Abstract

Our paper examines the potential effect of different types of entrepreneurship (in particular, early-stage entrepreneurship, opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, and necessity-driven entrepreneurship) on economic growth at a national level and aims to identify whether the contribution of entrepreneurship to economic growth differs according to the stage of economic development of a country. Our empirical analysis is based on the panel data, which covers 17 years (2002–2018) and 22 European countries, classified into two groups. The results suggest that all three types of entrepreneurship have a greater impact on economic growth for the entire sample of European countries, and some types of entrepreneurship are more important than others. We find that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and early-stage entrepreneurship would be key factors in stimulating economic growth across the sample of European countries. Our estimations also show that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship would have a greater impact in transition countries, while necessity-driven entrepreneurship would have a stronger influence in the innovation-driven countries. The results of our research could be of interest to policymakers, as it can help in identifying and implementing the most appropriate measures to eliminate the obstacles in the macroeconomic environment that entrepreneurs face, and measures to support innovative entrepreneurial activities.

1. Introduction

One of the fundamental problems of any national and regional economy is to determine the drivers of economic growth and development. Neoclassical studies of economic growth have highlighted investments in physical capital and labor as the main factors related to economic growth [1,2], while the endogenous growth theory [3] adds the factor of knowledge. Compared to traditional factors of production (capital and labor), knowledge would have a substantial impact on economic growth due to its propagation to be used by third parties’ enterprises [4,5]. Subsequently, the researchers included in the neo-classical model other factors that drive economic growth, including entrepreneurship.

The significant effects of the recent international crisis on national economies have brought to the attention of researchers and policymakers the problem of the factors that determine the economic growth. Given the severe economic downturn in some countries, including European countries, and the high unemployment rate, especially among young people, their orientation towards entrepreneurship, which is considered an engine for economic growth, is crucial.

Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs are considered as important drivers of economic growth because they contribute to the creation of new jobs, new employment opportunities, the emergence of new innovations, but also to the stimulation of competition and competitiveness.

Several researchers (such as [4,6,7,8,9,10]) argue that entrepreneurship can make a significant contribution to the economic growth by serving as a means for introducing innovations, knowledge spillovers, increasing competition, and increasing the variety of businesses.

The contribution of entrepreneurship to economic growth and to the development of an economy is widely discussed and accepted [4,5,6,7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. However, empirical studies indicate mixed results regarding the role of entrepreneurship in economic growth due to the variety of types of entrepreneurship, but also to the characteristics of the macroeconomic environment in which economic growth occurs [14]. In this context, the objective of our research is to examine the effects of different types of entrepreneurship on economic growth at a national level (expressed as per capita (Gross Domestic Product-GDP)) and to identify whether the contribution of entrepreneurship to economic growth differs depending on the stage of economic development of a country. Our empirical analysis is based on the panel data, which covers the period 2002–2018 and 22 European countries (Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom), which were selected according to the availability of data regarding, in particular, entrepreneurship.

The study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship and economic growth in two ways. First, we offer new insights on the impact of different forms of entrepreneurship on economic growth. Secondly, our research focuses on a sample of European countries, classified into two groups, according to their stage of economic development, and examines how the effect of entrepreneurship on economic growth differs depending on the stage of economic development of a country. Our paper brings, as a novelty, the analysis of the nexus between the motivations of entrepreneurship and the economic growth for an extended sample of countries and for an extended period. Previous studies have considered only a small number of countries. Another novelty of our paper comes from including in the analysis the motivation of the entrepreneurs. Additionally, grouping the countries according to their level of development facilitates the realization of a comparative analysis and identification of customized solutions for each type of economy.

The content of this paper is structured as follows: section two briefly reviews the literature on entrepreneurship and economic growth, with special emphasis on empirical papers; section three presents the data, the variables, and the methodology; section four discusses the main findings of our empirical study; the final section presents our concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review on Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth

The analysis of the literature reflects the existence of a large number of studies, which focused on examining the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth such as: [4,5,9,11,12,13,15,19,24,25,26,27,28]. Some authors [8,13,24,26], considering the stage of economic development of a country, have found that the relationship between entrepreneurship (business ownership) and the gross domestic product per capita may be U-shaped.

Some studies [9,11] have emphasized that entrepreneurship is an important determinant of economic growth, but it was omitted from the neoclassical model of growth, which linked labor and capital to the output. These authors argued for the positive impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth and development by the concept of entrepreneurship capital and supported its inclusion in economic growth models. Thus, using data for German regions, Audretsch and Keilbach [11] examined the link between different forms of entrepreneurship capital (the number of start-ups relative to population, start-up activity in high-technology manufacturing industries, start-up activity in the Information and communications technology ICT industries) and economic growth. The empirical results indicate that entrepreneurship capital is positive and significantly linked to economic performance. The authors define entrepreneurship capital as the totality of factors that influence and shape the economic environment so that it facilitates the start-up of new businesses. Based on their research, the authors emphasize that public policing, which seeks to promote entrepreneurship capital, should have a positive impact on economic performance.

The intensification of debates within the academic community and policymakers on identifying the factors that promote the economic growth of a country or region has led more researchers to focus on entrepreneurship and, in particular, to investigate its effect on economic growth. Thus, Acs et al. [4] empirically tested the extent to which entrepreneurship contributes to promoting economic growth. The results of the study show that in addition to investments in research and human capital, entrepreneurship has a positive impact on economic growth. Similarly, Hessels and Van Stel [16] examined the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth, taking into account the export orientation of new firms. The authors found a positive impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth, but also that export orientation can have an important supplementary contribution to economic growth. Using data for 18 countries, Acs et al. [5] empirically test and analyze the importance of entrepreneurship (measured by the self-employment rate) in economic growth. The results of the study indicate that knowledge-based entrepreneurship contributes significantly to promoting economic growth. The authors point out that entrepreneurship is a mechanism that facilitates the spillover of knowledge, thus contributing to economic growth.

The relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth was also analyzed by Galindo and Méndez [17], who points out that there is a close connection between entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic growth, entrepreneurship and innovation would contribute to the increase of economic activity, and the latter would promote entrepreneurship and innovative activities. In their study, the authors identified a virtuous cycle between innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic growth, in which each of the three factors would have positive effects on the others.

A more recent study [20] highlights the link between entrepreneurship and economic growth through the quality of the institutional environment. Using data for 25 European Union countries, for the period 2003–2014, the authors found that the quality of institutions stimulates (productive) entrepreneurship, which, in turn, would contribute to economic growth. The mentioned research concludes that entrepreneurship positively affects economic growth, and the most important predictors of entrepreneurship would be financial stability, the size of government, and the perceived skills to start a business.

Although the contribution of entrepreneurship to achieving economic growth is widely recognized, some studies show that there are different types of entrepreneurship that do not have the same effect on economic growth. For example, using data for 37 countries, Wong et al. [12] examined the impact of technological innovation and of different types of entrepreneurial activities on GDP growth. The results of the study show that innovation is a positive and significant determinant of GDP growth. With regards to entrepreneurship, the authors find that high-potential entrepreneurial activity influences GDP growth more strongly than other types of entrepreneurial activity. Mueller [10] tested the West German regions for whether increased entrepreneurship contributes to regional economic growth. Empirical results showed that an increase in the activity of innovative start-ups contributes more to economic growth than to an increase in entrepreneurship in general. The author also points out that only parts of the regional economic growth are stimulated by entrepreneurship, because it is mainly driven by research and development activities in existing firms, investments in physical capital stocks, and human capital. Additionally, other researches show that the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth is different depending on the stage of economic development of a country, but the empirical results are quite heterogeneous. Thus, some authors [8,25,29] find that the effect of entrepreneurship on economic growth is positive or greater in developed countries compared to developing countries, while other authors [27] find that entrepreneurship has no significant impact in high-income countries, but has a significantly positive impact in low-income countries.

Of particular interest to our research are the studies that have focused on examining the effect of different forms of entrepreneurship on economic growth in countries with different levels of economic development. Thus, Van Stel et al. [25] examined how entrepreneurial activity influences Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth and found that entrepreneurship (measured by nascent entrepreneurs and owner/managers of young businesses) affects GDP growth differently, depending on the level of economic development of the countries. Thus, the results of the study indicate that the entrepreneurial activity rate has a negative effect in the case of poor countries and a positive effect in the case of rich countries. The authors argue that this difference between countries may be related to the lower human capital levels of entrepreneurs in poorer countries. Valliere and Peterson [15] highlight for a sample of 44 countries that entrepreneurship is an important predictor of economic growth in both developed and emerging countries, but its contribution to economic growth is different depending on the types of entrepreneurial activity and the level of economic development of countries. The authors found a positive and significant relationship between high expectation entrepreneurship and economic growth in developed countries but not in emerging countries. Based on a sample of 36 countries, Stam and Van Stel [14] analyzed whether the role of entrepreneurship in economic growth was different depending on the level of economic development of the countries. The authors found that in low income countries, entrepreneurship has no effect on economic growth, while in transition and high-income countries, both entrepreneurship in general and growth-oriented entrepreneurship seem to have a significant impact on economic growth. Minniti and Lévesque [30] argue that entrepreneurship is an important factor in the process of economic growth and find that higher economic growth can be recorded when the number of research-based or imitative entrepreneurs grows. A recent study [22] finds a negative effect of entrepreneurship (measured by established business ownership rate) on regional development of developing countries (expressed as gross domestic product per capita and gross national income), which may be due to the imperfection of public institutions in the respective countries.

Empirical evidence, which supports the argument that entrepreneurship plays a different role in economic growth in countries at different levels of economic development, is also provided by other recent studies, as follows. Urbano and Aparicio [19] empirically analyzed the effect of different types of entrepreneurship capital (overall total entrepreneurial activity (TEA), opportunity TEA, and necessity TEA) on economic growth in 43 countries (member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and non-member countries), for the period 2002-2012. The research results show that entrepreneurial activity is an important driver of economic growth in all countries included in the sample. The authors also find that the positive effect of overall TEA on economic growth is higher in OECD countries compared to non-OECD countries, and in the post-crisis period in all countries compared to the pre-crisis period. Lepojević et al. [18] showed the positive impact of entrepreneurial activity on economic growth, which, however, is higher in developed countries than in developing countries. Additionally, the authors argued that in developed countries, the greatest impact on economic growth (expressed by the GDP growth rate) is opportunity-based entrepreneurship, followed by high expectation entrepreneurship, while the least impact was made by necessity-based entrepreneurship. Comparatively, in developing countries, the highest impact on economic growth has high expectations entrepreneurship, followed by necessity-based entrepreneurship, and the lowest impact was made by opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Boudreaux [28] notes that in middle and high-income countries, opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship has a positive effect on economic growth, and in low-income countries, necessity-motivated entrepreneurship has a negative effect on economic growth. Using panel data for 55 developed and developing economies, from 2004-2011, Doran et al. [21] argued that the effect of different types of entrepreneurship on economic growth varies depending on the stage of economic development of a country. The authors find that entrepreneurial attitudes have a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita in high-income countries, while entrepreneurial activity has a negative impact on middle/low-income countries.

