Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Crow and the Raven

2.1. Intelligent Like a Crow and Raven

2.2. Ravens and Crows in Myths and Beliefs

2.3. Scavengers

2.4. The Crow and Raven in Popular Culture

3. Birds in the City

3.1. Ecosystem Services Provided by Birds

3.2. Ravens and Crows in the City

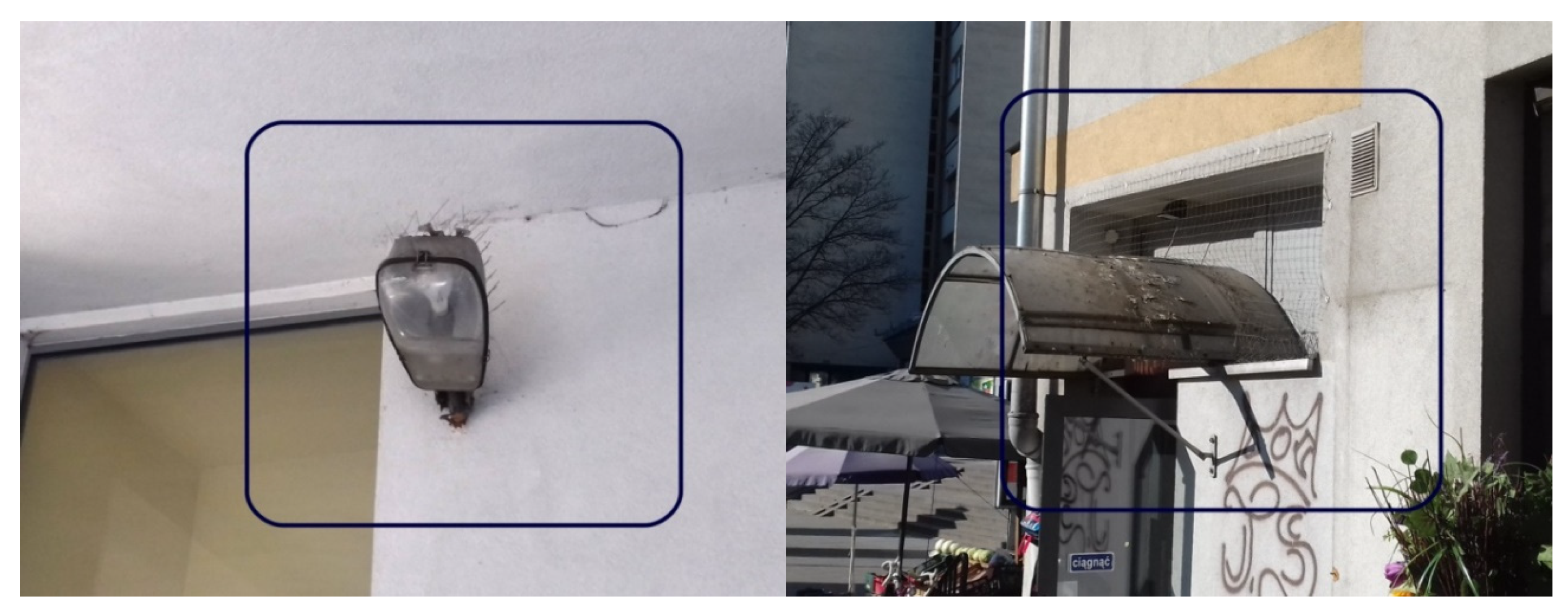

3.3. Safeguards against Bird-Induced Losses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Respondents

4.2. Surveys

4.3. Result Presentation

5. Results

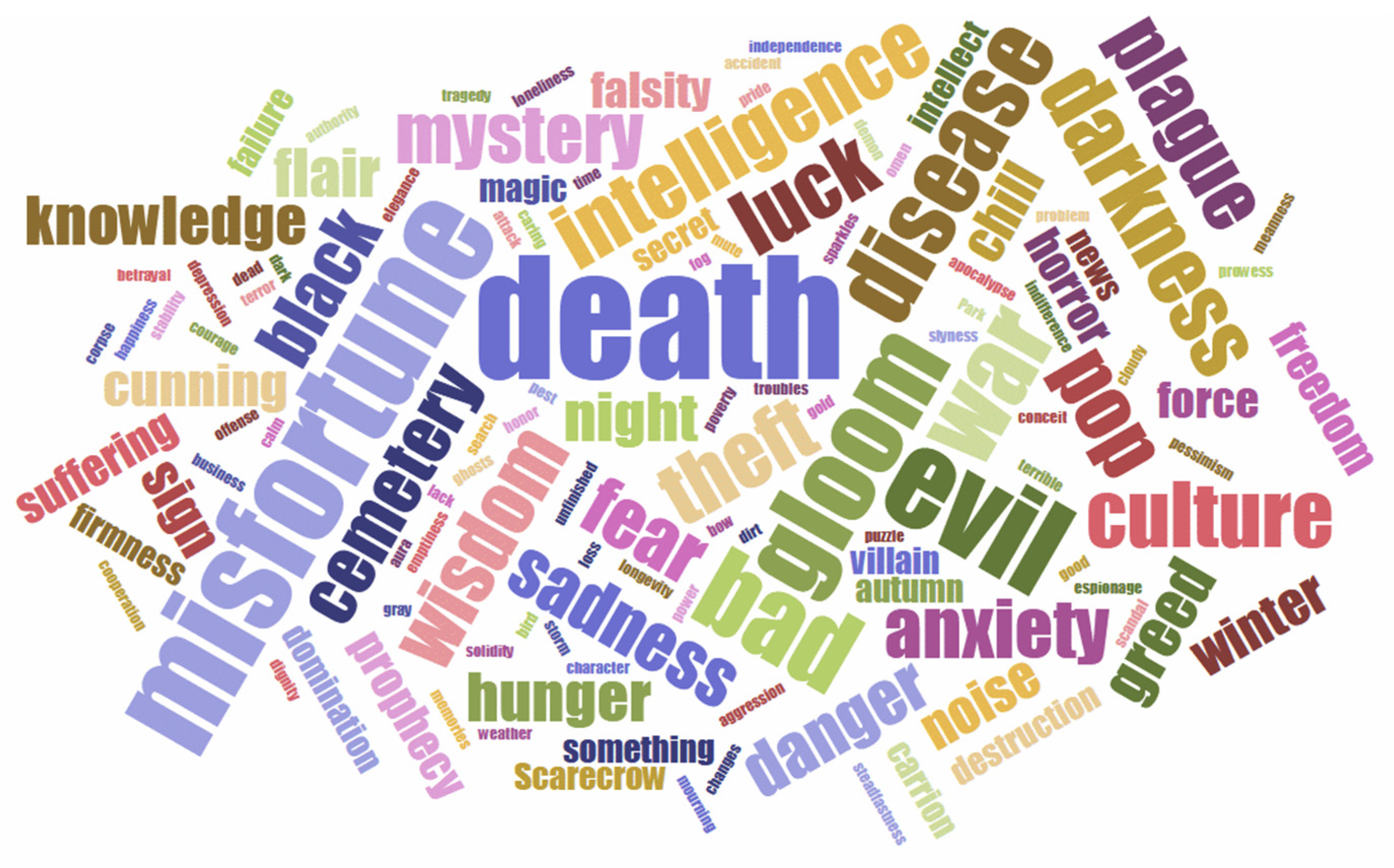

5.1. The Symbolism of the Crow and Raven

5.2. Legends with Crows and Ravens

5.3. Crows and Ravens in the Lives of City Dwellers

5.4. The Crow and Raven in Popular Culture

5.5. In-Depth Interviews

6. Discussion

Discussion on Research Questions and Hypothesis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marzluff, J.M.; Angell, T. In the Company of Crows and Ravens; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anjos, L. Family Corvidae (Crows). In Handbook of the Birds of the World. Bush-Shrikes to Old Sparrows; Hoyo, J., Elliot, A., Christie, D.A., Eds.; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; Volume 14, pp. 494–640. [Google Scholar]

