Relationships among Ethical Commitment, Ethical Climate, Sustainable Procurement Practices, and SME Performance: An PLS-SEM Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Association between Ethical Commitment of Top Management and Ethical Climate

2.2. Association between Ethical Commitment of Top Management and Sustainable Procurement Practices

2.3. Association between Ethical Climate and Sustainable Procurement Practices

2.4. Association between Sustainable Procurement Practices and Company Performance

2.5. Association between Ethics of Top Management’s Commitment and Company Performance

2.6. Association between Ethical Climate and Company Performance

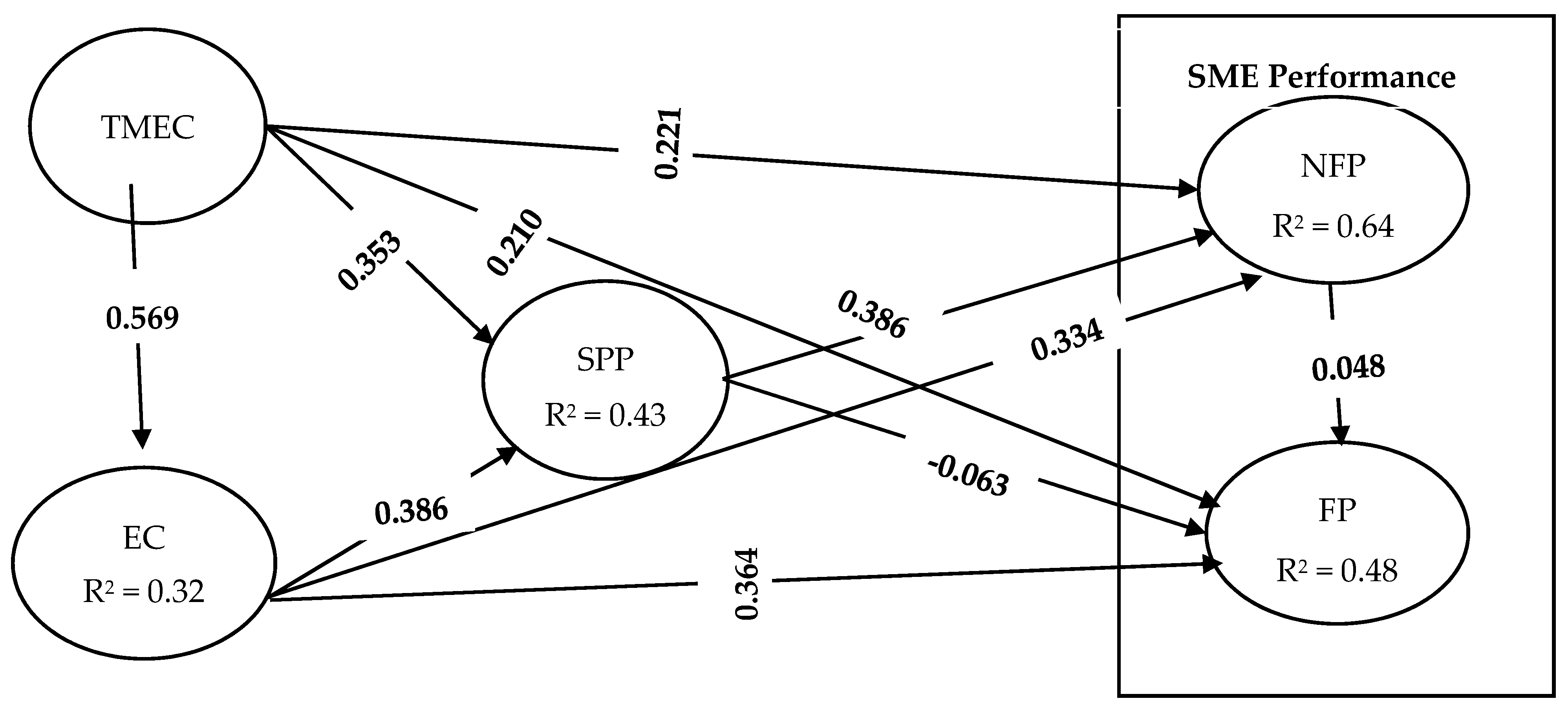

2.7. Theoretical Framework

3. Model and Analysis

3.1. Measurement of Constructs and Psychometric Properties

Psychometric Properties

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4. Evaluation of Structural Model

