A Materials Bank for Circular Leuven: How to Monitor ‘Messy’ Circular City Transition Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

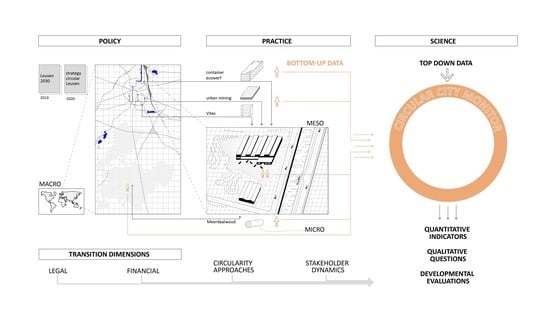

1.1. Science: What Is A Circular City and How to Monitor Progress and Impacts?

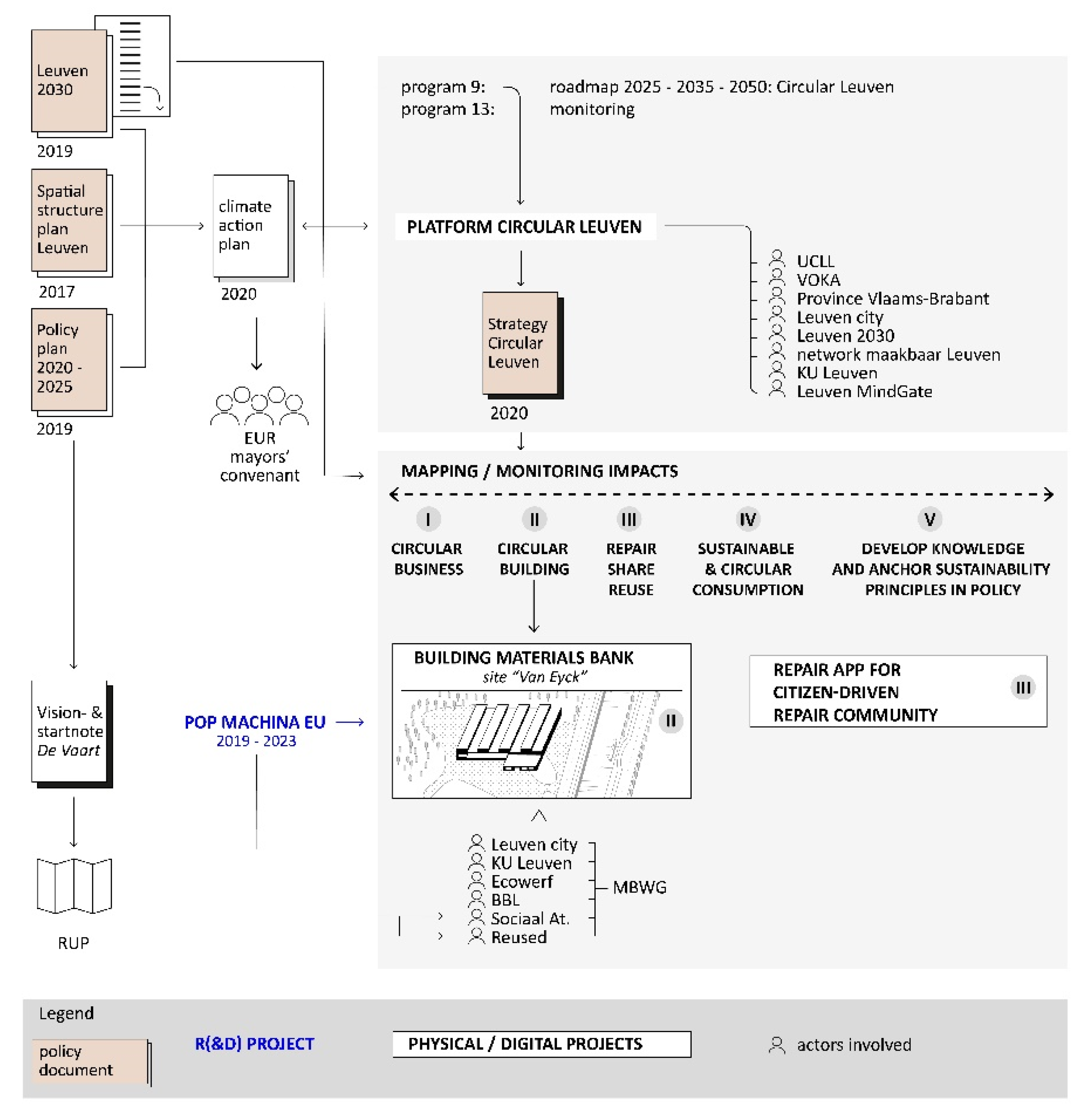

1.2. Policy: Transitioning Leuven to A Circular City

1.3. Practice: Realizing A Building Materials Bank Contributing to A Circular City

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participatory Action Research