- Jønsson, K.A.; Fabre, P.-H.; Irestedt, M. Brains, tools, innovation and biogeography in crows and ravens. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.; Duncan, R.P.; Blackburn, T.M.; Cassey, P.; Lefebvre, L. Big brains, enhanced cognition, and response of birds to novel environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5460–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serjeantson, D.; Morris, J. Ravens and crows in iron age and roman britain. Oxf. J. Archaeol. 2011, 30, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihei, Y.; Higuchi, H. When and where did crows learn to use automobiles as nutcrackers? Tohoku Psychol. Folia 2001, 60, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff, J.M.; Angell, T. Cultural Coevolution: How the Human Bond with Crows and Ravens Extends Theory and Raises New Questions. J. Ecol. Anthr. 2005, 9, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wascher, C.A.F.; Bugnyar, T. Behavioral Responses to Inequity in Reward Distribution and Working Effort in Crows and Ravens. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.; Timmermans, S.; Lefebvre, L. Behavioural flexibility and invasion success in birds. Anim. Behav. 2002, 63, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, D. The Raven: A Natural History in Britain and Ireland; Poyser: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmore, S.B. Crows, Jays, Ravens and Their Relatives; David & Charles: Newton Abbot, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bugnyar, T.; Kotrschal, K. Leading a conspecific away from food in ravens (Corvus corax)? Anim. Cogn. 2004, 7, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition; Routledge: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhouse-Green, M.J.; Aldhouse-Green, S. The Quest for the Shaman: Shape-Shifters, Sorcerers, and Spirit-Healers of Ancient Europe; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.J. Animals in Celtic Life and Myth; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Honegger, T. Form and function: The beasts of battle revisited. Engl. Stud. 1998, 79, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowick, K.E. Truth and Symbolism: Mythological Perspectives of the Wolf and Crow; Boston College: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Biegeleisen, H. Śmierć w Obrzędach, Zwyczajach i Wierzeniach Ludu Polskiego [Death in the Rituals, Customs and Beliefs of the Polish People]; Dom Książki Polskiej S-ka Akc.: Warszawa, Poland, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, F.V. Red as blood, white as snow, black as crow: Chromatic symbolism of womanhood in fairy tales. Marvels Tales J. Fairy-Tale Stud. 2007, 21, 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Żeromski, S. Rozdzióbią Nas Kruki, Wrony [Ravens and Crows Will Peck Us to Pieces]; Nakładem Księgarni L. Zwolińskiego i Spółki: Kraków, Poland, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, I.; Tagliacozzo, A. I resti ossei animali dal santuario preromano in localitá“Fornace” di Altino (VE). In Culti e Santuari antichi in Altino e nel Veneto Orientale (Altinum, Studi e Ricerche Sulla Gallia Cisalpina 14, Studi di Archeologia, Epigrafia e Storia 2); del Sacro, G., Ed.; Quasar Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2001; Volume 14, pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, J.T.; Vries, L.S. De Raaf in de Waterput. Archeozoölogisch Onderzoek van de Romeinse Stad Forum Hadriani (120–270 AD), Gem. Leidschendam-Voorburg (LVB-FO 9888); ArchaeoBone Rapport Nr: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, P.; Woodward, A. Dedicating the town: Urban foundation deposits in Roman Britain. World Archaeol. 2004, 36, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liker, A.; Papp, Z.; Bókony, V.; Lendvai, Á.Z. Lean birds in the city: Body size and condition of house sparrows along the urbanization gradient. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedlicka, J.A.; Greenberg, R.; Letourneau, D.K. Avian Conservation Practices Strengthen Ecosystem Services in California Vineyards. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenny, D.G.; DeVault, T.L.; Johnson, M.D.; Kelly, D.; Sekercioglu, C.H.; Tomback, D.F.; Whelan, C.J. The Need to Quantify Ecosystem Services Provided by Birds. Auk 2011, 128, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheński, M.; Ciebiera, O.; Dolata, P.T.; Jerzak, L.; Zbyryt, A. Ochrona Ptaków w Mieście [Protection of Birds in the City]; RDOŚ w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim: Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hubacek, K.; Kronenberg, J. Synthesizing different perspectives on the value of urban ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J.; Bocheński, M.; Dolata, P.T.; Jerzak, L.; Profus, P.; Tobółka, M.; Tryjanowski, P.; Wuczyński, A.; Żołnierowicz, K.M. Znaczenie bociana białego Ciconia ciconia dla społeczeństwa: Analiza z perspektywy koncepcji usług ekosystemów. Chrońmy Przyr. Ojcz. 2013, 69, 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrost, P. The fauna of ancient Poland in the light of archaeozoological research. In Skeletons in her Cupboard, Oxbow Monograph; Clason, A., Payne, S., Uerpmann, H.P., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 1993; Volume 34, pp. 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Haag-Wackernagel, D.; Geigenfeind, I. Protecting buildings against feral pigeons. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmhurst, K.S.; Grady, K. Fauna Protection in a Sustainable University Campus: Bird-Window Collision Mitigation Strategies at Temple University. In Handbook of Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Brandli, L., Castro, P., Newman, J., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Król, K.; Kao, R.; Hernik, J. The Scarecrow as an Indicator of Changes in the Cultural Heritage of Rural Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klem, D.; Farmer, C.J.; Delacretaz, N.; Gelb, Y.; Saenger, P.G. Architectural and Landscape Risk Factors Associated with Bird–glass Collisions in an Urban Environment. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2009, 121, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E.; Depner, F. Testing for measurement equivalence of human values across online and paper-and-pencil surveys. Qual. Quant. 