1. Introduction

The ongoing global financial crisis—as well as the forthcoming crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic—coupled with mounting environmental problems, sends out strong signals on the limits of the “business-as-usual approaches”, spearheaded by orthodox economics. These approaches appear now to be limited in terms of their ability to sufficiently understand and explain complex social processes and interdependencies. Providing responses that can go beyond the standard economic policy prescriptions for resolving the multifaceted crises of today and ensure sustainable economic development are more urgent than ever. This requires bespoke solutions tailored to address the particular characteristics, needs and institutional capacities of each case separately, as well as a fresh look at current economic questions.

When we revisit the majority of the attempts made since the 1990s to rectify problems of dysfunctional states, however, we can observe a persistent pattern of the offered remedy: enforcing institutional change. This is manifested in shifting programmes of international financial aid to supporting institutional building and reforms and is adopted by international development organisation such as the World Bank, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and International Monetary Fund (IMF). In this frame, the importance of institutions for successful reforms is widely recognised and institutional change emerged as the instrument to resolve acute problems developing countries have been facing [

5]. However, institutions have been consistently approached in a rather oversimplistic manner: the problems of Nigeria and Senegal, for example, were suddenly transformed into the problem of their not having the same institutions as Norway and Sweden (ibid). According to this line of reasoning, as the latter have x institutions in place and they are wealthy, the only thing the former needs to do is to import the same institutions and they will also become rich, and fully capable of responding to any crisis (ibid).

The reliance of international organisations on institutional changes and reforms as the remedy for “fixing” dysfunctional economies in the developing world (based on a set of economic policy prescriptions, known as the “Washington Consensus”, as codified by by John Williamson in 1990) coincided with two events of global importance: the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the debate on conflicts and natural resources.

The collapse of the Soviet Union (1988–1991) was indeed a shock of epic proportions for the entire post-socialist world and beyond. Whole countries experienced traumatic socio-economic and political shocks, threatening the very existence of their societies [

6]. Agriculture, the main economic activity in many Soviet Republics until 1991, suffered particularly from these shocks: the diminishing support for water infrastructure was coupled with grazing practices closely resembling a tragedy of the commons situation as illustrated by Hardin [

7] and the disappearance of a vast Soviet market for agricultural products [

8,

9]. In this transitional frame there has been a heated academic debate on how the post-socialist transition and the occurring institutional change should be conceptualized and what the effects of transforming highly centralized states to decentralized market-oriented economies would be on the economy, society and the environment of the countries [

10,

11].

Almost in parallel with these processes, environmental stress was identified by the United Nations’ (UN) “Our Common Future” as a potential cause of violent conflict. Since the early 1990s, research on the causal links between conflicts (understood broadly as a state of opposition between different groups with contesting ideas and interests) and natural resources has gained momentum. The end of the Cold War gave a new meaning to securitisation, as water, energy and climate change have been increasingly formulated in terms of security concerns by researchers and policymakers alike [

12]. Environmental governance and environmental security emerged as prominent concepts, implicitly or explicitly investigating the linkages between scarce natural resources and conflicts, focusing especially at the international level. As economies in transition, many post-socialist and post-colonial countries are particularly vulnerable to climatic and non-climatic stresses that are likely to exacerbate regional vulnerability to the impacts of climatic changes like aridity and desertification, further reducing adaptive capacity due to the allocation of diminishing resources to competing needs [

8]. Climate change-related environmental risks, such as droughts and floods, land-use changes, food and water insecurity, have been perceived as a threat multiplier and a ticking bomb that could trigger conflicts (from local to international level in regions vulnerable to climate change [

13]. Recent research identifies a number of emerging or long-lasting disputes related to natural resources that are threatening to descend into full-blown conflict [

14,

15,

16].

In spite of the introduced institutional reforms aiming at transforming the newly emerging or chronically dysfunctional economies, resolving rapidly emerging conflicts and filling the institutional vacuum left by the fall of the Soviet Union, many countries still fail to meet the expectations. Perhaps counter-intuitively, it has been observed that throughout the process of transition and the institutional reforms initiated in the 1990s, alternative institutional arrangements that should have allowed for a sustainable management of natural resources and economic development have either performed poorly or have actually had results opposite to those intended [

6]. Hence, introduced reforms across the globe have been criticised by both scholars and policy makers (e.g., [

17,

18,

19]) as being context-insensitive and largely unaware of the highly complex interdependencies between human and natural systems. In the words of Noam Chomsky: “[…] right before the Arab Spring, Egypt was a kind of poster child for the World Bank and the IMF: the marvelous economic management and great reform. The only problem was for most of the population it was a kind of like a blow in the solar plexus: wages going down, benefits being eliminated, subsidized food gone and meanwhile, high concentration of wealth and a huge amount of corruption” [

20]. Interestingly, the very same organisations advocating for the particular reforms, are often critical towards their own prescriptions: “The central message […] is that there is no unique universal set of rules […] [W]e need to get away from formulae and the search for elusive ‘best practices’” (p. xiii, [

21]).

Why then do the same mechanisms to promote institutional reforms persist? How can we explain such then the persistence despite contradictory evidence? Why not focus instead, on those processes accounting for complex interdependencies of human existence enabling creative institutional solutions?

A very important part of the answer to these questions lies in the basic thesis of this largely conceptual article: in order to escape the business-as-usual” prescriptions a different, more pluralistic position on institutional research must be assumed. Motivated by institutional failures in transformative contexts, and hoping to provide some food for thought for the readers and other authors in the special issue on ”Natural Resources Management and Conflicts in the context of Sustainability Transformation”, I approach the link between institutional change (or “reforms” according to the mainstream narrative) and conflict through the hermeneutical lens of Institutional Economics (IE). Although the key concepts utilised in the current paper fall into the realm of IE, they are further complemented with insights from political science. I adopt a diagnostic approach and investigate institutional research on transformative contexts, with a particular focus on institutional change and associated conflicts by drawing some empirical examples and implications from past-cases in the post-socialist and post-colonial world. Following the tradition of Commons [

22], Bromley [

23] and Vatn [

24] I approach institutions as social and as purposeful constructs—conventions, norms, formally sanctioned rules—functioning as enablers of realms of choice that facilitate coordination amongst people. In a broader sense the paper touches a number of key issues in IE, broadly contributing to the discussion on why environmental problems that may be primarily

non-economic should be approached in narrow, orthodox economic terms that fail to examine issues pertinent to public policy and to establish harmony as a vital social need [

25].