Other studies in the field point out the role of monetary policy but also of the risk and uncertainty about a country’s economy [31,32,33,34]. Increased levels of risk and uncertainty influence entrepreneurs but also their motivation, also generating effects at the macroeconomic level.

The studies analyzed in this part of the paper generally indicate a positive and significant effect of entrepreneurship on economic growth, but the results are not clear, especially regarding the effects of different types of entrepreneurship on economic growth in countries with different levels of development. On the other hand, the review of empirical studies indicates the existence of a small number of recent researches focused on European countries. Therefore, our study complements the literature in the field of entrepreneurship by providing empirical evidence on the effect of different forms of entrepreneurship on economic growth in European countries, which have different levels of economic development.

3. Data and Methodology

To analyze the contribution of different types of entrepreneurship to economic growth, we considered a sample of 22 European Union member countries, namely: Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. We chose the countries according to the availability of data for the variables considered in the analysis.

To ensure that we reached the main purpose of our paper, we have separated the countries into two categories based on their degree of economic development. Taking into account the classification made by Schwab and Sala-i-Martin [35], we have considered the level of GDP per capita as criterion. The values for the GDP per capita considered for the classification of countries are those considered in the global competitiveness report [31]: < $2000 US dollars for the factor-driven economies; between $2000 US dollars and $2999 US dollars for the economies in transition from stage 1 to stage 2; between $3000 US dollars and $8999 US dollars for the efficiency-driven economies; between $9000 US dollars and $17,000 US dollars for the economies in transition from stage 2 to stage 3; and > $17,000 US dollars for the innovation-driven economies. The global competitiveness report [36] describes the particularities of each category. All the countries included in our sample have values for the GDP per capita below $9000 US dollars, so therefore we will have only two groups of countries: in transition- and innovation-driven. The transition economies are those countries that are more competitive than those situated in the efficiency-drive stage. In these countries, the productivity must increase, the enterprises must develop more efficient production processes and increase product quality, in order to sustain the wages that are rising with advancing development. On the other hand, when the countries move to the innovation-driven stage, the wages are higher, the economies can sustain those higher wages, and the higher levels of standard of living only if the businesses can compete on the market through new, sophisticated, and innovative production processes. The classification of the 22 countries that we have considered in our analysis is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The classification of the 22 European countries according to their stage of development.

For each country we have considered a set of indicators measuring economic growth, the entrepreneurial activity, and the macroeconomic conditions.

The dependent variable in our study is GDP per capita, which represents one of the most important indicators of economic growth. Data on this indicator was obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database [38]. Our key explanatory variable is entrepreneurial activity at country level, measured by total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA), and within it, we operated separately with opportunity-driven early-stage entrepreneurship activity (OEA) and necessity-driven early-stage entrepreneurship activity (NEA), as suggested in other previous studies [12,15]. Data on the three entrepreneurial variables comes from the global entrepreneurship monitor [39], which is one of the most important sources of data on entrepreneurship. GEM data are collected in the adult population survey, for a sample of at least 2.000 respondents per country, and the basic survey questions are the same for each participating country, which ensures comparable measures that allow relevant cross-country analyses to be conducted.

The total early-stage entrepreneurial activity is one of the main indicators of the GEM and has a significant importance for the economy of a country because the entrepreneurs involved in this phase of entrepreneurial activity could contribute to the creation of new jobs and innovations, thus contributing to economic growth and development. According to GEM methodology, the TEA reflects the percentage of working age population that is actively involved in starting a new venture and/or managing a business less than 42 months old. Thus, the TEA includes nascent entrepreneurs and young business owners. These two types of entrepreneurs (called early-stage entrepreneurs) are engaged in new business activity.

Depending on the motivation of individuals to enter into entrepreneurship (opportunity vs. necessity), GEM identifies two types of entrepreneurial activity, namely opportunity-driven early-stage entrepreneurship activity (OEA) and necessity-driven early-stage entrepreneurial activity (NEA). We decided to include these two variables in the analysis, as several theoretical and empirical studies have emphasized that the effect of entrepreneurship on economic growth varies not only according to the stage of economic development of a country, but also according to the types of entrepreneurship. Thus, the objective of our research is to examine the extent to which the effect of entrepreneurial activity on economic growth varies, both according to the stage of economic development of the countries and according to the types of entrepreneurial activity. According to the GEM methodology, the definitions given for the OEA and NEA are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the variables considered in the analysis.

In our econometric model, we have included, in addition to the variables mentioned above, several control variables. The control variables are represented by different factors, suggested by the theories of economic growth, that would affect the economic growth: the investment ratio (proxied through the gross capital formation in percentage of GDP), knowledge (measure by research and development expenditure and education level), unemployment rate, government expenditures, population growth, and economic openness.

In Table 2, we describe the dependent, independent, and control variables used in this study, including their definition and sources.

Several studies in the literature [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] have provided evidence that entrepreneurship can be considered a micro driver of innovation and economic growth. As shown in the literature [6], entrepreneurial activity is needed because, in the context of globalization, it is an important determinant of innovation, productivity growth, competitiveness, economic growth, and job creation. Because of these reasons, nowadays entrepreneurship has become a key policy issue (see at EU level, the entrepreneurship 2020 action plan [46]) and the decision makers at national and regional levels have to give importance to the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development.

Moreover, there are studies [47,48] pointing out that country-specific effects are important when analyzing the relationship between different types of entrepreneurship and economic growth. The nature of entrepreneurship is likely to be different in higher and lower income countries, hence the impact on economic growth may also differ [16,25]. Therefore, we have chosen to group the countries according to their level of economic development.

Based on the review of the empirical studies focused on the relation of entrepreneurship with economic growth, we found that a variety of indicators for measuring entrepreneurship and economic growth were used, which has led to a certain heterogeneity of econometric methods and the results obtained.

