1. Introduction

Today, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a legitimate framework to guide the daily activities of businesses and society. The SDGs highlight the need to change the unsustainable path pursued up to now [

1] and to address the main economic, social, and environmental challenges. Entrepreneurial activity may play a significant role in this change [

2,

3] by contributing to the three pillars of SDGs, namely, economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental protection.

Entrepreneurial action shapes the economic, social, and environmental context of a country. In fact, entrepreneurs create the change that incumbent firms fail to perform due to organisational inertia or the risk of cannibalising existing business models [

4]. For this reason, entrepreneurship is usually associated with economic growth [

5]. Nonetheless, the effects of entrepreneurship differ according to the type of activity, and in some cases, entrepreneurship only generates turbulence and deploys resources [

6,

7].

Different motivations exist for undertaking an entrepreneurial venture. Some studies distinguish between opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship activities: Positive factors, such as opportunities to socially develop or simply the desire to be independent; and negative motivations, such as unemployment or the general dissatisfaction with the current situation [

8]. Other studies distinguish between innovative and non-innovative entrepreneurial activities and find that their effect on economic performance is different [

9]. As the motivation to start a new venture affects its performance [

8], the understanding of which type of entrepreneurial activity supports the transition towards sustainable development is of special interest [

2].

Despite the increase in the sustainability-related entrepreneurship literature, the number of studies is still lacking, and those that exist remain mostly conceptual. The limited research on the role of start-ups in achieving SDGs is unfortunate, especially as the UN has identified entrepreneurship, together with innovation, as being key elements in addressing sustainable development challenges [

10]. Therefore, a need exists for studies that empirically investigate the outcomes of entrepreneurship for sustainable development.

Our paper aims to fill this gap by exploring the relationship between the type of entrepreneurship and sustainability, contributing to the development of the theory of this phenomenon. We investigate whether and under what circumstances entrepreneurship can contribute to the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of SDGs. One of novelties of this study is that attention is devoted to evaluating the effect of the different types of entrepreneurial activity on SDGs. This study focuses on two classifications which have gained importance in classifying entrepreneurial motives; namely, opportunity versus necessity entrepreneurship [

11] and innovative versus non-innovative entrepreneurship [

12]. We also evaluate the role of foreign direct investment (FDI) in mediating the relation between the different types of entrepreneurial activity and SDGs. FDI plays a key role in financing the achievement of SDGs [

13] and consequently, together with entrepreneurship, can contribute to achieving these goals. Additionally, our study contains countries under different economic conditions, which allow us to study the interactions of entrepreneurship with SDGs in different contexts.

Our research provides evidence that the type of entrepreneurship influences the achievement of the global index scores of SDGs, and that FDI may act as a moderator in these relations.

This study contributes to the sustainable development literature by attempting to respond to the call for a better understanding of the role of entrepreneurship in achieving SDGs. Hall, Daneke, and Lenox (2010) [

14] find that although the UN recognizes entrepreneurship as an important driver of sustainable development, there is little knowledge about under what conditions entrepreneurs can simultaneously foster economic growth, advance environmental goals, and improve social conditions. Our study also contributes new insights to decision-makers for developing policies to support the achievement of SDGs. A better understanding of the conditions under which entrepreneurship can contribute to sustainable development is needed to enact better policies accordingly.

The paper is organised as follows: In the next section, we review the relevant literature.

Section 3 presents the data, and in

Section 4 we explain the empirical method.

Section 5 presents the empirical results.

Section 6 gives the conclusion and a discussion of the main results.

2. The Contribution of Entrepreneurship to the Sustainable Development

Entrepreneurship influences the achievement of SDGs in its three pillars: Economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental protection. Sustainable entrepreneurship intends to balance these three dimensions simultaneously, linking business and sustainable development [

15,

16]. Due to the difficulties inherent in trying to achieve these objectives simultaneously, sustainable entrepreneurship is a more complex phenomenon than entrepreneurship driven only by economic incentives [

16].

Recently, researchers have applied the theory of planned behaviour [

17] to explain intention formation in sustainable entrepreneurship [

16,

18]. According with this theory, an individual’s attitudes, motivations, and beliefs together shape said individual’s behaviours. Forming a new firm is usually triggered by profit expectations [

19] or by the difference between expected profits and current wages [

20,

21]. However, certain individuals are reconsidering this economic motivation to strike a balance between the environment and society [

22].

New ventures typically address the economic prosperity dimension, as they are considered as drivers of economic growth, employment generation, and technological upgrading [

23,

24]. New ventures exploit opportunities usually not well-understood by incumbent firms [

25,

26] that are displaced in a process of “creative destruction” [

12]. Individual’s beliefs can help them to uncover new sustainable opportunities and address the social and environmental dimensions of the SDGs. Therefore, entrepreneurs can change the business environment by redesigning industries toward a sustainable path [

26,

27,

28].

