Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

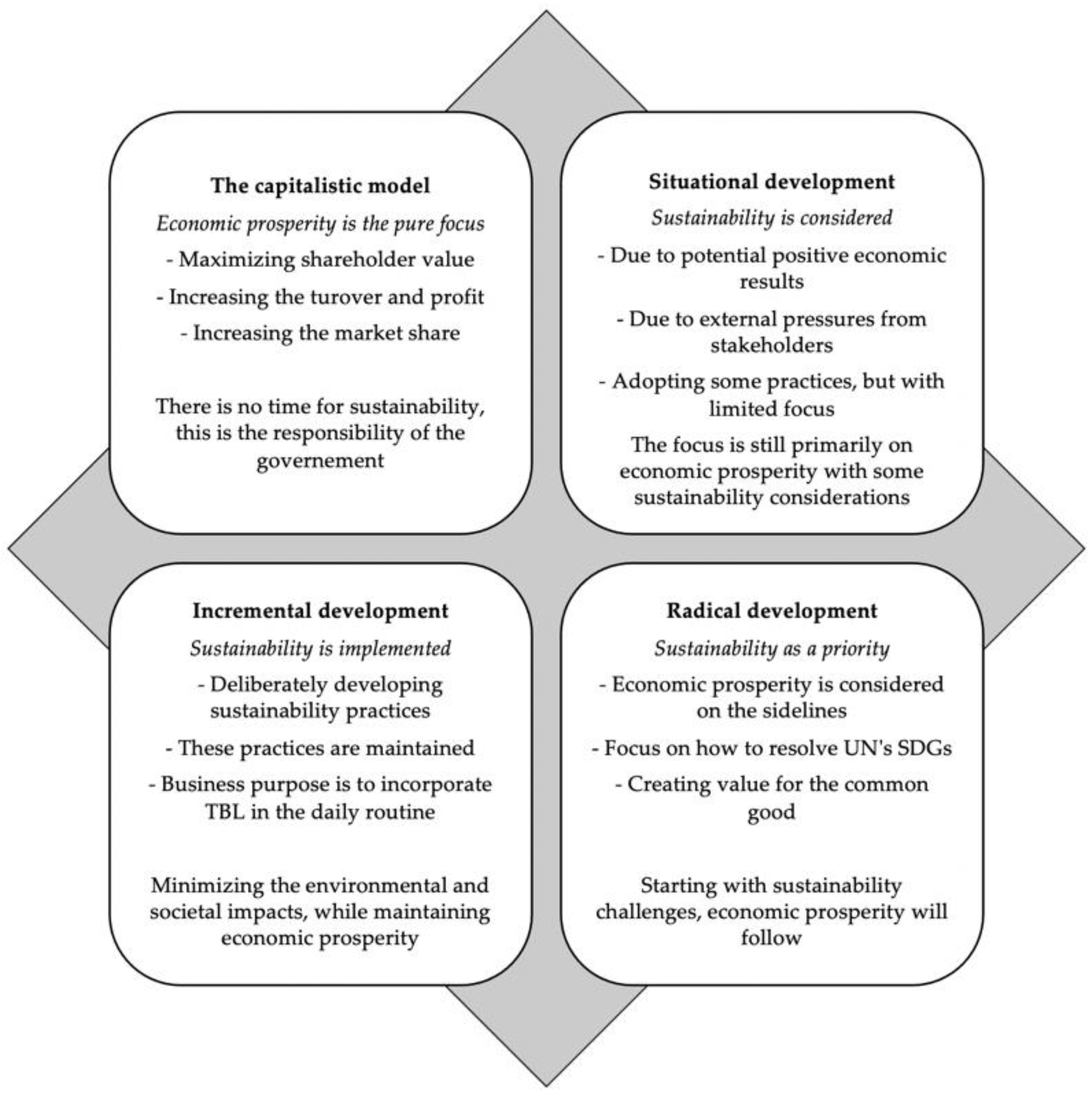

2.1. Defining Sustainability

2.2. Defining Sustainability Practices

2.3. Drivers for Sustainable Development

2.3.1. External Factors

Government

Networks and Alliances

Competitors

Suppliers

Customers

Community Surroundings

2.3.2. Internal Factors

Employees

Organizational Culture

Brand Image and Reputation

Competitive Advantages and Strategic Intent

Size of the Firm

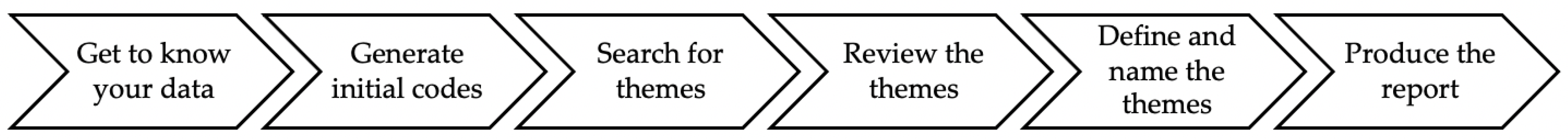

3. Methods

4. Findings and Discussion

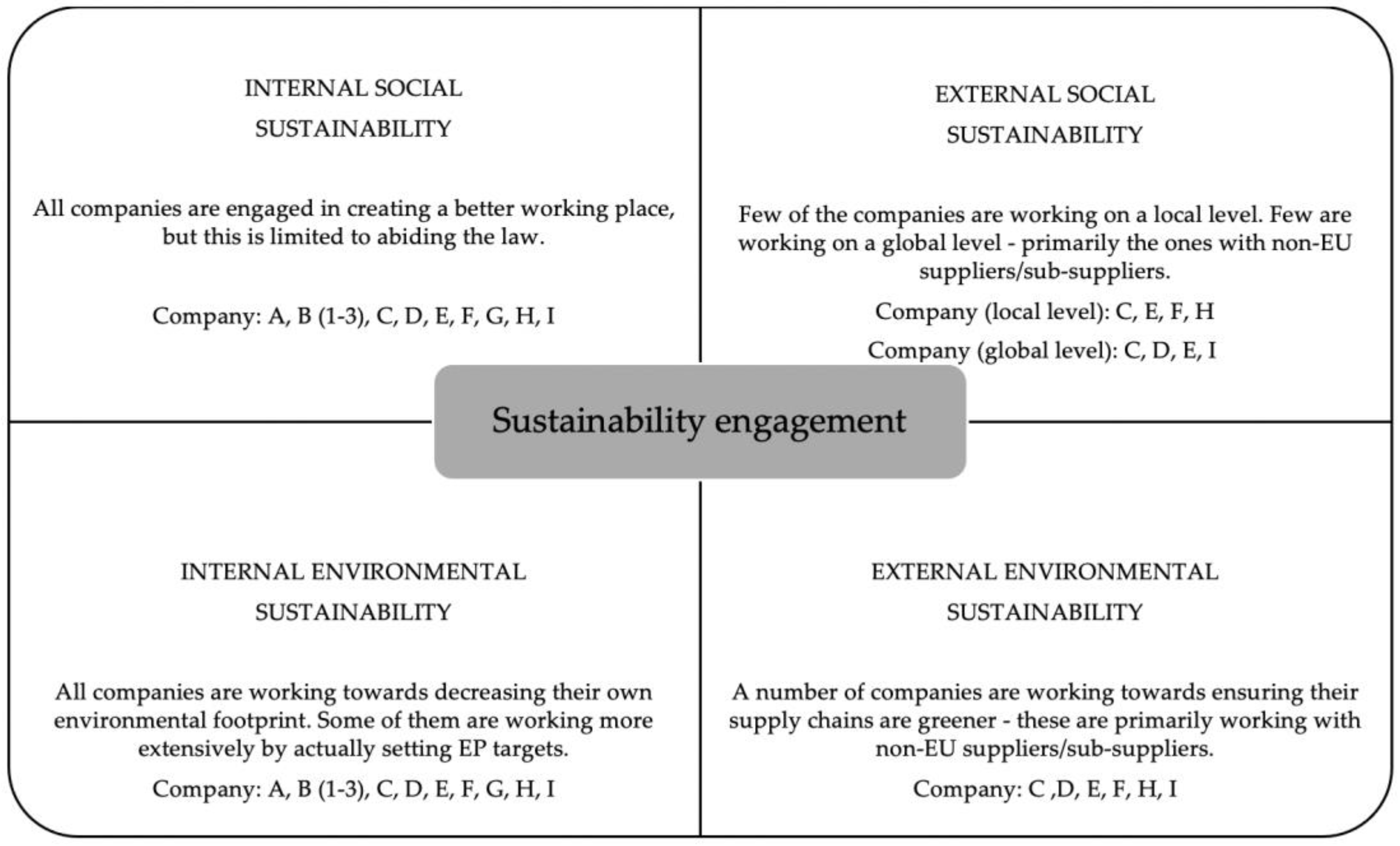

4.1. The Participating SMEs’ Perception of Sustainability Engagement

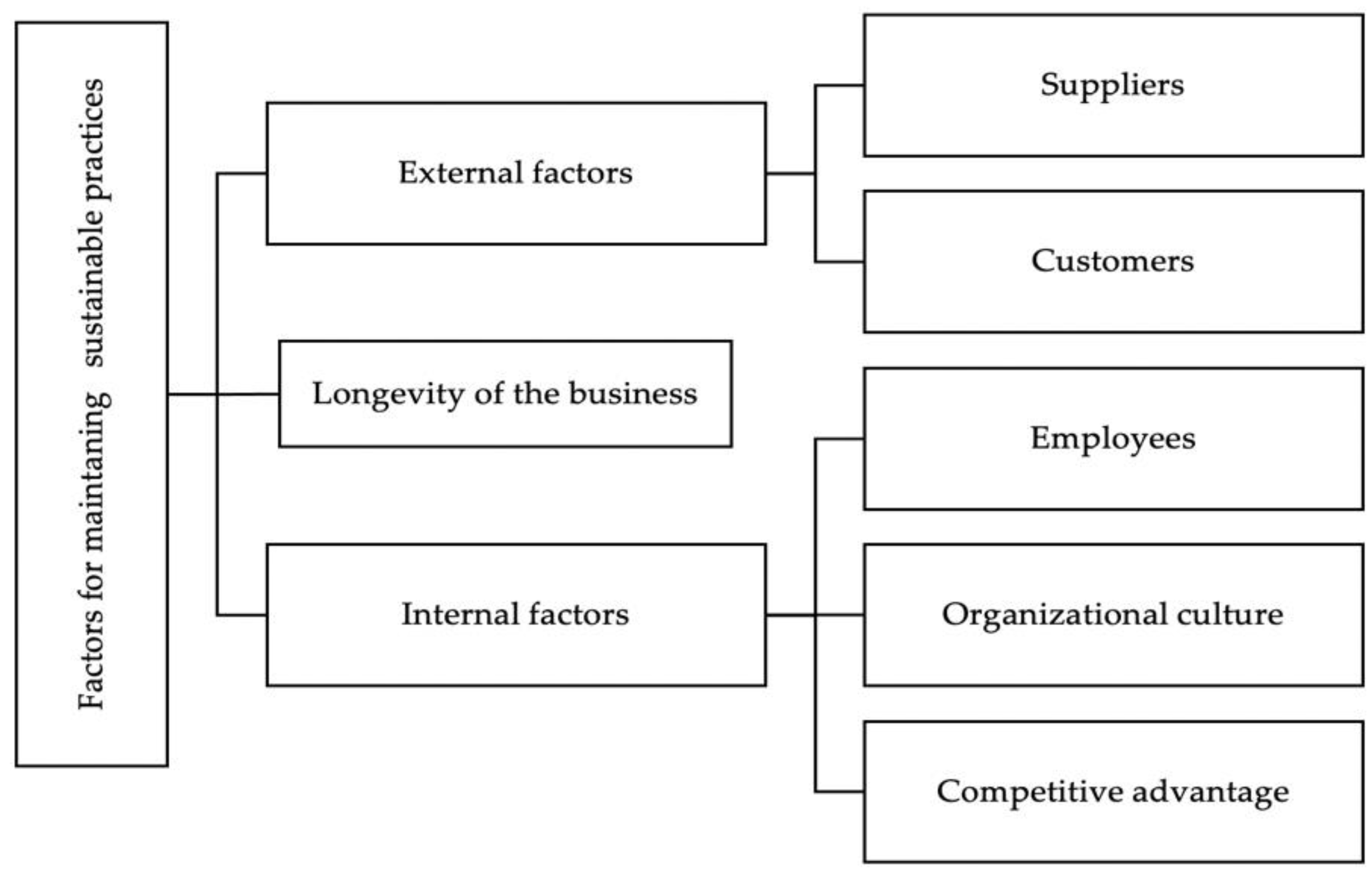

4.2. Drivers for Sustainable Development

4.2.1. External Factors

Government

Networks and Alliances

Competitors

Suppliers

Customers

Community Surroundings

4.2.2. Internal Factors

Employees

Organizational Culture

Brand Image and Reputation

Competitive Advantage and Strategic Intent

Size of the Firm

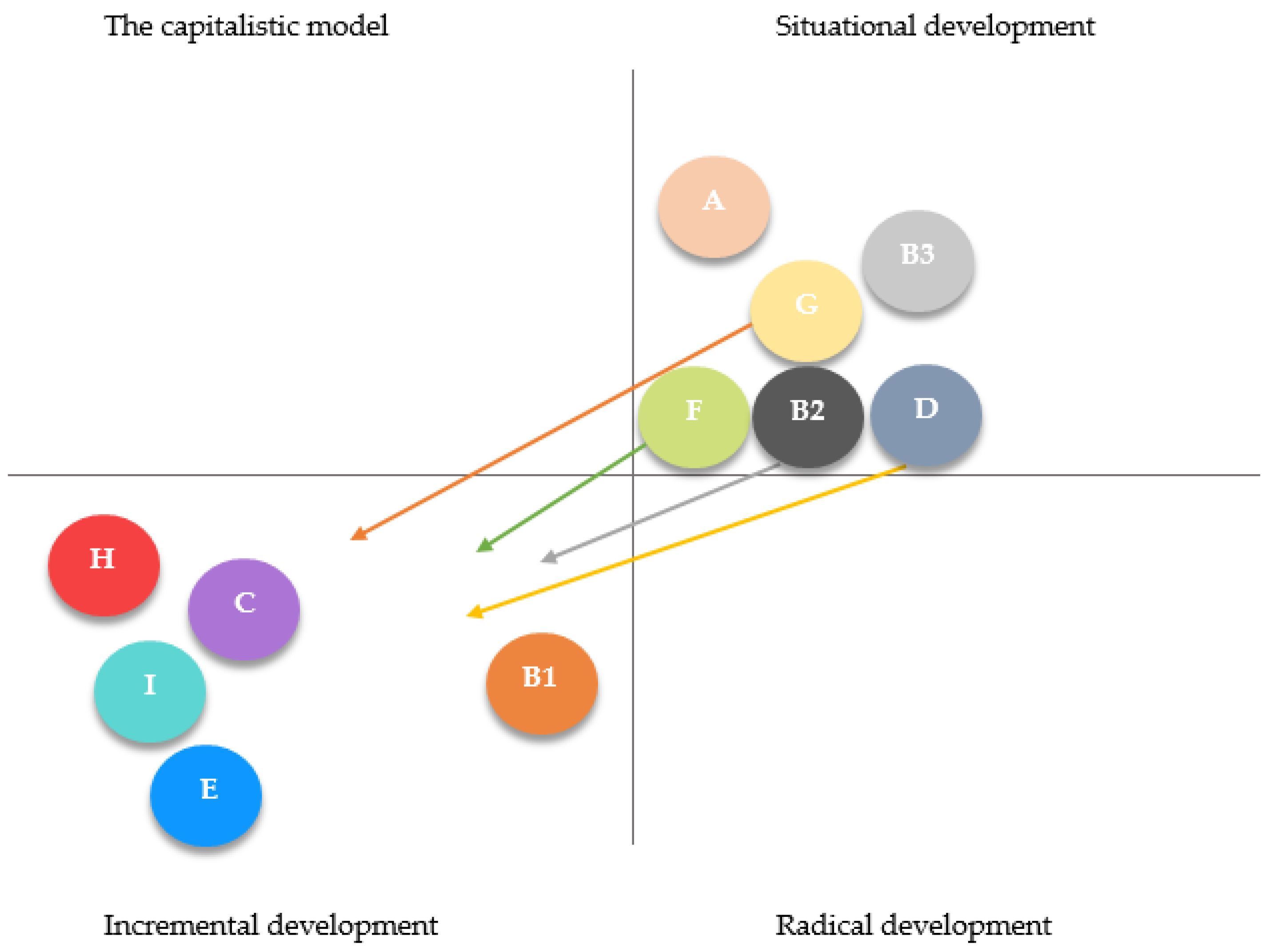

4.3. Progress of Business Sustainability Practices

4.3.1. Company A

4.3.2. Company B

4.3.3. Company C

4.3.4. Company D

4.3.5. Company E

4.3.6. Company F

4.3.7. Company G

4.3.8. Company H

4.3.9. Company I

5. Recommendations and Implications

5.1. Sustainability Should Be a Long-Term Strategy

5.2. Sustainability Should Be Transparent

5.3. Sustainability Efforts Should Be Properly Communicated Externally

5.4. Sustainability Should Be Considered as Contributing to the Longevity of the Business

5.5. The Social Aspect of Sustainability Is also Important

