A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The construction of a collaborative decision-making process, through the establishment and activation of a Creative Living Lab;

- The elicitation of values through deliberative evaluation techniques;

- The co-evaluation role within the collaborative decision-making process.

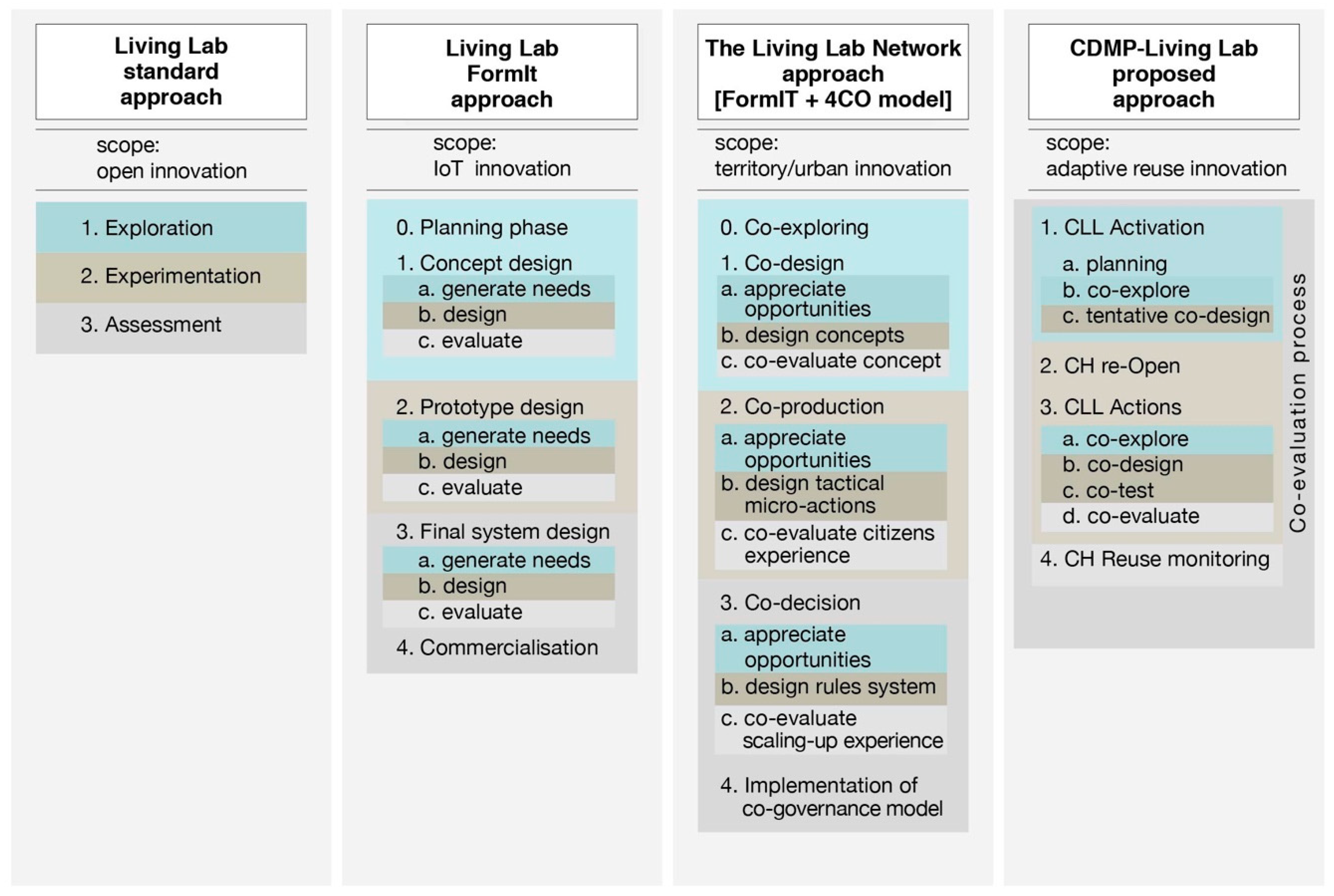

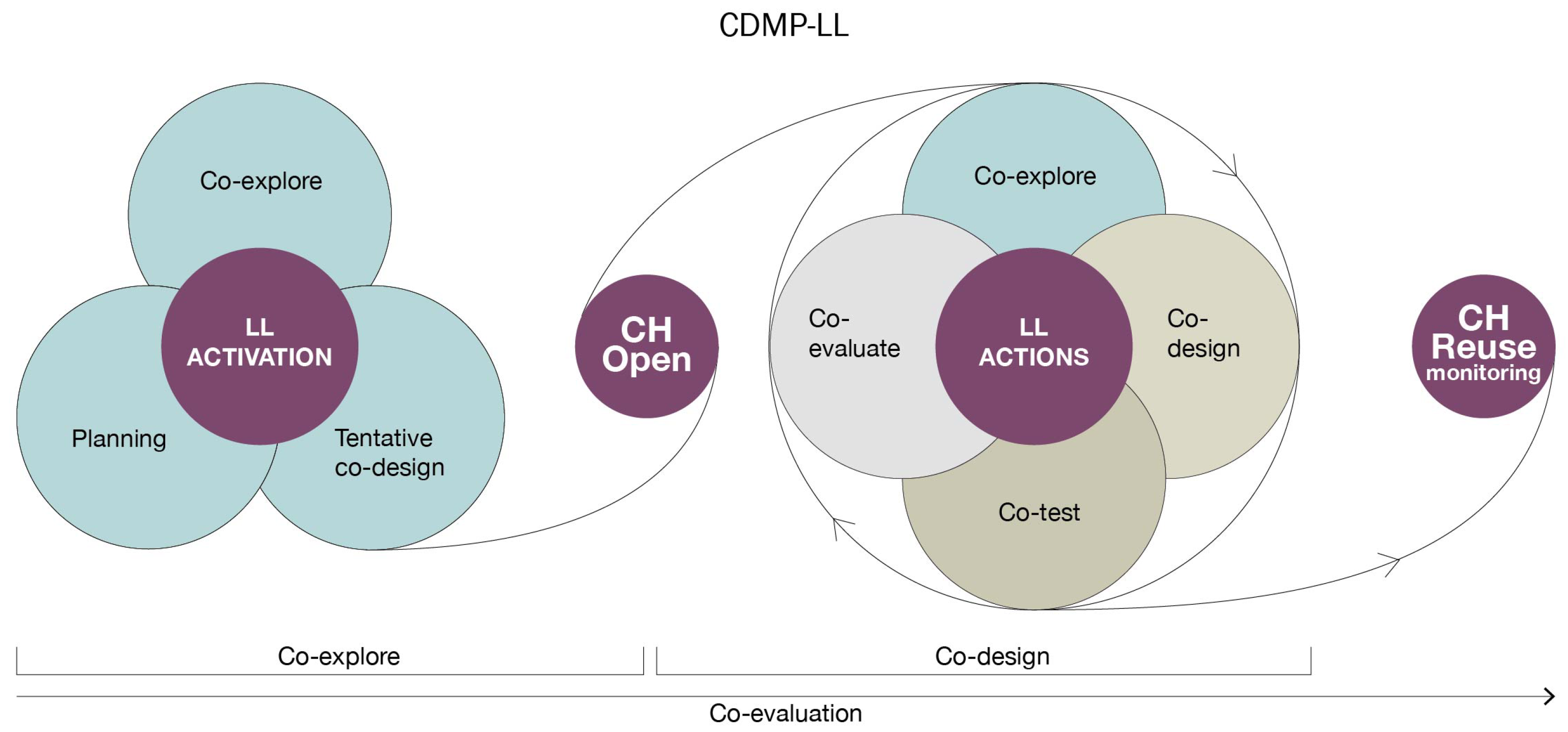

2.1. The Structuring of a Living Lab for Adaptive Reuse Processes

- Exploration of the “current state” of the decision-making context and users to design possible “future states”;

- Experimentation, i.e., co-designing in a real-life context to understand the relationships between the context and the users, triggering new possible behaviors and habits;

- Assessment of impacts by comparing the “current state” and the “future state”.

- CLL activation: the goal is to communicate and involve the community in its activation from the beginning of the open process.

- CH open: the reopening of the abandoned building to the community. This is a real event for the community; this phase highlights that, only after a complex phase of identification of needs and construction of awareness of the values recognized in the CH, is it possible to trigger the conditions for a real change.

- CLL actions: a co-design phase in which the production of different reuse actions is a decisional opportunity [56] to identify and test possible reuses of the cultural good, revealing shared scenarios and producing, at the same time, new forms of social, cultural, and economic capital in the reference context. Each action is characterized by the phases of co-exploration, co-designing, co-testing, and co-evaluation, to include the community in each phase of the process and evaluate each action.

- CH reuse monitoring: the evaluation of the individual actions tested allows identification of the preferred reuse solutions able to make the reuse of the good sustainable over time.