2.2. Author Backgrounds and Research Entry Points

3. Results

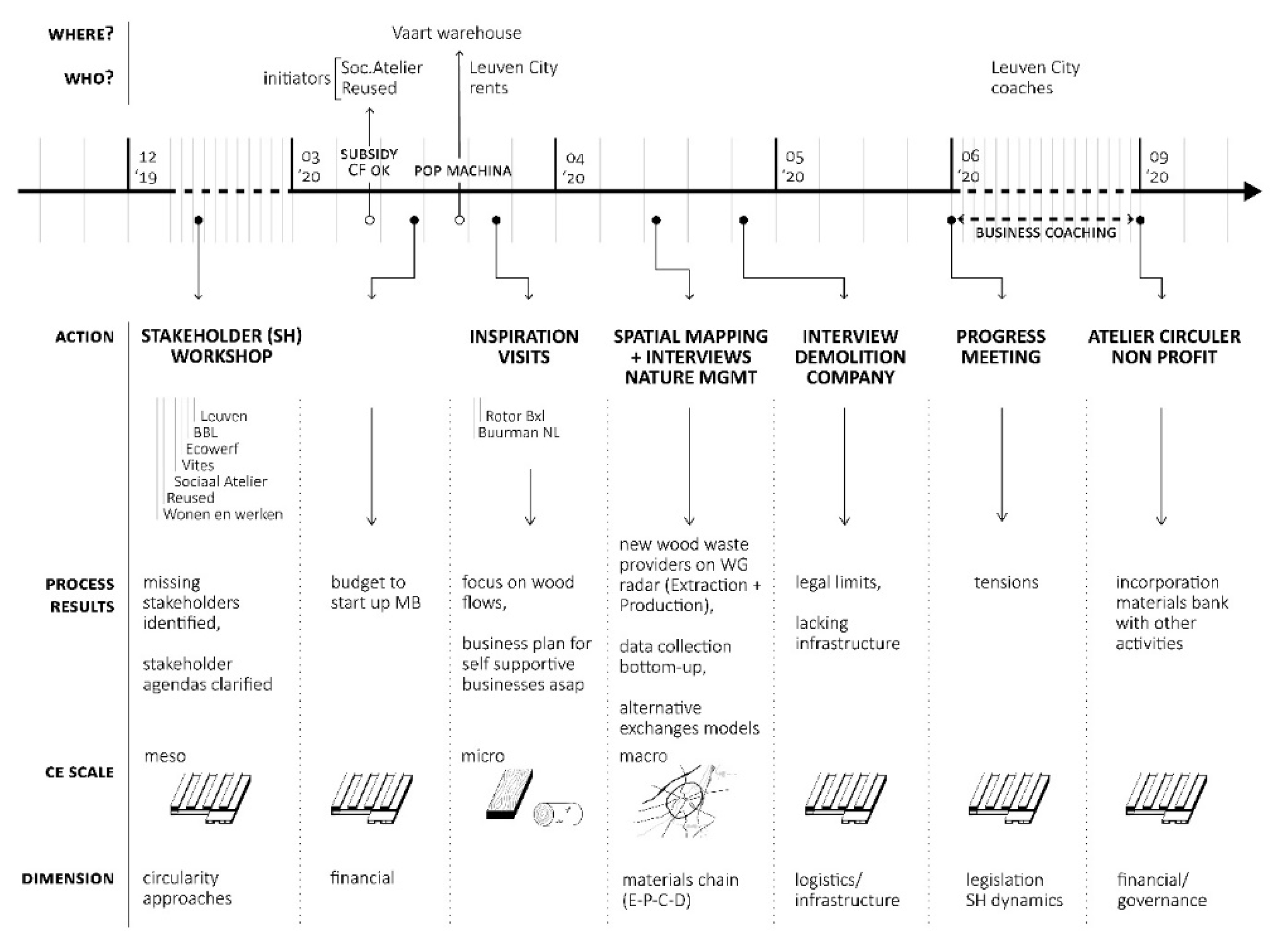

3.1. The Materials Bank’s Messy Development Process

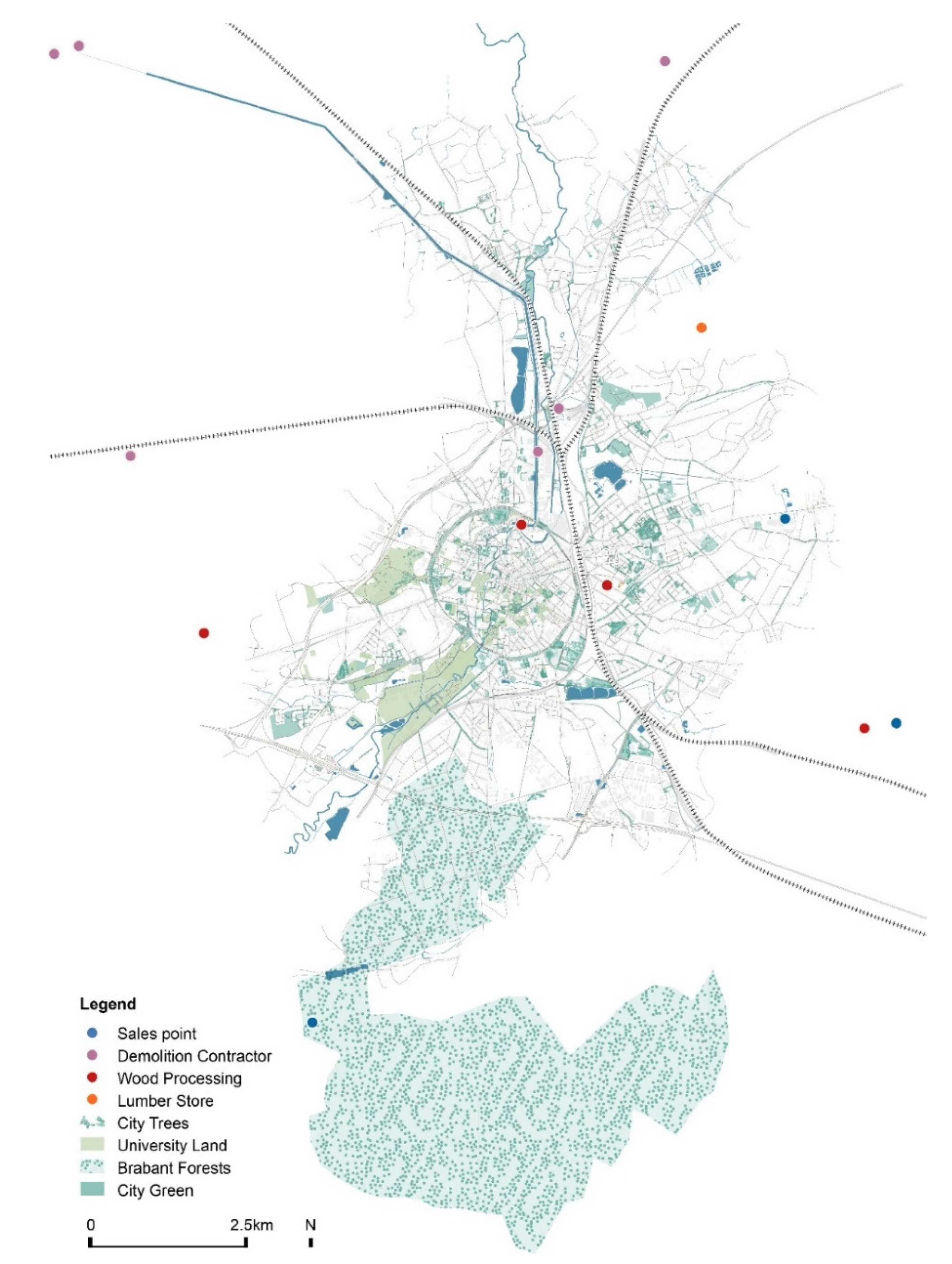

- Micro: wood waste

- Meso: materials bank

- Macro: hinterlands and wood ecosystem (logistical chains, sheds, externalities)