Entrepreneurship contributes to most of the individual SDGs [

15]. In fact, entrepreneurship has a strong direct engagement with industry, innovation, and infrastructure (SDG 9); good health and well-being (SGD 3); responsible consumption and production (SGD 12) [

29]; and economic development (SGD 8) [

3]. Other SDGs are addressed either indirectly, or in an aggregated term. For instance, new ventures can indirectly influence the following: Causes of poverty (SDG1), a lack of education (SDG 4), affordable energy (SDG 7), and climate action (SDG 13) [

3,

29]. For example, Cohen and Winn (2007) [

26] show that market failures contributed to environmental degradation, but also provided opportunities to entrepreneurs to introduce new business models. Nevertheless, some goals are less suitable for entrepreneurial contributions than others; for example, SDG 17 (partnership for the goals) and SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), because the underlining indicators depend largely on governmental action [

29]. Nonetheless, Pacheco, Dean, and Payne (2010) [

30] argue that entrepreneurs can also influence their institutional context. However, importantly, entrepreneurial activities for sustainable development may run the risk of achieving one goal at the expense of another one. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the effects of entrepreneurial activity globally and per goal.

However, many new ventures might not be agents of change with regards to sustainability, and some might actually create negative effects. Unsustainable businesses that are triggered by profit expectations [

19] usually misuse resources, negatively affecting the environment [

31,

32]. In many industries, start-ups can simply originate “turbulence” [

6,

7]. Marginal start-ups with a low likelihood of survival displace incumbent firms and other marginal start-ups. These “revolving door” start-ups are continuously entering and exiting the market destroying jobs and deploying resources that could be used more efficiently by other firms. This situation is even more pronounced in countries with weak institutions, which incentivises unproductive entrepreneurship [

33].

Empirically, few studies have examined whether and how entrepreneurship can foster sustainable development. The literature finds that entrepreneurship does not contribute positively to all dimensions of sustainable development. Indeed, Youssef et al. (2018) [

32] and Dhahri and Omri (2018) [

34] find that entrepreneurship does not contribute to the environmental dimension goal. According to Youssef et al. (2018) [

32], formal and informal entrepreneurships increase pollution, particularly in low-income countries [

35]. In high-income countries, [

35] finds an inverted U-shaped relation between entrepreneurship and pollution. On a positive note, [

34] suggest that entrepreneurship positively contributes to economic and social dimensions, and Pansera and Sarkar (2016) [

36] argue that resource-scarce entrepreneurs derive the maximum value from limited resources contributing positively to the achievement of SDGs.

To sum up, as entrepreneurship can positively and negatively influence the achievement of SDGs, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1. Entrepreneurship is likely to influence the achievement of SDGs.

The prevalence of the effect depends on the type of entrepreneurial activity. Indeed, not every kind of entrepreneurship has the same impact in the economy and society. Entrepreneurship is rather heterogeneous and complex, in which innovative and opportunity entrepreneurs occur along with non-innovators and escapees from unemployment [

37]. Accordingly, new firm creation is not necessarily associated with economic growth and innovation, particularly in less-developed countries. The positive relation between economic growth and entrepreneurial activity only occurs when “opportunity entrepreneurs” (those motivated by market opportunities) are separate from “necessity entrepreneurs” (those motivated by a lack of opportunities in the labour market) [

38]. Indeed, opportunity entrepreneurs take advantage of market opportunities and introduce new products, services, or processes [

39], and can also tackle sustainable opportunities. Fostering opportunity entrepreneurship leads to economic growth [

40] and job creation in both developed and developing economies [

41]. Opportunity entrepreneurship reflects the creation of knowledge and technology, which in the end positively affects economic growth and social development. Therefore, countries with a higher level of opportunity entrepreneurship achieve faster growth and higher economic prosperity. In developing countries, where inequalities are more pronounced, opportunity entrepreneurship increases employment and economic growth, while reducing inequalities. In addition, opportunity entrepreneurs might see sustainable opportunities (in production efficiency, energy, and education, for example) as being a competitive advantage [

14]. In fact, Shepherd and Patzelt (2011) [

15] and York and Venkataraman (2010) [

42] argue that entrepreneurship can be a solution to the environmental challenges by contributing to their preservation and biodiversity. However, balancing the desire to make profits with maintaining economic efficiency and environmental protection is not simple [

43]. Entrepreneurs often emphasise individual rewards over sustainability goals by adopting behaviours that are harmful to the environment [

34].

