1. Introduction

Tea is the most widely consumed beverage globally, and most tea research has focused on its frequency of use and physiological effects [

1]. However, few studies have focused on the role of tea in hospitality services. In addition to health considerations, personal life habits and cultural factors influence tea consumption. In Taiwan, afternoon tea has gradually become a popular part of social life. Customers care about a restaurant’s environment, ambience, service, and layout, and distinctive afternoon tea restaurants typically appeal to customers.

Hospitality is one of the world’s largest industries, contributing trillions of dollars annually to the global economy and stimulating capital investment [

2]. Each major city in Taiwan (such as Taipei, Taichung, and Kaohsiung) has more than 600 restaurants and hotels that provide afternoon tea service, which generates annual revenue of

$13 billion NTD [

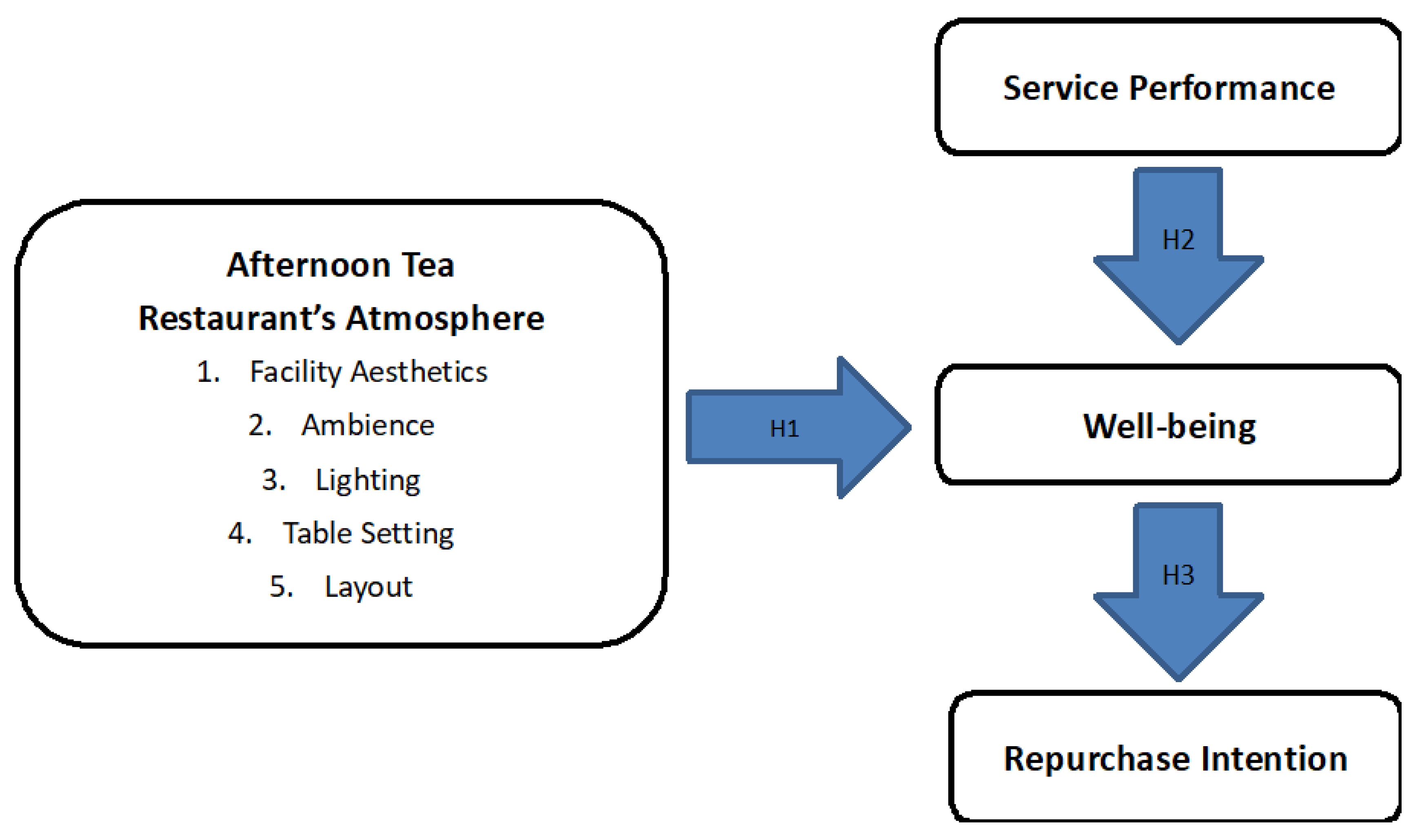

3]. Customers value the hotel restaurant atmosphere. Specifically, restaurant atmosphere and service performance influence customer enjoyment, thereby influencing repurchase intention. The effects of hotel atmosphere on customers are primarily emotional and are difficult to verbalize. Because these emotions are temporary, they are difficult to recall accurately. Therefore, most studies have focused on the influence of a single factor (such as lighting, music, or color) on hotel restaurant atmosphere, whereas few have discussed the influence of atmosphere and service performance on the customers’ sense of well-being. Therefore, this study focuses on whether a customer’s sense of well-being and their repurchase intention are influenced by an afternoon tea restaurant’s atmosphere and service performance. To improve customer experiences, reputable hotels and restaurants worldwide implement sensory experience strategies and attempt to create a pleasant atmosphere with music. An afternoon tea restaurant’s atmosphere influences the customer experience. Specifically, a favorable restaurant atmosphere can create an active and agreeable experience for customers. Therefore, this paper first addresses how an afternoon tea restaurant’s atmosphere influences customers’ sense of well-being.

Well-being is a subjective feeling of great satisfaction experienced by customers. Nickson et al. [

4] argued that customers feel satisfaction and pleasure from an excellent service experience. Jang and Namkung [

5] argued that service performance positively influences customer emotions. Godbey [

6] believed that having afternoon tea is a crucial part of a person’s leisure time and considerably strengthens people’s sense of well-being. Having afternoon tea is a popular leisure activity in modern society. Customer satisfaction and emotions are influenced by the performance of service personnel. Therefore, this paper raises the second question of how the service performance of a hotel restaurant’s personnel influences customers’ sense of well-being.

Unlike merely serving food, the act of providing afternoon tea entails immersing the customer in the experience by stimulating all five senses and providing an enjoyable and comprehensive period of time [

7]. Borucki and Burke [

8] believed that excellent service performance produces high satisfaction among and elicits positive comments from customers, thereby increasing the likelihood of a customer’s future visits. Kotler [

9] argued that customers develop a repurchase intention if they are satisfied with the goods or services they purchase. Afternoon tea is a major business offering in many Taiwanese five-star hotels. The largest group of consumers of afternoon tea is adult women aged 20 to 35 [