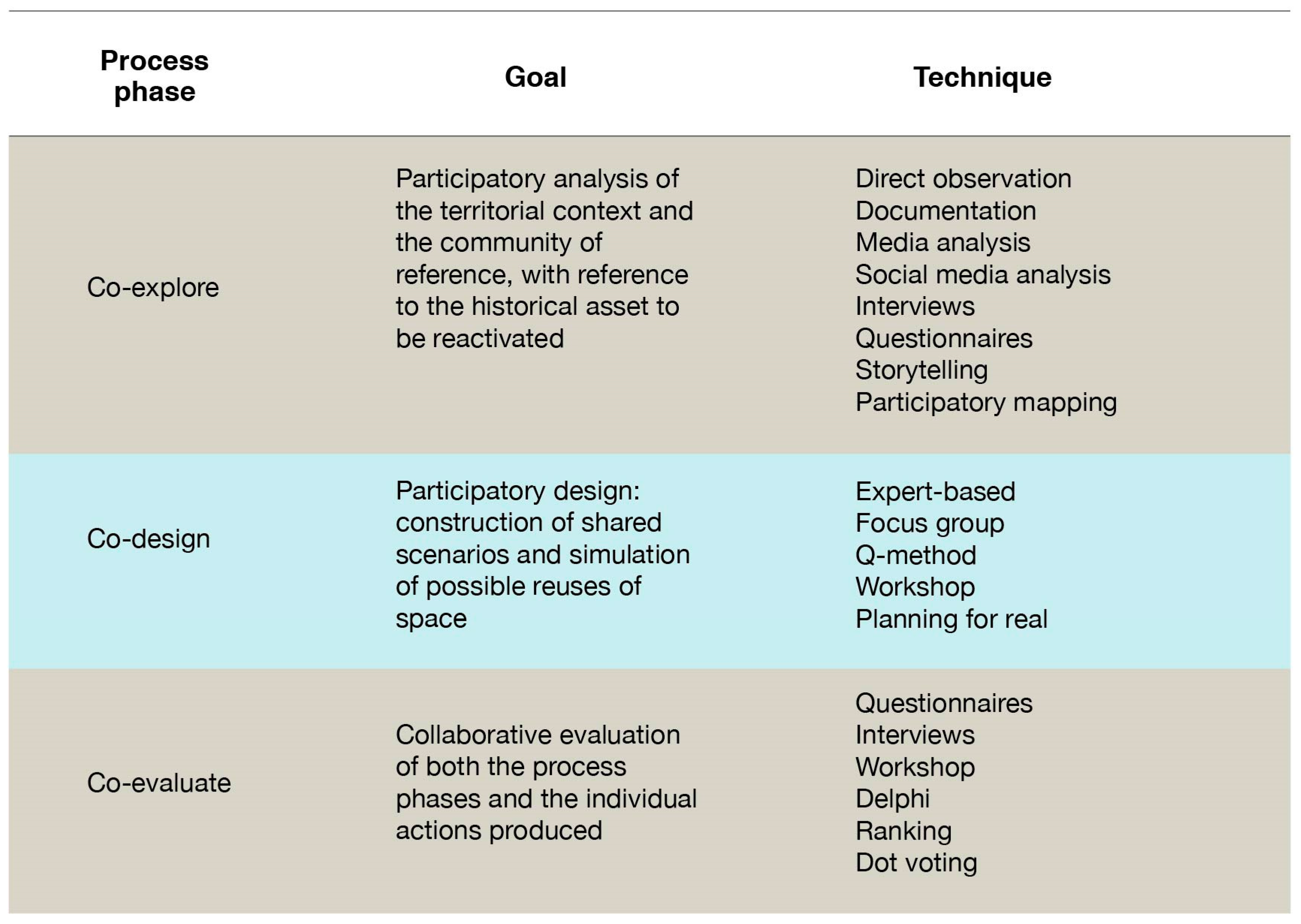

2.2. The Elicitation of Values by Deliberate Valuation Techniques

- Direct observation: human action and behavior reflect social value;

- Documentation: the consultation of textual, photographic, and historical materials reveals information on human preferences concerning the issues addressed;

- Media/social media analysis: the analysis of shared material on the theme or place of interest allows us to obtain data related to the reference values.

2.3. Co-Evaluation in Collaborative Decision-Making Processes

- Development of lists of shared indicators and negotiations between experts and users;

- Individual evaluation of the experience by both experts and users participating in the process, scoring each indicator according to a Likert scale;

- Indicators ranking and comparison between the preferences and contents of the answers, and analyzing the respective attributions of a score;

- Shared indicators verification and, in the case of disagreement, comparison of positions through mutual dialectical observations.

