Building a Care Management and Guidance Security System for Assisting Patients with Cognitive Impairment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spatial Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

1.2. Spatial Cognitive Impairment Device for Dementia Patients

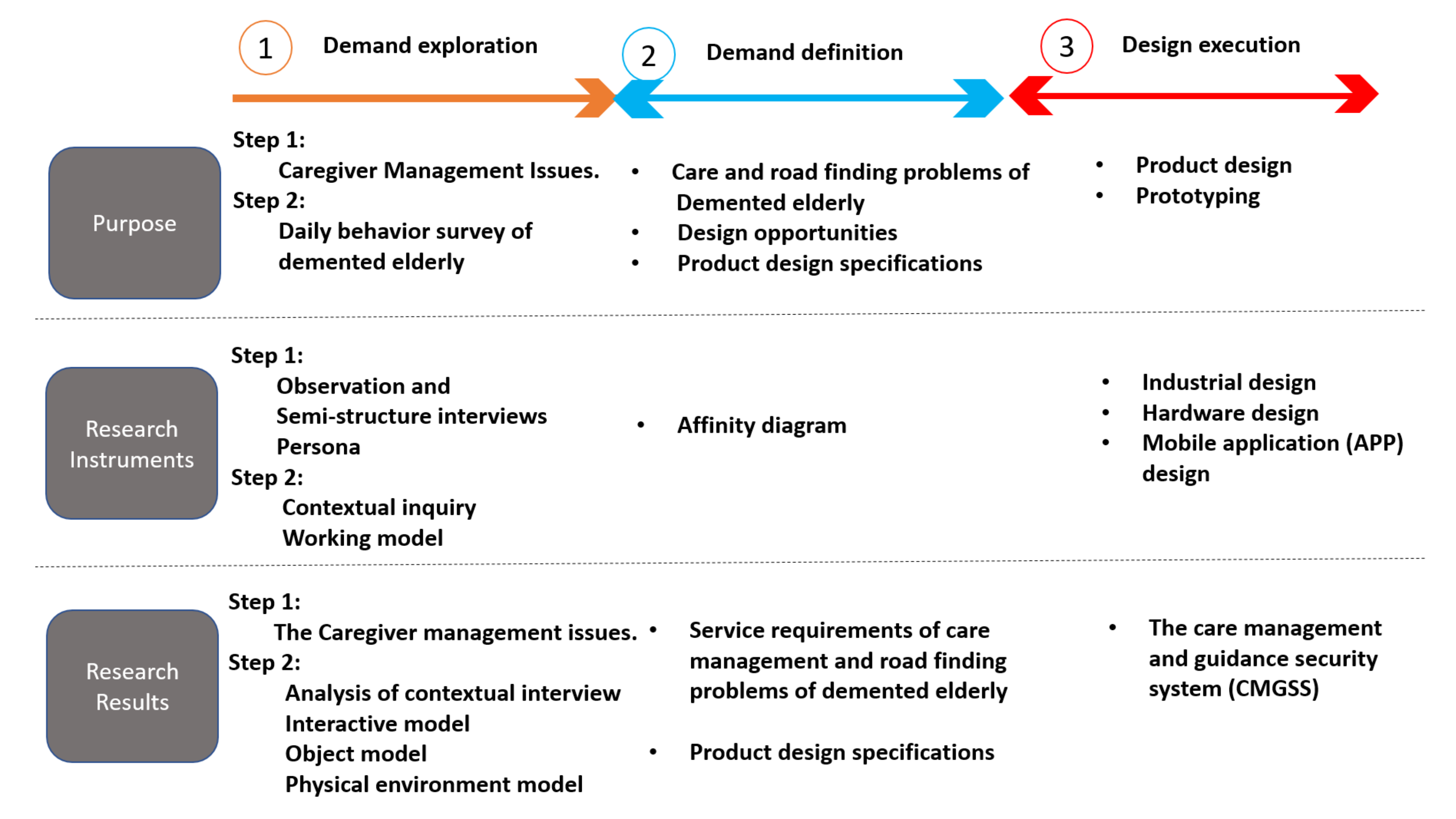

2. Methods

2.1. Demand Exploration Stage

2.1.1. Semi-Structured Interview

2.1.2. Contextual Inquiry

2.1.3. Working Model

2.2. Demand Definition Stage

2.3. Design Execution Stage

2.4. Reliability and Validity Measures

- (1)

- Participatory observation (i.e., field survey) and recording: in the process of contextual inquiry, participatory observation was used to collect data [25,26], the interview content was documented word by word after recording, and the participant feedback method was used to invite the participants to discuss and comment on the interview draft and research conclusion, so as to establish the credibility of the interview content.

- (2)

- The observation data were analyzed by the triangulation method, which combined the AEIOU (activity, environment, interaction, object, and user) analysis method with the interactive model, environment model, and object model to eliminate any contradictory behaviors in the data. In addition, the validity and reliability of this study were examined by prolonging the interview and participation time in the research site and recording the authenticity of the actual observation interview content [27].

- (3)

- External audit mechanism: in order to ensure the validity and confidentiality of the archives, we signed the consent form with the caregiver’s family and the participants before the experiment. In the consent form, we mentioned the time limit of the file’s existence and the location and time effect of the recording and photo files, so as to protect from data leakage of the subjects’ information.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Care management survey: The data collected from the semi-structured interviews of four caregivers were analyzed from human resource allocation, dependence on caregivers, immediate mastery of dementia behavior, spatial cognitive impairment, and daily activity area.

