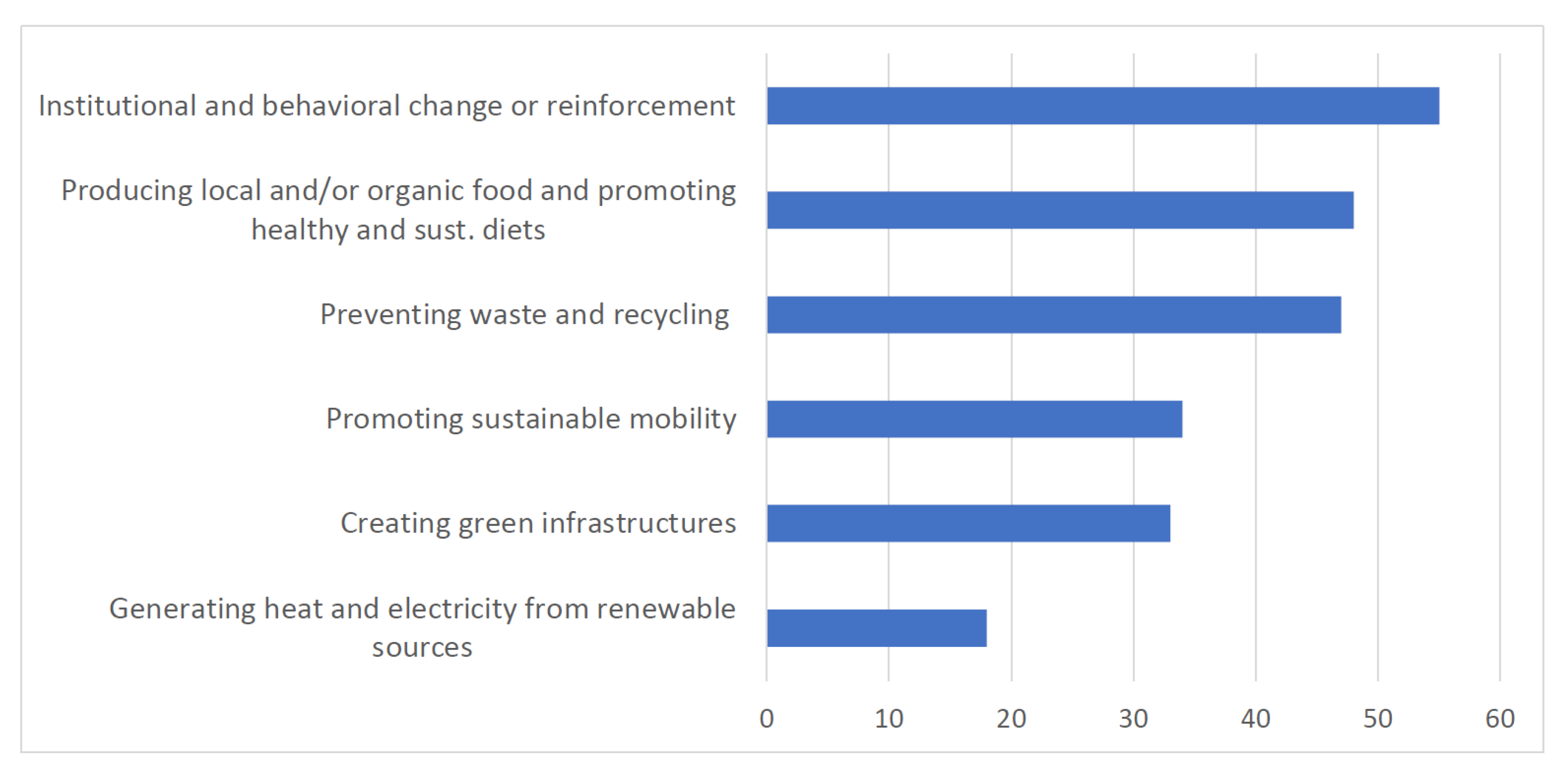

4. Results

4.1. Deeper Analysis of Eight Case Studies

4.1.1. Cocreation

4.1.2. Mutual Support

4.1.3. Coproduction

4.1.4. Open Innovation

5. Discussion

5.1. Preconditions for a Sustainability Framework

- 1.

- Easily adaptable to a wide variety of very different contexts

- 2.

- Simple enough to be relatively easy to learn and to use in real life

- 3.

- Low level of requirements for implementation

- 4.

- Suitable for use in a context of shared/diffused governance

- 5.

- Implementable both in top-down and bottom-up approaches

- 6.

- Support a relational perspective on sustainability

- 7.

- Powerful enough to cope with high levels of complexity and uncertainty

- 8.

- Make good use of existent tools and resources

- 9.

- Able to hold the dimensions of cocreation, mutual support, coproduction, and open innovation.

