Sustainability of Cluster Organizations as Open Innovation Intermediaries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Methods and Sample

3.2. Analytic Procedure

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of Interizon

4.2. Practices of Open Innovation in Interizon

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalby, S. Climate Change, Security and Sustainability. In Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Global Governance Challenges; Dalby, S., Horton, S., Mahon, R., Thomaz, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, a New ERA for Research and Innovation; COM/628 Final; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, F.; Rogge, K.S.; Howlett, M. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: New approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open innovation and its effects on economic and sustainability innovation performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Henneberg, S.C.; Ivens, B.S. Open sustainability: Conceptualization and considerations. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Zobel, A.-K.; Afuah, A.; Almirall, E.; Brunswicker, S.; Dahlander, L.; Frederiksen, L.; Gawer, A.; Gruber, M.; Haefliger, S.; et al. The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 8–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ding, X.-H.; Wu, S. Exploring the domain of open innovation: Bibliometric and content analyses. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckel, A.; Veilleux, S.; Dana, L.P. Local Open Innovation: A means for public policy to increase collaboration for innovation in SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 153, 119891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalicchio, A.; Ardito, L.; Savino, T.; Albino, V. Managing knowledge assets for open innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, V.; Täube, F.A.; Heidenreich, S.; Bogers, M. Establishing open innovation culture in cluster initiatives: The role of trust and information asymmetry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, S.; Ayerbe, C.; Dubouloz, S.; Robert, M.; West, J. Managerial Innovation and Management of Open Innovation. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2020, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Salter, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: The next decade. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovuakporie, O.D.; Pillai, K.G.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Differential moderating effects of strategic and operational reconfiguration on the relationship between open innovation practices and innovation performance. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdad, M.; De Marco, C.E.; Piccaluga, A.; Di Minin, A. Harnessing adaptive capacity to close the pandora’s box of open innovation. Ind. Innov. 2020, 27, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M. How open is innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Ramos, I. Open Innovation in SMEs: From Closed Boundaries to Networked Paradigm. Issues Inf. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2010, 7, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Open Innovation 2.0 Yearbook 2017–2018. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/10defd18-d291-11e8-9424-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- McPhillips, M. Innovation by proxy–clusters as ecosystems facilitating open innovation. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2020, 16, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. On Competition; Harvard Business School Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. “Mode 3” and “Quadruple Helix”: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 46, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lämmer-Gamp, T.; zu Köcker, G.M.; Nerger, M. Cluster Collaboration and Business Support Tools to Facilitate Entrepreneurship, Cross-Sectoral Collaboration and Growth. 2014. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/9972 (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Shearmur, R.; Doloreux, D. How open innovation processes vary between urban and remote environments: Slow innovators, market-sourced information and frequency of interaction. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M. The co-location of innovation and production in clusters. Ind. Innov. 2020, 27, 842–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotz, M. Cluster role in industry 4.0—A pilot study from Germany. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2020. (Issue ahead-of-print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, C.E.; Martelli, I.; Di Minin, A. European SMEs’ engagement in open innovation When the important thing is to win and not just to participate, what should innovation policy do? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 152, 119843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Y.; He, B.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L. Network embeddedness and inbound open innovation practice: The moderating role of technology cluster. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knockaert, M.; Spithoven, A.; Clarysse, B. The impact of technology intermediaries on firm cognitive capacity additionality. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 81, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Howells, J.; Meyer, M. Innovation intermediaries and collaboration: Knowledge–based practices and internal value creation. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziwon, A.; Bogers, M. Open innovation in SMEs: Exploring inter-organizational relationships in an ecosystem. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edler, J.; Yeow, J. Connecting demand and supply: The role of intermediation in public procurement of innovation. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedlund, A. The roles of intermediaries in a regional knowledge system. J. Intellect. Cap. 2006, 7, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, K.; Wilden, R.; Gudergan, S. Open Service Innovation: The Role of Intermediary Capabilities. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 808–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agogué, M.; Berthet, E.; Fredberg, T.; Le Masson, P.; Segrestin, B.; Stoetzel, M.; Wiener, M.; Yström, A. Explicating the role of innovation intermediaries in the “unknown”: A contingency approach. J. Strategy Manag. 2017, 10, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkina, E.; Oreshkin, B.; Kali, R. Regional innovation clusters and firm innovation performance: An interactionist approach. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, B.; Götz, M. Internationalization intensity of clusters and their impact on firm internationalization: The case of Poland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 958–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velt, H.; Torkkeli, L.; Laine, I. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Research: Bibliometric Mapping of the Domain. J. Bus. Ecosyst. 2020, 1, 43–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Thomas, L. Innovation ecosystems. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 204–288. [Google Scholar]

