Abstract

Among the Sustainable Development Objectives adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, is the 12th objective of Ensuring sustainable production and consumption patterns which aims to promote the efficient use of resources, energy efficiency, sustainable infrastructures, access to basic services, ecological support, decent jobs; and a better quality of life for all. In this line, our study illustrates a real case of farm producers who propose to transform the farm into an ecological entity with aim of safe and quality food production based on the sustainable production techniques and processes. This research outlines the market study that clarifies which consumers’ perceptions could be suitable for the ecological products derived from the organic bovine cattle. The primary data were obtained from the questionnaire survey conducted at supermarkets in Spain. The research sample comprised 330 respondents from Andalusia region. Results proved that the importance of the perceived value of products derived from organic beef was established in the following way: Price > Ethics > Health > Hedonism > Quality.

1. Introduction

Currently, producers and companies have been incorporated as fundamental elements for the fulfilment of the objectives of sustainable development. These goals were approved in September 2015 by the General Assembly of the United Nations. Among them, objective number 12 seeks to “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” by promoting the correct use of resources; energy efficiency; sustainable infrastructure; access to basic services, ecological support and decent jobs; and a better quality of life for all. The application of sustainable development helps to achieve general development plans, reduce future economic, environmental and social costs, increase economic competitiveness and reduce poverty [1].

The aim of sustainable consumption and production is to make more and better things with fewer resources, thus increasing the net profits and welfare from economic activities by reducing the use of resources, degradation and pollution throughout the products’ life cycles and simultaneously achieving a better quality of life. This process involves various stakeholders, including businesses, consumers, scientists, researchers, retailers, media and development cooperation agencies that are responsible for the formulation of relevant policies. Sustainable production and consumption also require a systemic approach and cooperation among the participants in the supply chain, from the producer to the final consumer. It consists of engaging consumers through awareness raising and education on consumption and sustainable ways of life by providing them with proper standards and labels and participating in sustainable public procurement, among others [1].

Taking all this into account, the responsible parties of a property located in the south of Spain raised the possibility of transforming a part of it for using in ecological production, i.e., introducing ecological cattle, with the purpose of producing safe and high-quality food through the application of sustainable production processes and techniques. In this sense, producers, beyond seeking to achieve greater profitability with the possible transformation of the estate, are committed to the long-term common good as they subscribe to the SDO [1].

In turn, these goals are connected with new trends in the market since social, ethical and environmental matters arising from the acquisition of products and services are increasingly taken into account in purchase and consumption behavior. Some of the issues which many concerned citizens face when defending the values in which they believe are how products are made and who benefits or is harmed from their consumption [2]. A greater demanding for and more conscious understanding of the social and environmental impacts of consumption has indeed been gaining momentum. This has come to be called socially responsible consumption (SRC). One of the key aspects to stimulating this type of consumption and thus fostering the production of sustainable products by the companies will be to understand the consumers’ assigned values. Therefore, this research can improve scientific knowledge about the perceptions of consumers and the socially responsible consumption of such products.

1.1. Socially Responsible Consumption: A New Way of Understanding the Consumer

Recently, consuming was synonymous with spending, wasting or destroying. Consumption has come to be synonymous with environmental destruction in many parts of the planet. However, the enhancement of the social and environmental considerations of consumers is reflected in a new way of understanding consumers. The well-being that a product can provide and the specific rules of conduct when obtaining it are no longer important. Initially, the SRC was associated with a desire to help other people, although this is not obtained in the form of any personal benefit [3].

In terms of providing the main definitions given in recent years about SRC, we would say that one of the first to define it was [4] who stated the following: a socially responsible consumer is one who takes into account the consequences which, in society, may derive from its private consumption, or one who tries to use his acquisition capacity to foster changes in society. For other researchers, SRC has a focus on environmental aspects—such is the case of [5,6], which define the responsible consumer as the one that takes into account the environmental problems that may arise from their capacity of purchase.

Instead, Ref. [7] includes a broader definition, which was inspired by Webster. In it, a socially responsible consumer is defined as the one who acquires goods and services considered to have a positive impact (or less negative) on the environment, using their power of acquisition to express current social problems. According to [8], SRC has two dimensions: environmental and social.

A socially responsible consumer avoids purchasing products or services from shops or companies where it is known that with their practices they can harm society. They are seeking a way through which active companies can contribute to improving the lives of citizens [9]. This is a very limited approach because it conceives the SRC only via the choice of suitable companies. In short, it seeks what can provide a positive or less negative impact, both in environmental issues and social problems that are topical. Other authors [10] with a very limited perspective indicated that the SRC concept was exclusively linked to fair trade. However, as we will continue to see, more dimensions can be contemplated in its definition.

As can be seen in the different contributions of the various authors, it is difficult to find a consensus on the definition of the term SRC. Indeed, there are various approaches involved in the study of this construct. Ethical consumption and green consumption, where the latter is linked to environmental and ecological aspects, are two of the most representative conceptualizations in the bibliographical revisions of the term.

Ethical consumption, which was noted as being a partial view of the SRC, refers to the moral principles or values that govern the conduct of an individual that uses, gets or discards products or services and whose actions may or may not have impact on others. According to [11], little attention has been paid to the ethical aspects that influence consumer purchase decisions. In exchange, the authors of [12,13] define it as the degree to which the consumer prioritizes their own ethical considerations when choosing the product. In addition, in [14] it is considered that an ethical consumer is the one who buys products that are not harmful to the environment or health. According to [15], for this type of consumption, one should leave aside questions on the environment.