In contrast, entrepreneurs who start their businesses out of necessity due to the lack of alternative employment opportunities have different characteristics [

44]. For example, they have inferior human capital endowments (in terms of formal education and relevant experiences) that negatively affect start-ups’ performance and economic growth [

45]. As necessity entrepreneurship is replaced by opportunity entrepreneurship, the level of economic development increases [

46]. Because necessity entrepreneurs are pushed into entrepreneurship, they usually have less time and fewer resources in terms of capital and knowledge [

47,

48]. Thereby, while opportunity entrepreneurship usually involves attempts to exploit new market opportunities, necessity entrepreneurship is more likely to be imitative ventures. Additionally, necessity and informal entrepreneurships make a higher contribution to environment pollution in comparison to opportunity and formal entrepreneurships [

49].

To sum up, opportunity entrepreneurs are positively associated with economic prosperity and social equity, and contribute significantly to job creation, product innovation, and the exploitation of sustainable business opportunities. In contrast, necessity entrepreneurship can negatively affect the achievement of SDGs, because of their lower contribution to economic growth and social equity and their higher contribution to pollution. Therefore, we posit that:

Hypothesis 2a. Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is likely to positively influence the achievement of SDGs.

Hypothesis 2b. Necessity-driven entrepreneurship is likely to negatively influence the achievement of SDGs.

By the same token, a new firm may not necessarily lead to a technological upgrade or industrial growth [

50,

51]. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between innovative entrepreneurs, (those who introduce product innovations, new processes, and new forms of organisations) and non-innovative entrepreneurs [

12,

52]. Further, Baumol (2005) [

53] argues that most of the new firm entries are due to imitators or replicators, and that only a tiny minority are due to innovators.

Innovative and high growth entrepreneurs, also known as Schumpeterian entrepreneurs, positively affect economic growth [

54]. These innovative entrepreneurs are distinguished by their ability to search for and create new market opportunities [

55]. Their academic education allows them to develop knowledge-based technology or research-driven opportunities [

56]. Innovative entrepreneurs thereby convert advances in knowledge into economic growth. In addition, innovative entrepreneurship can be a source of societal progress by reducing inequalities [

57]. Nonetheless, the definition of innovative entrepreneurship highlights that these entrepreneurs temporarily take advantage of a monopoly position. In terms of environmental sustainability, Youssef et al. (2018) [

32] argue that certain conditions have to be met to ensure the positive effect of entrepreneurship. Among these conditions, the authors show that the innovation when combined with entrepreneurship improves the quality of the environment.

Like necessity entrepreneurship, non-innovative entrepreneurship is less likely to foster economic growth and job creation. These entrepreneurs do not have the ability to introduce new production methods, such as technological products or services or even a new organisational form, because, in effect, they replicate previous ventures and mainly create “turbulence” in the market [

6,

7].

To sum up, innovative entrepreneurs positively contribute to the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of the SDGs; and non-innovative entrepreneurs make less of a contribution to economic growth and social equity. Therefore, we posit:

Hypothesis 3a. Innovative entrepreneurship is likely to positively influence the achievement of SDGs.

Hypothesis 3b. Non-innovative entrepreneurship is likely to negatively influence the achievement of SDGs.

3. The Role of FDI on the Relationship between the Type of Entrepreneurship and the Sustainable Development

Some studies provide conflicting evidence regarding the relation between FDI and entrepreneurship [

58]. While Doytch and Epperson (2012) [

59] find that FDI positively affects entrepreneurship, De Backer and Sleuwaegen (2003) [

60] find that FDI discourages entry and even stimulates the exit of domestic entrepreneurs. On one hand, FDI can stimulate local entrepreneurship by reinforcing cooperation between foreign investors and host firms [

61]. This cooperation contributes to the development of new products and new technology by diffusing knowledge and managerial practices [

62]. These contributions help to create new markets and entrepreneurial opportunities that provide access to critical resources, such as financial capital [

63]. FDI can also boost export competitiveness by bringing technical and knowledge externalities [

64]. However, foreign investors can increase competition for local entrepreneurs that crowds out possible entrants and raises the barriers to entry, as foreign competitors are usually more technologically advanced and can better exploit economies of scale [

65]. The prevalence of the effect depends on the structure of FDI inflows (inward versus outward FDI), types of entrepreneurship, and the technological gap or institutional support of the host country [

65]. For example, Kim and Li (2014) [

66] provide evidence that the positive impact of FDI on firm formation is most relevant in countries which are characterised by weak institutional support, particularly in the less-developed countries.