- Asplund, F.; Björk, J.; Magnusson, M.; Patrick, A.J. The genesis of public-private innovation ecosystems: Bias and challenges. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Maas, G. Innovation and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems as Important Building Blocks. In Transformational Entrepreneurship Practices; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R.; Kapoor, R. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Kim, J.-W. Integrating Suppliers into Green Product Innovation Development: An Empirical Case Study in the Semiconductor Industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.M. Współpraca w Inicjatywach Klastrowych. Rola Bliskości w Rozwoju Powiązań Kooperacyjnych [Cooperation in Cluster Initiatives: The Role of Proximity in the Development of Cooperative Relationships]; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdanskiej: Gdansk, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, A.M. The significance of proximity in cluster initiatives. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2019, 29, 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Works; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967; Available online: http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Benchmarking klastrów w Polsce—2010. Raport z badania [Cluster Benchmarking in Poland—2010. Research Report]. Available online: https://www.parp.gov.pl/images/sites/ClusterFY/Benchmarking_klastrow_w_Polsce_-_2010.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Hołub-Iwan, J. (Ed.) Benchmarking klastrów w Polsce—Edycja 2012; Raport z Badania; PARP: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Plawgo, B. Benchmarking klastrów w Polsce—Edycja 2014; Raport z badania; PARP: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, M.P.V.; Sverrisson, Á. Enterprise clusters in developing countries: Mechanisms of transition and stagnation. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2003, 15, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouder, R.; John, C.H.S. Hot spots and blind spots: Geographical clusters of firms and innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 1192–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, A.; Hauge, E. Regional clusters in Europe. Obs. Eur. Smes 2002, 3, 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, S.A. Creating Smart Systems: A Guide to Cluster Strategies in Less Favoured Regions; Regional Technology Strategies: Carrboro, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sonderegger, P.; Täube, F. Cluster life cycle and diaspora effects: Evidence from the Indian IT cluster in Bangalore. J. Int. Manag. 2010, 16, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sölvell, Ö.; Lindqvist, G.; Ketels, C. The Cluster Initiative Greenbook; Ivory Tower: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, G.; Ketels, C.; Sölvell, Ö. The Cluster Initiative Greenbook 2.0; Ivory Tower: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Promoting Entrepreneurship and Innovative SMEs in a Global Economy. 2004. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/31919590.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Giuliani, E. Networks and heterogeneous performance of cluster firms. In Applied Evolutionary Economics and Economic Geography; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Radziwon, A.; Bogers, M.; Bilberg, A. Managing Open Innovation across SMEs: The Case of a Regional Ecosystem. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014, 2014, 11740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepelski, D.; Van Roy, V.; Pesole, A. The organisational and geographic diversity and innovation potential of EU-funded research networks. J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Brown, R. Exploratory Techniques for Examining Cluster Dynamics: A Systems Thinking Approach. Local Econ. 2009, 24, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes Versus Network Closure as Social Capital. In Social Capital: Theory and Research; Lin, N., Cook, K., Burt, R.S., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Duysters, G.; Lokshin, B. Determinants of alliance portfolio complexity and its effect on innovative performance of companies. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthinier-Poncet, A.; Cluster Governance and Institutional Dynamics. A Comparative Analysis of French Regional Clusters of Innovation. Available online: https://emnet.univie.ac.at/uploads/media/Berthinier_Poncet.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

| No. | Category | Peculiarities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cooperation levels |

