How Nonlocal Entrepreneurial Teams Achieve Sustainable Performance: The Interaction between Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Organizational Legitimacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

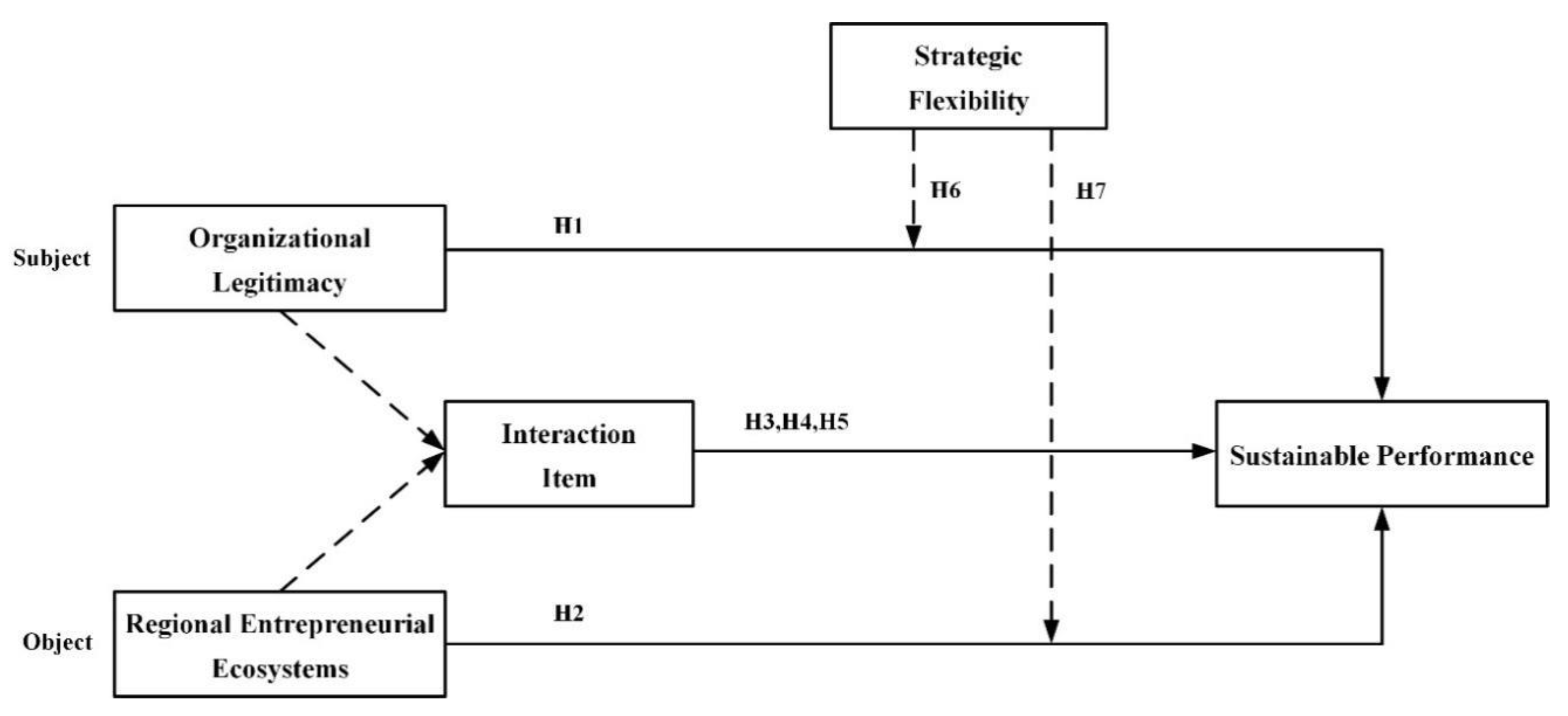

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Organizational Legitimacy and Sustainable Performance of Entrepreneurial Team

2.2. Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and Sustainable Performance of Entrepreneurial Team

2.3. Consistency and Inconsistency between Organizational Legitimacy and Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