5.2. Basic Design

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name of the Case Study | Country | Location | Grid Score | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAED—Plan d’action énergie durable (Convenance of the Mayor) | Belgium | Ath, Hainaut | 27 | The Town is building an action plan to decrease CO2 emissions and to build sustainable energy systems. |

| Halle aux Saveurs—Local Producers Market | Belgium | Soignies, Hainaut | 18 | Monthly local producers’ market, with focus on artisanal production, geographical proximity (about 20 km around Soignies) and conviviality. |

| La Ruche qui dit Oui (The food assembly) | Belgium | not defined | 6 | City connects with farmers for good, fresh and healthy food and farmers meet the citizens for sharing knowledge and understanding. |

| Cre@farm + Liège district territorial development scheme | Belgium | Liège | 41 | CATL (bottom-up transition initiative) collaborating with municipalities for access to agricultural land and other resources. |

| Ecobairro São Paulo | Brazil | São Paulo | 34 | Transition to a local, circular, and participatory governance in which community members are encouraged to act responsibly and consciously. |

| Bairro Vivo Project | Brazil | Grajaú, Rio de Janeiro | 36 | Neighborhood project promoting the awakening of individual consciousness and the preservation of the planet and its biodiversity. |

| Balloon Latam | Chile | 10 municipalities in 3 regions | 32 | Development of local economies in a dynamic of shared creation between change agents, social entrepreneurs, municipalities, universities, and other institutions. |

| Challenge in search of an eco-neighborhood | Chile | Bancaria and Santa Elena, Macul, Santiago | 13 | Eco-neighborhood: In every house a garden, every neighbor a recycler. |

| Transition Rukapillan | Chile | Kurarrewe, Panguipulli, VIllarrica and Pucón (4 municipalities) | 28 | Linking and strengthening of sustainable initiatives in an area that is a world-renowned touristic destination surrounded by a rich indigenous cultural heritage. |

| Santiago en Transición | Chile | Santiago de Chile (multiple Municipalities) | 14 | Unifying the collective genius to remember that we are paradise on earth. |

| Escuelas de Vida (Schools of Life) | Colombia | Manizales | 37 | Union of different organizations, foundations, collectives, and Transition initiatives from Manizales that join forces around a common purpose. |

| Community Living Classes | Colombia | San Miguel, San Francisco, Cundinamarca | 13 | The living classroom is an intervention to strengthen the community tissues in favor of sustainability and good living. |

| Nashira a song of love project for peace | Colombia | Palmira, Bolo San Isidro. | 25 | Ecovillage—Nashira a sustainable model of peace led by women for a better quality of life. |

| Promotion of healthy lifestyle challenges of formation for the reception of childhood | Colombia | Arauca, Palestina, Caldas. | 9 | Generate new teaching and learning possibilities that make visible the transformation of healthy lifestyles as a meaning of education. |

| 7RíosFest of Asociación 7Ríos | Colombia | Cali | 15 | Making river protection and river basin regeneration of the seven rivers in Cali fashionable. |

| Uelkom | Colombia | Manizales Caldas | 18 | Social innovation project towards the transformation of the reality in vulnerable contexts, based on ethnography and models of communication. |

| Madre Kumbra—Ecovillage | Colombia | Manizales, Caldas | 26 | Madre Kumbra: Territory for meeting, understanding and sharing with yourself, the other and Nature. |

| Conservation and sustainable production for the collective “good living” | Colombia | San Carlos and San Rafael, Antioquia. | 36 | Creating sustainable development in socially and culturally diverse rural community, around biodiversity conservation. We seek to unite. |

| Det Fælles Bedste (The common best) | Denmark | Vejle | 21 | A convergence on solutions for a green sustainable organic transition. |

| The Impact Farm | Denmark | Nørrebro | 30 | Designing an ambitious urban greenhouse as a Hub for transition. |

| Transition Town Silkeborg—The Local Bicycle Infrastructure Plan | Denmark | Silkeborg | 22 | Collaboration between organizations and municipality to deliver a local bicycle plan. |

| La filière de la graine à l’assiette (The process of the seed to the plate) | France | Ungersheim | 14 | Short circuit for production of organic food, in a wide context of transition. |

| Short supply chains House | France | Sucy-en-Brie, Val-de-Marne, Ile-de-France, France | 14 | A market hall for local food just born in a collaboration between municipality and associations. |

| Vélo-école | France | Ménilmontant, 20ème arrondissement, Paris | 11 | Teaching adults to cycle—can be a source of autonomy and freedom for adults who never learned when they were younger. |

| Zukunftsstadt Dresden 2030+ (future city Dresden 2030+) | Germany | Dresden, Saxony | 43 | Involving the people of Dresden into a strategic transition-process from visioning via planning to action and transformation, with scientific monitoring. |

| Stadtgärtle | Germany | Esslingen | 13 | Promoting a public green space to grow vegetables with the neighborhood. |

| Transition Wekerle | Hungary | Wekerle, Kispest, Budapest | 25 | A transitioner trainer was elected as councilor and promotes sustainability issues. |

| Comune di Santorso | Italy | Santorso (Vicenza) | 18 | Facilitating the access of the public to technologies like renewables. It also promotes the integration of refugees, which is a distinctive feature. |

