Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR), a current mainstream issue in global corporate governance, is often used to verify a company’s financial performance and corporate image; however, few studies have focused on CSR for environmental issues. On the basis of the perspectives of the expectation value and signal theories, this study presents a new concept for determining the impact of green shared vision (GSV) on employee environmental performance (EEP) and green product development performance (GPDP), which could aid in exploring the GSV–environmental CSR (ECSR) relationship further. The current results demonstrated that ECSR contributes to enhancing EEP and GPDP. Therefore, enterprises must implement the promotion of ECSR to enhance their overall green management performance and achieve sustainable management.

1. Introduction

With the increasing attention paid to adverse environmental conditions, such as climate change and ecological degradation, sustainable development has become a key development strategy for corporate environmental management [1,2]. Government departments have successively formulated strict environmental regulations to achieve environmental protection and have adopted various incentive policies and measures to encourage more environmental corporate behavior [3,4]. The increasingly severe environmental protection requirements have had considerable effects on the commercial environment [5,6]. Therefore, the influence of environmental protection on the rationale of enterprises is increasing [7]. For companies pursuing environmental performance, strategies and talent are essential factors [8]. Most companies must inspect and revise their basic statements, identifications, values, goals, visions, structures, operation principles, and relationships between stakeholders and thereby resolve environmental ecology problems [9,10]. In this context, the corporate green shared vision (GSV) will be essential for green management to gain a competitive advantage [11,12]. No organizational tool is more influential than vision [13].

Over the past few decades, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has increasingly attracted attention from scholars and enterprises [14]. Successful companies have incorporated CSR development into their shared vision, with CSR adopted as a sustainable development strategy, to benefit society and improve their own advantages in competition [15,16]. Therefore, enterprises are increasingly concerned about environmental issues [17] and are adding environmental protection to CSR, thereby enabling enterprises to increase productivity and reduce waste and emissions maximally [18]. Moreover, CSR covers a wide range of aspects. According to the Taiwan Corporate Sustainability Awards’ (2020) CSR report, CSR indicators are divided into seven aspects, including corporate sustainability vision and strategy and corporate governance performance. The current study thus focused on CSR for environmental issues. An increasing number of studies have focused on the factors that motivate enterprises to participate in environmental CSR (ECSR) and their impact on corporate performance [19,20]. In the interaction between enterprises and the natural environment, ECSR plays a key role in enhancing the trust relationship between enterprises and external stakeholders [21] and creating competitive advantages for enterprises [14]. This makes environmental strategy a CSR component and attracts attention in academic and corporate circles [22]. The promotion of environmental sustainability has become a strategy for enterprises to achieve a competitive advantage and the environmental responsibility needed by modern society [23].

Few empirical studies have focused on the impact of ECSR on employee environmental performance (EEP) and green product development performance (GPDP). The current research aimed to advocate ECSR and determine its impact. Therefore, to close the relevant research gap, we present an integrated model through the perspectives of expectancy–value theory and signal theory to discuss the effect of CSR promotion on employees and products under the premise of GSV with a sound system. We empirically analyzed our model by using the data of Taiwanese enterprises. Consequently, our empirical results provide two contributions for ECSR research. First, our results clarify the relationship between GSV, corporate governance, and EEP and further expand the ECSR–corporate sustainability strategy relationship. ECSR can improve employee environmental management performance and GPDP, and thus we further analyzed the actual impact and contribution to companies, which differs from previous discussions on the impact of ECSR on export performance [14], corporate financial performance [24], corporate and brand repute and corporate profitability [25], and legitimacy and firm performance [26]. Finally, the results support the goal of sustainable development strategy for Taiwanese enterprises. Although Taiwan is a global leader in semiconductor technology development, Taiwanese enterprises, dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, face the challenges related to environmental awareness, climate greenhouse effect, and extreme climate. To cope with this trend, all enterprises have begun to adjust their organizational management model over time. With the application of the signal theory perspective, this study considers GSV as a signal and ECSR as a signaler for companies to promote environmental behavior. We further discuss whether ECSR contributes to green management performance of the small and medium-sized companies in Taiwan.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Impact of GSV on Green Performance of Enterprises

The impact of corporate shared vision on an organization is crucial in enterprise management. Shared vision provides organizational employees with appropriate criteria and ideal goals to convince them that the challenges they can overcome effectively will affect their work behavior [27]. Shared vision adds meaning to employees’ work [28] and helps them improve their organizational satisfaction. When employees have a better understanding of corporate vision, their vision-driven implementation is more successful [29]. Therefore, shared vision is the common goal set by the high-ranking members of an organization for future development, conveying norms and beliefs to employees, inspiring them to exceed work performance expectations, and providing an ideal blueprint for future organizational strategies [11]. Shared vision can connect employees of different units and individuals within the organization because it establishes a shared value of organizational objectives and a correct behavior to realize them [30]. When an organization carefully designs its vision, it contributes toward guiding the actions and decisions of the employees and encouraging them to move toward their shared vision [31]. Chen, Chang, and Lin [32] proposed that an organization should aim for environmentally friendly and sustainable development and establish a GSV; in other words, the management should set a distinct corporate strategy direction for future organizational development aimed at environmental protection.

Incorporating environmental value into marketing strategies may enable enterprises to actually implement environmentalism and achieve competitive advantages [8]. In addition, it potentially conforms to the concept of expectancy–value theory, which is a cognitive-motivation theory linking the motivation level or strength of an individual striving for a certain goal and expected product to achieve the expected goal and the incentive value or potency of the specific target [33]. Two types of expectations are applied in the concept of expectancy–value theory [34,35]; from the perspective of efficiency expectation, an expectation is “the belief that people can successfully perform the required behavior to produce results”, and a result expectation refers to “a person estimates that a particular behavior will lead to certain results” [36]. Therefore, from the expectancy–value theory perspective, when a company formulates a shared vision recognized by employees, employees perceive their work to be more meaningful. A shared vision further motivates the organizational members to express their willingness [37], provide corporate members with a prevailing strategic direction and a clear goal for endeavors [38], correctly guide the members’ actions [39], and ensure that employees’ compliance with regulations and social interaction and communication is consistent, all of which are related to EEP [40]. Hence, based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

GSV positively influences EEP.