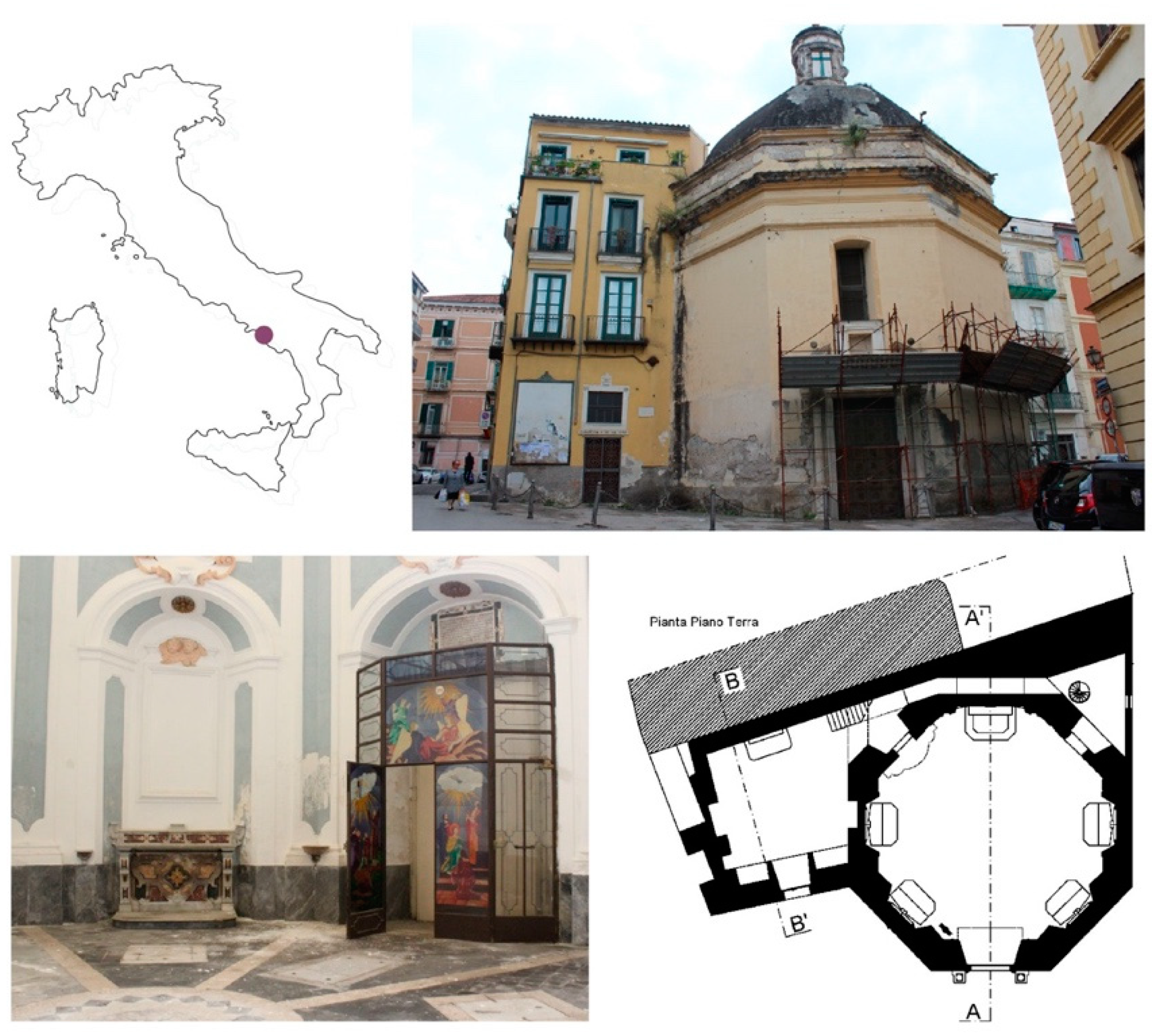

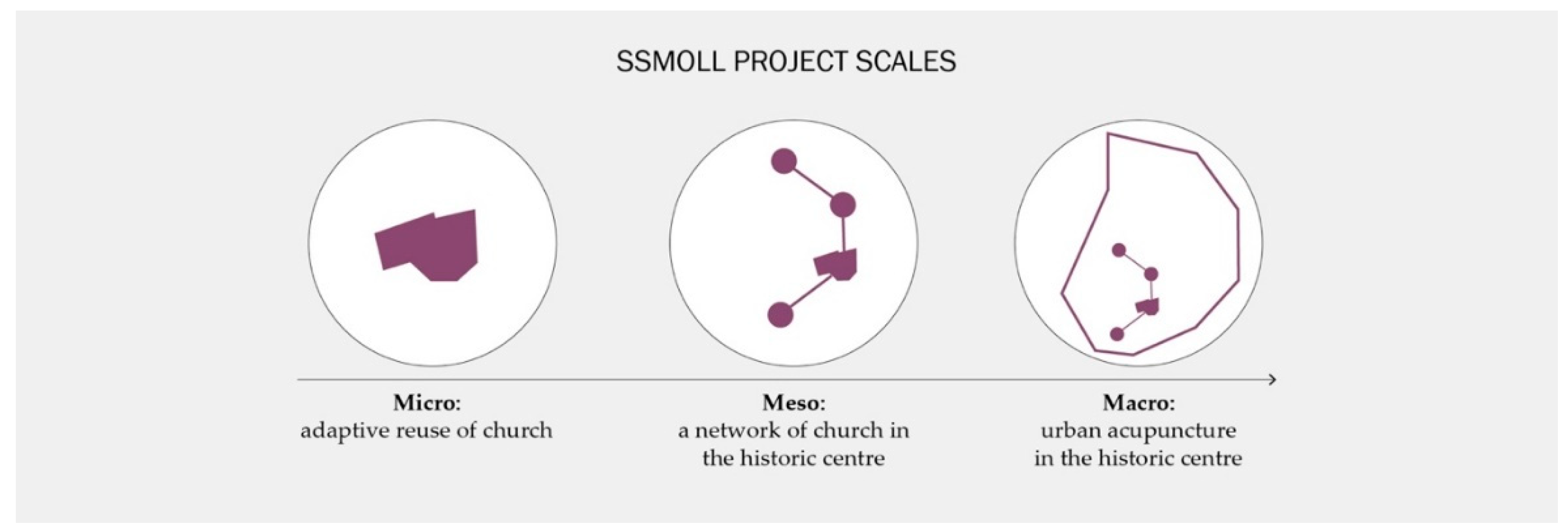

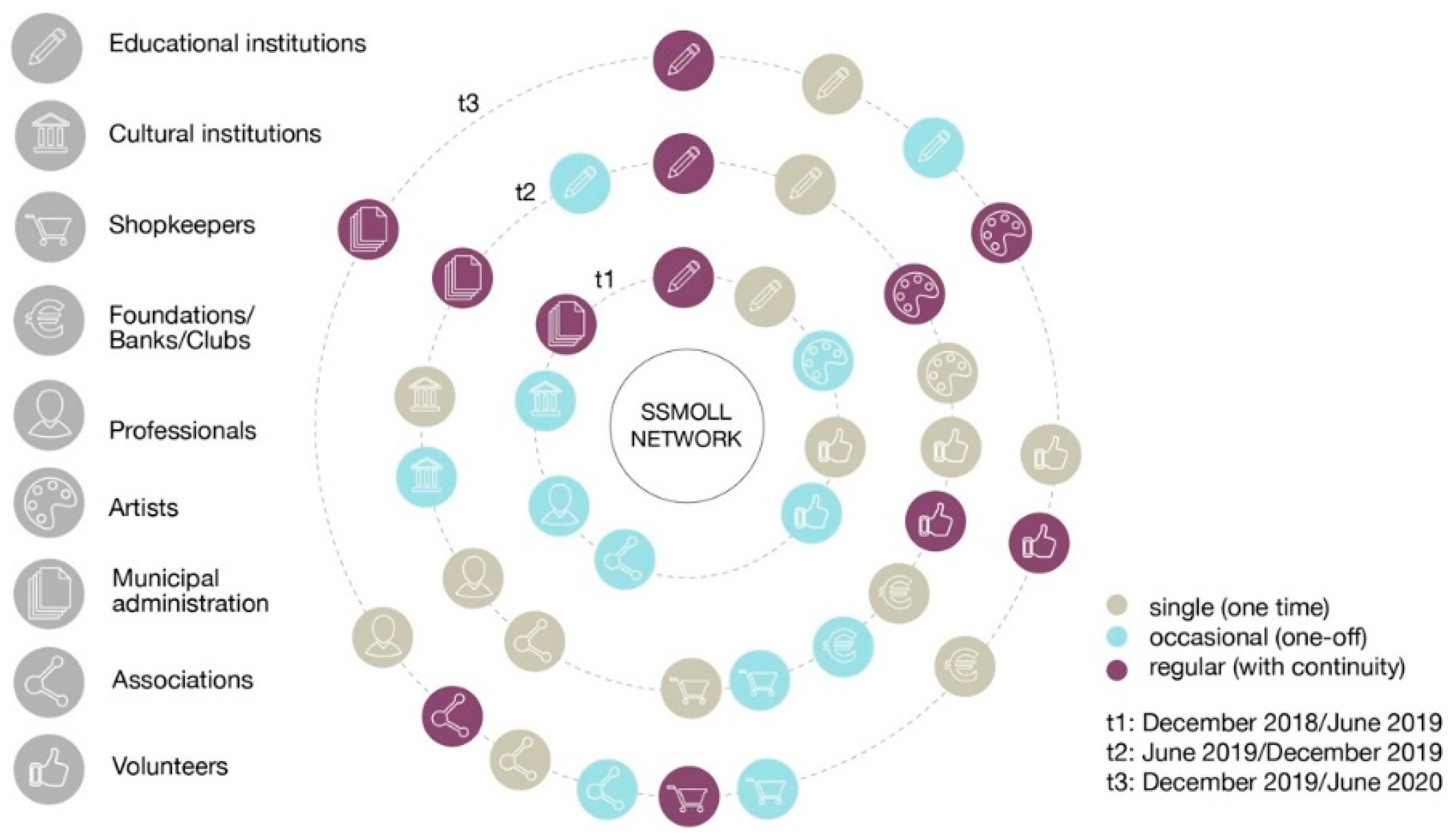

3. The Case Study: The SSMOLL Experiment

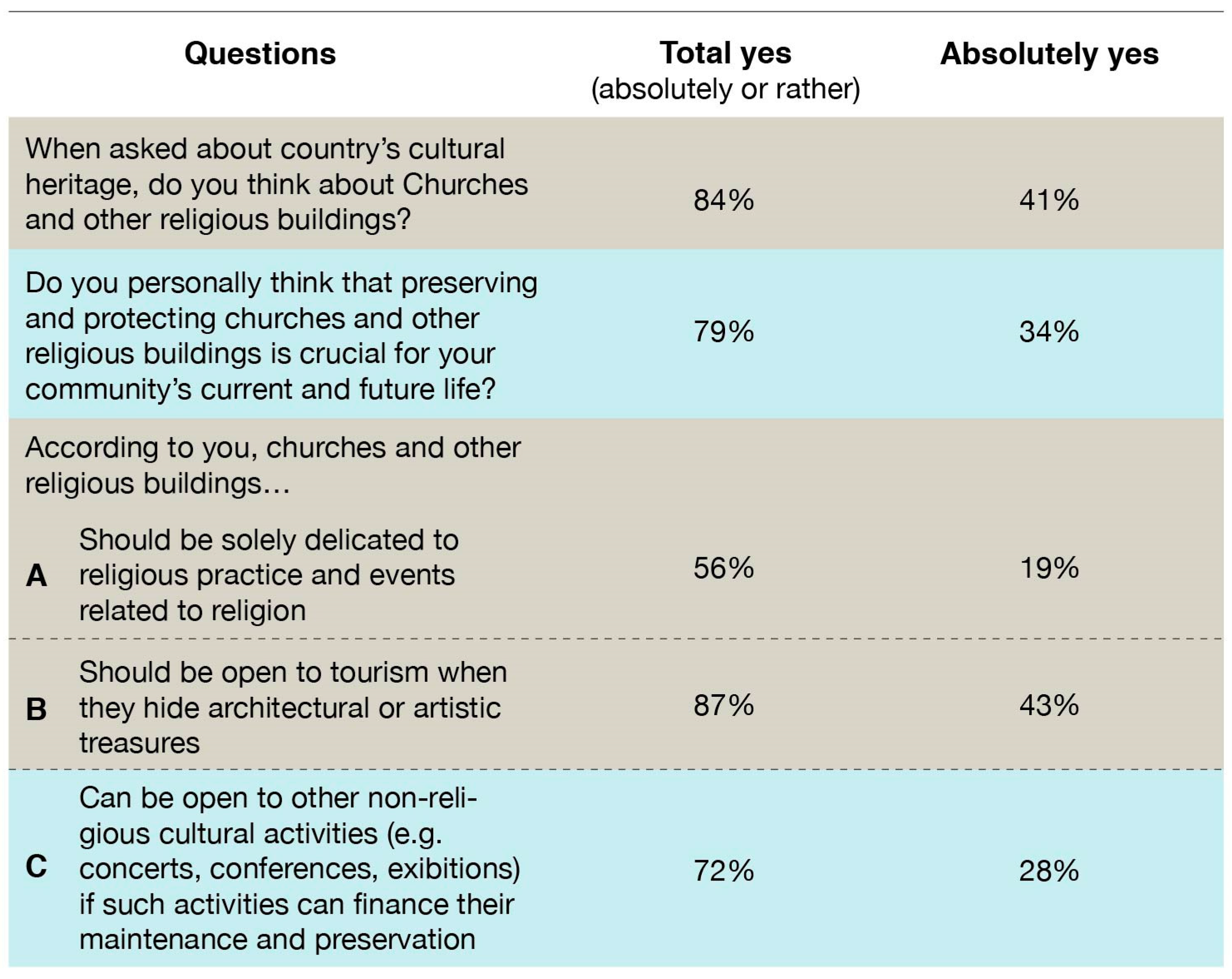

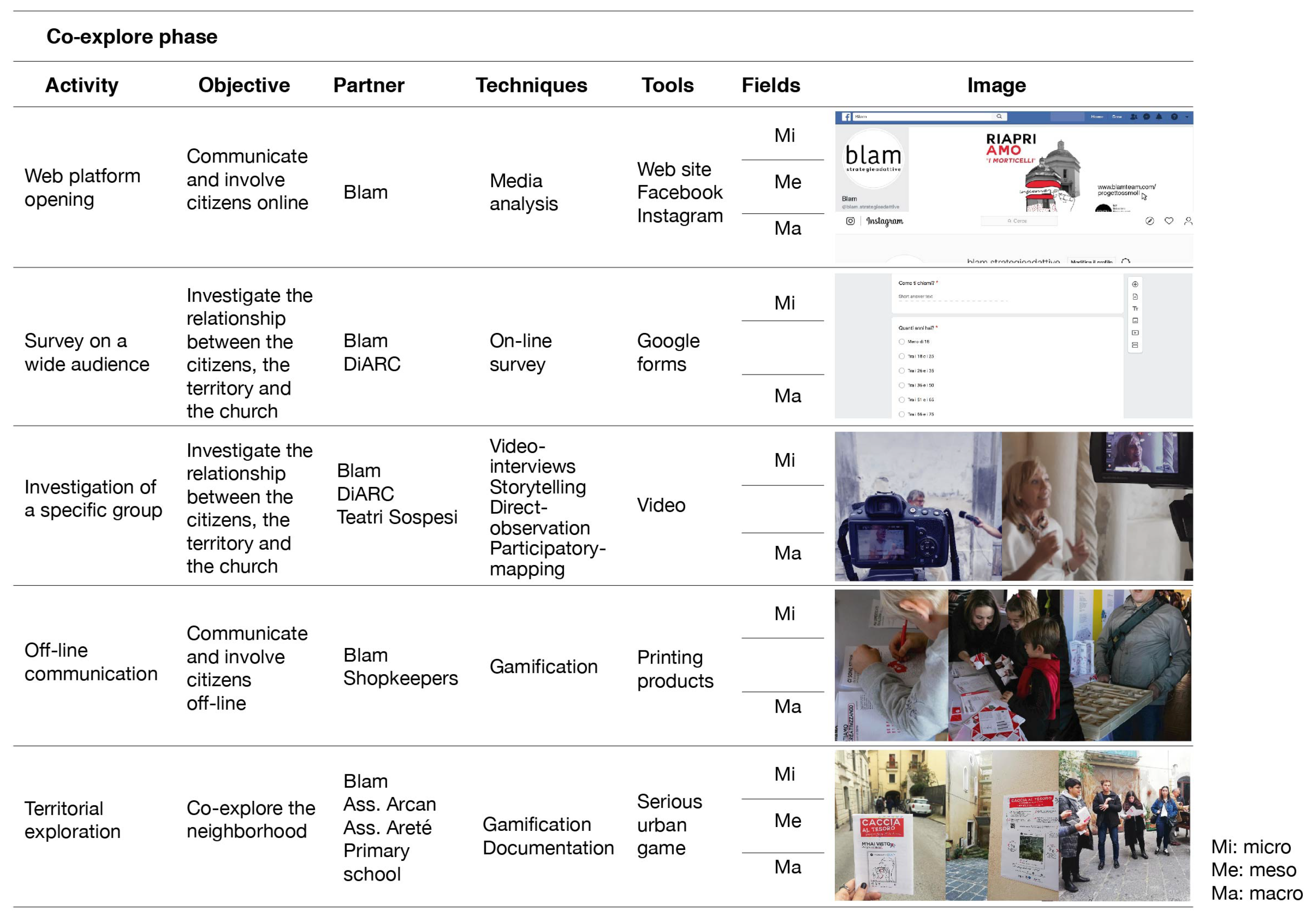

3.1. Co-Explore

- To identify new functions and related values for the use of the CH;

- To build and enhance social and professional networks able to connect people and their territory;

- To activate a more comprehensive process of regeneration of the historical center of Salerno starting from the reuse of the former Morticelli church.

- The relationship with the city of Salerno. Users were asked to define, using the five senses, the potential and criticality of their city;

- The relationship with the former Morticelli church, to gather stories and memories connected to it;

- The visions of a possible reopening and reuse of the church, to identify needs and desires, either latent or explicit.

- “Let’s get to know each other”: informal cognitive phase to collect personal data related to the education and origin of citizens according to the city’s districts;

- “The Salerno you live in”: useful to identify habits and means to frequent the city;

- “Your impressions about Salerno”: A qualitative survey phase on the cultural offerings present in the city, to determine the degree of satisfaction of users expressed on a scale from 1 to 5;

- “How much do you know the Morticelli”: to explore the degree of knowledge about the abandoned space;

- “The idea”: A phase in which the user was presented with a set of possible reuses of the historical building to choose from on a scale from 1 to 5;

- “How can we collaborate”: the last step of the questionnaire focused on the in-depth knowledge of the users, their habits, and their willingness to collaborate by donating time, skills, and money.

3.2. Co-Design

- The satisfaction index of the participants using a scale from 1 to 5;

- The average rate of participation in the individual activities;

- The adaptive capacity of the former church to accommodate the different activities tested, expressed on a scale from 1 to 5;

- The willingness to donate and the willingness to pay for each specific activity proposed, expressed on a monetary scale.

