The Role of Networks in Improving International Performance and Competitiveness: Perspective View of Open Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

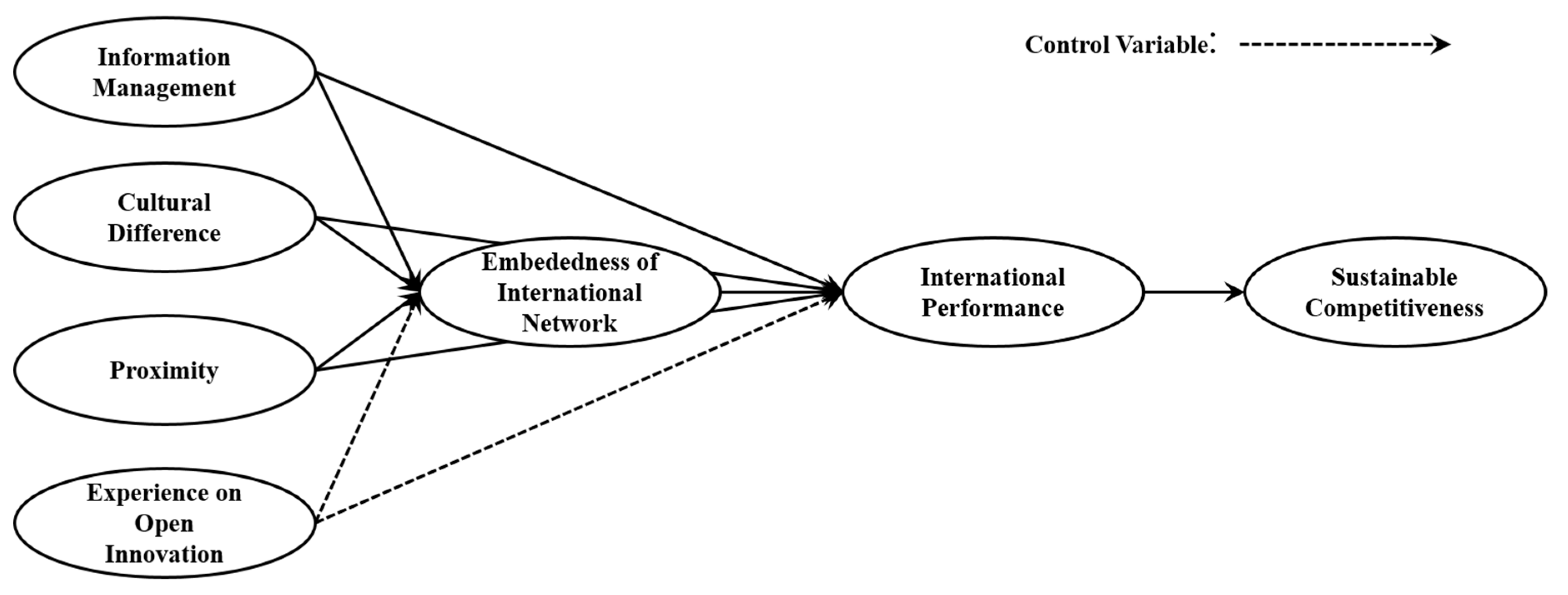

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Network Formation Principles

2.2. Determinants of International Network Embeddedness

2.3. International Network Embeddedness and International Performance

2.4. International Performance and Competitiveness

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.3. Analytical Method and Bias

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement and Structural Model Results

