Abstract

This article seeks to forecast the short- and medium-term impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the cultural and creative ecosystems of the 81 cities in Spain with between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants. Data on employment in nine sectors (per NACE Rev. 2) support the characterization of cultural ecosystems based on their dynamism, specialization, and propensity to form clusters (thanks to the co-location of certain sectors, meant to generate inter-sectoral spillovers and cross-sector synergies). The applied methodology consists of comparing these three attributes during and following the 2008 financial crisis. Then, any changes observed are interpreted in light of arguments from the COVID-19 literature, and from our own analysis, in order to assess the probability of recurrence (or nonrecurrence) during the current pandemic. Throughout this process, the metropolitan or non-metropolitan position of cities is taken into consideration. A first conclusion is that, as in the financial crisis, the behavior of ecosystems during the pandemic will be asymmetric. Secondly, metropolitan and non-metropolitan cities will maintain their distinctive sectoral specializations. Non-metropolitan cities appear to be more vulnerable for their strong connection to creative sectors most affected by the pandemic, although some can take advantage of good cultural supply and proximity to metropolitan centers. Metropolitan cities seem more secure, thanks to the higher presence of less vulnerable sectors (due to elevated and accelerating digitization). Nevertheless, most functional clusters were diminished during the financial crisis, and it seems unlikely that sectoral co-locations will re-emerge in a post-pandemic scenario as a business strategy, at least in the short term. Beyond these forecasts, we recommend dealing with certain structural failures of these ecosystems, especially the vulnerability and precariousness of most cultural and creative companies and workers.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, most national and international organizations have warned of the negative impact that the health crisis could have on cultural and creative activities. Indeed, this pandemic and the measures taken to minimize its impact, most notably the prolonged confinement of populations and reductions in the use of public spaces and cultural venues, have often led to drastic declines and even total losses of income for cultural and creative enterprises. The lockdown measures forced a general halt in production, the closure of cinemas, and the cancellation of festivals, film fairs, and markets. The cultural and creative sectors were among the first to lock down and will be among the last to reopen [1].

Certain sectors of cultural activity such as museums, libraries, or public theaters have benefited from institutional aid, but this has not prevented the majority from facing significant budget deficits. With regard to the remaining sectors, in particular small companies and the independent professionals (freelancers) that comprise them, the clear risk of bankruptcy [2] is still present, due to delays in promised aid and new outbreaks of the disease, which keep production and programed activities from resumption.

The possibility of near-total bankruptcy for a large part of the cultural sector is, in some cities, a disturbing prospect, from an economic as well as a socio-cultural perspective, insofar as this sector is largely noted for constituting part of the local identity and quality of life [3] and for its contribution to urban development and the well-being of the population [4,5,6,7]. For this reason, culture and especially cultural capital has been for years included among the essential components of what has been called ”comprehensive wealth” [4,8]. Important public actors often defend these ideas. Tibor Navracsis, EU Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport, has remarked that culture and creativity represent “powerful tools to bring people closer together, build a sense of community, and encourage citizens to be active members of society” [9] (p. 7). Leaving behind the most fragile aspects of this sector could cause irreparable economic and social damage, and therefore the challenge has become to develop inclusive and sustainable creative economies [10] that can alleviate the negative impacts of COVID-19 in the short term and help to identify new medium-term opportunities for numerous public, private, and nonprofit actors involved in cultural and creative production [2].

With the aim of making a useful contribution from our disciplines (human geography and economics) and areas of research specialization (geography, economics, and local impacts of culture and creativity), we focus our attention in this article on the cultural and creative ecosystems of medium-sized cities, in order to assess the impacts leveled against them by the prior economic crisis and to establish possible scenarios for the current one, derived from the ongoing state of alarm. We do this while assuming the ”ecological” nature of cultural and creative activities developed in (these) cities, in the sense that they operate through interconnections and interdependencies of resources of various types [10,11,12]. We also take into consideration that the ecosystems of these medium-sized cities have scored very positively in recent evaluations of their cultural and creative performance [9,13]. Additionally, as found by Barrado et al. in a previous research by members of this group on medium-sized Spanish cities, these are specialized ecosystems, although specializations differ depending on a city’s metropolitan or non-metropolitan location [13,14,15]. It has also been detected that cultural companies and jobs in these ecosystems belong to diverse sectors [16,17], making it possible to demonstrate that the formation of hubs, or functional clusters, is not exclusive to large cities [11]. However, as is typical in this sector, most ecosystems comprise high proportions of small companies and non-standard forms of work [2,18,19].

In this work, we propose to answer the following questions:

- (1)

- How might the coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath ultimately affect the behavior of the cultural and creative ecosystems in medium-sized cities?

- (2)

- How might the pandemic alter cultural and creative specializations in their ecosystems?

- (3)

- What expectations does the pandemic raise in ecosystems in terms of functional clustering?

These three questions seem relevant to the extent that they refer to facets that are expressive of the strength of those ecosystems; it has been shown that cities which perform better in cultural and creative activities also enjoy better socioeconomic performance [20,21,22]. As an object of analysis, we have selected the cultural and creative ecosystems of 81 Spanish cities with between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants, along with data pertaining to nine different cultural and creative sectors. First, we carry out a systematic comparison of the dynamics, specializations, and levels of clustering of these ecosystems in the years 2012 and 2018 (considered expressive of the peak and final years of the financial crisis). Next, we seek to establish the impacts that the current pandemic might conceivably generate on the same three aspects, given the changes observed during the recent financial crisis, the consideration of trends pointed out by various authors in relation to the current pandemic, and empirical evaluation of the exposure of ecosystems to certain risks and opportunities highlighted in the literature. This strategy seems appropriate because, although the two crises stem from different causes, some of their effects are similar such as austerity and budget cuts, unemployment, and falling demand [23]. In addition, crises tend to develop along pre-existing channels, revealing structural weaknesses that have been obscured and perpetuated by short-term policies employed to face prior global crises [18].

The analysis undertaken leads us to obtain the following results:

- (a)

- In the short term, the pandemic will have effects that are differentiated according to sectors and cities.

- (b)

- In the medium term, the cultural and creative ecosystems of medium-sized cities will maintain their characteristic specializations, which might result in risks or opportunities, depending on the particular specialization.

- (c)

- In the long term, effects will tend toward the consolidation of more structured and inclusive cultural ecosystems.

These forecasts strike us as interesting for several reasons. In the first place, we confirm asymmetrical impacts from the pandemic in the cities studied, according to the nature of their cultural and creative ecosystems. Second, we show how the cultural dynamics of the ecosystems in a post-pandemic scenario will continue to be associated with particular geographical contexts, most specifically in terms of their metropolitan or non-metropolitan location. Third, we insist on the necessity of inclusive and sustainable cultural policies aimed at promoting the types of institutional and professional change, also considered necessary by various authors for a post-COVID-19 era [2,10,24]. Finally, it should be noted that this work improves the knowledge on the geography of cultural and creative activities in medium-sized cities, generally marginalized by research focused on large cities.

The structure of the paper is as follows: In Section 2, we present our postulates on the nature of these ecosystems and the impact of the two recent crises, financial, and health; in Section 3, the methods employed are described, the empirical materials are presented, and the cities under study are introduced, with explanations of determinations made for establishing levels of specialization and clustering in their cultural ecosystems, as well as their prospects during the pandemic, and the impact-risk indexes prepared from our own unpublished indicators are also explained; Section 4 contains the results of our analysis of the dynamics, specializations, and clustering of the cultural ecosystems studied during the financial crisis, along with our forecasts on the impacts of the pandemic around the same three aspects; the text ends with some prospective considerations, including the likelihood that the pandemic may permit the identification and pursuit of new opportunities, in order to move creative economies toward a more inclusive and sustainable future [10].

2. Theoretical Framework and Background Information

2.1. The Nature of Cultural and Creative Ecosystems in Medium-Sized Cities and Their Attributes of Specialization and Clustering

The ecological or systemic nature of creative and cultural activities in cities is implicit in the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor [25], a tool recently devised (2017) by the European Commission to evaluate the performance of cities through the synthesis of 29 descriptive indicators of nine relevant areas or dimensions. Dimensions range from those related to ”cultural vibrancy”, referring to the local cultural supply and the demand it generates [26], to those that express the weight of the ”creative economy” through reciprocal relationships between culture and creativity (on the one hand) and the urban economy (on the other hand), in terms of jobs and innovation [27], to other indicators concerning the ”enabling environment” formed by requirements favoring the development of cultural places and their economies.

The specialization conferred by the significant concentration of companies and jobs in some specific sectors and phases of the production chain [13] is a common attribute of ecosystems in medium-sized cities [15,28]. For this work, it is important to consider that such specialization may differ if the cities considered are metropolitan or not [6,16,17]. The concept of ”borrowed size”, coined by Alonso to explain how the cities that make up large metropolitan complexes “have access to agglomeration benefits of larger neighboring cities” [29,30], favors the specialization of metropolitan ecosystems in sectors that benefit from economies of agglomeration, such as printing or architecture, or those linked to audiovisual and digital culture. The non-metropolitan cities, for their part, enjoy the aspect of ”centrality”, i.e., a Christallerian concept that foresees for these cities a greater provision of services due to the wider markets they serve. This centrality is enhanced when cities also perform functions as territorial capitals, with a disproportionate presence of public sector activity. Therefore, non-metropolitan ecosystems typically specialize in sectors demanded by the public sector for institutional activities (graphic industries, computer activities, press, and advertising), as well as in the performing arts sector, the crafts sector, and those linked to the management of heritage [14,15,31].

