Trust in Courier Services and Its Antecedents as a Determinant of Perceived Service Quality and Future Intention to Use Courier Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Trust as a Determinant of Service Quality—A Literature Review

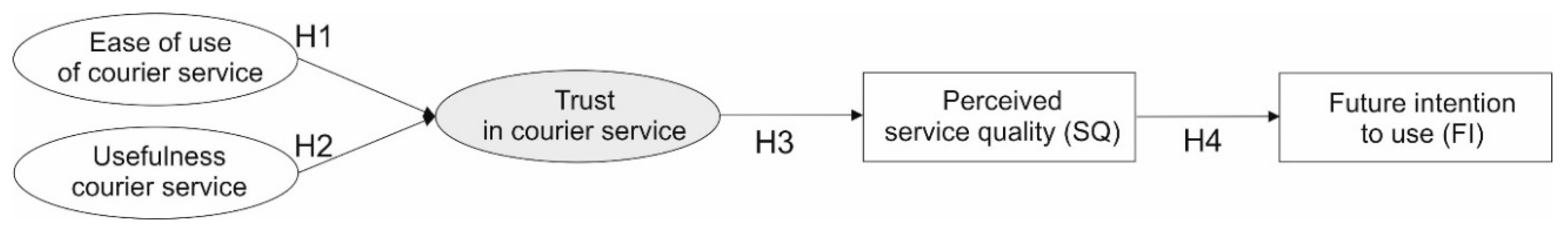

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. Ease of Use, Usefulness and Trust

- Perceived usefulness is the degree to which the user is convinced that using a particular system/technology will improve the results/results of the work/activities;

- Perceived ease of use is the degree to which the user is confident that by using a particular system/technology they will be ‘free’ from physical and mental effort [94].

3.2. Trust and Perceived Service Quality

3.3. Quality and Future Intention

4. Research Methods and Measurement

4.1. Data

4.2. Measures

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Portal, Digital Market Outlook. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/379046/worldwide-retail-e-commerce-sales/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Development of Cross-Border E-Commerce through Parcel Delivery. 2019. Available online: https://www.wik.org/fileadmin/Studien/2019/ET0219218ENN_ParcelsStudy_Final.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Gawryluk, M. Rozwój Rynku Przesyłek Kurierskich, Ekspresowych i Paczkowych (KEP) w Polsce od 2014 r. do 2023 r. Available online: https://media.poczta-polska.pl/pr/465205/poczta-polska-w-2023-roku-rynek-kep-bedzie-mial-wartosc-12-mld-zl (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Gulc, A. Courier service quality in the light of scientific publications. In Economic and Social Development (Book of Proceedings), Proceedings of the 23rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development (ESD), Madrid, Spain, 15–16 September 2017; Cingula, M., Przygoda, M., Detelj, K., Eds.; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2017; pp. 556–565. [Google Scholar]

