The Interactive Effect of Government Financial Support and Firms’ Innovative Efforts on Company Growth: A Focus on Climate-Tech SMEs in Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

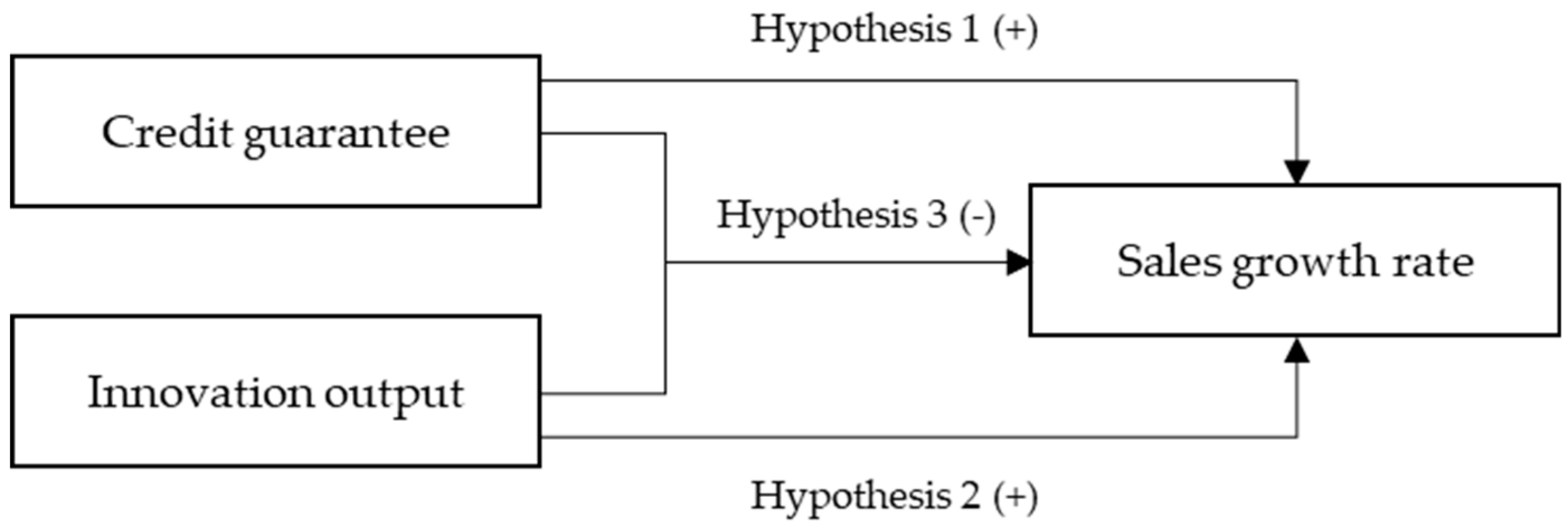

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Credit Guarantees and Firm Growth