Clustering supposes that cultural companies and employment within ecosystems belong to different sectors, together forming functional clusters or hubs [16,17]. According to Lazzeretti et al. [32], this phenomenon has been attributed to an ability of firms, especially in nontraditional creative sectors (audiovisual, programing, advertising and promotion, and other professional activities), to gain from inter-sectoral spillovers, as well as serendipitous cross-sector synergies, the so-called ”urbanization economies” [33]. The affinities between nontraditional sectors lead to colocalization, including with traditional creative sectors such as the performing arts. In any case, this is a very significant attribute of ecosystems, since these clusters are associated with high rates of innovation and economic growth [4,15,28,31]. In relation to the typical co-location of ”nontraditional” sectors, it should be taken into account that such sectors are immersed in frequent changes to their business models, through the improvement of their connections with global production chains and a generalized trend in digitization [6,7,34,35], which will undoubtedly affect their locational strategies.

2.2. Considerations on the Impact of Crises (Financial and Health) on Cultural and Creative Ecosystems

Despite their distinct origins, the 2008 crisis and the pandemic are similar in having generated unemployment and drops in demand in the cultural sector, as well as similar reactions of states and governments [2,19,23]. Additionally, asymmetric behavior of the cultural and creative sectors has been observed in both crises. Forecasts advanced at the beginning of the financial crisis predicted job losses and business closures in activities selling services or goods to other creative or non-creative sectors [33]. Nevertheless, the direst of outlooks were not fully met, while some sectors performed better than expected [19,33]. In the case of COVID-19, estimated data for the USA [36], up to July 2020, already showed a disproportionate incidence of the pandemic in the performing arts sector, with job and income losses of 50% and 27%, respectively. With regard to the European Union, extraordinary job losses have been likewise confirmed in the performing arts and, more generally, in all sectors requiring travel and physical presence [24]. The asymmetric impact of the pandemic on the cultural and creative sectors is of particular interest, making possible an explanation (in the case of the financial crisis) and a prediction (in the case of the pandemic) of specific behaviors in cities and regions according to the preferential sectoral linkages of their ecosystems.

During the financial crisis, according to Montalto et al. [24], the better performance of some sectors was attributed to demand for culture remaining strong despite a tightening of family budgets, indicating that “culture and arts are resilient components of advanced economies’ activities, rather than being merely ‘frills’” [33] (p. 26). In relation to the pandemic, the situation is more nuanced, i.e., the need for social distancing, and its effect on venue-based sectors; the greater demand for digital solutions or online content, which could benefit sectors and platforms offering products and services of that type; the greater or lesser necessity of the good or service produced, and possible changes in the habits of consumers of cultural goods that might take place during months of confinement; or the degree of physical attendance that provision of the good or cultural service requires [2,24].

The literature on the impact of the financial crisis on the specialization of ecosystems is scant. Only limited evidence provided by a few authors during that crisis pointed to the persistence of regional differences in the way creative industries began to resurface [33]. According to this argument, the ecosystems of medium-sized cities, whether integrated into metropolitan areas or not, should have maintained their differences of specialization during the financial crisis. Therefore, our hypothesis is that they might be expected to do likewise post pandemic. In offering this hypothesis, we base our expectation on the validity for some cities of the effects of ”borrowed size” and ”centrality” explained above.

Regarding the impacts of the two crises, financial and health, on the clustering of ecosystems, a triumphant rise was observed during the former in new and digital economies, both from the supply side (facilitating the decentralization of productive creation) and from the demand side (making digital cultural content increasingly global) [2,35]. Specifically, the generalized digitization of certain sectors, the arrival of large multinational platforms, the possibility of users to upload cultural content that could be commercially exploited, the growth of video game developers and publishers, and the increase in production of video games were significant developments already underway on the eve of the pandemic. We shall examine the effects of such processes on the ecosystems studied here. Meanwhile, various authors coincide in pointing out that the pandemic constitutes an occasion to establish more structured, dense, and inclusive cultural ecosystems [2,18]. Demand for this would be justified, as the pandemic has revealed failures in the sustainability of creative economies. The creative industries tend to consist of relatively small and even micro enterprises, more vulnerable to short-term demand fluctuations and without easy access to finance [33]. One can certainly appreciate, both in the large losses of jobs during the pandemic [2,36,37] and in those of the financial crisis [19,33], the effects of high structural fragmentation typical of some sectors composed of flexible production networks and diverse labor structures [38]. Indeed, according to Montalto et al. [24], 32% of workers in the European Union in the area of culture are self-employed, a value much higher than the overall average (14%). It is also worth mentioning the interrelationships inherent to these sectors, which often sell their products (goods or services) to other creative sectors with similar characteristics. All of this would justify what has been described as the domino effect of the pandemic on the economy of cultural production chains [37], although the high fragmentation and informal nature of many activities make it difficult to specify the scope of that effect and to quantify the total losses suffered [24]. Likewise, the size of companies can be decisive when designing innovative projects, or when limiting their ability to participate in initiatives that can attract the extraordinary resources that recovery plans will make available. (The preparation of this work coincides with the publication of a new initiative, REACT-EU, set to complement the cohesion aid to member states through a budget of 55 billion euro, to be made available to diverse sectors from tourism to culture. Nor should we lose sight of options that the cultural sector may enjoy if able to link itself to proposals of regional priority, such as digitization or ”Green Europe”).

The data, here, represent a good example of the need to strengthen firms in the cultural and creative sectors, driving structural changes within sectors and in the conditions for their workers. Additionally, new medium-term opportunities for the numerous public as well as private and nonprofit actors involved in cultural and creative production need to be identified [2]. As one possible measure, various authors recommend taking advantage of the fact that the ecosystems of many medium-sized cities enjoy high densities of resources and of cultural places per inhabitant. These resources could ostensibly support the development of tourism and cultural proximity services, focused on the immediate environment, as well as on other cities and regions. With this approach, it would be possible to compensate for losses of visitors from other sources, and innovations would be stimulated that would favor the competitiveness of ecosystems in the medium and long terms [2,24].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Cultural and Creative Ecosystems: Cities, Sectors, and Data for Analysis

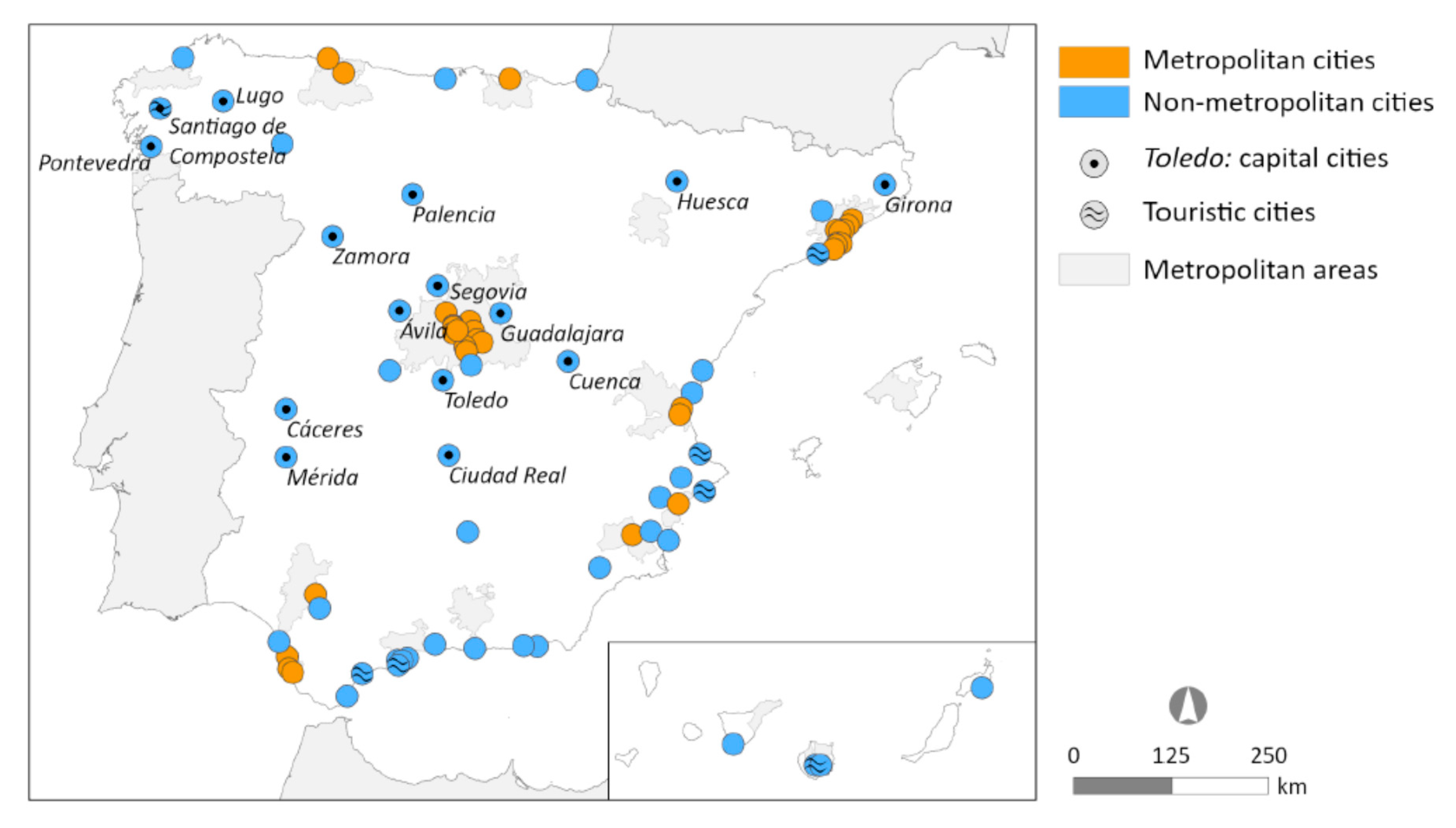

The 81 Spanish cities with populations between 50,000 and 100,000 comprise a very heterogeneous group, demographically as well as in socioeconomic terms (income and unemployment) and geographic location (whether they serve as a regional or provincial capital (15 of the total sample) or as a tourist destination, inland, or coastal (22 total)), as reflected in Table 1. Among these, are seven cities that have been declared by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites (Santiago de Compostela, Segovia, Ávila, Toledo, Cuenca, Cáceres, and Mérida), along with well-known tourist destinations on the Mediterranean coast (Estepona, Fuengirola, and Benidorm) and Canary Islands (San Bartolomé de Tirajana).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cities studied (2019).