3.5. Test for Mediation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Implications and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, H.; Preuss, L. Fostering sustainability through sourcing from small businesses: Public sector perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Dangayach, G.; Singh, A.; Meena, M.; Rao, P. Implementation of sustainable manufacturing practices in Indian manufacturing companies. Bench. Int. J. 2018, 25, 2441–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Chakrabarty, A. World-class sustainable manufacturing: Framework and a performance measurement system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5207–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lather, A.S. Measuring the Ethical Quotient of Corporations: The Case of Small and Medium Enterprises in India; The Forum on Public Policy: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 2002; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Scott, W.R. Introduction: Institutional theory and organizations. Inst. Const. Org. 1995, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, C.; Karri, R.; Vollmar, P. Principal theory and principle theory: Ethical governance from the follower’s perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnafous-Boucher, M.; Porcher, S. Towards a stakeholder society: Stakeholder theory vs theory of civil society. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbim, K.C. Effect of ethical leadership on corporate governance, performance and social responsibility: A study of selected deposit money banks in Benue state, Nigeria. Int. J. Comm. Dev. Manag. Stud. 2018, 2, 019–035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, S. The Role of Management in Establishing an Ethical Culture. 2016. Available online: https://www.ethicssage.com/2016/10/the-role-of-management-in-establishing-an-ethical-culture.html (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Mihelic, K.K.; Lipicnik, B.; Tekavcic, M. Ethical leadership. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M.J.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Roberts, J.A.; Chonko, L.B. The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psych. 2010, 95, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top management ethical leadership and firm performance: Mediating role of ethical and procedural justice climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.E.R. The Effects of Ethical Behavior on the Profitability of Firms: A Study of the Portuguese Construction Industry. Master Thesis, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization. In Bus. Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, L.J.; Painter-Morland, M. Introduction: Global perspectives on ethics in small and medium sized enterprises. In Ethics Small Medium Sized Enterp; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blome, C.; Paulraj, A. Ethical climate and purchasing social responsibility: A benevolence focus. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Banerjee, S. Ethical practices towards employees in small enterprises: A quantitative index. Int. J. Bus. Manage. Econ. Res. 2011, 2, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ononogbo, M.C.; Joel, A.; Edeja, S.M.E. Effect of ethical practices on the corporate image of SMEs in Nigeria: A survey of selected firms in Imo State. Int. J. Res. Bus. Manag. Account. 2016, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, R.M. The challenge of ethical leadership. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jureidini, M. Small and Medium Enterprises: Pulse of the Saudi Economy. 2017. Available online: http://english.alarabiya.net/en/business/economy/2017/09/18/Small-and-medium-enterprises-Pulse-ofthe-Saudi-economy.html (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- AlBar, A.M.; Hoque, M.R. Factors affecting the adoption of information and communication technology in small and medium enterprises: A perspective from rural Saudi Arabia. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 25, 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. A critique of conventional CSR theory: An SME perspective. J. Gen. Manag. 2004, 29, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z. Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises development in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 8, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Migdadi, M. Knowledge management enablers and outcomes in the small-and-medium sized enterprises. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, K.Y.; Osman, A.; Salahuddin, S.N.; Abdullah, S.; Lim, Y.J.; Sim, C.L. Relative advantage and competitive pressure towards implementation of e-commerce: Overview of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdah, W.O.A.; Sadi, M.A. Technology transfer in context with Saudi Arabian small-medium enterprises. Int. Manag. Rev. 2011, 7, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Palanski, M.E.; Walumbwa, F.O. When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Locander, W.B. Critical role of leadership on ethical climate and salesperson behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Admin. Scien. Quart. 1988, 33, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviňo, L.; Butterfield, K.; McCabe, D. The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behavior. Bus. Ethics Quart. 1998, 8, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, M. Functional top management team members: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos-Díez, J.-L.; Fernández-Gago, R.; Martínez-Campillo, A. How important are CEOs to CSR practices? An analysis of the mediating effect of the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Donaldson, L. Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.W.; Smith, D.B.; Grojean, M.W.; Ehrhart, M. An organizational climate regarding ethics: The outcome of leader values and the practices that reflect them. Lead. Quart. 2001, 12, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M. Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: The corporate ethical virtues model. J. Organ. Behav. E Int. J. Ind. Occup. Org. Psych. Behav. 2008, 29, 923–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. STRATEGIC Leadership: Top Executives and Their Effects on Organizations; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis, J.; Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Adenso-Diaz, B. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.; Brammer, S. The relationship between sustainable procurement and e-procurement in the public sector. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, A.; Lo, W. HSBC Sustainability—The What, the Why and the How. 2015. Available online: https://www.centennialcollege.hku.hk/f/upload/3370/HSBC_CSR_15_002C.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- DEFRA. Procuring the Future—The Sustainable Procurement Task Force National Action Plan; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2006. Available online: http://www.sustainabledevelopment.gov.uk/publications/procurementactionplan/documents/full-document (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green supply chain management in China: Pressures, practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V.; Maon, F.; Walker, H.; Brammer, S. Sustainable procurement in the United Kingdom public sector. Supp. Chain Manag. 2009, 14, 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Giunipero, L.C.; Hooker, R.E.; Denslow, D. Purchasing and supply management sustainability: Drivers and barriers. J. Purch. Supp. Manag. 2012, 18, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, A.J.; Islam, M.M.; Siwar, C.; Fien, J. Sustainable procurement in Malaysian organizations: Practices, barriers and opportunities. J. Purch. Supp. Manag. 2014, 20, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Turki, A.; Murad, M.; Karim, A. Do sustainable procurement practices improve organizational performance? Sustainability 2017, 9, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-X.; Yen, S.-Y. Top-management’s role in adopting green purchasing standards in high-tech industrial firms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F. Working with corporate social responsibility in Brazilian companies: The role of managers’ values in the maintenance of CSR cultures. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.R.; Trevino, L.K.; Cochran, P.L. Integrated and decoupled corporate social performance: Management commitments, external pressures, and corporate ethics practices. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Verbos, A.K.; Gerard, J.A.; Forshey, P.R.; Harding, C.S.; Miller, J.S. The positive ethical organization: Enacting a living code of ethics and ethical organizational identity. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.; Schubert, E. Perceptions of the ethical work climate and covenantal relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 36, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.W.; Frank, G.L.; Kemp, R.A. A multinational comparison of key ethical issues, helps and challenges in the purchasing and supply management profession: The key implications for business and the professions. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanja, I.N.; Achuora, J. Sustainable procurement practices and performance of procurement in food and beverages manufacturing firms in Kenya. Glob. Sci. J. 2020, 8, 1637–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Aila, O.; Ototo, R.N. Sustainable procurement concept: Does it all add up. Int. J. Dev. Sust. 2018, 7, 448–457. [Google Scholar]