Turning now to the type of entrepreneurial activity, Albulescuab and Tămăşilă (2014) [

65] conclude that the effect of FDI on the entrepreneurship depends on the motivations to start a new venture. FDI has a positive effect on opportunity entrepreneurs, as it leads to uncovering untapped market opportunities. Entrepreneurial activity can increase as multinational firms enter the market due to the demand effect. With regards to necessity entrepreneurs, while inward FDI does not influence this type of entrepreneurship, outward FDI can positively influence it. When capital leaves the country, it has a negative effect on job creation that stimulates the necessity of entrepreneurial activity.

Although the empirical literature presents mixed results regarding knowledge spill overs from FDI [

67], the majority of empirical studies conclude that inward FDI has a positive influence on local innovative activities [

68]. Using a large firm-level sample, Gorodnichenco, Svejanar, and Terrell (2020) [

69] show that FDI has a positive spill over effect on product and technology innovations by domestic firms.

FDI influences entrepreneurship according to the motivations which underlie its activity, and in turn, entrepreneurship has an effect on sustainable development. Thus, we consider that it is relevant to assess the moderating effect that FDI might have between the type of entrepreneurship and the achievement of SDGs.

FDI plays a key role in providing access to capital and knowledge [

64,

68], and therefore foreign investors might reinforce the positive effect of opportunity and innovative entrepreneurship on SDGs. FDI can also reinforce the positive effect of entrepreneurship on the economic and social dimensions of SDGs. Furthermore, FDI brings about technical and informational externalities and promotes economic growth and fosters job creation. In addition, FDI can encourage new firms to develop new products due to increased demand in the host country [

70].

FDI can offset the negative effect between necessity-driven entrepreneurs who have fewer capital- or knowledge-based resources available [

47,

48] and non-innovative entrepreneurs who are characterised by a lack of innovative products and services and the achievement of SDGs. Moreover, FDI can encourage knowledge diffusion and improve the managerial skills of both. This diffusion can occur directly when workers employed in foreign-owned firms transition to entrepreneurship. Additionally, both necessity and non-innovative entrepreneurs can offer comparable products by imitating their foreign competitors, while leveraging their local knowledge. With this knowledge, non-innovative entrepreneurs can more easily identify new markets, as they are comparatively more difficult and costly for foreign competitors to identify [

70]. Overall, together with necessity entrepreneurship, FDI is likely to positively influence economic and social dimensions. Thus, we state the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a. FDI is likely to reinforce the positive effect between opportunity-driven and innovative entrepreneurship and the achievement of SDGs.

Hypothesis 4b. FDI is likely to reduce the negative effect between necessity and non-innovative entrepreneurship and the achievement of SDGs.