On the other hand, the partial approach to SRC as green consumption is understood as the set of beliefs and values that are intended to support a greater good, prompting consumer [16,17]. According to [18], consumer products that are harmful to the health of others and damaging to the environment should be prohibited. Additionally, consumers should avoid eating such foods in which animal welfare has not been respected, or those which have been obtained using disproportionate energy expenditures. Initially, the ethical approach of SRC differed from green consumption in which ethical issues comprised a greater number of aspects such that the decisions that consumers had to make were more complex [19]. For this reason and to balance the load of moral conscience, Ref. [20] wanted to collect many of the ethical considerations, such as animal welfare, fair trade and working conditions, in the concept of green consumption.

1.2. Comparative Scales to Measure Socially Responsible Consumption

As we have seen in the previous section, if we face the impossibility to obtain a categorical definition of CRS, there are various scales of measurement of the construct studied according to the given different approaches and different numbers of items.

The first scale used to measure SRC was [3], as evidenced by some studies [5,21]. Even though this scale is used in sociology to measure the degree of social responsibility of individuals in their daily lives, it is not suitable to study the behaviors of consumers since it does not contain any items in this regard [22]. Later, the authors of [4,23] used scales that reflect the environmental performance of the consumer (e.g., purchases of unleaded petrol, the use of detergents with less phosphates, etc.).

Later, in [7,8] the first attempt was made to introduce social aspects into a scale on SRC, which was considered as being more robust to measure the construct. The aspects include two dimensions (social and environmental) and should incorporate items that reflect the ethical behavioral considerations of Crane [24]. Years later, in [25] a scale was proposed with four dimensions: considerations on the product itself, the way of marketing, the behavior of the firm or company, and, finally, the country of origin.

In 2006 in [24], when determining if French consumers shared the same ecological and social concerns as their counterparts in the United States, a scale was proposed of five dimensions that encompasses the social and environmental concerns of individuals: (1) concern about the consequences of business practices, (2) the acquisition of products where part of their revenue goes to social causes, (3) support for small businesses, (4) attention to the geographical origin of the products and (5) the volume of consumption [17]. According to [26], it also included recycling habits, modes of consumption (such as the use of public transport) and respecting the environment in the scale of [24].

The study on the behaviors of consumers is fully justified because it has become the essential economic system [27]. In the case of our research, it would be interesting to explain and predict the behaviors of consumers with respect to the organic products in order to know why these socially responsible consumers buy certain products that are derived from organic cattle, how their preferences are formed, and what factors would influence their purchasing decisions [28].

An important aspect in the study of the behaviors of consumers is the fact that the consumer searches, beyond the product itself, can provide you with the same benefits or services. In this case, the benefits that could increase the consumption of organic products, particularly organic beef derivatives, are perceived through the characteristics or attributes of buying the goods. For this reason, it would be interesting to know the needs, desires, perceptions, attitudes, intentions, and other psychological and social aspects of consumers towards this type of product (for example, nutrition, health, appearance, physical, conservation of nature, etc.).

If we have more and better knowledge of these socially responsible consumers and understand what value is given to organic products, companies might be more efficient in meeting the preferences of consumers.

1.3. The Concept of Perceived Value

In this line of thought, to achieve the objective of the study, it should be highlighted that one of the most successful and recognized concepts in the field of marketing is perceived value (PV). Its application has favored different fields of study, such as consumer behavior, strategic marketing, pricing policy, and so on. The reasons for this recognition tend to be based on its relationship with the loyalty of customers [29], in its relevant role in building relationships and its nature as a factor for the achievement of competitive advantages [30].

The PV is another complex term that seems to be defined as an exchange or trade-off between benefits and costs. Far from being a perfectly defined term, the PV is subject to an ongoing debate with respect to both its definition and the dimensions that constitute it.

It is important to highlight that an undisputed definition of the concept of PV has not been categorically established yet, as it has been shown historically in the literature of this discipline. Several authors have pointed out the need for more research in this area [31,32,33,34,35]. However, we cannot deny the extensive existence of work, studies and research in this line. This lack of unanimity is due to reasons such as the complexity [35,36,37], subjectivity [38], dynamic [29,34,35,39,40,41] or the polysemic characteristics of this concept [30].

The diversity of the concept, including the richness and variety that it provokes and the certain polysemy of the concept of value, makes it difficult to have an accurate and rigorous approach in this regard, and we can mention that “the existence of so many definitions of value makes a scientific discourse difficult” [34].

Nevertheless, despite the time that elapsed, the most widespread definition is the one posed by [42], which will serve as a basis for this research:

“(…) the perceived value is the overall assessment of the consumer of the usefulness of a product, based on the perception of what is received and what is delivered.”

It refers to this concept of PV as both a balance to what the consumer perceives regarding the benefits and costs of a product.

1.3.1. Dimensions of Perceived Value

The dimensional structure of the latter provokes recognizing a two-dimensional concept of PV. Different investigations indicate that perceived value is a comparison between what consumers receive and what they deliver when buying a product or service [43].

This comparison can be represented by the following equation [44]:

Perceived value = (perceived benefits)/(perceived costs)

Therefore, it can be said that two general components of perceived value are the benefits and costs that the customer will have when purchasing a product or service. However, in the approaches on the dimensional structure of the PV, most of the works are based on the approach of Zeithaml. This approach differentiates between the benefits and costs by classifying them into three categories that collect many previously given aspects that were previously given (functional, social and emotional benefits and costs) [45,46] by defining how they are functionally related to the utility, their associations with the stereotypes of one or several social groups (demographics, socioeconomics, cultural-ethnic, etc.) and how they are emotionally associated with feelings or emotional states [47].

In short, the concept of PV will be understood as a trade-off between the benefits (what is received) and the costs (what is delivered) that are perceived by consumers of products derived from organic beef. This is precisely the approach that will be developed below.