- Persona: In this study, we used the method of persona analysis [23] to select a total of three persons (2 mild and 1 moderately cognitively impaired patient) whose upper limbs could be used freely (the Barthel index was mild, provided by the care center). They were represented by cases 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

- Analysis of contextual inquiry: In this study, the three selected cases were observed. Through observation and interview of the context survey experiment, the interaction behavior and information about the daily activities in the care center were collected from activities, the environment, interactions, objects, and users.

- Behavior modeling analysis: Through the construction of the behavior model [28], the existing daily life behavior information collected from the above cases formed three working models, namely, the interactive, object, and environment models, as follows;

- (1)

- Interaction model: The interaction model can present a way of contact and interaction between the case, the environment, and others, and it can be simplified into a simple and easy to understand behavior model. In this study, the interaction model between the three cases and other people and the field in the daily activities of the care center was drawn, and the obstacles in the interaction process were displayed.

- (2)

- Object model: Through the object model, we can see whether there are any obstacles to the tools and implements used in daily life.

- (3)

- Environment model: It is a field of daily activities in the care center. It can describe the spatial functional layout and structure of daily behavior. According to the purpose and method of use, as well as the activity route of the case in the environment, various related objects are presented. For example, Figure 2 [29] showed the behavior of the patient engaging in gardening activities indoors and outdoors. It included indoor and outdoor planting activities, wheelchairs pushed by patients and caregivers, configuration of various gardening tools, and behavior of the patients observed during the activity.

3. Results

3.1. Demand Exploration Stage

3.1.1. Care Management Survey

3.1.2. Persona

3.1.3. Contextual Inquiry

3.1.4. Working Model

- (1)

- Interactive model: This model integrated and depicted the interaction mode of people and things encountered by the elderly with dementia in their daily life, as shown in Figure 4. In this study, the cognitively impaired subjects sought the help of caregivers because they could not find their destination (such as the living room). In view of the occurrence of wandering events, caregivers made irregular inspections to confirm the position of each elder. However, such decision making could not monitor the movement of the cognitively impaired elderly in a timely manner and prevented the elderly from leaving the care environment uncontrolled.

- (2)

- Object model: This model was based on the objects used by the elderly in the process of route recognition and movement, Table 2. According to the different modes of autonomous action, the walking cognitively impaired elderly rely on crutches and armrests, while others use wheelchairs. It was found that due to the settings of the surrounding corridors in the environment, the actions of the elderly with cognitive impairment were slightly hindered, and they would seek help from caregivers or push them away directly, which caused problems for other elders around them. As a reference for exploring the environment on the route, the various indicators in the care environment were not obvious, and so the caregiver was required to remind or guide the patients from time to time. For example, a pattern on the door of a patient’s room, which meant that caregivers could help patients explore themselves by reminding them of the pattern on the door.

- (3)

- Environment model: This model reduced the proportions of the care environment and marked the moving process of objects, people, etc., around them. In this model, we can see the space where the wheelchair was stacked and the rest positions of other elders in the activity space, and how this leads to moving line problems. In the process of exploration, the elderly would leave the activity space, and there were risks of moving and leaving the care environment as shown in Figure 5. (Note that in the middle of the model, there are three caregivers, and the others are in the dormitory to assist in washing, etc.).

