1. Introduction

Food security is a phenomenon with a double approach at the global level. The first one focuses on social aspects and is strongly interconnected to sustainable development, while the second approach analyzes the causes and effects at the national and international level and suggests measurement indicators. Specific initiatives to solve local problems generated by the food insecurity of various population categories are rising. Given the large development gap between rural and the urban areas in many countries, the topic of food security at the level of poor communities represents an issue worth researching.

Increasing interest in food security was led by factors such as population growth, changes in consumer habits, deficit of natural resources, and the impact of climate change [

1]. To address these global premises, the European Union (EU) became more concerned with ensuring sustainable growth in food production. Besides supply security, the EU has also engaged to ensure a healthy diet together with training programs regarding healthy eating habits and health-promoting foods. Balanced nutrition has become an expression pegged to the rising living standards of European citizens.

Unhealthy eating might have significant consequences such as obesity. In recent years, the increase in the EU’s overweight population has reached an alarming quota. On average, 17% of the adult population suffers from obesity and 52% of European adults are considered overweight [

2]. The main causes of this situation are unhealthy diets and inappropriate lifestyle, so the idea of some coordinated action in this matter arose.

In 2005 the European platform for action on diet, physical activity, and health was launched, with a view to establishing joint actions in the fight against obesity and promoting health in the context of European policies by integrating it into the framework of other policies (social, agricultural, consumer, etc.). It was followed by the Action Programme in the field of public health, with the aim of providing specific information and support to promote physical exercise, healthy eating habits, and balanced nutrition.

Thus, in recent years, the issue of food security became a major concern for the EU. In order to address this problem, it designed and implemented various programs and schemes at different levels, some of them being directed towards children enrolled in schools. Within EU member states, 12.2 million children from over 79,000 schools have benefitted from the distribution of fruit and vegetables and about 18 million children had access to the distribution of milk during the 2016–2017 school year [

3].

The EU legal framework regarding the consumption of food products in schools, called “The Programme for Schools,” streamlined and unified previous programs. The new scheme is focused on fresh products supplied from local and regional sources, a specific budget allocated for the two categories (fruits and milk), the possibility of transferring up to 20% of funds from one category to the other, and educational measures for both categories of food [

4]. The program is destined to form healthy dietary habits for children over the long term by encouraging the consumption of local products.

Such programs of designing sustainable institutional food systems in public schools have brought remarkable results all over the world, e.g., in Canada [

5], Italy, Brazil, Colombia, Japan [

6], and also in the United States, where the initiative started in the 1990s under the farm-to-school concept [

7]. Oostindjer et al. (2017) make a comprehensive cross-national review of school food programs and stress the need for a long-term approach, considering school meals an integrative platform for sustainable and healthy food behavior [

8].

Considering the abovementioned aspects, food security becomes an essential component for both nutrition and public health concerns at the EU level. While the production protocol, the geographical origin of food, and the impact of distribution are obvious elements, a proper policy should also include a sustainability component for assessing the environmental impact [

9].

Despite the efforts of the EU to reach economic convergence through its multiannual structural funding policy, regional disparities persist. This is valid not only between member states, but also at the intraregional level. In Romania, most people at risk of poverty live in rural areas. The differences that characterize the urban/rural divide in Romanian society show that while only 11% of people living in densely populated areas are at risk of poverty, 38% of those living in thinly populated areas face such a risk [

10]. However, rural poverty manifests itself in different ways, from the poverty of small villages and those with aging populations to deprived communities characterized by low skills, low employment, and inadequate housing.

Within the EU, Romania ranks fifth according to the agricultural arable area. Fiscal measures intended to reduce the burden for local food processors along with support for agricultural producers could improve Romania’s food security in the coming years. Technological upgrading in low-income rural areas of Romania can work well if coupled with market opportunities. An association of small farmers is bound to succeed if there is a guaranteed and stable demand from the institutional side (such as schools and hospitals) with prices kept stable and decent. This way, household food insecurity could be diminished for the most impoverished rural areas in Romania.

In Romania, the concept of food security, its characteristics, and its consequences from an economic perspective are insufficiently explored in the literature. This paper tries to fill this gap with a theoretical and applied study on food security for children in rural areas. This subject carries major importance for the sustainable development of the country, considering the large development gap between the urban the rural environment. The need to improve the poor living conditions in rural areas may start with efficient policies applied towards implementing basic healthy eating behavior for children. The novelty of this paper comes from the fact that there are no other applied papers focused strictly on investigating the matter of food security in detail and formulating managerial implications for policymakers.

