Residential Racial and Socioeconomic Segregation as Predictors of Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Neighborhood Effects of Housing Discrimination

1.2. Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area

- (1)

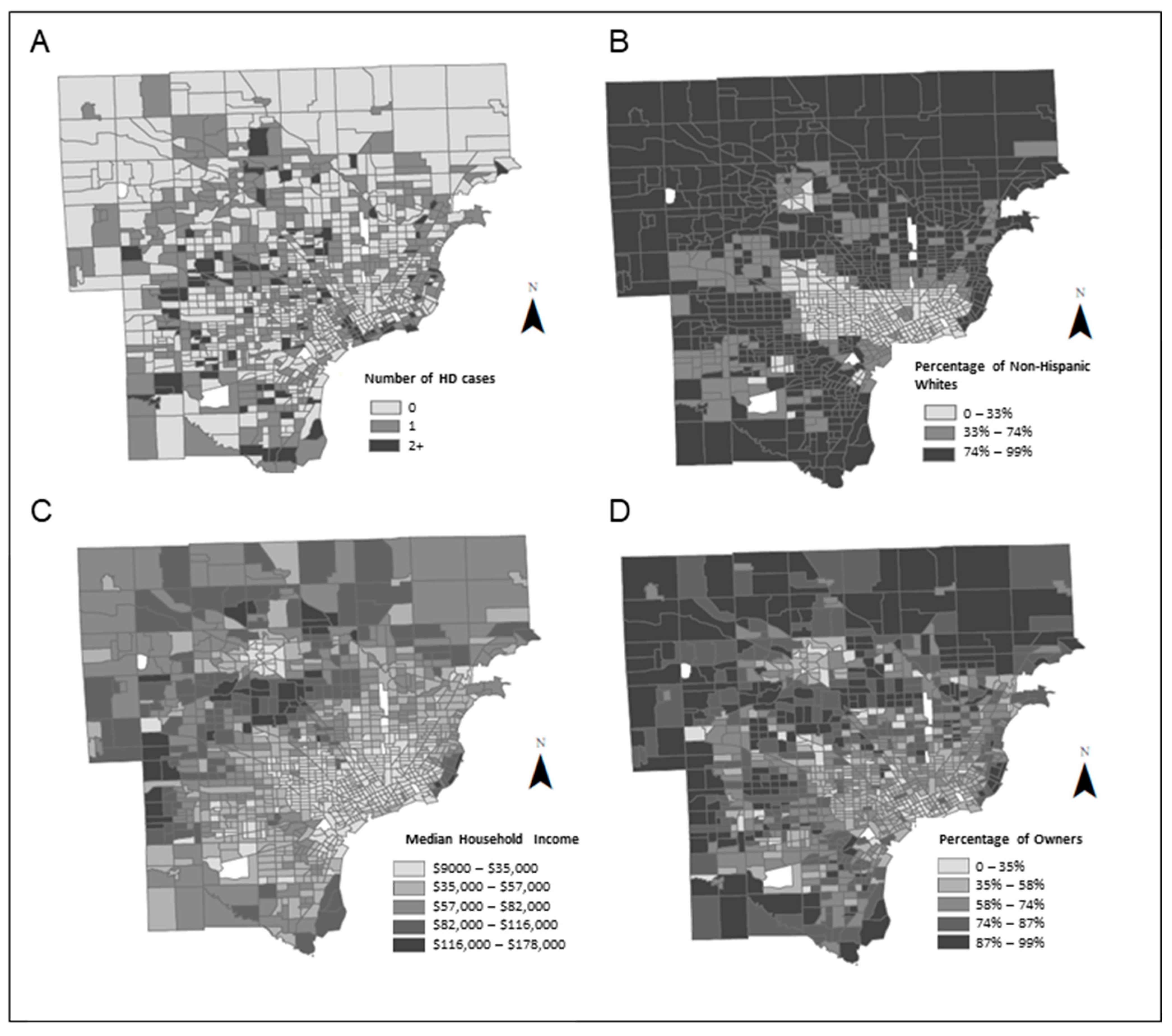

- Housing discrimination is more likely to occur in neighborhoods with higher percentage of non-Hispanic Whites;