- Spatial dimensions:

- Infrastructural networks and logistics:

- Stakeholder network and dynamics:

- Circularity approaches:

- Financial structure:

- Legal aspects (Policy)

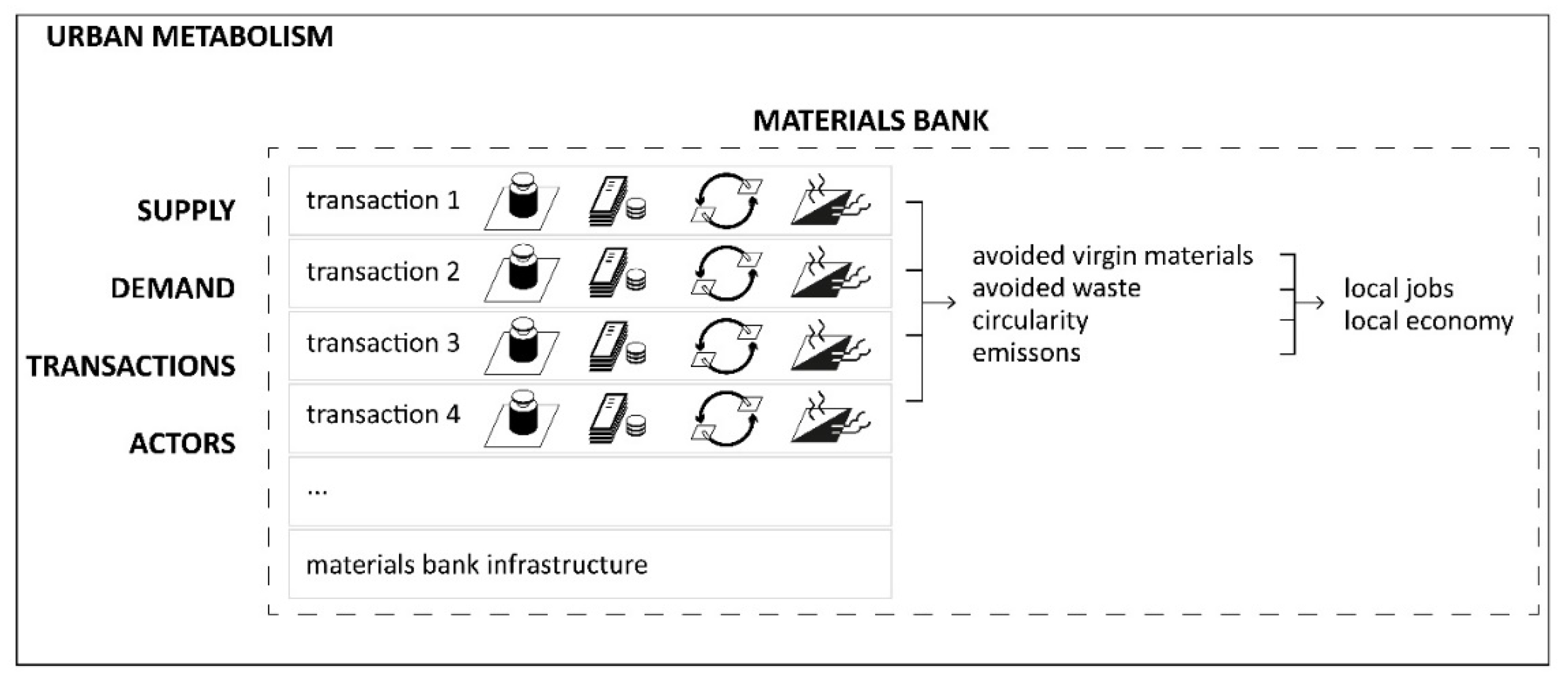

3.2. How to Monitor the Performance of A Materials Banks, and How to Link This Performance to A City-Wide CE Monitoring?

- ▪

- What would the materials bank mean for the people of the city to thrive? The materials bank can provide local production and local employment (including the social economy), with the potential to contribute to an inclusive and resilient city where different actors are in fact helping each other by exchanging material flows.