1.3.2. Benefits Perceived by the Consumers of Organic Products

Perceived Quality

In the field of food, in which we focus our case study, the consumer tends to rely on senses to detect the factors of quality, which can be divided into the categories of flavor and texture [48]. With products derived from organic beef, the flavor and texture could be the features that are relatively appreciated by consumers as components of quality [49].

The following Table 1 presents some metrics that were used in previous studies to assess taste and texture as indicators of quality.

Table 1.

Concerning the perceived quality metrics.

Perceived Hedonism

Indicators of the hedonistic dimension, according to those proposed by [43,55], were the moods generated by eating such organic cattle products and the pleasure in the consumer. Some of the metrics that were used in previous studies on hedonism are given in the following Table 2.

Table 2.

Metrics relating to the perceived hedonism.

Perceived Ethics

According to [49,50,51,52,55,56], the protection of the environment and the payment of one price greater than the production costs in developing countries are indicators of fair trade, which, in our case, distinguish it from the conventional indicators of products derived from bovine animals in organic production. Some of the indicators used to measure the ethics of the PV refer to both the protection of the environment and a premium payment to farmers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Concerning the perceived ethics metrics.

In the case of the health dimension, the most relevant indicators will be the beneficial effects on human health (Table 4).

Table 4.

Perceived health metrics.

1.3.3. Costs Perceived by Consumers of Organic Products

Perceived Price

Finally, the price represents the negative dimension or the costs that are paid by a consumer. For their measurement, according to the literature review, we, on the one hand, have the indicators of the comparison of prices for similar products, which was proposed by [49,58,59] and on the other hand, the proposal of [32,43,53,55,60,61,62,63,64,65] and for the comparison between price and quality (see Table 5). All this coincides with the proposal in that consumers evaluate prices not absolutely, but in comparison with a reference price [66].

Table 5.

Concerning the perceived price metrics.

Considering that consumerism is a distinguishing trait of current capitalism [67] and human beings, consumers have their own criteria and tools for it, since through the small gestures of daily consumption and questioning the established systems, society has a fundamental and powerful tool at the time of purchase to encourage social change [68]. This would encourage consumption based on personal convictions that promotes sustainable development and a search for meaning among other things, beyond the mere benefits of consumption itself. In this line, companies should line up with this market through sustainable production, causing them to be a tool of social change contributing to solving different social, ethical and environmental problems affecting the citizens. Some of these problems are collected in the objectives of sustainable development (SDO) and the European Horizon 2020 strategy (EU2020 strategy), which aims to revive the European economy and face different challenges and global challenges such as climate change, food security, the fight against human and animals diseases, the ageing of the population and population growth.

In should be considered that producing involves the exploitation of natural resources such as the increase in energy demand, the waste or shortage of water [69], and that current forecasts indicate that the world’s population will grow exponentially in the coming years. The need for a sustainable and ecological production that will help to improve and conserve natural resources on which the well-being of present and future generations depends will be a subject of extreme relevance since the exploitation of them is expected to be much more intense and that these resources are limited [70].

Undoubtedly, one of the psychographic variables with the greatest relevance to predicting consumption behaviors is attitude [71]. Different attitudes can influence an individual’s behavior both positively and negatively. The case of the responsible consumption study has traditionally focused on the so-called green or ecological consumers [72]—a predominant dimension at the beginning of responsible consumption studies—defined as those who express an attitude of environmental concern when purchasing their products or services [73]. In the bibliography review, one of the most common attitudes to understanding green consumption behavior is the attitude of environmental concern or perceived value [74,75,76]. This partially justifies that many investigations have studied specific consumer acts related to environmental aspects [77].

In this sense, and with the idea of minimizing the gap between responsible consumption and the perceived value of the products consumed, this research aims to respond with what type of variables could motivate positive changes in consumer behavior, and thus influence them in advertising messages [78]. It is important not only to raise awareness but also to facilitate the means to be able to materialize. This is precisely one of the concerns of Social Marketing, an area that could be the key to working on all these issues. Thus, we should consider aspects such as: How do social campaigns that promote responsible consumption fail? Why do these occur with different intensities?

Based on a theoretical review on the concepts of responsible consumption and perceived value, and considering our knowledge objectives, we come to the formulation of the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

The different dimensions of the perceived value of organic bovine products have a significant effect on socially responsible consumption.

Backgrounds presented and the theoretical revision that precedes these lines served as the basis for the design of an empirical research. In order to carry out the research, both the metric instruments used and the sample design will be described. The way in which the research data were obtained and processed will be collected as well.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

The primary data were collected through a questionnaire divided into four blocks (Appendix A). For its design, according to the objective of the research, we selected scales to measure socially responsible consumption, perceived value, and social desirability, the last of which was done to avoid possible social bias in the responses given and the variables of socio-demographic characteristics.

2.2. Pre-Test

Initially, a pre-test was made on a sample population of ten individuals with the intention of knowing how the questionnaire would run through a prior trial or pilot. After the completion and analysis of the pre-test, some modifications were carried out. To continue with our study, we decided to distribute this questionnaire consisting of 40 questions.

2.3. Sampling

Once the pre-test was made, using the total sample of the research, we distributed it for two weeks at the gates of the main supermarkets in Seville and Córdoba (Spain). In this way, a total of 330 people were surveyed, most of whom were women (70% of the surveyed individuals), in the major supermarkets in the mentioned cities in the South of Spain. In this sense, the technical data of the sample in our study (Table 6) were set as follows.

Table 6.

Research design.