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Information Management | - Our organization can collect international market information effectively. - Our organization can collect useful information about successful internationalization. - Our organization shares and communicates information with our potential international partners effectively and positively. - Our organization utilizes useful information about successful internationalization | Ritter et al. [20], Sharmo and Blomstermo [50], Julien and Ramangalahy [44] |

| Cultural Difference | - It is difficult to harmonize with potential international partners. - It is difficult to work out constructive solutions due to cultural differences when there is conflict. - It is difficult to understand potential international partners’ behaviors when they have different cultural backgrounds. - Our organization is not friendly when dealing with potential international partners with different cultural backgrounds. | Ritter et al. [20], Sharmo and Blomstermo [50], Julien and Ramangalahy [44] |

| Proximity | - Our organization feels that there is a smaller physical distance between potential international partners and it. - Our organization feels that there is a smaller psychological distance between potential international partners and it. - Our organization thinks that proximity plays an important role in forming and embedding a network with potential international partners. | Wilkinson [4], Ritter et al. [20] |

| International Network Embeddedness | - Our organization forms strong and close relationships with potential international partners. - Our organization has strong and close relationships with international partners. - Our organization communicates with international partners frequently. - Our organization coordinates activities to form strong and close relationships with potential international partners effectively and positively. - An international network between our organization and international partners is well embedded. - Our international partners trust us. | Andersson [54], Ritter et al. [20] |

| International Performance | - Export sales have been improving. - The number of international markets has been increasing. - International assets have been improving. - The number of international branches has been increasing. | Bloodgood [70], Kuivalainen [71] |

| Competitiveness | - The overall competitiveness of our organization has been improving. - Our organization has higher competitiveness than our competitors. - Our organization has higher service quality than our competitors. - Service quality and competitiveness have been improving. - Organizational capabilities have been improving. | Cox and Blake [72], Perez and de Pablos [73] |

References

- Acs, Z.J.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Audretsch, D.B.; Carlsson, B. A knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, G.; Malecki, E.J. Networking for competitiveness. Small Bus. Econ. 2004, 23, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M.; McDougall, P.P. Defining International entrepreneurship and modelling the speed of internationalization. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, I.F. A history of channels and network thinking in marketing in the twentieth century. Australas. Mark. J. 2001, 9, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monferrer, D.; Blesa, A.; Ripollés, M.; Kuster, I.; Vila, N. Effect of network market orientation on new venture’s international performance. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2013, 5, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbetokum, A.; Oluwadare, A.J.; Ajao, F.; Jegede, O.O. Innovation systems research: An agenda for developing countries. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M.K.; D’Souza, D.E. Venturing into foreign markets: The case of the small service firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 17, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, L.A.; Gillespie, K. Information sources for new ventures in the Turkish clothing export industry. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 20, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Renko, H.; Autio, E. The network embeddedness of new, technology-based firms: Developing a systemic evolution model. Small Bus. Econ. 1998, 11, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.N.; Danis, W.M. Social networks and speed of new venture internationalization during institutional transition: A conceptual model. J. Int. Entrep. 2010, 8, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.P.; Shane, S.; Oviatt, B.M. Explaining the formation of international new ventures the limits of theories from international-business research. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, N.E. The network dynamics of international new ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, E.M.; Kahler, M.; Montgomery, A.H. Network analysis for international relations. Int. Organ. 2009, 63, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-B.; Ronto, S.E. Business performance, process innovation and business partnership in the global supply chain of Korean manufacturers. J. Korea Trade 2010, 14, 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Brashears, M. Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Lavie, D.; Madhavan, R. How do networks matter? The performance effects of interorganizational networks. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Villar-López, A. Effect of SMEs’ international experience on foreign intensity and economic performance: The mediating role of internationally exploitable assets and competitive strategy. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 116–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in inter-firm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Quart. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.W. Determinants of network in cooperation between local governance: The relationships between determinants of network of local governance and centricity. Korean J. Local Gov. Stud. 2013, 17, 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, T.; Wilkinson, I.F.; Johnston, W.J. Measuring network competence: Some international evidence. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2002, 17, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Lee, I.W.; Feiock, R. Internationalization collaboration networks in economic development policy: An exponential random graph model analysis. Policy Stud. J. 2012, 40, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Cho, D.-S.; Kwon, K.-H. Subsidiary’s external networkability as a source of competitive advantage. J. Korea Trade 2007, 11, 107–139. [Google Scholar]