| Energy Function | Italy | Emilia Romagna Region | 19 | Development of a theoretical and operative framework to address “sustainability and resilience” at local government level in a systemic way. |

| Livorno | Italy | Livorno (City) | 22 | Emerging new relationship between local government and citizens searching for new methodologies and tools to develop and thrive. |

| La Coope-Comunidad de Intercambio Ecológico y Solidario | Mexico | Querétaro | 24 | A recent cooperative-community dedicated to the local food system. |

| Asociacion Projungapeo: JET (Jungapeo en Transición) | Mexico | Jungapeo, Michoacán | 40 | An ongoing community project seeking an integral local development. |

| Bacalar en transición | Mexico | Bacalar, Quintana Roo | 21 | Working together to protect the lagoon of Bacalar and the communities that live here. |

| El Itacate | Mexico | Tepoztlán, Morelos | 19 | Transition Reconomy project based in Tepoztlan settled as a think tank lab for helping food gardening, permaculture and educational projects. |

| Architecture for sustainability | Mexico | Guadalajara Jalisco | 18 | Social enterprise oriented to sustainable architecture and dissemination of tools for resilience. |

| Achterhoekse Groene Energie Maatschappij (Achterhoek Green Energy Cooperative—AGEM) | The Netherlands | Achterhoek (region) | 29 | Regional energy cooperative owned and managed by municipalities. |

| Buurtfonds Dichters-Rivierenwijk (Neighbourhood Fund) | The Netherlands | Dichters and Rivieren, Utrecht | 8 | Neighborhood initiative fund aimed at distributing small grants. |

| The Aardehuis project | The Netherlands | Olst | 35 | Sustainable living project with 23 houses and a community building; municipality, transition initiatives, and other partners are involved. |

| Blue City | The Netherlands | Rotterdam | 24 | Breeding ground in Rotterdam for innovative companies that try to connect their loops together: One company’s output is another company’s input. |

| Parceria Local de Telheiras (Local partnership) | Portugal | Telheiras, Lumiar, Lisbon | 43 | Neighborhood partnership that resulted from a transition initiative and a local agenda 21 promoted by the municipality. |

| Coimbra em Transição | Portugal | Coimbra | 25 | Designing a local hub for transition. |

| Zero Waste Village | Spain | Orendain, Gipuzkoa | 14 | Project based on waste management/circular economy. |

| La Garrotxa Territori Resilient | Spain | Garrotxa (21 Municipalities) | 36 | Rural region that is home to 21 municipalities and over 500 local community organizations that work together towards a sustainable and well-networked society. |

| Mares Madrid | Spain | Province of Madrid | 48 | Urban transformation by promoting social economy and collaboration (energy, recycling, food, mobility, and social care economy). |

| Almócita, semilla en transición | Spain | Almócita, Almería, Andalucía | 30 | Municipality actively participating in the transition movement, in aspects such as energetic self-sufficiency, composting, and car-free. |

| Iniciativa Rubí Brilla | Spain | Rubí, Barcelona, Catalunya | 35 | Local strategy to change the energetic model, promoting energy saving and energy efficiency in all the sectors of the city. |

| Descarboniza! Que non é pouco | Spain | Santiago de Compostela, Galicia | 19 | Organize and give support to groups of people who are willing to “decarbonize” their lifestyles. |

| La Colaboradora | Spain | Zaragoza | 33 | First coworking P2P that promotes a collaborative economy in the city through a time bank of voluntary exchange of services and knowledge. |

| Citizen initiative to improve people´s lives in the municipality | Spain | Quéntar, Granada | 19 | Citizen education for improving community living. |

| Comunidades en transición | Spain | Zarzalejo, Madrid | 26 | Transition Initiatives, CSA, collective space, transportation, waste management, participatory budgets. |

| Red Huertos Urbanos Comunitarios | Spain | Madrid | 39 | Many small gardens will grow small people who will change the cities. |

| Turuta Social currency | Spain | Vilanova i la Geltrú | 29 | Promoting collective citizenship projects, including social currency. |

| Sierra Oeste Agroecologica | Spain | Sierra Oeste de Madrid (19 Municipalities) | 24 | Regional partnership for agroecological development. |

| Montequinto (Dos Hermanas) | Spain | Seville | 14 | Permaculture project for local resilience. |

| Jaén en Transición | Spain | Jaén | 37 | Transition Initiative. The project opts for local initiatives that are moving towards economic degrowth and good living. |

| Murcia IT - Innovación y Tradición | Spain | Murcia | 35 | Participatory Integrated Sustainable Urban Development strategy. |

| Implementation of the local digital currency in the context of intelligent public spending | Spain | Santa Coloma de Gramenet, Barcelona, Cataluña | 37 | Local currency to promote social and democratic economy. |

| Móstoles en Transición | Spain | Móstoles | 29 | Transition initiative with the participation of the municipality; implementation of a new city model that faces the ecosocial challenges. |

