1. Introduction

How does the electoral cycle affect cultural policies? What effect do elections have on local budgets for culture? Does public spending on culture have any impact on the re-election chances of city mayors? This paper seeks to identify whether there is a political cycle in local spending, i.e., whether in the year before a local election is held, governing politicians systematically increase budgets as a mechanism to increase their chances of winning elections. Furthermore, as cultural economists, we are particularly interested in whether this political cycle also occurs in the area of cultural expenditure, as opposed to expenditure on other merit goods such as health, education (both basic public services of a Welfare State), or sports.

Having analyzed the evidence on variations in local spending in an election year, we intend to discover if these variations have a measurable effect on the electoral success of the incumbent candidate or party. In other words, is there a causal relationship between increased spending in general, and in culture in particular, and enhanced chances of re-election?

It should be borne in mind that spending on culture can often attain greater public awareness than other types of public spending as activities related to artistic, creative, and entertainment expressions have, in the short term, a greater media impact. Therefore, we hypothesize that local governments will be tempted to favor spending on Culture over other types of spending in pre-election periods.

In order to observe this phenomenon in more precise terms, we have focused on medium-sized cities, trying to avoid the distortions of the “person effect” in small municipalities and the influence of large cycles of political change in larger cities where municipal elections can be influenced by the contagion effects of regional, national, and international trends and, therefore, be less determined by local dynamics. In small cities, local elections thus emphasize the individual candidate’s link to voters, with the proximity effect becoming predominant. This increases the relevance of the individual among the voting factors and decreases the weight of other motivations [

1]. In big cities, global political trends condition the orientation of voters who, even given the scale of the city, hardly notice marginal changes to local public spending decisions, which can be confused with regional or national government spending.

In order to contrast this hypothesis, a database has been elaborated for Spain where variations in public spending on culture, health, education, sports, and total municipal budget and different population characteristics (age groups, level of studies, unemployment rate, etc.) have been collected. A dichotomous variable has been included to record if the incumbent was successful or not (that is, to say if the party that governed in the previous period repeats). All these variables are considered for the 2011–2015 and 2015–2019 electoral cycles, adding up to a total of 700 cases (350 for each electoral cycle).

Our conclusions do confirm the initial hypotheses, showing that, at local level, both total expenditure and expenditure on culture are instrumentalized by the parties in government to achieve re-election and that, furthermore, while increases in other spending areas (such as education, health, or sports) do not have significant effects on the likelihood of re-election, variations in culture expenditure do have a significant effect on the probability of being re-elected.

2. Political Business Cycle (PBC), Revisited

There is extensive literature on the relationship between public spending and the political cycle at the level of central governments. At the local level, however, studies have been more limited.

The origins of the Theory of Political Budget Cycles can be found in the classic article by Nordhaus [

2] on the Theory of Political Business Cycle. Per Nordhaus, politicians in office have an incentive to use economic policy to boost the economy and to support their re-election. The phenomenon could be defined as «cycles in some component of the government budget induced by the electoral cycle. More specifically, the term most often refers to increases in government spending or the deficit or decreases in taxes (including changes relative to long-term trends) in an election year, which are perceived as motivated by the incumbent’s desire for re-election for himself or his party» [

3].

However, Brender and Drazen [

4] finally conclude that the political deficit cycle in democracies is found to be statistically significant only in the first few elections after a country has transitioned from being a non-democracy to a democracy (which holds true whether or not the formerly socialist economies are included), and the effect on mature democracies is virtually non-existent.

Basically, there are two main lines of research. On the one hand, politicians are supposed to increase the total budget, and on the other hand, they make changes in the composition of the budget, placing greater emphasis on more electorally visible items. Regarding the first group of papers, evidence has recently been found in Portuguese governments, considering aggregate expenditures, and budget deficit [

5], as well as at all levels of government [

6], while other works [

7] have proven the influence of electoral cycles on total expenditure in the new democracies of Eastern Europe.

As for the second group, we can say that there is abundant evidence concerning changes to the composition of the budget. The starting hypothesis is that governments increase spending on the most visible items to enhance their chances of re-election. Generally, expenditure on social welfare, infrastructure, environmental protection, and public services is prone to manipulation for electoral reasons [

7]. Thus, there are recent studies regarding pre-election increases in capital investment [

5,

8]. There is also evidence that governments increase the relative weight of education, social protection, and some sub-components of health expenditure [

6], as well as variations related to government ideology [

9], with the left more likely to increase spending on education and the right on public services. Several authors have also found that the electoral cycle has a special impact on social expenditure and infrastructure [

10].