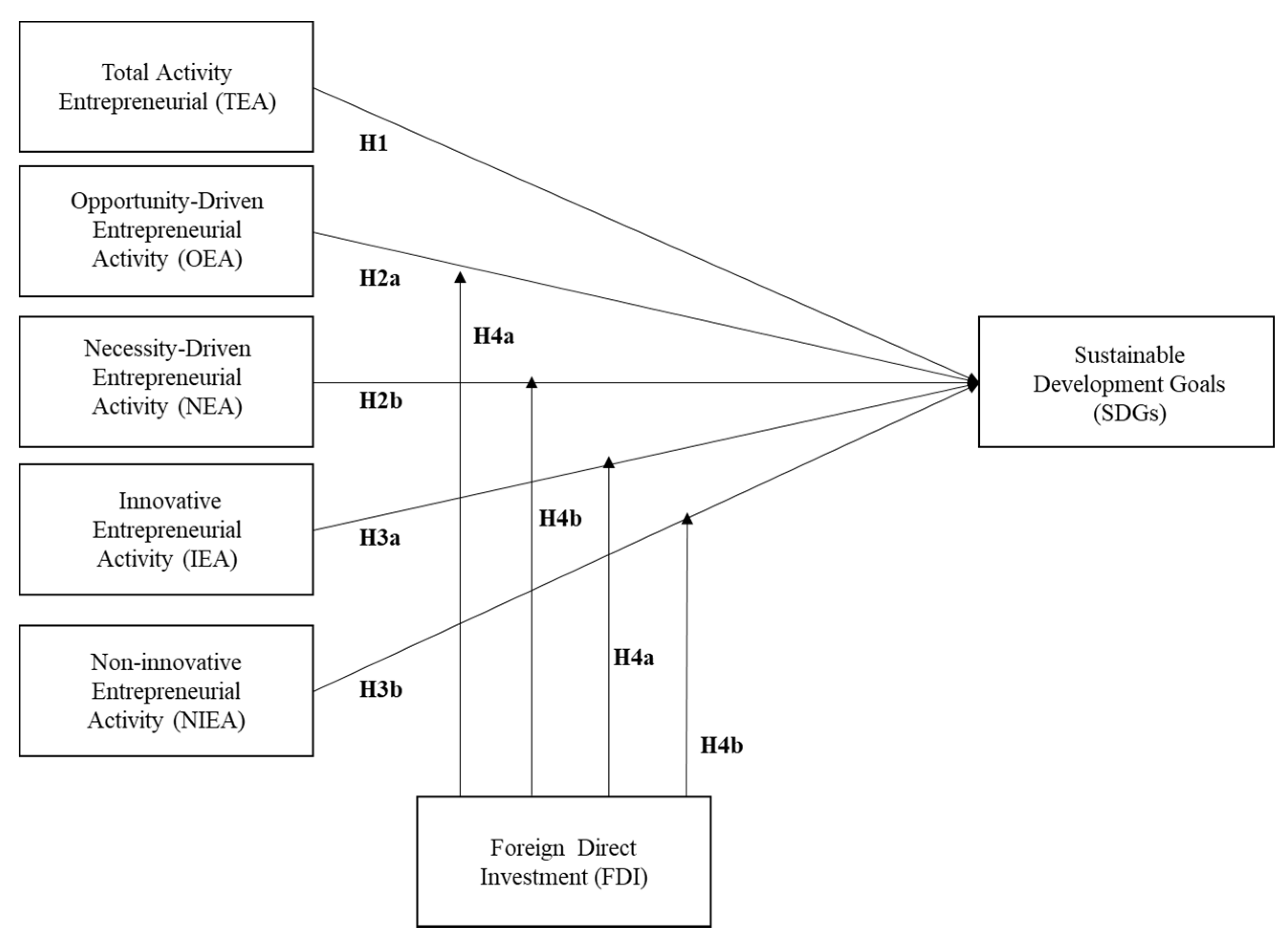

Figure 1 shows the proposed model, including the hypothesised relationships. In this model, FDI has a moderating role between entrepreneurial activity and the achievement of SDGs.

5. Research Design

To investigate whether entrepreneurial activity contributes to the achievement of SDGs, we first estimate the following model:

in which

i refers to the country.

The dependent variable is the SDG Index, which tracks country performance on the 17 SDGs for the year 2019. All goals are equally weighted in this index [

71].

Our variable of interest is total entrepreneurial activity (TEA), measured as the percentage of the adult population (aged 18–64) which is actively involved in entrepreneurial start-up activity averaged between 2015 and 2018. According to our first hypothesis, we postulate that entrepreneurial activity is likely to affect the achievement of SDGs, however, the direction of the effect depends on the type of entrepreneurial activity.

To test the predictions that necessity entrepreneurship negatively affects the achievement of SDGs and that opportunity entrepreneurship positively affects the achievement of SDGs, we re-estimate Equation (1) by splitting the TEA by necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship activities. NEA is the proportion of total entrepreneurial activity, which reports no better options for work averaged between 2015 and 2018. In contrast, OEA is the average proportion of total entrepreneurial activity in which the main driver for being involved in entrepreneurship is to be independent or increase income.

Additionally, we also distinguish between innovative and non-innovative entrepreneurships. IEA is the average proportion of total entrepreneurial activity which offers new products or services to some, or all customers, which is offered by few or no other competitors. We predict that IEA is positively related to sustainable development, while NIEA is negatively related.

Finally, we also evaluate the direct and indirect effects of FDI on the achievement of SDGs. FDI is the net new investment inflows less disinvestment from foreign investors that is divided by GDP [

73].

Several control variables, which are included in the X vector, reflect key trends which could affect SDGs. In all countries, the transformation of SDGs requires a huge increase in public and private investment [

13] and therefore, government expenditure, GOVEXP, plays a fundamental role in the achievement of SDGs. GOVEXP is the sum of the general government’s final consumption and military, health, and education expenditures as a percentage of GDP. We also control for population, POP, which is measured as the natural logarithm of the population for each country. The variable of interest and control variables are averaged over the period from 2015 to 2018. By computing the average of the variables, we eliminate the short-to-medium term effects [

74]. In addition, we include country income group (INCOMRG) fixed effects in order to control for countries’ economic conditions.

6. Results

Table 3 presents the OLS regression results for Equation (1). Model (1) evaluates the effect of TEA, while Models (2) and (3) analyse the influence of OEA and NEA, and IEA and NIEA, respectively.