2.4. Moderating Role of Strategic Flexibility

3. Method

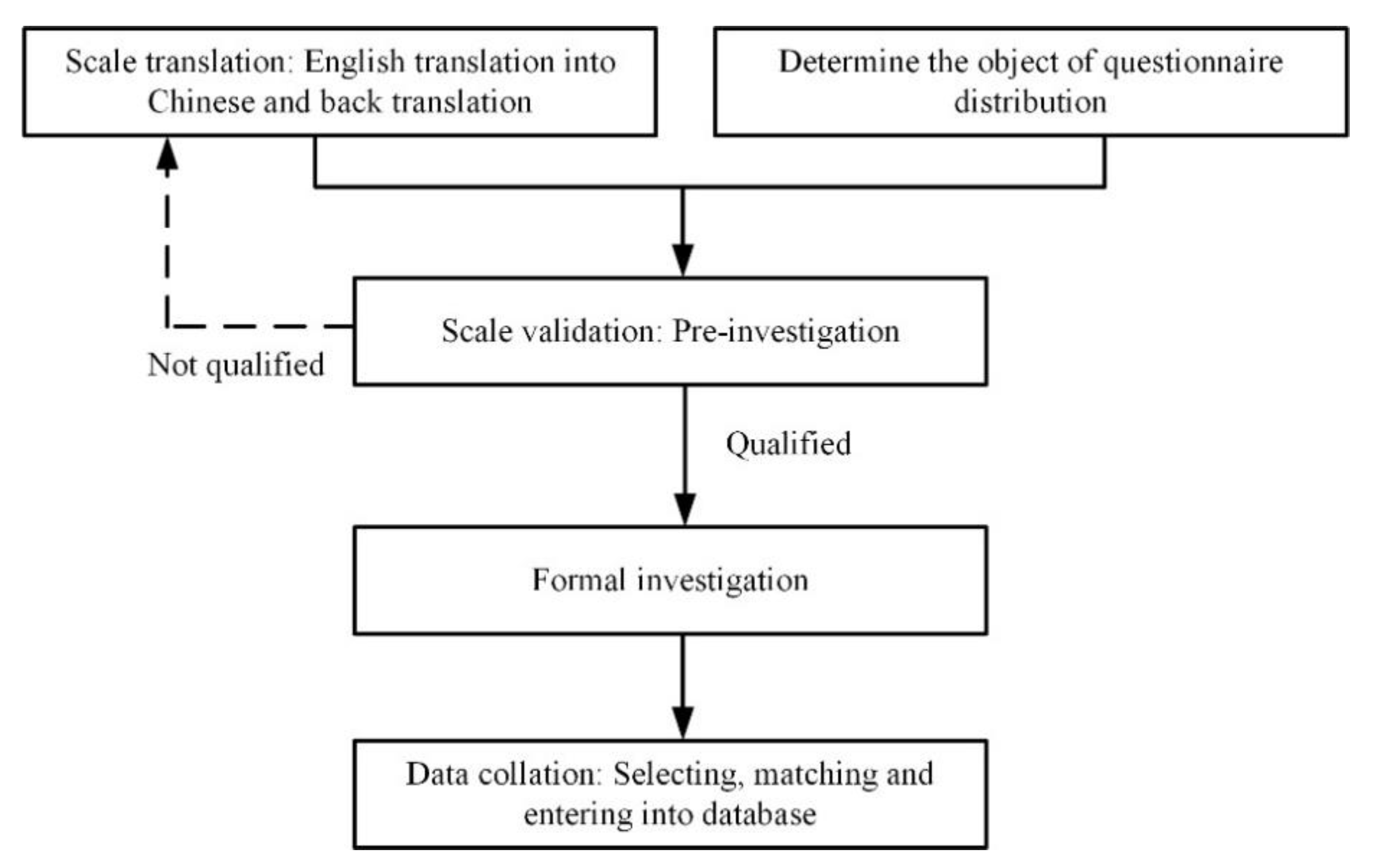

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Organizational Legitimacy (OL)

3.2.2. Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (REE)

