Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Settings

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Personal Diet and Motivations

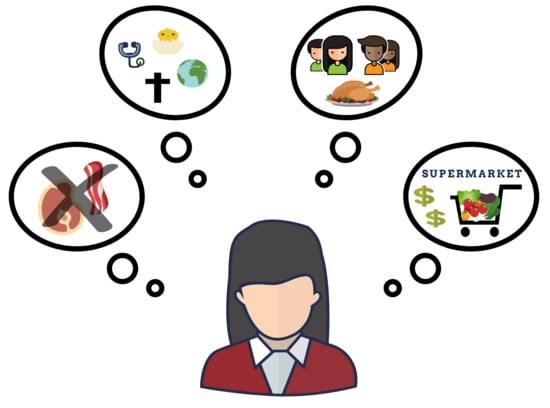

3.3. Socio-Cultural Environment

3.4. Availability of Plant-Based Foods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable diets and biodiversity: Directions and solutions for policy, research and action. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets, United against Hunger, Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; De Clerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Heller, M.C.; Roberto, C.A. Position of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior: The Importance of Including Environmental Sustainability in Dietary Guidance. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 3–15.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagtow, A.; Robien, K.; Bergquist, E.; Bruening, M.; Dierks, L.; Hartman, B.E.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Steinitz, T.; Tahsin, B.; Underwood, T.; et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Standards of Professional Performance for Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (Competent, Proficient, and Expert) in Sustainable, Resilient, and Healthy Food and Water Systems. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 475–488.e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvard University. What Is a Plant-Based Diet and Why Should You Try It? 2018. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-a-plant-based-diet-and-why-should-you-try-it-2018092614760 (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Baroni, L.; Cenci, L.; Tettamanti, M.; Berati, M. Evaluating the environmental impact of various dietary patterns combined with different food production systems. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soret, S.; Mejia, A.; Batech, M.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Harwatt, H.; Sabate, J. Climate change mitigation and health effects of varied dietary patterns in real-life settings throughout North America. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 490S–495S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J.; Harwatt, H.; Soret, S. Health outcomes and greenhouse gas emissions from varied dietary patterns– is there a relationship? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 67, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sabate, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Global sustainability (health, environment and monetary costs) of three dietary patterns: Results from a Spanish cohort (the SUN project). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e021541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Share of People Who Follow a Vegetarian Diet Worldwide as of 2016, by Region. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/597408/vegetarian-diet-followers-worldwide-by-region/ (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Janssen, M.; Busch, C.; Rodiger, M.; Hamm, U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 2016, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H. A comparison of attitudes toward meat and animals among strict and semi-vegetarians. Appetite 2014, 72, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012, 58, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.; Ward, K. Health, ethics and environment: A qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite 2008, 50, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M.; Sobal, J. Model of the Process of Adopting Vegetarian Diets: Health Vegetarians and Ethical Vegetarians. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.I.; Chapman, G.E. Perceptions and practices of self-defined current vegetarian, former vegetarian, and nonvegetarian women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrin, T.; Papadopoulos, A. Understanding the attitudes and perceptions of vegetarian and plant-based diets to shape future health promotion programs. Appetite 2017, 109, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, L.K.; Farrow, C.; Thomas, J.M. Do perceived norms of social media users’ eating habits and preferences predict our own food consumption and BMI? Appetite 2020, 149, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Society for Nutrition and Behaviour. Vegetarian Trends. Available online: https://www.sneb.org/blog/2018/04/03/general/vegetarian-trends/ (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J.J.R.E.C. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterlander, W.E.; Jiang, Y.; Nghiem, N.; Eyles, H.; Wilson, N.; Cleghorn, C.; Genç, M.; Swinburn, B.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Blakely, T. The effect of food price changes on consumer purchases: A randomised experiment. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e394–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Rowan, M.; Gadhoke, P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. 2017. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/lomalindacitycalifornia (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Danmarks Statistik. Folketal (Summariske tal fra Folketællinger) efter Hovedlandsdele og tid. 2018. Available online: http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/SelectVarVal/saveselections.asp (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Beuttner, D. Blue Zones: The Science of Living Longer; National Geographic: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, G.E. Diet, Life Expectancy, and Chronic Disease: Studies of Seventh-Day Adventists and Other Vegetarians; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, T. Which Foods Are on the 7th Day Adventist Diet? Available online: https://www.livestrong.com/article/441583-what-foods-are-on-the-7th-day-adventist-diet/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- European Union. Copenhagen European Green Capital 2014. 2013. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Copenhagen-Post-Assessment-Report-2014-EN.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Fountain, H.; Nagourney, A. California, at Forefront of Climate Fight, Won’t Back Down to Trump. New York Times. 26 December 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/26/us/california-climate-change-jerry-brown-donald-trump.html (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- NBC Channel 4 Los Angeles. Los Angeles City Council Embraces “Meatless Mondays”. 2012. Available online: https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/Los-Angeles-City-Council-Embraces-Meatless-Mondays-Vegetarian-178244541.html (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Landmark California Legislation Encourages Climate-Friendly, Plant-Based School Lunch Options. 2019. Available online: https://www.pcrm.org/news/news-releases/landmark-california-legislation-encourages-climate-friendly-plant-based-school (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Haverstock, K.; Forgays, D.K. To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite 2012, 58, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuter, R. Finding Companionship on the Road Less Travelled: A Netnography of the Whole Food Plant-Based Aussies Facebook Group. 2018. Available online: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1517/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf;jsessionid=3426EEFACB3E2F9A2CCE6328DD98D183?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 October 2018).