The main objective of our paper is to analyze the effect of different types of entrepreneurship on economic growth using a panel data of 22 countries for the period 2002–2018. The countries are divided into countries in transition between efficiency and innovation (5 countries from the sample) and innovation-driven countries (17 countries from the sample) based on classification made by Schwab and Sala-i-Martin [35] and based on the amount of GDP per capita (breakpoint 17,000 US).

In order to achieve our purpose, starting from those presented in the previous sections, we formulated a set of hypotheses that will guide our future empirical analysis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Higher levels of total early stage entrepreneurs are positively related to GDP per capita.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Countries with higher levels of opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs will have higher economic growth rates.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Countries with higher levels of necessity-motivated entrepreneurs will have lower economic growth rates.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The effects of the OEA and NEA on the level of economic growth differ according to the stage of economic development of countries.

To test our hypotheses, we used panel data estimation techniques, and we estimated OLS model adapted to panel data, random-, and fixed-effects models. The general equation of our model is presented below:

where: i represents the country and t is time; ∆ ln yit: first-differenced logarithm of the GDP per capita; enit: the types of entrepreneurship; xit: the control variables; μit: the error term.

∆ lnyit = β1enit + β2xit + μit

We ran a descriptive statistics analysis, the correlation analysis, and finally we applied the regression models to our data. In order to identify which model is a better fitter to our data, we used the Hausman specification test and the redundant fixed effects test. The results of the Hausman test for TEA, OEA, and NEA strongly accept the null hypothesis because the p value = 1.000 (H0: Random effect is preferred). Therefore, the random effects model is preferred for our sample. On the other hand, the results obtained for the redundant fixed effects test strongly reject H0 (as p values = 0.000) the null hypothesis (H0: The fixed effects are redundant). These emphasize that the fixed effects are statistically significant. Because we have obtained a contradiction between these two tests, we consider the pooled OLS regression as the best model explaining the relations between our variables [49].

4. Results and Discussions

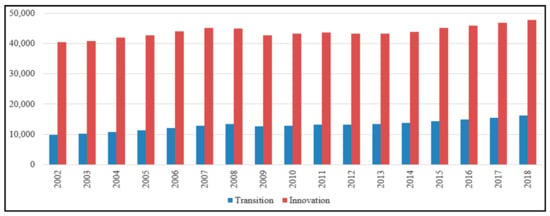

Analyzing the average GDP per capita for the European countries considered in the analysis (see Figure 1), we can point out the differences between the two groups of countries. The average GDP per capita for the transition countries represents a quarter of the GDP per capita of the innovation-driven countries. Moreover, both groups had an ascending trend until 2008, after the outburst of the recent financial crisis the average GDP per capita for both groups of countries registered a decrease. Starting with 2013, the European economies have begun to recover and have resumed their upward trend, both for developed and less developed countries.

Figure 1.

The dynamics of average GDP per capita for the countries considered in the analysis, by groups of countries (authors’ own elaboration).

For identifying the differences between the two groups of countries, we have compared the means for all the variables. As illustrated in Table 3, the two groups of countries considered for the analysis are very different. Contrary to developed countries, the countries that have emerging countries register lower growth rates, lower R&D, and government expenditures, a decrease of population, higher unemployment rates, and higher rates of inflation. However, the countries included in the group with economies in transition have an increased level of economic openness and a higher percentage of the population who have completed at least upper secondary education. In countries with economies in transition there is a higher entrepreneurial activity, but especially motivated by necessity. Due to the high unemployment rates and the lack of other opportunities to earn the income needed to live in these countries, many people decide to open a business. On the other side, the innovative economies register higher levels of opportunity and entrepreneurial activity. Favorable economic conditions offer many opportunities on the market so that, in countries with innovative economies, an increased number of people decide to open a business in order to obtain profits as a result of capitalizing on the opportunities.

Table 3.

Average values of indicators for transition countries and innovation-driven countries.

Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the variables. All the variables included in the study have a significant variability, which allows us to apply to future analyses. The number of observations varies due of the availability of data, because some of the variables are available only for a part of the considered period. The level of GDP per capita, for our sample, varies between a minimum of 5.624 US dollar in Romania (in 2002) and a maximum of 92.121 US dollar in Norway (in 2018). These results confirm once again the significant differences that exist between developed and less developed economies from Europe.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

With regards to entrepreneurship, we also observed significant variations. The level of total early stage entrepreneurship varies between 1.63% of working age population in France (in 2003) and 14.20% in Slovak Republic (in 2011). The opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs vary between a minimum of 18.38% of working age population in Italy (in 2013) and a maximum of 80.47% in Denmark (in 2006). The level of necessity entrepreneurs also varies significantly between a minimum of 3% of working age population in France (in 2002) and 50% in Croatia (in 2005). The control variables also vary significantly between the European countries considered in the analysis.

Separately, we tested the correlation between variables (see Table 5). The results obtained emphasize the presence of multicollinearity only for the variables that measure entrepreneurship. Therefore, the necessity- and the opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs are strongly negatively correlated (0.691, p = 0).

Table 5.

Correlation matrix.

The regression analysis results (see Table 6) point out that entrepreneurship is a significant factor influencing the economic growth. Starting from the results for the full sample of countries, we found that all three types of entrepreneurship significantly influence the economic growth, expressed by GDP per capita.

Table 6.

Regression analysis.