3.2.3. Strategic Flexibility (SF)

3.2.4. Sustainable Performance (SP)

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

4.4.1. Hypotheses 1 to 3

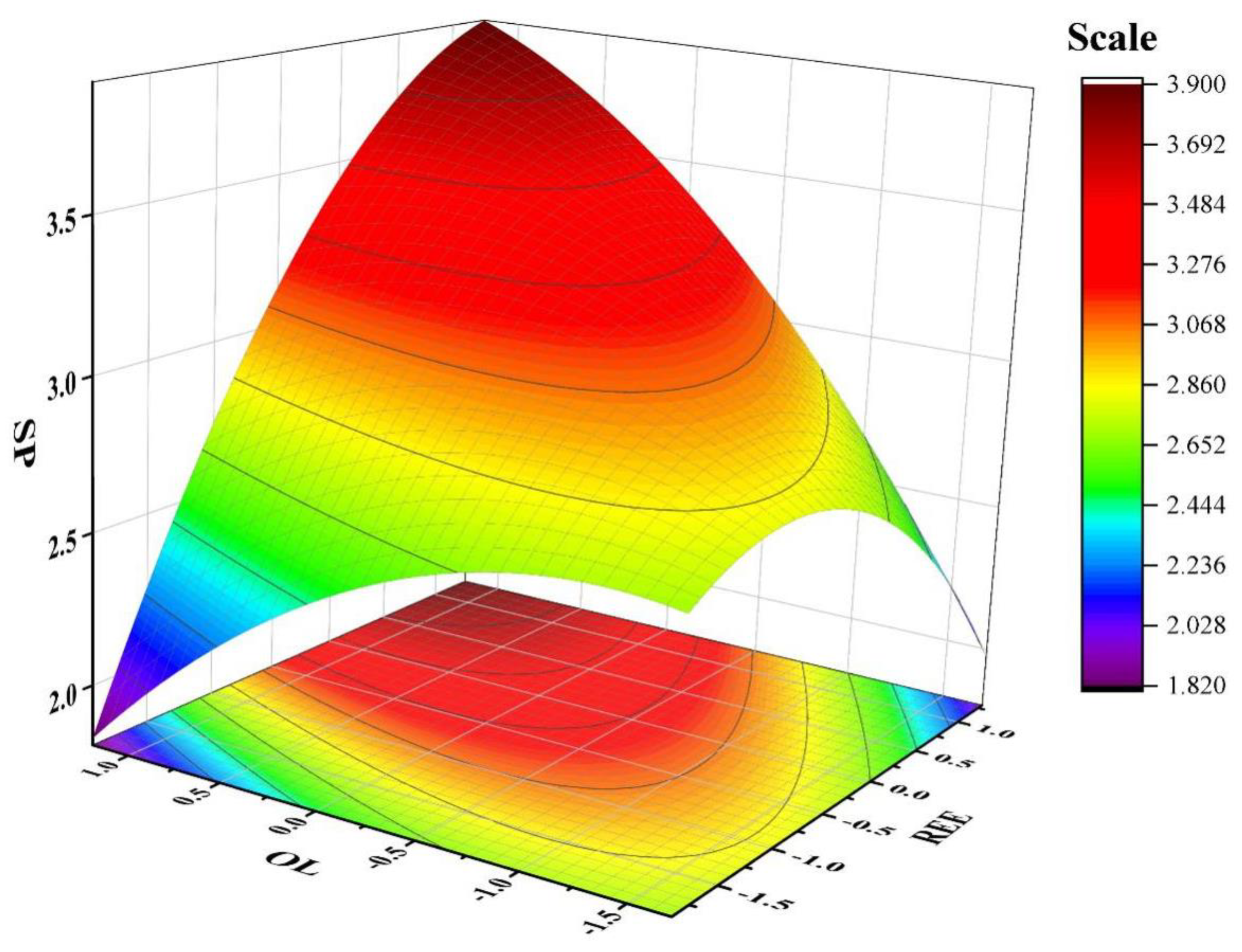

4.4.2. Hypotheses 4 and 5

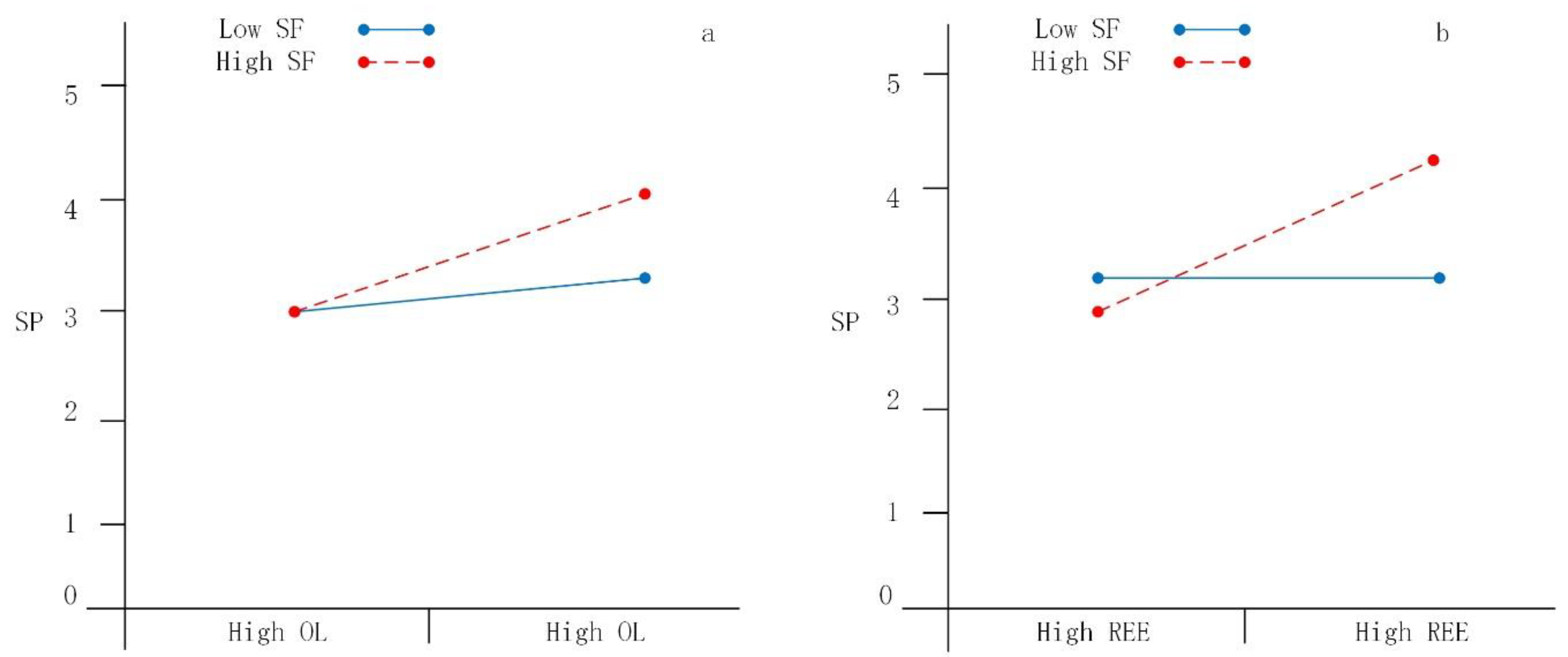

4.4.3. Hypotheses 6 and 7

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Conclusions and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Implications for Practice

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Organizational Legitimacy

- The exchange between us and our customers is reasonable and fair.

- We let customers participate in product production and service provision.

- We listen carefully to customers’ opinions in product production and service provision.

- The products and services we provide are popular.

- Our process of providing products and services is appropriate.

- Our technology for producing products and services is appropriate.

- Our institutional setup is understandable and appropriate.

- Our leaders and employees are attractive.

- We have become an indispensable part of local social life.

- In the eyes of local people, our existence is taken for granted and completely understandable.

- The locals all accept us.

Appendix A.2. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

- The region has a sufficient number of banks who are willing to lend to entrepreneurs.

- There are local individual investors in the region who are willing to financially support entrepreneurial venturing.

- Financing for entrepreneurship is available in this region.

- Local educational institutions offer specialized courses in entrepreneurship.

- There are entrepreneurial training programs, such as entrepreneurship boot camps, available in this region.

- There are ample local institutions of higher education.

- The diversity in this region provides a great test market for many other locations.

- My community networks could help me distribute new products across a variety of new markets.

- The region’s multinational diversity helps keep me connected the global economy.

- The local government actively seeks to create and promote entrepreneurship-friendly legislation.

- The local government has programs in place to help new entrepreneurs, such as seed funding programs or entrepreneurship training programs.

- Regional leaders regularly advocate for entrepreneurs.

- The social values and culture of the region emphasize creativity and innovativeness.

- The social values and culture of the region encourage entrepreneurial risk-taking.

- The social values and culture of the region emphasize self-sufficiency, autonomy, and personal initiative.

- The region has the infrastructure necessary to start, and run most businesses.

- Professional services for entrepreneurs are readily available in this region.

- I believe the resources in this region are well designed to support business growth.

Appendix A.3. Strategic Flexibility

- Resources are highly shared among all departments of the team.

- We can actively respond to external competition.

- We can quickly find new resources or new combinations of existing resources.

- The cost of changing the use of resources is lower.

- It takes less time to find alternative resources.

- We quickly arrange resources through the organization system and apply them to the target use.

Appendix A.4. Sustainable Performance

- Provides employment to us and others.

- Sales growth.

- Income stability.

- Return on investment.