| LOMA LINDA | COPENHAGEN | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | 43 | 186 |

| 1. Gender | ||

| Women | 76.7 | 87.1 |

| Men | 23.3 | 11.8 |

| Preferred not to disclose | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| 2. Age | ||

| 19 years or younger | 0.0 | 9.1 |

| 20–29 years | 53.5 | 54.8 |

| 30–39 years | 11.6 | 17.7 |

| 40–49 years | 11.6 | 13.4 |

| 50–59 years | 16.3 | 3.2 |

| 60–69 years | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| 70 years or older | 4.7 | 0.5 |

| 3. Religion | ||

| Christian | 58.1 | 13.4 |

| Seventh-Day Adventist | 55.8 | 0.0 |

| Other protestant | 2.3 | 13.4 |

| No religion | 9.3 | 70.4 |

| Others | 32.6 | 16.2 |

| 4. Level of Education | ||

| High school graduate | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| College degree | 9.3 | 25.3 |

| Undergraduate/Bachelor’s degree | 39.5 | 30.6 |

| Graduate/Master’s degree | 34.9 | 19.9 |

| Doctoral Degree | 11.6 | 2.7 |

| Professional degree | 4.7 | 10.8 |

| Other | 0.0 | 5.9 |

| LOMA LINDA | COPENHAGEN | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | 43 | 186 |

| 1. Which diet do you follow on a regular basis? | ||

| Flexitarian (eats meat, poultry, or fish occasionally) | 39.5 | 21.0 |

| Pescatarian (eats fish and dairy and/or eggs, but not meat) | 16.3 | 6.5 |

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarian (eats dairy or eggs or both, but not meat nor fish) | 25.6 | 24.7 |

| Vegan (eats only plant foods) | 18.6 | 47.8 |

| 2. How long have you followed this diet? | ||

| Less than 1 year | 7.0 | 21.0 |

| 1–5 years | 23.3 | 51.1 |

| 5–10 years | 9.3 | 15.6 |

| 10–15 years | 16.3 | 4.8 |

| 15–20 years | 9.3 | 1.1 |

| 20 years or more | 34.9 | 6.5 |

| 3. Which of the following areas motivated you to start your diet? | ||

| Health | 53.5 | 22.6 |

| Weight loss | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| Environment/Climate change | 0.0 | 22.0 |

| Animal welfare | 7.0 | 39.8 |

| Social norm (if friends and family eat this way) | 16.3 | 1.1 |

| Religious/Spiritual belief | 11.6 | 0.5 |

| Taste | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Saving money | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Political reasons | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Convenience | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Diet trend | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Other | 11.6 | 5.4 |