| Vilawatt | Spain | Viladecans, Barcelona | 31 | Reduction of energy consumption with innovative tools (local currency). |

| Växjö | Sweden | City | 38 | More than 30 years of work on sustainability. |

| Air quality: An engaging narrative | United Kingdom | Southampton | 40 | Concerns about poor local air quality and health have helped create closer collaboration between local officials, councilors and groups of residents. |

| Caring Town | United Kingdom | Market Town of Totnes (and surrounding district), South Hams, Devon | 45 | Local network of public, voluntary and private organization coming together to pool resources, skills and ideas. |

| Pollinator Preservation | United Kingdom | Monmouthshire | 18 | Preserving bees in a transition context. |

| Town Orchards | United Kingdom | Chepstow | 15 | The planting of orchards on town council land giving the community the opportunity to pick sustainably grown local fruit. |

| Walking Bus | United Kingdom | Chepstow | 17 | The creation of a walking bus to encourage school children to walk to school reducing emissions and creating a healthier lifestyle. |

| Climate Protectors | United States of America | Sonoma County, California | 35 | The “climate protectors” is a well-structured collaboration in terms of promoting climate action, both from public and governments, with seven years of experience. |

| Sanctuary School | United States of America | Milwaukee | 10 | Promoting healing arts with public, special “underserved communities” and “minorities.” Creativity seems to play a great role. |

| Transition Centre Emerging Sustainability Culture | United States of America | Centre County, Pennsylvania | 45 | The project´s focus is on promoting a shared vision, planning, and networking. They give great importance to economy. |

| Compost pickup in Media PA | United States of America | Media, Pennsylvania | 19 | Recycling food waste in a transition context and collaboration with municipality. |

| Transition Streets pilot project - Des Moines Climate Action Plan | United States of America | Des Moines, Iowa | 30 | Climate Action Plan with a transition context. |

| Building Community Resilience through Grassroots and Government Collaborations | United States of America | Sonoma, California | 59 | Decade of successful collaboration between grassroots and local government that catalyze wide-scale community action. |

Appendix B

| Case History | Governance Model | Policies and Tools | Work in Progress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Acts, Sonoma, United States of America | Founded in 2002, Daily Acts (DA) is an educational NGO whose purpose is to be a catalyst for personal and community transformation. After running community-based sustainability education programs for five years, DA recognized that partnering with LGs was a critical pathway to build organizational capacity and affect systemic change. Meanwhile LGs recognized that DA could offer (1) a unique ability to engage the community; (2) sustainability expertise; (3) operating in a cost-effective way. The first contract for a joint educational program was signed with the city of Petaluma in 2007 and others followed. The main barrier initially was valuing DA’s services. | Government partnerships are based on regular yearly financial contracts to implement sustainability programs. DA engages sustainability experts and a wide range of non-profits, businesses, government agencies, and other organizations across the gamut of sustainability-related issues. DA works with approximately a dozen different alliances and networks. Beyond flattening leadership and moving it to the edges of the organization and working in coalitions, DA is moving in a programmatic direction that more deeply engages the leadership of communities. | DA was born out of a permaculture design approach with the underlying ethical principles of earth care, people care, and fair share, and the primary methodology being to take an integrated and holistic approach. DA work with government agencies is a core strategy to affecting wide-scale community transformation while building organizational and movement capacity in the community resilience field. Some of the core operating principles are (1) shared leadership; (2) nurturing non-profit networks; (3) working with business and government; (4) doing both program implementation and advocacy work. | DA promotes ‘homegrown programs’ transforming homes and landscapes into productive, resilient ecosystems—educational tours expose people to inspiring and practical examples; workshops help people develop practical skills; garden installations and landscape transformations help people work together to create practical acts of transformation. ‘Community Resilience Challenge’ is an annual campaign to inspire wide-scale collaborative action. Activities promoted range from planting fruit trees to installing greywater and rainwater catchment systems to committing to reduce waste, shop local, and hosting neighborhood potlucks. |

| Ecobairro, São Paulo, Brazil | Inspiration to Ecobairro came from educational experiences related to Ecovillages (2004). The initial founders (Lara Freitas and Paulo Santos) got together with other people and presented the program in 2005, receiving institutional support from the City Council and United Nations. Biggest challenge in the beginning was the lack of public awareness. The program is now also operating in Salvador and Feira de Santana. | Ecobairro is an enduring program from the Roerich Institute of Peace and Culture of Brazil. In São Paulo it is hosted by the organization Casa Urusvati. There is a structure of coordinators, advisers, and nucleators, with a systemic approach to leadership. Decision-making is always in group. | Focus on urban sustainability and eco-neighborhoods, while connecting different levels, from personal to planetary. Project is grounded in the ‘mother’s pedagogy,’ based on an analogy with motherhood (fostering values as deep inclusion, care, intuition, openness, and flexibility). Use tools like Nonviolent Communication or Open Space and the framework of SDG. | Activities include recruitment of volunteers; active dialogues with local agents and universities; campaigns, trainings, exhibitions, and workshops on environmental practices and topics; networking with the Global Ecovillage Network and Transition Movement; collaborating in local public initiatives like UMAPAZ (Open University for Environment and Culture of Peace) and Municipal Council for Environment and Sustainable Development. |