- Ensures basic needs for our family.

- Enhances our social recognition in society.

- Improves our empowerment in society.

- Provides freedom and control.

- Uses utilities in an environment-friendly manner.

- Produces few wastes and emissions.

- Concerned about waste management.

- Concerned about hygiene factors.

References

- Chen, C.; Zhan, Y.; Yi, C.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Psychic distance and outward foreign direct investment: The moderating effect of firm heterogeneity. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1497–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, C.Y. Immigrant entrepreneurship and economic development. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Koveos, P.; Zhu, X.; Wen, F.; Liao, J. Outward FDI and Entrepreneurship: The case of China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N. How strategic entrepreneurship and the institutional context drive economic growth. Strat. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What do we know and what do we still need to know? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliere, D.; Peterson, R. Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Evidence from emerging and developed countries. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2009, 21, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinillos, M.; Reyes, L. Relationship between individualist–collectivist culture and entrepreneurial activity: Evidence from global entrepreneurship monitor data. Small Bus. Econ. Group. 2011, 37, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.J. Internal and external networks, and incubatees’ performance in dynamic environments: Entrepreneurial learning’s mediating effect. J. Tech. Transf. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.; Keilbach, M. Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.; Armington, C. Employment growth and entrepreneurial activity in cities. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.F.; Dean, T.J.; Payne, D.S. Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Song, H.K.; Lee, C.K. Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewatsch, S.; Kleindienst, I. How organizational cognitive frames affect organizational capabilities: The context of corporate sustainability. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; Brush, C.G. Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O.; Patswawairi, T. The motivations and obstacles to immigrant entrepreneurship in South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 32, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.D. Sustainability-driven entrepreneurship: Principles of organization design. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneuship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Understanding the social role of entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, Y.; Kaandorp, M.; Elfring, T. Toward a dynamic process model of entrepreneurial networking under uncertainty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, M.J.; Ketchen, D.J.; Shook, C.L. Understanding strategic entrepreneurship: A “theoretical toolbox” approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 631–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yang, X. From human capital externality to entrepreneurial aspiration: Revisiting the migration-trade linkage. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Bruton, G.D.; Si, S.X. Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: Insights on the construction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Li, S.; Safdar, M.; Khan, Z. The role of entrepreneurial strategy, network ties, human and financial capital in new venture performance. J. Risk. Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; Praag, M.V.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K.; Mentzer, J.T.; Zsomer, A. The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.; Ruef, M.; Mendel, P.J.; Caronna, C.A. Institutional Change and Healthcare Organization: From Professional Dominance to Managed Care; University of Chicago press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Luo, Y. Guanxi and organizational dynamics: Organizational networking in Chinese firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Shen, R.; Su, Z. The impact of organizational legitimacy on product innovation: A comparison between new ventures and established firms. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 66, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.T.; Hodge, F. Top management team prestige and organizational legitimacy: An examination of investor perceptions. J. Manag. Issues 2007, 19, 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. The population ecology of organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 929–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E.; Bendickson, J.; Solomon, S.; McDowell, W.C. Development of a multi-dimensional measure for assessing entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Moodysson, J.; Martin, H. Path renewal in old industrial regions: Possibilities and limitations for regional innovation policy. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerb, L.; Lafuente, E.; Horváth, K.; Páger, B. The relevance of quantity and quality entrepreneurship for regional performance: The moderating role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstad, S.J. Innovation strategy choices in the urban economy. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Santos, S.C. Sustainable business models, venture typologies, and entrepreneurial ecosystems: A social network perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4565–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, H.; Scott, P.; Gibbons, M. Rethinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin, R.; Henry, J.; Cuthbert, R. Acquiring market flexibility via niche portfolios: The case of Fisher and Paykel Appliance Holdings Ltd. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; García-Morales, V.J.; Pullés, D.C. Entrepreneurial decision-making, external social networks and strategic flexibility: The role of CEOs’ cognition. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Wu, F. Technological capability, strategic flexibility, and product innovation. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Wu, Y.; Goh, M. Hub firm transformation and industry cluster upgrading: Innovation network perspective. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1425–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.J.; Yang, M.G.; Park, K.; Hong, P. Stakeholders’ pressure and managerial responses: Lessons from hybrid car development and commercialization. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2015, 18, 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, R.; Mancini, M.; Turner, J.R. Community’s evaluation of organizational legitimacy: Formation and reconsideration. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, C.; Massini, S.; Lewin, A.Y. Sources of variation in the efficiency of adopting management innovation: The role of absorptive capacity routines, managerial attention and organizational legitimacy. Organ. Stud. 2014, 35, 1343–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A. Individual and environmental determinants of entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, G. An analysis of entrepreneurial environment and enterprise development in Hungary. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2001, 39, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz-Eakin, D.; Joulfaian, D.; Rosen, H.S. Entrepreneurial decisions and liquidity constraints. Rand J. Econ. 1994, 25, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D.J. Applying the Ecosystem Metaphor to Entrepreneurship. Antitrust. Bull. 2016, 61, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Prokop, D.; Thompson, P. Entrepreneurship and the Determinants of Firm Survival within Regions: Human capital, growth motivation and locational conditions. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 357–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.M.; Dilts, D.M. Inside the black box of business incubation: Study b-scale assessment, model refinement, and incubation outcomes. J. Technol. Transf. 2008, 33, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetanto, D.P.; Jack, S.L. Business incubators and the networks of technology-based firms. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 38, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatten, T.C.; Greve, G.I.; Brettel, M. Absorptive capacity and firm performance in SMEs: The mediating influence of strategic alliances. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2011, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Botelho, T. The role of the exit in the initial screening of investment opportunities: The case of business angel syndicate gatekeepers. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Goodale, J.C.; Byun, G.; Ding, F. Strategic flexibility in new high-technology ventures. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 55, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, J.; Essling, C.; Peukert, C. Demand variation, strategic flexibility and market entry: Evidence from the US airline industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2877–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Valls, M.; Cespedes-Lorente, J.; Moreno-Garcia, J. Green practices and organisational design as sources of strategic flexibility and performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, D.; Acur, N. Examining proactive strategic decision-making flexibility in new product development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Strategic flexibility in product competition. Strat. Manag. J. 1996, 16, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combe, I.A.; Greenley, G.E. Capabilities for strategic flexibility: A cognitive content framework. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 1456–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Elango, B. Managing strategic flexibility: Key to effective performance. J. Gen. Manag. 1995, 20, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Scherer, A.G. Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Quaddus, M. Development and Validation of a Scale for Measuring Sustainability Factors of Informal Microenterprises: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 48, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.J.Q.; Lim, V.K.G. Strength in adversity: The influence of psychological capital on job search. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, M.D. The value of value congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Parry, M.E. On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 1577–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, G. The Complexities of New Venture Legitimacy. Organ. Theory 2020, 1, 263178772091388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; van de Ven, A. Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Bus. Econ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhausen, D.; Morgan, R.E.; Brozović, D.; Volberda, H.W. Re-examining strategic flexibility: A meta-analysis of its antecedents, consequences and contingencies. Br. J. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Lizcano-Álvarez, J.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Intellectual Capital: Sources of competitiveness and legitimacy in organizations’ management practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Raza, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Minai, M.S.; Bano, S. The impact of entrepreneurial business networks on firms’ performance through a mediating role of dynamic capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, B.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Lee, H. Outsourcing Strategies of Established Firms and Sustainable Competitiveness: Medical Device Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, X. How user-driven innovation and employee intrapreneurship promote platform enterprise performance. Manag. Decis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Luo, Z.; Hazen, B.; Hassini, E.; Foropon, C. Organizational capabilities that enable big data and predictive analytics diffusion and organizational performance: A resource-based perspective. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1734–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | Loading | Items | Loading | CA | Structural Validity | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational legitimacy (OL) | OL1 | 0.874 | OL7 | 0.738 | 0.856 | χ2/df = 1.279 CFI = 0.943 TLI = 0.919 RMSEA = 0.071 | 0.931 | 0.556 |