10]. Afternoon tea is an excellent diversion that relaxes both the body and mind. The persistent appeal to customers involves not only delicious food but also a warm and comfortable environment. Customers’ emotions and experiences influence their subsequent behavior. Therefore, this paper investigates how customers’ sense of well-being acquired in a hotel restaurant influences their repurchase intention.

5. Discussion

In terms of afternoon tea restaurant atmosphere, customers gave the highest scores to the following four items: (1) colors that create a warm atmosphere, (2) lighting that creates a comfortable atmosphere, (3) an enticing aroma, and (4) lighting that creates a warm atmosphere. Therefore, customers believe that color design, color hues, and lighting design influence the atmosphere. By contrast, customers provided low scores to the following three items: (1) exquisite three-tiered stands used to arrange desserts, (2) candles that create a warm atmosphere, and (3) a seating arrangement that creates a crowded feeling. This may have been due to differences in decorations, platter arrangements, table positions, and distances between tables among the five-star hotels. As shown in

Table 1, 70.1% of respondents felt that the three-tiered stand layout was enticing.

The restaurant atmosphere perceptions by customers also varied by sex. Specifically, significant differences emerged in the following items: (1) welcoming lighting, (2) a layout easy to move about in, (3) decorations or accessories to improve the aroma in the washroom, and (4) attractive paintings and pictures. Evidently, feelings toward aroma and decorations varied by customer sex. Customer age significantly influenced perceptions of the following items: (1) the paintings and pictures are attractive, (2) the furniture (e.g., dining tables or chairs) is high quality, (3) the background music relaxes me, (4) candles create a warm atmosphere, (5) the tableware (e.g., glass, china, and silverware) is high quality, (6) the linens (e.g., tablecloths and napkins) are attractive, (7) the seats are comfortable, and (8) the seating arrangement makes me feel crowded. Perhaps older customers who typically have high incomes have high requirements for the quality and layout of items. According to the research results, customer experiences, satisfaction, and enjoyment were influenced by an afternoon tea restaurant’s atmosphere, chiefly lighting, facility aesthetics, and table settings. The music played in a hotel is a factor that attracts customers to the hotel restaurant. Facility aesthetics may include paintings, pictures, plants, flowers, colors, and wall decorations.

For well-being, customers provided the highest scores on the following three items (arranged in descending order): (1) I am satisfied with my life, (2) I feel happy, and (3) when I engage in this activity, I feel fulfilled. Customers believe that having afternoon tea in a hotel contributes to a relaxing and enjoyable life and makes them feel happy. The following three items received low scores: (1) when I engage in this activity, I feel more satisfied than I do when engaging in most other activities, (2) when I engage in this activity, I feel happier than I do when engaging in most other activities, and (3) if I have not had afternoon tea recently, I feel unhappy. This is because afternoon tea is a static activity that is restricted to the amount of free time people have. According to the research results, customers believe that they can acquire a sense of well-being (e.g., relaxation, enjoyment, and pleasure) by having afternoon tea in a hotel.