2.1. Political Business Cycle in Local Expenditure

Recently, studies on PBC at the national level have given way to growing literature advocating the municipality as the most appropriate entity to test the validity of the theory [

11]. In this sense, Alesina et al. [

12] observe a longer budgetary cycle in smaller Italian municipalities linked to tax reductions, while Bonfatti and Forni [

8] qualify their existence in capital investments. In the same way, Chortareas et al. [

11] find the existence of political budget cycles through increased spending and excessive debt at Greek municipalities. These are particularly prevalent when mayors are running for re-election and are aligned with the central government. However, small Greek municipalities—with less than 10,000 inhabitants—do not have PBC. This is one of the reasons why we focus not on all municipalities but only on medium-sized cities. Finally, it is also significant that there is much more work on local PBCs looking at southern European countries than Nordic countries. We do not have data to infer whether this is a phenomenon that occurs more in the South, or simply that researchers in northern countries are less interested by the issue.

Naturally, the existence of political budget cycles at the local level is influenced by two variables that depend on higher levels: The presence of fiscal rules and of budgetary transfers. First, fiscal rules reduce the spending discretion of local governments, preventing them from incurring deficits or restricting the use of surpluses. Empirical evidence suggests that these rules limit political budget cycles [

8,

13].

Secondly, the financing of local governments through state transfers vs. own resources reinforces incentives to expand the size of the pre-election budget as demonstrated by Ferraresi [

14] in the case of Italian municipalities. Although municipalities are mostly financed through their own resources, transfers cause an indirect budget cycle [

15] and reinforce the fluctuation in the electoral cycle [

10]. Within the same scope, Garofalo et al. [

16] show that politicians at sub-state levels aligned with the presidential incumbent receive more funds from the central government and add that voters favor these candidates because they expect higher future transfers.

In the case of Spain, the studies conclude that raises in pre-election spending increase the likelihood of re-election of local governors. Balaguer-Coll and Brun-Martos [

17] found that increases in municipal public spending had a positive impact on the chances of re-election of local governments, and especially when this increase was made in the pre-election period at municipalities with more than 20,000 inhabitants, during the 2000–2007 period. This evidence is repeated for municipalities with more than 1000 inhabitants, and it is established that the increase in capital expenditure favors re-election [

18]. Furthermore, the likelihood of local politicians being re-elected is also a function of the length of time they have been in power [

19].

2.2. Local Expenditure in Culture

There is extensive literature analyzing the determinant factors of public expenditure at the local level, and the most recent findings indicate that it is mainly economic factors that explain them [

20], and that there is some mirroring effect between municipalities [

21]. Other works show that there is a range in the estimated elasticities with respect to free municipal income spanning from 0.98 for cultural schools to 2.70 for museums. The idea that cultural services are all stereotypical luxury goods with high income elasticities is, therefore, not a certainty, but most of the literature finds relatively high income elasticities for most cultural services [

22].

In OECD countries as a whole, the role of local governments in the provision of cultural goods and services varies greatly. Countries such as France or Ireland have central institutions dedicated to culture and the arts, each having the largest share of responsibility, and only delegating a small part to subnational levels of government. On the other hand, countries such as Austria, Belgium, and Germany have a more decentralized model, where a central ministry (Germany) may or may not exist, and where lower levels of government are responsible for most cultural matters. In order to size up the Spanish case, we should say that, in 2010, the year in which public funding for culture had not yet been disbursed, of the 6.8 billion euros allocated to Culture, 1.8 billion corresponded to the central government, 1.8 billion to the Autonomous Communities, and the remaining 4 billion was managed by local corporations. In other words, almost 50% of the cultural public budget was managed by local authorities. The arguments in favor of decentralization, in the area of fulfilling cultural rights, have to do with proximity to citizens’ needs, and it seems reasonable to conclude that it is at the local level that citizens’ cultural rights can best be identified and guaranteed, in a context characterized by great diversity of agents and preferences [

23].

Although it would seem reasonable that most cultural policies be enacted at the local level, it should also be noted that this is probably the level of administration where public spending on culture shows the highest level of inefficiency. The reasons are many and varied; lack of coordination and cooperation, overlapping and deficient dimensioning of infrastructures, competition for visibility, lo- quality information and limited intelligence available to policy makers [

23].

Indeed, for the Spanish case, one of the most important distortions to the efficiency of local spending on Culture comes from the fact that there is a perception, by local cultural politicians, that interventions in Culture have an electoral effect due to its potential ornamental character. Because of this perception, local cultural policy is subjected to the political cycle, accumulating greater inefficiency as a consequence of being too focused on improvisation, personal pet projects, and short-term vision, and on events with high media visibility but dubious transformative effects and impact [

24].

