Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

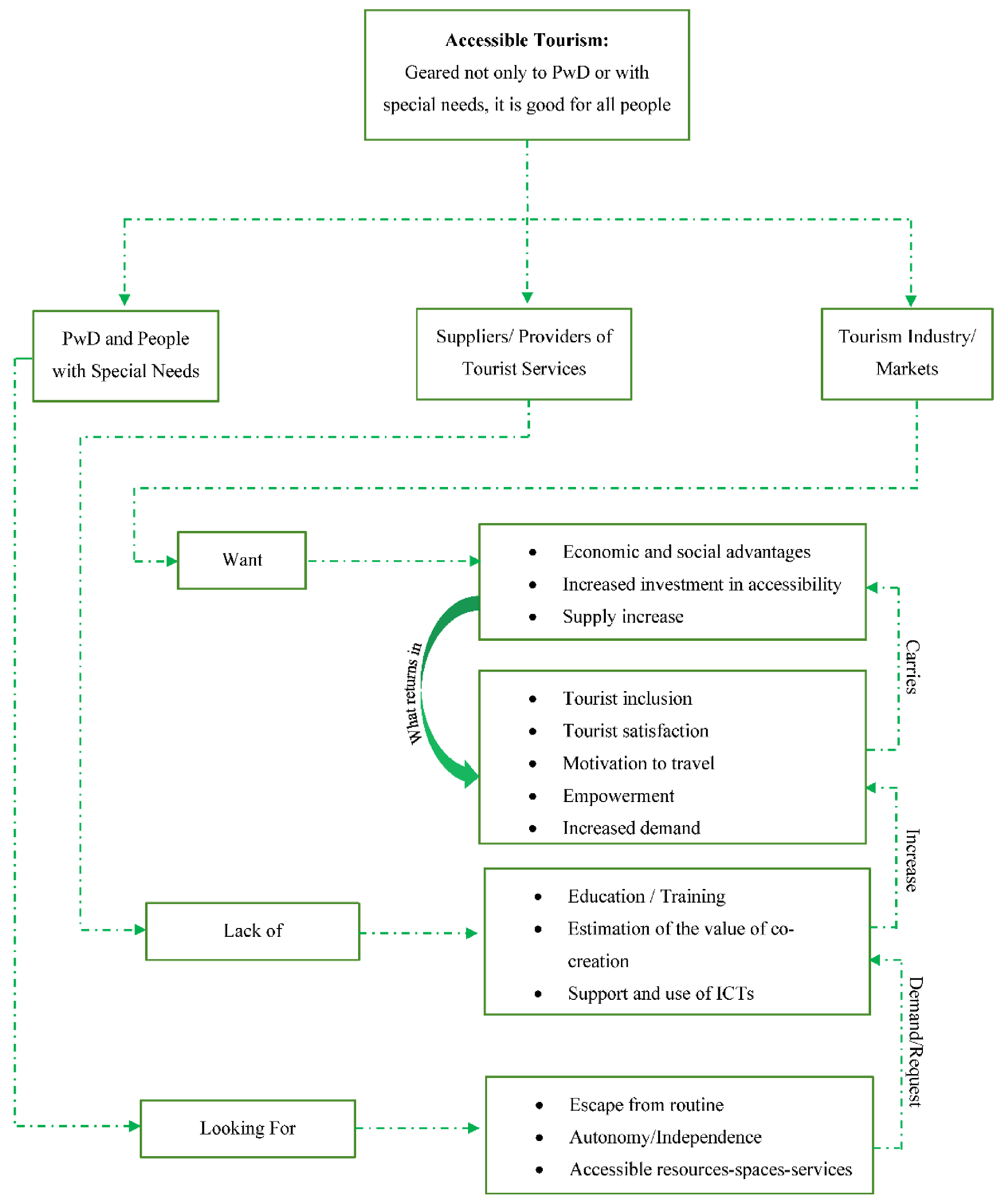

2.1. Getting to Know the Disabled Traveler

2.2. Accessibility for Tourism Inclusion

2.3. Accessible Tourism as an Emerging Market Bet

3. Materials and Methods

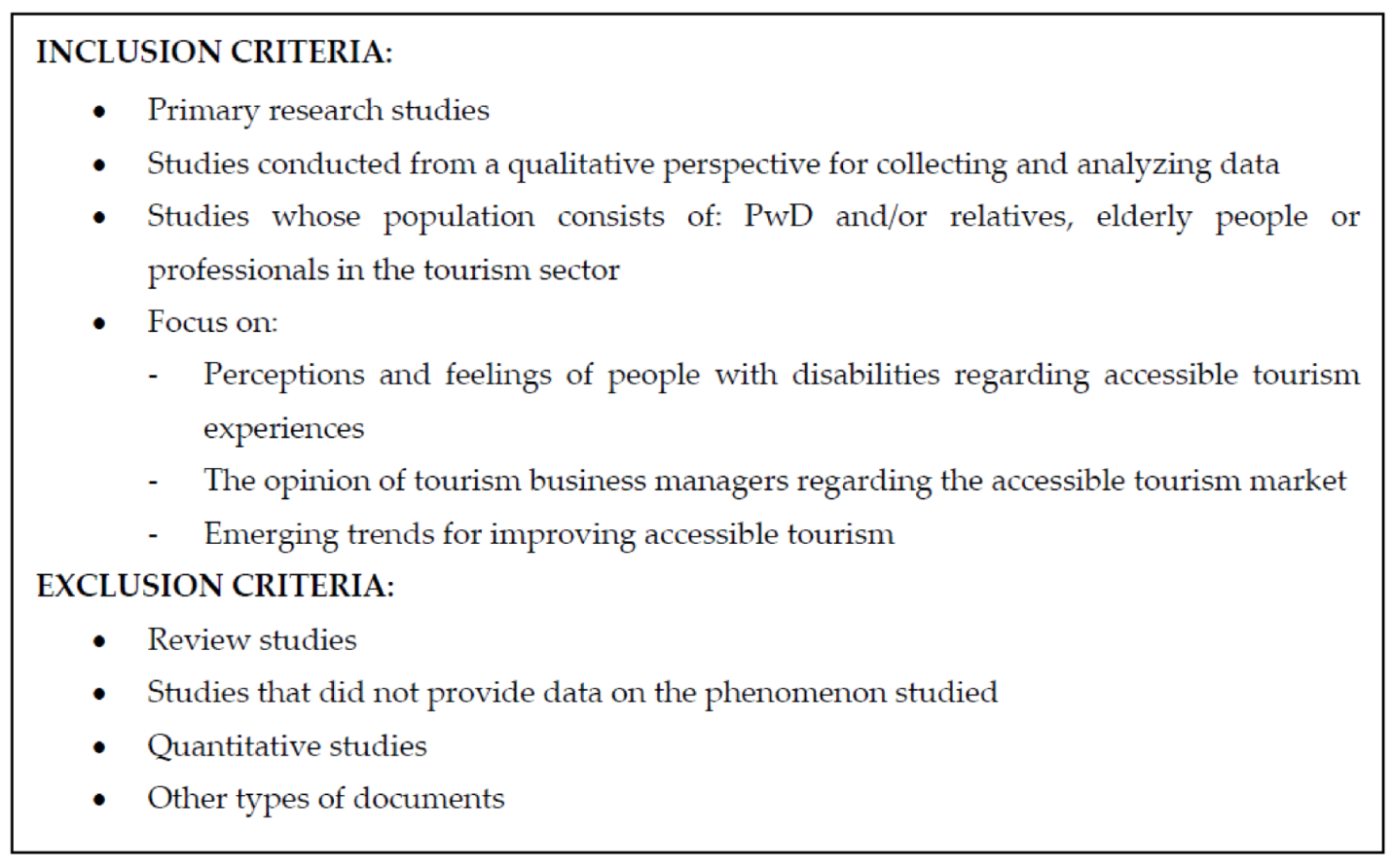

3.1. Review of the Design Protocol

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Selection of Studies

3.4. Data Extraction

3.5. Analysis of the Content

3.6. Analysis of the Methodological Quality of the Studies

4. Results

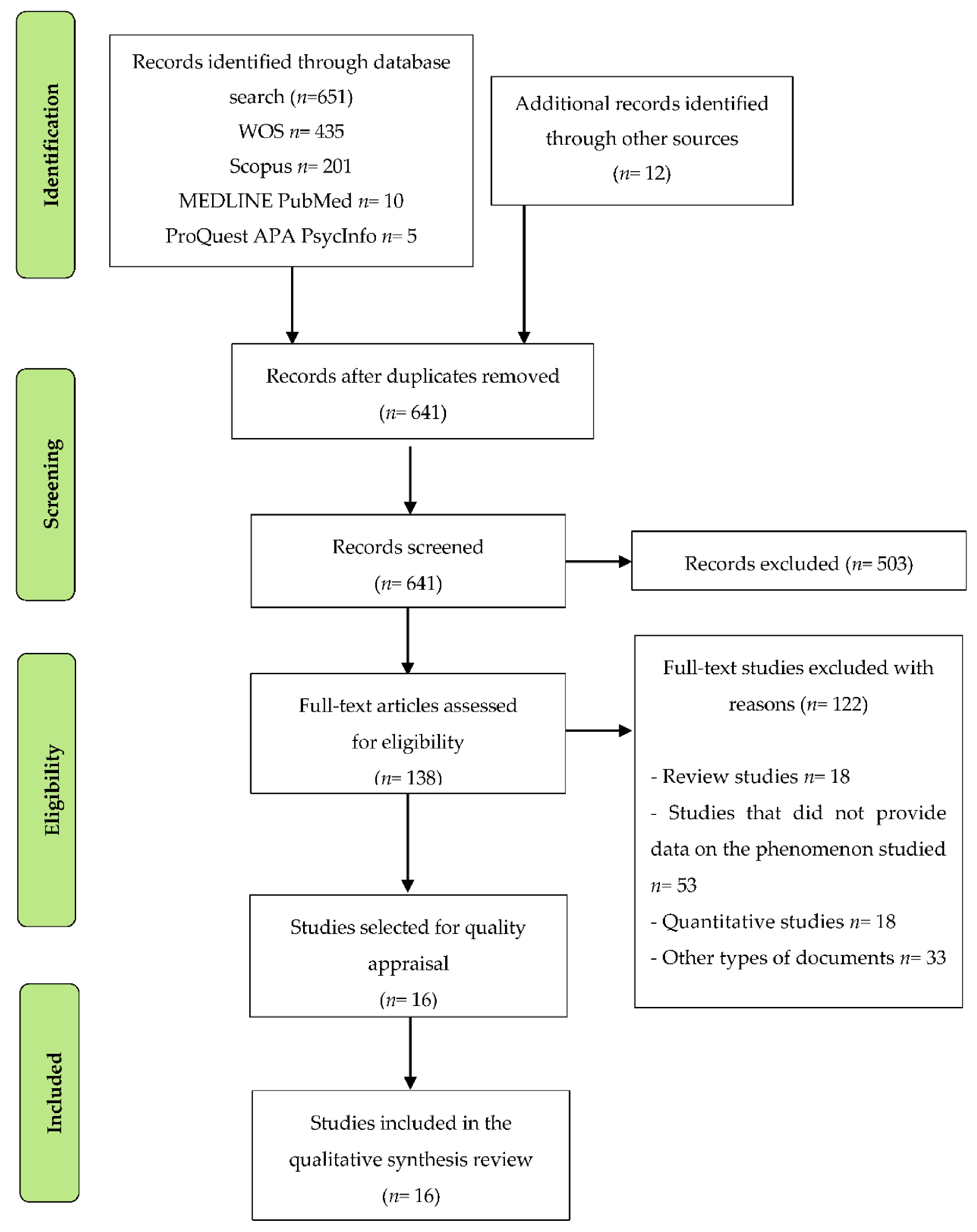

4.1. Results of the Bibliographic Search

4.2. Studies Included and Their Characteristics

4.3. Results of the Assessment of the Methodological Quality

4.4. Emerging Themes from the Thematic Analysis

- (A)

- The motivational autonomy of the disabled traveler;

- (B)

- Accessible tourism is a real business opportunity;

