Investing In CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers

Abstract

1. Introduction

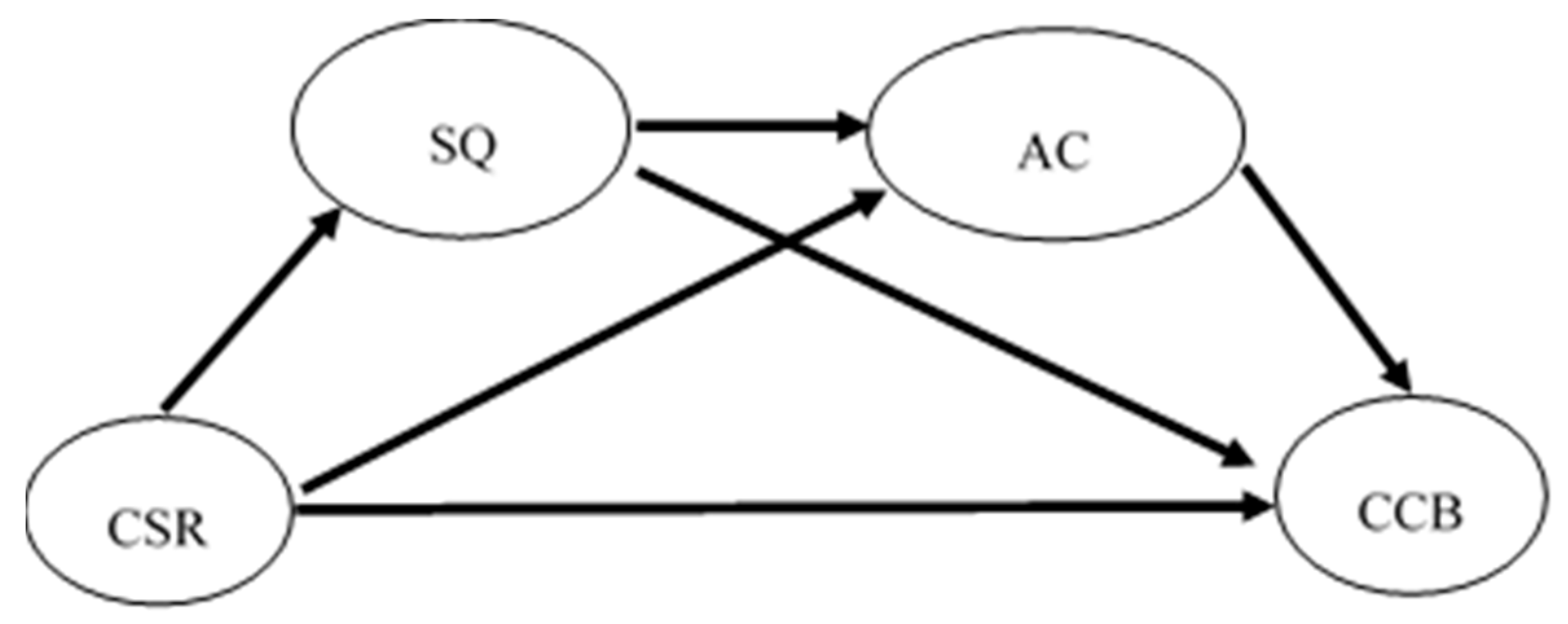

2. Theorization of the Study

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Research Methodology

5. Findings

5.1. Measurement Equivalence

5.2. Common Method Variance

5.3. Hypotheses Testing

6. Discussions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Usefulness of study

7. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

References

- Nguyen, Q.; Nisar, T.M.; Knox, D.; Prabhakar, G.P. Understanding customer satisfaction in the UK quick-service restaurant industry: The influence of the tangible attributes of perceived service quality. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.B. Customer loyalty in the fast food restaurants of Bangladesh. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2791–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, N.A. Fast food: 2nd largest industry in Pakistan. 2019. Available online: http://foodjournal.pk/2016/July-August-2016/PDF-July-August-2016/Exclusive-article-Dr-Noor-Fast-Food.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Islam, T.; Ahmed, I.; Ali, G.; Ahmer, Z. Emerging trend of coffee cafe in Pakistan: Factors affecting revisit intention. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2132–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Gretzel, U. What motivates consumers to write online travel reviews? Info. Technol. Tour. 2008, 10, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Chen, P.-J.; Schuckert, M. Managing customer citizenship behaviour: The moderating roles of employee responsiveness and organizational reassurance. Tour. Manag. 2008, 59, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartikowski, B.; Walsh, G. Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.; Yen, C.; Chin, K. Participative customers as partial employees and service provider workload. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claycomb, C.; Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Inks, L.W. The customer as a productive resource: A pilot study and strategic implications. J. Bus.Strateg. 2001, 18, 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, P.K.; Chase, R.B.; Margulies, N. Motivating the client/employee system as a service production strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1983, 8, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Managing foodservice productivity in the long term: Strategy, structure and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1990, 9, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Nataraajan, R.; Gong, T. Customer participation and citizenship behavioral influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A. Personality antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in online shopping situations. Psych. Market. 2014, 31, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Luo, S.J.; Yen, C.H.; Yang, Y.F. Brand attachment and customer citizenship behaviors. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Lotz, S.L. Exploring antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in services. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Saunders, S.G.; Lisita, I.T.; de Beer, L.T. The importance of customer citizenship behaviour in the modern retail environment: Introducing and testing a social exchange model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Poon, P.; Zhang, W. Brand experience and customer citizenship behavior: The role of brand relationship quality. J. Consumer Market. 2017, 34, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T.; Lee, H. The impact of other customers on customer citizenship behavior. Psych. Market. 2013, 30, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P.; Suárez-Acosta, M.A.; Guerra-Báez, R.M. Customer citizenship as a reaction to hotel’s fair treatment of staff: Service satisfaction as a mediator. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Sun, H.; Chang, Y.P. Effect of social support on customer satisfaction and citizenship behavior in online brand communities: The moderating role of support source. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 31, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Lin, P.; Qiu, Z.H.; Zhao, A. A framework of memory management and tourism experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Volume II: Separation, anxiety and anger. In Attachment and Loss: Volume II: Separation, Anxiety and Anger; The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Grønhaug, K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer brand advocacy: The role of moral emotions, attitudes, and individual differences. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engizek, N.; Yasin, B. How CSR and overall service quality lead to affective commitment: Mediating role of company reputation. Soc. Resp. J. 2017, 13, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rasool, A. Customer engagement in the service context: An empirical investigation of the construct, its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Gao, Y.; Shah, S.S.H. CSR and Customer Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Costa, P. The effect of the consumer perceptions of CSR in brand love. Presented in 12th global brand conference of the Academy of Marketing, School of Business & Economics, Linnaeus Univesity, Kalmar, Sweden, 26–27 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Conklin, M.; Cranage, D.A.; Lee, S. The role of perceived corporate social responsibility on providing healthful foods and nutrition information with health-consciousness as a moderator. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plewa, C.; Conduit, J.; Quester, P.G.; Johnson, C. The impact of corporate volunteering on CSR image: A consumer perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as good soldiers: Examining citizenship behaviours in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Camacho, M.Á.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Cossío-Silva, F.J. Customer participation and citizenship behavior effects on turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Shekhar, V.; Lassar, W.M.; Chen, T. Customer engagement behaviors: The role of service convenience, fairness and quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jiménez, J.V.; Ruiz-de-Maya, S.; López-López, I. The impact of congruence between the CSR activity and the company’s core business on consumer response to CSR. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2017, 21, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poolthong, Y.; Mandhachitara, R. Customer expectations of CSR, perceived service quality and brand effect in Thai retail banking. Int. J. Bank Market. 2009, 27, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, W.; Ouschan, R.; Burton, H.J.; Soutar, G.; O’Brien, I.M. Customer engagement in CSR: A utility theory model with moderating variables. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Rialp, J. How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Sivadas, E.; Garbarino, E. Customer satisfaction, perceived risk and affective commitment: An investigation of directions of influence. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Pinto, T. Relationship quality determinants and outcomes in retail banking services: The role of customer experience. J Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béal, M.; Sabadie, W. The impact of customer inclusion in firm governance on customers’ commitment and voice behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurier, P.; Séré de Lanauze, G. Impacts of perceived brand relationship orientation on attitudinal loyalty: An application to strong brands in the packaged goods sector. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1602–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Nayak, J.K. Hospitality branding in emerging economies: An Indian perspective. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Market. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, M.; Bolton, R.N. Why attachment security matters: How customers’ attachment styles influence their relationships with service firms and service employees. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y. The validation of the generic service quality dimensions: An alternative approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Dawes, P.L.; Massey, G.R. An extended model of the antecedents and consequences of consumer satisfaction for hospitality services. Eur. J. Market. 2008, 42, 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. The effects of customer justice perception and affect on customer citizenship behavior and customer dysfunctional behavior. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate data analysis: Global edition; Prentice hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Gleser, G.C.; Nanda., H.; Rajaratnam, N. The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. App. Psych. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Item | α | Mean | SD | Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR | CSR1 | 0.94 | 4.10 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| CSR2 | 3.90 | 0.89 | 0.94 | ||||