Model (1) shows that TEA has a negative effect on the achievement of SDGs. The coefficient is negative and is statistically significant at the 1% level. Model (2) presents the results for NEA and OEA. We find that the coefficient for NEA is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. In Model (3), we divide the TEA into the IEA and NIEA. The results show that the coefficient associated with NIEA is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Our results are in line with Hypotheses 2b and 3b. The influence of entrepreneurial activity on SDGs is negative when entrepreneurs are pushed to entrepreneurship due to the lack of job opportunities or create non-innovative businesses. In all the models, the coefficient associated with FDI is not statistically significant.

Regarding the control variables, we find that they are all consistent with the literature. GOVEXP is fundamental in mobilising capital and finance activities which could enhance sustainable development and the achievement of SDGs [

75]. In all models, the coefficient for GOVEXP is statistically significant at the 5 or 10% level.

Next, we evaluate the influence of entrepreneurship on the main SDGs. For this purpose, we classify the SDGs according to Sachs et al.’s (2019) [

71] classifications: People, prosperity, planet, peace, and partnership. Each category goal score is computed as being the sum of each goal score, divided by the total number of goals. We therefore re-estimate the previous regressions by using five dependent variables. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 4. Panels A, B, and C present the results for Models (1), (2), and (3) of

Table 3, respectively.

Entrepreneurship negatively and significantly affects the following SDG dimensions: People, posterity, and partnership. For the planet and peace goals, the effect is also negative, but not statistically significant (Panel A of

Table 4).

Similarly, NEA negatively and significantly affects the people and prosperity goals (Panel B of

Table 4). Both coefficients are statistically significant, although the negative effect is larger for the people goal. Surprisingly, we do not find a significant and negative effect of NEA on the planet goal, as expected in the literature. For OEA, we find a negative and significant effect on the propensity dimension which suggests that opportunity-based start-ups can cause turbulence and therefore negatively affect economic growth. However, we do find a negative and significant effect on the partnership goal for both OEA and NEA. Although this goal depends primarily on the government, entrepreneurs can influence their institutional context.

By the same token, NIEA also negatively affects the partnership goal. Additionally, it negatively contributes to the achievement of the people and prosperity goals (Panel C of

Table 4). Again, the negative effect is larger for the people goal, and we continue to not find any effect on the planet and peace goals. Surprisingly, IEA does not seem to have an effect on the goal of innovation. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that the targets of goal 9 (industry, innovation, infrastructure) are mainly related to sustainable infrastructure and industrialisation, to an upgrade in the technological capabilities of industrial sectors, and an increase in access to information and communications technology. Considering that our sample of entrepreneurs includes mainly start-ups established in the retail sector, the effect on sustainable infrastructure and industrialisation is expected to be low.

Table 5 presents the results for the moderating role of FDI on the relation between entrepreneurial activities and the achievement of SDGs. For that purpose, we add several interaction terms between the variable FDI and the different types of TEA described above to Equation (1). Again, Model (1) gives the results for TEA, while Models (2) and (3) display the results for OEA and NEA, and IEA and NIEA, respectively. Due to its importance on raising capital and knowledge diffusion, FDI should positively affect the relation between entrepreneurship activities and the achievement of SDGs.

In Model (1), TEA continues to negatively affect the achievement of SDGs. Nevertheless, we find that the coefficient for the interaction term between FDI and TEA is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level, which means that in countries with a higher share of FDI, entrepreneurial activity promotes sustainable development. The same occurs with NEA. While the coefficient associated with NEA is negative, the coefficient for the interaction between FDI and NEA is positive, which indicates that FDI can motivate entrepreneurs to establish sustainable businesses when they have no alternative occupations. FDI could provide access to knowledge and capital. For NIEA, we continue to find a negative effect on sustainable development, although the interaction term between NIEA and FDI is positive, albeit non-significant. Thereby, we find partial support for Hypothesis 4b. We continue to find no significant effects for OEA and IEA on their interaction terms with FDI.

Table 6 shows the results for the interaction effects between FDI and entrepreneurship on the five SDG dimensions. Panels A, B, and C present the results for Models (1), (2), and (3) of

Table 3, respectively.

In Panel A, we find that entrepreneurship continues to negatively affect the achievement of SDGs in the people, prosperity, and partnership dimensions. Nevertheless, the interaction effect between entrepreneurship and FDI is positive and significant for the people goal, which indicates that countries with more FDI and entrepreneurial activity are more likely to achieve the people index score. However, the total effect of entrepreneurship on the people goal is still negative.