- (C)

- Exclusive tourism versus inclusive tourism with feedback (summative evaluation of the tourism experience).

4.4.1. The Motivational Autonomy of the Disabled Traveler

“I think it’s because in everyday life, disabled people depend so much on the help of others and that makes it difficult for them to be free to decide things”.[48]

“Once I needed to travel for a long distance and it involved taking a flight. My mother tried to stop me from going and said it was very dangerous. She was so worried that she could not sleep for a few nights. Eventually, I did not go, as she had influenced my decision”.[88]

4.4.2. Accessible Tourism Is a Real Business Opportunity

4.4.3. Exclusive Tourism Versus Inclusive Tourism with Feedback (Summative Evaluation of the Tourism Experience)

5. Discussion

Limitations and Implications

- (1)

- Hypersegmentation—assess which tourism providers can offer a better service. The aim is to offer a personalized, authentic experience that can be shared.

- (2)

- Analyze the tourism environment—make sure that the space where the tourism service offered is safe, friendly, and usable by the traveler.

- (3)

- Train the human resources that staff the tourist resort.

- (4)

- Provide accurate information about the service and everything related to it, including transportation, nearby facilities, etc. All travelers value information on the services they hire, and in the case of people with a disability, information is even more important.

- (5)

- Analyze whether the website is accessible to everyone. In addition to providing accurate and complete information on services and facilities for people with disabilities, we must ensure that content is accessible to all travelers.