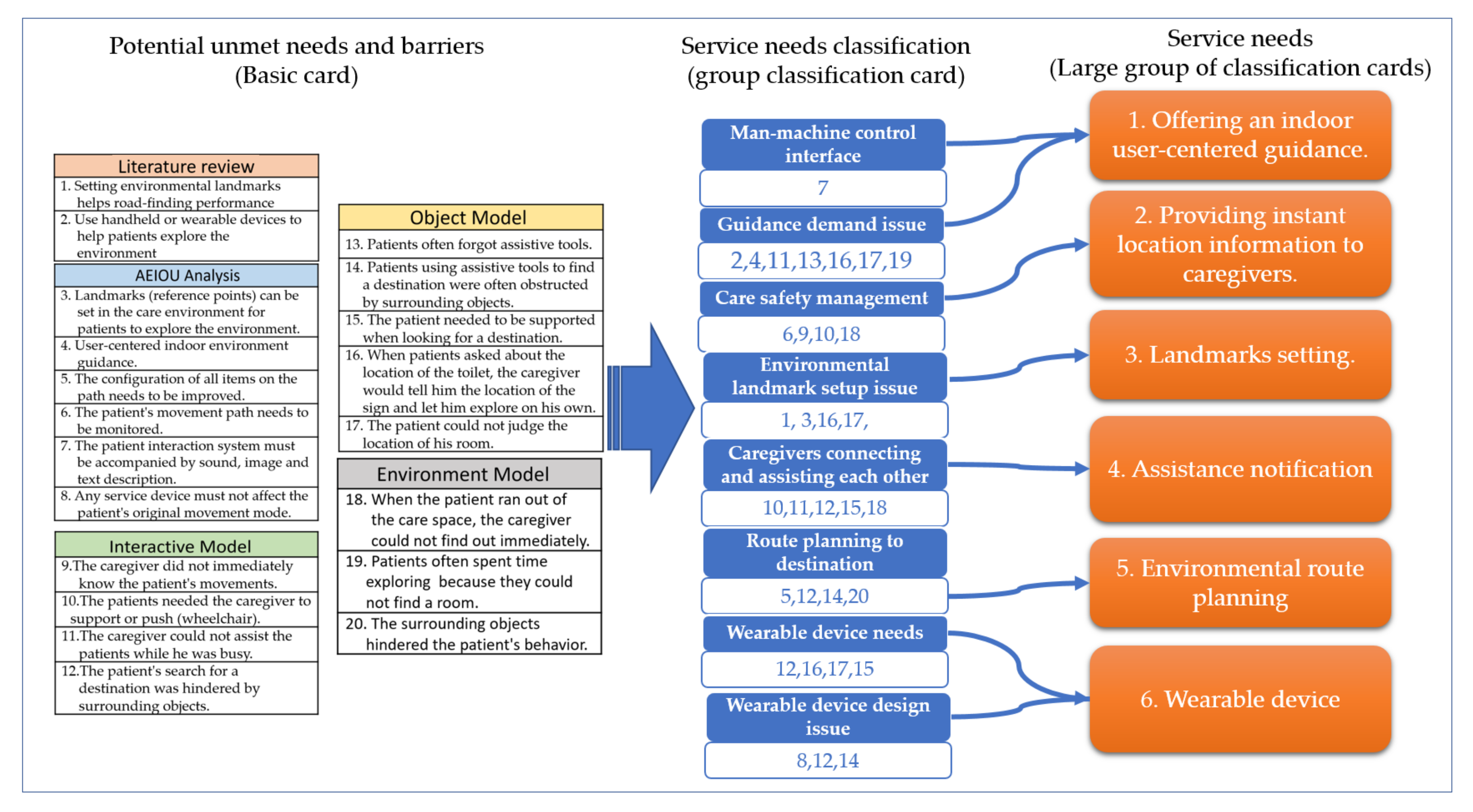

3.2. Demand Definition Stage

Caregiver Management Issues

- Offering an indoor user-centered guidance: A user-centered indoor guidance service, combining graphical presentation (such as tablet computers) or voice-cue direction guidance, helps elders with dementia quickly reach their goals and carry out their daily activities, such as toileting, drinking water, taking medicine, etc. It can reduce safety problems occurring during the pathfinding process of patients.

- Providing instant location information of elders with dementia to caregivers: The caregiver can grasp the position of the self-moving elderly. The device can also combine the indoor positioning function to let the caregiver immediately know the location of elders and determine whether assistance is needed to further prevent the elderly from entering dangerous areas.