Companies that actively engage in environmental protection will pass on long-term development goals to their employees and encourage them to achieve these goals to emphasize the greening of enterprises and improve corporate performance [41]. When they encounter the increasing concern of consumers for the environment and their willingness to pay more money, enterprises invest in the research of green products, enabling green products to take advantage in market competition [42]. Therefore, how companies improve the performance of green product development is important. When companies formulate environmental strategies, the improvement of environmental performance depends on whether managers and employees have a shared vision, particularly employees with intensive participation in environmental strategies [9]. Therefore, team members must establish a shared vision and often interact and practice team reflection, which can aid in improving the performance of the team and of the green product development [43].

How a company effectively develops environmentally friendly products and services and green and innovative products to meet the growing consumer demand for environmental protection has become the key to success of a business [44,45,46]. GPDP involves a product development process. The developed product causes less damage to the environment and human health. It is formed using recyclable materials and provided to the market using an energy-saving process or less packaging [47]. Moreover, the GSV drives market changes and the company’s competitiveness. The specific approach involves formulating an organizational environmental governance strategy. The strategy in combination with the GSV can facilitate green product development and promote the organization’s sustainable development [11]. In summary, a well-defined corporate shared vision can contribute to organizational performance [9,32,43]. Therefore, according to expectancy–value theory, Chen et al. [48] stated that a GSV has a positive impact on GPDP. According to the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

GSV positively impacts GPDP.

2.2. Impact of ECSR on Resource Consumption and Results of Enterprises

CSR has been a sustainable development strategy for many enterprises to not only benefit society but also improve their competitive advantage [15,16]. The sustainable development of enterprises has been regarded as synonymous with CSR [49]. CSR has many benefits for enterprises; for instance: (a) CSR provides better working environment, close relationship with relevant stakeholders and communities, and greater commitment to environmental issues, which can increase employee engagement and confidence [50]; (b) CSR activities are important tools for image management, which can improve organizational legitimacy and shape public image [51,52]; and (c) CSR helps improve corporate financial performance [53,54,55,56]. According to the aforementioned studies, enterprises are required to participate in sustainable management and operation by integrating CSR measures [57]. CSR has become a critical success factor for organizations’ operation and management, involving a wide range of factors. Waddock and Graves [58] also indicated that CSR is multidimensional. With growing concerns about environmental issues in recent years, enterprises’ CSR has gradually incorporated environmental and social issues into operations and management [59]. ECSR has become part of CSR. Therefore, environmental protection awareness has allowed companies to attain a sustainable competitive advantage [60]. Xu, Zeng, and Chen [14] also indicated that ECSR could aid enterprises in building trust with external stakeholders and enhancing competitive advantage and corporate performance [61].

Williamson, Lynch-Wood, and Ramsay [62] specified that the concept of ECSR is an additional effort to integrate environmental issues with business operations and interaction with stakeholders, and an enterprise with ECSR is considered to balance and improve environmental damage without affecting its economic performance. Furthermore, ECSR contributes to sustainable development and is associated with resource and energy efficiency [63]. In other words, ECSR is achieved when an enterprise reduces the degree of environmental pollution and consumption of natural resources in the production process of the product and increases the recycling rate of the product [26]. Han et al. [8] indicated that ECSR is a means to reduce the harmful effects of the company on the environment and ecosystem. In summary, ECSR consists of providing consumer products with manufacturing processes and services that can reduce environmental and ecological pollution and natural resource consumption and effectively improve product recycling and reuse strategies. ECSR is essential in the legality of corporate environmental protection [64,65,66] and in obtaining related resources [67]. Companies gain legitimacy by showing that they meet a range of different shareholder expectations [68]. According to Connelly et al. [69], signal theory is a concept including four elements: signal, signaler, signal receiver, and feedback. An organization requires GSV research to establish a corporate strategic direction based on environmentally friendly and sustainable development. The management level sets a clear corporate environmental protection goal for the future development of the organization, establishes the expectations and value of green management and sustainable development of the enterprise as the signal of the signal theory, reduces the environmental and ecological pollution and the consumption of natural resources through the signaler ECSR effectively, and increases product recycling effectively. Therefore, based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

GSV positively impacts ECSR.

Currently, attention from government and environmental protection organizations is leading to enterprises facing increased pressure for environmental preservation [9,70,71]. Because of increasing restrictions on the natural environment and the related interests, individuals have increased sustainability requirements. Enterprises should thus adopt positive environmental strategies to demonstrate their environmental management efforts [72]. Several studies have explored corporate participation factors for ECSR and their impacts on corporate performance [9,19,20,73]. CSR activities, particularly environmental activities, are the source of creation. Appropriate CSR strategies can improve corporate financial performance [74,75]. Positive attitudes and firm commitment to pollution reduction and environmental protection have helped companies build a good reputation and image and enhance their competitive advantage [72,76]. We thereby concluded that ECSR, part of CSR, is vital in enterprise and the natural environment [21]. With the increasing number of environmental laws and regulations, enterprises have realized that successful green products can help companies gain benefits and move toward sustainable environmental development [47,50]. In this case, companies are increasing emphasis on product redevelopment and redesign to meet the consumer demands for green products [77]. The implementation of environmental protection thus becomes the social responsibility of enterprises, and new green product development can aid them in achieving sustainable success [78]. Therefore, the promotion of CSR can aid enterprises in improving their flexibility; in creating more opportunities to resolve social issues with innovative products or services; and in attracting, retaining, and further benefiting from new information—thereby improving the success of green products [79].