In Panel B, we divide entrepreneurship into NEA and OEA. NEA continues to negatively affect the achievement of people, prosperity, and partnership goals. Nevertheless, the interaction effect between NEA and FDI is positive and is statistically significant for the people and partnership goals. Although the total effect of NEA is still negative, the countries with more FDI and NEA are more likely to improve their SDGs in terms of the people and partnership dimensions. Moreover, FDI has a positive effect on the partnership goal, which means that foreign investors can create valuable networks by building inter- and intra-industry alliances or partnerships to improve countries’ sustainability. Contrary to our expectation, the interaction effect between OEA and FDI is negative for the prosperity and partnership dimensions. This finding could be due to the fact that opportunity entrepreneurs want to take advantage of market opportunities and are reluctant to collaborate with foreign investors who could be responsible for the crowding effect that has a negative effect on economic growth and sustainable development [

76]. In fact, foreign competitors crowd out entrepreneurial activity by absorbing potential entrepreneurs as employees [

77].

By the same token, in Panel C, we find that NIEA negatively affects the achievement of the people, prosperity, and partnership goals. Like NEA, the interaction effect between FDI and OEA is positive for the people dimension. This result indicates that there is a positive spill over effect of FDI regarding ending poverty and enhancing the contribution of entrepreneurship for basic needs, such as nutrition, education, and access to water, sanitation, and electricity.

Although our study is explorative by nature, it is important to address an important issue, the endogeneity of the entrepreneurship variables. We estimated Equation (1) using OLS, however, there is a potential bi-directional relationship between entrepreneurship and sustainability. Entrepreneurship may influence SDGs, but SDGs may also have an impact on entrepreneurship. For example, SDGs may inspire entrepreneurs to launch new ventures with sustainable business models or products, which translates to more entrepreneurial activity. To account for this issue, in our previous analyses, we used the lagged proportion of individuals engaged in entrepreneurial activity averaged over the period 2015–2018 to explain the SDGs score achievement in 2019. Furthermore, we employ an instrumental variable (IV) approach. To instrument for the entrepreneurship variables, we used their lagged values averaged over the period 2012–2014. The reasoning is that the past prevalence of entrepreneurial activity in a country motivates potential entrepreneurs to move into entrepreneurship, but the past level of entrepreneurial activity is unlikely to account for the current SDGs´ score. Entrepreneurship has only begun to gain ground as a concept to promote the three pillars of sustainable development after 2014 [

1].

Table 7 presents the IV regression results for TEA, OEA, and NEA, and IEA and NIEA, respectively, in Models (1), (2), and (3).

Table 8 presents the results for the moderating role of FDI on the relation between entrepreneurial activities and the achievement of SDGs using IV approach.

Table 7 and

Table 8 show that our IV results are very similar to previous findings using OLS estimation. As shown previously, entrepreneurship contributes negatively to the achievement of SDGs, and FDI helps to diminish this negative effect, as it improves the relation between NEA and NIEA and SDGs´ achievement. The only difference in IV estimation is that the negative impact of NEA is not statistically significant in Model (2) of

Table 7. This might be due to the substantial reduction in the number of observations (55 observations in IV vs. 67 observations in OLS). However, when we include the interaction effect between NEA and FDI, the coefficient associated with NEA becomes negative and statistically significant (see Model (2) of

Table 8). The IV results for the five dimensions of the SDGs also maintain the same. The results are available by request.

For an instrument to be valid, the following conditions have to be satisfied. First, the instruments need to be correlated with the endogenous variables. In

Appendix B,

Table A8, we see that this condition is satisfied. Second, the lagged values of entrepreneurial activity should not be strongly correlated with the sustainability score in 2019, otherwise the estimated coefficient would still be biased. To test the relevancy of the instrument, we report the Kleibergen-Paap (2016) [

78] wald F statistics. The results are reported on the bottom of

Table 7 and

Table 8. The rejection of the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistics indicates the validity of the instruments used.

At this point, we have to address one shortcoming of OLS and IV regressions: These estimations provide only mean estimates and consequently they are unable to capture the full conditional distribution of SDGs scores. Additionally, the test for normality based on skewness and kurtosis rejected that the residuals from OLS estimation were normal distributed. Non-normal errors can be problematic in smaller samples. To account for this issue, we employ Quantile Regression (QR). QR provides more information on the relationship between SDG scores and entrepreneurship as it estimates the coefficients in any point of the conditional distribution of the SDG scores. Furthermore, it does not require a no-distribution assumption and it is more robust to non-normal errors.

Models (1), (2), and (3) in

Table 9 present the QR estimates of Equation (1) evaluated at the 25th, 50th, 75th percentile, respectively.

Interestingly the negative marginal effect of TEA, NEA, and NIEA is only statistically significant for those countries that have a relatively lower SDG score. The marginal effect of TEA, NEA, and NIEA is not statistically significant for those countries that have achieved a higher SDGs score.

In

Table 10, we present the results for the moderating role of FDI on the relation between entrepreneurship and the achievement of SDGs using QR estimation approach. Again, Models (1), (2), and (3) provides the estimates at the 25th, 50th, 75th percentile, respectively.

