Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy: A Comparative Study of Airbnb Online Reviews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy

2.2. User-Generated Content as a Resource for Accommodation Experience Research

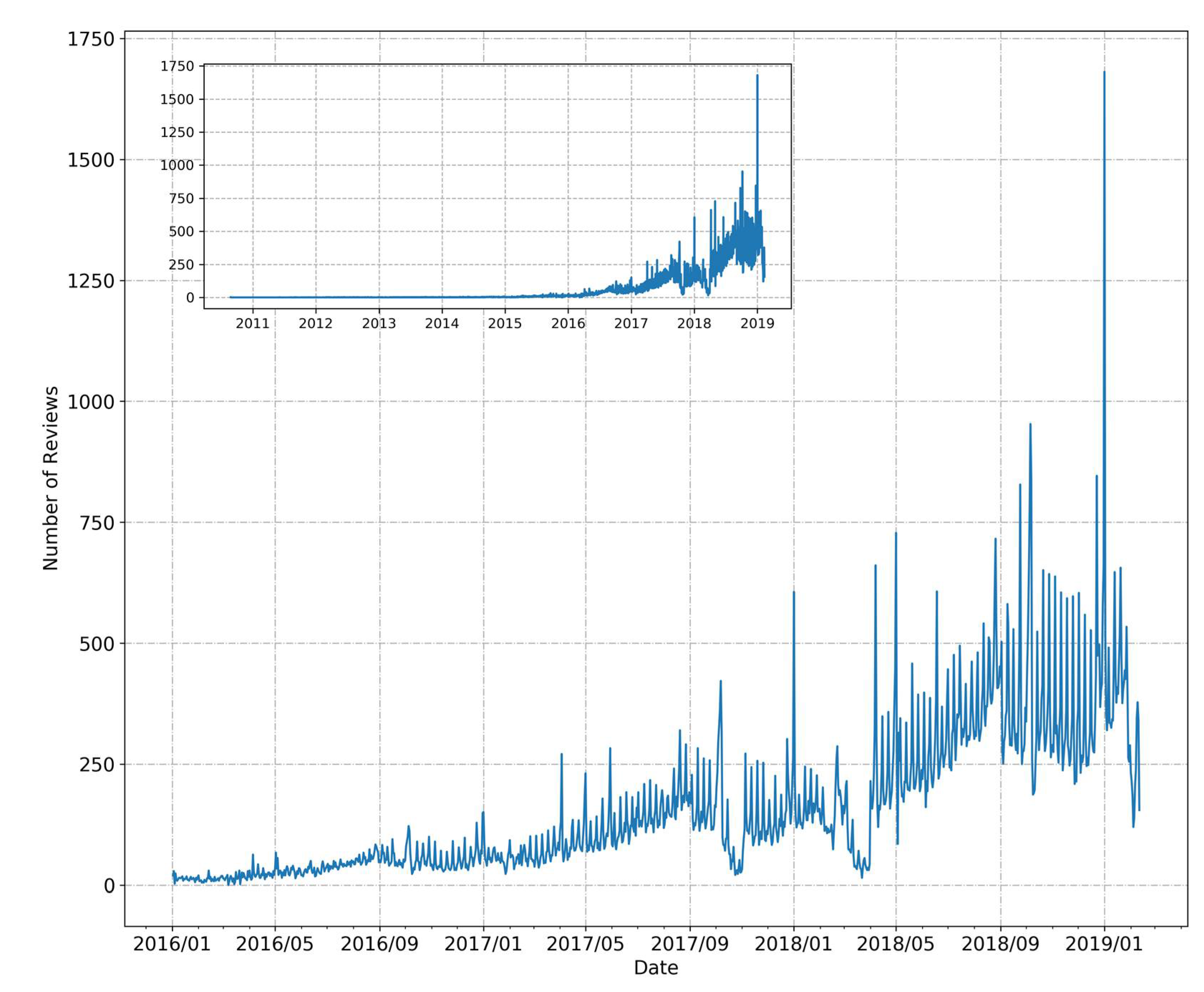

3. Data and Methodology

- Choose , where is the length of the document ;

- Choose for a document’s topic distribution, where is the -vector parameter of the Dirichlet prior to the per-document topic distributions;

- For each of the words for document :

- Choose a topic ;

- Choose a word from , a multinomial probability conditioned on the topic , where is a parameter of the Dirichlet prior on the per-topic word distribution.