The research presented in this paper is of a qualitative type and its goal is twofold: to investigate the manner in which food security is ensured for school children in rural areas, and to determine the opportunity of implementing sustainable programs by which a hot meal is served in schools. The specific objectives of the research focus on the opinions of teachers working in the rural area towards ensuring food security for pupils, the influence of nutrition on the educational process, the causes that contribute to food insecurity for children in rural areas, and the opinion of experts about the programs implemented to improve food security for children.

The implementation of the research was done by closely following the development of a project co-financed by the European Social Fund of the European Union, called “I learn, I play, I am happy at school.” The objective of the project is to reduce the number of students who drop out of school and to promote equal access to quality primary education.

The research is structured as follows: In the first section, the literature review highlights important propositions regarding food security, the next section describes the methodology used for the research, and the results of the research linked to the abovementioned project are presented in detail in the third section. These are followed by a discussion concerning the contribution of this paper to the literature and potential application of the results. The concluding section emphasizes the role several institutions might play in implementing such projects of ensuring food security and indicates future directions for research.

2. Literature Review

Food security as a concept emerged in the 1970s. The essential elements in the definition coined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) are food availability for rising consumption, avoidance of production fluctuations, and stability of prices [

11]. The same organization focused later on food access, considering the balance between supply and demand as being essential for food security [

12].

In 1996 the definition of food security was revised to include the significance of each of the so-called four pillars: food availability, access to food, use of food for a healthy life, and long-term stability of food production [

13]. These pillars are influenced by various factors at the global and national level, such as agricultural production, infrastructure, international policy, education, and gender issues [

14,

15,

16].

Moreover, food security is closely connected to sustainable development, implying a wide range of strategies from agriculture to food hygiene in cultural, environmental, geographic, and socio-economic contexts, which are extremely complex [

17,

18,

19]. As some authors point out, even if food insecurity manifests itself in individuals, households, and local communities, its causes may have wider origins, reflecting political and economic decisions as well as configurations of food systems. This is why the level of analysis and action needs to be larger [

20].

Empirical studies highlight different experiences regarding the achievement of food security in various countries and periods. In Europe, for example, total food supply is not the only factor to be considered, but also the purchasing power of individuals and the nutritional quality of foods [

21]. As such, half a million people in Europe do not have access to sufficient foodstuffs and around 20 million families cannot afford meals of a high quality on a regular basis [

22]. In the United Kingdom, starting with the Industrial Revolution, the country became more and more dependent on imports of food, and over time the government initiated several policies regarding food security. In the 21st century, theses policies need to take into consideration the emerging constraints of global food supplies, climate change, and access to various natural resources such as land, water, and fossil fuels [

23].

Food security might seem like a problem specific to developing countries, considering the fact that insufficient resources may determine difficulties and shortcomings related to possible food insecurity issues. Nevertheless, as researchers point out, some aspects of food security can be seen in developed countries as well as a consequence of different economic factors such as inaccessibility of prices, debt, financial obligations, eating habits, hectic lifestyles, and so on [

21]. For instance, studies have shown that for people in Ireland coming from low-income households and living on minimum wage, it is almost impossible to afford a healthy diet. The same is true for the United Kingdom, where people on welfare benefits or state pensions find it nearly impossible for their income to meet the basic needs of healthy living [

24]. Thus, the issue of food security is approached in economically developed countries also in connection to the human rights perspective, to ensure the right of an individual to food and health.

In the current period, there are two extreme aspects associated with bad nutrition: insufficient calorie or protein intake and undernutrition on the one hand, and overnutrition as a result of excess calorie intake (and the associated increased risk of many diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and some types of cancer) on the other [

25]. In this context, the focus on the food system needs to take into account, as does the recent nutrition transition whereby diets traditionally dominated by regional staples are widely replaced by highly processed products high in fats, salt, and sweeteners [

26]. The nutritional side is integral to the concept of food security and is achieved when secure access to food is coupled with a sanitary environment, adequate health services, and knowledgeable care to ensure a healthy life free from malnutrition for all household members [

27,

28].