- Co-exploration, in which the participants (students, artists, residents, etc.) co-produce material of knowledge about the Morticelli church and the surrounding urban fabric through interviews, video-interviews, urban explorations, and brainstorming;

- Co-design, in which all the participants, guided by the Blam collective in moments open to citizens, co-create and co-test possible reuse solutions;

- Co-evaluation, in which the participants give back to the whole community through the work produced on the occasion, through events and meetings, thus stimulating feedback and reactions, and activating modes of interaction through collaborative evaluation.

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guterres, A. Report of the Secretary-General on SDG Progress 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UECOSOSC. Special Edition: Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals; Publication E/2019/68; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, A. The Position of Cultural Heritage in the New Urban Agenda a Preliminary Analysis Prepared for ICOMOS; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe Publ.: Faro, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, E.; Blessi, G.T.; Sacco, P.L.; Buscema, M. The interaction between culture, health and psychological well-being: Data mining from the Italian culture and well-being project. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 13, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacostas, S. Special eurobarometer: European knowledge on economical indicators. In Statistics, Knowledge and Policy 2007: Measuring and Fostering the Progress of Societies; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 177–196. ISBN 978-92-64-04323-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. In Structural Survey; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Perth, Australia, 2011; Volume 29, pp. 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, R.D.F.; Tallon, A.R.; Thomas, C.J. City centre regeneration through residential development: Contributing to sustainability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2407–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantell, S.F. The Adaptive Reuse of Historic Industrial Buildings: Regulation Barriers, Best Practices and Case Studies; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VG, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, D. Creative Re-use of Buildings. Volume 1: Principles and Practice; Donhead Publishing: Dorset, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Smith, J. Designing for Future Building: Adaptive Reuse as a Strategy for Carbon Neutral Cities. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Impacts Responses 2012, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, D. Adapting Buildings for Changing Uses: Guidelines for Change of Use Refurbishment; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 9789419235705. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-J.; Zeng, Z.-T. A multi-objective decision-making process for reuse selection of historic buildings. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. Management strategies for historic towns in Europe. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability: International Frameworks, National and local Governance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Vahtikari, T. Valuing World Heritage Cities; Routledge: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 1317002598. [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly, G.; Vahtikari, T. Innovation in Cultural Heritage: For an Integrated European Research Policy; European Commission Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 9279780190. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, E.; Pellegrini, P. Wasting heritage. The slow abandonment of the Italian Historic Centers. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 31, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamer, A. The values of cultural heritage. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Ilde, R., Anna, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 421–437. ISBN 9780857930996. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, A.; Mignosa, A.; Lyudmila, L. Cultural heritage policies: A comparative perspective. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 37–86. ISBN 9780857930996. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the Circular Economy, Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment. Growth within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wijkman, A.; Skånberg, K. The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society; Club of Rome: Winterthur, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Faro, A.; Miceli, A. Sustainable Strategies for the Adaptive Reuse of Religious Heritage: A Social Opportunity. Buildings 2019, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altraeconomia. Available online: https://altreconomia.it/rigenerazione-partecipata-chiese/ (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Lindblad, H.; Löfgren, E. Religious Buildings in Transition. An International Comparison; University of Gothenburg: Gotheburg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FRH Europe. Available online: https://www.frh-europe.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2014-06-Secular-Europe-backs-religious-heritage-report.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Sterken, S.; Longhi, A.; De Wildt, K. Decommissioning and Reuse of Churches: Research perspectives and challenges. In Dio Non Abita Più Qui? Dismissione di Luoghi di Culto e Gestione Integrata dei Beni Culturali Ecclesiastici; Innocenti Furina, V., Ed.; Artemide Edizione: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 291–307. ISBN 978-88-7575-328-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. Risorse Architettoniche e Culturali: Valutazioni e Strategie di Conservazione; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1987. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Città e del Territorio; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1997; Volume 74, ISBN 8846401824. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Concilio, G.; Monno, V. Making Strategies in Spatial Planning: Knowledge and Values; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 9, ISBN 9048131065. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Giovene di Girasole, E. Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process. Sustainabilty 2020, 12, 9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S.; Cannatella, D. Multidimensional spatial decision-making process: Local shared values in action. In Proceedings of the 12TH International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, ICCSA 2012, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS), Part II, Salvador de Bahia, Brasil, 18–21 June 2012; pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zeleny, M. What is autopoiesis. In Autopoiesis: A Theory of Living Organization; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günçe, K.; Misirlisoy, D. Adaptive reuse of military establishments as museums: Conservation vs. museography. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2014, 143, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- House, E.R.; Howe, K.R. Deliberative democratic evaluation in practice. In Evaluation Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Meer, F.-B.; Edelenbos, J. Evaluation in multi-actor policy processes: Accountability, learning and co-operation. Evaluation 2006, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S. From perceived values to shared values: A multi-stakeholder spatial decision analysis (M-SSDA) for resilient landscapes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S.; Venturi, P.; Rago, S. Valutare l’impatto sociale. La questione della misurazione nelle imprese sociali. Impresa Soc. 2015, 6, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Panaro, S. Landscape Co-Evaluation. Approcci Valutativi Adattivi per la Cocreatività Territoriale e l’innovazione Locale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dochy, F.; Segers, M.; Sluijsmans, D. The use of self-, peer and co-assessment in higher education: A review. Stud. High. Educ. 1999, 24, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Barriopedro, E.; Cuesta-Valiño, P.; Penelas-Leguía, A. Co-evaluation, hetero-evaluation and self-evaluation in the area of marketing and market research. In Proceedings of the Edulearn 18: 10th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technology, Palma, Spain, 2–4 July 2018; pp. 3443–3448. [Google Scholar]

- Tessaro, F. La valutazione dei Processi Formativi; Armando Editore: Rome, Italy, 1997; ISBN 8871447069. [Google Scholar]