| CSR3 | 3.75 | 0.85 | 0.87 | ||||

| CSR4 | 4.05 | 0.92 | 0.73 | ||||

| Service Quality Perceptions | PQ1 | 0.89 | 4.20 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.79 |

| PQ2 | 4.25 | 0.89 | 0.82 | ||||

| PQ3 | 4.15 | 0.88 | 0.79 | ||||

| SB1 | 0.93 | 4.30 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.81 | |

| SB2 | 4.45 | 0.35 | 0.93 | ||||

| SB3 | 4.25 | 0.60 | 0.86 | ||||

| SB4 | 4.38 | 0.54 | 0.90 | ||||

| Affective Commitment | AC1 | 0.90 | 4.05 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| AC2 | 3.90 | 0.97 | 0.93 | ||||

| AC3 | 3.87 | 1.01 | 0.89 | ||||

| Customer Citizenship Behaviour | CCB1 | 0.82 | 3.87 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.83 |

| CCB2 | 3.57 | 1.18 | 0.74 | ||||

| CCB3 | 3.84 | 0.97 | 0.89 | ||||

| CCB4 | 3.90 | 0.85 | 0.90 | ||||

| CCB5 | 3.75 | 0.99 | 0.81 | ||||

| CCB6 | 3.70 | 1.03 | 0.85 |

| PCSR | SQ | AC | CCB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSR | 0.79 a | |||

| SQ | 0.65 b | 0.84 | ||

| AC | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.90 | |

| CCB | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.92 |

| Measurement Weights | Gender (Male 361, Female 308) | Status (Students 529, Professionals 140) | Visit (Regular 562, Occasional 107) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x2 | df | P | x2 | Df | p | x2 | df | P | |

| Unconstrained | 324.68 | 178 | 0.139 | 409.17 | 263 | 0.201 | 423.60 | 272 | 0.197 |

| Constrained | 302.24 | 163 | 387.53 | 246 | 400.21 | 261 | |||

| Difference | 22.44 | 15 | 21.64 | 17 | 23.39 | 11 | |||

| Hypotheses | Path | Estimate | Se | P | CI | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H 1 | PCSR–CCB | 0.4298 | 0.023 | 0.0000 | [0.310; 0.421] | Supported |

| H 2 | PCSR–SQ | 0.4423 | 0.019 | 0.0000 | [0.293; 0.374] | Supported |

| H 3 | PCSR–AC | 0.3965 | 0.015 | 0.0001 | [0.316; 0.395] | Supported |

| H 4 | SQ–AC | 0.2301 | 0.023 | 0.0000 | [0.404; 0.357] | Supported |

| H 5 | SQ–CCB | 0.4219 | 0.027 | 0.0023 | [0.390; 0.462] | Supported |

| H 6 | AC–CCB | 0.3921 | 0.017 | 0.0043 | [0.382; 0.492] | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Effect | BootSE | Boot LLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | PCSR-SQ-AC-CCB | 0.1405 | 0.0069 | 0.0019 | 0.0281 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, I.; Nazir, M.S.; Ali, I.; Nurunnabi, M.; Khalid, A.; Shaukat, M.Z. Investing In CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031158

Ahmed I, Nazir MS, Ali I, Nurunnabi M, Khalid A, Shaukat MZ. Investing In CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031158

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Ishfaq, Mian Sajid Nazir, Imran Ali, Mohammad Nurunnabi, Arooj Khalid, and Muhammad Zeeshan Shaukat. 2020. "Investing In CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031158

APA StyleAhmed, I., Nazir, M. S., Ali, I., Nurunnabi, M., Khalid, A., & Shaukat, M. Z. (2020). Investing In CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers. Sustainability, 12(3), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031158