- ▪

- What would the materials bank mean for the city to thrive within its natural habitat? The materials bank can become a component in realizing local and sustainable wood flows, while contributing to the reinforcement of natural infrastructures and habitats.

- ▪

- What would the materials bank mean for the city to respect the wellbeing of people worldwide? In a global context, the activities of the materials bank could contribute to fairer consumption by excluding exploitation of people in any part of the wood supply chain. While this may seem a long shot, compare for instance alternative labor and societal conditions in wood harvesting in distant countries.

- ▪

- What would it mean for the city to respect the health of the whole planet? The materials bank could be seen to contribute to decreasing deforestation in distant regions by using locally obtained inputs, as such helping to balance natural cycles worldwide, thereby enabling nature to regenerate from any wood flow impact.

4. Discussion

4.1. Bottom-Up Data Gathering

4.2. Monitoring Broader and Indirect Effects

4.3. Developmental Evaluation of the Transition Process

4.4. Clarifying and Resolving Legal Bottlenecks

4.5. Lessons Drawn for the Management of the Materials Bank

- -

- Organize bottom-up data collection for circular city monitoring from the very start

- -

- Set up an organizational system to facilitate contact and data exchange between stakeholders. e.g., an open source map geographically locating stakeholders in the material flow ecosystem, including relevant information on their potential roles in circular flows.

- -

- Acknowledge and take into account the difficult path to defining new roles and engagements with all stakeholders and to achieve collaboration in an atmosphere of trust and transparency with clear expectations and hesitations.

- -

- Define the role of the local government as flexibly as possible: from a facilitator and supporter to an intensive business coach and data harvester, simultaneously capturing bottlenecks in other forms of legislation.