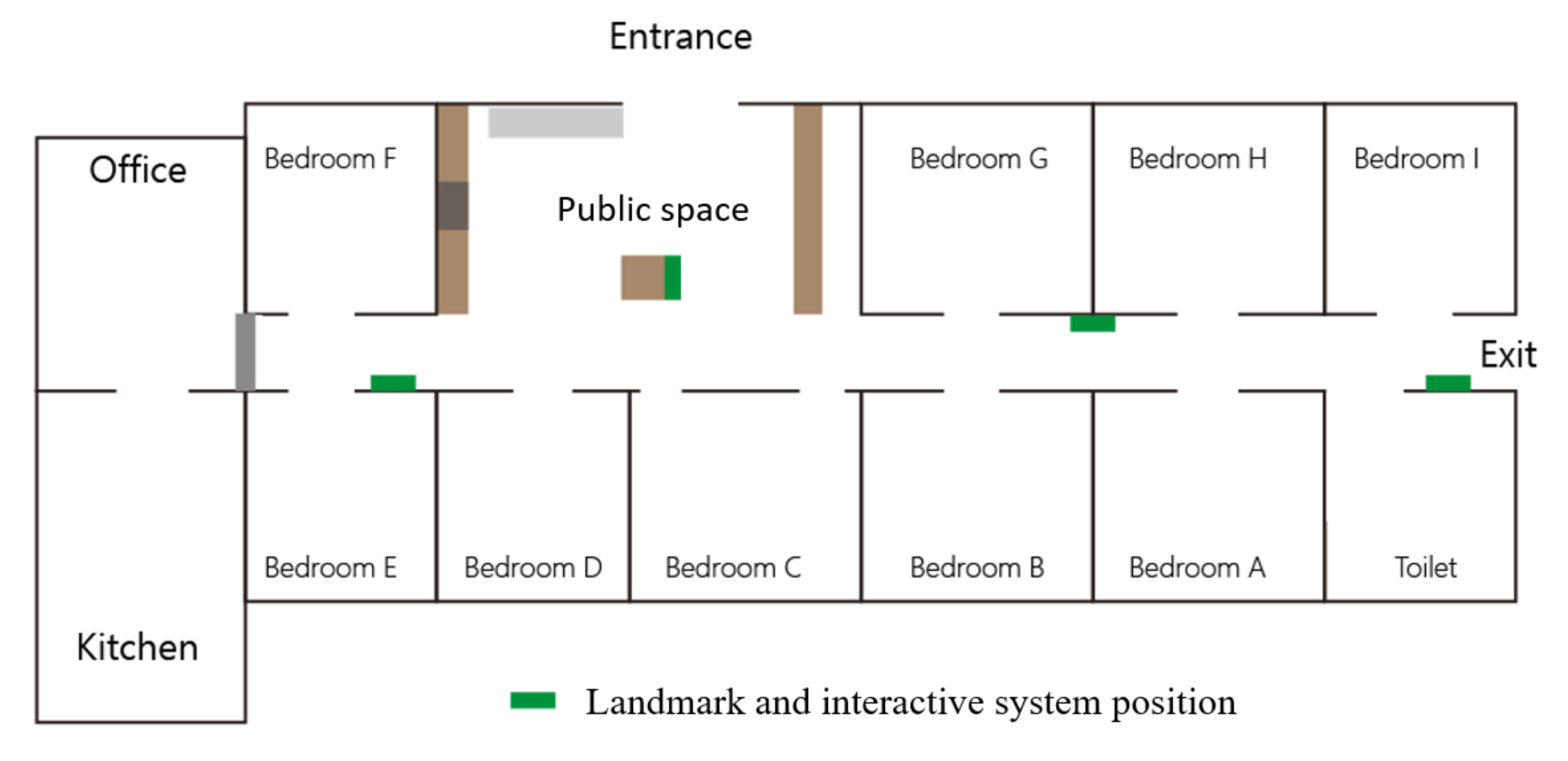

- Landmarks setting: Clear landmarks can reduce errors in pathfinding by placing landmarks in patient’s familiar places as a reference for finding their way. The design of the landmarks is presented in the form of text, voice prompts, and images that can improve the accuracy of pathfinding.

- Assistance notification: Elders will call their caregivers with gestures or language, but they sometimes missed the opportunity for service demand. If the cognitively declined elderly use a device to inform all caregivers, they can immediately complete the needed care requirements.

- Environmental route planning: For areas where patients often go, such as toilets, restaurants, pantry, etc., special areas for wheelchair placement should be provided to reduce the obstacles and dangers in the path.

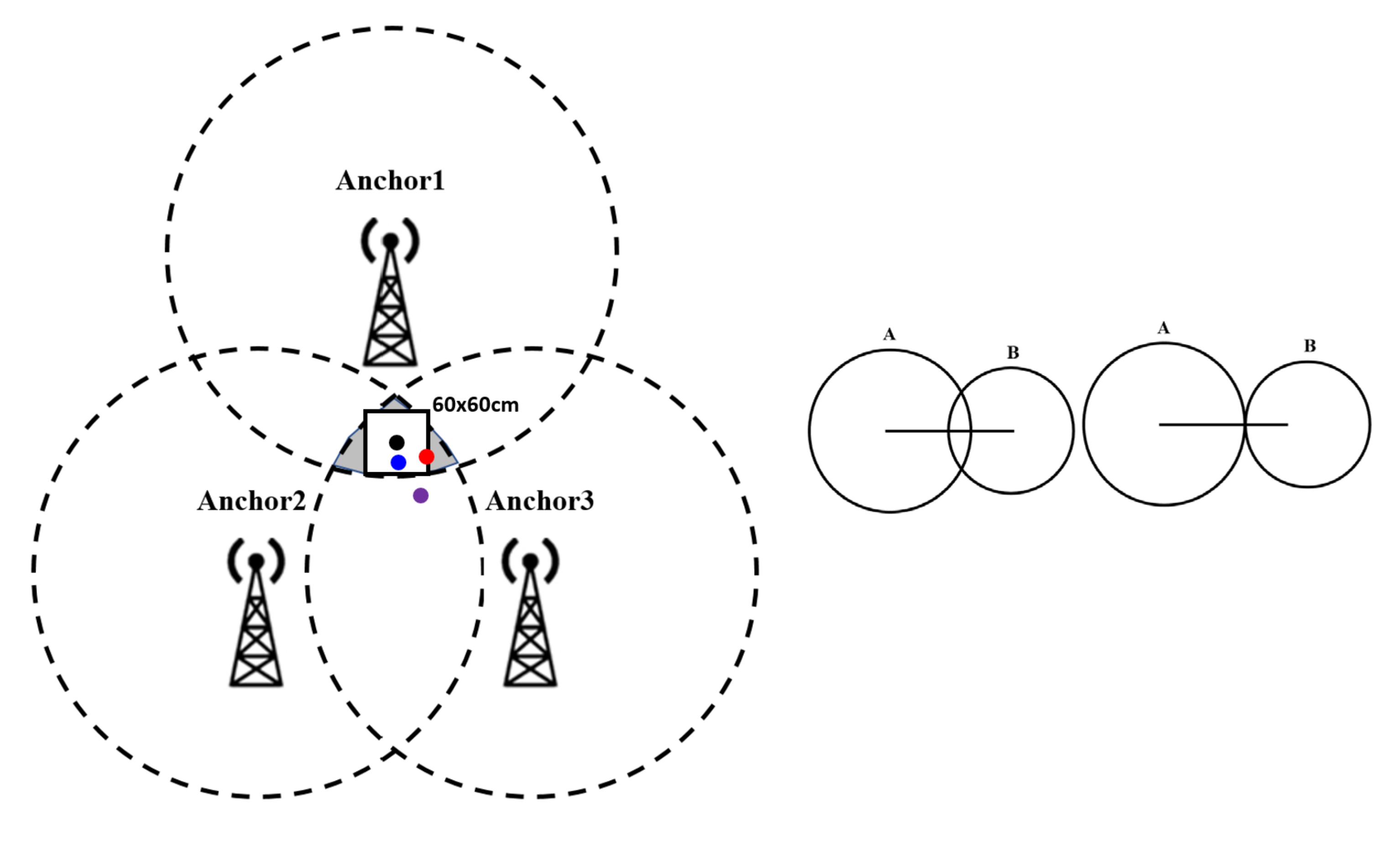

- Wearable device: A wearable device is used as a guide for indoor route guidance. It combines the Wi-Fi’s distance signal judgment and sensor module calculation to achieve a higher accuracy of indoor positioning. The device can also work with mobile applications which can calculate the direction and suitable path for optimal route guidance.