In their article on the relationship between culture expenditure and the PBC, Benito et al. [

25] defend the appropriateness of decision-making at the local level because politicians know better the cultural preferences of their voters and manage most of the culture budget. In similar terms, Getzner [

26] demonstrates the existence of political election cycles in Cultural expenditure for Austrian municipalities.

However, expenditure on Culture is not only a lever to win elections but a policy tool to transform territories, also in non-metropolitan and medium cities. Cultural activities can offer considerable development opportunities due to their potential to leverage local heritage and other resources, and give these areas competitive advantages [

27]. These findings are backed up by recent research led by the European Union that considers that cultural and creative industries “are in a strategic position to promote smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in all EU regions and cities” and, thus, “to foster the potential of culture for local, regional, national development and the spill-over effects on the wider economy” [

28].

So, to conclude, the aim of this work is to discover, in the first place, and for the Spanish case, whether spending on culture is subject to the political cycle, and whether it is so to a greater or lesser degree than the provision of other public merit goods (sports, education, and health). The second question will be, in reference to the political cycle, whether spending on culture has any real effect on the probability of being re-elected.

2.3. The Context of the Spanish Local Elections of 2015 and 2019

Since the establishment of the first democratic local councils in 1979, 12 municipal elections have taken place in Spain. The 2015 elections happened as the country was emerging from a devastating economic crisis and ending a cycle of severe austerity and depressed public spending, including at the local level. Additionally, an unprecedented protest movement, the so-called “15-M”, which appeared in 2011, crystalized into political structures outside the model of the two main traditional parties (social-democratic, PSOE, and conservative, PP) that had alternated in power until that moment in the young democratic history of Spain. In many Spanish towns and cities, various groups of voters and political platforms managed to overcome the two-party system that had been in place since the transition to democracy following the Franco dictatorship and, in this way, known social referents and activists became city mayors, such as was the case of Ada Colau in Barcelona, Manuela Carmena in Madrid, or Joan Ribó in València.

In this sense, the local elections of 2015 marked a departure from the trend of the conservative cycle with the triumph of candidates outside the main parties in cities as important as Madrid, Barcelona, València, or Zaragoza, among others. This was an unprecedented process in Spain, which would mark a turning point in contemporary politics. In a short span of time—the years between the two municipal elections—the traditional political groupings combined had lost over 4 million voters, with most of the votes going to the two emerging political parties. The 2019 elections, on the other hand, brought a certain disappointment with the processes of change and some cities (such as Madrid, Zaragoza, or Santiago de Compostela) returned to being governed by one of the two traditional parties. Although in 2019 there were already obvious signs of economic recovery and normalization, the elections came at a time of great political turmoil, which included the repetition of the general elections (for the government of the nation) and the hangover from the conflicts over the holding of a referendum of independence in Catalonia that was, ultimately, declared illegal. With this contextualization, we would like to emphasize that the two electoral processes were, for various reasons, relatively exceptional and far from what we would call “democratic routine”. In other words, periods in which, in the absence of other major political motivations, voters may have been sensitive to incentives provided by local public spending.

For all the above reasons we have limited our analysis to medium-sized cities, in order to try to reduce the weight of the major political trends on voters’ motivations

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Medium-Sized Cities

This article will focus on the analysis of the electoral behavior of medium-sized cities, as they are the settings where the effect of local administration on voting can be best appreciated. While in small towns those running for election and their personal contacts are a factor that can introduce a strong distorting effect, in large cities, supra-municipal political trends can exert more influence than strictly local ones, as the vote tends to be more partisan [

29].

Medium-sized cities are understood to be those with a population size of between 20,000 and 100,000 residents. Although higher limits can sometimes be found in the literature (e.g., [