2009, 45, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, M.; Solmaz, B. The Changing Face of the Employees–Generation Z and Their Perceptions of Work (A Study Applied to University Students). Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, R.; Dries, N. Attracting Generation Y: How Work Values Predict Organizational Attraction in Graduating Students in Belgium. In Managing the New Workforce: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation; Ng, E.S., Lyons, S., Schweitzer, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S.M.; Haytko, D.L.; Phillips, J. What drives college-age Generation Y consumers? J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.K.; Sadaghiani, K. Millennials in the Workplace: A Communication Perspective on Millennials’ Organizational Relationships and Performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkup, S.B. Working with Generations X and Y In Generation Z Period: Management Of Different Generations In Business Life. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardey, M. Generation C: Content, Creation, Connections and Choice. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 53, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levickaite, R. Y, X, Z Kartos: Pasaulio be sienų idėjos formavimas naudojantis socialiniais tinklais (lietuvos atvejis). Creat. Stud. 2010, 3, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąckiewicz, E. Pokolenie 60+ a pokolenie Z na rynku nowoczesnych usług bankowych. Zarządzanie Finanse 2018, 16, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- LaRose, R.; Tsai, H.-Y.S. Completion rates and non-response error in online surveys: Comparing sweepstakes and pre-paid cash incentives in studies of online behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R.; San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J.L. Improvement Actions for a More Social and Sustainable Public Procurement: A Delphi Analysis. Sustainablity. 2019, 11, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisika, S.N.; Park, J.; Yeom, C. The Impact of Legislation on Sustainability of Farm Forests in Kenya: The Case of Lugari Sub-County in Kakamega County, Kenya. Sustainability 2019, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, M.; Villarroya, A.; Borrego, Á.; Ollé, C. Response Rates and Data Quality in Web and Mail Surveys Administered to PhD Holders. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2010, 29, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, C.F.; Arroyo, B.; Amar, A. A review of the impacts of corvids on bird productivity and abundance. Ibis 2014, 157, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonier, F. Hormones in the city: Endocrine ecology of urban birds. Horm. Behav. 2012, 61, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M. Worldwide Urbanization and Its Effects on Birds. In Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Marzluff, J.M., Bowman, R., Donnelly, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Slabbekoorn, H. Songs of the city: Noise-dependent spectral plasticity in the acoustic phenotype of urban birds. Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.A.; Chadwick, M.A. What makes a species synurbic? Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmihorski, M.; Halba, R.; Mazgajski, T.D. Long-term spatio-temporal dynamics of corvids wintering in urban parks of Warsaw, Poland. Ornis Fennica 2010, 87, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization, Biodiversity, and ConservationThe impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. Bioscience 2002, 52, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, R.; Annett, C. The Ecology of Western Gulls in Habitats Varying in Degree of Urban Influence. In Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Marzluff, J.M., Bowman, R., Donnelly, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Mennechez, G.; Clergeau, P. Effect of urbanization on habitat generalists: Starlings not so flexible? Acta Oecol. 2006, 30, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochat, E. Credit or Debit? Resource Input Changes Population Dynamics of City-Slicker Birds. Oikos 2004, 106, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clucas, B.; Marzluff, J.M.; Kübler, S.; Meffert, P. New Directions in Urban Avian Ecology: Reciprocal Connections between Birds and Humans in Cities. In Perspectives in Urban Ecology: Ecosystems and Interactions between Humans and Nature in the Metropolis of Berlin; Endlicher, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Clucas, B.; Rabotyagov, S.; Marzluff, J.M. How much is that birdie in my backyard? A cross-continental economic valuation of native urban songbirds. Urban Ecosyst. 2014, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Attitudes, Knowledge, and Behavior Toward Wildlife Among the Industrial Superpowers: United States, Japan, and Germany. J. Soc. Issues 1993, 49, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clucas, B.; Marzluff, J.M. Attitudes and actions toward birds in urban areas: Human cultural differences influence bird behavior. Auk 2012, 129, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generation | Seniors | Generation Y | Generation Z | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Born 1940–1960 | Born 1980–1999 | Born 2000–2002 | |

| Number respondents | 13 | 235 | 177 | 425 |

| Percentage (%) | 3.1 | 55.3 | 41.6 | 100 |

| Age | Urban | Rural | Suburbs, Outskirts | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number respondents | 222 | 155 | 48 | 425 |

| Percentage (%) | 52.2 | 36.5 | 11.3 | 100 |

| Keyword | pestilence | disease | darkness | war | death | cemetery | misfortune | evil |

| Frequency * | 9 | 17 | 12 | 18 | 122 | 12 | 59 | 39 |

| Keyword | intellect/intelligence | freedom | wisdom | courage | strength | reliability | cunning | valor |

| Frequency * | 12 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Król, K.; Hernik, J. Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410231

Król K, Hernik J. Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410231

Chicago/Turabian StyleKról, Karol, and Józef Hernik. 2020. "Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410231

APA StyleKról, K., & Hernik, J. (2020). Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas. Sustainability, 12(24), 10231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410231