Model 1 and 2 emphasize that TEA and OEA are important determinants of the level of economic growth in all the European countries included in the sample. Comparatively, necessity-driven entrepreneurial activity has a strong negative effect on GDP per capita. Entrepreneurial activity (TEA) has a positive and statistically significant impact (p < 0.10) on GDP per capita. This result suggests that the creation of new businesses is positively and statistically significant related to economic growth. Our findings are consistent with the ones of previous studies [4,6,9,11,12,16,17,19,20,23,50,51], which also found a positive relation between TEA and economic growth. We also found that the estimated size of the effect appears to be very limited, respectively, a 10% increase in the TEA rate would lead to an increase of only 0.06% of GDP per capita.

As regards the types of entrepreneurship analyzed, we observed that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (OEA) has a statistically significant positive and powerful effect (p < 0.01) on economic growth of European countries, which could be translated in that opportunity entrepreneurs demonstrates innovative capabilities and exploit unidentified opportunities in the non-traditional industries [52]. This is consistent with the results of several other studies [15,20,23,28,43,44,53,54] which show that entrepreneurial activity based on innovation has a positive impact on economic growth. In terms of necessity-driven entrepreneurship (NEA), the results for the full sample of countries show that this type of entrepreneurship would have a negative and strongly significant impact (p < 0.01) on economic growth. Such a result would not seem surprising because this type of entrepreneurship is represented by people who are forced to start their own business due to lack of jobs and who are usually not very productive [21]. It is also claimed that necessity-driven entrepreneurs possess fewer endowments of human capital and entrepreneurial capacity [12] and therefore could not run a new business, leading to economic growth. Similarly, Poschke [55] points out that this type of entrepreneur has lower education, runs small businesses, and expects their businesses to grow less.

Necessity-driven entrepreneurs provide employment, and usually are interested in ensuring the necessary means of living due to no other job opportunities, and are not interested in innovation and growth. NEA has a significant but negative coefficient, showing that the increased level of necessity entrepreneurship not only stimulates economic growth, but it might even result in a decrease in economic growth. As shown by Valliere and Peterson [15], necessity-motivated entrepreneurs are contributing to the economy by reducing the unemployment rate, but not by increasing the total output. Our results are in agreement with the ones of Liñán and Fernandez-Serrano [56], Boudreaux [28]. Some studies (such as [12,57]) have indicated that NEA has no or a negative effect on economic growth because its marginal productivity is zero or even negative. The negative relationship could be explained by the fact that not all new businesses will have equal effects on economic growth [52].

Models 4, 5, and 6 analyze only the group of transition countries. For this group of countries, only TEA and OEA have a statistically significant relationship with economic growth, both positive. As described above, the increase of the total early stage entrepreneurs can stimulate the increase of the economy because the creation of new business generates new jobs, more competition, and can increase productivity, all with positive macroeconomic effects. Regarding necessity-driven entrepreneurship (NEA), we find that this type of entrepreneurship is positively related to economic growth, but the estimated coefficient is found to be insignificant, in line with the findings revealed by Wong et al. [12], Urbano, and Aparicio [19]. Our results might be surprising if we consider the high level of the NEA rate, which is double compared to the level registered in the innovation-driven countries (see Table 3). However, the insignificant connection of this type of entrepreneurship with the economic growth suggests that a simple creation of a new business is not sufficient to register an increase in GDP per capita [15]. Additionally, in the case of the insignificant relationship between the NEA rate and economic growth, according to Urbano and Aparicio [19], a possible explanation could be based on the U-shaped form, invoked by some studies [24,25,26], which found that some developing countries have a negative relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth, while other developing countries have a flatter relationship between these two variables. The statistically insignificant effect of necessity-driven entrepreneurship on economic growth does not mean that this type of entrepreneurship should be discouraged because it may contribute to lowering the unemployment rate, which would improve the economic performance of a country [25].

The transition countries are characterized by the presence of a large number of necessity-motivated entrepreneurs which are not necessary stimulating the growth of the economy, as self-employment in the developing world tends to be low productivity employment [58]. In these conditions, an increase in the number of opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs can represent a factor driving the growth. Usually, opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs are considered to be the ones that apply innovation. Therefore, as shown in the literature [43,44], the entrepreneurs that apply innovation have an extraordinary economic impact, as they develop new technologies, create new jobs, and enhance the revitalization capacity of territories.

Models 7,8, and 9 analyze only the group of innovation-driven countries. For these countries, only TEA and NEA have sta+tistically significant coefficients. The early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) is positively and significantly (p < 0.10) associated with economic growth, showing once again that regardless of the level of economic development of the country, the extent of entrepreneurial activity can be seen as a factor stimulating economic growth. The result is similar with the one obtained by Van Stel et al. [25], Hessels and van Steel [16], Stam and van Stel [14], Amaghouss and Ibourk [59], Urbano and Aparicio [19]. In the case of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (OEA), we find a positive (but statistically insignificant) association with economic growth. According to Valliere and Peterson [15], one possible explanation would be that in these countries, opportunity-based entrepreneurs do not have high-growth expectations of their businesses due to either obstacles in the economic environment they are facing or the goals of growing their business more modestly. However, the authors point out that as opportunity-based entrepreneurs are innovative people, countries that encourage entrepreneurial activity based on innovation could see an improvement in economic performance. For necessity-driven entrepreneurship, we obtained a negative coefficient which was statistically significant (in line with the results obtained by Boudreaux [28]), showing that higher levels of this type of entrepreneurship will determine a decrease in the economic growth of European innovation-driven countries. Necessity-driven entrepreneurs are usually people who decide to open their own business because they do not have another option of obtaining earnings for living and might not be interested at all at innovating or growth. As shown in the literature [12,58], only certain activities and functions of entrepreneurs may stimulate growth, and excessively high self-employment by necessity may actually inhibit economic development of countries. Ivanović-Djukić et al. [23] showed that, in developed countries, the role of necessity entrepreneurs in the economy may be bigger than previously assumed. Additionally, it is possible in developed countries for the difference between the opportunity- and necessity-motivated entrepreneurs to not be as clear-cut as in developing countries [23].