- Eyaa, S.; Ntayi, M.J. Procurement practices and supply chain performance of SMEs in Kampala. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 2, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gudda, K.O.; Deya, J. The effect of supply chain management practices on the performance of Small and medium sized enterprises in Nairobi County, Kenya. Strateg. J. Bus. Chang. Manag. 2019, 6, 1870–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Karim, M.; Habes, E.M. Relationship between quality certification and financial & non-financial performance of organizations. J. Dev. Areas 2015, 49, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Oyuke, O.H.; Shale, N. Role of strategic procurement practices on organizational performance; A case study of Kenya National Audit Office County. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrgott, M.; Reimann, F.; Kaufmann, L.; Carter, C.R. Social sustainability in selecting emerging economy suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukappa, S.; Akintoye, A.; Egbu, C.; Suresh, S. Sustainable procurement strategies for competitive advantage: An empirical study. Manag. Procure. Law 2016, 169, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Davis, D.F. Grounding supply chain management in resource-advantage theory. J. Supp. Chain Manag. 2008, 44, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayle, M. A study of supply chain management practice in UK industrial SMEs. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2003, 8, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabegh, M.H.Z.; Ozturkoglu, Y.; Kim, T. Green supply chain management practices’ effect on the performance of Turkish business relationships. Int. J. Supply Oper. Manag. 2016, 2, 982–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Laari, S. Green supply chain management practices and firm performance: Evidence from Finland. 2016. Available online: https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/124787 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Meehan, J.; Bryde, D. Sustainable procurement practice. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 20, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Muir, S.; Hoque, Z. Measurement of sustainability performance in the public sector. Sust. Acc. Manag. Pol. J. 2014, 5, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, C.; Dowden, M. Strategic Sustainable Procurement: Law and Best Practice for the Public and Private Sectors; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Surajit, B. World class procurement practices and its impact on firm performance: A selected case study of an Indian manufacturing Firm. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 6, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, N.; Li, Z. Ethical procurement strategies for international aid non-government organizations. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2011, 16, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appolloni, A.; Sun, H.; Jia, F.; Li, X. Green Procurement in the private sector: A state of the art review between 1996 and 2013. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Jennings, M.M. The role of purchasing in corporate social responsibility: A structural equation analysis. J. Bus. Log. 2004, 25, 145–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.J.; Paulraj, A.; Lado, A.A. Strategic purchasing, supply management, and firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.H.; Amran, A.; Halim, H.A. Ethical and socially responsible practices among SME owner-managers: Proposing a multi-ethnic assessment. J. Southeast Asian Res. 2012, 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyabi, Y.; Barzegar, G.; Kohestani, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on Iranian SME financial performance. J. Soc. Issues Humanit. 2013, 1, 2345–2633. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organisational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.L.; Demirbag, M.; Bayraktar, E.; Tatoglu, E.; Zaim, S. The impact of supply chain management practices on performance of SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-S.; Thapa, B. Relationship of ethical leadership, corporate social responsibility and organizational performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 447. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Fahrbach, C.M. Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.J.; Seaman, A.E. The Influence of Ethical Leadership on Managerial Performance: Mediating Effects of Mindfulness and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2016, 32, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Lai, K. Corporate social responsibility practices and performance improvement among Chinese national state-owned enterprises. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Joshi, A.W. Corporate ecological responsiveness: Antecedent effects of institutional pressure and top management commitment and their impact on organizational performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013, 22, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeck, K.D.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.J. Ethical codes of conduct and organizational context: A study of the relationship between codes of conduct, employee behaviour and organizational values. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Mordán, N.; Frías-Aceituno, J.V. Transparency as a determinant of local financial condition. In Global Perspectives on Risk Management and Accounting in the Public Sector; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 202–225. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Huang, W.; Gao, Y.; Ansett, S.; Xu, S. Can socially responsible leaders drive Chinese firm performance. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Weber, T.; Kelloway, E.K. Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes: A field experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Patel, P.C.; Lepak, D.P.; Gould-Williams, J.S. Unlocking the black box: Exploring the link between high-performance work systems and performance. J. App. Psych. 2011, 96, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanchian, M.; Hussein, N.; Noordin, F.; Taherdoost, H. The relationship between ethical leadership, leadership effectiveness and organizational performance: A review of literature in SMEs context. Eur. Bus. Manag. 