From this perspective, the main aim of the paper is to explore to what extend certain propositions and concepts utilised by institutional economists might be useful to explain why conflicts persists despite institutional reforms explicitly or implicitly introduced to resolve them. It should be noted that the specific objectives of the paper cannot be viewed separately from the thematic core of the special issue and are intended to: (i) provide a set of common premises as a basis for discussion; (ii) provide precise terminology; (iii) assist the authors developing relevant research questions; and (iv) identify gaps in the literature and promising areas for further research.

It is crucial to highlight that conflict is viewed here as an important contextual factor under which institutional processes take place and as a framing condition for the (non)cooperative strategies adopted by involved actors, ultimately influencing the success of introduced institutional changes. From this perspective, the present work also contributes in a rather exploratory manner to the investigation of proposed associations between contextual factors (attributes of actors and resources in question, their socio-political context, and the surrounding environment), framing conditions (characteristics of existing or potential conflict) and outcomes of institutional changes, providing plausible answers on why the latter fails to deliver.

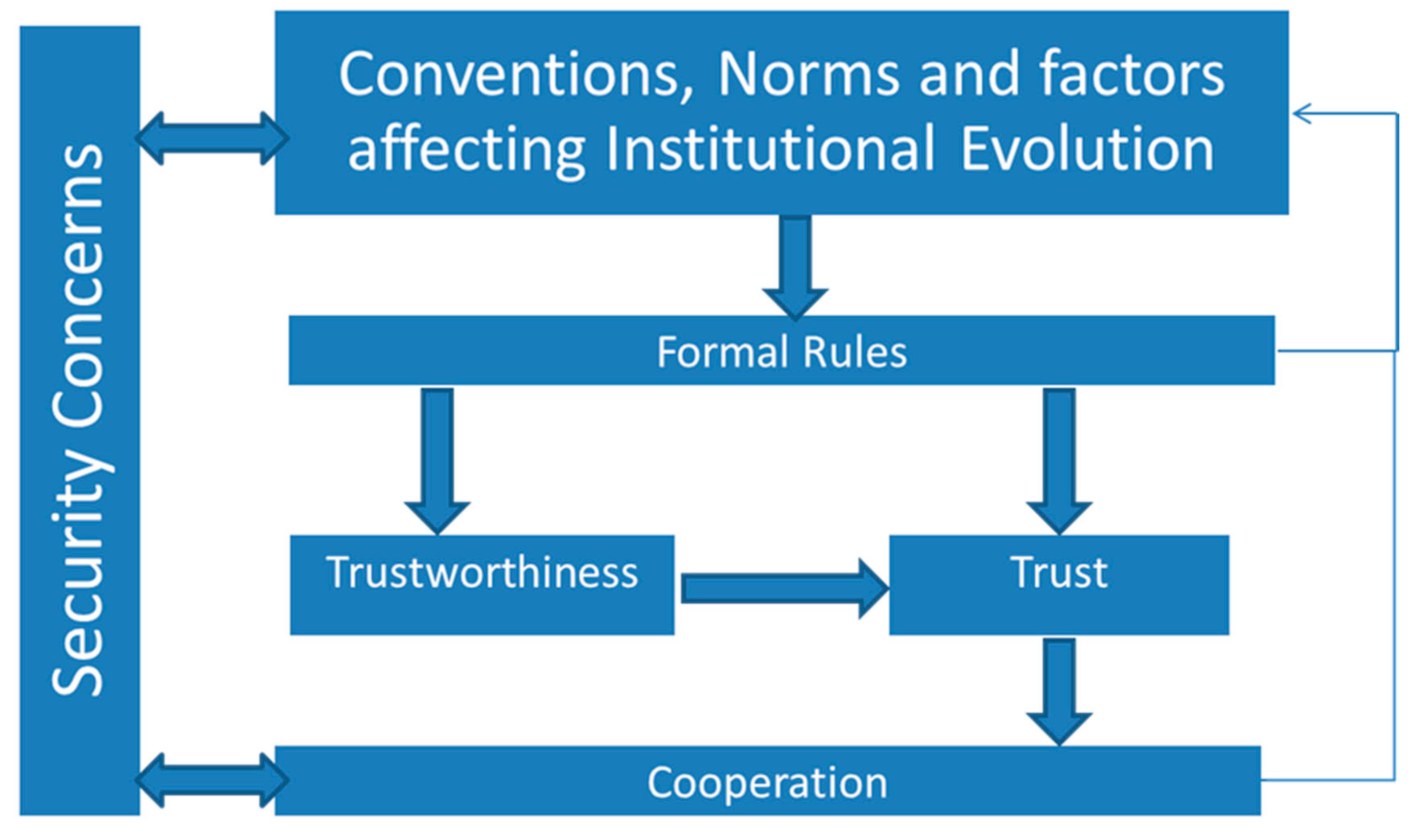

The Trust, Institutions, Security and Cooperation framework, as depicted in

Figure 1, is based on Farrell and Knight’s [

26] Trust, Institutions and Institutional Change framework, which relies heavily on Knight’s [

27] distributive and bargaining theory investigating how the change of informal institutions is affected by changes in power asymmetries and their distributional consequences. Within my framework, however, special consideration was given to the role of conventions, norms, other factors (like

ideas) and formal rules in trustworthiness and trust, in relation to interdependent cooperative outcomes and security concerns—implicitly including conflicts of varying stages of intensity.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 of the paper briefly reviews key literature on institutional economics in an attempt to advance our understanding of different conceptualisations of institutions. It underlines the main arguments of the literature within each institutional school of thought and summarises the key attributes of each. In

Section 3, the article summarises and critically assesses the current knowledge of institutional change especially in relation to conflicts in Common Pool Resources (CPRs), identifying several key concepts. In this section past cases are revisited and regional examples are illustrated in an attempt to investigate those key concepts that might explain the failure of institutional structures, emergence and change.