| Energy Function, Emilia Romagna, Italy | In 2008 “Monteveglio Città di Transizione” was the first Transition Initiative in Italy and started its activity with a quite visible, official and unusual strategic partnership with the Municipality. Together they led action on the Covenant of Mayors and succeeded in involving the whole ‘Unione di Comuni’ (6 municipalities). This was the basis for a partnership with the regional branch of ANCI (National Association of Municipalities), in 2009, aimed at replicating this example and create support tools. CURSA (University Consortium for Socioeconomic and Environmental Research) joined the effort on the behalf of the national Environmental Ministry. After a few years of experiments was evident the need of a general framework to make easier the day by day challenges posed by the complexity of the different contexts. | It is believed that energy issues (and the necessary transition to a low-carbon economy) brings new challenges to local governance and should be included as a new municipalities’ function (changing legislation). The Energy Function (EF) should be a local policy transversal to all existent policies; focused on facilitation and support of families and businesses; grounded in multi-level governance; strictly dependent on the peculiarities of the territory (natural and social capital); urgent while having a medium-long term perspective. | The principle for designing the EF were: having a general, systemic framework easy enough to be understood with a simple learning curve and having a way to organize all the available tools, methodologies and needed information for those trying to work in the field. In spite of the name, the actual model for the EF can hold much more than “energy issues” being a systemic tool strongly inspired by the Transition work, system thinking, and various theories of change approaches. It has a stochastic design. | The Energy Function approach is based on a relationship grid that holds the “scenario” and an intended pattern language database that contains tools and needed information. All is designed to be practical and grounded on reality but without simplifying the complex environment and set of conditions and relationships real life presents. The EF was indicated as a necessary tool on the Regional Energy Strategy of Emilia Romagna but kept underdeveloped. |

| Future City Dresden 2030+, Dresden, Germany | In 2015, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) launched the Future City for Sustainable Development competition. Three phases were considered: (1) Development of a common vision; (2) planning; (3) implementation. Dresden’s government decided to apply in 2015 and is one of the seven finalists going for phase 3 in 2019, receiving around one million euros for that purpose. | The process is driven by the municipality through a project manager who formed a ‘Future City team.’ First project partners were two scientific bodies, the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development and the Knowledge Architecture at the University of Dresden (with experience in designing processes for working with people). In phase 2 other partners joined (e.g., public transport company and energy provider) and a group was formed. Involvement was restricted to some meetings and a conference. Stronger collaborations are expected in phase 3, with joint implementation of projects. People from civil society were involved and there is a sense of excitement with the possibilities to collaborate. | The initiative follows the inspiration from the Transition Movement, empowering people to act at their own places, creating rooms where they can meet (“people own the city, and they should be the ones developing it”). In this way, it is considered a pioneering project in the government. Discussion rooms have been streamlined to support people in the process of creating projects. For example, identifying objectives, problems to solve, useful personal experiences and skills, evaluation criteria, etc. | The initiative concentrates on the process as designed by BMBF, following what was included in the application. In this phase (2) efforts are directed to codesigning projects. Although this planning phase is considered too abstract by some participants, it is believed that it is affecting how people face sustainability issues and their own role in the city. Stronger connections are believed to be the greatest outcome at this stage. A catalogue was prepared with all the ideas relating to education, campus and citizen knowledge; neighborhood; energy; sustainable economy and business model; mobility; urban space; citizen participation; culture and capital of culture. |

| Jungapeo en Transición, Jungapeo, Mexico | The NGO ‘Pro Desarrollo Integral del Municipio de Jungapeo’ was created in 2015 (grassroots’ activities started in 2005), focused in local, integral development. In 2016 the local mayor challenged the NGO to transform Jungapeo into the first official Transition town in México, which led to a signed agreement. Barriers are mistrusted based on previous bad experiences; apathy by the population; short exercise of power of the municipal authorities; lack of continuity due to overwork. | Jungapeo en Transición (JET) is managed by a full-time staff dependent on the CBI. It is grounded in a matrix organization with three axes (social, agriculture, and tourism) and five components that interact with the axes (ecology, culture, health, education, and sports). Collaboration with municipality is supported by regular briefings and by inviting members of the municipality to workshops and activities. Local agents are involved, also through focal groups (children, students, business, teachers, elders). | Inspiration comes mainly from the Transition Movement. It intends to “eradicate the mentality of assistencialism and dependency” and empower the community to identify their needs and help to resolve them. Collaboration between LGs and CBIs is expected to grow based on trust and confidence arriving from joint successful activities—small initial steps with big visibility. Tools like sociocracy, coaching, and Robert’s Rules of Order are used to foster inclusion and participation. | Organized activities range from cleaning rivers to competitions to honoring the dead (embedded in Mexican culture), local markets to dry toilets. An educational approach is the focus, including workshops for elders, youth and other groups. Regardless of the several results that have emanated from own projects, they have been able to observe recent “outbreaks” of spontaneous and orderly teamwork among the local population, “as if the Transition Effect were contagious.” Monitoring includes regular and extensive surveys to partners, beneficiaries and public. |