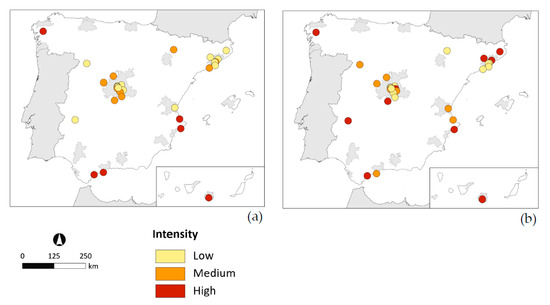

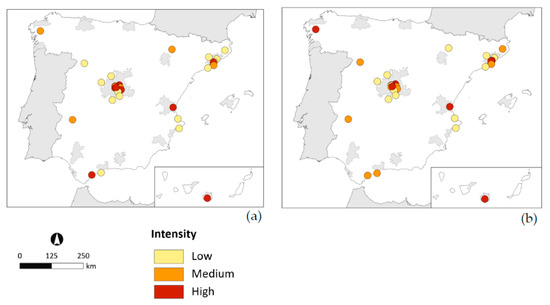

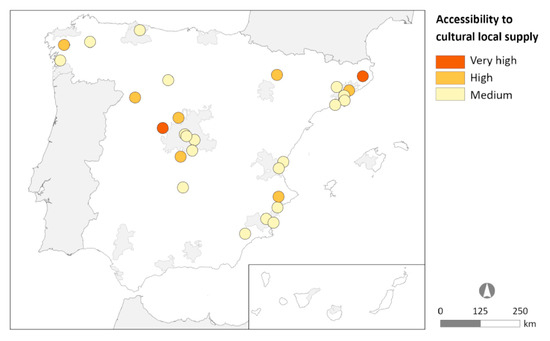

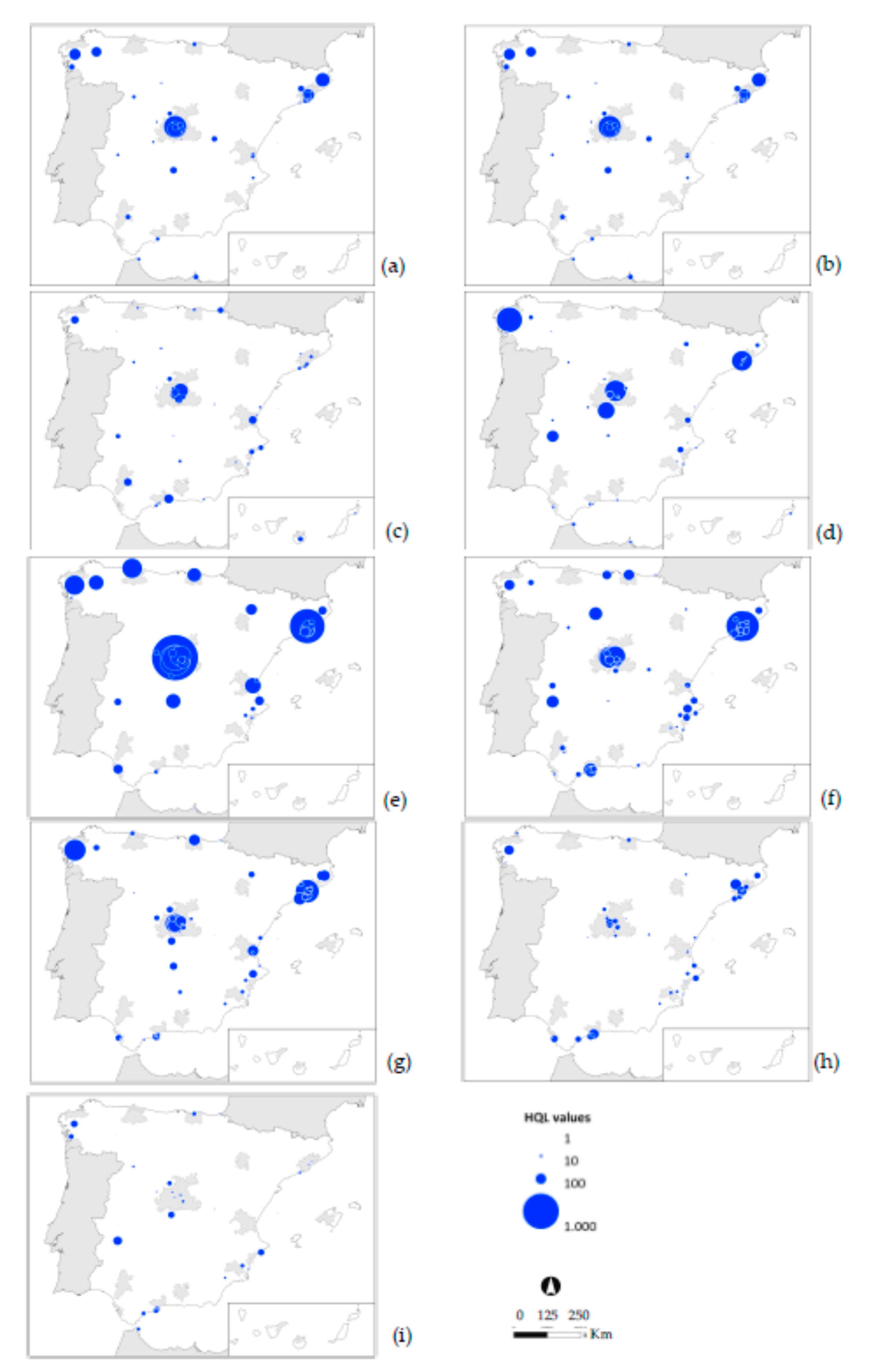

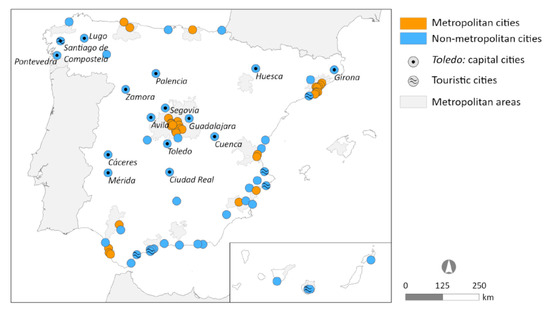

Among the geographical factors that need highlighting is whether a city is located within or outside of any of the 15 main metropolitan areas of the country (these fifteen areas are Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Sevilla, Bilbao, Málaga, Zaragoza, Palma de Mallorca, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Murcia, Alicante, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Vigo, La Coruña, and Oviedo-Gijón), this being a significant factor for the configuration of cultural ecosystems in this urban model, according to the scientific literature [13]. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, within the 81 cities, we find 32 integrated into metropolitan areas, while 49 cities are located outside metropolitan reach, in areas of low demographic density.

Figure 1.

Locations of the cities studied. Source, authors’ own elaboration.

In order to establish a profile for these 81 ecosystems, we have selected nine cultural and creative activities or sectors, all of which are included in the Satellite Account on Culture in Spain (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2008). These activities and their headings, according to the European Classification of Economic Activities of the European Community (NACE Rev. 2), are collected in Table 2.

Table 2.

Codes and cultural and creative activities analyzed in the study.

This selection roughly coincides with that adopted in numerous investigations on the geography of the cultural and creative sectors [34,36]. Nevertheless, when interpreting the initial data and the results, it is necessary to take into account that information from NACE is deficient in measuring artisanal and cultural activities, as well as those linked to cultural infrastructure and to public agencies relevant to the creation and consumption of culture. For each of the nine sectors we have obtained employment data provided by “Afiliados en alta a la Seguridad Social” statistics (Ministry of Labor and Social Security). The chosen variable includes total employment in each sector, whether salaried employed or self-employed. The city to which the jobs are assigned is the place of residence of the workers, and not necessarily that of the companies in which they work. The data has here been collected for the years 2012 and 2018, in order to identify any changes in the specializations of the cultural and creative ecosystems of cities during the financial crisis, and to enable the detection of trends that may continue through the pandemic and subsequent years.