2.2. Innovative Effort and Firm Growth

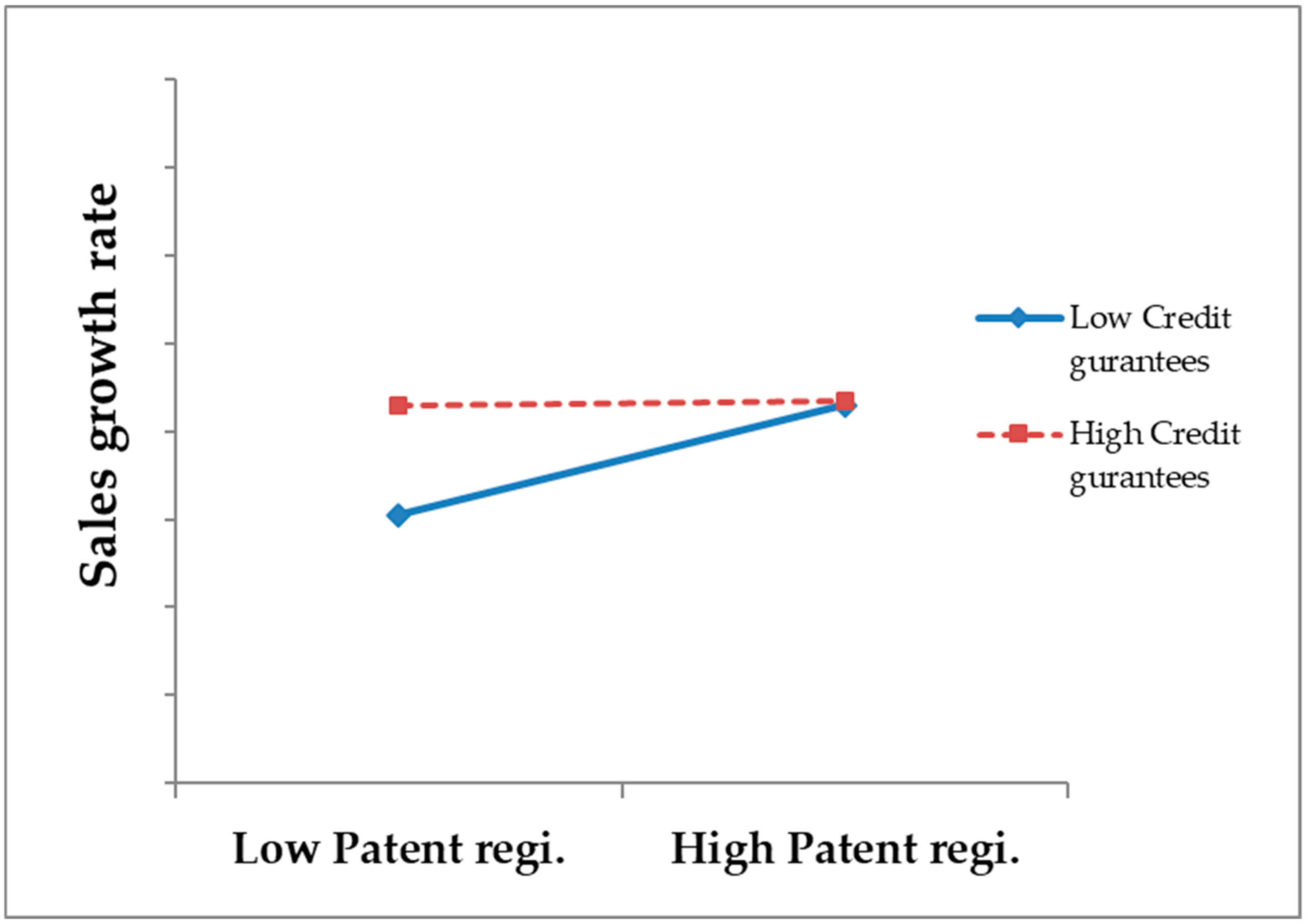

2.3. Moderating Role of Credit Guarantee

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations (UN). Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/theparis-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- The Government of the Republic of Korea. 100 Policy Tasks Five-Year Plan of the Moon Jae-in Administration. 2017. Available online: https://english1.president.go.kr/dn/5af107425ff0d (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Green Technology Center Korea. Statistics on Climate Change Industry in 2012~2018; KOR: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.H. The Financing of Innovative Firms. In Review of Economics and Institutions; University of Perugia Electronic Press: Perugia, Italy, 2010; Volume 1, Available online: http://www.rei.unipg.it/rei/article/view/4 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Belitz, H.; Lejpras, A. Financing Patterns of Innovative SMEs and the Perception of Innovation Barriers in Germany. Discussion Papers; DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–26. Available online: https://d-nb.info/1153063239/34 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Jones, R.S.; Kim, M.K. Promoting the Financing of SMEs and Start-Ups in Korea. In OECD Economics Department Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 1162, pp. 1–37. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/promoting-the-financing-of-smes-and-start-ups-in-korea_5jxx054bdlvh-en (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Beck, T.; Klapper, L.F.; Mendoza, J.C. The typology of partial credit guarantee funds around the world. J. Financ. Stab. 2010, 6, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, J.; Heshmati, A.; Choi, G.G. Effect of Credit Guarantee Policy on Survival and Performance of SMEs in the Republic of Korea. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzl, W. Is the R&D behavior of fast-growing SMEs different? Evidence from CIS III data for 16 countries. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 33, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.; Klomp, L.; Santarelli, E.; Thurik, A. Gibrat’s law: Are the services different? Rev. Ind. Organ. 2004, 24, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, T.K. The Contribution of Small Business Loan Guarantees to Economic Development. Econ. Dev. Q. 2002, 16, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, M. You can lead a firm to R&D but can you make it innovate? UK evidence from SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 565–577. [Google Scholar]