Romanian food policy generally aims to provide the necessary quantity and quality of food for the entire population at affordable prices, thus linking availability of food with purchasing power [

29]. However, the governmental approach to policy in the food sector has not been unitary throughout the years. The absence of a long-term coherent development strategy in this field and the low efficiency of its agriculture have led to an overreliance on imports of processed food.

Recently, a number of legal acts with impact on food security were approved. After its accession to the European Union, Romania had to update specific legislation and create all the mechanisms for putting it in practice. EU legislation regards not only food security and safety, but also consumer rights and the agro-alimentary field. The legal community’s regulatory acts—regulations, directives, and decisions—were integrated into Romanian legislation with the implication of specialized institutions such as The National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority. For instance, only in 2007 (the accession year of Romania to the EU), a total of 86 regulations, 25 directives, and 198 decisions were integrated into the Romanian legal framework [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Moreover, the importance of food security has been recognized recently by including it as a top priority in the Agri-Food Strategy of Romania for 2016–2035 [

34].

In a recent paper, Alexandri and Luca (2016) assess Romania’s situation concerning food security at national level, including access to food and the nutritional status of the population [

35]. The proposed methodology is based on the four pillars of FAO’s food security concept. The analysis reveals several weaknesses in Romania’s case, such as unstable and insufficient food supply; difficult access due to low income, especially in rural areas; and deficient food consumption in quality terms, which generates nutritional risks.

The poor diet quality of a significant part of the Romanian population can be attributed to factors such as subsistence farming, weak purchasing power, and lack of proper infrastructure. The low yields, existence of vast uncultivated farmland, and constant increase in food prices lead to difficulty for some segments of the population to cover the daily necessary amount of food with the available income [

36]. In the case of the Roma minority living in Romanian rural households, there is an even larger dietary gap towards the lower limit of the nutritional standard, as documented in a 2018 study by Ciaian et al. [

37]. Economic, social, and institutional factors (low income, no social insurance, weak participation in the labor market, discrimination, traditions, etc.) are responsible for this.

The measurement of food security takes several indicators into account, such as the quantity, the quality, and the diversity of food [

38,

39]. Another relevant food security indicator is the share of food expenditure in the total consumption expenditure of the household. The higher the share, the more vulnerable the respective household is from a food security perspective. In Romania, this indicator registers at a high level, although it decreased from 52.2% in the year 2001 to 40% in 2014, leading to a slightly higher access for the population to procure food [

40].

Food availability and food affordability are not evenly spread across the regions of Romania. Comparing consumption needs with the food availability regardless the source of origin, the food requirements are met at national level, as previous research shows [

41,

42]. However, food availability differs between urban and rural areas. According to several researchers, the most widespread cause of household food insecurity is poverty [

43].

Household food insecurity has proven to be a powerful stressor with a direct impact on the emotional, social, behavioral, and intellectual development of children, including problem internalization (e.g., depression) and externalization (e.g., aggressive behavior) [

44,

45]. Thus, the government can take important steps by establishing sustainable policies that protect, promote, and support optimal feeding behavior of children [

46].

In order to encourage healthy and balanced nutrition for Romanian children, the government initiated a national program in 2002 called “Milk and Roll,” following European models of distributing food in schools. It entailed the free distribution of milk or dairy products (200 mL units) without the addition of powdered milk, and bakery products (80 g units) in kindergartens and schools. From 2009 onwards the program was joined by another one, whereby fruits were distributed to pupils for a maximum of 100 school days. This program also included visits to farms, gardening activities, and various educational measures.

In Romania, in addition to the abovementioned scheme, the government initiated a pilot program in 2015 to supply a hot meal for children in 50 selected educational units. For the respective schools, the new program replaces the old fruit and milk scheme. Envisaged are schools in remote and low-income areas. The new program has brought results from a social perspective: The rate of students dropping out of school dropped from 6.1% in the 2015–2016 school year to 4.3% in the 2016–2017 school year and to 1.3% in the 2017–2018 school year [

47]. It remains to be analyzed in what ways the program has contributed to the food security of children in rural areas.

At the same time, Romania is one of the major beneficiaries of European Union funding for the 2014–2020 programing period, with the aim of reducing disparities in economic and social development between member states. Therefore, various educational programs have been designed that involve investments in integrated measures that simultaneously target the school (children, teachers, infrastructure), the family, and the community to increase the quality of education.