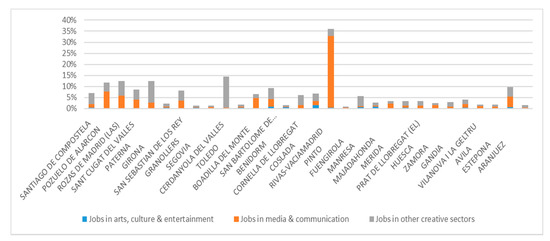

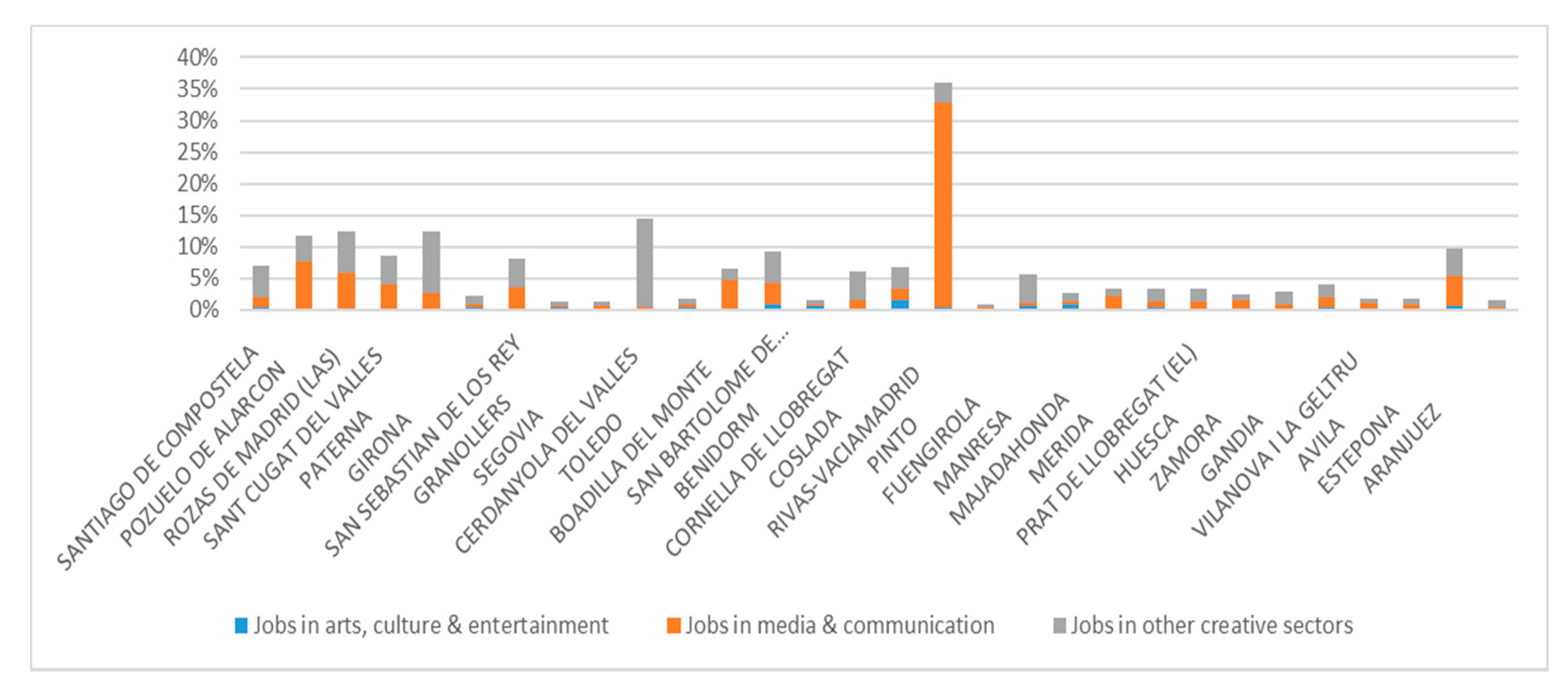

We have also handled data from six indicators obtained by our team [21,22] among the 29 proposed by the European Union in the aforementioned Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor tool [9,20]. (The weighted sum of the 29 indicators provides the C3 index that synthesizes the cultural and creative performance of the cities considered). These indicators, which refer to the year 2019, are as follow: indicator 10 (jobs in arts, culture and entertainment); 6 (tourist overnight stays); 11 (jobs in media and communication); 12 (number of jobs in professional, scientific and technical, administrative, and support service activities such as architecture, advertising, design, and photographic activities), D1.1 (synthetic index of Cultural Venues and Facilities); and 27 (potential road accessibility). Indicators 10, 11, and 12 are derived from the aforementioned “Afiliados en alta a la Seguridad Social”, which provides these statistics with 100% coverage. Indicator 6 has been obtained from official figures (Eurostat, National Statistics Institute) in 76% of the cases, and imputed in the others. (Missing values in the variable were replaced after classifying the 81 cities according to their size and tourist character (yes/no)) and assigning to the cities without data the median of the value of the variable in that group. The data on cultural venues and facilities (sights and landmarks, museums, cinemas, concert halls, theaters) came from TripAdvisor and a professional source (Association for Media Research), which allow 100% coverage. Finally, the indicator on accessibility has been obtained through a geographic information system from the public databases on population and infrastructures in 2019, incorporated into the server of the National Geographic Institute.

In order to assesses the level of vulnerability of the companies included in the 81 ecosystems, we have managed information from the Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos (Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System) database, the only accessible Spanish database that offers accounting and financial information disaggregated by both municipalities and branches of activity. This source allows us to complete an expressive sketch based on the size of companies in terms of employment, with information on the assets, operating income, and economic profitability of 5357 companies from the 81 cities in the indicated sectors.