|

| 2 | Open innovation practices |

|

| 3 | The strength of relationships |

|

| 4 | Type of information and knowledge |

|

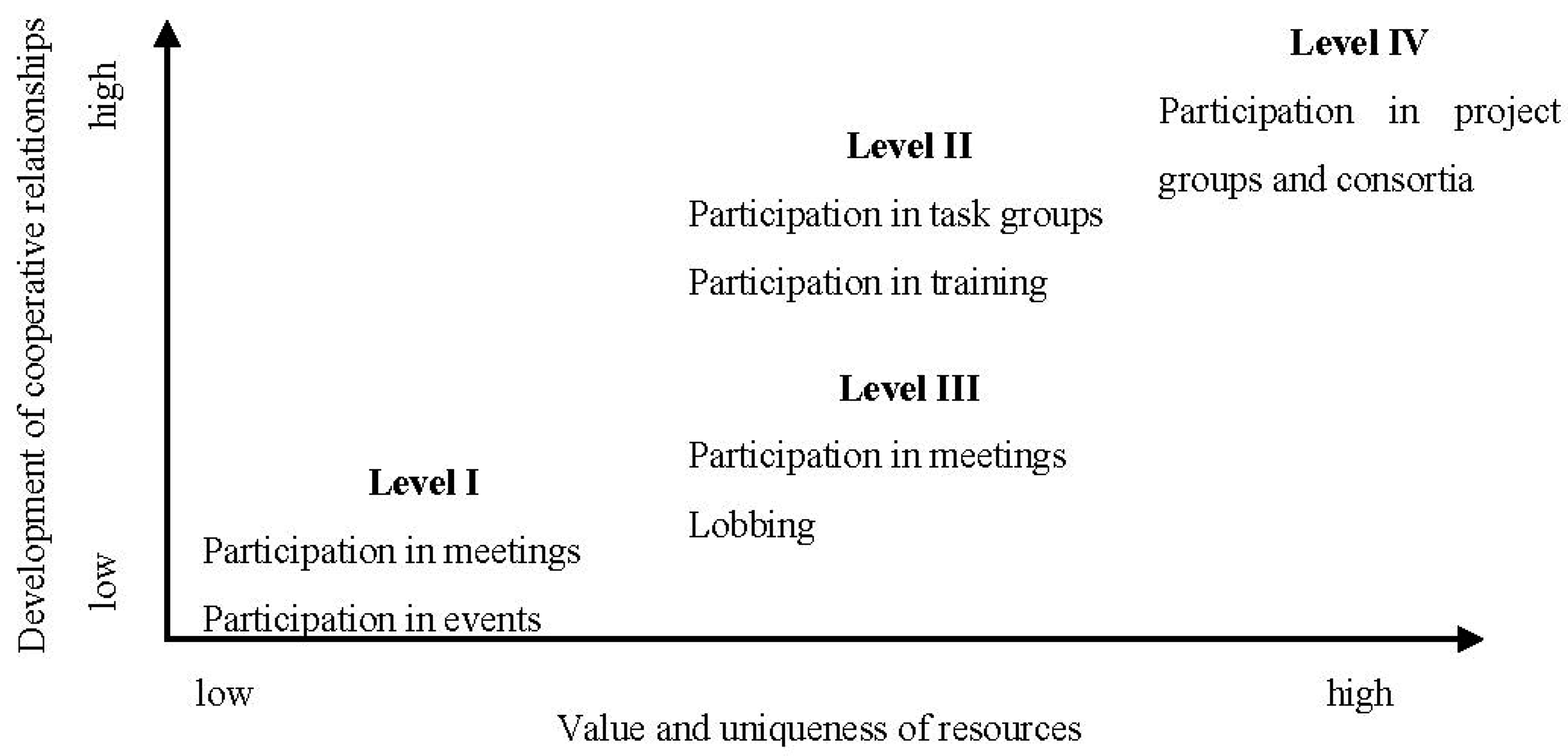

| Category 1. Cooperation Levels (CLs) | Category 2. Open Innovation Practices (OIPs) | Category 3. The Strength of Relationships (SRs) | Category 4. Type of Information and Knowledge (I&K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level I “Integration at the unit level” |

