Abstract

Road safety is an ongoing challenge to sustainable mobility and transportation. The target set by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) suggests reframing the issue with a broader outlook and pragmatic system. Unlike previous road safety strategies and models that favour engineering solutions and legal instruments, there is an increasing need to consider local context and complexities. While such principles have been increasingly featured in higher-level policy frameworks in national or state-level strategies (e.g., Safe System or Vision Zero approach), an effort to translate them into implementable actions for local development areas is absent. To address this gap, this study aims to develop a conceptual framework to examine the nature and extent to which statewide principles are translated into local government policies. We outline a 4C Framework (consisting of clarity, capability, changing context, and community engagement) to evaluate local policy integration in Perth, Western Australia. A five-point indicative scale is applied to evaluate the selected policy instruments against this framework. The results show that only a little over a quarter (27%) demonstrated a highly satisfactory performance in capturing higher-level policy objectives. The low-scoring councils failed to demonstrate the ability to consider future changes and inclusive road design. Councils along the periphery having new residential development showed comparatively greater success in translating overarching strategies. Regional cooperation has been very effective in enabling local agencies to adopt a more sustainable pathway to road safety measures. The criteria proposed within the framework will play a pivotal role in effective policy integration and to achieve more context-sensitive outcomes that are beyond the scope of modern road safety strategies.

1. Background

Road-traffic-related deaths and safety issues are ongoing concerns in metropolitan transport planning. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG Goal 11.2) specifically recognise safer roads as one of the key elements of sustainable mobility and transportation [1]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated around 1.35 million annual fatalities across the globe [2]. The SDGs’ target of a 50% reduction in the death toll through the United Nations’ Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011–2020) still remains a significant but distant milestone, despite the fact that it is already 2020 [3,4].

Road safety research has relied significantly on knowledge from practice for a critical insight to the theories, models, and strategies for risk reduction. Over the decades, the overall approach to road safety strategies has been a simplistic and reductionist one that followed an objective-oriented assessment. A multi-causal perspective, taking into consideration a series of factors contributing to the occurrence of road crashes, is rarely addressed. Wegman [3] pointed to the overwhelming emphasis placed on accident data (also referred to as a data-driven approach) and engineering solutions. Hagenzieker, Commandeur [5] defined this paradigm as being guided by three E’s: Engineering, Education, and Enforcement. Such a paradigm is based on a common misperception about road safety that associates it exclusively with speeding and risk-taking behaviour on the roads. While road crashes are subjected to legal investigation to determine enforcement measures and penalise behavioural misconduct, they by no means explain the full extent of the problem [6].

During the past few decades, there has been a policy shift towards promoting a system approach to address road safety measures by taking into account human factors, environment, and causative agents as defined by the Haddon matrix [7,8]. In the early 1990s, the Dutch ‘Safe System’ approach pioneered such paradigm shifts where both road designers and road users have shared roles to play [9]. While the earlier road safety management approaches were biased towards users’ performance on road, focusing on who or what caused the crash, the Safe System approach looks beyond that and treats crashes as a system failure. It emphasises that “the current road system is inherently unsafe and that road users are frequently placed in circumstances where errors are to be expected” [6]. Between 1992 and 2002, Sweden and Australia adopted a system-wide approach with an increasing reliance on behavioural and psychological theories of road safety management. However, there is a lack of evidence on transforming such strategies into implementable actions.

The Safe System approach is typically defined by its four pillars, including safer roads, safer vehicles, safer speeds, and safer road users. The ‘safe’ road users approach adopts a behavioural perspective focusing on the human ability to use the road in sustainable ways. There are, however, many ramifications with extant legislative and regulatory measures to control human errors in the system. In 2011, the United Nations put road safety on the global agenda, calling for an international coordination among countries to promote sustainable mobility through adopting the Safe System approach [10]. Meanwhile, in 1997, Sweden introduced a ‘Vision Zero’ approach that elevated the responsibility of road designers to consider a long-term vision with enhanced “philosophical and ethical value of human life” [9]. Several experts claim, however, that despite an increasing concern with human behaviour and psychological factors, recent approaches in many developed countries continue to remain focused on infrastructure-based measures, referring to national implementation strategies [10,11,12,13,14].