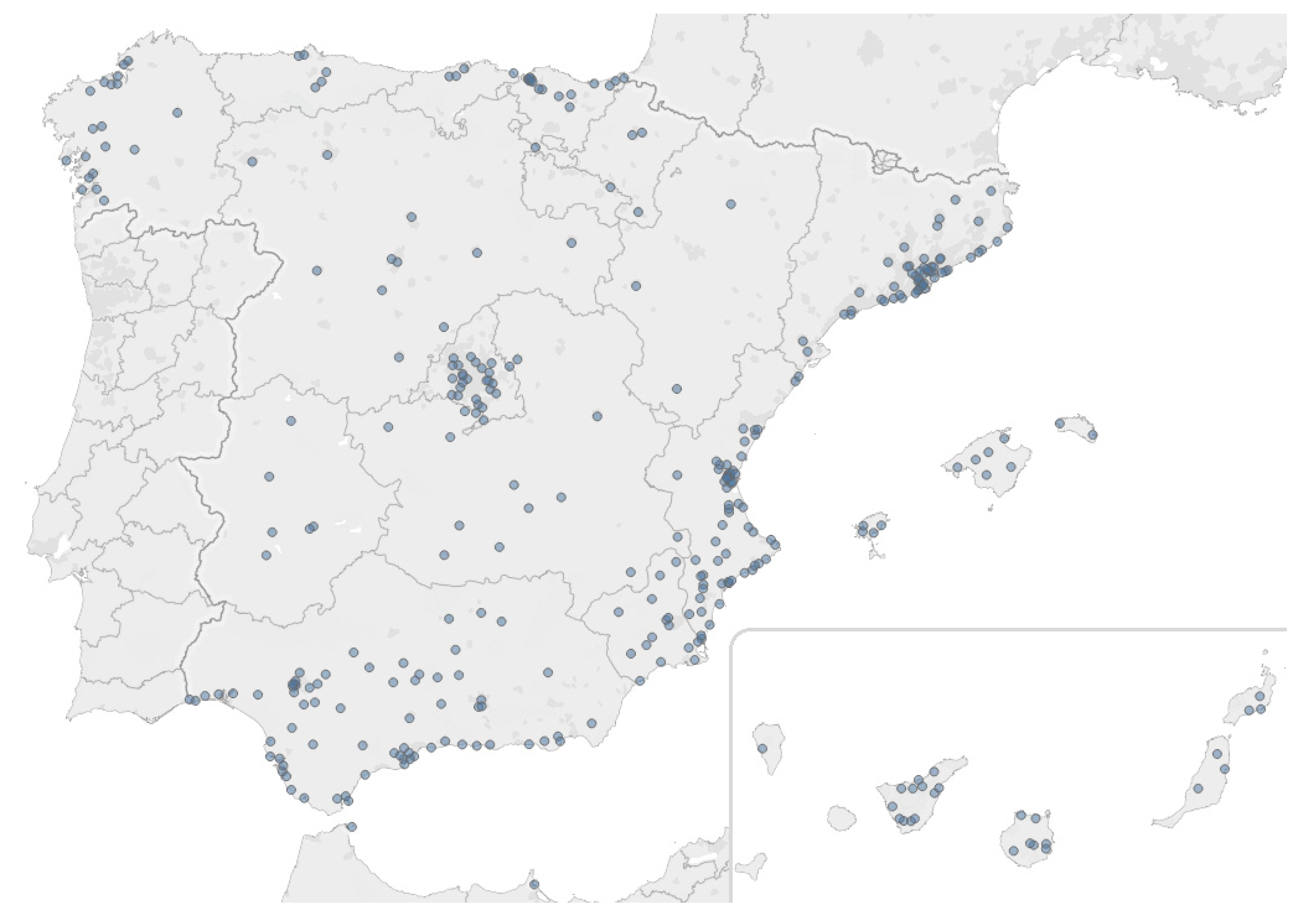

30], 50,000 to 500,000 residents), the extremely fragmented municipal distribution in Spain requires the employment of a more modest range. Of the 8131 municipalities in Spain, 61.5% have less than 1000 inhabitants, and 90.7%, less than 10,000. Only 63 cities exceed 100,000 inhabitants and only 6 would be above half a million, so it has been estimated that the interval of 20,000 to 100,000 residents is a fair representation of the concept of “medium-sized city” in Spain. This range encompasses 350 municipalities (2019 municipal register) with 13,841,094 inhabitants (29.4% of the Spanish population, as can be seen in

Table 1). Although there is no official statistical categorization of cities in Spain by size, this does exist in Germany and France (the latter is probably most comparable to Spain due to its similar fragmentation), with the same population criterion for the medium-sized cities as the one we have adopted here. This same principle has also been used in several studies, both for the Spanish case [

31,

32,

33] and for other countries (e.g., [

34], for Germany).

In terms of its geographical distribution, most of the medium-sized cities are located along the Mediterranean coast, the Canary Islands, and in the metropolitan area of big cities like Madrid, Barcelona, or València. To a lesser extent, there is also a certain concentration of medium-sized cities in Andalusia, Galicia, or the Basque Country, while further inland their presence is negligible, with the notable exception of the Madrid region (

Figure 1).