| 4. Which of the following areas motivates you to continue this diet? | ||

| Health | 69.8 | 22.0 |

| Weight loss | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Environment/Climate change | 2.3 | 28.5 |

| Animal welfare | 4.7 | 40.9 |

| Social norm (if friends and family eat this way) | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| Religious/Spiritual belief | 7.0 | 0.0 |

| Taste | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| Saving money | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Political reasons | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Habit | 7.0 | 1.6 |

| Convenience | 4.7 | 0.0 |

| Diet trend | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| 5. Would you eat more plant-based than you do now 1, if | ||

| It was cheaper. | 11.4 | 13.4 |

| It tasted better. | 5.7 | 5.2 |

| You could get the plant-based alternative for those food items/dishes you love (e.g., burger, meatballs, chicken tikka masala, cheese, yogurt, butter, etc.). | 8.6 | 1.0 |

| It was more convenient/easier to get plant-based food. | 11.4 | 10.3 |

| It was less time consuming. | 8.6 | 9.3 |

| There would be a greater selection of plant-based items in your supermarkets. | 2.9 | 7.2 |

| More restaurants and cafes offered plant-based meals. | 17.1 | 7.2 |

| More of my friends and family followed the same diet. | 8.6 | 15.5 |

| The person cooking in my home, would cook plant-based meals. | 2.9 | 5.2 |

| None, I am already eating a satisfactory diet. | 11.4 | 23.7 |

| Other | 11.4 | 2.0 |

| LOMA LINDA | COPENHAGEN | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | 43 | 186 |

| 1. Do you follow the same diet as the majority of your family (parents, partner, children)? | ||

| Yes | 48.8 | 21.0 |

| No | 51.2 | 79.0 |

| 2. If no, which diet do the majority of your family follow? | ||

| Omnivore (eats meat and plant food) | 59.1 | 76.2 |

| Flexitarian (eats meat, poultry, or fish occasionally) | 4.5 | 21.1 |

| Pescatarian (eats fish and dairy and/or eggs, but not meat) | 9.1 | 0.0 |

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarian (eats dairy or eggs or both, but not meat nor fish) | 18.2 | 1.4 |

| Vegan (eats only plant foods) | 4.5 | 0.0 |

| Other | 4.6 | 1.3 |

| 3. Do you follow the same diet as the majority of your friends? | ||

| Yes | 27.9 | 14.5 |

| No | 72.1 | 85.5 |

| 4. If no, which diet do the majority of your friends follow? | ||

| Omnivore (eats meat and plant food) | 71.0 | 79.2 |

| Flexitarian (eats meat, poultry, or fish occasionally) | 12.9 | 17.6 |

| Pescatarian (eats fish and dairy and/or eggs, but not meat) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarian (eats dairy or eggs or both, but not meat nor fish) | 9.7 | 1.3 |

| Vegan (eats only plant foods) | 3.2 | 0.0 |

| Other | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| 5. Do you ever compromise your diet because of social pressure? | ||

| Yes, very often. | 2.3 | 13.4 |

| Sometimes. | 41.9 | 27.4 |

| No, rarely. | 55.8 | 59.1 |

| 6. Is eating a more plant-based diet associated with the religion/spiritual beliefs in your city? | ||

| Yes. | 65.1 | 0.0 |

| No. | 27.9 | 86.6 |

| I do not know. | 7.0 | 13.4 |

| 7. According to you, which of the following statements do you think suits best with how lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet is perceived in your city? | ||

| A lifestyle which promotes health. | 67.4 | 8.1 |

| A lifestyle for women. | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| A lifestyle for weight loss. | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| A lifestyle for very health conscious individuals. | 2.3 | 11.3 |

| A lifestyle for lower income families. | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| A lifestyle for higher income families. | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| A lifestyle for certain religious/spiritual beliefs. | 23.3 | 0.5 |