- (2)

- Housing discrimination is more likely to occur in neighborhoods with higher median household incomes; and

- (3)

- Housing discrimination is more likely to occur in neighborhoods with a higher percentage of homeowners. Next, we tested the hypothesis that

- (4)

- each of these neighborhood characteristics contributes independently to an understanding of housing discrimination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Measures

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Housing and Neighborhood Stability and Housing Discrimination

4.2. Legacy of Redlining Practices

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson, M.; Petticrew, M.; Bambra, C.; Sowden, A.J.; Wright, K.E.; Whitehead, M. Housing and health inequalities: A synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place 2011, 17, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Schulz, A.J.; Israel, B.; Mentz, G.; Eisenberg, A.; Stokes, C.; Rowe, Z. Neighborhood context, homeownership and home value: An ecological analysis of implications for health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Fair Housing Act, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Pub. L. 90–284 (Apr. 11, 1968), as amended by Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100-430 (Sept. 13, 1988). The Fair Housing Act is codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601-3619. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-2 (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act, Act 452 of 1976, M.C.L. §§ 37.2501–37.2507. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/act_453_elliott_larsen_8772_7.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Detroit Code of Ordinances, Chapter 23 - Human Rights, Article VI - Real Estate, Insurance and Loan Practices, §§ 23-6-1 to 23-6-9. Available online: https://library.municode.com/mi/detroit/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIVDECO_CH23HURI (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- National Fair Housing Alliance. Making Every Neighborhood A Place of Opportunity: 2018 Fair Housing Trends Report. 2018. Available online: https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/NFHA-2018-Fair-Housing-Trends-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- National Fair Housing Alliance. 2019 Fair Housing Trends Report. 2019. Available online: https://nationalfairhousing.org/2019-fair-housing-trends-report/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Rohe, W.M.; Zandt, S.V.; McCarthy, G. Home Ownership and Access to Opportunity. Hous. Stud. 2002, 17, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abravanel, M.D. Do We Know More Now? Trends in Public Knowledge, Support and Use of Fair Housing Law. 2006. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/FairHousingSurveyReport.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Abravanel, M.; Cunningham, M.K. How Much Do We Know? Public Awareness of the Nation’s Fair Housing Laws. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/Publications/pdf/hmwk.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Galster, G. Urban Gentrification: Evaluating Alternative Indicators. Soc. Ind. Res. 1986, 18, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.L.; Turner, M.A. Housing Discrimination in Metropolitan America: Explaining Changes between 1989 and 2000. Soc. Probl. 2005, 52, 152–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinger, J. Housing discrimination is still worth worrying about. Hous. Policy Debate 1998, 9, 893–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymski, G.A. The theory of bank redlining and discrimination: An exploration. Rev. Black Politi-Econ 1995, 23, 37–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.A. Mortgage Lending Discrimination: A Review of Existing Evidence. Urban Institute. 1999. Available online: http://webarchive.urban.org/publications/309090.html (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Yinger, J. Measuring racial discrimination with fair housing audits: Caught in the act. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, G. The ecology of racial discrimination in housing: An exploratory model. Urban Aff. Q. 1987, 23, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D.J.; Cain, G.G. Statistical Theories of Discrimination in Labor Markets. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1977, 30, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, E.S. The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, 62, 659–661. [Google Scholar]