4. Results

4.1. Dimensions Extracted from Airbnb Reviews

4.2. Dimension Comparison between Domestic Guests and Foreign Guests

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fu, R.J.; Han, L.D.; Yang, L. Key Factors Affecting the Price of Airbnb Listings: A Geographically Weighted Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Airbnb. Fast Facts. Available online: https://press.airbnb.com/fast-facts/ (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- Lampinen, A.; Cheshire, C. Hosting via Airbnb: Motivations and financial assurances in monetized network hospitality. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 1669–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleo, L.; Romolini, A.; De Marco, M. The Sharing Economy Revolution and Peer-to-Peer Online Platforms. The Case of Airbnb; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 247, pp. 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ert, E.; Fleischer, A.; Magen, N. Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Jung, J.H.; Ryu, S.Y.; Kim, S.D.; Yoon, S.-M. The Relationship between Airbnb and the Hotel Revenue: In the Case of Korea. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Pan, Q.; Yang, T.; Guo, L. Reasonable price recommendation on Airbnb using Multi-Scale clustering. In Proceedings of the 2016 35th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chengdu, China, 27–29 July 2016; pp. 7038–7041. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Nicolau, J.L. Price determinants of sharing economy based accommodation rental: A study of listings from 33 cities on Airbnb.com. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 62, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Fu, R.J. Assessing Airbnb Logistics in Cities: Geographic Information System and Convenience Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutiérrez, J.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Romanillos, G.; Salas-Olmedo, M.H. The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: Comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Rahimi, R.; Vedanthachari, L.N. Unraveling the diverse nature of service quality in a sharing economy: A social exchange theory perspective of Airbnb accommodation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2279–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Jin, X. What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tang, R. Understanding hidden dimensions in textual reviews on Airbnb: An application of modified latent aspect rating analysis (LARA). Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.R.; Jeong, M. What makes you choose Airbnb again? An examination of users’ perceptions toward the website and their stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Jiménez-Barreto, J. Exploring tourists’ memorable hospitality experiences: An Airbnb perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.J.; Lee, H.; Suh, E.-K.; Suh, K.-S. Shared experience in pretrip and experience sharing in posttrip: A survey of Airbnb users. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R. Examination of motivations and attitudes of peer-to-peer users in the accommodation sharing economy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, J.M.; Del Chiappa, G.; Sini, L. Booking experiences on sharing economy platforms: An exploration of tourists’ motivations and constraints. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.A.; Suess, C.; Lehto, X. The accommodation experiencescape: A comparative assessment of hotels and Airbnb. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2377–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A.; Whalen, E.; Koh, Y.; Bowen, J.T. Comparing guests’ key attributes of peer-to-peer accommodations and hotels: Mixed-methods approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cui, R.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. A comparison of key attributes between peer-to-peer accommodations and hotels using online reviews. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, H.; Berezina, K.; Cobanoglu, C. Comparing customer perceptions of hotel and peer-to-peer accommodation advantages and disadvantages. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1190–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, R.; Cheng, M. Peer-to-peer accommodation experience: A Chinese cultural perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Park, J. Experience co-creation in the P2P accommodation sharing sector in China. In CAUTHE 2020: 20: 20 Vision: New Perspectives on the Diversity of Hospitality, Tourism and Events; Auckland University of Technology: Auckland, New Zeeland, 2020; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Miao, L.; Huang, Z.J. Customer engagement behaviors and hotel responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, M.; McGuire, K.; Cleveland, C. Let me count the words: Quantifying open-ended interactions with guests. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ye, S.; Pearce, P.L.; Wu, M.-Y. Refreshing hotel satisfaction studies by reconfiguring customer review data. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda, A.; Bilgihan, A. An analysis of user-generated content for hotel experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2013, 4, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Troilo, M.; Shah, A. Airbnb customer experience: Evidence of convergence across three countries. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Qiu, H.; Ma, C.; Linc, P. Investigating accommodation experience in budget hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2662–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Huang, S.; Shen, G. Modelling Chinese consumer choice behavior with budget accommodation services. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Relative Weight | Topic | Relative Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 1: Amenities | Topic 2: Availability/public transportation | ||