- Feiock, R.C.; Scholz, J.T. Self-Organizing Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, M.; Schroeter, A. Why does the effect of new business formation differ across regions? Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 36, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, J.T.; Lin, N.P.; Li, H.C. The effects of network embeddedness on service innovation performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1723–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P.; Romano, P.; Formentini, M. The impact of supply chain integration on responsiveness: The moderating effect of using an international supplier network. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 49, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.A. Ground-Up “Quaternary” innovation strategy for South Korea using entrepreneurial ecosystem platforms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R. Network location and learning: The influence of network resources and firm capabilities on alliance formation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 30, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The influence of relationship strength among business partners on performance in international strategic alliances. Korean J. Econ. Manag. 2004, 33, 273–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, M.T.; Soderstrom, S.B.; Uzzi, B. Dynamics of dyads in social networks: Assortative, relational and proximity mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.; King, C., III; Juda, A.I. Small worlds and regional innovation. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Bhatt, M.; Adolphs, P.; Trane, D.; Camerer, C.F. Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making. Science 2005, 310, 1680–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, R.; Nohria, N.; Zaheer, A. Strategic networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S. Technology convergence, open innovation, and dynamic economy. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.A.; Phelps, C.C. Inter firm collaboration networks: The impact of large-scale network structure on firm innovation. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B.; Spiro, J. Collaboration and creativity: The small world problem. Am. J. Sociol. 2005, 111, 447–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.J. Network, dynamics, and the small-world phenomenon. Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 105, 493–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J.; Levy, M. Distance is not dead: Social interaction and geographical distance in the internet era. Comput. Sci. 2009, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H.J.; Kim, P.; Bea, I.G. Determinants of supply chain partnership and performance. E Bus. Res. 2009, 10, 363–364. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.G.; Hang, S.W.; Jo, C.H. Information systems and its performance in container yard operation companies. Int. Commer. Manag. 2009, 24, 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, D.; Wellman, B.; Carrasco, J. Does distance matter in the age of the Internet? Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2747–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, P.A.; Ramangalahy, C. Competitive strategy and performance of exporting SMEs: An empirical investigation of the impact of their export information search and competencies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J.; Hsieh, L.H. Decision mode, information and network attachment in the internationalization of SMEs: A configurational and contingency analysis. J. World Bus. 2014, 49, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.S.; Mueller, S.L. A case for comparative entrepreneurship: Assessing the relevance of culture. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, K.; Mather, R.; Dalrymple, R. Culture, role and group work: A social network analysis perspective on an online collaborative course. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 45, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Altinay, L. Social embeddedness, entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth in ethnic minority small businesses in the UK. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 30, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.G. Difference of culture between business partners in international joint investment: The effect of governing structures on performance. J. Int. Manag. 2004, 8, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.D.; Blomstermo, A. The internationalization process of born globals: A network view. Int. Bus. Rev. 2003, 12, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.-K.; Lim, J.-S.; Lee, H.-Y. A model for the mechanism of container ports’ cooperation networks in Northeast Asia. J. Korea Trade 2007, 11, 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Musteen, M.; Francis, J.; Datta, D.K. The influence of international networks on internationalization speed and performance: A study of Czech SMEs. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, F.; Gabrielsson, M. Network development and firm growth: A resource-based study of B2B Born Globals. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Forsgren, M.; Holm, U. The strategic impact of external networks: Subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corporation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwani, M.U.; Narayandas, N. Long-term manufacturer-supplier relationships: Do they pay off for supplier firms? J. Mark. 1995, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schijndel, L.V. TCKF-Connect: A Cross-Disciplinary Conceptual Framework to Investigate Internationalization within the Context of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Kim, D. Empirical relationships among technological characteristics, global Orientation, and internationalisation of South Korean new ventures. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, D.S. Impacts of metacognition on innovative behaviors: Focus on the mediating effects of entrepreneurship. J. Open Innov. Technol. Soc. Complex. 2018, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G. Strategic business and network positioning for internationalization. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P. Impacts of network relationships on absorptive capacity in the context of innovation. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 30, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, W.; Glyn, A.; Van Reenen, J. Export market performance of OECD Countries: An empirical examination of the role of cost competitiveness. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 128–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S. Competitiveness indices and developing countries: An economic evaluation of the global competitiveness report. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1501–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momaya, K.; Selby, K. International competitiveness of the Canadian construction industry: A comparison with Japan and the United States. Can. J. Civil Eng. 1998, 25, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethier, J.J.; Hirn, M.; Straub, S. Explaining enterprise performance in developing countries with business climate survey data. World Bank Res. Obs. 2010, 26, 258–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixanet, J. Export promotion programs: Their impact on companies’ internationalization performance and competitiveness. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummela, N.; Saarenketo, S.; Puumalainen, K. Global mind set—A prerequisite for successful internationalization? Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2004, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Mothakunnel, A.; de Vel-Palumbo, M.; Ames, D.; Ellis, K.A.; Reppermund, S.; Sachdev, P.S. Influence of population versus convenience sampling on sample characteristics in studies of cognitive aging. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplowitz, M.C.; Hadlock, T.D.; Levine, R. A comparison of web and mail survey response rates. Public Opin. Quart. 2004, 68, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodgood, J.M. Venture adolescence: Internationalization and performance implications of maturation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2006, 12, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivalainen, O.; Sundqvist, S.; Servais, P. Firms’ degree of born-globalness, international entrepreneurial orientation and export performance. J. World Bus. 2007, 42, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.; Blake, S. Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. Executive 1991, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.R.; de Pablos, P.O. Knowledge management and organizational competitiveness: A framework for human capital analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2003, 7, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, G.; Yoon, B.; Park, J. Open innovation in SMEs—An intermediated network model. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Baumgartner, H. The evaluation of structural equation models and hypothesis testing. In Principles of Marketing Research; Bagozzi, R., Ed.; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 386–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL V: Analysis of Linear Structural Relationships by Maximum Likelihood and Least Squares Methods; University of Uppsala: Uppsala, Sweden, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.C. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.R.; Brett, J.M. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontis, N.; Booker, L.D.; Serenko, A. The mediating effect of organizational reputation on customer loyalty and service recommendation in the banking industry. Manag. Decis. 2007, 45, 1426–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolle, D.; Soroka, S.; Johnston, R. When does diversity erode trust? Neighborhood diversity, interpersonal trust and the mediating effect of social interactions. Political Stud. 2008, 56, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, D.; Lawson, C.; Moore, B.; Wilkinson, F. Collective learning processes, networking and ‘institutional thickness’ in the Cambridge region. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echols, A.; Tsai, W. Niche and performance: The moderating role of network embeddedness. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 248 | 69.7 |