| OL2 | 0.800 | OL8 | 0.752 | |||||

| OL3 | 0.644 | OL9 | 0.883 | |||||

| OL4 | 0.632 | OL10 | 0.778 | |||||

| OL5 | 0.658 | OL11 | 0.808 | |||||

| OL6 | 0.570 | |||||||

| Regional entrepreneurial ecosystem (REE) | REE1 | 0.822 | REE10 | 0.765 | 0.914 | χ2/df = 1.301 CFI = 0.926 TLI = 0.903 RMSEA = 0.074 | 0.968 | 0.630 |

| REE2 | 0.608 | REE11 | 0.713 | |||||

| REE3 | 0.751 | REE12 | 0.835 | |||||

| REE4 | 0.777 | REE13 | 0.907 | |||||

| REE5 | 0.720 | REE14 | 0.897 | |||||

| REE6 | 0.804 | REE15 | 0.816 | |||||

| REE7 | 0.759 | REE16 | 0.793 | |||||

| REE8 | 0.741 | REE17 | 0.796 | |||||

| REE9 | 0.877 | REE18 | 0.849 | |||||

| Strategic flexibility (SF) | SF1 | 0.808 | SF4 | 0.767 | 0.884 | χ2/df = 1.724 CFI = 0.972 TLI = 0.940 RMSEA = 0.114 | 0.911 | 0.630 |

| SF2 | 0.706 | SF5 | 0.816 | |||||

| SF3 | 0.824 | SF6 | 0.864 | |||||

| Sustainable performance (SP) | SP1 | 0.863 | SP7 | 0.737 | 0.907 | χ2/df = 1.459 CFI = 0.936 TLI = 0.912 RMSEA = 0.091 | 0.953 | 0.630 |

| SP2 | 0.697 | SP8 | 0.823 | |||||

| SP3 | 0.841 | SP9 | 0.759 | |||||

| SP4 | 0.788 | SP10 | 0.821 | |||||

| SP5 | 0.827 | SP11 | 0.820 | |||||

| SP6 | 0.726 | SP12 | 0.807 |

| Variables | Items | Loading | Items | Loading | CA | Structural Validity | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational legitimacy (OL) | OL1 | 0.729 | OL7 | 0.672 | 0.903 | χ2/df = 3.239 CFI = 0.968 TLI = 0.959 RMSEA = 0.060 | 0.919 | 0.509 |

| OL2 | 0.875 | OL8 | 0.711 | |||||

| OL3 | 0.692 | OL9 | 0.664 | |||||

| OL4 | 0.690 | OL10 | 0.684 | |||||

| OL5 | 0.706 | OL11 | 0.681 | |||||

| OL6 | 0.724 | |||||||

| Regional entrepreneurial ecosystem (REE) | REE1 | 0.725 | REE10 | 0.779 | 0.952 | χ2/df = 2.948 CFI = 0.943 TLI = 0.935 RMSEA = 0.069 | 0.957 | 0.557 |

| REE2 | 0.786 | REE11 | 0.767 | |||||

| REE3 | 0.753 | REE12 | 0.695 | |||||

| REE4 | 0.728 | REE13 | 0.776 | |||||

| REE5 | 0.717 | REE14 | 0.765 | |||||

| REE6 | 0.751 | REE15 | 0.775 | |||||

| REE7 | 0.758 | REE16 | 0.749 | |||||

| REE8 | 0.742 | REE17 | 0.720 | |||||

| REE9 | 0.717 | REE18 | 0.726 | |||||

| Strategic flexibility (SF) | SF1 | 0.786 | SF4 | 0.792 | 0.882 | χ2/df = 4.255 CFI = 0.984 TLI = 0.971 RMSEA = 0.073 | 0.910 | 0.630 |

| SF2 | 0.797 | SF5 | 0.783 | |||||

| SF3 | 0.794 | SF6 | 0.810 | |||||

| Sustainable performance (SP) | SP1 | 0.860 | SP7 | 0.776 | 0.845 | χ2/df = 2.455 CFI = 0.975 TLI = 0.967 RMSEA = 0.049 | 0.953 | 0.632 |

| SP2 | 0.785 | SP8 | 0.716 | |||||

| SP3 | 0.797 | SP9 | 0.702 | |||||

| SP4 | 0.794 | SP10 | 0.821 | |||||

| SP5 | 0.848 | SP11 | 0.833 | |||||

| SP6 | 0.791 | SP12 | 0.801 |

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | TLI | RMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 2353.914 | 1022 | 2.303 | 0.910 | 0.911 | 0.905 | 0.046 | 0.046 |

| Three-factor model | 4616.314 | 1031 | 4.477 | 0.758 | 0.759 | 0.747 | 0.067 | 0.076 |

| Two-factor model | 6204.726 | 1033 | 6.006 | 0.652 | 0.653 | 0.636 | 0.089 | 0.090 |

| Single-factor model | 8979.428 | 1034 | 8.684 | 0.465 | 0.467 | 0.441 | 0.107 | 0.113 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 2.21 | 0.924 | ||||||