In summary, the attention paid to green product development is increasing with the increasing awareness of the importance of environmental protection [80,81]. Through environmentally responsible management and ECSR activities, companies have improved their overall environmental image and enhanced their reputation; ECSR has thus become an essential requirement for the success of many companies providing varied products or services [82].

Environmental strategies such as developing sustainable products and procedures also produce a positive effect on the environment as well as extend business life and public perceptions of responsibility [60]. Based on the concept of signal theory elements of Connelly et al. [69], in this research, in EEP, employees comply with regulations with consistent social communication. The GPDP process causes less damage, has low negative impact on the environment, is less harmful to human health, uses recyclable materials, and adopts more energy-saving processes or a reduced amount of packaging. This can be considered the signal receiver (EEP is the response of the employee to the signaler) and feedback (GPDP is the response of the employee to the signaler) from signal theory [69]. Therefore, when the company formulates a GSV, it establishes the company’s green management expectations and value signals, which are transmitted to the signal receivers (company employees and related stakeholders) through signalers (ECSR managers). In the ECSR context, the company provides related resources, and the employees feel the support of the organization and work harder [83]. Therefore, the research makes the following inferences from the expected value and signal perspective: (1) On the basis of the perspective of expectancy–value theory, a GSV can aid in improving employee behavior [11,27,29,84] and GPDP [11,48]. (2) According to signal theory, GSV can transmit signals to the receiver through the signaler and can thus improve GPDP [85,86,87]. (3) The signal must pass to the receiver through the signaler; otherwise, the signal receiver cannot receive the message [69]. Therefore, ECSR has an intermediary role, and this article proposes the following Hypotheses 4 (H4), 5 (H5), 6a (H6a), and 6b (H6b):

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

ECSR positively impacts EEP.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

ECSR positively impacts GPDP.

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

ECSR mediates the GSV–EEP relationship.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

ECSR mediates the GSV–GPDP relationship.

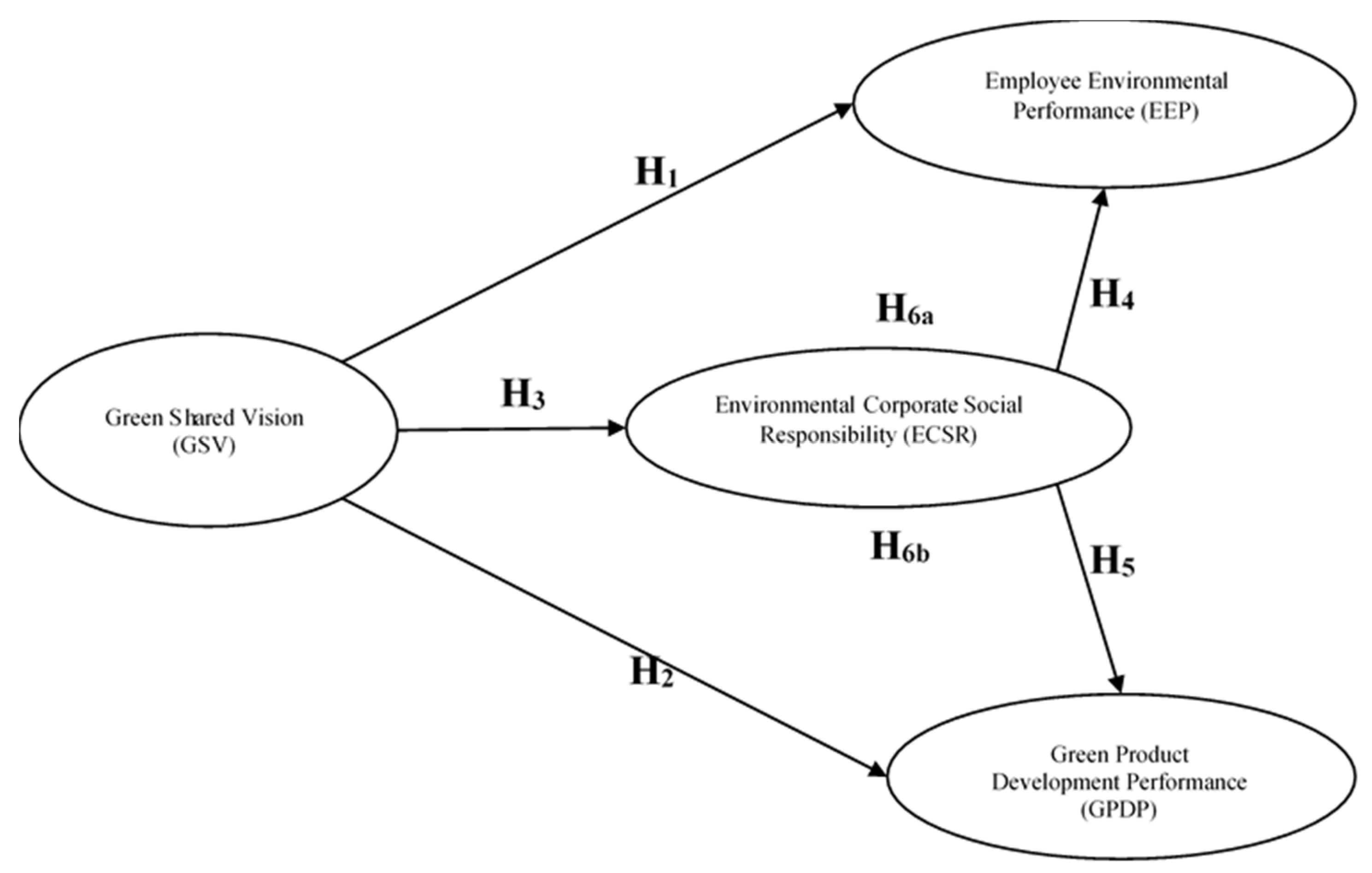

According to previous hypotheses and relevant research, this article summarizes the research framework (Figure 1) and adopts the theory of expectation value to further discuss the positive impact of GSV on EEP, GPDP, and ECSR through signal theory.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Methodology and Measurement