3.3. The Design of the Care Management and Guidance Security System (CMGSS)

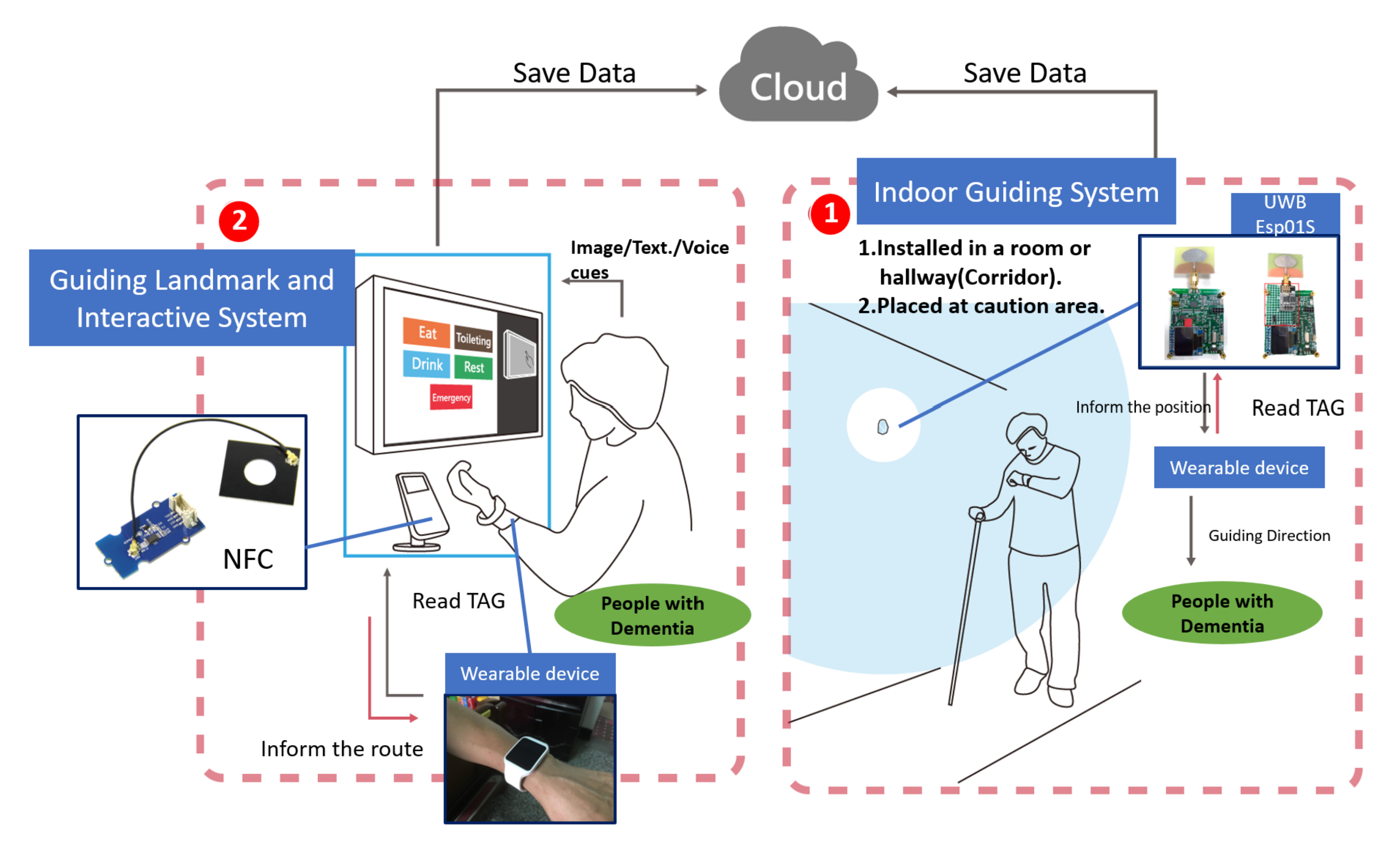

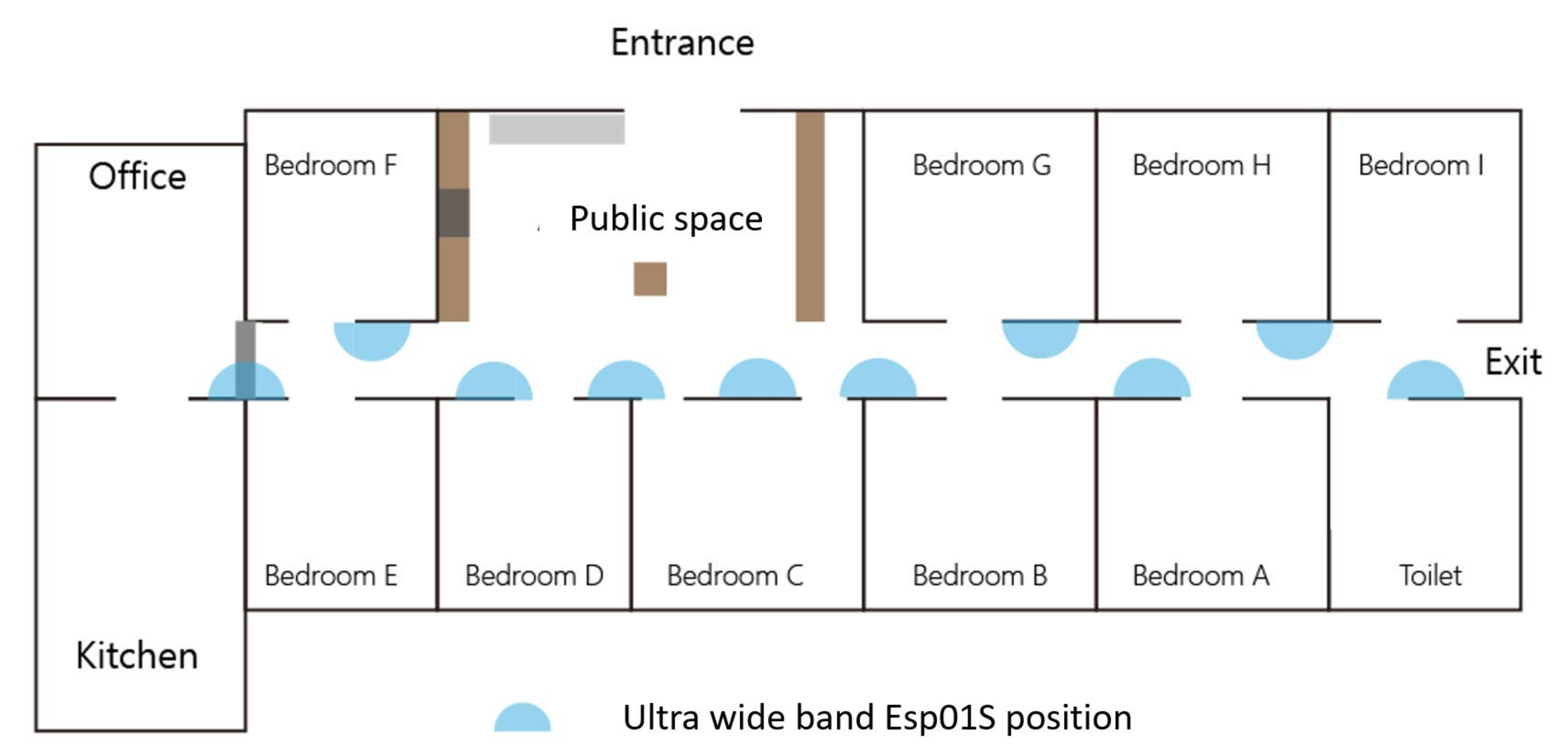

- Indoor guiding system (IGS): Guiding landmarks are set in the places where patients regularly go (restaurants, toilets, public spaces, etc.) and are linked to the guiding landmark interaction system through the near-field communication (NFC) of the smart watch (Figure 7). Patients can set the destination from the guiding landmarks through voice, image, or text message. Then, the message is sent back to the smart watch, where the near-field component uses the orientation sensor to define the destination and current location of the patients. The screen of the smart watch displays the guiding direction after the path is calculated with the current location. When the patient moves to the destination, the ultra-wide band (UWB) system Esp01S will locate the signal. After the Esp01s signal matches the destination (Figure 7), the device terminates the guidance.

- Guiding landmark interactive system (GLIS): The GLIS, whether set in the toilet, tearoom, restaurant, bedroom, etc., is composed of a touch screen and an NFC sensor (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). Through the screen interface, it displays daily activities, such as dining, drinking, toileting, resting, for patient selection. The patient connects to the NFC with the smart watch. The screen interface of the GLIS presents the graph with texts options and a voice asks about daily activities. After the patients’ select their desired activity by voice or touching the screen, the guiding landmark will transmit a message to the smart watch and guide the patients to their destination. When the patient moves to the destination, the smart watch senses the UWB signal. After the wireless signal matches the destination, the device terminates the guidance.

- Monitoring system: The system uses multiple ultra-wide band devices, installed in the environment, to detect the patient’s smart watch and to transmit the patient’s number and position (Figure 11). Through the preset coordinates and the calculation of the triangulation method, the location of the patient in the environment is transmitted back to the monitoring screen of the care manager (Figure 11). The caregiver is notified if the patient does not act in accordance with their chosen purpose, or if they begin wandering in the environment. The monitor screen displays the overall indoor map of the care environment and the number of people in each area (room, corridor, activity space, etc.). The daily activities of the patient are recorded and transmitted back to the family members through the mobile application.