The sample was previously designed based on a previously defined and representative population of consumers from the Andalusia region (Spain). To do this, we opted for a type of quota sampling widely used in opinion polls and based on knowledge of the strata of the population, and the most representative individuals of the research carried out. As age and gender have an influence on the socially responsible consumption [79,80], we have used quota sampling. It was designed according to the census data from the Andalusian Institute of Statistics. In this way, the sampling was representative (see Table 7). Taking into account the requirements of our research and the available quotas, a sample of 330 individuals was finally proposed. It should be noted that they responded to the necessary profile in our research (70% women vs. 30% men).

Table 7.

Sample proposal required for research.

CN indicated the size which the sample must reach to accept the model fit on a statistical basis. The acceptable lower limit is usually around 200, so in the case of the research developed we can say that the adjustment is acceptable (267.7). In turn, SRMR values below 0.05 indicate a good fit of the model, as would be in the developed case (0.0363). The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) and Parsimony Goodness of Fit Index (PGFI) evaluate the degree to which variances and covariance in the model correctly reproduce the original variance and covariance matrix. The first, GFI, does so globally, the second, AGFI, is adjusted to degrees of freedom, and the third, PGFI, is adjusted to the complexity of the model. The first two must exceed the value of 0.9 as was the case (GFI—0.929 and AGFI—0.906), while the third could be much lower (PGFI—0.687) and still the model has a very good fit (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Critical N (CN) parameter and Goodness of Fit (GFI) index.

There are many possible tuning indexes, and none of them is enough by itself to conclude whether or not the model fits the data. To decide on the suitability of the model [81,82], a combination of different adjustment rates, such as Chi-Squared, RMSEA, ECVI, SRMR, GFI and CFI, is used. Following this indication together with the representativeness of the sample described above, it could be determined that the proposed model conforms to the research data and is not affected by the sample size.

3. Results

At first, the database was purified by validating the metric scales that are used to measure the concepts of socially responsible consumption (SRC) and perceived value (PV). Then, we used structural equations modelling (SEM) to model the pattern of the relationships between the dimensions that make up the perceived value and socially responsible consumption, and we analysed the variance using partial least squares modelling.

3.1. Purification of the Sample: The Social Desirability Bias

A relevant correlation between the scale of DS and the metric scales of SRC and VP was made where correlations were obtained for the object of study. This verified that both the VP and SRC scale scores, along with the social desirability, presented a very low correlation (as r < 0.5). Therefore, DS bias did not occur in the case of research carried out for either of the metrics that was considered. Therefore, the database did not need debugging.

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis in the Metrics of SRC and PV

Once the relevant factor analyses were made, both the SRC and PV metric scales were validated in our sample of 330 individuals. In this sense, the SRC metrics were extracted in five dimensions that referenced the concern for the consequences of business practices, the acquisition of products where part of their income goes to a social cause, support for small businesses, attention to the geographical origin of products and the restriction of consumption volume. Similarly, five other dimensions that alluded to the quality, hedonism, ethics, health and price were obtained from the PV metric. To continue with our study of the behavior of socially responsible consumers in relation to the perceived value of products derived from ecological bovine cattle, it gave way to a structural model that linked the perceived values of such products (comprised of the five dimensions listed) with socially responsible consumption (formed by the other five dimensions described above).

3.3. Analysis of the Proposed Measurement Model: PV as a Precursor of the SRC

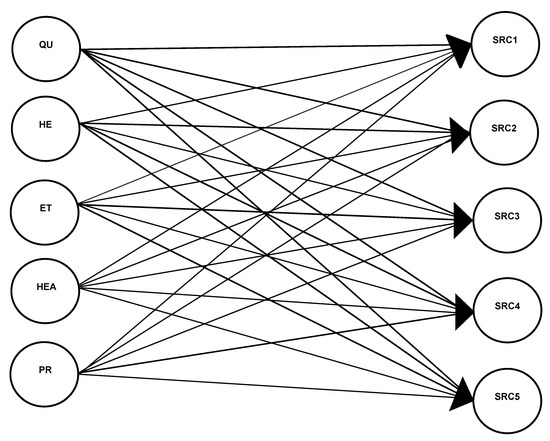

A multivariate second-generation analysis was carried out using a structural equations modelling (SEM) approach [83]. The goal of the modelling was to know if the perceived value of products of organic beef could be historically defined as consumption socially responsible or, in other words, if the dimensions that define this type of socially responsible consumption were dependent on the dimensions that make up the perceived value in such products (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed structural model that relates VP and SRC. VP includes quality (QU), hedonism (HE), ethics (ET), health (HEA) and price (PR), while SRC includes behavior of the company (SRC1), products related to a cause (SRC2), small businesses (SRC3), geographical origin (SRC4) and volume of consumption (SRC5). Source: Own processing, 2017.

We took into account that this type of model is interpreted in two stages [84], thus ensuring that we get valid and reliable measures before arriving at conclusions.

The two different stages were as follows:

- (i)

- Individual reliability of the item

To assess the reliability of the individual items that make up both the PV and SRC, we examined the charges (λ) or simple correlations of the indicators with their respective constructs (Table 9). We adopted the more accepted and widespread rule of thumb that says that to accept a flag as part of a construct, it must have a load equal to or greater than λ ≥ 0.707 [85], which implies that the variance shared between the construct and its indicators is greater than the variance of the error.

Table 9.

Loads (λ) of the indicators with their respective constructs.

On the other hand, the assessment of the reliability of a construct allows us to verify the internal consistency that is present in all indicators to measure the defined concept; i.e., the thoroughness of the measure is evaluated. This is done using two indicators, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and the reliability of the construct (ρc), with the latter being similar to Cronbach’s alpha despite the fact that some authors defend the reliability of the construct as superior because they claim that it is a more general measure [86].