The main investment program is the Human Capital Operational Program (POCU). By means of 156 projects funded under so-called “School for all” and “Motivated teachers in disadvantaged schools,” the program aims to reduce school dropout through various forms of social support, from hot meals and supplies to grants and scholarships for more than 95,000 pupils, as well as teachers from disadvantaged schools. One such example is the project “I learn, I play, I am happy at school,” which is applied in the schools of the villages belonging to Voila Commune in Brasov County. This educational program is a “school after school” type, including pupils from rural areas among whom the assurance of food security was investigated.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the research is to analyze the food security of children in rural areas through the lens of a project co-financed by the European Social Fund through the Human Capital Operational Program. The project, where 150 school children from rural areas are included as the target group, lasts for 36 months. It is called “I learn, I play, I am happy at school,” and is being implemented in the Voila Secondary School and its subordinate units from the villages belonging to Voila Commune in Brasov County (center region of Romania).

The overall objective of the project is to contribute to the reduction of school dropouts and to promote equal access to quality primary education. One of the main activities undertaken by this project is to provide daily hot meals to school children in the target group, having thus provided appropriate nutrition according to their stage of development. The project also seeks to educate children and their parents in the target area through specific information and awareness actions on the importance of developing responsible behavior in terms of food security.

Given that the theme of the research concerns sensitive issues involving level of education, family spending, and implicitly the welfare and quality of life of these children, qualitative marketing research was considered the best method of approach, as it provides the necessary tools to investigate the human experience and to understand it thoroughly [

48].

The selection of participants was based on the assumption that they are best placed to provide relevant information. Most of these people interact daily in the educational process with children enrolled in rural schools. They can appreciate how the educational path of children is influenced by the living environment, including aspects related to food. Moreover, the interviewees have gained an overall capacity to determine the impact and limits of the implementation of the program of feeding the pupils a hot meal in the schools from the target group.

Most of the individuals interviewed were teachers (nine kindergarten and primary school teachers) alongside experts such as a psychologist, a doctor, two nurses, a trainer, a school mediator, and a school manager. A panel of 16 people were interviewed. These experts provide health education, regular monitoring of children’s health, and psychological counselling focused on raising self-esteem. They organize thematic workshops in the field of hygiene and personal care, conduct at mealtimes, and food recommended for children.

In order to accomplish this study, the researchers used an ethnographic approach [

49] and spent several days in Voila Commune, which involved doing working visits; interacting with the locals and the children from the target group in various contexts; observing their behavior, eating habits, and the conditions they live in; and conversing with parents, teachers, and experts working with children. They explored the needs and problems of children in terms of food security, these issues being contextualized from a family, educational, social, financial, and institutional point of view.