5.6. What to Do, If in the ‘Situational Quadrant’?

5.7. What to Do, If in the ‘Incremental Quadrant’?

6. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V. Sustainability as corporate culture of a brand for superior performance. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two decades of sustainability management tools for SMEs: How far have we come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J. Sustainability and business outcomes in the context of SMEs: Comparing family firms vs. nonfamily firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Enhancing the Contributions of SMEs in a Global and Digitized Economy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/industry/C-MIN-2017-8-EN.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Tillväxtverket. Basfakta om Företag. Available online: https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/foretagande/basfakta-om-foretag.html (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Khattak, M.S. Does access to domestic finance and international finance contribute to sustainable development goals? Implications for policymakers. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Long-Term Vision for a Sustainable Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/efe/news/long-term-vision-sustainable-future-2016-1220_en (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J.; Modig, F.; Hed Vall, G. Commitment to sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises: The influence of strategic orientations and management values. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, S.; Arya, B.; Ismail, K.M. Organizational sustainability determinants in different cultural settings: A conceptual framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. SMEs and CSR: An Approach to CSR in their Own Words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19; Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2020/2020_sustainable_development_report.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.; Boswell, K.; Davis, D. Sustainability and triple bottom line reporting-What is it all about? Int. J. Bus. Humanit. Technol. 2011, 1, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Government Offices of Sweden. Sustainable Business- a Platform for Swedish Action. Available online: https://www.government.se/49b750/contentassets/539615aa3b334f3cbedb80a2b56a22cb/sustainable-business---a-platform-for-swedish-action (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Bossle, M.B.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Vieira, L.M.; Sauvée, L. The drivers for adoption of ecoinnovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Gupta, K.; Rani, L.; Rawat, D. Drivers of sustainability practices and SMEs: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Scandinavia: An overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sweden and the 2030 Agenda-Report to the UN High Level Political Forum 2017 on Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/16033Sweden.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Revell, A.; Stokes, D.; Chen, H. Small businesses and the environment: Turning over a new leaf? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Klassen, R.D. Drivers and enablers that foster environmental management capabilities in small-and medium-sized suppliers in supply chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Drivers for the participation of small and medium-sized suppliers in green supply chain initiatives. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2008, 13, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Martínez, F.J.; Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á. Factors promoting environmental responsibility in European SMEs: The effect on performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Cosma, S.; Leopizzi, R. Stakeholder engagement: An evaluation of European banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bi, J.; Liu, B. Drivers and barriers to engage enterprises in environmental management initiatives in Suzhou Industrial Park, China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2009, 3, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E. Why SMEs invest in environmental measures: Sustainability evidence from small and medium-sized printing firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambra-Fierro, J.; Ruiz-Benítez, R. Sustainable business practices in Spain: A two-case study. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Berent-Braun, M.M.; Jeurissen, R.J.M.; de Wit, G. Beyond size: Predicting engagement in environmental management practices of Dutch SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, M.; Perry, M. Walking the talk? Environmental responsibility from the perspective of small-business owners. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A.; Buelens, M. Small-business owner-managers’ perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 425–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agan, Y.; Acar, M.F.; Borodin, A. Drivers of environmental processes and their impact on performance: A study of Turkish SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Why and how to adopt green management into business organizations? The case study of Korean SMEs in manufacturing industry. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Rodríguez, J.F.; Ulhøi, J.P.; Madsen, H. Corporate environmental sustainability in Danish SMEs: A longitudinal study of motivators, initiatives, and strategic effects. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Guerra, D.; van der Zwan, P. What drives environmental practices of SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Sustainability management and small and medium-sized enterprises: Managers’ awareness and implementation of innovative tools. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods and Business: A Skilled-Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-26684-6. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. An Expanded Sourcebook: Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780803946538. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.R. Skype: An appropriate method of data collection for qualitative interviews? Hilltop Rev. 2012, 6, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. User Guide to the SME Definition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/conferences/stateaid/sme/smedefinitionguide_en.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 257–270. ISBN 9780761948872. [Google Scholar]