- (6)

- Ask travelers to rate their experience.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Characteristics of the Studies Included, Extracted Using the Recommendations of the Interpretive and Critical Research Form

| Author and Year | Methods for Data Collection and Analysis | Country | Phenomena of Interest | Setting/Context/Culture | Participants Characteristics and Sample Size | Description of Main Findings | Classification of Quality/Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blichfeldt & Nicolaisen (2011) [48] | In-depth interviews and focus group interview. Extensive ideographic analysis. | Denmark | Reflections on the efforts that tourists with disabilities have to face, as well as their motivations and vacation decision-making. | Rural and urban setting in Denmark | Total (n = 21) 10 respondents and 11 experts Sex: 16-F 5-M Ages: 27–67 | Disabled tourists go on holiday primarily to escape from their role as care receivers. Decision-making while on holiday is much more complex for disabled tourists than for other tourists. | High (7) |

| Bowtell (2015) [13] | In-depth semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis. | Different European countries | Analysis of the potential of the accessible tourism market. Reasons for companies to participate in or avoid the accessible tourism market. | Formal context. Leading accessible tourism provider companies in Europe | Total (n = 12) Travel and leisure companies Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | The main findings of this study highlight that the accessible tourism market has a great capacity for future growth. This can become a potentially substantial and lucrative market. | Moderate (6) |

| Buhalis & Michopoulou (2011) [3] | 16 focus groups. Content analysis. | United Kingdom and Greece | Segmentation of the accessibility market. The usefulness of ICTs to end this segmentation through the use of profiles that allow tourists to personalize their demands and specify their requirements. | London, UK and Athens, Greece. European experts from 17 countries | Total (n = 199) Workshop in London with 68 participants. Workshop in Athens with 131 participants. Sex: Not specified. Ages: 18–65 | ICTs become a key tool for companies to effectively address the particular requirements of travelers with specific needs, through the creation of profiles and personalization. This information is systematized and as a result, companies can offer products and services that are appropriate to the needs of each traveler and encourage their participation. | High (8) |

| Capitaine (2016) [78] | In-depth interviews; open-ended and closed-ended questions. Data analyzed thematically using iterative coding. | Quebec (Canada) | How to encourage accommodation managers to implement accessibility in their businesses. | Respondents from various geographical origins: Countryside (40%)/Urban Center (40%)/Suburbs (20%) | Total (n = 30) (Manager; Executive directors; Owner; Director;) Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | Respondents showed interest in the field of accessibility, which they view as a means of increasing bookings at their hotels. However, they exhibit low levels of knowledge about this type of clientele, the concept of accessibility and the facilities that tourism without barriers requires. | High (8) |

| Eichhorn, Miller, Michopoulou and Buhalis (2008) [79] | Surveys via telephone and email (with open and closed questions). Exploratory research. | United Kingdom and Greece | Keys to accessible and quality information and communication in accessible tourism. Relationships between accessibility schemes in communication and their potential to satisfy the information needs of disabled tourists. | Formal-academic context. Conferences on accessible tourism in London, United Kingdom, and Athens, Greece | Total (n = 43) Tourist providers. Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | A more sophisticated understanding of the different needs (PwD) and appropriate sources is required. Tourist participation and their ability to enjoy its broader social benefits depend on the quality of the providers’ performance in terms of communication sources. | Moderate (6) |

| Eichhorn, Miller, and Tribe (2013) [80] | Semistructured, in-depth interview. Thematic analysis. Research guided by critical theory. | United Kingdom | Resistance strategies in people with disabilities. The role of tourism as an opportunity to develop a sense of one’s own identity. | Analysis of the contextual differences between the home and outdoor spaces | Total (n = 34) 18 persons with a visual impairment and 16 with a mobility impairment. Sex: 19-F 15-M Ages: 18–70 | The results of this study show that there is a dichotomy between strategies that allow or hamper resistance. Tourism offers the opportunity to develop a sense of identity, highlighting the refusal to resort to specialized operators. | High (10) |

| Gillovic and McIntosh (2015) [41] | Semistructured interviews Interpretive paradigm. Thematic analysis. | New Zealand | Determine the challenges the tourism industry is facing, as well as its ability to overcome them and achieve a future for accessible tourism in New Zealand. | Professional context. Experts and people in the accessible tourism market | Total (n = 10) Key stakeholders. Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | Stakeholders showed minimal awareness of accessibility. Accessibility was understood as a social issue that required a cultural change for a promising future. | Moderate (6) |

| Imrie and Kumar (1998) [81] | 4 focus groups. Thematic analysis. | England | Experiences, needs and requirements of people with disabilities in relation to their accessibility to build environments. | Two small coastal towns in England, Weymouth and Gateshead | Total (n = 30) 12 people with physical disabilities (using a wheelchair); 7 visually impaired; 6 with hearing impairment and 5 with walking difficulties. Sex: 14-F 16-M | The needs of PwD are poorly articulated or represented both in the design and in the finished environment. PwD feel separated and oppressed by aspects of the environment, and feel powerless about it. | Low (3) |