- -

- Pay attention to the different circular economy approaches and to what extent they contribute to an environmentally and socially just city.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- City of Amsterdam. Amsterdam Circular Strategy 2020–2025; City of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.amsterdam.nl/en/policy/sustainability/circular-economy/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Paris City Council. Paris Circular Economy Plan. 2017. Available online: https://www.paris.fr/pages/economie-circulaire-2756 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Government of the Brussels-Capital Region. Brussels Regional Program for a Circular Economy 2016–2020 (BRPCE). 2016. Available online: https://www.circulareconomy.brussels/a-propos/le-prec/?lang=en#:~:text=On%2010%20March%202016%2C%20the,million%20for%20the%20year%202016.&text=To%20transform%20environmental%20objectives%20into%20economic%20opportunities (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- London Waste and Recycling Board. London’s Circular Economy Route Map. 2017. Available online: https://www.lwarb.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/LWARB-London%E2%80%99s-CE-route-map_16.6.17a_singlepages_sml.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Glasgow Chamber of Commerce, Zero Waste Scotland, Glasgow City Council and Circle Economy Circular Glasgow: A Vision and Action Plan for the City of Glasgow. 2016. Available online: https://circularglasgow.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Glasgow-City-Scan.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- UNEP. Brussels Capital Region: Circular Economy Transition. 2018, p. 32. Available online: https://www.circulareconomy.brussels/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GIREC_Brussels-report_Final.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- World Bank. Urban Development Overview. 2017. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A.; Birkie, S.E. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Olivetti, E.A.; Cullen, J.M.; Potting, J.; Lifset, R. Taking the Circularity to the Next Level: A Special Issue on the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiho, S.; Mäki, E.; Wessberg, N.; Paavola, M.; Tuominen, P.; Antikainen, M.; Heikkilä, J.; Rozado, C.A.; Jung, N. Towards circular cities—Conceptualizing core aspects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; De Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; Rousseau, S.; De Jaeger, S.; Moraga, G.; Dewulf, J.; De Meester, S.; Van Passel, S.; Compernolle, T.; Bachus, K.; et al. Towards a more direct policy feedback in circular economy monitoring via a societal needs perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Random House Business Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsperger, C.; Bourg, D. Vers une économie authentiquement circulaire. Revue de l’OFCE 2016, 145, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, H. The Gaia Atlas of Cities: New Directions for Sustainable Living; Gaia Books Limited: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. 2013, Volume 1. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-1-an-economic-and-business-rationale-for-an-accelerated-transition (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Marin, J.; De Meulder, B. Interpreting circularity. Circular City Representations Revealing Transition Drivers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, A.; Gaspari, J.; Gianfrate, V.; Longo, D.; Boulanger, S.O. Circular city: A methodological approach for sustainable districts and communities. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2019, 183, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Fanning, A.L.; Krestyaninova, O.; Raworth, K.; Dwyer, J.; Hagerman Miller, N.; Eriksson, F. Creating City Portraits. A Methodological Guide from the Thriving Cities Initiative. 2020, p. 44. Available online: https://doughnuteconomics.org/Creating-City-Portraits-Methodology.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Angrisano, M.; Girard, L.F. Circular Economy Strategies in Eight Historic Port Cities: Criteria and Indicators Towards a Circular City Assessment Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, A.; De Schoenmakere, M.; Gillabel, J.; Martin, J.; Hoogeveen, Y. Circular Economy in Europe. Developing the knowledge base. Agency Rep. 2016, 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain; PBL Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Potting, J.E.; Hanemaaijer, H.; Delahaye, R.; Hoekstra, R.; Ganzevles, J.; Lijzen, J. Circular Economy: What We Want to Know and Can Measure; Publication Number 3217; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; Available online: https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2018-circular-economy-what-we-want-to-know-and-can-measure-3217.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J. A Developmental Evaluation Primer. 2008, p. 69. Available online: https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/A-Developmental-Evaluation-Primer-EN.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Vandenbroeck, P. Het Herpositioneren en Verder Versterken van de Visie (Vorming) van Plan C—Vlaams Transitienetwerk Duurzaam Materialenbeheer. 2013, p. 114. Available online: https://issuu.com/vlaanderen-be/docs/5793ae2a-35dd-4615-905a-8fc2e195a5f4 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Ecorys. Indicators for Circular Economy (CE) Transition in Cities—Issues and Mapping Paper (Version 4). 