| water | 1.6% | (convenient) | 5.9% |

| bathroom | 1.6% | (station) | 4.1% |

| room | 1.4% | (subway) | 2.6% |

| shower | 1.2% | (apartment) | 2.4% |

| apartment | 1.2% | (nearby) | 2.0% |

| kitchen | 1.1% | (downstairs) | 1.9% |

| toilet | 1.1% | (close) | 1.8% |

| floor | 0.9% | (house) | 1.7% |

| building | 0.8% | (location) | 1.7% |

| towel | 0.8% | (distance) | 1.5% |

| small | 0.7% | (room) | 1.4% |

| host | 0.7% | (transportation) | 1.4% |

| like | 0.7% | (grocery) | 1.4% |

| door | 0.6% | (minutes) | 1.4% |

| bedroom | 0.6% | (walking) | 1.2% |

| Dimension | Top 10 Words for Each Dimension |

|---|---|

| Convenience/Location | place, Beijing, great, stay, location, good, city, close, nice, perfect |

| Amenities | water, bathroom, room, shower, apartment, kitchen, toilet, floor, building, towels |

| Feel at home | Beijing, home, stay, place, best, time, feel, apartment, like, great |

| Check-in/out | check, host, late, airport, stay, arrive, time, night, early, good, helped |

| Experience | house, Beijing, experience, nice, room, hutong, like, good, time, living |

| Availability/Transportation | subway, station, apartment, walk, close, restaurant, location, place, convenient, metro |

| Host | good, room, location, place, apartment, host, nice, Airbnb, great, English |

| Style/Decoration | place, stay, flat, space, great, quiet, decoration, enjoy, cool, lovely |

| Recommendation | great, place, nice, stay, clean, location, amazing, helpful, recommend, friendly |

| Booking flexibility | arrival, host, reservation, automated, cancel, posting, days, promise, helpful, alarm |

| Dimension | Top 10 Words for Each Dimension |

|---|---|

| Convenience/Location | (Beijing), (alley), (convenient), (recommend), (travel), (attraction), (forbidden city), (recommendation), (nearby), (Tiananmen Square) |

| Amenities | (room), (bathroom), (kitchen), (air conditioner), (living room), (appliance), (towel), (toilet), (refrigerator), (washer) |

| Feel at home | (feeling), (homestay), (Beijing), (homeliness), (warm), (kids), (warm), (home), (at home), (satisfaction) |

| Check-in/out | (host), (check-in), (problem), (solve), (time), (response), (early), (in time), (communication), (contact) |

| Experience | (good), (room), (location), (clean), (cost-effective), (convenient), (comfortable) (overall), (entire), (satisfaction) |

| Availability/Transportation | (convenient), (station), (subway), (apartment), (nearby), (downstairs), (close), (house), (location), (distance) |

| Host | (host), (very), (dear), (lovely), (clean), (comfortable), (warm-hearted), (aunt), (considerable), (like) |

| Style/Decoration | (like), (style), (decoration), (room), (suitable), (design), (house), (careful), (happy), (arrangement) |

| Revisit | (next time), (Beijing), (host), (choose), (opportunity), (later), (stay), (definitely), (revisit), (again) |

| Cleanliness | (host), (room), (clean), (experience), (house), (warm-hearted), (tidy), (facility), (cozy), (satisfaction) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Fu, R.J.C. Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy: A Comparative Study of Airbnb Online Reviews. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410500

Zhang Z, Fu RJC. Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy: A Comparative Study of Airbnb Online Reviews. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410500

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhihua, and Rachel J. C. Fu. 2020. "Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy: A Comparative Study of Airbnb Online Reviews" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410500

APA StyleZhang, Z., & Fu, R. J. C. (2020). Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy: A Comparative Study of Airbnb Online Reviews. Sustainability, 12(24), 10500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410500