| A lifestyle for individuals who have strong beliefs in animal rights. | 2.3 | 27.4 |

| A lifestyle for addressing and reducing climate change. | 0.0 | 31.2 |

| I do not know. | 2.4 | 16.7 |

| 8. According to you, which of the following statements do you think suits best with how vegan diet is perceived in your city? | ||

| A lifestyle which promotes health. | 25.6 | 2.2 |

| A lifestyle for women. | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| A lifestyle for weight loss. | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| A lifestyle for very health conscious individuals. | 30.2 | 8.1 |

| A lifestyle for lower income families. | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| A lifestyle for higher income families. | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| A lifestyle for certain religious/spiritual beliefs. | 16.3 | 1.6 |

| A lifestyle for individuals who have strong beliefs in animal rights. | 18.6 | 53.2 |

| A lifestyle for addressing and reducing climate change. | 0.0 | 15.6 |

| I do not know. | 7.0 | 16.0 |

| LOMA LINDA | COPENHAGEN | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | 43 | 186 |

| 1. Do you find it easy to shop basic food alternatives suitable for lacto-ovo-vegetarians and/or vegans in your area (such as legumes, tofu, tempeh, vegetable milk, etc.)? | ||

| Yes, it is no problem to find basic plant-based items in the supermarkets here. | 76.7 | 46.8 |

| Most of the time, yes, although I can’t always get what I need from one store. | 23.3 | 48.9 |

| No, I find it difficult to find basic plant-based items in supermarkets here. | 0.0 | 4.3 |

| 2. Do you find it easy to shop ready-to-eat items suitable for lacto-ovo-vegetarians and/or vegans in your area? | ||

| Yes, it is no problem to find lacto-ovo-vegetarian meals in the supermarkets here. | 41.9 | 12.4 |

| Yes, it is no problem to find both lacto-ovo-vegetarian and vegan meals in the supermarkets here. | 18.6 | 27.4 |

| Sometimes. | 25.6 | 39.2 |

| No, I find it difficult to find either. | 7.0 | 12.4 |

| I haven’t looked for it. | 6.9 | 8.6 |

| 3. Do you think that foods suitable for lacto-ovo-vegetarians or vegans are too expensive compared to animal-based foods? | ||

| Yes, lacto-ovo-vegetarian and/or vegan options are more expensive than animal-based ones. | 58.1 | 81.2 |

| I think they are about the same. | 20.9 | 11.8 |

| No, lacto-ovo-vegetarian and/or vegan options are cheaper than animal-based ones. | 16.3 | 2.2 |

| I do not know | 4.7 | 4.8 |

| 4. Is there a lack of lacto-ovo-vegetarian or vegan meal options at your work, school or the place you spend the most of your day? | ||

| Yes, both meal options are missing. | 2.3 | 22.0 |

| They have lacto-ovo-vegetarian meals, but not vegan meal options. | 20.9 | 26.3 |

| Sometimes the options are available. | 9.3 | 12.9 |

| No, the options are available, but the dishes are not very good. | 7.0 | 6.5 |

| No, both meal options are available. | 55.8 | 14.5 |

| Not applicable | 4.7 | 17.8 |

| 5. Is there a lack of lacto-ovo-vegetarian or vegan meals when you eat out? | ||

| Yes, both meal options are missing. | 4.7 | 10.8 |

| Most places have lacto-ovo-vegetarian meals, but not vegan meal options. | 58.1 | 60.2 |

| Sometimes the options are available. | 9.3 | 14.5 |

| No, the options are available, but the dishes are not very good. | 9.3 | 4.8 |

| No, both meal options are available. | 16.3 | 7.0 |

| Other | 2.3 | 2.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fresán, U.; Errendal, S.; Craig, W.J. Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219093

Fresán U, Errendal S, Craig WJ. Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):9093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219093

Chicago/Turabian StyleFresán, Ujué, Sofie Errendal, and Winston J. Craig. 2020. "Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 9093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219093

APA StyleFresán, U., Errendal, S., & Craig, W. J. (2020). Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets. Sustainability, 12(21), 9093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219093