From the three types of entrepreneurship analyzed (TEA, OEA, NEA), we first found that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship seems to be more important for achieving GDP per capita growth, both at the level of the entire sample of countries, but also at the level of the group of countries in transition. On the other hand, necessity-driven entrepreneurship has the smallest contribution to economic growth, compared to TEA and OEA. These findings from our analysis are consistent with those of other studies (such as [57]) and suggest that entrepreneurship’s contribution to economic growth is different, depending on the forms of entrepreneurial activity.

The results of the regression analysis (see Table 6) show that the impact of entrepreneurship on the economic growth is different depending on the stage of economic development of the countries. Thus, the contribution of total early-stage entrepreneurial activity in transition countries (coefficient is 0.003) is lower compared to European countries based on innovation (where coefficient is 0.005). A possible explanation is related to the fact that in transition countries, the positive effects of entrepreneurship are limited due to its significant presence in low productivity activities, but also due to the presence of macroeconomic problems, such as the high share of grey economy, corruption, unfair competition, etc. [23]. For the opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship, we also obtained different results when we took into consideration the level of economic development of the countries. Thus, the magnitude and the statistical significance of the estimated coefficient indicate a stronger impact on economic growth in transition countries compared to the group of innovation-driven countries. On the other hand, necessity-driven entrepreneurship does not significantly affect economic growth at the level of the transition countries group, instead it negatively and significantly influences economic growth in innovation-driven countries.

Our first hypothesis, that higher levels of total early stage entrepreneurs are positively related to GDP per capita, is supported. Regardless of the level of development of the 22 European countries, TEA is a significant and positive determinant of GDP per capita. Our second and third hypotheses are partially supported, because we found that higher levels of opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs have a significantly and positive influence on economic growth only for the transition countries, and higher levels of necessity-motivated entrepreneurs will significantly negatively influence only the economic growth of innovation driven countries. The different results obtained between the two groups of countries sustain the fourth hypothesis.

Regarding the control variables, for all countries considered in the analysis, there are several indicators that have a significant effect on economic growth: gross capital formation, R&D expenditures, education, unemployment rate, government expenditures, and population growth. Economic openness and inflation rate do not have statistically significant coefficients. Furthermore, the coefficients of some of the control variables, in particular R&D expenditures, government expenditures, and population growth, were found to be statistically significant, for the entire sample of countries and for both groups of countries.

Regarding the gross capital formation (GCF) control variable, surprisingly, the estimates obtained have shown a negative and strongly significant impact on the economic growth at the level of the entire sample of countries. For both groups of countries, the effect is not significant, but it is positive for the countries in transition, and negative for the countries based on innovation. Statistically insignificant coefficients would suggest that GCF would not make a significant contribution to economic growth, in line with Zaki’s [52] findings.

In the case of R&D expenditures, the coefficient is positive and statistically significant for all models (except model 7), which indicates that investments in research and development would be an important contributor to the economic growth. The explanation would be that a high level of R&D expenditures would allow individuals and companies to assimilate new knowledge and apply them to create new products or to identify new business opportunities, which would stimulate economic growth [10]. Our results are in line with those obtained by Acs et al. [4], Portela et al. [51].

The results regarding the education variable indicate a positive and statistically significant relationship (with the exception of model 4) for both groups of countries, which suggests that the level of education of the population can be an important determinant of economic growth. Our results are in agreement with those of Acs et al. [4], Acs et al. [5], Portela et al. [51], Bosma et al. [20], and Chen et al. [60]. For the entire sample of countries, we found a negative relationship, which shows that a higher percentage of people aged 25-64 who have successfully completed at least upper secondary education does not ensure the means for obtaining economic growth [61].

Government expenditures and population growth are positively and significantly linked to economic growth in all models, which suggests their quality as important determinants of economic growth. These findings are similar to the ones of Amaghouss and Ibourk [59] and Simionescu et al. [62].

Regarding the unemployment rate, we obtained a negative relationship between this and economic growth, in line with the results of some studies [22,57,63]. This shows that an increase in the unemployment rate causes a decrease in the level of economic growth.

In the case of the economic openness variable, our results indicate that the coefficient has a positive sign in all the models, which would suggest that this variable would positively influence the economic growth. However, economic openness would have a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth only in the case of transition countries. As indicated by the statistical data (see Table 3) at the level of the group of countries in transition (five countries), the openness ratio is on average higher (111.76%) compared to the average value of the indicator (93.05%) at the level of innovation-driven countries (17 countries). Such a situation could be explained by the fact that the countries in transition have experienced an intensification of trade, especially with the EU countries, both during the pre-accession EU and post-accession period. Therefore, it would seem that in the case of this group of countries, increasing the economic openness would have a significant contribution to the recording of faster economic growth. Openness to trade has a positive impact on economic growth both in the short and long run [64], but countries exporting higher quality products and new varieties grow more rapidly [65]. Moreover, studies in the literature [66] have pointed out the positive effect of economic openness in developing countries and emphasized that the magnitude of trade openness to enhance growth is higher in developing countries than in OECD countries.

The inflation rate has a negative and statistically significant coefficient only for the innovation-driven countries showing that higher rates of inflation in these countries determines a slowdown in economic growth. These findings are in line with the results of Ayyoub et al. [67] and Akinsola and Odhiambo [68] which point out that the effects of inflation on economic growth depend on country-specific characteristics, and obtained a negative relationship between inflation and growth, especially in developed economies.