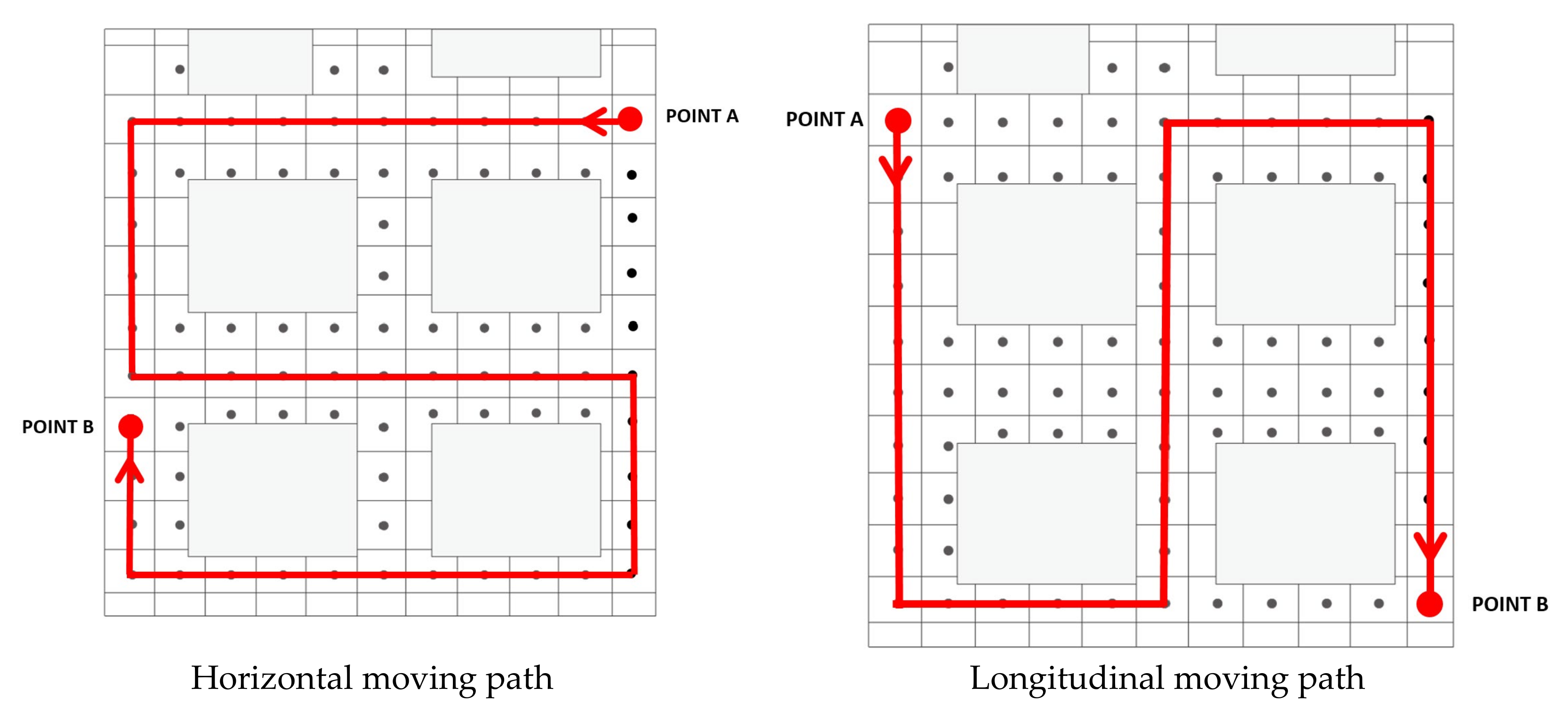

3.4. The Indoor Positioning Technology Verification Experiment

3.4.1. Stimulus

3.4.2. Experimental Process

3.4.3. Experiment Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Guidance on Route Finding

4.2. Care Monitoring and Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prince, M.; Anders, W.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.; Wu, Y.; Prina, M. Global Report on Dementia 2015; I.A.F. Dementia: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dementia Prevention and Care Policy Framework and Action Plan 2.0; Ministry of Health and Welfare, Ed.; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.; Tang, L. Guide to the Care of Dementia; Raw Water Culture Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McShane, R.; Gedling, K.; Keene, J.; Fairburn, C.; Jacoby, R.; Hope, T. Getting lost in dementia: A longitudinal study of a behavioral symptom. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1998, 10, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, M.C.; Jacobs, W.J. Topographical disorientation in community-residing patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.C.; Algase, D.; Whall, A.; Lian, J.; Liu, H.C.; Lin, K.N. Getting lost: Directed attention and executive functions in early Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2004, 2004, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, M.F.; Mendez, M.A.; Martin, R.; Smyth, K.A.; Whitehouse, P.J. Complex visual disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1990, 1990, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passini, R.; Rainville, C.; Marchand, N.; Joanette, Y. Wayfinding with dementia: Some research findings and a new look at design. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1998, 15, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, G. The Importance of Food and Mealtime in Dementia Care: The Table Is Set; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, E.K.; Volicer, L.; Hurly, A.C. Management of Challenging Behaviors in Dementia; Health Professions Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.S.; Chubb, C.; Huff, F.J. Visual identification and spatial location in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Cogn. 2003, 52, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, E. Wayfinding difficulties among elders with dementia in an assisted living residence. Dementia 2014, 13, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.M.; Chiu, Y.C.; Liang, J.; Chang, T.H. Risky wanderingbehaviors of persons with dementia predict family caregivers’ health outcomes. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.L.; Hile, H.; Kautz, H.; Borriello, G.; Brown, P.A.; Harniss, M. Indoor wayfinding: Developing a functional interface for individuals with cognitive impairments. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2006, 3, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, I.; Baldwin, C.L. Facilitating route memory with auditoryroute guidance systems. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminoyama, H.; Matsuo, T.; Hattori, F.; Susami, K.; Kuwahara, N.; Abe, S. Walk navigation system using photographs for people with dementia. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Human Interface and the Management of Information, Beijing, China, 22–27 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, G.; Schmieg, P. Dementia-Friendly Architecture: Environments that Facilitate Wayfinding in Nursing Homes. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2009, 24, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, L.E.M.; Zelek, J.; Lam, I.; Black, S.E.; Carnahan, H. Application of a Tactile Way-Finding Device to Facilitate Navigation in Persons with Dementia. Assist. Technol. 2011, 23, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Study on Outdoor Positioning with Wifi/GPS, in Department of Land Administration; National Chengchi University: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, S.-W.; Hsu, C.-W. A Smart, Caring, Interactive Chair Designed for Improving Emotional Support and Parent-Child Interactions to Promote Sustainable Relationships Between Elderly and Other Family Members. Sustainability 2019, 11, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, B. Service Design. Design Dictionary: Perspectives on Design Terminology; Erlhoff, M., Marshalle, T., Eds.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institute Information Industry. Service Experience Engineering Method—Blueprint. Tool. Case; Institute Information Industry: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.; Reimann, R.; Cronin, D.; Noessel, C. About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakita, J. The Original KJ Method; Kawakita Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ary, D.; Jacobs, C.; Sorensen, C. Introduction to Research in Education; BWadsworth, Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, L.R.; Mills, G.E.; Airasian, P. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications; Merrill/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, H.; Holtzblatt, K. Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, W.-W.; Ma, Y.-C.; Wong, W.-K.; Yeh, Y.-T.; Wang, W.-I.; Cheng, S.-H. An Indoor Gardening Planting Table Game Design to Improve the Cognitive Performance of the Elderly with Mild and Moderate Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, R.; Mizugaki, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Maeda, D.; Miyazaki, M. TOA/TDOA hybrid relative positioning system using UWB-IR. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Radio and Wireless Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–22 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barrash, J. A historical review of topographical disorientation and its neuroanatomical correlates. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998, 20, 807–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W. Spatial Navigation and Dementia; Taiwan Gerontology Forum: Tainan City, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. Life Experience of Family Caregivers Accompanying Dementia Patients in Outpatient Clinics; Department of Nursing, Zhongshan Medical University: Guangzhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Observation | Points of Demand | |