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/urban_agenda_partnership_on_circular_economy_-_indicators_for_ce_transition_-_issupaper_0.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Wilts, H.; Steger, S. CIRCTER—Circular Economy and Territorial Consequences Applied Research Final Report Annex 10 Measuring Rban Circularity Based on a Territorial Perspective Version 10/10/2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/CIRCTER%20FR%20Annex%2010%20Measuring%20urban%20circularity_0.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- De Ferreira, A.C.; Nerini, F.F. A Framework for Implementing and Tracking Circular Economy in Cities: The Case of Porto. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaerts, L.; Chapman, D.; Eyckmans, J.; Van Acker, K. Circular Economy Indicators for Person Mobility and Transport. 2020. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/3151407?limo=0 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- City of Amsterdam. Amsterdam Circular Monitor. 2020, p. 63. Available online: https://www.amsterdam.nl/bestuur-organisatie/volg-beleid/coalitieakkoord-uitvoeringsagenda/gezonde-duurzame-stad/amsterdam-circulair-2020-2025/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Christis, M.; Athanassiadis, A.; Vercalsteren, A. Implementation at a city level of circular economy strategies and climate change mitigation—The case of Brussels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadis, A.; Christis, M.; Bouillard, P.; Vercalsteren, A.; Crawford, R.H.; Khan, A.Z. Comparing a territorial-based and a consumption-based approach to assess the local and global environmental performance of cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.; Pauwels, H.; Van Couwenberghe, J. Leuven Circulair. 2020. Available online: https://roadmap.leuven2030.be/pdf/L2030_Roadmap_Programma9.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competetive Europe. Study Commissioned by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthurFoundation_Growth-Within_July15.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Achterberg, E.; Hinfelaar, J.; Bocken, N. Master Circular Business with the Value Hil. 2016. Available online: https://publish.circle-economy.com/financing-circular-business (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Kenis, A.; Lievens, M. Imagining the carbon neutral city: The (post)politics of time and space. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 49, 1762–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop-Machina. Available online: https://pop-machina.eu/ (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Stad Leuven. Bestuursnota 2019–2025. 2019. Available online: https://www.leuven.be/sites/leuven.be/files/documents/2019-10/baanbrekend_leuven_-_bestuursnota_2019-2025.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Freire, P. Pedagogie van de Onderdrukten (Translation of The Pedagogy of the Oppressed); De Toorn: Baarn, The Netherlands, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff, J.; Whitehead, J. All You Need to Know about Action Research; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Navare, K.; Muys, B.; Vrancken, K.C.; Van Acker, K. Circular economy monitoring—How to make it apt for biological cycles? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, W. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Van Couwenberghe, J. Pop-Machina Verslag Workshop ‘Naar een Materialenbank in Leuven’ 2 December 2019; 2019; p. 15, Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Doménech, T.; Davies, M. The role of Embeddedness in Industrial Symbiosis Networks: Phases in the Evolution of Industrial Symbiosis Networks. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2010, 20, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UrbanWINS Toolkit. Available online: https://www.urbanwins.eu/toolkit/ (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- SCREEN-lab. Assessment Criteria for Circular Economy Projects; Rev 4.0- March 2019. 2019. Available online: http://www.screen-lab.eu/deliverables/Table-rev4.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Taelman, S.; Sanjuan-Delmás, D.; Tonini, D.; Dewulf, J. An operational framework for sustainability assessment including local to global impacts: Focus on waste management systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 104964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Eyckmans, J.; Van Acker, K. Does Car-Sharing Reduce Car-Use? An Impact Evaluation of Car-Sharing in Flanders, Belgium. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadis, A. Urban metabolism in policy and practice. In Urban Metabolism in Policy and Practice; Perspective.Brussels: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kasperson, R. Barriers in the science-policy-practice interface: Toward a knowledge-action-system in global environmental change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotti, D. Evaluating urban metabolism assessment methods and knowledge transfer between scientists and practitioners: A combined framework for supporting practice-relevant research. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1458–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, L.; Dehaene, M.; Goethals, M.; Kuhk, A.; Schreurs, J. Living labs. Co-Evolutie Planning Met Onderzoekers, Overheden, Burgers en Ondernemers Voor Uitvoerbare Ruimtelijke Projecten 2015. Available online: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/7022845/file/7022846.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