- Borri, D.; Concilio, G.; Selicato, F.; Torre, C. Ethical and Moral Reasoning and Dilemmas in Evaluation Processes—Perspectives for Intelligent Agents 1: Accounting for Non-Market Values in Planning Evaluation. In Beyond Benefit Cost Analysis; Routledge: England, UK, 2017; pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P.; Schuurman, D.; Ståhlbröst, A.; Vervoort, K. Living Lab methodology handbook. Zenodo 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENoLL and ENoLL members. Introducing Enoll and Its Living Lab Community; Garcia Robles, A., Hirvikoski, T., Schuurman, D., Stokes, L., Eds.; ENoLL: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Era, C.; Landoni, P. Living Lab: A methodology between user-centred design and participatory design. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. The new way of the future: Small, local, open and connected. Soc. Sp. 2011, 75, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Cultural Planning: An Urban Renaissance? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 1134622481. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P.; Schuurman, D. Living labs: Concepts, tools and cases. Info 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Eriksson, C.I.; Ståhlbröst, A.; Svensson, J. A milieu for innovation: Defining living labs. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Innovation Symposium, New York, NY, USA, 6–9 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, R. Value-focused thinking: A path to creative decisionmaking. Long Range Plann. 1996, 2, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Concilio, G.; Tosoni, I. Innovation Capacity and the City: The Enabling Role of Design; Springer Nature: Cham, Swizerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-00122-3. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.K. Speculations on Weak and Strong Sustainability; CSERGE: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, W.; Drechsler, M. Deliberative multicriteria evaluation. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M.; Comberti, C.; Dunford, R. Valuing cultural ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 545–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.; Fazey, I.; Cooper, R.; Hyde, T.; Kenter, J.O. An evaluation of monetary and non-monetary techniques for assessing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services to people in countries with developing economies. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O.; O’Brien, L.; Hockley, N.; Ravenscroft, N.; Fazey, I.; Irvine, K.N.; Reed, M.S.; Christie, M.; Brady, E.; Bryce, R. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecol. Econ. 2015, 111, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M. Cultural, Creative, Community Hub: Dai valori condivisi ai valori sociali condivisi per la rigenerazione della città storica. In Abitare il Futuro; CLEAN: Napoli, Italy, 2016; pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramstad, W.E.; Tveit, M.S.; Fjellstad, W.J.; Fry, G.L.A. Relationships between visual landscape preferences and map-based indicators of landscape structure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Carmona, A.; Lozada, P.; Jaramillo, A.; Aguayo, M. Mapping recreation and ecotourism as a cultural ecosystem service: An application at the local level in Southern Chile. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 40, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.J.; Nicholas, K.A. More than wine: Cultural ecosystem services in vineyard landscapes in England and California. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 124, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.L. Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior; Mouton & Co.: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1954; ISBN 3111657159. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. Creative evaluations for a human sustainable planning. In Making Strategies in Spatial Planning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Poli, G. A complex values map of marginal urban landscapes: An experiment in Naples (Italy). Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inf. Syst. 2013, 4, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, F. Modelli e Pratiche di Valutazione: Dall’osservazione alla Verifica. Lab. Univ. RED–SSIS Veneto 2005. Available online: http//www.univirtual.it/red/files/file/TessaroModelliPraticheValutaz.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2016).

- Tessaro, F. I fondamenti della valutazione scolastica. Lab. Univ. RED–SSIS Veneto AA 2004, 2005, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Zamagni, S. Teoria Economica e Relazioni Interpersonali; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2006; ISBN 8815114327. [Google Scholar]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Forbici, S. Power to the people: When culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G. Cities as creative hubs: From the instrumental to the functional value of culture-led local development. In Sustainable City and Creativity: Promoting Creative Urban Initiatives; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2012; pp. 245–270. [Google Scholar]

- Latonero, M.; Shklovski, I. Emergency management, Twitter, and social media evangelism. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Cris. Response Manag. 2011, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppock, P.J.; Ferri, G. Serious urban games: From play in the city to play for the city. In Media and the City: Urbanism, Technology and Communication; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2013; pp. 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal, J. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 1101475498. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Reitano, M. Community-led processes for peri-urban regeneration in Naples: Evaluating scenarios of social self-organisation and cooperation. BDC Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini. 2019, 19, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Diappi, L. Adaptive Evaluations in Complex Contexts: Introduction. Sci. Reg. 2014, 1, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Adaptive sustainable reuse for cultural heritage: A multiple criteria decision aiding approach supporting urban development processes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Gagliano, F.; Giannitrapani, E.; Marisca, C.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Promoting Research and Landscape Experience in the Management of the Archaeological Networks. A Project-Valuation Experiment in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; D’Alpaos, C.; Marello, A. An Application of the A’WOT Analysis for the Management of Cultural Heritage Assets: The Case of the Historical Farmhouses in the Aglié Castl (Turin). Sustainability 2020, 12, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F.; Del Giudice, V.; De Paola, P.; Troisi, F. Valuation of the Vocationality of Cultural Heritage: The Vesuvian Villas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldanise, G. From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S. I luoghi dell’economia civile per lo sviluppo sostenibile. In Da Spazi a Luoghi. Proposte per una Nuova Ecologia dello Sviluppo; AICCON: Forlì, Italia, 2017; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerreta, M.; Elefante, A.; La Rocca, L. A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410561

Cerreta M, Elefante A, La Rocca L. A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410561

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerreta, Maria, Alessia Elefante, and Ludovica La Rocca. 2020. "A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410561

APA StyleCerreta, M., Elefante, A., & La Rocca, L. (2020). A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project. Sustainability, 12(24), 10561. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410561