|---|---|---|

| Activities |

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

| Interactions |

| Whether to use a device to guide the cognitively impaired elders to the place they want to go. |

| Objects |

| How to improve movement routes in public areas? |

| Users |

| Inform the caregivers at any time by means of the device. |

| Category | Name | Object | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal belongings | A cane |  | Used in the process of assisting walking elders to move steadily, the canes have four claw crutches. The elders sometimes forget them and leave them in their seats. Their use is hindered due to the positioning of the wheelchair in the corridor. |

| Wheelchair |  | 1. The most common tool in the care environment, used even for the elderly with walking ability during rest time. 2. The movement process was divided into autonomous movement and the assistance of caregivers. 3. The wheelchair was large in size and placed in the corridor when not in use, causing obstruction to the moving line. | |

| Space settings | Indicator |  | Location-oriented reference: guiding the direction. The elderly with mobility would ask about the location of the toilet, and the caregiver would tell them the location of the sign for the elderly to explore by themselves. The placement of the instructions was combined with information on bulletin boards, which often caused confusion among patients. |

| Living room diagram |  | Location-oriented reference: guiding the location. The elderly with dementia who had the ability to act were unable to judge the location of their own room. The caregiver would make a distinction between the design of the room and tell the elder what the pattern on the door of his room was, so that the elderly could explore by themselves. | |

| Handrail |  | The handrail provided the elderly with support, which can help the elderly share their weight during movement. In addition, the range of handrails provides a direction for the elderly to walk. | |

| Problem arrangement | 1. Wheelchair placement in the care environment hindered the movement of other patients. 2. Landmarks and indicators in the environment were not obvious. 3. Patients used clues, such as images, as references for exploration. | ||

| Category | Black Dot | Blue Dot | Red Dot | Purple Dot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | 75 | 38 | 34 | 3 |

| First | Second | Third | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal moving path | 63 | 57 | 66 | 62 |

| Longitudinal moving path | 76 | 83 | 60 | 73 |

| Unit: cm. |

| Category | Original Distance (cm) | Error Range (cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall thickness of 18 cm | Open door test | 63~70 | 2.4~2.6 |

| Closed door test | 63~69 | 2.4~2.7 | |

| Wall thickness of 83 cm | 600~642 | −503~−504 | |

| 260~520 | −244.6~−249.6 | ||

| 254~269 | −122~−122.6 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tseng, W.S.-W.; Wong, W.-K.; Shih, C.-C.; Su, Y.-S. Building a Care Management and Guidance Security System for Assisting Patients with Cognitive Impairment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410516

Tseng WS-W, Wong W-K, Shih C-C, Su Y-S. Building a Care Management and Guidance Security System for Assisting Patients with Cognitive Impairment. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410516

Chicago/Turabian StyleTseng, Winger Sei-Wo, Wing-Kwong Wong, Chun-Chi Shih, and Yong-Siang Su. 2020. "Building a Care Management and Guidance Security System for Assisting Patients with Cognitive Impairment" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410516

APA StyleTseng, W. S.-W., Wong, W.-K., Shih, C.-C., & Su, Y.-S. (2020). Building a Care Management and Guidance Security System for Assisting Patients with Cognitive Impairment. Sustainability, 12(24), 10516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410516