|

|

|

| Level II “Allocation and integration at the process level” |

|

|

|

| Level III “Impact on the environment” |

|

|

|

| Level IV “Creation and integration at the organizational level” |

|

|

|

| (CL) | (OIP) | (SR) | Selected Quotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| I |

| Establishing contact | “The participants start to meet in the cluster, talk, discuss—relationships develop. Such a level of trust is very underestimated.” (R1) |

| II |

| Development of relationships | “I was at several such meetings and I found out that when a person shares, others also share with him and then the cooperation evolves different.” (R6) |

| III |

| Development of relationships with external partners (outside CO) | “The cluster is like a bridge: we connect companies with specific scientists, we get them to meet, so that various things at the university are easier to implement.” (R2) |

| IV |

| Trust development and verification | “We like each other and we trust each other, because we have completed a project together. We have one or two partners, now the third is being ready with whom we are able to cooperate. We have already come to the conclusion that we simply cannot afford to experiment with that.” (R9) |

| (OIP) | (I&K) | Selected Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in meetings | General information | “Information… I think that’s not about newsletters, but off-the-record discussions. In a place where people can meet and discuss different subjects and, following multiple meetings, share unofficial knowledge on different topics—that’s where a cluster is helpful for sure. People find out what is happening on the market, find out about the introduction of new rules and regulations, or perhaps new requirements—unofficial news. That’s what’s not included in the newsletter.” (R7) |

| Participation in events | “Internal promotion is an important aspect of our cluster. We show which companies managed to gain specific benefits—we show success stories. Share specifics that companies want to speak about. For instance, we have this event called ICT Day, which takes on a different form each year, but which is organized annually. It was interesting for companies to see their counterparts publicly speak about their success stories. Because that’s living proof that clusters may be more beneficial to their members. Companies may learn more about one another.” (R4) |

| (OIP) | (I&K) | Selected Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in task groups | Detailed information | “This industry is so extensive, knowledge is so vast that it cannot be fully understood. Therefore, it is imperative to choose the appropriate thematic threads and someone has to do it for someone to cede. It is best for companies that hope to develop their business in specific directions and will dig.” (R10) |

| Participation in training | “The exchange of resources—is very, very much present within human capital. We have a foundation which is tasked with personnel training, where this phenomenon is present to a large degree. Mutual teaching about project management, mutual teaching of programming languages […] training sessions, mutual workshops, we had numerous such sessions where people would teach one another.” (R1) |

| (OIP) | (I&K) | Selected Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Lobbing | Significant information about the socio-economic environment | “We have contact with the local administration and the central authorities, we participate in different assemblies, we have our representative in the committee monitoring the Ombudsman and in the National Centre for Research and Development. Whenever there is a committee in the Sejm which deals with clustering, one of our members participates in its meetings.” (R2) |

| Participation in meetings (with entities from outside CO) | “The involved cluster members first learn about the created, emerging consortia for projects from the European Commission, from large grants.” (R1) |

| (OIP) | (I&K) | Selected Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in project groups and consortia | Confidential information New knowledge | “Knowledge arises in projects. Some of the documents are open to everyone, part only for people who have carried out these projects.” (R5) |

| Participation in teams focused on the development of permanent cooperation | “We like each other and we trust each other because we have completed one project together. We have one, two partners, now the third one is joining, with whom we are able to cooperate. (…) Thanks to that we are able to trust each other, exchange information, talk about new possibilities”. (R9) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lis, A.M.; McPhillips, M.; Lis, A. Sustainability of Cluster Organizations as Open Innovation Intermediaries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410520

Lis AM, McPhillips M, Lis A. Sustainability of Cluster Organizations as Open Innovation Intermediaries. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410520

Chicago/Turabian StyleLis, Anna Maria, Marita McPhillips, and Adrian Lis. 2020. "Sustainability of Cluster Organizations as Open Innovation Intermediaries" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410520

APA StyleLis, A. M., McPhillips, M., & Lis, A. (2020). Sustainability of Cluster Organizations as Open Innovation Intermediaries. Sustainability, 12(24), 10520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410520