Our models have statistically significant values for F statistics. The value for the adjusted R squared is higher than 65%. As shown in Table 6, adjusted R-squared is between 0.657 and 0.837, which means that above 65% of the variation of economic growth for the 22 countries is explained by the variation of the independent variables. Therefore, in the European countries considered, the level of economic growth depends on the level of entrepreneurship and, especially, on the motivation of choosing to be an entrepreneur.

5. Conclusions

Considering a set of data for 22 European countries, the findings of our study sustain the positive impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. Additionally, our findings are in line with the conclusions of previous research which point out the different role of entrepreneurship on economic growth, taking into account the type of entrepreneurship considered, but also the level of economic development.

At the level of the entire sample of European countries, the results suggest that entrepreneurial activity approached through early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA), opportunity-driven early-stage entrepreneurship activity (OEA), and necessity-driven early-stage entrepreneurial activity (NEA) influences the economic growth. All types of entrepreneurship described above exert a significant effect on economic growth. We found a positive and statistically significant relationship between early-stage entrepreneurial activity and economic growth, which suggests that expanding entrepreneurial activity would stimulate economic growth. We also found that opportunity-driven early-stage entrepreneurship activity seems to be more important for achieving economic growth. In contrast, necessity-driven entrepreneurship is negatively and significantly related to economic growth. Such a relationship would not be surprising if we consider the particularities of necessity-driven entrepreneurs. Overall, our empirical investigation suggests that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and early-stage entrepreneurship would be key factors in stimulating economic growth across the sample of European countries.

The comparative analysis of the two groups of countries (transition countries vs. innovation-driven countries) shows that the role of the three types of entrepreneurship on economic growth is not homogeneous. Our findings are as follows: the contribution of total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) to economic growth is lower in transition countries (coefficient is 0.003) compared to the innovation-driven countries (coefficient is 0.005), although the TEA rate is higher in the case of the first group of countries (7.88% vs. 6.23%). One possible explanation is related to the fact that in transition countries, the positive effects of entrepreneurship are limited due to its significant presence in activities with low productivity, but also due to some macroeconomic problems that they face. In the case of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (OEA), surprisingly, we found a positive and statistically significant impact on economic growth in transition countries. Comparatively, in the case of innovation-driven countries, the OEA is positively linked, but insignificant to the economic growth. Regarding necessity-driven entrepreneurship, we note that its effects on economic growth are totally different in the two groups of countries, as follows: this type of entrepreneurship does not significantly affect the economic growth at the level of the transition countries, instead it negatively and significantly influences the economic growth in innovation-driven countries. The results regarding the NEA effect could be surprising if we consider the level of this type of entrepreneurship, which is double compared to the level registered in innovation-driven countries (31.29% vs. 15.91%).

Considering the significant role played by entrepreneurship for the economic growth and the results of our research, we consider it of interest that the decision makers focus more on the adoption and implementation of measures to eliminate the obstacles in the macroeconomic environment that entrepreneurs face, but also on measures to support innovative entrepreneurial activities.

Our study is important for policymakers because it highlights the importance of why individuals decide to enter into entrepreneurship. An increased share of entrepreneurs motivated by necessity in the economy can lead to long-term negative effects on economic growth, because these entrepreneurs do not focus on applying innovation in the production process and on increasing the business performance, but on obtaining the necessary income for living. Implicitly, decision makers should issue policies to stimulate the business environment and create new business opportunities, stimulating the multiplication of entrepreneurs motivated by opportunity generating positive effects on the economy.

Additionally, sustained economic growth has positive long-term effects on businesses. Thus, a high quality of the entrepreneurial activities, at present, generates positive effects on the economic growth, and subsequently determines an improvement on the business environment. The results of our study help managers become aware of the role their innovative activity and performance plays in improving the economic and business environment.

The analysis of the control variables indicates that most of them would be key factors of the economic growth in the investigated European countries.

The main limit of our analysis comes from the relatively small size of the sample (22 European countries, of which 5 included in the group of countries in transition and 17 in the innovation-driven countries group). In our future analysis, we will expand both the sample of countries and also the way we investigate the nexus between entrepreneurship and economic growth, by investigating the effects of other types of entrepreneurs (such as nascent entrepreneurs, owner–managers of established businesses etc.). Additionally, in future research we intend to extend the analysis to also include the role played by the uncertainty, risk, and the monetary policy for entrepreneurial activity and the economic growth of nations.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived the study and contributed equally to the writing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.W. Economic growth and capital accumulation. Econ. Rec. 1956, 32, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Polit. Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Carlsson, B. Growth and Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Assessment; No. 5409; CEPR Discussion Paper; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2005; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=893068 (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Carlsson, B. Growth and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 39, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Acs, Z.J., Audretsch, D.B., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 437–471. [Google Scholar]