2. Australian Experience

Australian public policy on road safety response in the early stage of adoption of the Safe System approach mirrored the global trend, with a restricted and limited outlook targeting the behavioural change of drivers through instrumental measures. Even the National Road Safety Strategy (2001–2010) failed to offer a sustainable framework of road safety to deal with broader societal issues like perceptions of safety, comfort of driving, shared responsibility, and the psychological ramifications of road infrastructure [15]. The outcome was not remarkable, with only 3.3% reduction in annual road fatalities noted after the adoption of this approach, a far cry from a 30% reduction in road fatalities set by the current National Road Safety Strategy (2011–2020) by 2020. Inspired by Swedish Vision Zero and Dutch ‘sustainable safety approach’, the Australian Safe System approach upholds four key principles: recognition of human errors; absorption of kinetic energy by improved vehicles; shared responsibility to prevent crashes; and strengthened entire road systems to protect road users [16]. Referring to the insignificant success of the Australian approach, Hughes, Anund [17] argued that the core idea of the systems approach and its underlying elements is yet to be adapted to the local context. Picton and Bueren [18] further added that “the vision of zero is admirable, moral and endorsed by the community”—however, it is unclear how this can be achieved [18].

Hughes, Anund [17] maintained that, because much of the discussion around improving road safety strategies revolves around the overarching goals of higher-level policy making, ambiguity and confusion remain unresolved in translating them into implementable actions. Although Hagenzieker, Commandeur [5] claimed road safety research “is now moving into an increasingly scientific and cross-disciplinary phase”, many critics point to the need for wider socio-cultural shifts and community engagement in designing effective road safety measures [3,15,19]. Many road safety scholars maintained that implementation strategies would be critical to success, especially in the face of the changing socioeconomic context and development trends in metropolitan areas [17,20]. Wegman [3] further claimed that while “Safe System principles are rather universal … local conditions and circumstances will dictate how these principles can be translated into local action”. However, there is a dearth of research on implementation frameworks to evaluate these emerging principles associated with the sustainability turn in road safety strategies [15]. Moreover, despite the uncertain territory of future road safety, current efforts remain directed towards a wider policy level, paying little attention to how local context and conditions should inform policy implementation and define community engagement protocol. As a result, the vast majority of road safety strategic actions still rely on road engineering and driver education and enforcement. This is an area of increasing concern for many local government areas in Australian cities experiencing significant changes in their physical form (i.e., built environment) and witnessing socioeconomic transformations.

To address this gap in road safety research and policy integration in the local context, this study aims to develop a conceptual framework to examine the nature and extent to which statewide principles and policies are translated into local government jurisdictions of the Perth Metropolitan Area (PMR) in Western Australia (WA). In this regard, we focused on recent transformational actions of road safety principles by assessing the extent of policy adoption and the incorporation of community sensitivities. This was done by evaluating local policies and strategic documents of local governments. Based on an in-depth policy review of 30 local governments in the PMR, the paper seeks to highlight the status of road safety governance and the pathway to a more sustainable mobility framework.

3. A Conceptual Framework to Examine Local Policy Integration

This section sets out to critically discuss the theoretical underpinnings of higher-level road safety policies. The discussions will aid in outlining a comprehensive and pragmatic framework enabling policy evaluations on road safety measures. Evaluation of planning policies and strategic documents provides critical information on their operational efficiency and quality of performance in relation to the broader goals and targets [21]. The method further enables us to comprehend philosophical shifts in the development of road safety strategies and policy frameworks, moving from a quantitative outlook to a more inclusive and contextualised approach [22]. Michie, Van Stralen [23] questioned how well policy intervention frameworks of behaviour change improve the design and implementation of evidence-based practice. Their systematic literature review scrutinised 19 such frameworks for comprehensiveness, coherence, and links to an overarching model of behaviour and found that only a few frameworks met the criteria of coherence or linkage to a model of behaviour. With reference to interventions for behavioural change, Fylan [24] pointed to two main challenges: a lack of details of interventions provided and an absence of shared language to describe the interventions, making it difficult to compare the effectiveness of different models. Meanwhile, Greene [25] suggested the application of a combination of four spectrums in evaluating outcomes: interpretivism that recognises localisation of broader goals and understanding diversity; post-positivism that promotes efficiency and effectiveness in the implementation process; pragmatism that considers uncertainty, practicality, social, and cultural change; and, finally, normative science that promotes stakeholder participation in the design process.

This philosophical approach informs the formulation of the following four key research questions for this study that seek to assess the extent of the uptake of critical aspects of the state-level road safety vision at the local government level.

- Clarity of policy alignment—How clearly is the statewide road safety vision translated into local context?