- Flage, A. Ethnic and gender discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a meta-analysis of correspondence tests, 2006–2017. J. Hous. Econ. 2018, 41, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; Constantine, P. Discrimination Against Female-Headed Households in Rental Housing: Theory and Exploratory Evidence. Rev. Soc. Econ. 1991, 49, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.; Swesnik, D. Discriminatory Effects of Credit Scoring on Communities of Color. Suffolk U. L. Rev. 2013, 46, 935. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L. African American Homeownership and the Dream Deferred: A Disparate Impact Argument against the Use of Credit Scores in Homeownership Insurance Underwriting. Conn. Ins. L.J. 2008, 15, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.; Lee, M. Why Place & Race Matter (Full Report). 2011. Available online: http://www.policylink.org/find-resources/library/why-place-and-race-matter (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Turner, M.A.; Santos, R.; Levy, D.K.; Wissoker, D.A. Housing Discrimination against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012: Full Report. Urban Institute. 2016. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/housing-discrimination-against-racial-and-ethnic-minorities-2012-full-report (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Myers, C.K. Discrimination and neighborhood effects: Understanding racial differentials in US housing prices. J. Urban Econ. 2004, 56, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, N.A. Segregation and Discrimination in Housing. In A Right to Housing: Foundation for a New Social Agenda; Bratt, R.G., Bratt, M.E., Hartman, C.W., Eds.; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno, V.J.; Karafin, D.L.; Tester, G. The complexities and processes of racial housing discrimination. Soc. Prob. 2009, 56, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugh, J.S.; Massey, D.S. Racial Segregation and the American Foreclosure Crisis. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.S.; Levine, P.B. Income Inequality, Social Mobility, and the Decision to Drop Out of High School (Brookings Paper on Economic Activity). 2016. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/kearneytextspring16bpea.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Reardon, S.F.; Owens, A. 60 Years After Brown: Trends and Consequences of School Segregation. Annu. Rev. Soc. 2014, 40, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Garcia, D.; Noelke, C.; McArdle, N.; Sofer, N.; Hardy, E.F.; Weiner, M.; Baek, M.; Huntington, N.; Huber, R.; Reece, J. Racial And Ethnic Inequities In Children’s Neighborhoods: Evidence From The New Child Opportunity Index 2.0. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbink, M.P.; Bader, M.D.M. Racial residential segregation and low birth weight in Michigan’s Metropolitan Areas. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Jesdale, B.M. Separate and unequal: Residential segregation and estimated cancer risks associated with ambient air toxics in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Environ. Health Perspect 2006, 114, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, K.D.; Kunitz, S.J.; Sell, R.R.; Mukamel, D.B. Metropolitan governance, residential segregation, and mortality among African Americans. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (5-Year Estimates). 2018. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2018/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Farley, R.; Danziger, S.; Holzer, H.J. Detroit Divided; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue, T.J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham, K.F. Racialization and the State: The Housing Act of 1934 and the Creation of the Federal Housing Administration. Sociol. Perspect. 2000, 43, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, J.T.; Hill, R.C.; Thomas, J.; Thomas, R. Detroit: Race and Uneven Development; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, S. Detroit’s Municipal Bankruptcy: Racialised geographies of austerity. New Political Economy 2018, 23, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A.; Mehdipanah, R.; Dewar, M. ‘It’s like they make it difficult for you on purpose’: Barriers to property tax relief and foreclosure prevention in Detroit, Michigan. Housing Studies 2020, 35, 1415–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University A New Decade of Growth for Remodeling: Improving America’s Housing. 2011. Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/2011_remodeling_color.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Dewar, M.; Seymour, E.; Druță, O. Disinvesting in the city: The role of tax foreclosure in Detroit. Urban Aff. Rev. 2015, 51, 587–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000. 2000. Available online: https://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Fair Housing Detroit (n.d.). Available online: http://www.fairhousingdetroit.org/ (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Schulz, A.J.; Zenk, S.; Kannan, S.; Israel, B.A.; Stokes, C. Community-based participatory approach to survey. In Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 197–223. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Environment Partnership (n.d.) Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Available online: http://www.hepdetroit.org/en/hep-overview/cbpr (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Mehdipanah, R.; Schulz, A.J.; Israel, B.A.; Gamboa, C.; Rowe, Z.; Khan, M.; Allen, A. Urban HEART Detroit: A tool to better understand and address health equity gaps in the city. J. Urban Health 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.J.; Zenk, S.; Odoms-Young, A.; Hollis-Neely, T.; Nwankwo, R.; Lockett, M.; Ridella, W.; Kannan, S. Healthy Eating and Exercising to Reduce Diabetes: Exploring the Potential of Social Determinants of Health Frameworks Within the Context of Community-Based Participatory Diabetes Prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, C. Fighting Housing Discrimination in 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/fighting-housing-discrimination-2019 (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Bentley, R.; Baker, E.; Mason, K.