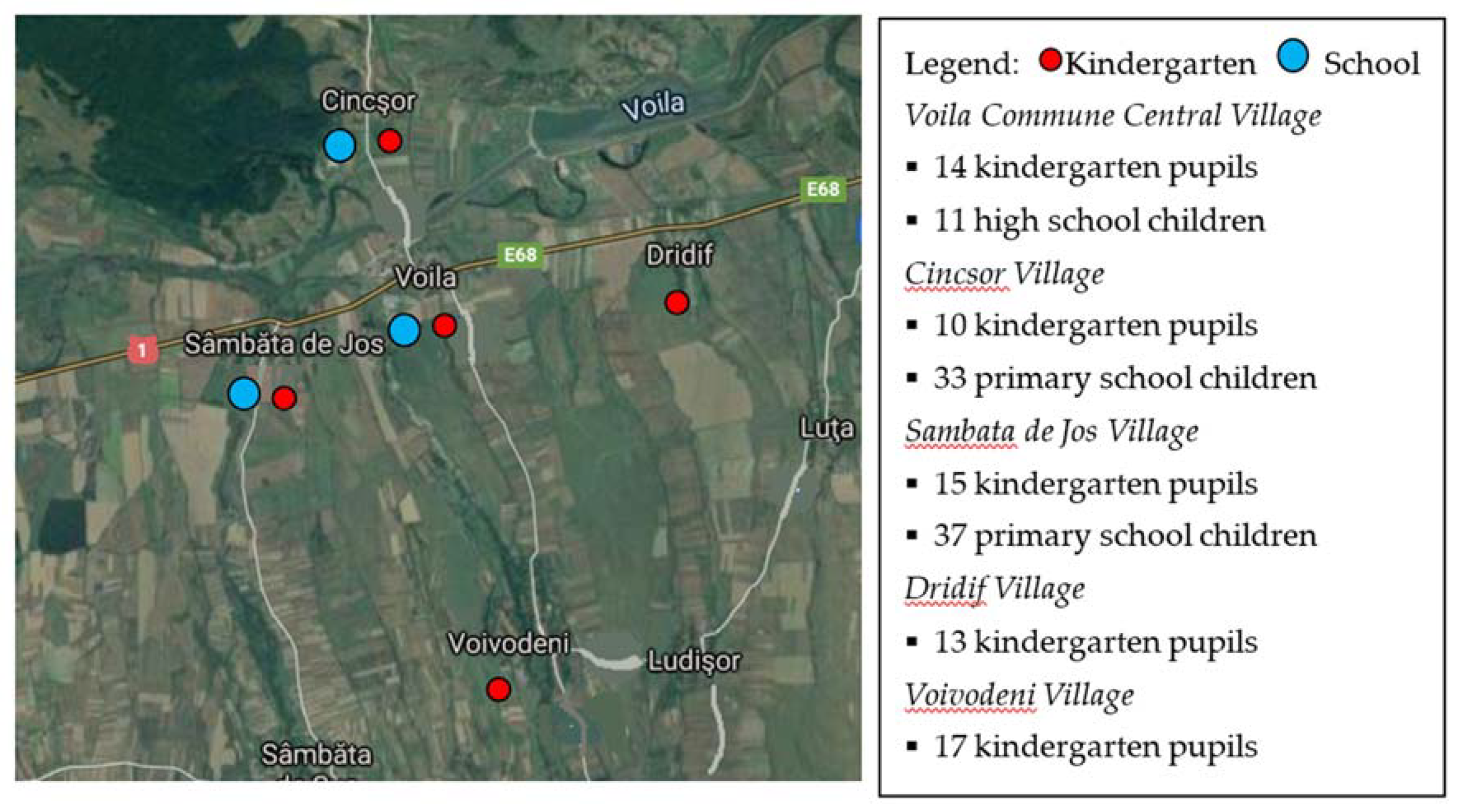

During this stage of the research, 150 children were observed as follows: Of the pupils enrolled in the kindergartens and schools included in the analyzed project, 69 were aged between 3 and 5 years and 81 were aged between 6 and 14 years. The location of the school units where the research took place is presented in

Figure 1.

Using an in-depth nondirective interview [

50], the authors sought detailed information on all aspects closely related to the investigated topic. The interviews were conducted face to face in November–December 2018, each lasting 60 to 90 min. Discussions continued until the researchers considered that all of the aspects had been considered and a thorough understanding of the topic was reached.

The interviews were conducted based on a tool of open questions that came out of the study aim and objectives. In the process of designing the interview guide, the stair-climbing technique [