Section 4 revisits Polanyi’s Great Transformation and introduces Blyth’s five hypotheses on institutional change, drawing some lessons from contemporary processes and detailing several conditions under which institutions considered as a response to social-environmental issues fail to deliver what they promise.

Section 5 concludes with some tentative lessons learned and the most promising topics for the future scientific agenda.

The reader should be aware that this paper is not intended to provide an exhaustive review of institutionalist research and conflicts, solidify any findings and tightly connect key propositions to the concept of transformations. She should always keep in mind instead the fundamental limitations of a guiding paper, especially in terms of the analysis and limited empirical evidence, as well as the omission of some key concepts in institutional economics, which fall outside the scope of the special issue.

2. Defining Institutions

According to Bromley and Anderson [

17], the fluidity and obscurity of the term “institution” as used by organisations like the World Bank as well as economists and policy makers explains why policies aiming at institutional change largely fail to meet their target: as long as institutions means everything and thus nothing, they simply cannot offer a conceptual framework and a useful instrument to design development programmes and succeed in responding to crises, not to mention to address tensions and resolve conflicts. Although her points of reference are different, Ostrom [

28,

29] seems in agreement with Bromley and Anderson [

17] when arguing that each group struggling to build an institution works under the handicap of being largely unaware of knowledge about how institutions succeed and fail. This is a rather old, yet unresolved problem, institutional economics tried to address.

Although the term was introduced in 1919 by Walton Hamilton [

30], Thornstein Veblen and John R. Commons are widely considered the fathers of institutional economics (although the latter was not considered as such until the publication of his seminal work the

Foundations of Capitalism [

22]. The former posed the basic questions and set the fundamental conceptual basis of institutional economics as early as the late 19th century—inspiring others—while the latter developed the conceptual framework and study institutions in depth [

31,

32]. Wesley Mitchell, Walter Stewart, John Clark and Walton Hamilton were deeply engaged in the development of institutional economics in this early phase and largely contributed towards its acceptance as a distinctively different new branch of economics [

33]. As a result, institutional economics dominated US academia after World War I [

34].

Veblen developed four basic theses that differentiate institutional from the also emerging neoclassical and Marxist economics of the time [

35]:

Social structures are completely dependent on individuals. Individuals and their actions can, intentionally or not, form, reproduce, change, confirm, re-affirm, transform or destroy social structures. Without individuals, social structures would not exist.

In the same way as social structures depend on individuals, individuals are completely dependent on social structures. This creates interdependencies and interactions between the two, resulting in evolutionary economic behaviour.

The methodological individualism central to neoclassical economics is rejected, as social structures cannot be fully explained in individualistic terms.

The methodological collectivism typical for Marxist economics is equally rejected, as interactions between individuals and purely individualistic behaviour are not insignificant but, rather, interdependent with the collective.

Despite its wide acceptance, however, proponents of institutional economics failed to produce mathematical and econometric models, increasingly popular among their neoclassical rivals. This fact, combined with rapid changes in the US and in the social sciences as a whole during the interwar years—the most notable events of global significance included the Wall Street crash, the consequent financial crisis, and the establishment of the Soviet Union—made the hermeneutic and methodological approaches of neoclassical economics more attractive to the economic theorists and politicians of the western world [

35]. In the discourses of that time, we notice the paradox that neoclassical economists first accepts fundamental claims developed within institutional economics (like the importance of institutions, like in today’s example of Nigeria and Senegal) only to reject institutionalism as a whole with the argument of being unscientific or beyond the scientific boundaries of economic theory (e.g., [

36]).

In this frame it should be noted that one of the main shortcoming of this first wave of “old” institutionalists since Veblen was that there has been a failure to agree upon and to develop a systematic theoretical core addressing the very heart of Classical Institutional Economics (CIE): what exactly institutions are [

37].

As early as 1931, Commons emphasised the difficulty of defining institutions, noting that:

Sometimes an institution seems to mean a framework of laws or natural rights within which individuals act like inmates. Sometimes it seems to mean the behavior of the inmates themselves. Sometimes anything additional to or critical of the classical or hedonic economics is deemed to be institutional. Sometimes anything that is “economic behavior” is institutional. Sometimes anything that is “dynamic” instead of “static,” or a “process” instead of commodities, or activity instead of feelings, or mass action instead of individual action, or management instead of equilibrium, or control instead of laissez faire, seems to be institutional economics .

Such difficulty still appears to persist today within institutional economics, where dozens of different definitions seem equally acceptable and popular amongst institutionalists. Hodgson [

35] remarks that, although the use of the term “institutions” has been constantly increasing year by year, a commonly accepted definition has yet to be found.

For CIE, institutions are purposefully constructed by the collective with the aim of altering interactions between members of a certain situation. From this perspective, the collective is important and institutions are seen as enablers of realms of choice rather than constraints. Commons [

22] defines institutions as legal relations (a) between individuals and (b) between individuals and the state. Bromley highlights the coordinating character of institutions as “rules and conventions of society that facilitate coordination among people regarding their behavior” (p. 22, [

23]). Institutions then become the locus of the rule of law.

Following in the tradition of Commons and Bromley, Vatn [

24] sees institutions as socially and purposefully constructed, offering a typology of them according to their form, motivation, distinguishing conventions, norms and formal rules. Institutions thus constitute “the conventions, norms and formally sanctioned rules of a society. They provide expectations, stability and meaning essential to human existence and coordination. Institutions regularize life, support values and produce and protect interests.” (ibid: 60). Conventions (like language) address and simplify simple coordination problems. Norms differ from conventions in terms of their incorporation of values. Norms are socially created and internalised rules to define and support values in a situation with conflict potential. Lastly, formally sanctioned rules combine an act which is either allowed or forbidden with an agent or a system with sanctioning authority. This third category, the formal rules, is referred to by both Commons [

22] and Bromley [

38] as legal relations having the purpose of creating order and resolving conflicts. These legal correlates define what individuals “must or must not do (duty), what they may do without interference from other individuals (privilege), what they can do with the aid of the collective (power) and what they cannot expect the collective to do in their behalf (no right)” (p. 43, [

23]). Hodgson [

35,

39] further highlights the role of institutions as social constructs, defining them as systems of established and embedded social rules that structure social interactions. Institutional arrangements influence governance structures, shape the economy and affect public awareness and civic engagement.