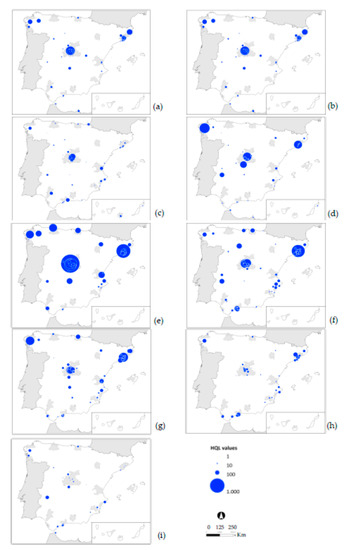

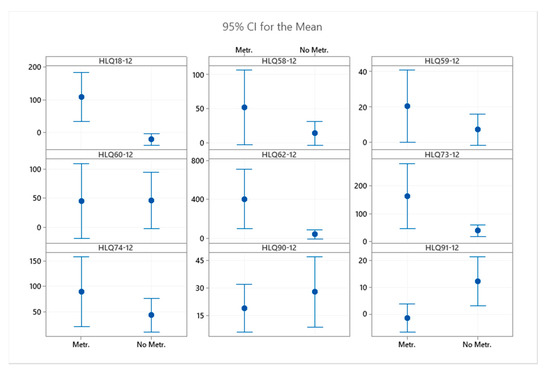

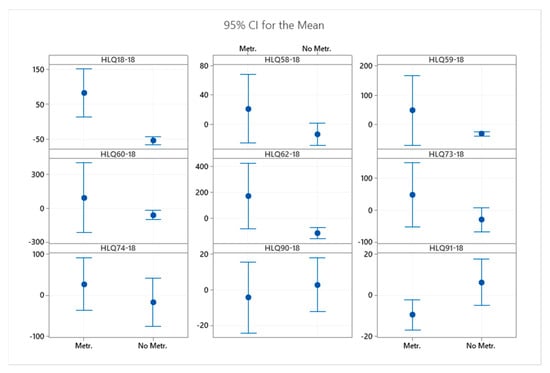

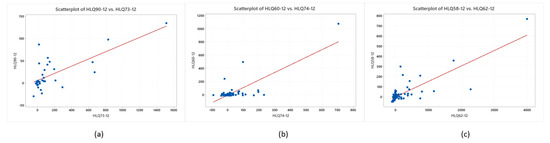

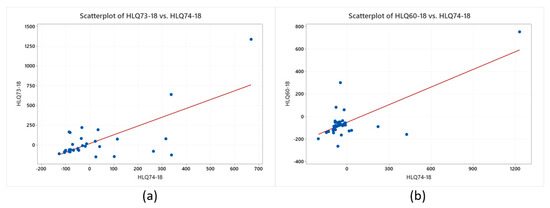

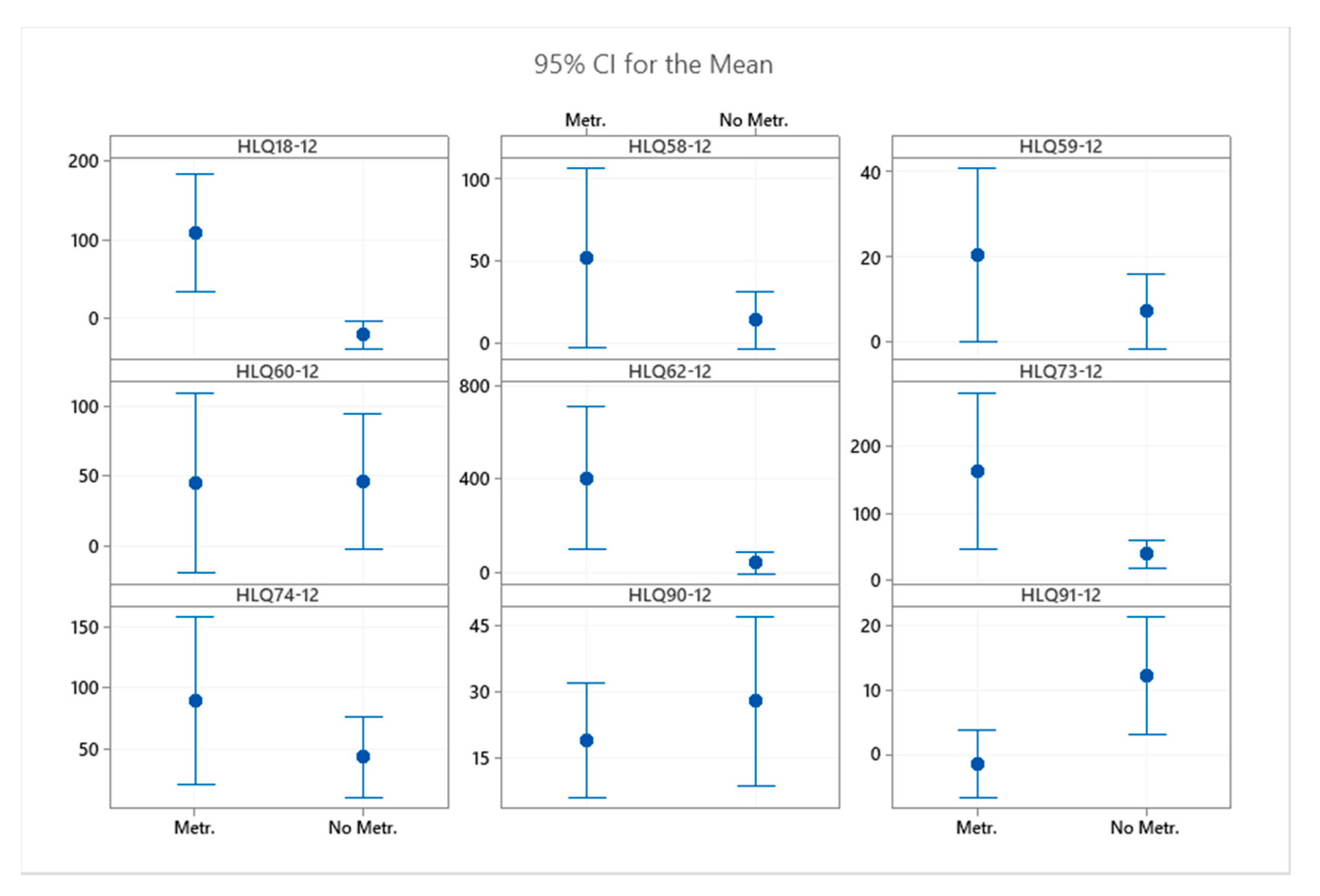

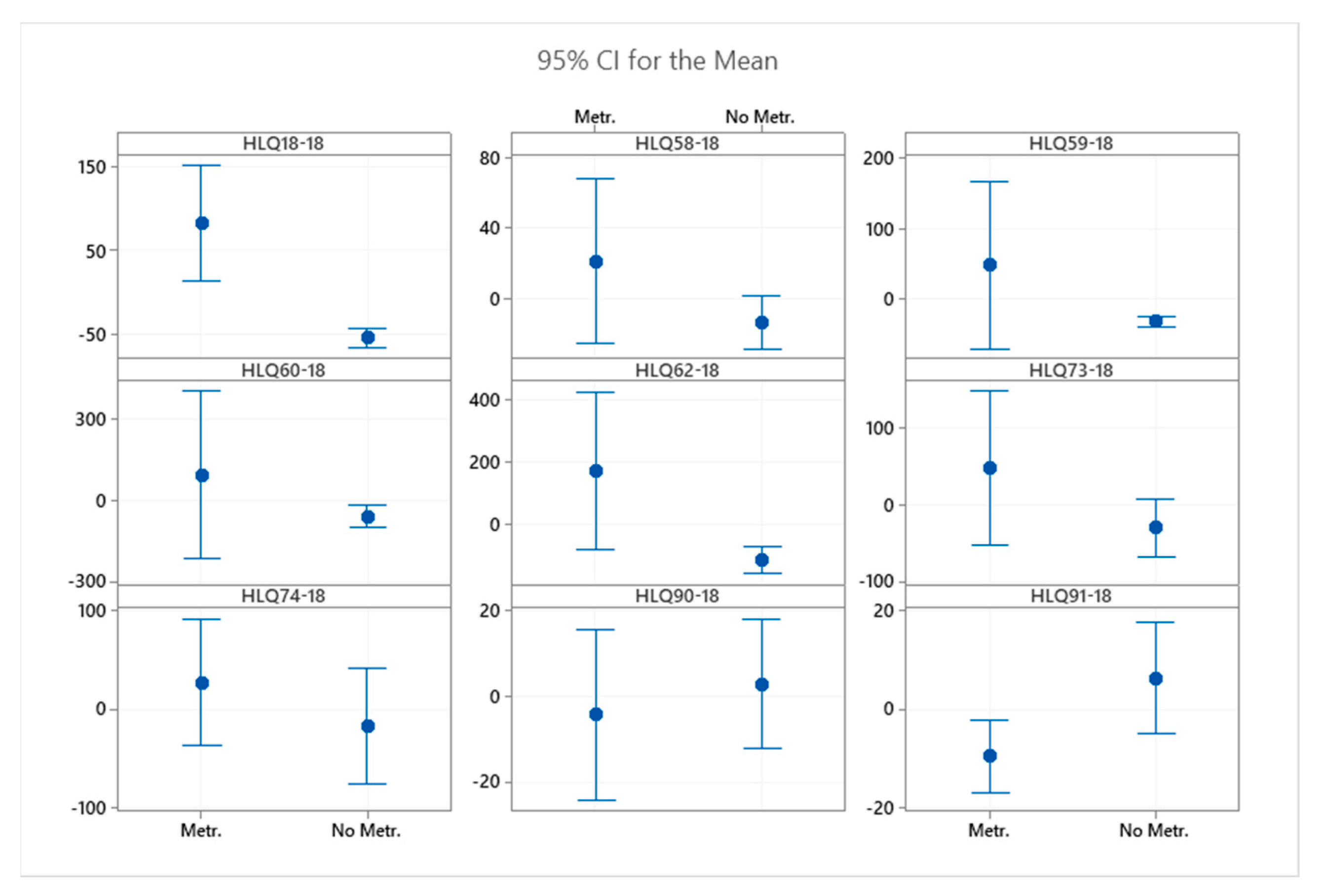

3.2. Methods for Analysis of the Dynamism, Specialization, and Clustering of Ecosystems during the Financial Crisis

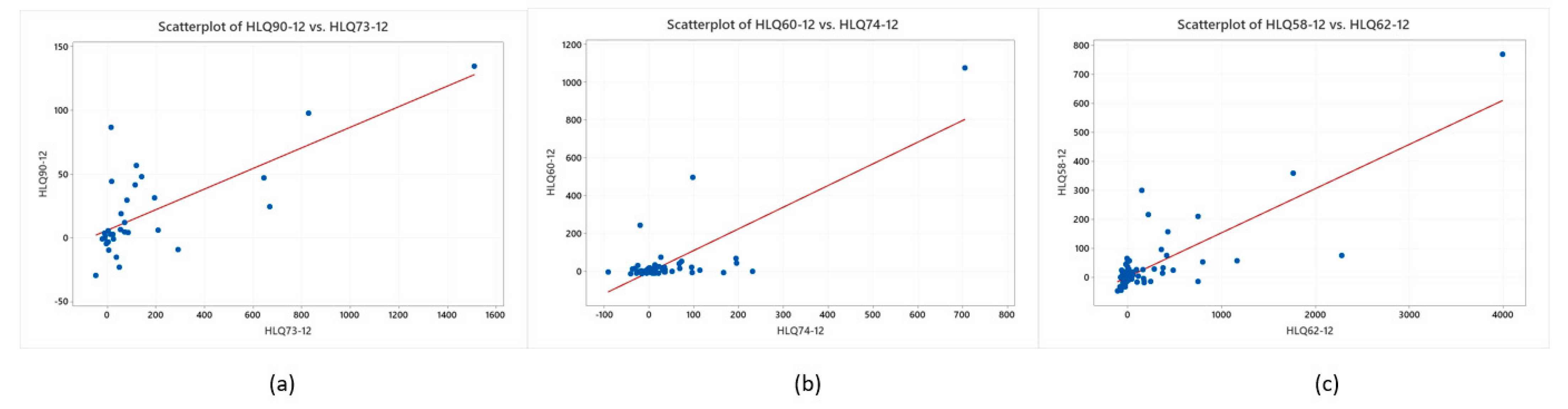

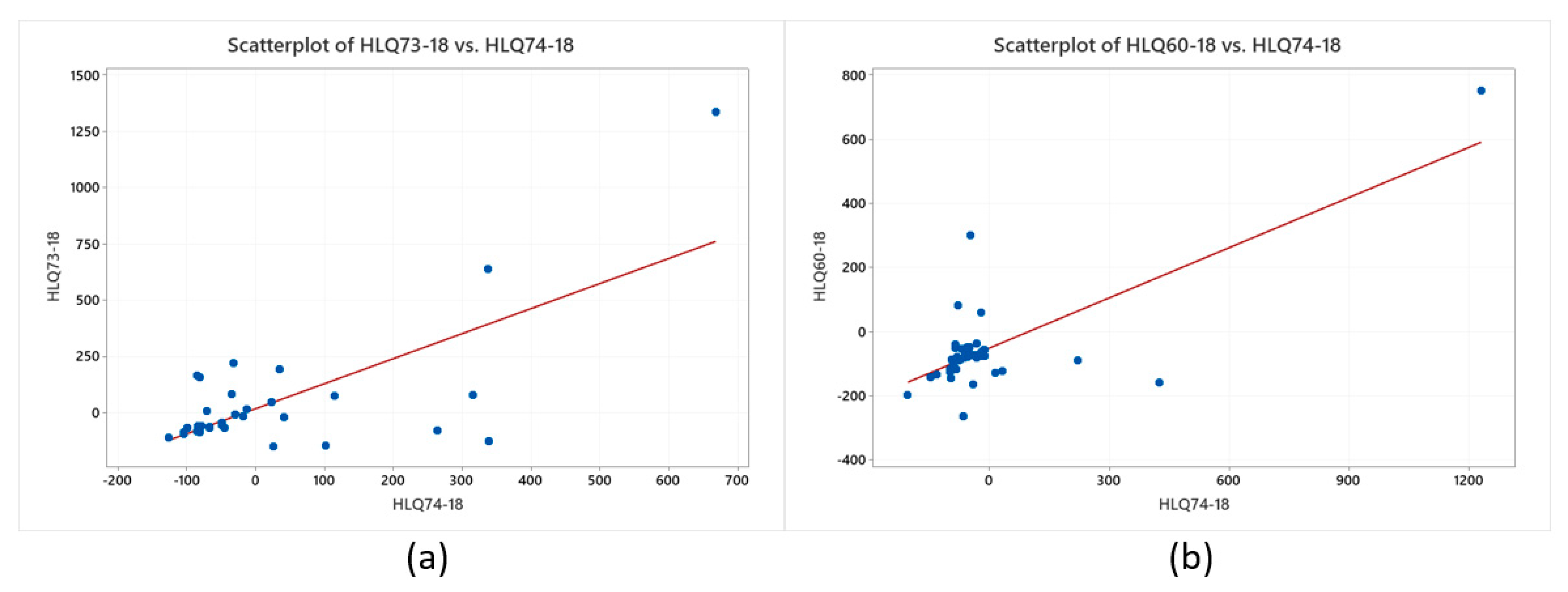

To establish the dynamism of the different ecosystems, data on average employment, standard deviation, and coefficients of variation by city and sector for both 2012 and 2018 were compared. With regard to sectoral specialization, we employed the horizontal localization quotient (HLQ), a measure similar to the conventional quotient but which takes into account the size of the activity in the town or city observed [39]. (This defines the number of firms or jobs in an activity that exceeds the expected number, this being the existing number when the activity in the city has the same importance as a reference space producing a LQ equal to 1. It is calculated for jobs by first obtaining the LQ expressed as LQ = (Eij/Ej)/(Ei/E), with LQ being the location quotient of activity i in the city j; Eij are the jobs from activity i in city j; Ej are all the jobs of j; Ei are the jobs from activity i in the entire study area; and E is the total number of jobs in the study area. Then, Eij is replaced by Êij to obtain LQ = (Êij/Ej)/(Ei/E) = 1, with Êij being the number of jobs necessary for LQ = 1, given the other values. Finally, HLQ is obtained by calculating HLQ = Eij − Êij. With the variable for firms, the process is the same [39]). The