We use the Cronbach’s alpha and the reliability as measures of the internal consistency that are applicable to latent variables with reflective indicators [87]. The results are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Cronbach’s alpha values and composite reliability obtained for the proposed measurement model.

In view of the results that are obtained, we can confirm there is internal consistency in our modelled object of study. To carry out convergent validation, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE). As you can see in Table 11, all AVE values are greater than 0.5.

Table 11.

Average variance extracted (AVE) values obtained in the proposed measurement model.

Regarding the discriminant validity, in all cases, the square root of the AVE is higher than the correlation between each construct and the rest of those included in the model. Therefore, we can conclude positively (Table 12).

Table 12.

Values obtained to analyze the discriminant validity.

- (i)

- Assessment of the structural model assessing the magnitude and weight of the relationship between the different variables used.

A measure of the predictive power of a model is the R2 value for the dependent latent variables. As we can see from all the values in the following table (Table 13), they are all superior to 0.1. According to recommendations in [87], there would be no predictability problems in the model that has been proposed, if all relationships that are proposed measurement models are significant.

Table 13.

R-Square values in the structural model.

To clarify this result, we compare the t-statistics that were obtained (see Table 14) with the significance level threshold, and we claim that there is a high significance between all the relationships between perceived value and the five proposed dimensions that define socially responsible consumption (SRC1, SRC2, SRC3, SRC4 and SRC5). In particular, the most significant relationships will be the ones established between the dimension price that defines the perceived value and four of the five dimensions that make up socially responsible consumption. These relationships will be direct but negative in all the dimensions that define the socially responsible consumer. Although the price is not so negatively valued in the case of consumers who consider whether to buy products that support some specific cause. These consumers’ ethics are assessed to be above any other dimension of the perceived value of organic beef products.

Table 14.

Values of t-statistics and β coefficients obtained in the model.

The rest of the relationships are significant, with lower levels of significance existing for quality as perceived value and the five dimensions of socially responsible consumption. The inner dimensional quality as perceived value is established with respect to the other, more significant dimensions related to the geographical origin of the products.

Furthermore, to evaluate the path coefficients that were obtained or the standardized regression weights (β) (Table 14), the criterion proposed by [87] was taken into account. It states that these coefficients must reach at least one value of 0.2 to be significant, and they should ideally be above 0.3. In our case for the subject of study, all the obtained path coefficients (β) had values above the preferred threshold (0.2). Thereby, relying on the results obtained in this approach after the analysis of the model, we will present the main conclusions of this study.

In conclusion and returning to our goal of studying whether the perceived value could be a precedent of SRC, we can conclude from our results that it is true. In other words, at higher perceived value, there is also greater responsible consumption in all its manifestations. Therefore, for the promotion of a SRC, one of the possible lines of work could be to enhance advertising by companies [88] on these dimensions or an environmental education that would influence the need for the involvement of the whole of society in the common benefit, at all levels, both from small individual action—which is so often perceived ineffective—to the large institutional commitments. Moreover, advertising sustainable consumption is an important element for sustaining both social and environmental needs for future generations [89].

4. Conclusions

The results allowed us to accept this hypothesis, confirming the existence of a significant relationship between the perceived value of organic bovine products and responsible consumption. This therefore implies there is no single way of understanding the SRC, on the part of consumers, and that there is a significant relationship with how these products are perceived. Thanks to the extracted results, it was found that the consumers of Andalusia, one of the most important regions of Spain, are increasingly socially responsible in their purchasing process. In this sense, we find that the consumers of this study are socially responsible consumers who buy responsibly because the social and environmental issues arising from the admission and consumption of products and services are increasingly of concern to them. In this line, they are aware that their consumption can be the engine of social transformation. Among the benefits for them are those of generating social and environmental benefit, through their consumption process, beyond the fact of consuming. The results poured us outstanding information about consumer concerns in southern Spain. The study and analysis of this behaviour, closely linked to the individual’s conscience, should be of great interest since it enables us to learn how to evolve the traditional consumption patterns and reflect upon its consequences. In this way, it could facilitate both policies of social intervention and the design of business strategies for companies wishing to connect with consumer values and give them greater satisfaction.

Both the concept of and the metrics defining socially responsible consumption were clarified. This implies improving the scientific knowledge of new trends in the market and encountering increasingly more demanding consumers in the purchase process, who are knows as the socially responsible consumers. This is a consumer that adopts a series of social, ethical and environmental concerns. Therefore, after the review of the relevant literature, we clarified the concept of SRC, thus determining that we are faced with a complex definition construct. However, after analyzing the different metrics around it, we decided to define a socially responsible consumer by presenting five different ways to express this responsibility in their buying process.

In addition to knowing what value this type of consumer granted to possible products that may arise from an ecological transformation, it was necessary to define the concept of perceived value and the metric of the same design. In this sense, following the literature review, we concluded that the concept that best defines the PV is the difference between the benefits (that are received) and the costs (that are delivered) that are perceived by consumers when purchasing a product. The first finding, taking into account this definition and the difficulty of finding a PV metric built around products derived from organic beef, was the proposal and design of a five-dimensional metric.

Once we clarified both the concepts and metrics of SRC and PV, we proposed structural equations modelling that related both concepts. Through this, we know the value given to or perceived by the socially responsible consumer for this type of product.

The results led us to conclude that the different dimensions of the perceived value of products derived from organic beef partially have a positive and direct effect on socially responsible consumption. Therefore, if all the relations between the dimensions that define the perceived value and the five proposed dimensions that define the socially responsible consumption were significant, the dimension of perceived value price had a negative effect on this type of consumption, i.e., the consumer assigns a negative price to the products derived from organic beef.