| MARES, Madrid, Spain | The economic crisis of 2008 increased unemployment and urban social-spatial segregation. Dinamia (social consulting) joined the municipality, Tangente and Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas (two collaborative platforms) with the idea of supporting existent CBIs related to social and solidarity economy. Other partners joined the initiative. | MARES is a partnership centralised in the Council. Several partners participate in the executive, economic and finance committee (with voting rights) and steering groups (led by different partners). Control processes were defined, such as management plan, quality plan, risk assessment plan, evaluation system and monitoring, handbook of internal communication and decision making. | The focus is on urban economic resilience. It intends to strengthen the emerging opportunities in strategic sectors (transport, food, waste, energy, and care, MARES in Spanish). It seeks for cooperation among local actors, social innovation and the active productive involvement of citizens. The base is to “put the people before the profit.” Use tools like the co-design for the reuse of disused buildings and public spaces; mapping citizens’ competencies; analysis of care needs and proposal for value chain; learning communities. | Initiatives of collective self-employment by means of increase awareness, training and support to citizen groups. The biggest challenge is the generation of real participatory public policies in the functional and social fields. There are expects outcomes like a change of transport to low emission models, implementation of renewable energies and energy efficiency, improved care for older people and for the infancy, consume of local products and agroecologic food, hopefully generating employment. |

| Rubí Brilla, Rubí, Spain | In 2008 the Rubí Council joined the Covenant of Mayors, within the European initiative to reduce carbon emissions. A Plan of Action for Sustainable Energies was prepared externally, with the support of Barcelona Council. The Rubí Brilla initiative started in 2011. Angel Ruiz, working for the municipality and private entrepreneur, played a key role by bringing expertise and a business perspective. | Rubí Brilla is a service provided by the municipality and managed by a working group of eight internal technicians. Energy experts have been hired in 2013 and several collaborations are established with external entities. A specific partnership is built with schools and other public organizations, where decisions are taken collectively—in this context savings from investment in energy efficiency are locally reinvested (50% in new measures for energy saving, leading to a positive feedback loop). | The initiative uses the economic factor as the leading motivational factor and prioritizes economic tools commonly used in the business sector. Using the ‘pareto principle’ they focused on energy efficiency in public buildings. Substantial emissions and cost reduction were achieved so ‘profits’ were reinvested in new actions (energy efficiency and renewable energy). The clear cost-cutting is used as an argument to convince private partners. | A major part of the work done relates to the private sector (industry accounts for 40% of emissions). This is mostly done by promoting technical meetings with the biggest energy users, were learnings are shared and support is provided. This includes collaborations with the Polytechnic University of Catalunya. Other activities include providing monitoring apps to families, energy centers at neighborhood level, and buying electric vehicles. Data monitoring is a key activity, including real time checking of consumption and efficiency indicators. Citizens are provided with information on energy costs in public buildings and street lighting. |

| Växjö, Sweden | The municipality saw a need to restore the local lakes in 1969 and the environmental focus has continued since then. In 1993, LG approved a local environmental policy and in 1996 decided to become a fossil fuel-free municipality. In 1999, a Local Agenda 21 strategy for Sustainable Växjö was adopted. In 2006, the LG’s Environmental Program was agreed (updated in 2010 and 2014). Several participatory efforts (polls, meetings…) have been tried but the results were unsatisfactory. | The development has been driven by municipal departments and municipally-owned corporations. Since May 2016 there is a sustainability group which is part of the development unit of the municipal management. The group has two politicians assigned to it and formulates the Environmental Program. It is up to each operation unit to break this down into actionable, budgeted steps with measures related to the goals. | The main principle is to promote a strong political leadership with bold decisions. The basic approach, since 1969, has been a sequence of political decision > steering documents > goals > municipal boards/corporations plans > budgets > follow up> publication in annual report with goal scorecards. To assure continuity three main factors are considered: (1) Consensus among parties; (2) direct involvement of politicians; (3) strong management structure in place. Work is underway to align the program with the SDGs (ready 2019). | The Environmental Program’s measurable goals are planned and monitored through Växjö municipality’s management system. Each municipal steering board and company are responsible for fulfillment of the goals as well as to deliver statistics. The annual report is publicly available. Multiple outcomes are visible, like better air and water quality, green spaces, or sophisticated waste sorting. There is a feeling of pride in being at the forefront of environmental development. |