2016, 2, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Arham, A.; Boucher, C.; Muenjohn, N. Leadership and entrepreneurial success: A study of SMEs in Malaysia. World J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Valdiserri, G.A.; Wilson, J.L. The study of leadership in small business organizations: Impact on profitability and organizational success. Entrep. Exec. 2010, 15, 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, F.; Isiaka, S.B.; Kadiri, I.B. Business ethics and employees satisfaction in selected micro and small enterprises in Ilorin Metropolis, Kwara State, Nigeria. Kiu J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Chung, J.E. The roles of business ethics in conflict management in small retailer–supplier business relationships. J. Smal. Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.; Jabeen, F. Ethical climate, corporate social responsibility and organizational performance: Evidence from the UAE public sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elçi, M.; Alpkan, L. The impact of perceived organizational ethical climate on work satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.K.; Choi, B.K. How an organization’s ethical climate contributes to customer satisfaction and financial performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2014, 17, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurrian, R.C.; Matulich, E. Building customer value and profitability with business ethics. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2006, 4, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, F.; Mulki, J.P.; Solomon, P. The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intention, and job performance. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2006, 26, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, O.; Even-Zohar, S. Withdrawal behaviors syndrome: An ethical perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Hsieh, H.H. Toward a better understanding of the link between ethical climate and job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.S. Matching ethical work climate to in-role and extra-role behaviors in a collectivist work setting. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Padron, T.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R. Exploiting innovative opportunities in global purchasing: An assessment of ethical climate and relationship performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Wynn, P. The impact of ethical climate on job satisfaction, and commitment in Nigeria. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.H. Doing Well By Doing Good—A study of ethical and socially responsible practices among entrepreneurial ventures in an emerging economy. Front. Entrep. Res. 2009, 29, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, D.P.; Jennings, M.M.; Greene, S.M. Anderson’s Business Law and the Legal Environment, Comprehensive Volume, 23rd ed.; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Donker, H.; Poff, D.; Zahir, S. Corporate values, codes of ethics, and firm performance: A look at the Canadian context. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilman, H.; Gorondutse, A.H. Relationship between perceived ethics and Trust of Business Social Responsibility (BSR) on performance of SMEs in Nigeria. Middle-East. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Haron, H.; Ismail, I.; Oda, S. Ethics, corporate social responsibility and the use of advisory services provided by SMEs: Lessons learnt from Japan. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 20, 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric theory McGraw-Hill New York. In The Role of University in the Development of Entrepreneurial Vocations: A Spanish Study; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S. Ethical role of the manager. In Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris, S.; Tzempelikos, N. Conceptualization and measurement of key account management orientation. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2012, 5, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Schwepker, H.C. Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Victor, B.; Bronson, J.W. The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 73, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.G. Measuring performance of small-and-medium sized enterprises: The grounded theory approach. J. Bus. Public Aff. 2008, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesneau, D.A.; Gartner, W.B. A profile of new venture success and failure in an emerging industry. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.; Reichel, A. Identifying performance measures of small ventures—The case of the tourism industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváthová, E. Does environmental performance affect financial performance? A meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzempelikos, N. Top management commitment and involvement and their link to key account management effectiveness. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C.D.; Larcker, D.F. Measuring the impact of quality initiatives on firm financial performance. Adv. Manag. Organ. Qual. 1996, 1, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Z. Linking environmental uncertainty to non-financial performance measures and performance: A research note. Br. Account. Rev. 2005, 37, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Southend oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Small and Medium Enterprises General Authority (Monsha’at). 2020. Available online: https://www.monshaat.gov.sa/ (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Saudi Arabia Business Directory. Small Business in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. 2020. Available online: https://www.saudiayp.com/category/Small_business/city:Jeddah (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Meth. 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Vivier, E. A tough line to work through: Ethical ambiguities in a South African SME. Afr. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 7, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. The impact of ethics on the availability of trade credit to new small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 30, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, A.; Alajmi, S. The development of Saudi Arabian Entrepreneurship and Knowledge society. Int. J. Manag. Excel. 2017, 9, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algumzi, A. The impact of Islamic Culture on Business Ethics: Saudi Arabia and the Practice of Wasta. Ph.D. Thesis, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C. Business ethics and customer stakeholders. Acad. Manag. Persp. 2004, 18, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top management’s ethical commitment. | Top managers of this company regularly show that they care about ethics. | 0.723 | Trevino et al. [33] | |