| Female | 108 | 30.3 |

| Position | ||

| CEO | 184 | 51.7 |

| Director | 116 | 32.6 |

| Senior Manager | 56 | 15.7 |

| Number of Employees | ||

| 1−49 | 234 | 64.9 |

| 50−99 | 63 | 17.7 |

| 100−149 | 25 | 7.0 |

| 150−199 | 35 | 9.8 |

| 200−299 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Duration of Export Activity | ||

| 1−3 years | 100 | 28.1 |

| 3−5 years | 50 | 14.0 |

| 5−7 years | 78 | 21.9 |

| 7−9 years | 85 | 23.9 |

| More than 9 years | 43 | 12.1 |

| Scale | Mean | Standard Deviation | Cross-Construct Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |||

| (1) | 2.7781 | 1.39362 | 1 | ||||||

| (2) | 2.5716 | 1.06965 | 0.176 ** | 1 | |||||

| (3) | 2.7331 | 0.93187 | −0.078 | −0.288 ** | 1 | ||||

| (4) | 2.7200 | 0.87208 | 0.041 | 0.529 ** | −0.362 ** | 1 | |||

| (5) | 2.8240 | 0.89455 | 0.209 ** | 0.548 ** | −0.460 ** | 0.591 ** | 1 | ||

| (6) | 2.5632 | 0.98789 | 0.280 ** | 0.614 ** | −0.237 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.411 ** | 1 | |