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

In this study, the levels of sales and research and development (R&D) were considered analysis units. Moreover, the research hypotheses and framework of Taiwan’s manufacturing industry were verified using a questionnaire. The reasons for the industry theme of the survey were as follows. First, Taiwan’s manufacturing industry mainly focuses on export; thus, it is bound by strict environmental regulations, such as the Montreal Convention, Kyoto Protocol, and EU directives on Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) and Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Therefore, products manufactured by enterprises should be consistent with consumers’ environmental regulations [81]. With the increasingly stringent global environmental laws and regulations, Taiwan’s manufacturing industry is facing major challenges. Thus, the sources and results of its ECSR warrant investigation. Second, because most manufacturing enterprises in Taiwan own fewer resources than other multinational enterprises do [88], understanding how environmental management performance could be promoted under the premise of insufficient resources is crucial. Finally, in Taiwan, an emerging manufacturing base, the current environmental regulations have become particularly stringent. Thus, for enterprises, further exploring the impact of Taiwanese manufacturing enterprises on ECSR and GPDP by shaping their GSV could be beneficial. The current findings, related to Taiwan’s manufacturing industry, might facilitate the development of a relevant theory.

The sample of the questionnaire in this study was selected randomly from the “Taiwan Business List”. The selected companies’ personnel or sales-related departments were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the research; the companies were also asked to specify whether they had any sales or R&D related to green product projects underway. The respondents were executives and employees from the companies’ sales, marketing, R&D, and business development departments. If the respondents consented to participation, the research objectives and questionnaire content were explained to them. Moreover, the respondent units were asked about the number of questionnaires to be sent. A return envelope was attached, with a request to send back the responses within 2 weeks of receipt so as to increase the questionnaire response rate. The respondents received small gifts after they completed the questionnaire. In this study, to reduce common method variation (CMV) problems and to prevent our research from violating the factors that MacKenzie and Podsakoff [89] pointed out most often causing CMV, when we designed the questionnaire, we concealed the information of the respondents, did not show the meaning of item design, and randomly allocated items. Cacioppo and Petty [90] suggested that increasing personal relevance of the task helps to fill in gaps in what is recalled, therefore avoiding the CMV. We then conducted surveys of respondents in different industries, departments, and positions. Based on the abovementioned questionnaire layout and design, we surveyed respondents in different fields to reduce CMV issues.

In this study, respondents of different industries, departments, and job levels helped reduce common method variance. Of the 986 questionnaires sent to the companies, 571 valid responses were recovered (effective response rate = 57.91%). Of all participating companies, 203 (35.6%), 221 (38.7%), 40 (7%), 60 (10.5%), and 47 (8.2%) had capitals of <10 million, 10–50 million, 50–100 million, 100 million–1 billion, and >1 billion, respectively, and 236 (41.3%), 218 (38.2%), 63 (11%), 13 (2.3%), and 41 (7.2%) had <50, 50–100, 100–500, 500–1000, and >1000 employees, respectively (Table 1). Thus, the current samples were mainly small and medium-sized companies.

Table 1.

Sample distribution by industry classification.

3.2. Definitions and Measurements of the Constructs

The study questionnaire contained four measurement dimensions: GSV, ECSR, EEP, and GPDP. The questionnaire was developed according to the advice of relevant scholars (Appendix A), and the questionnaire items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The respondents rated the items by checking relevant boxes on the questionnaire. This study cited the questionnaires developed by relevant scholars, which may still produce relevant errors, so exploratory factor analysis verification was used, and principal component analysis and orthogonal rotation with varimax were employed. The results show that Bartlett’s test and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy met the standard value [91] suitable for exploratory factor analysis. There were 18 items and four components in the analysis, and component names were the same as the names in the original construct: green shared vision (GSV), environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR), employee environmental performance (EEP), and green product development performance (GPDP) (see Table 2). The reliability coefficients for GSV, ECSR, EEP, and GPDP dimensions were 0.91, 0.935, 0.938, and 0.918, respectively. These values are higher than the standard value of 0.7 proposed in Nunnally and Bernstein [92], indicating high reliability of the adopted questionnaire.

Table 2.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Bartlett’s test, and rotated component matrix results.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

Table 3 presents the mean, standard deviation, average variance extracted (AVE) root mean square, and correlation coefficient values of all facets of the research framework.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the constructs.

Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [93] pointed out that the method of Fornell and Larcker [94] would be overestimated. Therefore, this study further used the average heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) to calculate the correlation ratio between the various dimensions. Table 4 shows that the construct’s HTMT proportions are all less than 0.85, which shows that the study’s constructs have good discriminative validity.

Table 4.

Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) analysis of the study.

Table 5 shows the statistical significant factor load of all four surfaces (λ). The results demonstrated that the individual item factor load (λ) of the measurement model was >0.7, and according to Hulland [95], here, individual questionnaire items had good individual item reliability. Moreover, both composite reliability and Cronbach alpha values were >0.7, and according to Bagozzi and Yi [96], here, the questionnaire possessed good internal consistency reliability. In addition, AVE was used to measure discriminant validity [95]. For a questionnaire to have discriminant (or differentiated) validity, AVE and AVE square root should be higher than the correlation coefficients between different facets, whereas the AVE should be >0.5 for it to possess convergent validity. Table 4 indicates that the composite reliability values of GSV, ECSR, EEP, and GPDP were 0.911, 0.936, 0.939, and 0.918, respectively, all of which are >0.5 and thus have good convergent validity. In addition, as shown in Table 3, AVE root mean square values of GSV, ECSR, EEP, and GPDP are 0.848, 0.886, 0.891, and 0.832, respectively—all of which are higher than their correlation coefficients and thus have discriminant validity. Lastly, AVE values of GSV, ECSR, EEP, and GPDP were 0.719, 0.785, 0.793, and 0.692, respectively—all >0.5, confirming that all four facets had convergent validity (Table 5). Therefore, the questionnaire used in this study has acceptable reliability and validity.