3.2. A First Exploratory Approach: Does the Electoral Cycle Influence the Budget in Culture?

The first step required for the analysis is to assess whether there is indeed electoral manipulation of budgets, with noticeable fluctuations in pre-election years. The evidence from the two electoral processes studied indicates that, in fact, this occurs both in the total budget and in the Culture budget in particular, as well as in the Sports budget. On the other hand, it is not overtly clear that the same occurs in Health or Education (especially if we consider changes in their relative weight within the total budget). In the case of culture and sports, not only does the per capita spending increase more in the last year of the legislature vis-à-vis previous years, but its relative participation in the budget as a whole does too.

In

Table 2, the year-on-year increases in expenditure per inhabitant in absolute terms for the first three years of the legislature (average) are compared to the pre-election year, for the average of medium-sized cities. In addition, we verify the percentage of cities that behave according to the electoral logic; that is, that raised expenditure in the last year of the legislature to a greater extent than in previous years or, for a similar outcome, cut it by less. The same analysis is repeated in terms of percentage point variation of the total budget, to see if the proportion of the municipal budget allocated to each of the merit goods changes in the pre-election year (

Table 3).

It is now possible to conclude what had already been advanced previously: That municipal budgets in medium-sized cities follow an electoral logic both in terms of the total budget and in terms of spending on culture, as well as in sports. This is not the case for health and education, since the visibility of its effects in the short term is lower and it is therefore more difficult to obtain immediate political returns.

In particular, 87% of medium-sized city councils increased their expenditure per capita on culture in 2014 (pre-election year) by more than they did in the three previous years, and 59.3% did the same in 2018. In 2014, city councils increased the per inhabitant expenditure on culture by an average of 2.94 euros, while in the first three years of the legislature they had reduced it, on average, by 10.32 euros per year. In 2018, the councils increased spending on culture per inhabitant by an average of 6.19 euros, while in previous years they increased it by only 2.19 euros. With regard to the relative weight of expenditure on culture within the total budget, 66.4% of medium-sized city councils also increased it more in 2014 than in previous years (in fact, what tended to happen was rather that the budget declined by less), and 52% in the case of the pre-election year of the following legislature.

Furthermore, municipal governments that followed this type of electoral behavior with the culture budget tended to experience greater electoral success than those that did not. In 2015, 52.5% of the municipalities that applied this behavior managed to revalidate their governments, in contrast to the 45.2% success rate of those that did not. In 2019, the success rate was 75.4% vs. 67.2%.

Therefore, it can be seen that (1) the majority of city councils did apply an electioneering behavior to cultural expenditure, as well as to the total budget, and the sports budget, and (2) governments that followed this trend experienced greater electoral success, which would seem to indicate that this is a relevant factor. Based on this first exploratory analysis, the research now turns to the matter of determining whether this does indeed have a significant impact.

3.3. Data for the Pooled Logit Model

Data have been collected from different official sources, and includes variables related to the local socio-demographic context, the municipal budget, and political indicators. More specifically, below are the variables used in the model, and their definitions.

Health. Increase in spending on health on a pre-election year, by percentage points on the total budget compared to the previous year. From the Ministry of Finance, 2013–2014 and 2017–2018.

Culture. Increase in spending on culture on a pre-election year, by percentage points on the total budget compared to the previous year. From the Ministry of Finance, 2013–2014 and 2017–2018.

Education. Increase in spending on education on a pre-election year, by percentage points on the total budget compared to the previous year. From the Ministry of Finance, 2013–2014 and 2017–2018.

Sports. Increase in spending on sports on a pre-election year, by percentage points on the total budget compared to the previous year. From the Ministry of Finance, 2013–2014 and 2017–2018.

Unemployment. Unemployment rate recorded by social security in January 2015 and 2019.

Participation. Percentage of electoral participation. From the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the 2015 and 2019 municipal elections.

HHI. Concentration/fragmentation of the council. Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) calculated with the seats of the parties represented in the council in the legislature prior to the election and divided by 10,000 to adjust the scale. A high value implies greater concentration into very few political parties. Based on the municipal election results obtained from the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the 2011–2015 and 2015–2019 legislatures. The assumption behind the inclusion of this variable is that the greater the political fragmentation, the less likely it is that incumbent governments remain in power for long periods.

Young. Percentage of the population between 15 and 29 years of age. From the municipal register on 1 January 2015 and 2019.

Older. Percentage of the population aged 65 or over. From the municipal register on 1 January 2015 and 2019.