For service performance, customers provided the highest scores to the following three items (arranged in descending order): (1) employees are neat and well dressed, (2) employees are friendly and helpful to customers, and (3) employees can help customers when required. Evidently, the service personnel of hotel restaurants effectively provided timely and high-quality service to customers. The following three items regarding service personnel received low scores: (1) asking suitable questions and listening to learn customers’ wants, (2) suggesting items customers might enjoy but did not think of, and (3) identifying and relating item features to meet a customer’s needs. Evidently, the service personnel of hotel restaurants have room to improve their service. For example, to offer more considerate services, service personnel can use details to identify services that customers may want and proactively ask them what they want. According to the research results, the service performance of personnel is a crucial factor that influences customer feelings and selection of hostel restaurants. Therefore, hotel managers should encourage service personnel to provide considerate and proactive services to help customers to feel comfortable.

For repurchase intention, customers provided the highest scores on the following three items (arranged in descending order): (1) I would like to return to this restaurant in the future, (2) I would recommend this restaurant to my friends, and (3) I am willing to remain at this restaurant for longer than I had planned. Therefore, customers are willing to return to the restaurant they visited to enjoy afternoon tea, recommend the restaurant to their relatives and friends, and remain for longer than scheduled. Low scores were provided on the following item: I am willing to spend more money than I had planned at this restaurant. This is because afternoon tea in a five-star hotel’s restaurant is expensive. In

Table 1, “Recommendation by relatives and friends” accounts for 36.6% of the responses to “Which type of publicity primarily attracted you to afternoon tea?” This is consistent with the high scores for the item “I would recommend this restaurant to my friends.” Therefore, receiving WOM recommendations from relatives and friends is the major factor that attracts customers to afternoon tea. Customers who feel a sense of pleasure, relaxation, and satisfaction have higher repurchase intentions. According to the aforementioned research results, the sense of well-being felt by customers in a hotel restaurant increases their repurchase intention.

A high sense of well-being creates a strong repurchase intention and high willingness to recommend afternoon tea to relatives or friends. To increase customers’ repurchase intentions, hotel managers should attempt to satisfy customers’ needs by improving facility aesthetics and service performance. According to the regression analysis results, service performance increases the sense of well-being more than restaurant atmosphere does. The research objects of this present study were five-star hotels, which are all considered upscale. Therefore, the difference in atmosphere between such hotels is slight. Modern customers are sensitive to services, and restaurants typically distribute customer satisfaction questionnaires to collect customer comments regarding service performance. Because the characteristics of service personnel typically vary between hotel restaurants, the service performance perceived by customers typically differs.

The survey of customers’ afternoon tea habits indicated that customers had frequently visited nonhotel afternoon tea restaurants (five to six times on average) in the past year. This may be due to the high standard of consumption in hotel restaurants. However, high-income or older customers had frequently visited hotel restaurants in the past year. On average, customers spend 90 to 120 min in both hotel and nonhotel afternoon tea restaurants. In addition, customers are attracted to the three-tiered stand layout and enjoy miniature cakes. Therefore, this study recommends that afternoon tea restaurants offer various miniature cakes and arrange desserts on three-tiered stands. In the present study, most afternoon tea consumers were students and young women. In addition, afternoon tea (including English and Taiwanese styles) is the most popular among people aged 20–30, which would appear to indicate afternoon tea has gained in popularity. In summary, most afternoon tea consumers who want to relieve stress and chat with friends are students and young women rather than middle-aged people.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Hospitality is a valuable tool for economic diversification, and hospitality development can be an effective means of engaging communities by providing new markets for agricultural products [

49]. From the Victorian era to the present, afternoon tea consumers have been mostly women, but male afternoon tea consumers are increasing in number. In the present study, the qualities of an afternoon tea restaurant’s atmosphere perceived by customers increased customers’ sense of well-being. Specifically, lighting and facility aesthetics most significantly influenced well-being, followed by table settings and ambience, whereas layout influenced well-being the least. In addition, the service performance of hotel restaurant personnel perceived by customers influenced customer well-being, and the influence of service performance was more significant than that of restaurant atmosphere. Finally, customers’ sense of well-being significantly influenced their repurchase intention. To increase customers’ repurchase intention, afternoon tea restaurants in hotels should be designed to offer a distinctive atmosphere (e.g., making full use of lighting effects, playing different styles of music, and displaying distinctive ornaments, flowers, and drawings) to provide a sense of relaxation and enjoyment. In addition, service personnel should be trained in professional competencies and skills.