- Capability considerations—How effectively are multifaceted risks resulting from the introduction of shared road users and competing travel demands accounted for?

- Changing contexts—To what extent do local policies and strategies consider uncertainty of the future and recognise land-use changes over time?

- Community engagement—To what extent are local stakeholders engaged in designing road safety measures?

3.1. Clarity of Policy Alignment with State-Level Thinking

Road safety research and practice underwent significant transformation in terms of policy direction since an organised approach started before the 1950s. The initial approach in road safety strategies relied heavily upon engineering solutions. The Risk Homeostasis Theory (1982) [26] suggested the inclusion of precautionary safety measures for vehicles and roads to reduce the risks [27]. This theory was criticised for promoting a sense of safety among drivers that, in turn, led to exposure to collision on the roads [19,28]. This prompted consideration of the entire road system, leading to a new paradigm of the road safety regime that looked into critical synergies between physical infrastructure and users’ risk perceptions and behaviour. The behavioural thinking concept attracted several multi-disciplinary fields of knowledge, like health, sociology, and psychology, to contribute to road safety research that took into account human factors and local texture [19]. A more recent shift to ‘sustainable safety’ by the Dutch and the Swedish ‘Vision Zero’ promoted strong ethical values in human life and considered sustainable utilisation of road infrastructure and users. The emerging philosophies enabled the shared responsibilities of motorised and non-motorised users and recognised transformation in the built environment. Several models and operational frameworks have evolved over time, which have incrementally added physical and human factors, such as Haddon’s Matrix [29], on sequencing crash phases; Risk Homeostasis Theory [26], on reducing drivers’ exposure to crashes by adding physical safety measures; Health Beliefs Model [30] that promotes the individual’s perceived knowledge of health benefits and its effect on behaviour; Theory of Planned Behaviour [31], to explain one’s perceived understanding of hazard and socio-psychological factors determining safety behaviour; and Gibbons and Gerrard [32]’s theory of the willingness model, which explains factors affecting safe driving behaviour among young and older age groups [33]. However, Hughes, Anund [34] argued that a comprehensive list of policy tools grounded on emerging theories and practices to guide local road safety management is yet to be developed. Hughes, Anund [17] comprehensive framework, consisting of seven components of road safety management based on system theory and principles, attempted to bridge the limitations of previous models but lacked empirical evidence and guidance for local applications with complex and emerging land use and transportation needs.

A comprehensive translation of statewide road safety at the local government level requires the formulation of implementable actions, context-specific targets, and broad-range projects addressing road safety components, including projects related to research, education, and regulation under a clear funding structure. Hughes, Anund [17] emphasised that specific policy tools, including micro-level strategies and interventions, are required in the goal reduction process. They stated that the guiding principles highlighted by the policies and strategic documents must demonstrate “moral value” leading to the practice (p. 37). It is contended thus that the outcomes of the emerging philosophies enshrined in the state-level policies should be demonstrated in their conceptualisation and translation in a local context to inform road safety practice. This should be observable as the policies move beyond adopting a data-driven approach towards a “context-sensitive mode of planning” [35] and become focused on users’ attitudes towards infrastructure, interventions, and technology [36].

3.2. Capability Considerations of Various Users and Nonlinear Risk Topography

A disaggregated view of the road safety paradigm suggests differentiation and clustering of issues in terms of understanding the risks and behaviours of various groups of users, such as different age groups, parents and children, local residents, etc. [8,37]. May et al. (2008) suggested that a segmentation strategy of road users and an understanding of their competing travel and safety demands are critical to sustainable transport system design. Such a strategy encompasses demographic or socioeconomic groups (e.g., groups based on age, gender, and length of stay in the area) as well as user types (e.g., pedestrians, cyclists, or drivers). A segmentation approach enables targeted interventions in place of blanket solutions that do not consider context and consumer demands.

A mix of land use and shared road users introduces further complexity in road safety management in local government areas. Mixed-use development generates a variety of road users, including pedestrians, cyclists, motorists, and school-going children, within a non-commuting context. Road safety measures should ensure a healthy and equal road-sharing environment. While, as Christmas, Helman [38] maintained, “infrastructure has a role to play in improving the culture of road sharing”, it is equally important to explore “the degree of safety they [users] are perceived to offer both to themselves and to other road users” [39]. Road safety strategies often do not include such an important factor, which is particularly critical for local government road safety measures.