- Longoni, A.; Golini, R.; Cagliano, R. The role of new forms of work organization in developing sustainability strategies in operations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2017, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nordlund, A.; Westin, K. Examining drivers of sustainable consumption: The influence of norms and opinion leadership on electric vehicle adoption in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Social Sustainability. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/our-work/social (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Rao, P. Greening the supply chain: A new initiative in South East Asia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, I.; Guillén, M.F.; Macpherson, J.M. Global competition, institutions, and the diffusion of organizational practices: The international spread of ISO 9000 quality certificates. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why Companies Go Green: A Model of Ecological Responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Date of the Interview | Interviewee | Number of Employees and Type | Duration of SD | Customer Segments | Markets | Suppliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 24 March 2020 | The CEO/Sales Director | 28 Type 2 | More than 2 years | Public and B2B | Domestic and international in the EU | Within the EU |

| B (1–3) * | 30 March 2020 | The Sustainability Coordinator | 79 Type 2 | Extended period | Public and B2B | Primarily domestic and the Nordic region | None |

| B1 | 47 | ||||||

| B2 | 11 | ||||||

| B3 | 18 | ||||||

| C | 2 April 2020 | The CEO, and the Sustainability Coordinator | 35 Type 1 | Roughly 7 years | B2B and B2C (only a few items) | Nordic region and the EU | Outside the EU |

| D | 3 April 2020 | The Environmental and Sustainability Coordinator | 93 Type 2 | Roughly 1.5 years | Public and B2B | Primarily the Nordic region and some in Europe | Primarily Sweden and some outside the EU |

| E | 15 April 2020 | The Quality Manager | 107 Type 1 | Roughly 7 years | B2B and B2C | Domestic and international EU and non-EU | Outside the EU |

| F | 15 April 2020 | The CEO | 100 Type 1 | Extended period | Public and B2B | Domestic and international EU and non-EU | Within and outside the EU |

| G | 6 May 2020 | The Sustainability Coordinator | 120 Type 1 | Extended period | B2B | Primarily international within the EU and non-EU | Within the EU |

| H | 8 May 2020 | The Sustainability Manager | 180 Type 2 | Extended period | Public, B2B, and B2C | Primarily domestic | Within and outside the EU |

| I | 11 May 2020 | The CEO | 32 Type 1 | Roughly 8 years | Public and B2B | Primarily EU and some non-EU | Within the EU |

| Type of Sustainability Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Internal social sustainability | Company C | “it’s our employees, colleagues, and the working conditions, where we are following the law. As a high-quality company, we take care of our employees, but we are a small company of 35 people and are more or less like a family, so we are very good at internal social issues” |

| Company B | “we work a lot with things like reducing stress and things like that internally…our main resource is our employees, so we are trying to make sure that they do not overwork and so on—that is a priority for us” | |

| External social sustainability—local level | Company F | “We are also helping a lot of local athletic clubs, for example, and have a strategy around that. And I think that is also very important—I mean we do not sponsor very big football clubs, but we sponsor smaller ones and that’s our idea of contributing” |

| External social sustainability—global level | Company C | “then it comes to the suppliers and social issues—they also have to sign a code of conduct, if you are in Europe you only need to sign it … at the beginning of the working relationship. However, if you are located outside Europe, you need to sign it every year to secure that you are not using child labor, not giving unfair wages or bad working conditions” |

| Company E | “In China, most of the workers in the sewing companies … live at the factory but the children still live back home with their grandparents, so the families … meet once a year, and that’s during the Chinese New Year. That’s terrible. So, what we did was when…the children were out of school, they could go to the factory, and we have a school for them there. And then they could meet the parents in the evenings and have a nice time” | |

| Company I | “All our fabrics and suppliers, all our production plants are in Europe, and we still have a demand when it comes to sustainability…, as they are very definite and well-connected. So all our suppliers and product producers’ needs to meet the requirements” | |

| Internal environmental sustainability | Company D | “The management has developed a strategy, “zero vision”—we want zero emissions to air, zero impact on the working environment and zero pollution of water and soil- which is what we work for” |

| Company G | “the production is run by green energy, so we are saying that the production is climate-neutral, so there aren’t any emissions from the energy production” | |

| External environmental sustainability | Company I | “We work with their local legal parts to fulfill sustainability and environmental issues. Also, when it comes to the fabric suppliers, we are pushing them to manufacture and develop new fabrics, which are more environmentally friendly than the ones on the markets right now” |

| Company H | “biodiversity is also an important part because urbanization puts a lot of pressure on biodiversity. So, we try to work very broadly on both the positive and the negative side” | |

| Company E | “Its different sustainability, it’s very difficult because in the US, or China you have to have a plastic bag around everything” | |

| Government | Company A | “Our operations are conducted in a way that the environment is preserved but that’s not our main focus. Our main focus is on the REACH legislation, which covers what kind of substances you’re allowed to have in the products” |

| Company D | “the company has been working with environmental legislation. In the past, we wanted to fulfill what the law said but maybe not more than so” |