The Internet and mass media are vital for marketing because young consumer groups tend to search for hotel restaurants on the Internet. In addition, consumers may be attracted by promotions on official websites or by point-accumulating events. Compared with Internet media, WOM communication between relatives and friends is more attractive to potential consumers. Uniquely shaped three-tiered stands can create an atmosphere of elegance and romance to attract potential consumers. The findings concerning customers’ afternoon tea habits (

Table 2) indicated that customers visit nonhotel afternoon tea restaurants frequently because the standard of consumption in hotel restaurants is high. Nevertheless, consumers are willing to have afternoon tea in hotel restaurants if they can feel a sense of well-being (e.g., a sense of enjoyment or relaxation). Compared with nonhotel afternoon tea restaurants, hotel restaurants have advantages with respect to their exquisite desserts, overall hotel decor, tableware settings, and professional service performance. The most successful publicity method to increase customers’ repurchase intention and willingness to recommend hotel restaurants to others is to make them feel comfortable, acquire a sense of well-being, and experience unique value beyond money.

The well-known M-R model is used to explain the effects of physical environments on customer behavior [

16]. Many studies have focused on a single dimension of atmosphere, but few have discussed the influence of an afternoon tea restaurant’s overall atmosphere. In addition, most studies on well-being have focused on work environments or leisure tourism, whereas few have discussed well-being in the hospitality industry. This paper discussed the influence of overall atmosphere on well-being to provide a valuable reference for subsequent studies. This study investigated the influence of afternoon tea restaurant atmosphere on the sense of well-being. Because well-being is an abstract concept, it cannot be measured accurately by using various original measuring scales. By referencing the subjective well-being scale [

45], well-being scale [

46], and Oxford happiness inventory [

47], questionnaire items on well-being suited to the present study were selected, and a few other question items were added, resulting in a total of 10 question items. Cronbach’s α values of the question items of well-being equaled 0.900, indicating high reliability. Based on factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.884, indicating a strong relationship between variables. Therefore, the scale used herein could measure the sense of well-being felt by afternoon tea consumers. Since 2013, the atmosphere of upscale or themed restaurants has been discussed frequently. This study focused on five-star hotels to address the deficiency in empirical studies on this topic in the hospitality industry.

In addition, this paper offers suggestions on restaurant layout, design, atmosphere, food and desserts, employee training, and marketing strategy. Regarding restaurant atmosphere, unique colors or ornaments can be used to create a romantic or fashionable atmosphere. In particular, large glass panes that allow customers to view outdoor landscapes are suggested. Bright lighting and magnificent crystal lamps can create a unique atmosphere. In addition, fresh flowers and candles can be arranged to create a romantic atmosphere. Elegant music can make customers feel relaxed, and live piano performances can increase the romantic atmosphere. Aroma is crucial to restaurant atmosphere. In particular, customers readily perceive the cleanliness, aroma, and decorations of washrooms. Health and environmental sustainability concerns have grown among consumers and affect their food consumption selections [

50]. The flavor of food and desserts is the most crucial factor attracting people to afternoon tea restaurants. Thus, hotels can offer themed or uniquely shaped desserts. The survey indicated that male and elderly customers prefer English-style desserts such as scones and sandwiches. Hotels that provide afternoon tea menus can offer more savory foods, desserts, and healthy snacks to satisfy diverse customer demands.

Although the original M-R model offers rich insights for managerial practices, studies have ignored service personnel misbehavior. The importance of positive emotions indicates that customers should experience pleasant sensations in restaurants [

51]. Service personnel should be trained to provide considerate service and proactively satisfy customers’ needs to make a positive impression and increase their repurchase intention. Regarding marketing, inspiring recommendations from relatives and friends is the preferred method of attracting people of different ages to hotel restaurants. Because the Internet is highly developed, an increasing number of consumers select hotel restaurants online or by viewing bloggers’ comments and shares. In addition, frequent guest programs, coupons, and credit card discounts can attract customers to hotel restaurants. Therefore, hotel restaurants should use various promotions and events at appropriate times (e.g., birthday discounts, themed events, and holiday events).

Numerous limitations are associated with this study. First, because the M-R environmental psychology model processes only potential indicators and dimensions, individual observations may lose meaning. In this study, the M-R model focused only on atmosphere and service qualities that affect well-being. Thus, improved linkage between theoretical frameworks and practical management and marketing topics can be further examined to benefit hotel managers. Second, this study focused only on five-star hotels in Taipei. Because afternoon tea is gradually growing in popularity, more restaurants and coffee houses are providing unique afternoon tea services and products. Studies regarding guest values and loyalty are warranted to add insights to hospitality product development and quality improvement.