| Kim, Stonesifer, and Han (2012) [82] | Semistructured, in-depth interviews. Data triangulation. | United States of America | Identification of needs and perceptions of guests with disabilities in relation to their experiences at the hotel. Analysis of the feasibility to carry out their suggestions in the design of the hotel and its service policies. | Major cities in Florida | Total (n = 9) Guests with mobility impairments Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | Responses from guests with disabilities offer suggestions and express needs for special accommodations. PwD request more sensitivity training from hotel managers and workers. | High (10) |

| McKercher, Packer, Yau, and Lam (2003) [83] | Focus groups and in-depth interviews. Exploratory research model. | China | Perceptions of people with disabilities on the effectiveness of travel agencies. | Hong Kong urban context, disabled people | Total (n = 52) People with mobility and visual impairments. Sex: Not specified Ages: 24–70 | There is discrimination regarding information on tourism products and services for PwD. The need for tour agents to promote travel is underscored. | High (7) |

| Navarro, Andreu, and Cervera (2014) [84] | In-depth interviews. Exploratory data analysis. | Spain | The value of co-creation in tourism companies. How can people with disabilities contribute? | Hotel industry in a Spanish city on the Mediterranean coast | Total disabled tourists = 10 Sex: 5-F 5-M Total hotel managers = 6 Ages: 30–60 Total (n = 16) | The help of this co-creation in increasing the benefits for participants is highlighted. | Moderate (6) |

| Nicolaisen, Blichfeldt, and Sonnenschein (2012) [85] | Semistructured, in-depth interviews. Data analyzed thematically using case-ordered metamatrixes. | Denmark and Germany | The importance of perceptions from the supply side to guarantee the quality of accessible tourism. | Two national contexts: Denmark and Germany. National context of researchers. Four nonarbitrarily selected cases. | Total (n = 84) Tourism providers Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | The results of this study indicate that to facilitate leisure for people with disabilities, it is not enough to follow one model of disability or another (medical or social models). The truth is that this is a more complex task that depends rather on: following a more systemic approach to accessible tourism; Implications of further research on accessible tourism and tourism providers. | Moderate (6) |

| Nyanjom, Boxall, and Slaven (2018) [39] | In-depth interviews. Thematic approach. Triangulation process. | Australia | Stakeholder collaboration for the development of accessible tourism. | Rural context. Specifically, it focuses on Margaret River, a city in the south-west of Western Australia. | Total (n = 18) People with disabilities; Organizations of people with disabilities; H&T service providers; Government agencies Sex: 9-F 9-M Ages: 20–70 | To achieve accessible tourism when there are multiple actors, it is necessary to adopt a circulatory approach of development and collaboration. For this, the authors consider it necessary to develop a framework that takes into account; -Control and coordination, communication, clarity in roles and responsibilities, and collaboration and integration. | High (8) |

| Packer, McKercher, and Yau (2007) [86] | Naturalistic inquiry using key informant interviews and focus groups. | China | Difficulties and problems for PwD to participate in tourism, from their own perceptions. | Known groups of Hong Kong tourism consumers | Total (n = 86) Disabled tourists Sex: 49-F 37-M Ages: Not specified | A reciprocal relationship can be observed between the context of the trip and the process of becoming or staying active in it. The process of becoming an active traveler comprises six stages, where environmental and personal factors contribute to the explanation of the complex relationship between tourism, disability and environmental contexts. | Moderate (6) |

| Patterson, Darcy, andMönninghoff (2012) [87] | Semistructured, in-depth interviews. Thematic analysis. | Australia | Attitudes and experiences of Australian tour operators in relation to the provision of services and products to tourists with disabilities. | Northern Australia. More specifically in the state of Queensland. | Total (n = 32) Tourism operators Sex: Not specified Ages: Not specified | Accessibility to public transport and tourist attractions in the state of Queensland has improved and this has significant financial implications. Tour operators are making a significant effort to make their products and services more accessible. The motivational aspects identified to improve accessibility include greater availability of financial support and more moral, personal and emotional rewards. | Moderate (6) |

| Yau, Mckercher, and Packer (2004) [88] | In-depth interviews and focus groups. Thematic content analysis. | China | Tourism needs and experiences of people with physical or visual disabilities. | Formal context, the participants came from various organizations representing persons with disabilities in Hong Kong. | Total (n = 52) Participants with either a mobility disability or a visual impairment. Sex: 17-F 35-M Ages: 24–72 | The qualitative results indicate that travelers with disabilities undergo five stages to become active travelers (personal, reconnection, tourism analysis, physical travel and experimentation and reflection). If tourism providers and the rest of the population understand these stages better, a greater awareness of the tourism needs of people with disabilities can be achieved. | Moderate (5) |