HLQ denotes the existence of relative specialization when the result is a positive value. In addition, the statistical significance of the differences in specialization found in the selected cities in 2012 and 2018 was evaluated by contrasting means. Finally, the location quotients were correlated to identify statistically significant co-location patterns between the various sectors, which would be an indication of synergies or interrelationships between coinciding sectors of a city, thus conferring on that city the status of a functional cluster or hub. The analysis compared the situation in 2012 with that of 2018. Correlations were obtained for three sets of cities, i.e., the entirety of the sample, metropolitan cities, and non-metropolitan cities, requiring a minimum value of R = 0.7 to consider the correlation as meaningful, and accepting that the location of one sector influences that of the other (and vice versa).

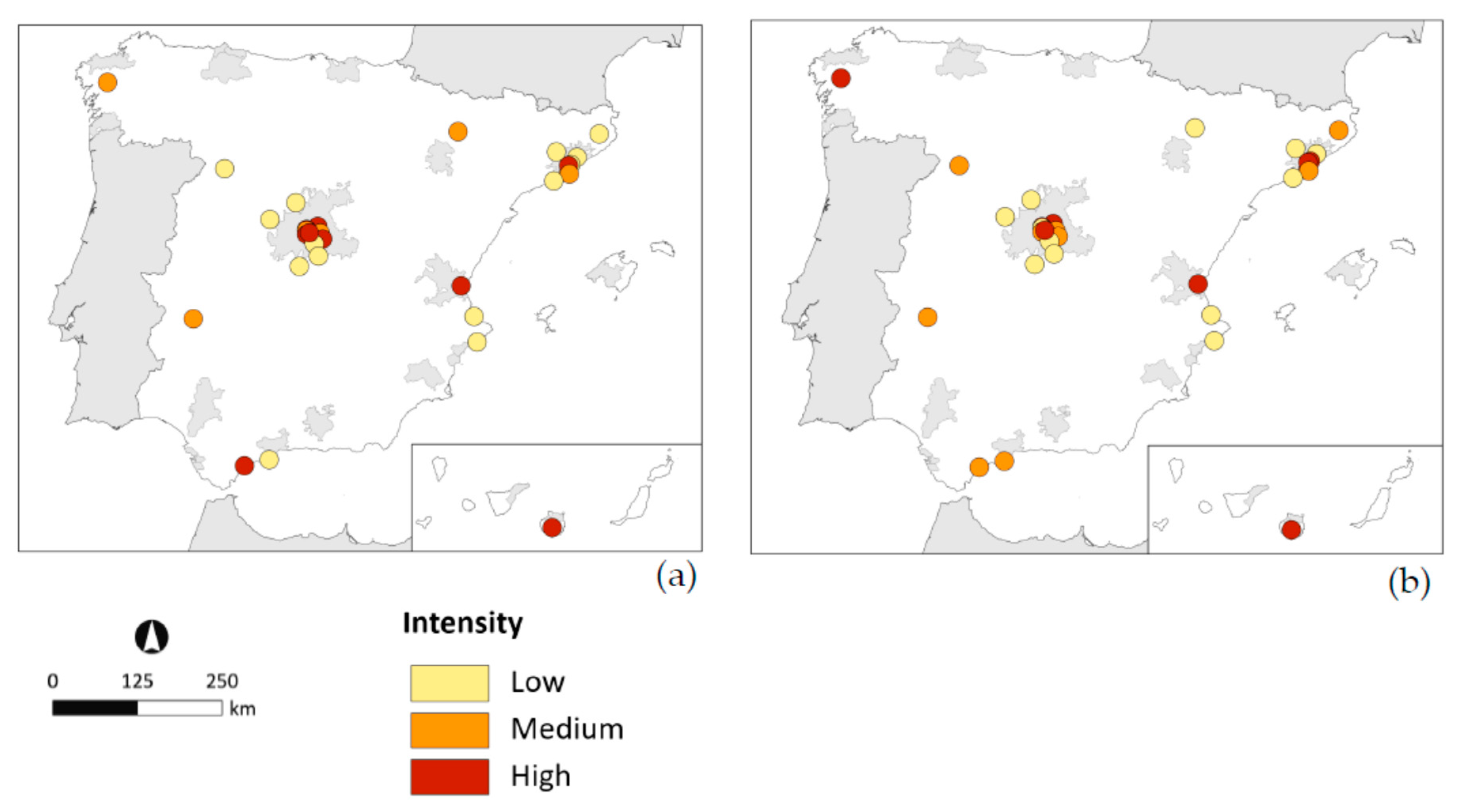

3.3. Indexes to Establish the Exposure of Cultural Ecosystems to the Impact of the Pandemic

The indicators that make up the Cultural and Creative Monitor tool, previously mentioned, provide valuable information on what was already at stake in cultural and creative ecosystems when the COVID-19 pandemic erupted. Here, we followed Montalto et al. [24] and developed, based on our own prior work [21,22], five indexes to evaluate the risks to which ecosystems were exposed according to the intensity of their use in the most affected sectors, as well as to assess the opportunities open to them based on the vitality of their cultural supply and their accessibility to surrounding areas. These indexes are:

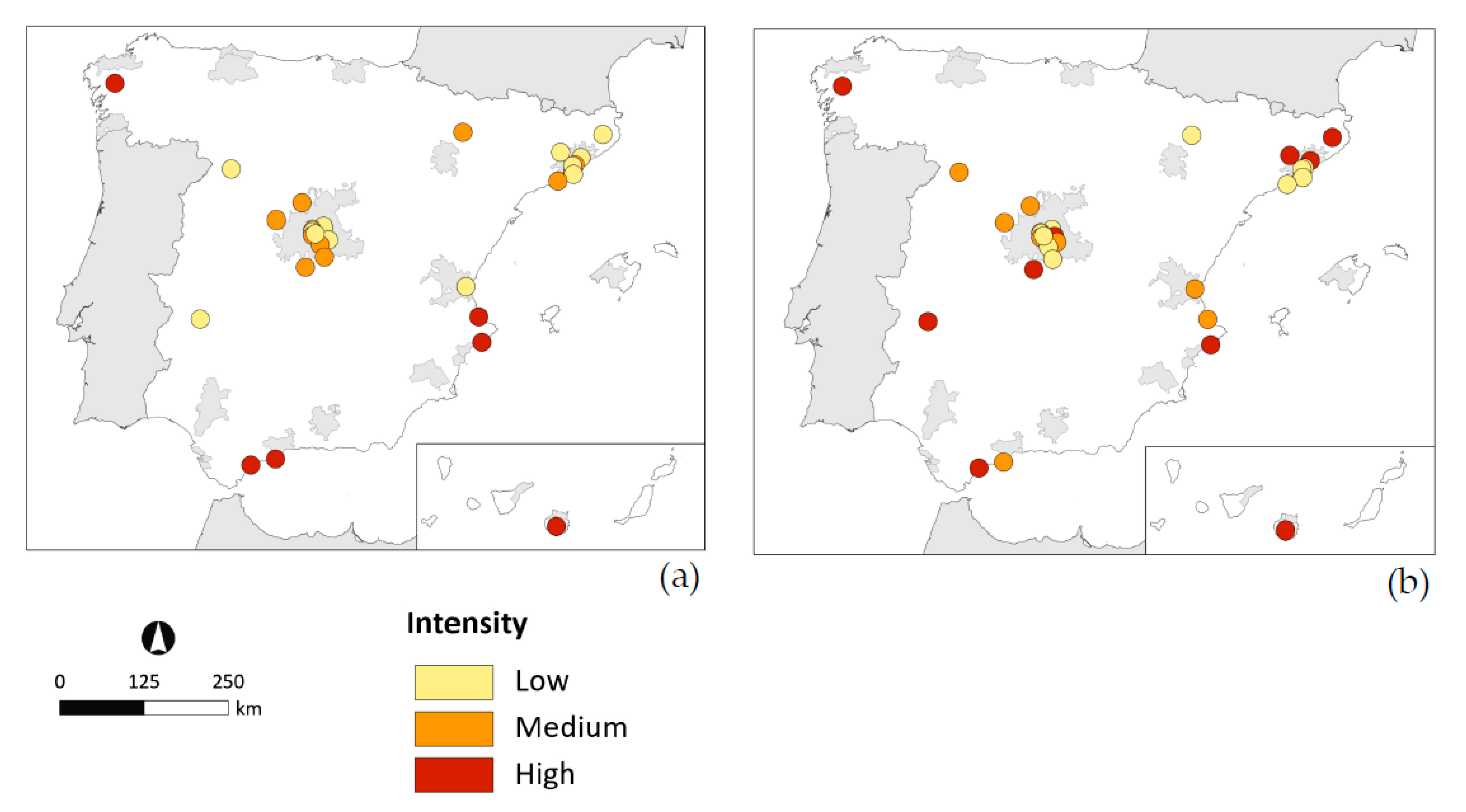

- (a)