Studies. Percentage of the population with higher education qualifications. Values correspond to the 2011 census, the last year for which data at municipal level is available (a census is carried out every 10 years).

Result. Dependent dichotomous variable that captures the election result. It is defined as success if the previous government retains power and as failure if it does not. Based on the municipal election results (2015 result with respect to 2011–2015 legislature and 2019 result with respect to 2015–2019 legislature) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Health, education, culture, and sports spending programs are those defined in local budgets as merit goods, and thus are the spending programs analyzed. All four constitute Area 3 of the municipal budgets (“Production of public merit goods”), according to Spanish legislation.

The inclusion of the age variables (Young and Older) aims to control possible generational behavior patterns when voting. We can presume a lower propensity to change among senior voters, while the variable Young would pick up the opposite effect, with a greater openness to change and, therefore, a lower propensity to facilitate re-election. These two age groups may also have different interests in the distribution of municipal spending. In the same way, people with higher education (Studies variable) may value municipal spending differently, and may also be more cautious and critical of the electoralist and opportunistic behavior of their rulers.

On the other hand, the unemployment rate is clearly a factor of dissatisfaction that can also be transferred into municipal politics. Likewise, the level of electoral participation may have logical consequences for the outcome of the election. Finally, the concentration or fragmentation of the municipal council (HHI) is an opposition’s indicator that the ruling party must confront in order to face re-election.

Although other variables, such as population, proportion of women, average income, public debt, ideology of the governing party, or total expenditure per inhabitant were initially collected, they were finally not applied to the model, and so are not explained in detail.

Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the model are displayed in

Table 4. Apart from these, it is important to see the data in context. In reference to the distribution of the budget, the percentage of expenditure on culture in the municipalities of the sample for the two pre-election years represents, on average, 6.02% (

s = 3.27%). This percentage is higher than that represented by the rest of the merit goods: Education 5.28% (

s = 3.17%); sports 5.15% (

s = 3.25%); and health 0.58% (

s = 1.05%). In euros per inhabitant, this means 54.2 in culture (

s = 30.4), followed by education (

= 47.1,

s = 31.4), sports (

= 45.9,

s = 32.2), and health (

= 5.32,

s = 10.2). In this last case, it must be borne in mind that municipal powers in Health are scarce and many city councils do not even have any expenditure on this program. Finally, the total budget represents, on average, 987 euros per inhabitant, with a standard deviation of 321 euros.

It is also necessary to better qualify other contextual variables. While the differences in electoral participation in 2015 and 2019 are irrelevant, average unemployment is much higher in 2015 ( = 0.275, s = 0.0953) than in 2019 ( = 0.198, s = 0.0837) due to the economic trends. It should be noted that these figures correspond to the ratio of registered unemployment (registered unemployed workers divided by the sum of said unemployed plus registered active workers), which throws higher figures than real unemployment, as estimated by the Labor Force Survey (EPA, by its acronym in Spanish), which unfortunately does not provide a breakdown of data at municipal level. The political cycle also manifests itself in the ideology of municipal governments. While, for the whole sample the proportion, it is fairly balanced (48.86% right-wing governments vs. 48.71% left-wing and 2.43% undefined), in the 2011–2015 legislature right-wing municipalities clearly predominated over left-wing ones (65.43% vs. 32.57%), while in the following legislature in 2015–2019 the proportion was practically reversed (32.29% vs. 64.86%).

3.4. Model

Since the dependent variable

Result is binary, the appropriate regression model to carry out our analysis is the logit regression model. Thus, we have applied a pooled logit model as a first approach to analyze the effects that certain expenditure variables on the production of merit public goods (health, education, culture, and sports) have on the probability of a governing party in a local corporation revalidating its mandate (variable result). Specifically, if

X is a vector of explanatory variables

that are observed in two time periods (

t = 1, 2) for a set of municipalities (

i = 1, 2, ...,

N = 350), the pooled model can be expressed as follows:

where

P is the conditioned hope of

Y (the probability of the council’s government being revalidated) given the values taken by the explanatory variables. However, since

P is not linear either in the

X’s or in the parameters

β, the model (1) is usually expressed in a linearized way as

4. Results

Initially, the effect on the re-election probability of the variables Health, Culture, Education, and Sports was analyzed depending on a given level of the variables Young, Older, and Studies. For this purpose, the effects of the interactions were introduced into the model. Since all the coefficients of the interaction effects were not significant, the estimated pooled model is:

For the model given in (3), we checked the linear relationship between the explanatory variables (which are all continuous) and the logit of the outcome. This was done visually representing the scatter diagrams between each predictor and the logit values. The graphs showed that all the variables correlated in a fairly linear way with the dependent variable (revalidation of the municipal government) on a logit scale. The possible existence of influencing values was then examined by examining Cook’s values. Three anomalous values were detected (observations 252, 283, 405, 485, and 617), but following the analysis of the standardized values of the waste it was possible to conclude that these outliers had no influence.