The New Institutional Economics (NIE) was introduced as a term by Oliver Williamson [

40], but explained in terms of fundamental principles by Ronald Coase in the 1960s [

41]. Elinor and Vincent Ostrom, working on the main concepts of public and metropolitan governance during the time, also contributed to the revival of NIE by developing the key concepts of polycentricity [

42]. Polycentricity is defined as “many centers of decision making which are formally independent of each other” (p. 831, [

42]) but in practice they are functionally interdependent. This proposition radically shifted the paradigm of viewing the fragmentation of authority and overlapping jurisdictions as “chaotic” and as the principal source of institutional failure [

43] and challenged well-established principles of political theory while paving the way for the future work of Elinor Ostrom on institutional economics and the study of the commons.

NIE largely adopts the definition of institutions given by North, for whom they “are the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (p. 3, [

44]). Institutions are, then, seen primarily as external constraints—instead of enablers—for individuals whose goal is to maximise their utility. Brousseau et al. [

45] make a clear distinction between formal and informal institutions, arguing that the latter are created spontaneously, whereas the first are the result of design. Hodgson agrees with NIE about the importance of informal rules, but opposes a sharp distinction between formal and informal institutions, claiming that formal institutions always depend on extra-legal rules and inexplicit norms and that “ignored laws are not rules” (p. 6, [

37]). He argues that such sharp distinctions can lead to confusion: “if formal rules mean legal, then it is not clear whether ‘informal’ should mean illegal or non-legal” (ibid). He suggests distinguishing between explicit and tacit, designed and spontaneous institutions in order to be sufficiently clear. Such distinctions can be made according to the mechanism of rule enactment (i.e., self- and external enforcement), to their formalisation (i.e., legal, non-legal and explicit), or to the mechanisms of rule-making (i.e., between endogenous and exogenous crafting of institutions; ibid).

For the purposes of this paper, rule crafting and the associated concept of trust are relevant [

28,

46]. Of particular importance in transformative contexts is the differentiation between those rules that are exogenously designed (imposed on a community by external actors) or endogenously crafted (resource users participate in the rule-making). Especially when focusing on CPRs like irrigation water, endogenous rules have been observed to perform better than exogenously designed ones; Ostrom [

47], for example, identified the ignoring of endogenous rules as one of the major reasons for the failure of irrigation water systems. According to Ostrom, governments tend to apply blueprint sets of rules and ignore actual rules in use, endogenously developed by communities of resource users [

47]. Ignoring of endogenous rules may have implications for a whole array of problems, from the emergence of informal structures, often defying or even contradicting exogenous rules, to the collapse of whole systems and the emergence of violent conflict [

47]. Indeed the long reliance of development organisations on transplanting exogenously designed institutions in many countries undergoing transformations has largely failed to produce the expected results [

48,

49]. Instead, endogenous rule-crafting can help resource users to overcome appropriation and provision dilemmas in resource-scarce environments. Evidence from Jordan and Cyprus suggests that, given the opportunity, resource users are able to craft their own rules improving the overall performance of the group in terms of investment and revenue, with a parallel improvement of equity in distribution [

50]. These findings are very much in line with a similar study conducted in Vietnam, China and India [

51]. On the other hand, Aslund argues that new institutionalists like North and Williamson who blamed the radical reforms in the post-socialist world for neglecting institutions, were wrong, as in fact the introduced changes sparked endogenous processes that sometimes resulted in rather successful institutional changes [

52].

Trust is an essential cross-cutting element for cooperation, allowing actors to make specific assumptions about each other’s behaviour and decisions, hence tending to reduce uncertainty and complexity. The relationship between cooperation (whether of a bilateral or multilateral, regional or sub-regional nature) and trust holds a prominent place in key interdisciplinary literature [

53,

54], highlighting the role of trust in facilitating cooperation and, thus, implicitly affecting various behavioural outcomes. Although trust is defined in many different ways, Farrell and Knight (p. 8, [

26]) propose a definition of trust as “a set of expectations held by one party that another party or parties will behave in an appropriate manner with regard to a specific issue”. Substantial evidence acquired from research within institutional economics, as well as beyond, demonstrates that social norms prescribing cooperative or trustworthy behaviour have a significant impact on whether societies can overcome obstacles to contracting and collective action that would otherwise hinder their development [

47,

55].

The notion of trust becomes even more relevant in contexts where social cooperation cannot be understood as simple institutional compliance. As Farrell and Knight put it, “Cooperation through compliance with institutional rules in particular social settings affects an actor’s beliefs about the propensity of others to cooperate (their level of trustworthiness) in similar settings, which affects that actor’s willingness to cooperate at some subsequent point in time in that same social setting” (p. 10–11, [

26]). This situation is very well illustrated in the study by Kasymov and Zikos [

56] where they observe that in the interactions between livestock owners and herders in Kyrgyzstan, shared beliefs concerning the credibility of commitment of herders depend very much on their reputation and the trust that develops over time.

In such a setting, Crawford and Ostrom [

57] make a useful distinction between institutions as “equilibria”, “norms” or “rules”. As equilibria, institutions create stability through a common understanding of actors’ individual preferences at a given time and optimise behaviour to achieve the best outcomes for them. This fixed pattern of behaviour is then understood as an institution. Institutions, understood as norms, refer to shared beliefs among members of a group, creating an interaction pattern of behaviour based on what is and what is not acceptable within it. Institutions function as rules, on the other hand, when “many observed patterns of interactions are based on a common understanding that actions inconsistent with those that are prescribed or required are likely to be sanctioned or rendered ineffective if actors with the authority to impose punishment are informed about them” (p. 583, [

57]). Distinguishing norms from rules in accordance with Crawford and Ostrom [

57], Vatn ([

24]) notes, however, that the absence of a formal sanctioning mechanism does not mean that breaking norms necessarily goes without punishment. The internalisation of norms, and the values inherited in them, may cause a sense of guilt so strong that, in practice, the effects on behaviour can be equal to those of a formal sanctioning mechanism.