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kavanagh, A.M. Association between housing affordability and mental health: A longitudinal analysis of a nationally representative household survey in Australia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A.; Der, G.; Ford, G.; Hunt, K. Do housing tenure and car access predict health because they are simply markers of income or self esteem? A Scottish study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, S.E.; Zimmerman, F.J. Race/ethnicity and the relationship between homeownership and health. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e122–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblad, M.R.; Manturuk, K.R.; Quercia, R.G. Sense of Community and Informal Social Control Among Lower Income Households: The Role of Homeownership and Collective Efficacy in Reducing Subjective Neighborhood Crime and Disorder. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haurin, D.R.; Dietz, R.D.; Weinberg, B.A. The Impact of Neighborhood Homeownership Rates: A Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 303398). Social Science Research Network. 2002. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=303398 (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Ross, A.; Talmage, C.A.; Searle, M. Toward a Flourishing Neighborhood: The Association of Happiness and Sense of Community. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Housing Discrimination Under the Fair Housing Act. 2004. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/fair_housing_act_overview (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Akers, J.; Seymour, E. Instrumental exploitation: Predatory property relations at city’s end. Geoforum 2018, 91, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R. Housing as a Determinant of COVID-19 Inequities. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfer, E.; Robinson, D.B.; Butler, S.; Edmonds, L.; Gilman, S.; McKay, K.L.; Neumann, Z.; Owens, L.; Steinkamp, N.; Yentel, D. The COVID-19 Eviction Crisis: An Estimated 30-40 Million People in America Are at Risk. Available online: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/the-covid-19-eviction-crisis-an-estimated-30-40-million-people-in-america-are-at-risk/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Greiner, D.J.; Pattanayak, C.W.; Hennessy, J. The Limits of Unbundled Legal Assistance: A Randomized Study in a Massachusetts District Court and Prospects for the Future. Harv. L. Rev. 2012, 126, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porton, A.; Gromis, A.; Desmond, M. Inaccuracies in Eviction Records: Implications for Renters and Researchers. Hous. Policy Debate 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M.; Kimbro, R.T. Eviction’s fallout: Housing, hardship and health. Soc. Forces 2015, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Y.; Stenberg, S.-Å. Evictions and suicide: A follow-up study of almost 22,000 Swedish households in the wake of the global financial crisis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laere, I.; De Wit, M.; Klazinga, N. Preventing evictions as a potential public health intervention: Characteristics and social medical risk factors of households at risk in Amsterdam. Scand. J. Public Health 2009, 37, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/245/60/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Fischel, W.A. An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for its Exclusionary Effects. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, C. The racial origins of zoning in American cities. In Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows; Manning Thomas, J., Ritzdorf, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, D.M.P. Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America; Illustrated edition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, J.; Massey, D.S. The Effect of Density Zoning on Racial Segregation in U.S. Urban Areas. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J. Detroit: The Evolution of a Housing Crisis. 2019. Available online: https://mlpp.org/detroit-the-evolution-of-a-housing-crisis/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Carr, J.H. The Complexity of Segregation: Why it Continues 30 Years After the Enactment of the Fair Housing Act. Cityscape 1999, 4, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, R. The Color of Law; Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Fair Housing Alliance. Unequal Opportunity—Perpetuating housing segregation in America (p. 30). National Fair Housing Alliance. 2006. Available online: https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/trends2006.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD Charges Facebook with Housing Discrimination over Company’s Targeted Advertising Practices. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/HUD_No_19_035 (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Booker, B. Housing Department Slaps Facebook With Discrimination Charge. National Public Radio (NPR). 2019. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/03/28/707614254/hud-slaps-facebook-with-housing-discrimination-charge (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Khatry, S. Facebook and Pandora’s box: How using Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in advertising resulted in housing discrimination. Appl. Mark. Anal. 2020, 6, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- National Fair Housing Alliance. 2017 Fair Housing Trends Report. 2017. Available online: http://nationalfairhousing.org/2017-fair-housing-trends-report/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Beard, J.R.; Blaney, S.; Cerda, M.; Frye, V.; Lovasi, G.S.; Ompad, D.; Rundle, A.; Vlahov, D. Neighborhood characteristics and disability in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2009, 64, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, N.; Nitka, D.; Gariepy, G.; Malla, A.; Wang, J.; Boyer, R.; Messier, L.; Strychar, I.; Lesage, A. Association between neighborhood-level deprivation and disability in a community sample of people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); U.S. Department of Justice. Joint Statement of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Justice Reasonable Accommodations under the Fair Housing Act. 2004. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2010/12/14/joint_statement_ra.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