| Networks | Company I | “We are also collaborating with a few of the other brands in this area [sustainability] because we feel that we do so without having too much competition” |

| Company C | “We are a small company and we don’t have a sustainability department, so it’s just a small piece of a lot of different things that we do here, so for us, it’s important to be a part of a network, as the network can raise a lot of question and inspire with suggestions for how things can be done” | |

| Company F | “We try to be active in that part, as I think that it is important that our staff also get new ideas, so we can keep up and continue to develop our practice. So I think mostly that is why we are a part of this network.” |

| Competitors | Company B, division B1 | “it is our brand since we work with sustainable transport. We can see that other consultancies have also started working with sustainability, but we have worked with it for so long now that it’s easier to attract other interesting customers who have decided to do something and not only talk about sustainability” |

| Company B, division B2, and B3 | “We want to include more sustainability into their practice, but the kind of projects they have, don’t always integrate sustainability, so it is not really up to them to lift these issues in the projects” | |

| Company G | “our competitors or other producers are very well equipped for a sustainable future. And we as a small company need to work both harder and faster to be at the same level” | |

| Company E | “Maybe we don’t earn so much money in China right now, but in 10 years maybe it’s our biggest market. Then we still have our competitors, but we have a good brand—so we have to trust our brand” |

| Suppliers | Company A | “you would have to go through some kind of supplier evaluation process especially when working abroad”, but then again “Supplier will not ask if you are planning to take e.g., ISO 14001 in the next year or two, I mean they should be asking but they don’t” |

| Company C | “For the suppliers in the Far East, we’ve had a long relationship with them, and they have been our suppliers for many years—we are not looking for the best price, we also want to know the suppliers” | |

| Company D | “To our suppliers that we buy our products from, our raw materials and packaging and everything else, we also require them to meet our ‘code of conduct’. For us to be able to offer safe chemicals, we cannot buy raw materials…that are not manufactured correctly, or where the employees…do not have access to protective equipment for example. We need good suppliers who can give us good products” | |

| Company E | “There’s a lot of difference in Europe, and especially Sweden is a little bit ahead. That’s a little bit difficult because I want to get rid of all plastic bags, but then we can’t sell them in Japan, so it’s different for different markets” |

| Customers | Company D | “customers have a big impact…they are becoming more and more aware of the environment and that they should buy as environmental and sustainable products as possible…our customers ask if we can offer something that is more environmentally friendly or that may be eco-labeled or similar” |

| Company A | “Very few of our customers, maybe none of them are concerned over CSR [sustainability] or environmental issues, so we don’t work in an environment where we are pushed to be better at it from e.g., competition” | |

| Company B, division B2, and B3 | “We want to include more sustainability in our practice, but the kind of projects we get don’t always integrate sustainability, so it is not really up to us to lift these issues in the projects” | |

| Company C | “back in 2013 it also became a demand from our biggest customers and all of the big retailers in the market who resell our products. One day they started asking questions if we have this and that system and then we realized that it was something we needed to do” | |

| Company G | “at the moment we are reconsidering the whole social issues because we realize that we need to show this to our customers, as they are interested to see how the company is working with social issues” | |

| Company F | “It has been on very few occasions, that we have been followed up on these, which we think is a bad thing, as we are delivering a very good product according to these issues, so actually we would like them to follow up on things—but maybe they will in the future” | |

| Company H | “when it comes to public procurement, there is a big challenge when it comes to sustainability because the whole public procurement is focusing on price. So the lowest bidder wins the task, which means that it’s really hard to push issues like innovation, quality, and sustainability because you risk disqualifying yourself due to the cost” | |

| Company I | “If you think about it in that way, then you have to only focus on winning the tender for tomorrow. But the requirements will be more and more demanding. So, if you don’t have a focus on sustainability questions then there is no way of winning tenders at the end of the day anyway” |

| Community Surrounding | Company C | “Externally in society, our work is very active. We are located in a small city…, and our company is very active in our home city—so we invite schools and different associations to come and visit us and we try to be active in our community” |

| Company F | “our business is located in a small village, where there are not that many people…we are also helping a lot of local athletic clubs” | |

| Company A | “I think that it’s a legal demand from society as such, you need to have it and pay attention to how you use raw materials, how you source your waste and so on” | |

| Company I | “Now it’s so important saying you cannot be in this business without having it…seven years ago we wouldn’t even consider having one full-time employee working with that … So, it’s a high focus area and probably still will be for some years to come” |