A multicollinearity diagnosis, with the package for R mctest [

35], was also carried out for the independent variables (see

Table 5). The results show that multicollinearity does not seem to be a problem in our study: The variance inflation factors (VIF) presented very low values and all of them under 10 [

36], with the

Young and

Older variables presenting the highest VIF (1.4237 and 1.3874, respectively). Nor was multicollinearity detected on the basis of the condition number.

The results of the fit tests seem to validate the model, with a very significant likelihood ratio (LR) , which indicates that it is well fitted. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test has a p-value of 0.8159, showing that the model is adequate.

As in the logit model the coefficients of the parameters have no direct interpretation, the marginal effects have been calculated using the mfx package for R [

37]. The average marginal effects of the sample are shown in

Table 6. Robust standard errors have been calculated to take into account non-observed heterogeneity in the pooled model.

As can be seen in

Table 6, the variations in cultural expenditure during the year prior to the elections have a significant effect (although significant at 10%) on the probability of winning re-election, while the remaining variations in the provision of other public merit goods do not. Neither does spending on sports, which, as has been seen, was also manipulated electorally, apparently without delivering a return. Although not significant, the negative impact of healthcare spending should also be highlighted, which could be interpreted to mean that those benefiting from the variation in healthcare spending are groups with less influence on the election results (populations with lower income levels and, probably, lower voter participation). It should be noted that local health expenditure is a very small part of the total health budget, which in Spain is largely the responsibility of regional governments.

The coefficient representing the marginal effect of cultural expenditure is the highest of all coefficients for all other variables and is quite substantial in absolute terms. Supposing that spending on culture in a pre-election year is increased by a third in percentage points on the total budget compared to the previous year (for example progressing from 6% to 8%), this would improve the probability of being elected by almost 10%. Since the proportion of the budget devoted to culture is relatively small (around 5%), it could be inferred that spending on culture is a relatively cost-effective way to buy the favor of voters.

The rest of the variables that have significant effects on the probability of failing to be re-elected are: Firstly, the unemployment rate in the election year, which can be interpreted as the voter perceiving the responsibility of local politicians in the employment levels; secondly, the degree of participation in the election. This result could be interpreted as voters being more mobilized by rejection (of a certain party or candidate) than by adhesion and, consequently, where a candidate is strongly rejected the levels of participation increase and, conversely, the probability of re-election is reduced.

Thus, all other factors remaining constant, an increase in unemployment and participation significantly reduces the probability of revalidating the municipal government. An increase of one percentage point in the unemployment rate decreases the probability of revalidating the municipal government by approximately 0.77%, and an increase of one point in participation reduces it by 1.26%.

The proportion of over 65s in the population is also a significant variable and, the higher this proportion, the greater the probability of re-election of the incumbent government, which could be attributed to a lower propensity to change among senior voters. An increase of one percentage point in the population of over 65s increases the probability of re-election by 1.16%. The rest of the socio-demographic variables are not particularly significant.

Nor is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) of political party concentration statistically significant. Nevertheless, the sign of the coefficient of this variable behaves in accordance to the hypotheses expressed, that is, it positively influences the probability of repeating the electoral result as there is less competition from the opposition.

5. Discussion

Despite the fact that the Spanish constitution reserves certain exclusive competences in the field of culture to the central government and the autonomous communities (regional governments), the response of local governments has consolidated as a reality, where the main source of public funding for cultural activities comes from the local sphere. Local governments provide a wide range of cultural services and facilities such as auditoriums, theatres, cultural centers, archives, museums, non-formal and lifelong artistic learning, festivals and regular programs for music, cinema, performing arts, literature, crafts, provision of spaces for the development of community culture, and centers for the conservation, interpretation, and socialization of historical, natural, and artistic heritage.

The results are quite consistent with those obtained previously [

25] for the municipalities of the Murcia region, where results revealed that city mayors adopt an opportunistic strategy, increasing cultural spending in election years and reducing it in the second year after the election, which fits in with the hypotheses considered.