| (7) | 2.5035 | 0.98946 | 0.254 ** | 0.297 ** | −0.323 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.319 ** | 1 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.910 | 0.818 | 0.837 | 0.948 | 0.937 | 0.923 | |||

| Construct Reliability | 0.868 | 0.956 | 0.851 | 0.944 | 0.933 | 0.958 | |||

| AVE | 0.625 | 0.844 | 0.658 | 0.737 | 0.778 | 0.822 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit statistics | χ2 = 909.475 (df = 283), χ2/df = 3.214, RMR = 0.074, NFI = 0.906, CFI = 0.931, TLI = 0.913, IFI = 0.916, RMSEA = 0.084 | ||||||||

| Path | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Error (S.E.) | C.R | p-Value | S. E | C.R | p-Value | S.E | C.R | p -Value | |

| Direct and Indirect Effects | |||||||||

| Experience on open innovation → International Performance | 0.092 | 2.676 | 0.007 | 0.080 | 2.459 | 0.014 | |||

| Information Management → International Performance | 0.487 | 8.572 | 0.000 | 0.282 | 5.163 | 0.000 | |||

| Cultural Difference → International Performance | −0.064 | −1.285 | 0.199 | −0.131 | −1.531 | 0.126 | |||

| Proximity → International Performance | 0.244 | 3.580 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 1.948 | 0.051 | |||

| Experience on open innovation → International Network | 0.085 | 5.809 | 0.000 | 0.128 | 3.450 | 0.000 | |||

| Information Management → International Network | 0.352 | 9.411 | 0.000 | 0.630 | 10.010 | 0.000 | |||

| Cultural Difference → International Network | −0.167 | −5.486 | 0.000 | −0.098 | 1.849 | 0.064 | |||

| Proximity → International Network | 0.221 | 5.660 | 0.000 | 0.285 | 4.261 | 0.000 | |||

| Experience on open innovation → International Network → International Performance | 0.048 | 0.025 | |||||||

| Information Management → International Network → International Performance | 0.224 | 0.018 | |||||||

| Cultural Difference → International Network → International Performance | −0.020 | 0.359 | |||||||

| Proximity → International Network → International Performance | 0.079 | 0.025 | |||||||

| International Performance → Competitiveness | 0.341 | 6.372 | 0.000 | 0.311 | 5.778 | 0.000 | 0.350 | 6.231 | 0.000 |

| International Network → International Performance | 0.948 | 9.658 | 0.000 | 0.320 | 6.352 | 0.000 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit statistics | χ2 = 793.063 (df = 179), χ2/df = 4.431 RMR = 0.110, NFI = 0.902, CFI = 0.921, TLI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.103, IFI = 0.921 | χ2 = 1153.632 (df = 313), χ2/df = 3.686 RMR = 0.121, NFI = 0.898, CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.896, RMSEA = 0.094, IFI = 0.917 | χ2 = 985.100 (df = 309), χ2/df = 3.188 RMR = 0.074, NFI = 0.914, CFI = 0.936, TLI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.078, IFI = 0.937 | ||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, J.; Sung, S.; Ryu, D. The Role of Networks in Improving International Performance and Competitiveness: Perspective View of Open Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031269

Yoon J, Sung S, Ryu D. The Role of Networks in Improving International Performance and Competitiveness: Perspective View of Open Innovation. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031269

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Junghyun, Sanghyun Sung, and Dongwoo Ryu. 2020. "The Role of Networks in Improving International Performance and Competitiveness: Perspective View of Open Innovation" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031269

APA StyleYoon, J., Sung, S., & Ryu, D. (2020). The Role of Networks in Improving International Performance and Competitiveness: Perspective View of Open Innovation. Sustainability, 12(3), 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031269