Furthermore, the relationship between the price of the PV dimension and four of the five dimensions that make up consumption socially responsible are stronger. That is, it will be the dimension with the highest weight for the consumer in the process of purchasing products derived from organic beef. In particular, the dimensions are the relationship between the price and the relative dimensions, the concern about the consequences of business practices, support for small businesses, attention to the geographical origin of products and the restriction of consumption volume. While these relationships are direct, they will be negative, as indicated above.

This result could find its explanation in the consumer when comparing organic products with non-organic by punishing the increase in price, which tends to be linked to this type of organic products and, therefore, is perceived as a negative attribute. Sometimes, that increased price could be justified by the producer since the ecological stockbreeding deals with nature and therefore avoids the use of chemical compounds and the use of genetically modified species, thus representing major constraints on productivity. Another reason could be that raising outdoor livestock will lead to having a large expanse of land for a few animals, which would lead to an increase in the price.

Conversely, the price is not so negatively perceived in the case of consumers who value the products that they are purchasing, support or are linked with any particular cause. By assessing these consumers, we see that ethics are above any other dimension of the perceived value of organic beef products.

Taking into consideration that all established relationships are significant, the order of importance of the perceived value of products derived from organic beef was established in the following way:

Price > Ethics > Health > Hedonism > Quality

As it can be seen, the relationship that is given less value is the relative quality of the perceived value and the five dimensions of socially responsible consumption. The inside dimension quality of the perceived value is established with respect to the others, which is especially significantly related to the geographical origin of the products.

These results could provide us with a basis for working in a target way on these dimensions that are perceived by the consumer in such products. Therefore, the strategies of marketing companies that decide to offer organic beef by-products, including institutions seeking to promote a more responsible consumption, could adapt better.

There are several limitations that affect our research. The first of these has to do with the sample with which we have applied to address the market study. On the one hand, the fact of having been obtained by surveys in the cities of Cordoba and Seville (Spain) introduces a certain bias in the profile of the participants, given that not everyone has the same chance to participate. On the other hand, being restricted to these two Spanish cities’ sample, there may also be a cultural bias. A second limitation is related to the scales of SRC and PV that were employed. Although we tried to choose and design scales that reflect a greater diversity of behaviors that could be described as socially responsible and which faithfully address the concept of VP, this removes behaviors or domains that may have formed and might be interesting to include in the analysis but were otherwise not included.

Although studies on SRC are progressively finding greater relevance within consumer behavior literature, we are still faced with a topic that needs to be better understood. In this regard, the concept of SRC is something that must still be revised, both in the practices that shape it and also in its possible evolution over time. Future research should continue to explore the definition of scales and comparison of results obtained with existing ones. The comparison of culturally different samples should also be studied in this field, developing comparative studies that allow deepening the knowledge of factors or variables related to this type of consumption. In this regard, it is also advisable to study the relationship with profile variables that allow the establishing typologies of socially responsible consumers. Something entirely necessary for its promotion, facilitating the design of strategies more and better adapted to its target audience, from the institutions or from the companies themselves that contemplate this segment of the market.

In this line, it would also be very useful to study those factors that inhibit or facilitate socially responsible consumption behaviors. What limits conscious consumers from adopting more responsible consumer behaviors? To what extent do cultural traits influence this and why? Is information a key aspect of responsible purchasing decision making? If so, what role can new technologies play? To what extent can strategies such as the use of sustainable seals be facilitators of SRC? More research and new evidence on these aspects is at every point necessary for the design of policies that more effectively promote more committed consumption. It is not only important to raise awareness, but also to facilitate the means to be able to materialize change [88].

The desirability of studying the impact of certain sociocultural trends, such as the influence of consumerism or the new social movements that gravitate into the orbit of the avoidance of waste or the pursuit of sustainability, is also of interest. We may wonder about the extent to which the promotion of consumerism that proliferates in Western culture plays against more committed consumption, or if movements such as collaborative systems, platforms to sell between individuals or ecological orchards are creating greater awareness in the population.

One of the key points of studies on purchasing behaviors is the existence of a gap between intentions and actual behavior. Despite everything that has been advanced in the design of theoretical models, mainly in the field of psychology, we are still facing a controversial issue. Above all, we must deal with the thorny issue of how to measure real consumer behavior. All of this opens a necessary research front to further investigate the knowledge of the SRC. New methodologies also need to be explored.

Finally, further introspection into responsible consumer psychology is required. To what extent does the SRC respond to a concern about the consequences of consumption or, rather, to cool behavior or that which responds to the search for image, personal or group self-affirmation, or the construction of a personality? Or can we also ask ourselves why not all kinds of environmental awareness are a generator of SRC?

Currently, few deny the significant economic, social and environmental effects that are intimately linked to the phenomenon of consumption. We are also convinced of consumer power in markets. The so-called "vote with the portfolio" is increasingly understood as an important lever of change to lead companies towards more socially responsible actions. Hence, the study of SRC and PV as a precedent seems to us to be an object of socially urgent and relevant research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.P.-B., and R.E.-P.; methodology, J.J.P.-B., and R.E.-P.; software, J.J.P.-B., and R.E.-P.; validation, J.J.P.-B., and R.E.-P.; formal analysis, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P., and P.Š.; investigation, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P., and P.Š.; resources, J.J.P.-B., and R.E.-P.; data curation, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P., and P.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P., and P.Š.; writing—review and editing, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P., and P.Š.; visualization, P.Š.; supervision, P.Š.; project administration, J.J.P.-B., R.E.-P. and P.Š.; funding acquisition, P.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire Distributed in the Investigation