Combining the importance of beliefs and the debate on formal or informal, endogenous or exogenous institutions, Aoki [

58] proposes a conceptualisation of institutions as ‘shared beliefs’ among actors and argues that with such an understanding all institutions are ultimately endogenous. His concept can be referred to as ‘behavioural beliefs’, in the sense of expectations regarding the behaviour of others. In that sense, it is not decisive whether an institution is a law or a custom, formal or informal; what makes it effective is the shared belief in the institution. In a related line of analysis, institutions are seen as rules-in-use and common knowledge [

47]. These can be in accordance with the legal system or contradicting it; it is the rules in use that de facto regularise specific situations. In a system governed by the rule of law, formal laws and rules in use are closely aligned and mutually enforced. However, an incomplete rule of law often makes rules in use difficult to observe.

The discussion on the very meaning of institutions and some key concepts as seen in this section becomes indispensable to understanding better the current institutional status of dysfunctional economies of today, be it from the post-socialist, post-colonial or even post-eurocrises world. In this context, certain norms became the rules of the game in the pre-Soviet era and survived the rise and fall of the Soviet Union [

59,

60]. Similarly, many Soviet-era norms survived the transition from state socialism to a market economy [

61]. An example of the Soviet legacy in Tatjikistan and Georgia for instance is the practice of using

kompromat (compromising material) as means of control to enable the breaking of laws [

62]. In this frame, institutional structures introduced in the post-Communist world are often inconsequential, while traditional behavioural patterns coexist with (and even contradict) new institutions [

61,

63]. Another study by Ibele et al. [

50] further support these findings by drawing linkages between Jordan and Cyprus as seen in the importance of traditions, beliefs, values and even shared religious imaginings (between Christians and Muslims) as influential factors during the process of institutional crafting. Such norms and conventions might actually shape behaviour with regard to decisions on water allocation, distribution, rule compliance, investment and free-riding considerably more than the formal institutions in place.

The following section focusses on the core concept of the paper—institutional change—viewed from the angle of its inherited conflict-inducing and/or conflict-resolving ability.

3. Changing Institutions, Creating Conflicts?

Institutional economics, as well as a great number of other disciplines dealing with the “institutions-history-social structure nexus” instead of the “rationality-individualism-equilibrium” typical in mainstream economics, view conflict as a function of many factors, not as a purely determined result of competition. Based on a literature review, the full extent of which goes beyond the scope of this paper, I argue that there is a general consensus, regardless of the disciplinary departure point, that the role of institutions has been widely recognised in the discussion on natural resources and conflicts [

64,

65,

66]. This should not come as a surprise to a reader familiar with institutional economics, as within all definitions found in the rich literature, the notion of institutions as interaction-coordinating mechanisms between individuals and groups to avoid conflicts is either implied [

44,

67] or integrated as a component of the definition [

22,

24,

37].

The conventional—and flawed, yet widely accepted by policy makers—view of institutional change is that it is either in the interest of economic efficiency, or it merely redistributes income [

68]. For the purpose of this paper, institutional change is understood as the process of creating an institution for (i) a concern where no institution had previously existed (i.e., where the concern is new, such as with for instance climate change), (ii) the replacement of an existing one that does not fulfil its purpose anymore or (iii) the adjustment of an existing institution to changing social or bio-physical conditions. Theories of institutional change address the questions of how and why the institutional status quo changes, approaching these questions through different perspectives. Some theories start from the assumption that change is spontaneous or designed, while others mark a distinction between whether it is initiated by the “top” or the “bottom” of a hierarchy, each one dealing with different challenges and presenting different strengths [

69].

One ground upon which institutional change is predicated is that of responding to crisis, adapting to which requires new institutions. Vatn [

70,

71], however, cautions against the possibility that crisis might legitimise changes that would otherwise not be accepted. Such a lack of acceptance might “legitimise” in turn the emergence of rules contradicting the newly introduced crisis-response institutions. Haller and Merten [

72] show how economic crises in Zambia influenced institutional change, and how using the notions of ideology and modernity modify the bargaining power of actors that in turn use this power to change or maintain institutions that fit to their interests. A similar process has been observed in the post-eurocrisis Mediterranean Europe [

73]. Viewing the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the consequent power-struggle between actors as the ultimate crisis in its satellite states, we can easily reflect on how weak or inconsistent the legitimisation of new institutions has often been.

With regard to possibilities of institutional change, it seems relevant at this point to highlight that rules, according to Ostrom [

47], are organised in multiple layers:

operational rules regularise everyday activities and are easy to change;

collective choice rules need a collective effort and a medium-term time horizon to be changed; finally,

constitutional choice rules are much more difficult to change, such as with the constitution of a country (

ibid). For irrigation systems, for example, institutions regulating processes like the clearing of a canal or monitoring water allocation appear on the operational level, such as when Kyrgyz farmers meet regularly to discuss such processes [

74]. At the collective choice level, the apportioning of water amongst farmers might be regulated in meetings, before the beginning of the irrigation season such as when Uzbek water user associations ensure reliable distribution of water amongst farmers [

75]. At the constitutional level, de facto property rights regarding water might be decided at the central level, according to long-term national (or even international) agricultural policies, like the Water Framework Directive or the Common Agricultural Policy in the European Union (EU) [

73]. As several studies in which the author has been involved have shown, imposed changes often target the constitutional choice level, ignoring operational and collective choice rules often surviving from pre-colonial, pre-European or pre-socialist times [

50,

73,

74,

76,

77]. This might partially explain the limited success of internationally supported and technologically innovative development projects in transformative contexts, being encapsulated by dysfunctional operational and collective choice rules [

78].