References

- World Health Organization. Disability and health; World report on disability; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70670/WHONMHVIP11.01eng.pdf;jsessionid=2D8929CFD48138CC426E046401D842F5?sequence=1 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- World Tourism Organization. A United Nations Specialized Agency (2019). Accessible Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/accessibility (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Buhalis, D.; Michopoulou, E. Information-enabled tourism destination marketing: Addressing the accessibility market. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Velasco, D.J. El Mercado Potencial del Turismo Accesible Para el Sector Turístico Español; Accesturismo: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh, S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Available online: https://www.bts.gov/topics/passenger-travel/travel-patterns-american-adults-disabilities (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Zheng, X.; Chen, G.; Song, X.; Liu, J.; Yan, L.; Du, W.; Pang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, B.; et al. Twenty-year trends in the prevalence of disability in China. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Human Rights Research Society. Available online: http://www.humanrights.cn/html/2017/50601/28053.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- China Disable Person’s Federation. Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/sjzx/cjrgk/201206/t20120626387581.shtml (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Tao, B.C.; Goh, E.; Huang, S.; Moyle, B. Travel constraint perceptions of people with mobility disability: A study of Sichuan earthquake survivors. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Pavkovic, I.; Lawrie, A.; Farrell, G.; Huuskes, L.; Ryan, R. Inclusive Tourism: Economic Opportunities; University of Technology Sydney Institute for Public Policy and Governance: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- New Zeland Tourism. About the Tourism Industry. Available online: https://www.tourismnewzealand.com/about/about-the-tourism-industy/#:~:text=For%20the%20year%20ended%20March,exports%20of%20goods%20and%20services (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Bowtell, J. Assessing the value and market attractiveness of the accessible tourism industry in Europe: A focus on major travel and leisure companies. J. Tour. Future 2015, 1, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T.J. A whole-of-life approach to tourism: The case for accessible tourism experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 16, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühretmair, F. People with Disabilities: Accessible Tourism Introduction to the Special Thematic Session. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Klaus, J., Zagler, W.L., Karshmer, A.I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, Y.; Yayli, A.; Yesiltas, M. Is the Turkish tourism industry ready for a disabled customer’s market? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Card, J.A.; Cole, S.T. Accessibility and attitudinal barriers encountered by Chinese travellers with physical disabilities. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Card, J.A. U.S. Tour Operators and Travel Agencies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramanayagam, S.; Seal, P.P.; More, B. Inclusive hotel design in India: A user perspective. J. Access. Des. All 2019, 9, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, R.; Scheyvens, R. Introducing inclusive tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Moreno, D.C. Tecnologías de información y comunicación para el turismo inclusivo. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Económicas 2017, 26, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.L.; Chan, C.-S.; Peters, M. Understanding technological contributions to accessible tourism from the perspective of destination design for visually impaired visitors in Hong Kong. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, N.; Amin, M.; Chan, S.; Aprilia, C. How smart tourism technologies affect tourist destination loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Pegg, S. Towards Strategic Intent: Perceptions of disability service provision amongst hotel accommodation managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.O. Which accessible travel products are people with disabilities willing to pay more? A choice experiment. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorková, D. The issue of accessibility from the point of view of tourism service providers. Ekon. Rev. Cent. Eur. Rev. Econ. Issues 2016, 19, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajadacz, A. Evolution of models of disability as a basis for further policy changes in accessible tourism. J. Tour. Futur. 2015, 1, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutuncu, O. Investigating the accessibility factors affecting hotel satisfaction of people with physical disabilities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, C. Ming. The influence of accessibility and motivation on leisure travel participation of people with disabilities. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J. The hidden side of travel: Epilepsy and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.J.; Drogin Rodgers, E.B.; Wiggins, B.P. “Travel Tales”: An interpretive analysis of constraints and negotiations to pleasure travel as experienced by persons with physical disabilities. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgley, D.; Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N.; Hanna, P. Tourism and autism: Journeys of mixed emotions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Micera, R. The experience co-creation in smart tourism destinations: A multiple case analysis of European destinations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 16, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou, E.; Buhalis, D. Information provision for challenging markets: The case of the accessibility requiring market in the context of tourism. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Castellani, P.; Rossato, C.; Baccarani, C. Finding a way towards high-quality, accessible tourism: The role of digital ecosystems. TQM J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, U.S.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devile, E.; Kastenholz, E. Accessible tourism experiences: The voice of people with visual disabilities. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2018, 10, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratucu, G.; Chitu, I.B.; Dinca, G.; Stefan, M. Opinions of tourists regarding the accessibility for people with disabilities in the area of Braşov County. Transilv. Univ. Brasov 2016, 9, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanjom, J.; Boxall, K.; Slaven, J. Towards inclusive tourism? Stakeholder collaboration in the development of accessible tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. Accessible tourism in Jordan: Travel constrains and motivations. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 10, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gillovic, B.; McIntosh, A. Stakeholder perspectives of the future of accessible tourism in New Zealand. J. Tour. Futur. 2015, 1, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Cameron, B.; Pegg, S. Accessible tourism and sustainability: A discussion and case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, T.D.; Darcy, S.; González, E.A. Competing for the disability tourism market—A comparative exploration of the factors of accessible tourism competitiveness in Spain and Australia. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S. Inherent complexity: Disability, accessible tourism and accommodation information preferences. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. The relationship between the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of a tourist destination: The role of nationality—An analytical qualitative research approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Gilbert, D. Tourism Constraints: The Neglected Dimension in Consumer Behaviour Research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 8, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillovic, B.; McIntosh, A. Accessibility and Inclusive Tourism Development: Current State and Future Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B.S.; Nicolaisen, J. Disabled travel: Not easy, but doable. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Figueiredo, E. Contributions of tourism to social inclusion of persons with disability. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 1259–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Eusébio, C.; Kastenholz, E. How Diverse Are Tourists with Disabilities? A Pilot Study on Accessible Leisure Tourism Experiences in Portugal. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.M.; Ryder, M.E. “Ebilities” tourism: An exploratory discussion of the travel needs and motivations of the mobility-disabled. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenko, Z.; Sardi, V. Systemic thinking for socially responsible innovations in social tourism for people with disabilities. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumbo, N.J.; Pegg, S. Travelers and Tourists with Disabilities: A Matter of Priorities and Loyalties. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 8, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.; Åhman, H.; Yngling, A.A.; Gulliksen, J. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—one goal? On the concept of accessibility—historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloquet, I.; Palomino, M.; Shaw, G.; Stephen, G.; Taylor, T. Disability, social inclusion and the marketing of tourist attractions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, F. Inclusive tourism: A priority for Portugal. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B. Innovation through Co-creation: Towards an Understanding of Technology-Facilitated Co-Creation Processes in Tourism. In Open Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, S.; Cercera, A.; Andreu, L.; Cervera Taulet, A.; Andreu Simó, L. Key factors in value co-creation for disabled customers and hotel services. An exploratory study of hotel managers. Rev. Análisis Turístico 2015, 20, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J. Has tourism the resources and answers to a more inclusive society? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, T.; Fraiz, J.A.; Alén, E. Economic Profitability of Accessible Tourism for the Tourism Sector in Spain. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Casaccia, M.; Garofalo, A.; Marchesano, K. Tourism and disability in Italy. Limits and opportunities. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L.; Moura, A.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. The Relevance of Internet as an Information Source on the Accessible Tourism Market. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism, Technology and Systems, Cartagena, Colombia, 29–31 October 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Vila, T.; Alén González, E.; Darcy, S. Accessible tourism online resources: A Northern European perspective. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo-Martínez, D.; Sánchez-Aarnoutse, J.-C.; Carrillo-de-Gea, J.M.; García-Berná, J.A.; Fernández-Alemán, J.L.; García-Mateos, G. Design and Development of a Mobile App for Accessible Beach Tourism Information for People with Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibanescu, B.-C.; Eva, M.; Gheorghiu, A. Questioning the Role of Tourism as an Engine for Resilience: The Role of Accessibility and Economic Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letelier, L.M.; Manríquez, J.J.; Rada, G. MEDICINA BASADA EN EVIDENCIA Revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis: ¿son la mejor evidencia? Rev. Méd. Chile 2005, 133, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Grp, P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780470712184. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; ISBN 9780648848806. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C.; Porrit, K.; Munn, Z.; Rittenmeyer, L.; Salmond, S.; Bjerrum, M.; Loveday, H.; Carrier, J.; Stannard, D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Brunton, J.; Graziosi, S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: Software for Research Synthesis; EPPI-Center Software; Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare BV Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Fullen, B.M.; Baxter, G.D.; O’Donovan, B.G.G.; Doody, C.; Daly, L.; Hurley, D.A. Doctors’ attitudes and beliefs regarding acute low back pain management: A systematic review. Pain 2008, 136, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoy-Cano, A.J.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Fuente-Robles, Y.M.D. La Factors Conditioning Sexual Behavior in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitaine, V. Inciting tourist accommodation managers to make their establishments accessible to people with disabilities. J. Tour. Futur. 2016, 2, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, V.; Miller, G.; Michopoulou, E.; Buhalis, D. Enabling access to tourism through information schemes? Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, V.; Miller, G.; Tribe, J. Tourism: A site of resistance strategies of individuals with a disability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R.; Kumar, M. Focusing on disability and access in the built environment. Disabil. Soc. 1998, 13, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Stonesifer, H.W.; Han, J.S. Accommodating the needs of disabled hotel guests: Implications for guests and management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Packer, T.; Yau, M.K.; Lam, P. Travel agents as facilitators or inhibitors of travel: Perceptions of people with disabilities. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Andreu, L.; Cervera, A. Value co-creation among hotels and disabled customers: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaisen, J.; Blichfeldt, B.S.; Sonnenschein, F. Medical and social models of disability: A tourism providers’ perspective. World Leis. J. 2012, 54, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, T.L.; Mckercher, B.; Yau, M.K. Understanding the complex interplay between tourism, disability and environmental contexts. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, I.; Darcy, S.; Mönninghoff, M. Attitudes and experiences of tourism operators in Northern Australia towards people with disabilities. World Leis. J. 2012, 54, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, M.K.S.; McKercher, B.; Packer, T.L. Traveling with a disability: More than an Access Issue. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Manual Sobre Turismo Accesible para Todos: Principios, Herramientas y Buenas Prácticas—Módulo I: Turismo Accesible—Definición y Contexto; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 9789284416486.