References

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göpel, M. The Great Mindshift; The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 2, ISBN 978-3-319-43765-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vangen, S. Developing Practice-Oriented Theory on Collaboration: A Paradox Lens. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Pettitt, M.; Wilson, J.R. Factors of collaborative working: A framework for a collaboration model. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781107415379. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Perspectives on Transitions to Sustainability; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-9213-939-1. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; van der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A. Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations towards Sustainability; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 24, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jager, N.W.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.R.; Wiek, A.; Sarewitz, D.; Robinson, J.; Olsson, L.; Kriebel, D.; Loorbach, D. The future of sustainability science: A solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Moug, P.; Allen, S.; Beckmann, K.; Blackwood, D.; Bonaventura, M.; Burnett, K.; Danson, M.; Falconer, R.; Gagnon, A.S.; et al. Transformation in a changing climate: A research agenda. Clim. Dev. 2018, 10, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Dumitru, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Avelino, F.; Bach, M.; Best, B.; Binder, C.; Barnes, J.; Carrus, G.; Egermann, M.; et al. Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.S.; Alves, F.M.; Dinis, J.; Truninger, M.; Vizinho, A.; Penha-Lopes, G. Climate adaptation, transitions, and socially innovative action-research approaches. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropotkin, P. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, O.S.; Mullins, D.A.; Whitehouse, H. Is It Good to Cooperate? Testing the Theory of Morality-as-Cooperation in 60 Societies. Curr. Anthropol. 2019, 60, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, A. No Contest: The Case against Competition; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 0395631254. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Collaboration as a pathway for sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesten, E.; Jolink, A.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Chappin, M.; Lozano, R. Sustainable collaboration: The impact of governance and institutions on sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A. Coalitions, Science, and Belief Change: Comparing Adversarial and Collaborative Policy Subsystems. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Wittmayer, J.; Loorbach, D. The role of partnerships in “realising” urban sustainability in Rotterdam’s City Ports Area, the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Panacea or paradox? Cross-sector partnerships, climate change, and development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, L.; Broto, V.C. Climate governance through partnerships: A study of 150 urban initiatives in China. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huijstee, M.M.; Francken, M.; Leroy, P. Partnerships for sustainable development: A review of current literature. Environ. Sci. 2007, 4, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergragt, P.J.; Quist, J. Backcasting for sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Iwaniec, D. Quality criteria for visions and visioning in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, D.C. Pathways to Climate Change Adaptation: Making Climate Change Action Political. Geogr. Compass 2016, 10, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Rockström, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming Innovation for Sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management, New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development; International Books: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-90-5727-057-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydin, Y.; Pennington, M. Public Participation and Local Environmental Planning: The collective action problem and the potential of social capital. Local Environ. 2000, 5, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Salverda, I.; Vaandrager, L.; van Dam, R.; Wentink, C. Relationships between green urban citizens’ initiatives and local governments. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TESS. Final Publishable Summary Report; European Research Project TESS (Towards European Societal Sustainability): Potsdam, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BASE. Key Policy Issues in Implementing and Evaluating the EU Adaptation Strategy; Research Project BASE Bottom-Up Climate Adaptation Strategies Towards a Sustainable Europe: Aarhus, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henfrey, T.; Penha-Lopes, G. Policy and community-led action on sustainability and climate change: Paradox and possibility in the interstices. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2018, 29, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, P.; Henderson, C. Operationalising a framework for understanding community resilience in Europe. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Bosman, R.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Akerboom, S.; Boontje, P.; Hoffman, J.; Paradies, G.; Pel, B.; Scholten, D.; Wittmayer, J. The (Self-)Governance of Community Energy: Challenges & Prospects; DRIFT: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin, F.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Abel, N.; Clark, W.C.; Olsson, P.; Smith, D.M.S.; Walker, B.; Young, O.R.; et al. Ecosystem stewardship: Sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amundsen, H.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Aall, C.; Karlsson, M.; Westskog, H. Local governments as drivers for societal transformation: Towards the 1.5 °C ambition. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Carmen, E.; Chapin, F.; Ross, H.; Rao-Williams, J.; Lyon, C.; Connon, I.; Searle, B.; Knox, K. Community resilience for a 1.5 °C world. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J. Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy. IFLAS Occas. Pap. 2018, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, P.J.; Sol, J.; Wals, A. Social Learning in a Multi-Actor Innovation Context. In Proceedings of the 9th European IFSA Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 4–7 July 2010; pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Truffer, B. Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: Towards an integrated framework. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M. Policy design without democracy? Making democratic sense of transition management. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijsink, S.; Olivotto, V.; Taanman, M.; Cozan, S.; Weaver, P.; Kemp, R.; Wittmayer, J. Social Innovation Evaluation tool: Critical Turning Points and Narratives of Change; TRANSIT: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Verhees, B. Cultural legitimacy and framing struggles in innovation journeys: A cultural-performative perspective and a case study of Dutch nuclear energy (1945–1986). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 910–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Schoenefeld, J.J. Collective climate action and networked climate governance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Chesbrough, H.; Moedas, C. Open Innovation: Research, Practices, and Policies. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2018, 60, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, E.T. Action Research; Sage Ppublications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4833-0183-9. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.; Alexander, C.; Beale, N.; Brightbill, N.; Cahill, C.; Cameron, J.; Chatterton, P.; Cieri, M.; Coe, C.; Dolan, C.; et al. Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place; Kindon, S., Pain, R., Kesby, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-203-93367-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, M.; Creamer, E. Assessing diversity and inclusivity within the Transition movement: An urban case study. Environ. Polit. 2017, 26, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes-Jesus, M.; Carvalho, A.; Fernandes, L.; Bento, S. Community engagement in the Transition movement: Views and practices in Portuguese initiatives. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1546–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penha-Lopes, G.; Henfrey, T. Reshaping the Future: How Local Communities Are Catalysing Social, Economic and Ecological Transformation in Europe. The First Status Report on Community-led Action on Sustainability and Climate Change in Europe; ECOLISE: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; ISBN 978-2-9602393-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Biddau, F.; Armenti, A.; Cottone, P. Socio-psychological aspects of grassroots participation in the Transition Movement: An Italian case study. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2016, 4, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, N.; Pataki, G. WP4 CASE STUDY Report: The Transition Movement; TRANSIT: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The Transition Town Network: A Review of Current Evolutions and Renaissance. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2011, 10, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Nunes, R. Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the Transition Movement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Pinca, G.; Cavalletti, A.; Bartolomei, M.; Bottone, C. La Funzione Energia nei Comuni e nelle Unioni. In Qualità Dell’ambiente Urbano—X Rapporto—Focus su Le Città e la Sfida dei Cambiamenti Climatici; ISPRA: Roma, Italia, 2014; ISBN 978-88-448-0686-6. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, F.C.; Bentz, J.; Silva, J.M.N.; Fonseca, A.L.; Swart, R.; Santos, F.D.; Penha-Lopes, G. Adaptation to climate change at local level in Europe: An overview. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Park, J.J.; Smith, A. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, O.; Gebhardt, O.; Branth Pedersen, A.; Breil, M.; Campos, I.; Chiabai, A.; Den Uyl, R.M.; Foudi, S.; Garrote, L.; Harmáčková, Z.; et al. Implementation of Climate Change Adaptation: Barriers and Opportunities to Adaptation in Case Studies; BASE: Leeds, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M. Collaboration, Adaptation, and Scaling: Perspectives on Environmental Governance for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Urban Adaptation to Climate Change in Europe 2016—Transforming Cities in a Changing Climate; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2016.