- Van Stel, A.; Carree, M. Business ownership and sectoral growth: An empirical analysis of 21 OECD countries. Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 389–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B. Entrepreneurship capital and economic growth. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2007, 23, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, P. Exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities: The impact of entrepreneurship on growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 28, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.K.; Ho, Y.P.; Autio, E. Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: Evidence from GEM data. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 30, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; van Stel, A. Types of Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth; Working Paper Series; UNU-WIDER: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2009; p. 49. Available online: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:60/wp2009-049.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Valliere, D.; Peterson, R. Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Evidence from emerging and developed countries. Entrep. Region Dev. 2009, 21, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; van Stel, A. Entrepreneurship, export orientation, and economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 37, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M.Á.; Méndez, M.T. Entrepreneurship, economic growth, and innovation: Are feedback effects at work? J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepojević, V.; Djukić, M.I.; Mladenović, J. Entrepreneurship and economic development: A comparative analysis of developed and developing countries. Facta Universitatis, Series: Economics and Organization; University of Niš: Niš, Serbia, 2016; Volume 12, pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S. Entrepreneurship capital types and economic growth: International evidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2016, 102, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.; Content, J.; Sanders, M.; Stam, E. Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.; McCarthy, N.; O’Connor, M. The role of entrepreneurship in stimulating economic growth in developed and developing countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1442093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O.; Gordievskaya, A.; Procházka, D.A. Investigating the relationship between entrepreneurship and regional development: Case of developing countries. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović-Djukić, M.; Lepojević, V.; Stefanović, S.; van Stel, A.; Petrović, J. Contribution of Entrepreneurship to Economic Growth: A Comparative Analysis of South-East Transition and Developed European Countries. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2018, 16, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Carree, M.; van Stel, A.; Thurik, R.; Wennekers, S. Economic development and business ownership: An analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Bus. Econ. 2002, 19, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stel, A.; Carree, M.; Thurik, R. The effect of entrepreneurial activity on national economic growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennekers, S.; van Wennekers, A.; Thurik, R.; Reynolds, P. Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; Hartog, C.; van Stel, A.; Thurik, R. Ambitious entrepreneurship, high-growth firms and macroeconomic growth. In The Dynamics of Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Data; Minniti, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C.J.; Caudill, S. Entrepreneurship, Institutions, and Economic Growth: Does the Level of Development Matter? arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.02934. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1903/1903.02934.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Sternberg, R.; Wennekers, S. Determinants and effects of new business creation using global entrepreneurship monitor data. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M.; Lévesque, M. Entrepreneurial types and economic growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfatia, H.A. Impact of uncertainty on high frequency response of the US stock markets to the Fed’s policy surprises. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2014, 54, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfatia, H.A. Monetary policy’s time-varying impact on the US bond markets: Role of financial stress and risks. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüning, H. Asset market response to monetary policy news from SNB press releases. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 40, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüning, H. Swiss National Bank communication and investors’ uncertainty. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2019, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Sala-I-Martin, X. The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K.; Sala-I-Martin, X. The Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The Global Competitiveness Report 2018; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. GEM Key Indicators. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/data (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M.; Lehmann, E. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennekers, S.; van Stel, A.; Carree, M.; Thurik, R. The relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development: Is it U-shaped? Found. Trends Entrep. 2010, 6, 167–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pernía, J.L.; Jung, A.; Peña, I. Innovation-driven entrepreneurship in developing economies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, H.A.; Akhtar, A. The Role of Innovative Entrepreneurship in Economic Development: A Study of G20 Countries. Manag. Stud. Econ. Syst. 2016, 3, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.; Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 51–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan: Reigniting the Entrepreneurial Spirit in Europe. In European Commission-DG Enterprise & Industry; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo, I.; Thurik, R. Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Europe. ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2004-106-ORG. 2004. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=636815 (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Acs, Z.J., Audretsch, D.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 557–594. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.M. Linear Regression Models for Panel Data Using SAS, Stata, LIMDEP, and SPSS; Indiana University Working Paper: Bloomington, UN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin, M. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth: An Obvious Conjunction. The Institute for Development Strategies, Indiana University. 2000. Available online: http://econwpa.wstl.edu/eps/dev/papers/0110/0110010.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Portela, M.; Vázquez-Rozas, E.; Neira, I.; Viera, E. Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Macroeconomic analysis and effects of social capital in the EU. In Entrepreneurship–Born, Made and Educated; Burger-Helmchen, T., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 249–264. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/entrepreneurship-born-made-and-educated/entrepreneurship-and-economic-growth-macroeconomic-analysis-and-effects-of-social-capital-in-the-eu (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Zaki, I.M.; Rashid, N.H. Entrepreneurship impact on economic growth in emerging countries. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 7, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Entrepreneurship capital and regional growth. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2005, 39, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Resolving the knowledge paradox: Knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship and economic growth. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poschke, M. Entrepreneurs out of necessity: A snapshot. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2013, 20, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fernandez-Serrano, J. National culture, entrepreneurship and economic development: Different patterns across the European Union. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Varga, A. Entrepreneurship, agglomeration and technological change. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, D.N. By choice and by necessity: Entrepreneurship and self-employment in the developing world. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014, 26, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaghouss, J.; Ibourk, A. Entrepreneurial Activities, Innovation and Economic Growth: The Role of Cyclical Factors: Evidence from OECD Countries for the Period 2001-2009. Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 6, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.W.; Fu, L.W.; Wang, K.; Tsai, S.B.; Su, C.H. The Influence of Entrepreneurship and Social Networks on Economic Growth—From a Sustainable Innovation Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Desai, S. Entrepreneurship and economic development in cities. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2015, 55, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, M.; Lazányi, K.; Sopková, G.; Dobeš, K.; Balcerzak, A.P. Determinants of Economic Growth in V4 Countries and Romania. J. Compet. 2017, 9, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetai, B.T.; Mustafi, B.F.; Fetai, A.B. An empirical analysis of the determinants of economic growth in the Western Balkans. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2017, 64, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keho, Y. The impact of trade openness on economic growth: The case of Cote d’Ivoire. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2017, 5, 1332820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchet-Bourdon, M.; le Mouël, C.; Vijil, M. The relationship between trade openness and economic growth: Some new insights on the openness measurement issue. World Econ. 2017, 41, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, J.; Yusop, Z.; Habibullah, M.S.; Chin, L. Openness and Economic Growth in Developing and OECD Countries. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2018, 12, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyoub, M.; Chaudhry, I.S.; Farooq, F. Does Inflation Affect Economic Growth? The case of Pakistan. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 31, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Akinsola, F.A.; Odhiambo, N.M. Inflation and economic growth: A review of the international literature. Comp. Econ. Res. 2017, 20, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).