Table 5.

Standardized direct, indirect, and total effects of the hypothesized model.

4.2. Structural Model Results

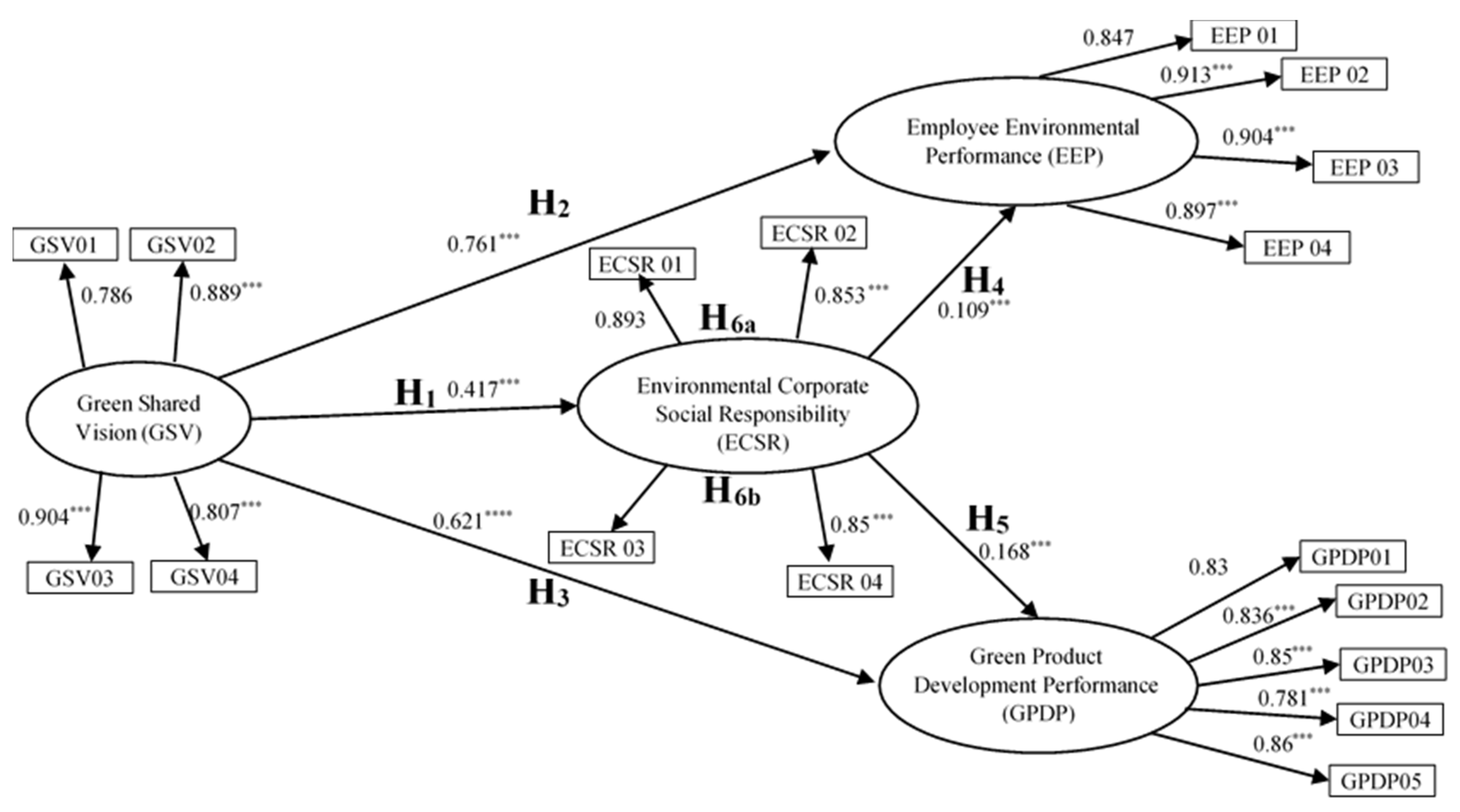

For structural equation modeling (SEM), data were included in the fit mode (model or equation), and then their suitability for the module (i.e., goodness of fit) was tested. Compared with traditional statistical methods, the differences are as follows. (1) Previous multivariate analysis techniques could not account for measurement errors. (2) The latent variable relationship was described in advance (the related intervariable pattern was specified a priori). (3) Both observed and unobserved variables were considered. (4) Path analysis almost discarded the measurement model to include only the structured model and considered the single path alone. (5) SEM was used as an overall test to prevent excessive expansion of type I error caused by multiple hypothesis tests. Babin, Hair, and Boles [97] and Nunkoo, Ramkissoon, and Gursoy [98] also reported that SEM is a more widely used tool that can be used to test various types of theoretical models. Therefore, we used SEM for hypothesis analysis and verification by using AMOS 26 in this study. Figure 2 illustrates that the full model adaptation is acceptable (chi-square/free degree = 3.255, GFI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.0457, TLI = 0.965, NFI = 0.958, and CFI = 0.97) and displays the experimental results of the full model. All the five paths directly correlated with the full model, demonstrating significant positive effects. Thus, H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 are supported in this study.

Figure 2.

Full model results. GFI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.063, NFI = 0.958, CFI = 0.97, RMR = 0.037. Note: *** p < 0.001.

These results demonstrate that increased application of GSV and ECSR can improve EEP and GPDP; thus, GSV and ECSR are the key factors of green management in enterprises. According to the mediating effect test of Baron and Kenny [99], the GSV→ECSR, GSV→EEP, GSV→GPPD, ECSR→EEP, and ECSR→GPDP correlations are direct and positive. Moreover, ECSR has a mesomeric effect, and the relationship among GSV, EEP, and GPDP is mediated by ECSR.