| Activities Conducted by the UDR in Relation to the Materials Bank Core Working Group | |

|---|---|

| December 2019 | Facilitating a one-hour stakeholders conversation on which role(s) they envision for themselves within the materials bank project as well as how they would see it being materialized. Collecting relevant stakeholder information (relevant locations, partners, and infrastructures) using a map of Leuven with the stakeholders. |

| April 2020 | Assisting in a virtual site visit of reference project Buurman in Rotterdam. |

| May 2020 | Spatial mapping complemented with phone interviews to understand Leuven’s wood metabolism throughout the entire chain of extraction, processing, consumption, and disposal to gain insights into different wood types, sizes, and possible applications and potential collaborations. |

| October 2019–June 2020 | Assisting in MBWG meetings and bi-lateral brainstorms with the city project leader. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marin, J.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K. A Materials Bank for Circular Leuven: How to Monitor ‘Messy’ Circular City Transition Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410351

Marin J, Alaerts L, Van Acker K. A Materials Bank for Circular Leuven: How to Monitor ‘Messy’ Circular City Transition Projects. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410351

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarin, Julie, Luc Alaerts, and Karel Van Acker. 2020. "A Materials Bank for Circular Leuven: How to Monitor ‘Messy’ Circular City Transition Projects" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410351

APA StyleMarin, J., Alaerts, L., & Van Acker, K. (2020). A Materials Bank for Circular Leuven: How to Monitor ‘Messy’ Circular City Transition Projects. Sustainability, 12(24), 10351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410351