- Cannone, G.; Ughetto, E. Funding innovation at regional level: An analysis of a public policy intervention in the Piedmont region. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Building Competitive Green Industries: The Climate and Clean Technology Opportunity for Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyytinen, A.; Toivanen, O. Do financial constraints hold back innovation and growth? Evidence on the role of public policy. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1385–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noh, Y. The Role and Performance of Policy Loan on the SMEs in Korea: Firm-Level Evidence. Korean Small Bus. Rev. 2010, 32, 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.R.; Kim, S.B.; Nam, J.H. The Performance Measurement of Credit Guarantee and Methods of Improvement of Its System. Korea Rev. Appl. Econ. 2014, 16, 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage. Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gerorski, P.; Machin, S. Do Innovating Firms Outperform Non-Innovators? Bus. Strategy Rev. 1992, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griliches, Z. Patent Statistics as Economic Indicators: A Survey. J. Econ. Lit. 1990, 28, 1661–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenecker, T.; Swanson, L. Indicators of firm technological capability: Validity and performance implications. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2002, 49, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cin, B.C.; Kim, Y.J.; Vonortas, N.S. The impact of public R&D subsidy on small firm productivity: Evidence from Korean SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, H. Patent applications and subsequent changes of performance: Evidence from time-series cross-section analyses on the firm level. Res. Policy 2001, 30, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T. Firm growth, size, age and behavior in Japanese manufacturing. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Freel, M.S. Do Small Innovating Firms Outperform Non-Innovators? Small Bus. Econ. 2000, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Pucik, V. Relationship between Innovativeness, Quality, Growth, Profitability, and Market Value. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarascio, D.; Tamagni, F. Persistence of innovation and patterns of firm growth. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1493–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.H.; Yoon, B.S. The Effects of Patents on Firm Value: Venture vs. non-Venture. J. Technol. Innov. 2006, 14, 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y.; Park, H.W.; Cho, M.H. The Relationship between Technology Innovation and Firm Performance of Korean Companies based on Patent Analysis. J. Korea Technol. Innov. Soc. 2006, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.S. An Empirical Analysis about the Effect on Performance of Firm’s Patent Competency: Focusing on the High Performance Venture Firms in Korea. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2010, 11, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, E.; Zimmermann, V. The importance of equity finance for R&D activity. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 33, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolo, G.; Luzzi, A. Do liquidity constrains matter in explaining firm size and growth? Some evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2006, 15, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colombo, M.; Grilli, L. Funding gaps? Access to bank loans by high-tech startups. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, A. The effect of credit guarantees on SMEs’ R&D investments in Korea, Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2015, 23, 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, P.M.; Serrasqueiro, Z.; Leitao, J. Is there a linear relationship between R&D intensity and growth? Empirical evidence of non-high-tech vs. high-tech SMEs. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, M. Quantile estimates of the impact of R&D intensity on firm performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 39, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseka, M.M.; Ramos, C.G.; Tian, G.L. The Most Appropriate Sustainable Growth Rate Model for Managers and Researchers. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Shim, D.; Lee, D. Evaluation of complementarity effect of innovation policies: Venture certification and Inno-biz certification in Korea. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2020, 65, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, R.; Olsen, C.; Devore, J.L. Introduction to Statistics and Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Path Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brault, J.; Signore, S. The Real Effects of EU Loan Guarantee Schemes for SMEs: A Pan-European Assessment; EIF Working Paper, No. 2019/56; European Investment Fund (EIF): Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elston, J.; Audretsch, D. Financing the entrepreneurial decision: An empirical approach using experimental data on risk attitudes. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 36, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, D. SME policies as a barrier to growth of SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 1067–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Dvoulety, O.; Cadil, J.; Mirošník, K. Do Firms Supported by Credit Guarantee Schemes Report Better Financial Results 2 Years After the End of Intervention? BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2019, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description/Measure |