Focusing on the conflicts directly related to newly introduced or changed institutions that affect de facto or de jure property rights, Ide ([

79]) distinguishes between two hypothesised causal mechanisms: (i) either locals become increasingly discontented due to their exclusion from the use of scarce resources or (ii) powerful actors use violent means in order to enforce changes in existing property regimes. In both proposed causal mechanisms, commercialisation processes, privatisation and state intervention play a major role. Commercialisation, understood as the increasing exchange of natural resources in international markets rather than within local systems of reciprocity and subsistence, might lead to increased goods prices, resource scarcity or enclosure of resource-rich areas in Africa and Latin America [

79,

80,

81]. Similarly, privatization—defined as the transformation of a resource from an open access, common or public good to a private good—brings considerable alternation of the bundles of rights of previously authorised resource users [

79,

81,

82]. Finally, state interventions, regardless of their aim, might also alter property rights, restricting access to, or use of, natural resources or even dislocate people from their homes, as occurred in Peru [

79,

83]. These causal mechanisms are particularly intense in post-socialist settings [

84,

85]. Sikor [

86] for instance, distinguishes a growing discontent in Eastern and Central European post-socialist countries noticing that those with sufficient power have appropriated resource benefits and control over natural resources well beyond the provision of national legislation, while also ignoring associated obligations and duties. Furthermore, a main trend that characterises the management of the commons in many post-Soviet as well as post-colonial states is the gradual privatisation of natural resources either collectively or state-owned in the past [

87]. Comparative qualitative empirical studies related to the commons around the globe illustrate that this change increases competition between users as the rules of the game become unclear and it paves the way for mistrust and conflicts over resources in African floodplains [

80]. Such change is part of a broader historical change since colonial times in many parts of the world and of structural adjustments pushed by market forces. As a result, and referring to Ide’s hypothesised causal mechanisms ([

79]), imposed institutional change aiming at releasing market forces that would (i) achieve greater disembeddedness of the economy; (ii) turn of resources, land and people into “fictitious commodities”; and (iii) transform the interactions and interdependencies between social and ecological systems, were introduced as proper responses to growing crises, whereas they might actually have contributed to or even initiated them.

Paavola [

88,

89] conceptualises emerging conflicts directly related to the hypothesised causal mechanisms as situations where different groups have conflicting interests regarding the use (or protection) of natural resources (although it is irrelevant whether this conflict will come into the open or not), due to the interdependencies created by the various characteristics of the resource and its users. Such characteristics might drastically change due to the introduction of new rules. A typical example of such situations is the Kumtor gold mine in Kyrgyzstan. On one hand, Kumtor alone contributed around 10% to the GDP of Kyrgyzstan in 2017 [

90]. On the other hand, this is maybe the most contested project in the country, loaded with conflicts between “environmentalists” and “developmentalists” [

19]. The former argue that the project produces revenue that it is rarely used for the development of the local communities which suffer most from the degradation of the natural resources around the mine [

91]. The latter counter-argue that Kumtor is indispensable for the economy of Kyrgyzstan, while environmental concerns are gradually addressed by the mining company [

92,

93]. In this frame, institutional economics becomes highly relevant for unpacking the dimensions of such conflicts as they indeed put considerable emphasis on the interdependencies between social and ecological systems, especially in terms of externalities. Although when focusing on conflicts, transaction costs may also play a major role [

27], interdependencies is the major concern for the purpose of this paper: when the choice of an actor directly or indirectly affects the choice of another, then conflict might emerge. In most cases, interdependent users of a natural resource cannot simultaneously make their choices without contradicting each other [

94], and conflict that might emerge needs to be solved by deciding whose interest will ultimately prevail and to what extent. This mutual exclusion of interests between groups of users and the inability of the state to find compromising, legitimate and widely accepted solutions have tortured the large parts of the world since 1991.

In this context, power considerations of actors related to their interests can play a vital role when policy decisions are made [

95]. When actors intentionally make (or attempt to influence) decisions based on their beliefs about the potential benefits offered by different institutional arrangements, unintended consequences might ultimately prove their predictions wrong [

96]. Furthermore, powerful agents with competing rationalities and diverse interpretations of the common pool resource in question, shape the formation and implementation of new policies [

70,

97]. Muradian et al. ([

98]) argue that the allure of “win-win” solutions and the assorted assumptions result in the production of simple policy tools expected to solve complex policy problems. In other words, policy makers keep pursuing panaceas to problems of overuse or destruction of resources [

99]. Such simplifications however distract policy makers from the real essence of effective rule-making where conflicting interests must be acknowledged, assumptions must be validated, and trade-offs must be faced [

88]. This proposition at least partially explains why successful institutional design in nations undergoing reforms should take into account power relations between higher-level authorities and users or user associations [

100]. These power considerations are, however, further fuelled by introduced market-related mechanisms like induced changes in prices and costs of resources like water, leading in turn to internal changes in the bargaining power of actors, motivating them to transform institutions such as property rights or rules in use for their benefit while in parallel legitimising these changes ideologically [

72,

101]. From this perspective, several studies investigate bargaining processes between pastoralists with asymmetrical power in Central Asia, demonstrating the high interdependence amongst actors with different interests and the importance of the shared beliefs [

56,

102,

103].

All in all, the described process of institutional change and the assorted policy making largely relates to the vision of the engaged actors for the desired state of things in the future. This in turn implies that the emergence of market structures diversifies how concepts like scarcity and access over a resource are articulated across different groups and how they acquire multiple meanings over time [

104]. Emergent social construction is predominant in understanding the design of new institutions and the forms of governance that influence the co-evolution of social and biophysical systems by creating changes in material use, practices and corresponding management challenges [

105,

106].

In many cases it is not only the lack of effective institutional design and delivery combined with inadequate rule enforcement that undermines a successful transition [

15]. The very concept of transformation, as it will be discussed in the next section, precludes a smooth transition, where ideally, functional market economies emerge, Sustainable Development Goals are attained, sustainable use of resources is ensured, while all actors are equally content in an over-optimistic and notional win-win setting.

4. Great Transformations and Some Reflections

In 1944, Polanyi argued that the emergence of the liberal (self-regulating) market structure has led to a characteristic “disembeddedness” of the economy [

107], understood as an economy independent from any social structures. What he described as the Great Transformation (ibid) was the emerging machine-made production in commercial societies and the changing perception of the environment that brought tremendous changes within the European societies of the 19th century. In this context, natural resources as well as human labour are transformed into saleable goods. Polanyi further argued that, alongside the establishment of a market society, people’s economic mentalities changed as well. Decisions based primarily on reciprocity and redistribution were replaced by the notion of economic profit as a central motive for any behaviour in everyday life. Within this framework, resources and land as well as people’s capacity for labour are turned into “fictitious commodities” tradable on markets (ibid). This, in turn, has a direct effect on social relations and “mental infrastructures”.