To ensure rigor in the study, 5000 bootstrap replications were performed. The percentile bootstrap and bias correction percentile bootstrap test research models were performed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) [100]. The results demonstrated that both the mediation relationships (i.e., GSV→EEP and GSV→GPDP) were supported. In the mediating model, the values for standardized direct, indirect, and total effects of the GSV→EEP and GSV→GPDP relationships were respectively 0.761 (z = 24.548) and 0.621 (z = 15.923), 0.045 (z = 3) and 0.07 (z = 3.889), and 0.806 (z = 33.917) and 0.691 (z = 24.065; all p < 0.001). The mediating effect is nonsignificant when zero is included within the 95% CIs [101]. Nevertheless, here, the mediating effect was significant because there was no zero between the lower and upper limits of 95% CI for each indirect effect (Table 6). Therefore, H6a and H6b were also supported. Thus, the current intermediary model confirmed that ECSR has an intermediary role.

Table 6.

Standardized direct, indirect, and total effects of the hypothesized model.

Table 7 presents the results of the complete model. All six paths demonstrated considerably positive results, thus supporting H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6a, and H6b. Thus, GSV can improve EEP and GPDP through ECSR. In addition, GSV is positively correlated with EEP and GPDP, and ECSR has a partial mediating effect, but the partial mediating effect does not completely conform to the signal theory, and the receiver needs to transmit the concept of information through the signaler. This study only explores ECSR and does not contain governors and managers. In the future, the relationship between governors and managers may be explored and clarified and the theoretical model verified further. In addition, the results also indicate that GSV directly affects EEP and GPDP performance and generates a positive impact through ECSR. Therefore, we recommend that enterprises enhance employees’ GSV and ECSR to increase their EEP and GPDP.

Table 7.

Standardized direct, indirect, and total effects of the hypothesized model.

5. Conclusions and Implications

By applying the expectancy–value and signal theory perspectives, this study proposed an integrative research framework to explore the GSV→ECSR relationship further, with a focus on the impact of the green-oriented performance of employees and products. The results indicated that (1) GSV has a substantial and positive effect on ECSR, EEP, and GPDP; (2) ECSR can result in an obvious and positive influence on EEP and GPDP; (3) ECSR partially mediates the GSV→EEP relationship; and (4) ECSR partially mediates the GSV→GPDP relationship. In summary, to improve environmental management performance, enterprises can create the vision and value of their employees’ common development by formulating a GSV of enterprises, thereby strengthening their motivations and positively modifying their behaviors and attitudes. In addition, ECRS plays an intermediary role. The sample of small and medium-sized enterprises in this study demonstrated that to improve EEP and GPDP, EEP alone is insufficient, and it can be influenced by GSV. The current results failed to comply with signal theory proposed by Connelly et al. [69] only with regard to the intermediary. Passing the signal to the receiver through the signaler is essential; otherwise, the signal receiver cannot receive the message. In this study, GSV was relatively simple because of the small-to-medium size of the sample enterprises. Thereby, signals could be conveyed relatively easily, and employee recognition could be obtained easily, such that GSV had a positive impact on the GPDP–EEP relationship. This point warrants further research.

This study investigated the frontline employees of R&D and sales departments of Taiwan’s electronic-information-related industries, department stores, and catering and leisure industries. This study thus has three limitations. First, the research results demonstrated that GSV can affect GPDP through ECSR and can directly affect GPDP; moreover, GSV had partial intermediary effects. (1) These results failed to comply with signal theory proposed by Connelly et al. [69] but only in relation to the intermediary, which is necessary to pass the signal to the receiver through the signaler. (2) In contrast to Chen et al. [48], the current study results indicated that GSV has no significant effect on GPDP, mainly because this study took green absorptive capacity as the benchmark for intermediary roles. However, the current results are consistent with those of Chang et al. [11]. GSV has a significant effect on GPDP. Moreover, the current study used green organizational citizenship behavior as an intermediary role viewpoint; that is, there may still be differences in the research of different benchmarks of intermediary role viewpoints. Second, this study used a horizontal research design; the current results may thus be different from those of studies involving longitudinal research on behavior and attitude at different times. (3) The frontline employees of the sales and R&D department of the sample companies were selected as the current research objects because they all wanted their products to be favored by consumers but were from different departments or job types—which may have led to confounding or biases. Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, we propose three managerial implications of corporate green management practice.

First, enterprises should devote themselves to the formulation of a GSV based on the view of expectancy–value theory. The challenge of sustainability builds considerable pressure on the organization but can lead to a more sustainable environment [102], and the success of the organization’s environmental sustainability measures depends on the employees’ environmental behavior [103]. Hence, many enterprises invest resources into strengthening their moral motivation because they believe that they can improve their green product innovation performance [104] and thereby achieve a competitive advantage. However, few discussions have taken place on whether enterprises should first establish a GSV through theoretical perspectives. Recent related studies have indicated that GSV contributes to enhancing the performance of green product development [11], green organizational citizenship behavior [11,12], green absorptive capacity [48], green exploitation learning, green exploration learning, green radical innovation performance, green incremental innovation performance [32], green mindfulness, green self-efficacy, and green creativity [105]. The results demonstrated that shaping the GSV of organizations is a key factor for green management performance. To make a broad vision effective, enterprises must incorporate GSV into the vision of others in the organization [106]. A shared vision should be based on the company’s potential for success as a forward-looking strategic foundation [107,108]. By using the expected value theory perspective, GSV should be customized and combined with the signal theory model to convey the concept of the organization’s management and vision goals and gain employees’ approval to help improve ECSR, EEP, and GPDP. Without the implementation of recognition, GSV may be turned into a slogan. Therefore, knowing how to formulate a GSV recognized by employees is key to promoting the sustainable development of the company.