- The index of employment intensity in cultural sectors is based on the score achieved by the cities in Indicator 10 of the CCCM,“‘jobs in arts, culture, and entertainment”, obtained from the number of jobs in arts, culture, and entertainment-related activities including in performing arts, museums, and libraries (NACE Rev. 2, codes 90 and 91), divided by the total population in 2019, then multiplied by 1000. The source of statistics used is that of ‘Affiliates with employment registration’ from the Social Security Treasury (‘Afiliados en alta laboral’, Tesorería de la Seguridad Social). Next, the intensity of employment is calculated and categorized by relating the resulting scores to the mean and standard deviation of all cities, and by categorizing the resulting intensity as follows [24]: ”very high intensity” if the score of the city is above the value of the standard deviation, ”high intensity” if the score is below the value of the standard deviation but above the value of the mean, ”medium intensity” if the score is below the mean value but above the value of the standard deviation (multiplied by −1), and ”low intensity” if the score is below the value of the standard deviation (multiplied by −1).

- (b)

- For the index of overnight tourist stays, we begin with the score achieved by the cities in Indicator 6 of the CCCM, ”fourist overnight stays”, obtained from the total annual number of nights that tourists or guests spent in establishments of tourist accommodation (hotels or similar) in the city in 2018, divided by the total population in 2019. The statistical source used here is the National Statistical Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, or INE). Next, the intensity of tourist activity is calculated and categorized, proceeding as indicated in the case of the intensity of cultural employment.

- (c)

- The index of employment intensity in the media and in sectors related to communication is based on the score of the cities in CCCM Indicator 11, ”jobs in media and communication”, obtained from the number of jobs in media and communication-related activities such as book and music publishing, film and TV production (NACE Rev. 2, 58–60 and 62–63), divided by the total 2019 population, and then multiplied by 1000. The source and the categorization criteria are those indicated for the cultural employment intensity index.

- (d)

- The index of employment intensity in other creative sectors is based on the score of the cities in Indicator 12 of the CCCM, obtained from the “number of jobs in professional, scientific and technical, administrative and support service activities such as architecture, advertising, design, and photographic activities” (NACE Rev. 2, 69–74), divided by the total 2019 population, and then multiplied by 1000. The source and the categorization criteria are those already indicated for the two preceding employment intensity indicators.

- (e)

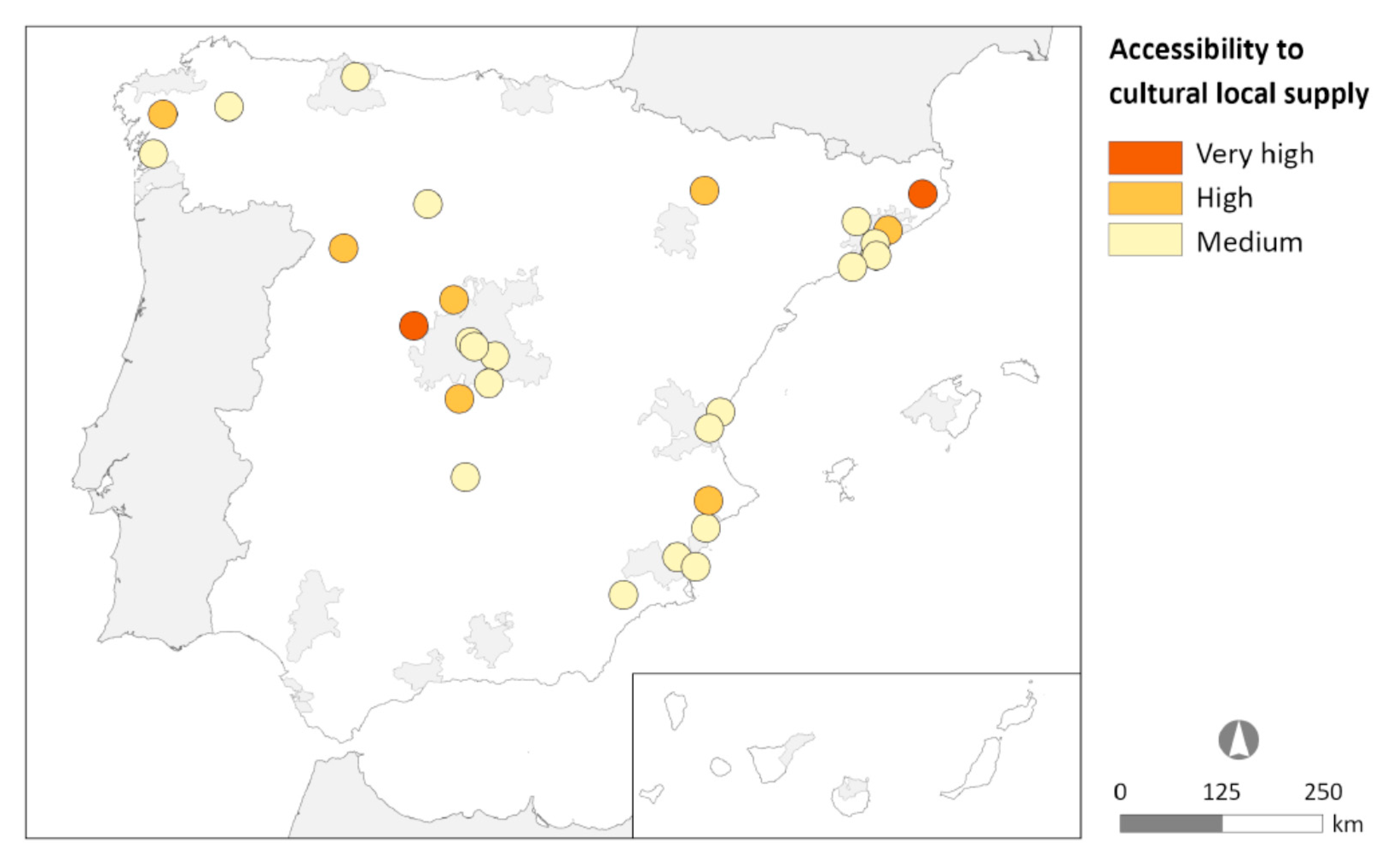

- The index of accessibility to the local cultural supply synthesizes the score achieved by the cities in the cultural venues and facilities dimension (itself an integration of diverse expressive indicators of the cultural supply) and in Indicator 27 of the CCCM, “potential road accessibility”, which assesses the population accessible by road within 90 min travel time, as a share of the population within a 120 km radius. Each of the components of the new index has been categorized as explained for the intensity indexes (that is, by relating the individual scores of the cities with the mean and the standard deviation). In this final typology, the following three categories have been established: “very high” for cities included in the high category of cultural venues and facilities and for potential road accessibility; “high” for cities included in the high category in cultural venues and facilities, and medium in terms of potential road accessibility; and “medium high” for medium-category cities according to cultural venues and facilities with high and medium status according to road accessibility.

5. Conclusions

This work has sought to forecast the short- and medium-term impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the cultural and creative ecosystems of 81 Spanish cities with between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants, thus, complementing a wide series of studies that have addressed this question from different points of view. The aspects chosen for analysis were three relevant attributes of urban cultural and creative ecosystems. i.e., their dynamism, their specialization, and their propensity to form clusters; aspects recognized in the bibliography for their association with the positive development of said ecosystems. We set out the following three queries: how the pandemic might affect the behavior of ecosystems, in what way their specializations might be altered, and what expectations the pandemic would likely raise in relation to their processes of functional clustering. The applied methodology consisted of comparing the three noted attributes in 2012 and 2018, the peak and terminal years of the financial crisis. The changes observed have been interpreted in light of arguments provided in the literature, finally assessing the probability of their recurrence (or non-recurrence) during the current pandemic, according to the peculiarities of this present crisis and the potential exposure of the cities to its effects.

The different analyses undertake a repetition during the pandemic of certain effects observed during the previous crisis that can be predicted. We believe that the factors that determined the asymmetric behavior of sectors and cities during the prior crisis continue to be valid, as do those that allowed the specialization of cultural ecosystems (and contrasts between metropolitan and non-metropolitan ecosystems) to be maintained, as explained above in relation to the effects of borrowed size and centrality. In addition, processes that during the financial crisis led to the disappearance of co-locations which had configured a number of cities as ”hotspots” for the most digitized creative sectors likewise remain in force and have even accelerated.

Our forecasts have also taken into account factors inherent to the current crisis, including the degree of physical presence required by some cultural activities and the weight of the most vulnerable sectors (whether due to a city’s characteristics or its dependence on tourism and mobility, among other factors). On the one hand, the indicators developed to establish the intensity of exposure to risk have shown, in particular, the vulnerability of non-metropolitan cities, although some of these cities also appear to be positioned to take advantage of their good cultural supply and accessibility, in compensation for a loss of extra-regional cultural consumers. On the other hand, the position of metropolitan cities seems more secure, for two reasons, i.e., their weaker connection to those cultural sectors most affected by the pandemic, and a greater presence of sectors that are least vulnerable (due to high and accelerated digitization).