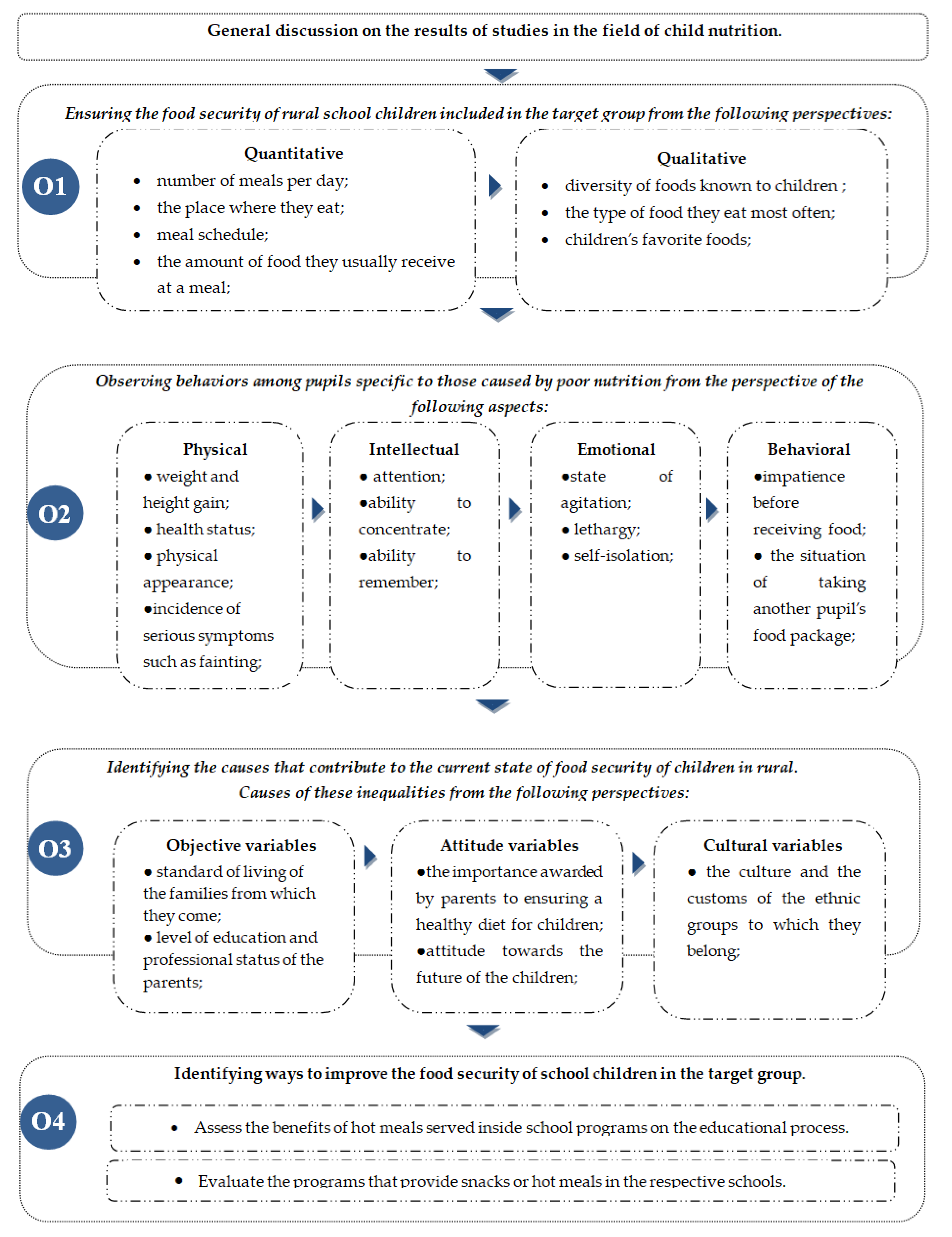

51] was used, and a logical chain of questions was designed to gradually emphasize the opinions of teachers and experts on aspects regarding food security of rural school children and to identify proposals to improve their situation. The flowchart of the interviews and the most important variables used are presented in

Figure 2.

From the complex answers of the interviewees, the authors extracted the relevant experiences, processes, relationships, and interactions related to the investigated topic.

4. Results

Taking into account the main research objective, namely to determine the opportunity to implement programs to ensure hot meals in schools in rural areas, and based on the analysis of the literature, four specific objectives were formulated to better target the approach. The results of the research are presented in the form of qualitative assessments for each of the four specific research objectives in order to obtain relevant and structured data.

- ➢

Objective 1–Identifying experts’ opinions on ensuring food security for school children in the rural area included in the target group.

In order to achieve the first objective, the interviews were oriented to address the two interrelated dimensions of analysis (quantitative and qualitative) that define the concept of food security. The quantitative aspect refers to ensuring the necessary amount of food to meet the physiological needs of school children in rural areas and the qualitative aspect refers to the food they consume from a nutritional point of view, so that the pupils’ health and school performance in rural areas are not affected or put at risk.

Conclusions inevitably developed around the idea that many of the children in the target group certainly do not have the benefit of minimum food comfort. The amount of food they receive in the family is either small or of poor quality. In each class, the “Milk and Roll” program is essential for nearly half of the children.

Most teachers participating in the research reported cases of pupils who came to school severely affected by the poor nutrition received at home. Some children even fainted at school, as they had not eaten anything during the whole weekend. All they ate during the day was the roll and milk provided during school hours.

With the start of the project in which children are offered a hot meal at school, teachers derived from the behavior of the children that they are very hungry. Pupils were interested in the day’s menu and asked multiple questions about its content. When serving a meal, some of them ate eagerly by holding on tightly to their casserole.

The parents of these children, due to lack of time, or, most often, out of convenience, do not cook. Some buy sweets that they offer to their children, a choice that is far from providing balanced nutrition. Teachers discussed situations of families who regularly urged children to eat sunflower or pumpkin seeds, including the shells, to fill their bellies.