- MARKET STUDY RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION AND ECOLOGICAL PRODUCTS

- Mark with a cross where appropriate:

- Man ☐ Woman ☐

- AGE: ______________

- Córdoba ☐ Sevilla ☐

| P1 | I try not to buy products from companies that employ child labor. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P2 | I try not to buy products from companies that do not respect their employees. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P3 | I try not to buy products from companies or establishments closely related to political parties or ideologies that I censor. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P4 | I try not to buy products from companies that seriously damage the environment. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P5 | I try not to buy products from companies closely related to the mafia or some type of sect. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P6 | I buy some products that allocate a part of their price to a humanitarian cause. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P7 | I buy some products that allocate a part of their price to developing countries. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P8 | I buy some products that allocate a part of their price to a good cause. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P9 | I buy fair trade products. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P10 | I avoid doing all my purchases in large stores (for example: Carrefour, Mercadona, Media Markt, Zara, etc.) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P11 | I buy in small establishments (for example: bakeries, butchers, bookstores) as often as possible. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P12 | I help the survival of small businesses in my neighborhood through my purchases. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P13 | I go to the markets of supplies to support small farmers. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P14 | When I have to choose between a European product and one of different origin I do not choose the European one. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P15 | I prefer to buy Spanish cars. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P16 | I try to buy some Spanish fruits and vegetables. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P17 | I try to buy products made in my country. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P18 | I try to adjust my consumption to what is strictly necessary. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P19 | In general, I try to consume less. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P20 | I try not to buy things that I can do myself. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P21 | Organic beef has a flavor. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very bad Excellent |

| P22 | Organic beef has a texture and aroma. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very bad Excellent |

| P23 | The consumption of organic bovine meat improved my mood. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P24 | It was a pleasure to eat organic beef. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P25 | I am convinced that products derived from organic cattle are protecting the environment. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P26 | I am convinced that with these organic bovine products, a higher price is paid to the farmer. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P27 | The consumption of organic bovine products is beneficial for my body. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P28 | The consumption of organic beef does not imply any risk to my health. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P29 | In comparison with other types of meats, the monetary cost of organic beef is. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very low Very high |

| P30 | Organic beef has a reasonable monetary cost compared to its quality. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Totally disagree Totally agree |

| P31 | When I make a mistake I am always willing to admit it. 1 0 True False |

| P32 | I always try to practice what I preach. 1 0 True False |

| P33 | I never get upset when people ask me to return some favor they have made me. 1 0 True False |

| P34 | I never get irritated when people express ideas which are very different to mine. 1 0 True False |

| P35 | I have never deliberately said anything that could hurt someone’s feelings. 1 0 True False |

| P36 | Sometimes I like to gossip a little. 1 0 True False |

| P37 | On occasion I have taken advantage of someone. 1 0 True False |

| P38 | Sometimes I try to avenge myself instead of forgiving and forgetting what they have done to me. 1 0 True False |

| P39 | Sometimes I insist on doing things my way. 1 0 True False |

| P40 | Sometimes I feel like I am clumsy. 1 0 True False |

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Sustainable Consumption and Production. A Handbook for Policymakers; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; ISBN 978-92-807-3364-8. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4203.8569 (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- D’Astous, A.; Legendre, A. Understanding consumers’ ethical justifications: A scale for appraising consumers’ reasons for not behaving ethically. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L.; Lutterman, K.G. The traditional socially responsible personality. Public Opin. Q. 1968, 32, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E. Determining the characteristics of the socially conscious consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henion, K.E.; Wilson, W.H. The ecologically concerned consumer and locus of control. In Ecological Marketing; Karl, E.H., Kinnear, T.C., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA; Grid, Inc: Columbus, OH, USA, 1976; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Antil, J.H. Socially responsible consumers: Profile and implications for public policy. J. Macromark. 1984, 4, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: A cluster analytic approach and its implications for marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Will the real socially responsible consumer please step forward? Bus. Horiz. 1996, 39, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebzar, B.; Larbi, M.; Jahidi, R. Social responsibility of consumer case of products from the social economy in morocco. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nicholls, A.; Lee, N. Purchase decision-making in fair trade and the ethical purchase ‘gap’: Is there a fair trade ‘twix’? J. Strateg. Mark. 2006, 14, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J.; Muncy, J. Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.S.; Clarke, I. Culture, consumption and choice: Towards a conceptual relationship. J. Consum. Stud. Home Econ. 1998, 22, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.C.; Makatouni, A. Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, O.M.; McGoldrick, P.J. Motivations of the ethical consumer. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendarwan, E. Seeing green. Glob. Comestic Ind. 2002, 170, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Teck-Chai, L. Towards socially responsible consumption: An evaluation of religiosity and money ethics. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2010, 1, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Hailes, J.; Makower, J. The Green Consumer Guide; Guild Publishing: London, UK, 1989; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, I.F. Ethics in qualitative research and evaluation. J. Soc. Work 2003, 3, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowe, R.; Williams, S. Who Are the Ethical Consumers? 2nd revised ed.; Cooperative Bank: Manchester, UK, 2001; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, W.T.; Cunningham, W.H. The socially conscious consumer. J. Mark. 1972, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.H.; Murphy, P.E.; Enis, B.M. A new approach to measuring socially responsible consumption tendencies. J. Macro Mark. 1988, 8, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, G. The self-actualizing socially conscious consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1976, 3, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecompte, A.F.; Valette-Florence, P. Mieux connaitre le consommateur socialement responsible. Décis. Mark. 2006, 41, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A. Unpacking the ethical product. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, I. Psicología Social del Consumidor; Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, R.J.; Grande, E.I. Comportamiento del Consumidor: Decisiones y Estrategia de Marketing, 8th ed.; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2013; p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Grewal, D. The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: A research agenda. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil, I. Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behavior. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B. Ethics in consumer research: An overview and prospectus. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Allen, C.T., John, D.R., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1994; Volume 21, pp. 566–571. [Google Scholar]