| Employees | Company A | “… it’s also from an employees’ point of view—we want to be an attractive company as we are still recruiting people…And we need to have a policy [sustainability related] that is attractive in the eyes of employees, as you should be proud of the company you work in” |

| Company C | “Since we are telling our employees that they are working in a high-quality company, our company needs to work and behave accordingly” | |

| Company G | “Everybody has this chance to influence it…but it comes with so many different perspectives. So, I think for a company it’s very important to put down what sustainability means for our company” | |

| Company D | “Employees shouldn’t be afraid to bring up things that they don’t think are working so that we can do better” | |

| Company B | “We can see that it’s important for our employees because many people have chosen to work with us because they have passion for sustainability, and it gives them satisfaction to work with those sort of projects” | |

| Company I | “We have been quite attractive as an employer due to our focus on sustainability. So, we have people contacting us and sending in CVs and things like that, even if we don’t have open positions” |

| Organizational culture | Company D | “When it comes to the internal, I would say that we have an extremely big advantage in this company, the management and the owners think this is very important” |

| Company H | “it’s very important if we want to create social sustainability and value for the society, we have to put the 48 employees in the center of the development…it’s the next generation that we also have to focus on … it’s not about the market, it’s not about legislation—it’s the people that we have” | |

| Company F | “The first and most important factor is that I am building a company that must work sustainably … So, from the very beginning, it was much more internal factors, since I wanted to build a good foundation for the company” | |

| Company C | “We consider ourselves as a high-quality company and not only with the products we make but also in general … high-quality products and a high-quality company should be linked to social responsibility” | |

| Company I | “it’s never an option to compromise on sustainability for us … it’s not an option to not have it so high on the agenda, since we know our industry has a negative impact” | |

| Company E | “My target now for the last year has been to get the owners to prioritize sustainability … Last summer I was visiting them all, the owner and the children, and had some sustainability talks with them. It was so good, and I think we will get the resources and it will be on top of the management that sustainability is important ” |

| Brand image and reputation | Company G | “And even more brand image and improved reputation. I think that’s the main force that we see driving our sustainability work” |

| Company D | “it’s easier for us to market ourselves as a desirable company when we have this environment and sustainability work” | |

| Company A | “In our case, it is less about looking good and more about the economy” | |

| Company F | “We don’t communicate it [sustainability] that much as we address it, but it is not one of the most important aspects for us” | |

| Company E | “It’s difficult, we present our company as sustainable in what we do and everything, but at the same time we don’t want it to be the main focus” |

| Competitive advantage and strategic intent | Company A | “As we started working with different processes and we wanted to look more attractive in the international marketplace…we hired an external consultant who had a more modern approach to quality and environmental approach” |

| Company D | “becoming more competitive, we can stand out in the industry if we can offer more environmentally and sustainable products” | |

| Company C | “most of the products are made in Sweden and that is our heritage, and that is also our strategy” | |

| Company E | “I think this is ‘självklart’ [obvious], we need to have it—both internal and also for the future I think as the base for a company. It’s not like you shall beat your competitors on this—this is something you need to have to exist in the future. I think we have learned that” | |

| Company I | “Well, of course, a tiny bit of it, is for competitive reasons, because we know that the market has high demands on the garments that they want to wear…Hopefully, we can take some market shares from our competitors, who don’t have it so much on the agenda, and that makes us sleep well at night” |

| Size of the firm | Company C | “We are a small company and we don’t have a sustainability department, so it’s just a small piece of a lot of different things that we do here … I think it’s easy for the bigger companies with a whole department working with these questions, but for us, it’s not like that at all” |

| Company E | “We have suppliers in Turkey, Vietnam, and China … We have close cooperation, and we can trust them that they pay the salaries, that they have fire safety, safety in the production, and everything. So, that’s one of the most important factors for us. It’s a long relationship … but we make third-party audits from professional companies … they check the production and everything, and then we get a full report about everything … and they always find something, e.g., they work too much, … that they don’t use the protections in the production and so on. But it’s good, we have good control, and they know that we are coming every year, so they don’t dare to do anything” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsvetkova, D.; Bengtsson, E.; Durst, S. Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410242

Tsvetkova D, Bengtsson E, Durst S. Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410242

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsvetkova, Desislava, Emma Bengtsson, and Susanne Durst. 2020. "Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410242

APA StyleTsvetkova, D., Bengtsson, E., & Durst, S. (2020). Maintaining Sustainable Practices in SMEs: Insights from Sweden. Sustainability, 12(24), 10242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410242