We can launch some hypotheses about why culture is a public expense that generates more electoral impact than others. Firstly, from the point of view of the impact on the population, it is an expense that has a high visibility at a relatively low cost, since the programmed cultural events have repercussions in the media and are part of the social relations in medium-sized cities. Secondly, it is an expenditure that usually allows for greater discretion in its execution, since there is much less planning tradition in the field of culture than in other areas of public policy. Thirdly, it generates less opposition both because of its modest size in proportion to the total expenditure and because culture is established in spaces on the periphery of struggles for local power, which is more likely to be in areas related to urban planning or economic promotion.

It is clear that the results obtained here are important and have major implications for the articulation of local cultural policies. Today we are aware of the impact that creativity, the arts, and culture have on us [

38], from experiences and values, cognitively, aesthetically, or spiritually; to transforming our individual, social, civic, economic, or political dimension, influencing our sense of belonging, of identity, of building our social capital; to nourishing the knowledge that gives us autonomy, reinforcing our capacity to look critically at our environment; to shape our sensitivity and the capacity to obtain value from aesthetic enjoyment; to amplify our expressive and communicative capacities. That is, to realize our cultural rights to be ourselves, participate, and communicate, promoting values and innovative processes for individual and social development, expanding the degree of personal freedom, and reinforcing our democracy and dignity. In short, cultural dynamics are central [

39] to reorienting urban development models towards fairer and more sustainable scenarios in the mid-term. Their capacity to influence aspects such as the production and consumption models, lifestyles, and forms of work organization [

40] determines their potential for innovation, disruption, and creativity.

However, it is also known, from scientific evidence [

41], that the size of the cultural and creative sectors has causal effects on productivity, innovation propensity, humanization, and adaptation of the technological model, the health and wellbeing of citizens and their commitment to shared values, and the resilience and capacity for growth of an economic system.

Today, the combination of creativity and memory as resources, digitalization as a process to be intensified, and sustainability as the final objective, have become the driving force behind the development of a circular, experiential, collaborative, and more egalitarian economy.

Cultural and creative sectors are among the hardest hit by the pandemic, and they need short-term support, but local policies can also leverage the economic and social impacts of culture in their broader recovery packages and efforts to transform local economies. This is not the time to suffer the effects of opportunistic attitudes from local politicians and it is necessary to convey the idea of more responsible behavior for activities that also spur innovation across the economy, as well as contribute to numerous other channels for positive social impact (wellbeing and health, education, inclusion, urban regeneration, etc.).

Given the importance of culture and creativity in our societies, it is hardly surprising to discover that they can be instrumentalized in pursuit of political gain, which has the unfortunate consequence of corrupting their intrinsic objectives. Their proven electoral value and their subjugation to the political cycle can lead to inefficiencies in their articulation and diminished effectiveness in achieving their main objectives.

Paradoxically, experience has shown that cultural policies have a high degree of autonomy and limited political power [

24,

42]. This assumption is justified by an argument that has a certain empirical justification: The amount of power held by the person responsible for culture (measured in budgetary terms) is relatively modest compared to other budget items. This assertion is consistent with the empirical evidence that cultural departments are more often led by “independents” than other areas of public management. It is also consistent with the fact that political disputes (such as during election campaigns) rarely revolve around issues of cultural policy. Clearly, other issues are also relevant. Even so, we have seen that local cultural policy has a significant effect on the probability of re-election at local government level, giving it greater relative power.

However, the results of this research should be considered with caution. First of all, this study refers exclusively to medium-sized municipalities (between 20,000 and 100,000 inhabitants), which in the Spanish case only includes about 30% of the total population. The study should be expanded to include the rest of the population to see if the conclusions are also applicable, although we intuitively suspect that the phenomenon may be specific to medium-sized cities.

Secondly, the methodology applied in this work presents a series of limitations: By pooling the different municipalities in the two time periods considered, we consciously disregard the heterogeneity that exists among different municipalities. However, given that there is only one panel with two time periods, a fixed-effects model is unlikely to capture this potential heterogeneity either. The availability of a panel with a greater number of time periods would allow a more detailed study to be carried out.

From the results obtained, we can highlight three fundamental aspects. Firstly, the evident temptation for mayors to design cultural policies in an ornamental vein (banal entertainment) in electoral times. Secondly, the growing opportunity cost that these practices entail given the current evidence of the impact of culture on development dynamics. Thirdly, the need arising from the two previous issues in terms of monitoring (accountability) and strategic planning in local cultural policy. Now more than ever good local governance in culture is crucial. In any case, the verification of our hypotheses presents an interesting scenario for the design and management of public cultural policies and projects. The centrality of these projects in facing current municipal development challenges also adds to a context of singular interest for the regional political agenda.