| Top managers of this company are models of ethical behaviour. | 0.789 | |||

| Ethical behaviour is the norm in our company. | 0.885 | |||

| Top managers guide decision making in an ethical direction. | 0.912 | |||

| Ethical Climate. | The effect of decisions on the customer are a primary concern in this company. | 0.888 | Trevino et al. [33] Victor and Cullen [32] | |

| People in this company are actively concerned about the customer’s and the public’s interest. | 0.820 | |||

| The effect of decisions on the public are a primary concern in this company. | 0.777 | |||

| People in this company have a strong sense of responsibility to the outside community. | 0.718 | |||

| It is expected that everyone is cared for when making decisions in company organization. | 0.807 | |||

| In our company, people look out for each other’s good. | 0.835 | |||

| What is best for everyone is a primary concern in our company. | 0.736 | |||

| The most important concern is the good of all people in our company. | 0.868 | |||

| People are very concerned about what is generally best for themselves in our company. | 0.832 | |||

| Financial performance. | Our company financially benefitted by reducing overall costs. | 0.751 | Islam et al. [59] | |

| Our company is financially benefitted by increasing profits. | 0.704 | |||

| Our company is financially benefitted by increasing sales. | 0.720 | |||

| Our company financially benefitted by improving the Return of Assets. | 0.701 | |||

| Our company financially benefitted by increasing market share. | 0.827 | |||

| Non-financial performance. | Improved our company’s on-time delivery. | 0.889 | Islam et al. [59] | |

| Reduced our company waste. | 0.928 | |||

| Reduced our customer’s complaints. | 0.911 | |||

| Increased our management’s overall commitment. | 0.845 | |||

| Improved documentation. | 0.833 | |||

| Increased the company’s image. | 0.773 | |||

| Improved our company’s internal efficiency | 0.765 | |||

| Improved our company’s transparency | 0.790 | |||

| Improved our company’s productivity | 0.809 | |||

| Improved our company’s social and environmental responsibilities | 0.795 | |||

| Sustainable Procurement Practices | Environment | Uses a life-cycle analysis to evaluate the environmental friendliness of products and packaging. | 0.784 | Carter and Jennings [73] |

| Participates in the design of products for disassembly. | 0.763 | |||

| Asks suppliers to commit to waste reduction goals. | 0.790 | |||

| Participates in the design of products for recycling or reuse. | 0.766 | |||

| Reduces packaging material. | 0.789 | |||

| Human Rights | Visits suppliers’ plants to ensure that they are not using sweatshop labor. | 0.856 | ||

| Ensures that suppliers comply with child labor laws. | 0.829 | |||

| Asks suppliers to pay a ‘living wage’ greater than a country’s or region’s minimum wage. | 0.875 | |||

| Diversity | We purchase from minority and women-owned business enterprise (MWBE) suppliers. | 0.786 | ||

| We have a formal minority and women-owned business enterprise (MWBE) supplier purchase program. | 0.782 | |||

| Philanthropy | Donates to philanthropic organizations. | 0.701 | ||

| Volunteers at local charities. | 0.718 | |||

| Safety | Ensures the safe, incoming movement of products to our facilities. | 0.716 | ||

| Ensures that suppliers’ location is operated in a safe manner. | 0.702 | |||

| Purchase from Micro firms | Purchases from micro suppliers | 0.725 | Lindgreen et al. [45] | |