Second, with the rise of ECSR, enterprises should pay attention to investing in succession. Considering the many challenges and considerable pressure on the environment, modern enterprises and governors have considered green innovation as a main factor of their long-term development so as to provide enterprises with competitive advantages [109]. An increasing number of organizations are adopting green policies and related measures to improve their economic efficiency and environmental performance [110]. Therefore, with the appearance of environmental sustainability and green enterprise management, corporate demand for ECSR is increasing [7]. The sample survey results mainly for small and medium-sized enterprises show that in addition to ECSR helping to improve the green performance of employees and product development, GSV also helps to improve ECSR, EEP, and GPDP. Thus, companies should promote the sustainable development of GSV, followed by that of ECSR.

Finally, enterprises need to establish their own green strategic development blueprint. Small and medium-sized enterprises have fewer resources than do listed and over-the-counter companies. Enterprise managers must actively allocate resources and budgets and use the characteristics of small and medium-sized enterprises that can rapid turnover and adaptability to enhance EEP and GPDP. The research results demonstrate that ECSR plays a mediator role in GSV, accompanied by EEP and GPDP. Therefore, in response to the environmental challenges and pressures, a company’s GSV formulation should be designed in accordance with the company’s structure and work characteristics to promote its overall green management performance. Thus, aligning GSV with the current state of corporate governance may help companies promote sustainable environmental performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-W.C.; Data curation, T.-W.C.; Formal analysis, T.-W.C.; Funding acquisition, T.-W.C.; Methodology, T.-W.C.; Resources, T.-W.C.; Writing—review and editing, Y.-L.Y. and H.-X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan: MOST 107-2410-H-606-002.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Constructs survey items.

Table A1.

Constructs survey items.

| Constructs | Items | Cronbach’s α | Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Content | |||

| GSV | GSV01 | A commonality of environmental goals exists in the company. | 0.91 | Chen, Chang, Yeh and Cheng [105] |

| GSV02 | A total agreement on the strategic environmental direction of the organization. | |||

| GSV03 | All members in the organization are committed to the environmental strategies. | |||

| GSV04 | Employees of the organization are enthusiastic about the collective environmental mission of the organization. | |||

| ECSR | ECSR 01 | Our products are more environmentally friendly | 0.935 | Wei, Shen, Zhou and Li [26] |

| ECSR 02 | Our production process requires fewer natural resources | |||

| ECSR 03 | Our production process decrease environmental pollution | |||

| ECSR 04 | Our products are easier to recycle for reuse | |||

| EEP | EEP 01 | I limit my environmental impact beyond compliance | 0.938 | Paille and Meija-Morelos [40] |

| EEP 02 | I prevent and mitigate environmental crises | |||

| EEP 03 | I comply with environmental regulations | |||

| EEP 04 | I educate other employees and the public about the environment | |||

| GPDP | GPDP 01 | The green product development project contributes a key source of revenues to the company. | 0.918 | Chen et al. [48] |

| GPDP 02 | The green product development project develops excellent green products. | |||

| GPDP 03 | The green product development project continually improves its development processes over time. | |||

| GPDP 04 | The green product development project is more innovative in green product development than its competitors. | |||

| GPDP 05 | The green product development project can meet its environmental goals in green product development. | |||

References

- Amran, A.; Ooi, S.K.; Mydin, R.T.; Devi, S.S. The impact of business strategies on online sustainability disclosures. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J.; Modig, F.; Vall, H.G. Commitment to sustainability in small and medium-sized enterprises: The influence of strategic orientations and management values. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Iatridis, K.; Kesidou, E. The impact of regulatory complexity upon self-regulation: Evidence from the adoption and certification of environmental management systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Peñasco, C.; Romero-Jordán, D. Distinctive features of environmental innovators: An econometric analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Environmental technologies and competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.P.; Huang, S.J. The effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on environmental performance and business competitiveness: The mediation of green information technology capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W. Turning corporate environmental ethics into firm performance: The role of green marketing programs. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Altma, B.W. Managing the Environmental Change Process: Barriers and Opportunities. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1994, 7, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, F.-F.; Luan, H.-D.; Chen, Y.-S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W. Corporate Sustainable Development Strategy: Effect of Green Shared Vision on Organization Members’ Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.C.; Porras, J.I. Building your company′s vision. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H. Signaling good by doing good: How does environmental corporate social responsibility affect international expansion? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Innovation Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 23, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Martín, P.J.; Rubio, A. Doing Good and Different! The Mediation Effect of Innovation and Investment on the Influence of CSR on Competitiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, P. Corporate Environmental Responsibility: Is a Common CSR Framework Possible; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, K.; Ryu, D. Corporate Environmental Responsibility: A Legal Origins Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shu, C.; Jiang, W.; Gao, S. Green management, firm innovations, and environmental turbulence. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 28, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, H.; Megicks, P.; Agarwal, S.; Leenders, M.A.A.M. Firm resources and the development of environmental sustainability among small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from the Australian wine industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wei, J.; Lu, L. Strategic stakeholder management, environmental corporate social responsibility engagement, and financial performance of stigmatized firms derived from Chinese special environmental policy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Johns, R. The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational mindfulness and mindful organizing: A reconciliation and path forward. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Orife, J.N.; Anderson, F.P. Effects of commitment to corporate vision on employee satisfaction with their organization: An empirical study in the United States. Int. J. Manag. 2010, 27, 421. [Google Scholar]