There are children in the target group that tasted cooked food for the first time at school, starting with the abovementioned project. As they had not previously experienced prepared food with their family, some had a hard time getting used to cooked dishes. Some of the experts involved in the research declared that the children were not receiving enough food at home, neither in the necessary quantity nor quality. Unfortunately, these cases are not a few exceptions, but are typical for a part of the community that represented the target group in this research.

- ➢

Objective 2. Determining how diet affects the educational process and the development of children in the target group.

In the opinion of the interviewed experts, the development of skills is severely affected by the way children are fed. Poor nutrition influences them physically, intellectually, emotionally, and behaviorally. They often get toothaches, bellyaches, and headaches. The state of fainting is proof of the poor state of their health. The pupils’ performance is significantly affected by diet, according to most interviewees.

Psychologists participating in the research highlighted two aspects that work together in children’s well-being: eating and meal schedule. The regularity with which the children are fed a meal is as important as the food offered because it gives them psychological comfort. The better the schedule is, the better the child will feel, as adults at the schools can focus on development and cover higher motivational needs, having learned that the basic needs of children are fulfilled.

When asked to show how the diet affected the children in the target group, doctors stated that some of them were not well developed in terms of weight and height, and many suffer from anemia or indigestion. In the same context, the danger to which they are exposed due to poor hygiene and inadequate eating behavior is always present. Their taste is poorly developed and in the long run they will desire only certain foods they are accustomed to that are far from providing the necessary nutrients for healthy growth.

In consensus, the teachers interviewed believe that school performance is directly influenced by diet. Good nutrition ensures emotional stability and natural tranquility. As long as children are hungry, communication with them is inefficient. They are disobedient and restless, and cannot pay attention. Hunger even generates violence, but children calm down after eating.

- ➢

Objective 3. Identifying the factors that contribute to the current status of food security of children in rural areas.

In the process of identifying the factors that contribute to food security of children in rural areas, experts involved in the research focused their explanations on real-life aspects. Inequality among children is a recognized fact when it comes to access to food, explained by differences in family budgets. But when delving deeper into the causes that lead to poor food security for children, interviewees concluded that there is a simplistic and incomplete explanation.

Objective variables alone such as living conditions, education level, or professional status of parents are not enough. Lack of food security for children is better explained by attitudinal variables such as the importance parents allocate to childcare and to the future development of children.

Many pupils arrive at school without eating breakfast, and a sandwich for lunch is often missing. Family food is based on cold, inexpensive, purchased food. If these habits do not change, they will continue in the families the children establish, transferring them from one generation to the next.

From the discussions on nutrition with parents in the target group, it came out that they did not realize they were under-nourishing their children or feeding them improperly. In many cases they argued that they had nothing to offer at home. The reasons why children did not bring a packed snack to school were sometimes simply that their mothers did not care, did not wake up in the morning, or did not have the means, especially in the case of families with a high number of children. Thus, children looked forward to receiving lunch at school. This worrying fact is confirmed by the teachers participating in the research.

It can be concluded that access to food is characterized by a strong social and cultural selection. Explaining the lack of food security for children in the target group through economic inequalities is not enough. It is necessary to add the culture of the ethnic groups of families and parents’ attitudes towards children’s nutrition.

- ➢

Objective 4. Identifying ways to improve food security for school children in the target group.

Reducing the risks faced by children in the target group requires urgent action from all responsible institutions at the national level so that this social category has access to sufficient, quality-checked food. Experts participating in the research believe that persistent education and timely programs can contribute to developing a culture of consumption among the appropriate target group. This culture could lead in turn to overthrowing current trends that impose negative implications on inadequately fed rural children.

When considering the programs designed to improve food security for children, most interviewees agreed on the minimum support for pupils, while expressing disappointment about the quality of products offered inside the “Milk and Roll” program. The products are transported weekly to a lengthy distance. Thus, their characteristics decrease severely until consumption. Some of the teachers remembered that at the start of the program, products were delivered by a local vendor and reached the children in a fresh state.