Like in the previous table, the negative marginal effect of TEA, NTEA, and NIEA is statistically significant for those countries that have a SDG score below the 50th percentile. Although we find positive coefficients for the interaction effects between FDI and TEA, NTEA, and NIE, these coefficients are not statistically significant. Overall, these results support Hypotheses 2b and 3b, while providing further understanding of the role of entrepreneurship across the SDGs score distribution. These results can be justified by the fact that the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth depends on the level of economic development of a country [

41]. Descriptive statistics show that lower SDGs´ scores are registered in lower income countries. Thus, in relatively poor countries, where inequalities are more pronounced, necessity entrepreneurship may be more frequent with a negative effect on economic growth, contributing negatively to the achievement of SDGs.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Research on entrepreneurship and sustainable development has experienced some progress over the last few years. However, the actual outcomes of entrepreneurship on sustainable development are largely unknown. We investigate the effects of entrepreneurship and its different types on the achievement of SDGs in a sample of 67 developed and developing countries. Additionally, as FDI plays a fundamental role in external finance for sustainable development [

10] and leads entrepreneurial ventures towards SDGs, we also investigate the moderating role of FDI on the relation between entrepreneurship and sustainable development.

Although entrepreneurship is viewed as being a source of economic growth and employment creation [

79], we conclude that entrepreneurship has an overall negative effect on the achievement of SDGs that harms sustainable development, particularly for countries with lower SDGs scores. Nevertheless, we observe that this negative effect is mainly due to necessity and non-innovative entrepreneurship. When entrepreneurs are motivated to start a new business by necessity, the influence of entrepreneurship on sustainable development is negative, because they have no other alternative occupations, or they introduce products or services which are very similar to those offered by other competitors. Thereby, they have a marginal contribution to economic prosperity dimension of the SDGs. When we disaggregate the results by the five dimensions goals of people, prosperity, planet, peace, and partnership, the negative effect is evident in the people and prosperity goals, while no type of entrepreneurship has any effect on the planet goals. Nevertheless, FDI helps diminish the negative effect of entrepreneurship and the achievement of SDGs, as it improves the relation between total and necessity entrepreneurships and the achievement of SDGs. This influence is particularly significant with regards to the goals of ending poverty and increasing basic needs, such as nutrition, education, access to water, sanitation, and electricity. These findings have mostly been confirmed by additional tests, namely by employing an instrumental variable (IV) approach and quantile egression (QR).

This study contributes to the literature in different ways. First, it provides empirical evidence of the effect that entrepreneurship has on countries´ sustainable development in a holistic way, by separating its effect for the five pillars of sustainable development. Second, by investigating the different types of entrepreneurship, this study highlights that the motivation underlying entrepreneurial activities can influence the ability of entrepreneurs to create sustainable businesses. Finally, it also highlights the role of foreign investors in the achievement of SDGs.

This study presents several limitations. First, our entrepreneurial measure is not limited to social or sustainable entrepreneurs, as it includes all types of entrepreneurship. Our entrepreneurship variables measure the proportion of individuals engaged in entrepreneurial activities without discriminating any social or sustainability orientation. Although we tried to measure social entrepreneurial activity, our results were not statistically significant. The results are available on request. Therefore, we are not able to effectively measure sustainability and social-oriented entrepreneurship. Second, measuring national SDG is challenging, as interaction effects, trade-offs, and vaguely defined goals exist [

71]. Another limitation of this study is the relatively small number of countries considered in the analysis, and more specifically, the lack of low-income countries due to data unavailability. Considering that the low-income countries may be the ones that need the most investment in entrepreneurship and sustainable growth, further research should be conducted in this subject. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the negative impact of entrepreneurship is more prevalent in countries with lower SDGs scores. These countries are characterized by weak business environments and large skill gaps, therefore specific models and methodology should be applied in future works [

80]. Nevertheless, this exploratory study advances the discussion of types of entrepreneurship and sustainability in countries with levels of development. Finally, we could have analysed the relationship between types of entrepreneurship and SDGs by grouping observations in a different way (e.g., countries grouped by population or income level). These types of analyses could potentially lead to different results, creating the modifiable areal unit problem, as described in [

81]. Unfortunately, a lack of data prevents us from empirically testing these alternatives unit of analyses. Instead, we disaggregate SDGs in different dimensions (people, prosperity, planet, peace, and partnership) and evaluate the effect of entrepreneurship in points of the conditional distribution of the SDGs scores to ensure the stability of our data [

81]. Empirical strategies using alternative units of analysis warrants further research when data becomes available.