| DMA Mean (SE) | Macomb Mean (SE) | Oakland Mean (SE) | Wayne Mean (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| % of women | 51.69% (0.12) | 51.42% (0.23) | 51.5% (0.18) | 51.88% (0.18) |

| % of adults aged 18–64 years | 62.84% (0.16) | 62.88% (0.27) | 63.22% (0.33) | 62.61% (0.23) |

| % with high school education or more | 86.9% (0.29) | 88.4% (0.36) | 93.10% (0.30) | 82.9% (0.45) |

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||

| % of Non-Hispanic White | 61.5% (1.04) | 82.37% (0.96) | 75.90% (1.27) | 46.0% (1.57) |

| Median household income (per 100 k) | 50.06 (0.69) | 51.87 (1.08) | 67.88 (1.40) | 40.11 (0.80) |

| % of owner-occupied households | 67.17% (0.63) | 74.0% (1.13) | 73.4% (1.20) | 61.30% (0.86) |

| Housing discrimination outcomes | ||||

| Total number of housing discrimination incidents | 988 | 143 | 304 | 541 |

| Percentage of total incidents attributed to race | 54.25% | 54.55% | 58.88% | 51.57% |

| Percentage of total incidents attributed to disability | 40.89% | 43.36% | 39.14% | 41.22% |

| Percent of total incidence that occurred during rental transactions | 66.40% | 62.94% | 69.08% | 65.80% |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | |

| % of NHW | 0.98 *** | 0.98, 0.99 | - | - | - | - |

| Median Household Income (per 100 k) | - | - | 0.97 *** | 0.96, 0.97 | - | - |

| % homeownership | - | - | - | - | 0.96 *** | 0.97, 0.98 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | |

| % of NHW | 0.99 *** | 0.98, 0.99 | 0.99 *** | 0.98, 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 |

| Median Household Income (per 100 k) | 0.99 ** | 0.98, 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.96 *** | 0.96, 0.97 |

| % homeownership | 0.97 *** | 0.97, 0.98 | 0.97 *** | 0.96, 0.98 | 0.96 *** | 0.95, 0.96 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehdipanah, R.; Bess, K.; Tomkowiak, S.; Richardson, A.; Stokes, C.; White Perkins, D.; Cleage, S.; Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J. Residential Racial and Socioeconomic Segregation as Predictors of Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410429

Mehdipanah R, Bess K, Tomkowiak S, Richardson A, Stokes C, White Perkins D, Cleage S, Israel BA, Schulz AJ. Residential Racial and Socioeconomic Segregation as Predictors of Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410429

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehdipanah, Roshanak, Kiana Bess, Steve Tomkowiak, Audrey Richardson, Carmen Stokes, Denise White Perkins, Suzanne Cleage, Barbara A. Israel, and Amy J. Schulz. 2020. "Residential Racial and Socioeconomic Segregation as Predictors of Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410429

APA StyleMehdipanah, R., Bess, K., Tomkowiak, S., Richardson, A., Stokes, C., White Perkins, D., Cleage, S., Israel, B. A., & Schulz, A. J. (2020). Residential Racial and Socioeconomic Segregation as Predictors of Housing Discrimination in Detroit Metropolitan Area. Sustainability, 12(24), 10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410429