We have also referred to the existence in these ecosystems of certain structural features that become more visible during times of crisis, such as the precariousness of many cultural and creative firms, forcing cultural workers to support themselves under difficult conditions, with low income and an uncertain future [41]. As Comunian and England [18] say, we can ask ourselves “if COVID-19 represents a moment of crisis for the sector or has simply exposed the unsustainable price of cultural and creative work” [18] (p. 112). It also seems clear that the effects of the pandemic on the ecosystems of these cities will be directly related to the survival capacity of their businesses. At this point we have evaluated the potential of ecosystems to provide local cultural services according to accessibility to their cultural supply and we have found some promising cases.

The data and analysis provided, in this work on the cultural and creative ecosystems of medium-sized cities, may serve to support specific policies proposed elsewhere, which can only be briefly mentioned here. For example, the design of new business models and new activity formats to guarantee both security and financial viability; the strengthening of links between public and private components of the cultural ecosystems of the cities; the exploration of opportunities for cooperation with other local sectors (education, tourism, health) to maximize the contribution of culture to social well-being; and others [2,10,18,24].

In the Spanish case, non-metropolitan cities appear to be more vulnerable to the crisis for their strong connection to creative sectors most affected by the pandemic, whereas metropolitan cities seem more secure, thanks to the higher presence of less vulnerable sectors. In the former, all these general policies proposed in the international literature collide with the reality of the sector, clearly specialized in cultural consumption and tourism rather than in cultural production [13]. Therefore, the priority should be to advance policies aimed at protecting employment and cultural organizations as a first measure in the development of new agendas toward more creative social economies.

Author Contributions

All the authors have contributed in similar proportion to the development of this work. The sections have been developed jointly and coordinated among all authors. The supervisory task corresponded to the first signatory author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research forms part the competitive project “Culture and territory in Spain: Processes and impacts in small and medium-sized cities” (references CSO2017-83603-C2-1-R and CSO2017-83603-C2-2-R), financed by the State Research Program “Development and Innovation Oriented to the Challenges of Society” of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, within the framework of the State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation, 2013-2016. In addition, the work has had a grant for the publication of the Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Ciencias Ambientales, University of Zaragoza, in its 2020 call.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding organization has no role in the design of the study; in the collection analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Magnant, C. EU Cultural and Creative Sectors Policies in Crisis Times. In Presentation of JRC Report ‘European Cultural and Creative Cities in COVID-19 times, European Commission, 7 July 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/1._catherine_magnant_-_jrc_-_ccis-covid_event-2-ppt-2.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Travkina, E.; Sacco, P.L.; Morari, B. Culture Shock: COVID-19 and the Cultural and Creative Sectors, In OECD Responses to Coronavirus (COVID–19), 7 September 2020. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Rizzo, I.; Throsby, D. Cultural heritage: Economic analysis and public policy. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, 1st ed.; Ginsburg, V., Throsby, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 983–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does culture affect economic outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G. Understanding culture-led local development: A critique of alternative theoretical explanations. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Hassink, R. Exploring the clustering of creative industries. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F.; Innocenti, N.; Boix, R. Exploring the intellectual structure of creative economy research and local economic development: A co-citation analysis. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1693–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoever, J. On comprehensive wealth, institutional quality and sustainable development-quantifying the effect of institutional quality on sustainability. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, V.; Tacao Moura, C.J.; Alberti, V.; Panella, F.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor; European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Ispra, Italy, 2019; p. 114, JRC117336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Heinonen, J.; Burlina, C.; Comunian, R.; Conor, B.; Crociatta, A.; Dent, T.; Guardans, I.; Hytti, U.; Hytönen, K.; et al. Managing Creative Economies as Cultural Eco-Systems. Available online: https://disce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/DISCE-Policy-Brief-1.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2TksBnPjtTlKciwcurr2X7pyGK4o4Fc3gKVv8A9mYyBNyNyjHfhoqbbdw (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Gross, J.; Wilson, N. Cultural Democracy: An Ecological and Capabilities Approach. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2018, 26, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Raines, N.; Pender, J. Comprehensive wealth accounting: Bridging place-based and people-based measures of wealth. In Rural Wealth Creation, 1st ed.; Pender, J., Johnson, T., Weber, B., Fannin, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 30–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barrado-Timón, D.; Palacios, A.; Hidalgo-Giralt, C. Medium and Small Cities, Culture and the Economy of Culture. A Review of the Approach to the Case of Spain in Light of International Scientific Scholarship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona, A.; Sáez, L.; Sánchez-Valverde, B. Patterns and drivers of cultural economy in Spain’s extra-metropolitan small towns. Investig. Reg. J. Reg. Res. 2017, 38, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona, A.; Sáez, L.; Sánchez-Valverde, B. Location conditions for the clustering of creative activities in extra-metropolitan areas: Analysis and evidence from Spain. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrado, D.; Escalona, A.; Escolano, S.; Sánchez, B. Creative clusters outside and within metropolitan areas: A comparative analysis. In Proceedings of the Fifth Global Conference on Economic Geography, Session 97: The Economic Geography of Creative Industries IV, Köln, Germany, 24–28 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barrado, D.; Escalona, A.; Escolano, S.; Sánchez, B. Los clusters de industrias culturales en pequeñas y medianas ciudades intra y extrametropolitanas. In Un análisis comparado, Proceedings of the International Conference on Regional Science, Valencia, Spain, 4–6 July 2018; Hacia un modelo económico más social y sostenible; XLIV Reunión de Estudios Regionales: Valencia, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330752856_Los_clusters_de_industrias_culturales_en_pequenas_y_medianas_ciudades_intra_y_extrametropolitanas_Un_analisis_comparadodoc (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Comunian, R.; England, L. Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cult. Trends 2020, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A. A world turned upside down: The cultural economy. In Proceedings of the Cities and the New Austerity, Smart, Creative, Sustainable, Inclusive: Territorial Development Strategies in the Age of Austerity, Regional Studies Association Winter Conference, London, UK, 23 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Montalto, V.; Moura, C.J.T.; Langedijk, S.; Saisana, M. Culture counts: An empirical approach to measure the cultural and creative vitality of European cities. Cities 2019, 89, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona-Orcao, A.I.; Escolano-Utrilla, S.; Sánchez-Valverde, B.; Sáez-Pérez, L.; Conejos-Sevillano, A. Creative and cultural ecologies in small cities. Nature, interpretation and evaluation. In Creative Industries Research Frontiers: Seminar Series Seminar 1. Creative and Cultural Ecologies: Mapping and Understanding; King’s College: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona-Orcao, A.I.; Escolano-Utrilla, S.; Sánchez-Valverde, B.; Sáez-Pérez, L.; Conejos-Sevillano, A. Dinamismo creativo y cultural en las pequeñas ciudades. In Proceedings of the Las Actividades Culturales en las Pequeñas y Medianas ciudades, Huesca, Spain, 30–31 January 2020. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Betzler, D.; Loots, E.; Prokůpek, M.; Marques, L.; Grafenauer, P. COVID-19 and the arts and cultural sectors: Investigating countries’ contextual factors and early policy measures. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, V.; Sacco, P.L.; Alberti, V.; Panella, F.; Saisana, M. European Cultural and Creative Cities in COVID-19 Times. Jobs at Risk and the Policy Response; Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Montalto, V.; Tacao Moura, C.J.; Langedijk, S.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor; European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Ispra, Italy, 2017; p. 114, JRC107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.R.; Kabwasa-Green, F.; Herranz, J. Cultural Vitality in Communities: Interpretation and Indicators, 1st ed.; Culture, Creativity and Communities Program, The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Gritsai, O. The creative knowledge city in Europe: Structural conditions and urban policy strategies for competitive cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 20, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Propris, L.; Chapain, C.; Cooke, P.; Macneil, S.; Mateos, M. The Geography of Creativity, 1st ed.; Nesta: London, UK, 2009; p. 80. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30684522.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Alonso, W. Urban zero population growth. Daedalus 1973, 102, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Meijers, E.J.; Burger, M.J. Stretching the concept of ‘borrowed size’. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona-Orcao, A.I.; Escolano-Utrilla, S.; Sáez-Pérez, L.A.; Sánchez-Valverde García, B. The location of creative clusters in non-metropolitan areas: A methodological proposition. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Boix, R.; Capone, F. Do Creative Industries Cluster? Mapping Creative Local Production Systems in Italy and Spain. Ind. Innov. 2008, 15, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Propris, L. How are creative industries weathering the crisis? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2012, 6, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F.; Boix, R. Reasons for Clustering of Creative Industries in Italy and Spain. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1243–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NESTA. Digital Culture, 1st ed.; NESTA, Arts Council England: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Digital-Culture-2019.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Florida, R.; Seaman, M. Measuring COVID-19’s Devastating Impact on America’s Creative Economy, 1st ed.; Brookings, Metropolitan Policy Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 30. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20200810_Brookingsmetro_Covid19-and-creative-economy_Final.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Dubini, P. L’effetto Domino Del Covid-19 Sull’economia Delle Filiere Cultural. Available online: https://agcult.it/a/16656/2020-03-31/sviluppo-sostenibile-l-effetto-domino-del-covid-19-sull-economia-delle-filiere-culturali (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Pratt, A.C. Beyond resilience: Learning from the cultural economy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingleton, B.; Camargo Igliori, D.; Moore, B. Employment growth of small high-technology firms and the role of horizontal clustering: Evidence from computing services and R&D in Great Britain, 1991–2000. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 773–799. [Google Scholar]

- KEA & PPMI. Research for CULT Committee—Culture and Creative Sectors in the European Union-Key Future Developments, Challenges and Opportunities, 1st ed.; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Between culture, policy and industry: Modalities of intermediation in the creative economy. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).