- Day, E.; Crask, M.R. Value assessment: The antecedent of customer satisfaction. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 2000, 13, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Martelo-Landroguez, S.; Barroso-Castro, C.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. Creating dynamic capabilities to increase customer value. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1141–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravald, A.; Grönroos, C. The value concept and relationship marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, J. Customer-perceived value in industrial contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2000, 15, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, E.; Giel, K. Customer Satisfaction Measurement and Management: Using the Voice of the Customer; Thomson Executive Press: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1995; p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Haar, J.W.; Kemp, R.G.M.; Omta, O. Creating value that cannot be copied. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means–end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J. Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring the perceived value of a service. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, K.B.; Chapman, J.D. Framing effects on buyers’ subjective product evaluations. In Advances in Consumer Research; Wallendorf, M., Anderson, P., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1987; Volume 14, pp. 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil-Saura, I.; Holbrook, M.B. Customer value in tourism services; meaning and role for a relationship marketing approach. In Strategic Marketing in Tourism Services, 1st ed.; Tsiotsou, R., Goldsmith, R.E., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2012; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, N.; Hotchkiss, J. Ciencia de los Alimentos; Acribia: Zaragoza, Spain, 1999; p. 684. [Google Scholar]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W. A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.; Briggeman, B. Food values. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Arvanitoyannis, I.; Chryssohoidis, G. Is there a real difference between conventional and organic meat? Investigating consumers’ attitudes towards both meat types as an indicator of organic meat’s market potential. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2006, 12, 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Fotopoulos, C.; Zotos, Y. Organic consumers’ profile and their willingness to pay (WTP) for selected organic food products in Greece. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2006, 19, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P. Explaining purchases of organic meat by Dutch consumers. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Choreftaki, S.; Tserkezou, P. Presentation and comments on EU legislation related to food industries-environment interactions: Sustainable development, and protection of nature and biodiversity—Genetically modified organisms. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 41, 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, A.; Moon, W.; Balasubramanian, S. Perceived risks of agro-biotechnology and organic food purchases in the United States. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2006, 37, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N.; Johnson, L.W. The role of perceived risk in the quality–value relationship: A study in a retail. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dubinsky, A. A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B. Market cues affect on consumers product evaluations. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The effects of price comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, D.; Krishnan, R.; Baker, J.; Borin, N. The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R.K.; Agarwal, S. The effects of extrinsic product cues on consumers’ perceptions of quality, sacrifice, and value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F.; Backman, S.J. An examination of the construct of perceived value for the prediction of golf travelers’ intentions to revisit. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J. Customer satisfaction, service quality and perceived value: An integrative model. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 2, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K.N.; Tellis, G.J. Contextual and temporal components of reference price. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Anleo, J.M. Consumidores Consumidos. Juventud y Cultura Consumista; Editorial Kahf: Madrid, Spian, 2014; 230p. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo JL, B.; Andrés, A.S. Cómo Mejorar el Funcionamiento de las Fuerza de Ventas, 1st ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Madrid, Spain, 2007; 184p. [Google Scholar]

- Beddington, J. Food, Energy, Water and the Climate: A Perfect Storm of Global Events? 2009. Available online: www.bis.gov.uk/assets/goscience/docs/p/perfect-storm-paper.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Brink, P.; Lehmann, M.; Kretschmer, B.; Newman, S.; Mazza, L. Environmentally harmful subsidies and biodiversity. In Paying the Polluter—Environmentally Harmful Subsidies and their Reform, 1st ed.; Oosterhuis, F., ten Brink, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Oskamp, S. Managing scarce environmental resources. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Stokols, D., Altman, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1043–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Duenas Ocampo, S.; Perdomo-Ortiz, J.; Villa Castano, L.E. El concepto de consumo socialmente responsable y su medición. Una revisión de la literatura. Estud. Gerenc. 2014, 30, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Hailes, J. The Green Consumer Guide: From Shampoo to Champagne: High-Street Shopping for a Better Environment; Gollancz: London, UK, 1989; 342p. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Barea, J.J.; Fernández-Navarro, F.; Montero-Simó, M.J.; Araque-Padilla, R. A socially responsible consumption index based on non-linear dimensionality reduction and global sensitivity analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 69, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.; Ferreira, J.M.; Raposo, M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A. Entrepreneurial intentions: Is education enough? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.-p.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.-d. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A.; Martínez-Fiestas, M.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. Neural effects of environmental advertising: An fMRI analysis of voice age and temporal framing. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínezfiestas, M.; Del Jesus, M.I.V.; Sánchezfernández, J.; Montororios, F.J. A psychophysiological approach for measuring response to messaging. J. Advert. Res. 2015, 55, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Using existential-phenomenological interviewing to explore meanings of consumption. In The Ethical Consumer; Harrison, R., Newholm, T., Shaw, D., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, M. Identifying and profiling apparel label users. In The Ethical Consumer; Harrison, R., Newholm, T., Shaw, D., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, A. Reporting analyses of covariance structures. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2000, 7, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C. A Second Generation of Multivariate Analysis: An Overview; Praeger Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1982; 392p. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, R.; Higgins, C. The partial least squares (pls) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use an illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1979; 72p. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research, 1st ed.; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New trends and patterns in sustainable consumption: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).