- Colakoglu, S. Shared vision in MNE subsidiaries: The role of formal, personal, and social control in its development and its impact on subsidiary learning. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C.K.; Tabone, J.C. Mission statement rationales and organizational alignment in the not-for-profit health care sector. Healthc. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, V.; Lens, W.; De Witte, H.; Feather, N.T. Understanding unemployed people’s job search behaviour, unemployment experience and well-being: A comparison of expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 44, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N.T. Expectancy-value theory and unemployment effects. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1992, 65, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N.T. Values, valences, expectations, and actions. J. Soc. Issues 1992, 48, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosik, J.J.; Kahai, S.S.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and dimensions of creativity: Motivating idea generation in computer-mediated groups. Creat. Res. J. 1998, 11, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.M.; Goethals, G.R. Individual and Group Goals; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Larwood, L.; Falbe, C.M.; Kriger, M.P.; Miesing, P. Structure and meaning of organizational vision. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 740–769. [Google Scholar]

- Paillé, P.; Meija-Morelos, J.H. Organisational support is not always enough to encourage employee environmental performance. The moderating role of exchange ideology. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The relationship between environmental commitment and managerial perceptions of stakeholder importance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, V.N. A blueprint for green product development. Ind. Manag. 1993, 35, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hofhuis, J.; Mensen, M.; Den, L.M.T.; Berg, A.M.V.D.; Koopman-Draijer, M.; Van Tilburg, M.C.; Smits, C.H.M.; De Vries, S. Does functional diversity increase effectiveness of community care teams? The moderating role of shared vision, interaction frequency, and team reflexivity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R.; Ramirez, E.; Martinez, J.D. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.-P.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, H.-Y. Simplified Neutrosophic Linguistic Multi-criteria Group Decision-Making Approach to Green Product Development. Group Decis. Negot. 2016, 26, 597–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiyeh, S.; Adaku, E.; Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Asante-Darko, D.; Amoatey, C.T. Environmental management practices, operational competitiveness and environmental performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 29, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, S.; Lin, C.; Hung, S.; Chang, C.; Huang, C. Improving green product development performance from green vision and organizational culture perspectives. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and Practice in a Developing Country Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conesa, J.A.; Nieto, C.D.N.; Briones-Peñalver, A.J. CSR Strategy in Technology Companies: Its Influence on Performance, Competitiveness and Sustainability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Clelland, I. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld, B.M.; Wurthmann, K.A.; Hambrick, D.C. The Stigmatization and Devaluation of Elites Associated with Corporate Failures: A Process Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kang, J.-K.; Low, B.S. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. J. Financial Econ. 2013, 110, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C. Misery′s child. Soc. Semiot. 1992, 2, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good and does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009, 1001, 41234–48109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, M.; Eweje, G.; Taskin, N. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility to Internal Stakeholders: Walking the Walk or Just Talking the Talk? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 26, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.Y.; Wang, C.; Meng, Y. An analysis of environmental corporate social responsibility. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2019, 40, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, M.; Ng, P.Y.; Ndubisi, N.O. Mindfulness, socioemotional wealth, and environmental strategy of family businesses. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Cin, B.; Lee, E. Environmental Responsibility and Firm Performance: The Application of an Environmental, Social and Governance Model. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2016, 25, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Lynch-Wood, G.; Ramsay, J. Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punte, S.; Repinski, P.; Gabrielsson, S. Improving energy efficiency in Asia’s industry. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 50, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.; Adegbite, E.; Rajwani, T. Corporate social responsibility in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts: Do institutional voids matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claasen, C.; Roloff, J. The link between responsibility and legitimacy: The case of De Beers in Namibia. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, H.A. Well known or well liked? The effects of corporate reputation on firm value at the onset of a corporate crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2103–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.A.; Rondinelli, D.A. Proactive corporate environmental management: A new industrial revolution. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G. Measuring corporate sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Adopting proactive environmental strategy: The influence of stakeholders and firm size. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1072–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Corporate boards and outside stakeholders as determinants of environmental litigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The porter hypothesis at 20: Can environmental regulation enhance innovation and competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, M.; Bloemhof, J.; van Raaij, E.; Wynstra, F. Proactive environmental strategy in a supply chain context: The mediating role of investments. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, D.; Peattie, K.; Wright, G. Organizational antecedents of environmental responsiveness in industrial new product development. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.G. The dimensions of industrial new product success and failure. J. Mark. 1979, 43, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Urriago, Á.R.; Barge-Gil, A.; Rico, A.M.; Paraskevopoulou, E. The impact of science and technology parks on firms′ product innovation: Empirical evidence from Spain. J. Evol. Econ. 2014, 24, 835–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lho, L.H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Ryu, H.B.; Park, J.; Kim, W. Factors triggering customer willingness to travel on environmentally responsible electric airplanes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Montabon, F. Engagement in environmental behaviors among supply chain management employees: An organizational support theoretical perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Shahjehan, A.; Afridi, S.A.; Nawaz, A.; Fazliani, H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ren, S.; Yu, J. Bridging the gap between corporate social responsibility and new green product success: The role of green organizational identity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorsson, M.; Bellgran, M.; Jackson, M. Sustainable Manufacturing-Challenges and Possibilities for Research and Industry from a Swedish Perspective. In Manufacturing Systems and Technologies for the New Frontier; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.K.S. Environmental requirements, knowledge sharing and green innovation: Empirical evidence from the electronics industry in China. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2013, 22, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E. The need for cognition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1958, 23, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Hair, J.F.; Boles, J.S. Publishing research in marketing journals using structural equation modeling. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H.; and Gursoy, D. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: Past, present, and future. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.Y. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, S.; Kim, E.J. The relationships between sociodemographic variables and concerns about environmental sustainability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee′s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. Do green motives influence green product innovation? The mediating role of green value co-creation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, H.P., Jr.; Lorenzi, P. The New Leadership Paradigm: Social Learning and Cognitions in Organizations; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alt, E.; Díez-de-Castro, E.P.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. Linking employee stakeholders to environmental performance: The role of proactive environmental strategies and shared vision. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R. Public policy and corporate environmental behavior: A broader view. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Dangelico, R.M. Firm environmental performance under scrutiny: The role of strategic and organizational orientations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).