- Turnheim, B.; Berkhout, F.; Geels, F.; Hof, A.; McMeekin, A.; Nykvist, B.; van Vuuren, D. Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, U. Mapping and navigating transitions—The multi-level perspective compared with arenas of development. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, R. Environmental Melancholia—Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781315851853. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, J.; Brown, M.Y. Coming Back to Life: The Updated Guide to the Work that Reconnects; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2014; ISBN 978-1-55092-580-7. [Google Scholar]

- MiT. The MiT Framework for the Pilots. Available online: http://municipalitiesintransition.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/09/MiT-Framework_version-1.1-April-2018-to-be-published.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Bockelbrink, B.; Priest, J.; David, L. Sociocracy 3.0—A Practical Guide. Available online: https://sociocracy30.org/_res/practical-guide/S3-practical-guide-ebook.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2018).

| Actors Categories | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions Categories | Municipality Political | Municip. Organization | Controlled Entities | Suppliers | Organizations | Public | Networks |

| Vision | 24 | 18 | 2 | 1 | 35 | 24 | 6 |

| Organization | 46 | 46 | 6 | 2 | 55 | 46 | 4 |

| Planning | 26 | 22 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 22 | 6 |

| Technical aspects | 15 | 19 | 4 | 2 | 34 | 25 | 3 |

| Relations | 12 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 0 |

| Cultural change | 35 | 36 | 5 | 1 | 62 | 63 | 8 |

| Networking | 31 | 26 | 4 | 1 | 39 | 28 | 32 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macedo, P.; Huertas, A.; Bottone, C.; del Río, J.; Hillary, N.; Brazzini, T.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Penha-Lopes, G. Learnings from Local Collaborative Transformations: Setting a Basis for a Sustainability Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030795

Macedo P, Huertas A, Bottone C, del Río J, Hillary N, Brazzini T, Wittmayer JM, Penha-Lopes G. Learnings from Local Collaborative Transformations: Setting a Basis for a Sustainability Framework. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030795

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacedo, Pedro, Ana Huertas, Cristiano Bottone, Juan del Río, Nicola Hillary, Tommaso Brazzini, Julia M. Wittmayer, and Gil Penha-Lopes. 2020. "Learnings from Local Collaborative Transformations: Setting a Basis for a Sustainability Framework" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030795

APA StyleMacedo, P., Huertas, A., Bottone, C., del Río, J., Hillary, N., Brazzini, T., Wittmayer, J. M., & Penha-Lopes, G. (2020). Learnings from Local Collaborative Transformations: Setting a Basis for a Sustainability Framework. Sustainability, 12(3), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030795