Although the Western world has undergone several other transformations since Polanyi’s work, it was not until 1972 and “the limits to growth” by Meadows and colleagues that the dominant paradigm of infinite growth was challenged [

108]. Largely informed by Polanyi’s and Meadow’s work, new discourses are emerging today as a growing number of scholars urge that a fundamental change of the growth paradigm is desperately needed. The disciplinary field of Political Ecology and the Degrowth movement, for instance, have been gaining momentum in academic discourses, strongly promoting cooperative behaviour, future-oriented or non-profit economic activities, fair trade, sharing or other real-life experiments, forming what is being called the start of the “new great transformation” [

109,

110].

Contrary to this vision however, primarily agricultural and pastoral societies around the globe have been radically, forcefully and often even violently transformed by changes in the political and socio-economic structures surrounding them [

111,

112,

113]. Although the driving forces for the Great Transformation occurring worldwide radically differ from the situation in 19th century Europe, the mechanisms are similar: market structures are introduced from the West, transforming humans and nature as well as their relationships and interdependencies.

Indeed, over decades or centuries of colonial rule, Western concepts and ideologies regarding natural resource management have radically transformed colonised societies, stripping them of their resources and disrupting pre-existing equilibria between human and natural systems [

114]. Post-colonialism was often followed by enclosure of common and communal farmland, quite similar to what Polanyi observed in 17th-century Britain [

107]. For the nobility or ruling caste, enclosure of large tracts of land was a natural companion to economic progress. But for poor farmers, enclosure led to deprivation and displacement from the commons, beginning the process of disembeddedness. In a very similar way, the enforcement of collectivisation and modernisation reforms under decades of the Soviet regime disturbed existing institutions regulating interactions between social and ecological systems. Then, the aggressive post-Soviet reforms since 1991 have proved Polanyi ([

107]) right: former collective farmers and industrial workers became formally “free” but were now forced to sell their labour in order to earn their livings. This is not to say that Polanyi was advocating for a socialist centralised system. On the contrary, in his later writings he clarified that “any attempt to organize [a group] under a single authority would eliminate their independent initiatives and thus reduce their joint effectiveness to that of the single person directing them from the centre. It would, in effect, paralyze their cooperation” (p. 467, [

115]). In his view the economic “optimum” can neither be derived nor imposed by central authorities but instead the system should be allowed to move in a trial-and-error fashion [

116].In short, Polanyi views institutional change as part of the Great Transformation, grounded in a “double movement” in which the imperative to expand the market’s scale and scope generates a countermovement resisting such expansion, and ever rejecting self-regulating capitalism [

117]. Extrapolating this double movement in most post-colonial, post-Soviet as well as “post-european” (for example Greece and Cyprus) settings, we indeed observe a rapid expansion of the market’s scale and scope since the 90s. In parallel, the countermovement has also been growing, as several examples discussed in this paper indicate: Kumtor mine, the privatisation of commons and the assorted disconnect or resistance being the most emblematic amongst them.

Blyth, on the other hand, builds on Polanyi’s work, arguing that the double movement is a plausible heuristic, but not a robust theory of institutional change and, therefore, it must be reconceptualised [

117,

118]. The role of economic ideas, interests, and institutions should be remodelled on the basis of five hypotheses intended to capture the sequence of institutional change. The five hypotheses of Blyth [

118] can be summarised as follows:

- (i)

In periods of economic crisis, it is ideas and not institutions that are uncertainty-reducing mechanisms;

- (ii)

Once uncertainty is reduced, prevailing ideas make collective action possible;

- (iii)

In the struggle over changing existing institutions, ideas are weapons;

- (iv)

Once existing institutions have been delegitimised, new ideas function as institutional blueprints; and

- (v)

Following institutional crafting, ideas guarantee institutional stability.

In this frame we can plausibly assume that several existing institutions related to CPRs in transformative contexts were never truly delegitimised. In fact, pre-Soviet, pre-colonial or even pre-European structures have survived, indicating that institutional stability is strong and still supported by old, well-rooted and sometimes quite effective ideas. An example of this situation is the role of leadership in very diverse settings, associated with social status as a determinant for the success of new institutions like the resource users’ associations (e.g., [

50,

69,

76,

77]) and the stability of existing practices resisting change. Where the process of delegitimisation was concluded, however, as in pastoral practices in Kyrgyzstan, new ideas never managed to reduce uncertainty and allow collective action to a degree that would enable the formation of new and stable institutional structures [

119]. Instead, a different process is observed: the creation of new institutions based on past experiences as well as beliefs and perceptions of the current reality are followed by institutional change, again in response to unexpected developments (ibid).

In such transformative frame, Bogaert et al. [

120] note that each society consists of individuals, a number of whom are characterised as natural co-operators, understood as pro-social individuals whose behaviour is associated with a reversed utility maximisation decision-making process that strives to maximise joint outcomes, prioritises issues of equity and fair distribution, consistently seeks win-win situations or is even motivated by purely altruistic incentives. This pro-social behaviour is, however, typically discouraged by weak public institutions, hampering mutual confidence [

121]. In largely individualist societies, where social relations rely on weak ties and are mostly influenced by values related to power and self-interest, the belief that unknown others can be trusted is perhaps the best predictor of pro-social behaviour [

122]. Meanwhile, in largely collectivist societies, where social relations rely on strong group ties, trust in public institutions is crucial for promoting cooperation [

123]. Institutional trust, understood as citizen belief in the ability of public institutions to regulate interactions in a fair and effective way, can provide incentives to individuals to behave pro-socially [

122].