| Purchases from local suppliers | 0.701 | |||

| ME | SD | CA | CR | AVE | TMEC | EC | SPP | NFP | FP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMEC | 3.91 | 0.829 | 0.848 | 0.899 | 0.691 | 0.831 | ||||

| EC | 3.63 | 0.873 | 0.934 | 0.945 | 0.658 | 0.552 ** | 0.811 | |||

| SPP | 3.12 | 0.952 | 0.953 | 0.958 | 0.591 | 0.557 ** | 0.572 ** | 0.769 | ||

| NFP | 3.55 | 0.736 | 0.951 | 0.958 | 0.698 | 0.615 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.701 ** | 0.836 | |

| FP | 3.67 | 0.610 | 0.797 | 0.857 | 0.547 | 0.522 ** | 0.609 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.739 |

| Region | Total Number of SMEs & (%) a | Sample SMEs & (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Region (Riyadh and Qassim) | 287,088 (31.2%) | 38 (32.3%) |

| West Region (Makkah, Madinah and Tabuk) | 303,385 (33%) | 40 (34.0%) |

| Southern Region (Asir, Jazan, Najran and Baha) | 137,712 (15%) | 16 (13.7%) |

| Eastern Region (Eastern Province) | 135,185 (14.7%) | 17 (14.5%) |

| Northern Region (Northern Boarders, Hail and Jouf) | 55,787 (6%) | 6 (5.5%) |

| Constructs | SPP | NFP | FP |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMEC | 1.478 | ||

| EC | 1.478 | ||

| TMEC | 1.696 | 1.833 | |

| EC | 1.739 | 2.050 | |

| SPP | 1.751 | 2.166 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficients | Total Effects | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | TMEP -> EC | 0.478 | 0.569 *** | 0.569 *** | Supported |

| H2 | TMEP -> SPP | 0.148 | 0.353 *** | 0.573 *** | Supported |

| H3 | EC -> SPP | 0.177 | 0.386 *** | 0.386 *** | Supported |

| H4 | SPP -> FP | 0.003 | −0.063 ns | 0.039 ns | Not supported |

| H5 | SPP -> NFP | 0.237 | 0.386 *** | 0.386 *** | Supported |

| H6 | NFP -> FP | 0.048 | 0.265 * | 0.265 * | Supported |

| H7 | TMEP -> FP | 0.046 | 0.210 * | 0.549 *** | Supported |

| H8 | TMEP -> NFP | 0.081 | 0.221 ** | 0.632 *** | Supported |

| H13 | EC -> FP | 0.123 | 0.364 ** | 0.468 *** | Supported |

| H14 | EC->NFP | 0.179 | 0.334 *** | 0.483 *** | Supported |

| H9 | TMEP -> EC -> FP | 0.207 ** | Supported | ||

| H10 | TMEP -> EC -> NFP | 0.190 ** | Supported | ||

| H11 | TMEP -> SPP -> FP | −0.022 ns | Not supported | ||

| H12 | TMEP -> SPP -> NFP | 0.136 ** | Supported | ||

| H13 | TMEP -> NFP -> FP | 0.059 ns | Not supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazharul Islam, M.; Alharthi, M. Relationships among Ethical Commitment, Ethical Climate, Sustainable Procurement Practices, and SME Performance: An PLS-SEM Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310168

Mazharul Islam M, Alharthi M. Relationships among Ethical Commitment, Ethical Climate, Sustainable Procurement Practices, and SME Performance: An PLS-SEM Analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310168

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazharul Islam, Md., and Majed Alharthi. 2020. "Relationships among Ethical Commitment, Ethical Climate, Sustainable Procurement Practices, and SME Performance: An PLS-SEM Analysis" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310168

APA StyleMazharul Islam, M., & Alharthi, M. (2020). Relationships among Ethical Commitment, Ethical Climate, Sustainable Procurement Practices, and SME Performance: An PLS-SEM Analysis. Sustainability, 12(23), 10168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310168