Regarding providing hot meals as part of the project, all participants made positive assessments. They believe that it contributes to reducing inequality among children in terms of access to food, offering them a chance to develop normally and to focus on education. Children become more attentive after eating and more eager to learn. Eating a hot meal is a change for the better, as it comprises the necessary nutrients adapted to the age of the children. From the experience of the experts interviewed, food underpins behavior and mental performance

At the same time, experts agreed that a sparse project, implemented temporarily, cannot generate a big impact. Success is inconceivable without persistence and long-term involvement of all factors, including parents. If at school children learn to eat products that provide them with a minimum of security, in time, they may force parents to change their own habits. The implementation of sustainable programs in which hot meals are provided to children in all rural schools is, according to research participants, a solution to combat the phenomenon of food insecurity in its complexity.

Only by becoming institutionalized, with well-defined objectives and the allocation of human, financial, and logistical resources, can the results of such projects bring long-term success to forming positive behavior towards sustainable food security for children. Connecting the experts and stakeholders in the field is essential for the success of these projects.

5. Discussion

The complex phenomenon of food security is increasingly analyzed in the literature, along with growing concerns worldwide regarding the eradication of hunger, and, at the EU level, regarding the assurance of healthy and balanced nutrition in a sustainable way.

In Romania, aside from food safety, food security per se is still an insufficiently explored field from an economic perspective. Most contributions belong to connected areas (commodity science, food chemistry, agriculture) or focus on fighting poverty when the theme of rural development is approached. This paper contributes to the literature in the field with a theoretical and applied research on food security of children in rural areas, a subject of major importance for Romania’s long-term development. The study has a novel character, as no similar academic research has been conducted in Romania with the exception of ministerial assessments regarding the impact of programs for distributing food in schools.

According to the opinion of experts interviewed during the research, access to food for school children in the target group is deficient and has negative consequences. The increasing food insecurity of children in rural areas is generated by the emergence of multiple social and economic factors (purchasing power, structure of the family, etc.) and cultural factors (traditions, habits of families, etc.).

The results of the research form important recommendations for public bodies at the national and local level, such as the Ministry of Education and Research, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and City Halls. These can support the sustainable improvement of food security in rural areas. The research undertaken highlights the urgent need to implement a national program of minimum support by offering hot meals in schools for rural communities affected by persistent poverty, which will have positive and sustainable effects on the balanced development of children.

6. Conclusions

Romania is committed to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals set out in the United Nations 2030 Agenda, which promotes actions aimed at ensuring the balance between the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social, and environmental. Romania’s policy stipulates that programs that meet the objectives of the 2030 Agenda should be implemented by local institutions and included in regional development strategies. Thus, by implementing local and regional educational programs for children, intervention activities can be provided to contribute to achieving goal number 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all, and goal number 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture by ensuring access for all children, especially the poor and vulnerable, to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food throughout the year.

The development of the program of providing food support for school children is part of the actions of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research under an integrated intervention mechanism to reduce absenteeism, risk of exclusion, and school dropout. Compliance with the principles of healthy eating and teaching children about dietary habits is problematic with school children from geographically, economically, or socially disadvantaged backgrounds. Such actions are meant to contribute to the achievement of the major objective of the educational policy and to ensure equitable and non-discriminatory access to quality education for all children and young people in Romania.

However, particular importance should be awarded to assessing the results obtained from the implementation of educational programs and analyzing how each action will be completed, as well as the effectiveness of the measures taken. In the absence of an overview, educational strategies can be designed to meet certain objectives, but without correlating them with the specific needs of the target groups, they will prove inefficient in the long run. To respond more effectively to the challenges of the current context, the authors recommend that Romanian policymakers implement complementary programs to the compulsory school curriculum, such as “school after school” schemes, especially in disadvantaged rural areas. These schemes could offer learning opportunities through non-formal educational activities aimed at the personal development of children regarding lifestyle, nutrition, dietary habits, personal security and safety, etc.

The main limit of the present research is generated by the impossibility of extending the obtained results, a limit imposed first of all by the specific character of the research method used. In addition, only the views of experts involved in the education of children in rural areas in the villages of Brasov County were identified in this research. Despite these limits, the authors consider that the paper brings valuable empirical contributions to studying the issue of food security. Starting with these considerations, future research could be extended in order to assess the views of experts working in other rural areas as well as other interested parties, such as parents, nutritionists, teachers, policymakers, etc. The researchers aimed to measure the influence of various economic, social, and family factors on the inequality of access to food through quantitative marketing research methods that allow for the extension of the results.