Viewing this collectivist-individualist bifurcation of human behaviour through Polanyi’s and Blyth’s lenses, we can assert that many countries considered “dysfunctional” today, are undergoing a process of transformation from largely collectivist societies, where ideas from natural co-operators were rather welcome, to individualist ones. We notice in parallel, that the occurring institutional change is not a process of smooth transition from a centralised or underdeveloped economy towards a free-market economy, as Western advisors and international organisations anticipated. Rather, it is an incremental process of trial and error with contradicting or yet to be seen results. In this frame, the power of ideas over institutions as the mechanisms that will reduce uncertainties deeply rooted in many transformative contexts has been underplayed at the policy making level.

5. Constructing an Understanding of the Role of Institutions in Transformations and Conflicts

The fact is that in many countries across the globe there are local, national and international institutions in place, together with bureaucracies and infrastructures that are meant to regulate the management of scarce natural resources in conflict-free environments, enabling economies to develop. Yet conflicts persist, questioning the success of any introduced reforms, especially when compared to pre-colonial, pre-socialist or even pre-European structures in a CPR management framing. So why are all these instruments not fulfilling their purpose? If these questions boil down to a matter of institutional design, then the new question to be answered is why institutional design and the subsequently introduced institutional changes and reforms are insufficient to resolve conflicts and—to paraphrase Commons [

25]—fail to address the social need of establishing harmony through institutional constraints? The work presented here constitutes a process of inquiry seeking to arrive at a plausible explanation for this problem. It must be noted that the bold attempt to connect Polanyi’s work on transformations, to institutional questions through Blyth, disregards some key issues in the literature. More specifically, Polanyi’s much less cited

Logic of Liberty [

115] sets the foundations for polycentricity and is directly aligned with the influential work by Vincent (and later Elinor) Ostrom [

116], establishing a clear link between institutional economics and Polanyi. Furthermore, the relation between polycentric governance, institutional change and conflict, especially when focusing on natural resources, has been recently recognized and is under empirical investigation (e.g., [

124,

125,

126]). Prominent institutional economists (e.g., [

127]) on the other hand have only sporadically touched the notion of “ideas” and transformations by Blyth, although as I argued in this paper, this could enhance our view on institutional change and the underlying reason of persisting or newly emerging conflicts.

In this frame, I argue that expectations regarding the behaviour of others [

58] and the interaction patterns [

57] created due to institutional reforms are problematic by nature, posing enormous obstacles to policy making and further bifurcating already divided views on controversial sectors of the economy, especially when related to resources that have been managed as commons for centuries.

Reflecting on the conceptualisation of institutions as discussed in the paper and relying on empirical evidence from diverse cases, we can safely come to the conclusion that in many transformative contexts there are neither effective institutions in place nor any chance to design and deliver new institutions that will fulfil their purpose. To a considerable extend, even the bottom-up arrangements that often replace existing structures are imposed in a centralized and context-insensitive manner. From both Bromley’s and Ostrom’s points of view, that is an endeavour doomed to fail. An important lesson is that even novel remedies, including self-organisation and governance (polycentric or not) as well as community-based management, focus on institutional performance rather than processes of institutional change. In our context we observe that processes of institutional change which took place in a top-down fashion, unleashed bottom-up processes too resulting, however, in phenomena such as opportunistic behaviour, corruption, bribery and clientism but largely failed to lead to self-organization, conflict resolution and collective action. Instead, it fueled suppressed conflicts or created new ones, raising the question what such conflicts might mean for institutional change processes. Institutions are mechanisms coordinating interactions between individuals and groups, structuring social rules and reducing uncertainty by defining and enforcing duties and rights with the ultimate purpose of avoiding conflicts. The empirical evidence from the management of CPRs in transformative contexts rather reveal mountains of contradictory assertions from contending interests precluding necessary deliberation and reason giving ([

128]), hindering further the development of effective institutions. In this frame, I further argue that deliberation and reason giving in settings loaded with contradictions and conflicts would provide fertile ground for new ideas to flourish. These ideas, in line with Blyth’s proposition, could pave the way for reducing uncertainties, enabling collective action, changing existing institutions and ensuring the institutional stability of the new ones.

Further reflecting on the literature discussed in this paper, we notice that although there is a growing demand for new transformations challenging the Western model of development, in practice the very same transformation processes that shaped Western societies from the 19th century onwards are taking place in the “dysfunctional” contexts of today. This is connected to a shift in the views and practices of international organisations since the early 1990s, recognising the importance of institutions as a response to the ongoing crises of the developing world, failing to understand however what exactly institutions are. Moreover, growing environmental problems and conflicts related to natural resources have also been associated with institutions in place or a lack thereof. However, lack of knowledge on how institutions are crafted or designed, how they change, and why they succeed or fail, has resulted in poor, results in many contexts where institutional change has been imposed. Yet the same recipe of transplanting exogenously designed institutions, even when a bottom-up approach is preferred rather than the top-down authoritarian models of the past, is seen again and again with limited results. In this setting, the possibility that crises might legitimise changes that would otherwise not be accepted becomes particularly relevant, in cases where social progress and democratisation processes are at stake.

Moreover, we notice that the existing literature focuses primarily on institutional change and reforms occurring within single transformative contexts (most notably post-colonial and, since the early 1990s, post-socialist), often dealing with a single resource and addressing only partially the dynamic interrelations between actors, their decisions and natural systems. Consequently, contemporary research has only produced fragmentary knowledge. Although it acknowledges the ground-breaking work of Elinor Ostrom and admits that economic orthodoxy has been unable to explain how and why institutions change, it has yet to sufficiently explore how such change is related to resource-related conflicts in contexts where imposed institutional changes rapidly transform the relationships between humans and nature. Most importantly, there are few studies that view institutions not either as part of the problem or part of the solution but rather as both solutions and problems for different actor groups, sectors, regions and so on.

Bridging this gap would require bringing together findings from different settings and propositions from different disciplines in a synthesising manner, so as to enable a holistic view and better understanding of the processes of institutional change. Only then, on-going transformations in natural resource management could be sufficiently understood, studied and even steered. This in turn, would allow policies with concrete targets to be introduced and implemented. This paper and the special issue as a whole contribute to this laborious effort and attempts to shed light on a number of so far underplayed issues that might explain the questionable transition path of nations with weak economies, loaded with conflicts, into sustainable, economically developed democratic states.