- Popiel, M. Bariery w podejmowaniu aktywności turystycznej przez osoby niepełnosprawne. Barriers Tour. People Disabil. 2016, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-E. Understanding the Discrimination Experienced by Customers with Disabilities in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry: The Case of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart Tourism Destinations Enhancing Tourism Experience through Personalisation of Services. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Özogul, G.; Baran, G.G. Accessible tourism: The golden key in the future for the specialized travel agencies. J. Tour. Futur. 2016, 2, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, J.F.P.; Rodríguez, A.R.; Jiménez, M.S. Determinants of the Competitive Advantage of Residential Tourism Destinations in Spain. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, N.; Rucci, A.C.; Ciaschi, M. Tourism accessibility competitiveness. A regional approach for Latin American countries. Investig. Reg. 2019, 2019, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Figueiredo, E.; Lima, J. Accessibility as Competitive Advantage of a Tourism Destination: The Case of Lousã. In Field Guide to Case Study Research in Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; pp. 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Daruwalla, P.; Darcy, S. Personal and societal attitudes to disability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Santamaria, E.K.; Operario, D.; Tarkang, E.E.; Zotor, F.B.; Cardoso, S.R.D.S.N.; Autor, S.E.U.; De, I.; Dos, A.; Vendas, O.D.E.; et al. Analysis of the co-distributed structure of health-related indicators in the elderly with a focus on subjective health. BMC Public Health 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bizjak, B.; Knežević, M.; Cvetrežnik, S. Attitude change towards guests with disabilities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Garzón, D.; Roig-Tierno, N. Co-creation in hotel–disable customer interactions. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.I.; Ye, S.; Wang, D.; Law, R. Engaging Customers in Value Co-Creation Through Mobile Instant Messaging in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | Search 1 WOS: (TOPIC: ((“accessible tourism” OR “adapted tourism” AND “people with disability” OR “disabled persons” OR “hotel managers” OR “tourism experts” AND “perceptions” OR “feelings” OR “views” AND “tourism economy” OR “tourism market industry” AND “quality of accessible tourism”)) |

| Scopus | Search 1 Scopus: [title-abs-key (“accessible tourism” OR “adapted tourism”) AND (“people with disability” OR “disabled persons” OR “hotel managers” OR “tourism experts”) AND (“perceptions” OR “feelings” OR “views”)] |

| MEDLINE PubMed | Search 1 PubMed: (accessible tourism[mh] OR accessible tourism[tiab]) AND (people with disability[mh] OR disabled persons[tiab] OR hotel managers[mh] OR tourism experts[tiab]) |

| ProQuest APA PsycInfo | Search 1 PsycInfo: (accessible tourism OR adapted tourism) AND (people with disability OR disabled persons OR hotel managers OR tourism experts) AND (perceptions OR feelings OR views) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuente-Robles, Y.M.D.L.; Muñoz-de-Dios, M.D.; Mudarra-Fernández, A.B.; Ricoy-Cano, A.J. Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410507

Fuente-Robles YMDL, Muñoz-de-Dios MD, Mudarra-Fernández AB, Ricoy-Cano AJ. Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410507

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuente-Robles, Yolanda María De La, María Dolores Muñoz-de-Dios, Ana Belén Mudarra-Fernández, and Adrián Jesús Ricoy-Cano. 2020. "Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410507

APA StyleFuente-Robles, Y. M. D. L., Muñoz-de-Dios, M. D., Mudarra-Fernández, A. B., & Ricoy-Cano, A. J. (2020). Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Sustainability, 12(24), 10507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410507