| 2. Scale | 2.61 | 0.769 | 0.138 ** | |||||

| 3. Type | 2.23 | 0.907 | −0.003 | −0.052 | ||||

| 4. OL | 3.41 | 0.553 | 0.014 | −0.059 | −0.060 | |||

| 5.REE | 3.64 | 0.702 | −0.029 | −0.064 | 0.063 | 0.085 * | ||

| 6. SF | 3.52 | 0.731 | −0.008 | 0.032 | 0.003 | 0.080 * | 0.025 | |

| 7. SP | 3.32 | 0.548 | −0.029 | 0.001 | −0.016 | 0.276 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.217 *** |

| Variables | SP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Age | −0.018 | −0.021 | −0.013 | −0.009 | −0.017 | −0.007 | −0.020 | −0.021 | −0.011 | −0.018 |

| Scale | −0.011 | 0.002 | −0.027 | −0.009 | −0.015 | −0.020 | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.027 | −0.033 |

| Type | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.018 |

| Direct effect | ||||||||||

| OL (b1) | 0.276 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.240 *** | |||||

| REE (b2) | 0.288 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.194 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.158 *** | |||||

| OL × REE (b5) | 0.261*** | 0.301 *** | ||||||||

| OL2 (b3) | −0.140 ** | |||||||||

| REE2 (b4) | −0.156 *** | |||||||||

| X = Y: Slope (m1 = b1 + b2) | 0.396 *** | |||||||||

| X = Y: Curvature (m2 = b3 + b4 + b5) | 0.005 | |||||||||

| X = –Y: Slope (n1 = b1 – b2) | 0.008 | |||||||||

| X = –Y: Curvature (n2 = b3 + b4-b5) | −0.597 *** | |||||||||

| Moderating | ||||||||||

| SF | 0.147 *** | 0.158 *** | ||||||||

| OL × SF | 0.179 ** | 0.156 *** | 0.158 *** | |||||||

| REE × SF | 0.195 *** | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.001 | 0.078 | 0.136 | 0.024 | 0.196 | 0.247 | 0.116 | 0.132 | 0.179 | 0.210 |

| ∆R2 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.135 | 0.023 | 0.195 | 0.050 | 0.115 | 0.016 | 0.178 | 0.031 |

| F | 0.221 | 12.706 *** | 23.710 *** | 3.680 ** | 29.425 *** | 24.544 *** | 15.749 *** | 15.249 *** | 26.237 *** | 26.681 *** |

| Moderating: Strategic Flexibility | Effect | SE | LCI | UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational legitimacy→Sustainable performance | ||||

| Low | 0.109 | 0.058 | −0.005 | 0.224 |

| High | 0.371 *** | 0.050 | 0.272 | 0.470 |

| Regional entrepreneurial ecosystem→Sustainable performance | ||||

| Low | 0.128 ** | 0.042 | 0.044 | 0.211 |

| High | 0.413 *** | 0.038 | 0.336 | 0.489 |

| Item | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Organizational legitimacy positively impacts the sustainable performance of the entrepreneurial team. | Supported |

| H2 | Regional entrepreneurial ecosystem positively impacts the sustainable performance of the entrepreneurial team. | Supported |

| H3 | The interaction between organizational legitimacy and the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem positively impacts the sustainable performance of the entrepreneurial team. | Supported |

| H4 | High consistency between organizational legitimacy and the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem produces a higher sustainable performance than low consistency. | Supported |

| H5 | The consistency between organizational legitimacy and the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem produces a higher sustainable performance than inconsistency. | Supported |

| H6 | Strategic flexibility has a positive moderating role between organizational legitimacy and the sustainable performance of the entrepreneurial team. | Supported |

| H7 | Strategic flexibility has a positive moderating role between the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem and the sustainable performance of the entrepreneurial team. | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Wan, W.; Wu, Y.J. How Nonlocal Entrepreneurial Teams Achieve Sustainable Performance: The Interaction between Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Organizational Legitimacy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219237

Liu L, Wan W, Wu YJ. How Nonlocal Entrepreneurial Teams Achieve Sustainable Performance: The Interaction between Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Organizational Legitimacy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):9237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219237

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Longjun, Wenhai Wan, and Yenchun Jim Wu. 2020. "How Nonlocal Entrepreneurial Teams Achieve Sustainable Performance: The Interaction between Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Organizational Legitimacy" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 9237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219237

APA StyleLiu, L., Wan, W., & Wu, Y. J. (2020). How Nonlocal Entrepreneurial Teams Achieve Sustainable Performance: The Interaction between Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Organizational Legitimacy. Sustainability, 12(21), 9237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219237