|---|---|

| Sales growth rate | (Annual sales in 2016 − annual sales in 2012)/annual sales in 2012; % |

| Patent registration | The number of patents registered by the company between 2012 and 2016 |

| Credit guarantee | The amount of the credit guarantees from KOTEC; Korean won |

| Inno-Biz | Certified as an Inno-Biz company between 2012 and 2016; dummy (yes = 1) |

| Company age | The number of years the firm has been in existence from its foundation to 2016 |

| Asset growth rate | (Total assets in 2016 − total assets in 2012)/total assets in 2012; % |

| OP growth rate | (OPs in 2016 − OPs in 2012)/OPs in 2012; % |

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales growth rate | 6.41 | 17.04 | −71.55 | 128.86 |

| Patent registration | 9.9 | 15.12 | 0 | 153 |

| Credit guarantees | 1,376,008,326 | 2,492,226,992 | 0 | 23,860,000,000 |

| Inno-Biz | 0.55 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Company age | 15.66 | 9.16 | 0 | 60 |

| Asset growth rate | 13.12 | 17.04 | −32.49 | 130.51 |

| OP growth rate | 10.26 | 39.50 | −81.32 | 395.93 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sales growth rate | 1 | |||||

| 2. Patent registration | 0.102 * | 1 | ||||

| 3. Credit guarantees | 0.099 * | 0.023 | 1 | |||

| 4. Inno-Biz | 0.045 | 0.114 ** | 0.430 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Company age | −0.176 ** | 0.061 | 0.036 | 0.236 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Asset growth rate | 0.600 ** | 0.037 | 0.048 | 0.025 | −0.161 ** | 1 |

| 7. OP growth rate | 0.537 ** | 0.025 | 0.041 | 0.015 | −0.079 | 0.411 ** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SD | β | SD | β | SD | |

| Inno-Biz | 0.050 | 0.063 | 0.016 | 0.070 | 0.020 | 0.070 |

| Company age | −090 *** | 0.027 | −0.089 *** | 0.027 | −0.087 *** | 0.027 |

| Asset growth rate | 0.441 *** | 0.029 | 0.437 *** | 0.029 | 0.437 *** | 0.029 |

| OP growth rate | 0.348 *** | 0.018 | 0.346 *** | 0.018 | 0.348 *** | 0.018 |

| Credit guarantees (CG) | 0.059 * | 0.003 | 0.058 * | 0.003 | ||

| Patent registration (PR) | 0.080 *** | 0.030 | 0.080 *** | 0.030 | ||

| CG × PR | - | - | −0.060 ** | 0.003 | ||

| F-value | 1270.66 *** | 870.87 *** | 760.27 *** | |||

| R2 | 0.469 | 0.478 | 0.482 | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.009 | 0.004 | ||||

| Credit Guarantees | B | SE | t-Value | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 SD | 0.159 | 0.050 | 30.16 ** | 0.060 | 0.258 |

| Mean | 0.041 | 0.035 | 10.18 | −0.028 | 0.110 |

| +1 SD | 0.029 | 0.039 | 0.73 | −0.048 | 0.105 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Yeom, S.; Ko, M.C. The Interactive Effect of Government Financial Support and Firms’ Innovative Efforts on Company Growth: A Focus on Climate-Tech SMEs in Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229666

Kim D, Yeom S, Ko MC. The Interactive Effect of Government Financial Support and Firms’ Innovative Efforts on Company Growth: A Focus on Climate-Tech SMEs in Korea. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229666

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, DaEun, Sungchan Yeom, and Myeong Chul Ko. 2020. "The Interactive Effect of Government Financial Support and Firms’ Innovative Efforts on Company Growth: A Focus on Climate-Tech SMEs in Korea" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229666

APA StyleKim, D., Yeom, S., & Ko, M. C. (2020). The Interactive Effect of Government Financial Support and Firms’ Innovative Efforts on Company Growth: A Focus on Climate-Tech SMEs in Korea. Sustainability, 12(22), 9666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229666