- Micu, A.; Aivaz, K.; Capatina, A. Implications of logistic service quality on the satisfaction level and retention rate of an e-commerce retailer’s customers. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cyb. 2013, 47, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jarocka, M. The Issue of Logistics Services in the International Scientific Literature. In Proceedings of the 8th Carpathian Logistics Congress on Logistics, Distribution, Transport and Management (CLC), Prague, Czech Republic, 3–5 December 2018; pp. 508–513. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, H.L.; Daud, D. Measuring Customer Satisfaction in the Parcel Service Delivery: A Pilot Study in Malaysia. Bus. Econ. Res. 2011, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, M.; Yang, Z.; Kim, D. Customers’ perceptions of online retailing service quality and their satisfaction. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2004, 21, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-Commerce w Polsce. 2018. Available online: https://eizba.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/raport_GEMIUS_2019-1.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Choi, Y.; Mai, D. The sustainable role of the e-trust in the B2C e-commerce of Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Sustainable Online Shopping Logistics for Customer Satisfaction and Repeat Purchasing Behavior: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, B.; Calabretta, G.; Bocken, N.; Jaskiewicz, T. Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: A process for sustainable value proposition design. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 147, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, M. The modified Kansei Engineering-based application for sustainable service design. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020, 79, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, M.; Santoso, A.; Prayogo, D.N. How Kansei Engineering, Kano and QFD can improve logistics services. Int. J. Technol. 2017, 8, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillat, F.A.; Jaramillo, F.; Mulki, J.P. The validity of the SERVQUAL and SERVPERF scales: A metanalytic view of 17 years of research across five continents. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2007, 18, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Strategic Management and Marketing in the Service Sector; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, U.; Lehtinen, J.R. A Study of Quality Dimensions. Serv. Manag. Inst. 1982, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.C.; Booms, B.H. The marketing aspect of service quality. In Emerging Perspective on Service Marketing; Berry, L., Shostack, G., Upah, G., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983; pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, I.G.; Frances, D.S.; Contri, G.B.; Blasco, M.F. Logistics service quality: A new way to loyalty. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2008, 108, 650–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.G.; Grewal, D.; Levy, M. The Customer Satisfaction/Logistics Interface. J. Bus Log. 1995, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, H.; Roy, S.; Shergill, G.; Pritchard, A. Modelling trust in service relationships: A transnational perspective. J. Serv. Mark 2013, 27, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, M. Wymiary zaufania w procesie świadczenia usług. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego 2012, 95, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Ruan, W.; Park, Y. Effects of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Customer Trust on the Corporate Reputation of Airlines. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Ozer, G. The Analysis of Antecedents of Customer Loyalty in the Turkish Mobile Telecommunications Market. Eur. J. Mark 2005, 39, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulc, A. Courier service quality from the clients’ perspective. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2017, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chow, S.; Holden, R. Toward an understanding of loyalty: The moderating role of trust. J. Manag. Issues 1997, 9, 275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.B.; Eom, S.B. Designing effective cyber store user interface. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2002, 102, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, C.N.; Madu, A.A. Dimensions of e-quality. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2002, 19, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Ying, H.Y. Chang YF The critical factors impact on online customer satisfaction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 3, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Service excellence in electronic channels. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2002, 12, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing a scale to measure the perceived quality of an Internet shopping site (SITEQUAL). Q. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 2, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, C.S. Customer Evaluation of Internet-Based Service Quality and Intention to Re-Use Internet-Based Services; Southern Illinois University: Carbondale, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.K.; Cheung, W.; Tang, M. Building trust online: Interactions among trust building mechanisms. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavareh, F.B.; Md Ariffa, M.S.; Jusoha, A.; Zakuana, N.; Bahari, A.Z.; Ashourian, M. E-Service Quality Dimensions and Their Effects on ECustomer Satisfaction in Internet Banking Services. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Oliveira, T.; Farisa, A. The impact of e-service quality and customer satisfaction on customer behavior in online shopping. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.A.; Zahra, S.; Yaseen, A. Impact of service quality and trust on repurchase intentions—The case of Pakistan airline industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 1136–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aren, S.; Güzelb, M.; Kabadayi, E.; Albkan, L. Factors Affecting Repurchase Intention to Shop at the Same Website. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punuindoong, D.H.F.; Syah, T.Y.R. Affecting Factors over Repurchase Shop Intention at E-Commerce Industry. Sci. Eng. Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gulc, A. Determinants of Courier Service Quality in e-Commerce from Customers’ Perspective. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2020, 24, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.S.Y.; Teik, D.O.L.; Tiffany, F.; Kok, L.F.; Teh, T.Y. Logistic Service Quality among Courier Services in Malaysia. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 38, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J.B. A news scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J. Pers. 1967, 35, 561–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möllering, G. The nature of trust: From Georg Simmel to a theory of expectation, interpretation and suspension. Sociology 2001, 35, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Gavin, M.B. Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoorman, F.D.; Ballinger, G.A. Leadership, trust and client service in veterinary hospitals. In Working Paper; Purdue University: West Lafayett, Indiana, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Kim, H.M.; Kolb, J.A. The Effect of Learning Organization Culture on the Relationship between Interpersonal Trust and Organizational Commitment. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2009, 20, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, D.E. Reflections on trust and trust research: Then and now. J. Trust Res. 2016, 6, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.M.; Jung, C.S. Focusing the mediating role of institutional trust: How does interpersonal trust promote organizational commitment? Soc. Sci. J. 2015, 52, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, A.C.; Berman, S.L. The effects of context on trust in firm-stakeholder relationships: The institutional environment, trust creation, and firm performance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankton, N.K.; McKnight, D.H.; Thatcher, J.B. Incorporating trust-in-technology into Expectation Disconfirmation Theory. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, S.K. An Exploratory Study into The Relevance of Trust in the Context of Information Systems Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, M.G.; Curcuruto, M.; Zavalloni, M. Online Recruitment: The role of trust in technology. Psicol. Soc. 2016, 11, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Le, K.; Deitermann, A.; Montague, E. How different types of users develop trust in technology: A qualitative analysis of the antecedents of active and passive user trust in a shared technology. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Gal, H.C.; Tzafrir, S.S.; Dolan, S.L. Actionable trust in service organizations: A multi-dimensional perspective. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 31, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K.S.; Coulter, R.A. The effects of industry knowledge on the development of trust in service relationships. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2003, 20, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantsperger, R.; Kunz, W.H. Consumer trust in service companies: A multiple mediating analysis. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2010, 20, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, Z.; Sun, S.; Abrokwah, E.; Kofi Penney, E.; Ofori-Boafo, R. Influence of Trust on Customer Engagement: Empirical Evidence from the Insurance Industry in Ghana. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Hernández-García, A.; Urueña-López, A. The Role of Emotions and Trust in Service Recovery in Business-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zairah, A.; Rahim, N.; Maarop, N. A systematic literature review and a proposed model on antecedents of trust to use social media for e-government services. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, B.; Zhou, W. What determines customers’ continuance intention of FinTech? Evidence from YuEbao. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. An Empirical Study of Home IoT Services in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of the Usage Experience. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Roderick, S.; Davies, G.H.; Clement, M. Risk, trust, and compatibility as antecedents of mobile payment adoption. In Proceedings of the Adoption and Diffusion of Information Technology, Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2017; Volume 34, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M.E. Improving customer satisfaction of a healthcare facility: Reading the customers’ needs. Benchmark. Int. J. 2019, 26, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hamid, I.K.; Shaikh, A.A.; Boateng, H.; Hinson, R.E. Customers’ Perceived Risk and Trust in Using Mobile Money Services: An Empirical Study of Ghana. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2019, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, L.; Al-Karaghouli, W.; Weerakkody, V. Analysing the critical factors influencing trust in E-government adoption from citizens’ perspective: A systematic review and a conceptual framework. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Amendah, E.; Lee, Y.; Hyun, H. M-payment service: Interplay of perceived risk, benefit, and trust in service adoption. Hum. Factor. Ergon. Man Serv. Ind. 2019, 29, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, G.; Sangl, A. Blockchain Technology and Application Possibilities in the Digital Transformation of Transaction Processes. Forum Sci. Oeconomia 2019, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Grayson, K. Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, G.; Den Hartog, D.N. Measuring trust inside organizations. Pers. Rev. 2006, 35, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyn, G. The Service Sector of a Knowledge-based Economy—A Comparative Study. Oeconomia Copernic. 2013, 4, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcknight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. The Impact of Initial Consumer Trust on Intentions To Transact With A Web Site: A Trust Building Model. J. Strateg. Inform. Syst. 2002, 11, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Romeika, G.; Kauliene, R.; Streimikis, J.; Dapkus, R. ES-QUAL model and customer satisfaction in online banking: Evidence from multivariate analysis techniques. Oeconomia Copernic. 2020, 11, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Weerakkody, V. E-government adoption: A cultural comparison. Inform. Syst. Front. 2008, 10, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Huang, H.Y.; Yen, C.H. Antecedents of trust in online auctions. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Srivastava, S.C.; Theng, Y.L. Evaluating the role of trust in consumer adoption of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.; Ostrom, A.L.; Roundtree, R.I.; Bitner, M.J. Self-service technologies: Understanding customer satisfaction with technology-based service encounters. J. Market. 2000, 64, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, P. The Importance of Trust in Electronic Commerce. Internet Res. Electron. Netw. Appl. Policy 1998, 8, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and Electronic Government Success: An Empirical Study. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, P. Trust in web-based electronic commerce security. Inform. Manag. Comp. Sec. 1998, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lu, Y. Determinants of trust in e-government. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 10–12 December 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Five Forces Transforming Transport & Logistics, Trend Book. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/pdf/publikacje/2018/transport-logistics-trendbook-2019-en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Mangiaracina, R.; Perego, A.; Seghezzi, A.; Tumino, A. Innovative solutions to increase last-mile delivery efficiency in B2C e-commerce: A literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 901–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabinac, M. Innovative solutions for a last-mile delivery. In Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific Conference Business Logistics in Modern Management, Osijek, Craotia, 15 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Ferrand, B.; Roberts, M. The last mile of e-commerce: Unattended delivery from the consumers and eTailers’ perspectives. Int. J. Electron. Market. Retail. 2008, 2, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenezini, G.; Lagorio, A.; Pinto, R.; DeMarco, A.; Golini, R. The Collection-And-Delivery Points Implementation Process from the Courier, Express and Parcel Operator’s Perspective. IFAC-Pap. Online 2018, 51, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, S.; Wei, J. Consumer’s intention to use self-service parcel delivery service in online retailing: An empirical study. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, J.; Ejdys, J.; Halicka, K.; Nazarko, L.; Kononiuk, A.; Olszewska, A. Structural Analysis as an Instrument for Identification of Critical Drivers of Technology Development. Procedia Eng. 2017, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logistics Trend Radar. Delivering Insight Today. Creating Value Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.logistics.dhl/content/dam/dhl/global/core/documents/pdf/glo-core-trend-radarwidescreen.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Mardani, A.; Jusoh, A.; Halicka, K.; Ejdys, J.; Magruk, A.; Ahmad, U.N.U. Determining the utility in management by using multi-criteria decision support tools: A review. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2018, 31, 1666–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Integrating trust and personal values into the Technology Acceptance Model: The case of e-government services adoption. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2012, 15, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, D.; Hussin, N. Forecasting patronage factors of Islamic credit card as a new e-commerce banking service: An integration of TAM with perceived religiosity and trust. J. Islam Mark. 2016, 7, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Rana, N.P.; Tamilmani, K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining adoption of mobile internet in Saudi Arabia: Extending TAM with perceived enjoyment, innovativeness and trust. Technol. Soc. 2018, 55, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.L.; Ferreira, J.B.; Freitas, A.S.D.; Rodrigues, J.W. The effect of trust in the intention to use m-banking. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2018, 15, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.M.; Ahmad, K.; Singh, D. Investigating the effect of information systems factors on trust in E-government initiative adoption in Palestinian public sector. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 5, 3865–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaghier, H.M.; Hussain, R. Conceptualization of trust in the e-government context: A qualitative analysis. In Active Citizen Participation in E-Government: A Global Perspective; Manoharan, A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 528–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. Internet based patient physician electronic communication applications: Patient acceptance and trust. E-Serv. J. 2007, 5, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.; Fang, Y.; Ramesy, E.; Mccole, P.; Ibboston, P.; Compeau, D. Understanding online customer repurchasing intention and the mediating role of trust: An empirical investigation in two developed countries. Eur. J. Inform. Syst. 2009, 18, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, R.K.K.; Lee, M.K.O. EC-trust (trust in electronic commerce): Exploring the antecedent factors. In Proceedings of the Fifth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 13–15 August 1999; Haseman, W.D., Nazareth, D.L., Eds.; Omnipress: Madison, WI, USA, 1999; pp. 517–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M.H.; Chang, C.M.; Chu, K.K.; Lee, Y.J. Determinants of repurchase intention in online group-buying: The perspectives of DeLone & McLean IS success model and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakkody, V.; Irani, Z.; Lee, H.; Hindi, N.; Osman, I. Are UK citizens satisfied with e-government services? Identifying and testing antecedents of satisfaction. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2016, 33, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesca, S.E. Understanding trust in e-government. Eng. Ecol. 2009, 63, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuttur, M. Overview of the Technology Acceptance Model: Origins, Developments and Future Directions. Work. Pap. Inform. Syst. 2009, 9, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurfal, M.; Arifoglu, A.; Tokdemir, G.; Paçin, Y. Adoption of e-government services in Turkey. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New and-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.B.P.; Wan, G. Including Subjective Norm and Technology Trust in the Technology Acceptance Model: A Case of E-Ticketing in China. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2010, 41, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hujran, O.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Chatfield, A.; Migdadi, M. The imperative of influencing citizen attitude toward e-government adoption and use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, S.K. Investigating Postadoption Utilization: An Examination into the Role of Interorganizational and Technology Trust. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2007, 53, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F.; Carter, L. Trust and risk in e-government adoption. J. Strateg. Inform. Syst. 2008, 17, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables, 1st ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Konarski, R. Modele Równań Strukturalnych, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire, C. A mixed methods empirical exploration of UK consumer perceptions of trust, risk and usefulness of mobile payments. Int. J. Bank Market. 2017, 35, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simarmata, J.; Keke, Y.; Silalahi, S.A.; Benková, E. How to establish customer trust and retention in a highly competitive airline business. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 16, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpilko, D. Foresight as a tool for the planning and implementation of visions for smart city development. Energies 2020, 13, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trust in Service Definition | Trust Measurement Scale | Service Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Customer perceptions of service representative honesty, integrity, and ethical standards [58] | Service provider:

| Health insurance, management consulting, telecommunications, travel industry service providers |

| Trust in the community of sellers, is defined as the buyer’s beliefs that sellers in the online marketplace (the community of sellers) will behave fairly (benevolence), capably (competence), and ethically (integrity) [77] | Sellers:

| Online auctions |

| Trust is defined from two perspectives: trust in a mobile service provider and trust in technology facilitated by the mobile service provider [69,78] | I trust mobile payment systems as they are:

I trust mobile payment systems. | Mobile payments |

| Authors distinguished two categories of trust: economy-based trust and service provider trust [67] | I trust that mobile money service providers will:

| Mobile money service |

| Trust in an online vendor as beliefs which include integrity, benevolence, ability, and predictability [63,79] | The online vendor:

| Online shopping |

| Three factors are proposed for building consumer trust in the vendor: structural assurance (i.e., consumer perceptions of the safety of the web environment), the perceived web vendor reputation, and the perceived website quality [74] | The structural assurance of the web:

| Legal advice services |

| Constructs | Ident. | Items | Mean | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The usefulness of courier services [109,110,111,112] | U1 | Thanks to courier services, I can purchase a product in an online store faster. | 5.93 | 0.856 |

| U2 | Courier companies ensure the secure delivery of products purchased from the online store. | 5.46 | ||

| U3 | Courier companies deliver products purchased from the online store to a place convenient for me. | 5.71 | ||

| U4 | Using courier services when shopping online improves my living/working conditions. | 5.70 | ||

| Ease of use of courier services [94,109,111,113,114,115] | EU1 | I easily learned to use courier services when shopping online. | 6.26 | 0.848 |

| EU2 | The tools enabling the use of courier services when shopping online are simple and understandable. | 6.07 | ||

| EU3 | I do not see any problems in using courier services when making purchases via the Internet. | 5.85 | ||

| Trust in courier services [23,107,115,116] | T1 | I trust courier companies to use their services when shopping online. | 5.27 | 0.929 |

| T2 | I trust the technical solutions of courier companies related to shopping online. | 5.33 | ||

| T3 | I believe in the reliability of courier services when shopping online. | 4.92 | ||

| T4 | I am confident that I can rely on the services of courier companies. | 4.87 | ||

| T5 | Courier companies take care of my best interests. | 4.40 | ||

| Perceived Service quality | SQ | The overall level of assessment of the service quality provided by courier companies. | 3.70 | n.a. |

| The future intention to use [78,111,112,115,116] | FI | I intend to use courier services more often. | 4.81 | n.a. |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis (H1).The ease of use of courier services has a strong and positive influence on trust in courier services. | 0.189 | 0.064 | 2.949 | ** | Support |

| Hypothesis (H2).The usefulness of courier services has a strong and positive influence on trust in courier services. | 0.773 | 0.048 | 16.226 | *** | Support |

| Hypothesis (H3).The trust in courier services has a strong and positive influence on perceived courier service quality. | 0.279 | 0.016 | 17.245 | *** | Support |

| Hypothesis (H4).Perceived courier service quality has a strong and positive influence on the future intention to use courier service. | 2.888 | 0.193 | 14.962 | *** | Support |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ejdys, J.; Gulc, A. Trust in Courier Services and Its Antecedents as a Determinant of Perceived Service Quality and Future Intention to Use Courier Service. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219088

Ejdys J, Gulc A. Trust in Courier Services and Its Antecedents as a Determinant of Perceived Service Quality and Future Intention to Use Courier Service. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219088

Chicago/Turabian StyleEjdys, Joanna, and Aleksandra Gulc. 2020. "Trust in Courier Services and Its Antecedents as a Determinant of Perceived Service Quality and Future Intention to Use Courier Service" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219088

APA StyleEjdys, J., & Gulc, A. (2020). Trust in Courier Services and Its Antecedents as a Determinant of Perceived Service Quality and Future Intention to Use Courier Service. Sustainability, 12(21), 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219088