Road safety research is often carried out in generalised terms rather than being focused on geographic, cultural, and social contexts [37]. Increasingly, however, cognitive and emotional perceptions of risk are recognised by the road safety researchers and practitioners. Elvik [40], for example, referred to the theory of planned behaviour as outlined by Ajzen [31] to establish the connection between sociocultural aspects and attitudes towards road safety issues. Elvik [40] emphasised that social norms, culture, interpersonal belief, and subjective rationality define the social context that influences attitudes and motivations towards safety issues such as those caused by speeding and drink-driving.

3.3. Changing Contexts Reflecting Future Trends and Uncertainty

The future is unpredictable, uncertain, and becoming more complex. Road safety measures developed based on historical data and stable conditions are unlikely to solve these growing complexities [41]. Therefore, a robust and comprehensive framework that can adjust with changing circumstances is critical [17]. Road safety is likely to be impacted by the changes in the context derived from demographic change, socioeconomic transformation, and technological innovation [17]. Several studies predicted changes in safety perceptions over the coming decades with the advent of new technologies and climate change, such as technological advancements in information and communication technology (ICT), automated vehicles (AVs), and measures to reduce CO2 emissions and mitigate other climate change impacts that could enhance vulnerability in road use [42,43]. Introduction of the Autonomous Emergency Braking (AEB) system in vehicles is expected to reduce driving errors significantly. As a result, traditional road safety measures will need to be adjusted with technological innovations [44]. Soteropoulos, Berger [45] further suggested that the introduction of AVs will “have impacts on accessibility and transport demand … on travel behaviour, such as the type of activities, number of journeys, or the choice of transport mode”. A pragmatic road safety framework should consider uncertainty and changes associated with future scenarios [46,47]. Such ramifications can be effective in preparing for major disruptions, e.g., those brought on by technological breakthroughs and lifestyle changes, and, more recently, pandemics.

The rise of the shared riding business model (e.g., Uber, Didi, and Ola) will contribute to changing travel behaviour patterns in the cities, which will definitely affect the nature of safety on roads [48]. Travel patterns and behaviours are also influenced by the changing land-use patterns. An increase in mixed-use development encourages a greater mix of various road users. With a strong infill-biased urban development strategy and the adoption of liveable neighbourhood design principles, local governments are embracing accelerated growth in Australian suburbs. This is leading to complex road safety issues and challenges to the overarching mitigated approach. Land-use-specific and dynamic design principles considering future growth trends are an integral part of the comprehensive planning.

There is also an increasing realisation that the road user’s preference and motivation is not static but rather often influenced by lifestyle and technological disruptions, such as smart vehicles [45,49]. New market demands might significantly dictate the transport preferences (e.g., active transport) in the road safety perception regime [15].

3.4. Community Engagement and Inclusivity in Road Safety Design and Management

Community engagement is seen as a prerequisite of sustainable development [50]. Exploring community perceptions, needs, and aspirations is seen as the first step towards defining appropriate and acceptable planning outcomes. While there is an increasing trend of promoting community engagement by the state agencies in designing road safety strategies, detailed policy directions are often lacking.

Road safety strategies have traditionally focused on incorporating legal mechanisms to implement actions and penalties. The new strategies require the adoption of a more bottom-up approach to shape community behaviour. According to Picton and Bueren [18], “A little over third of the community have no awareness or knowledge of the concept of a Safe System”. As local government agencies prioritise community awareness and participatory planning accompanied by clear budgetary allocations, road safety design professionals can take this opportunity for meaningful outcomes. Pursuing public participation in road safety research and design serves to inform, consult, involve, and collaborate with the community or road users to understand their behavioural reasoning and design preferences [51].

Michie, Van Stralen [23] suggested a three-dimensional system (COM-B system) to enhance community engagement and behavioural change, including: capability, motivation, and opportunity. Capability and motivation refer to an individual’s psychological or emotional judgement and willingness to be involved in decision-making. It also leads to one’s planned behaviour on roads and engagement in community-wide measures [31]. Opportunity, on the other hand, emphasises interventions and factors promoted by external sources such as the local government agencies. It is important to investigate the extent to which local government agencies undertake the promotion of community engagement, i.e., whether they merely offer a lower degree of participation (informing) or higher-level participation in the decision-making processes. Effective community engagement also facilitates the monitoring and collection of feedback on the impacts of policy implementation, which enables relevant agencies to initiate adaptive measures to adjust with changing contexts [52].

4. Study Area Context

The study focuses on local governments in the PMR of WA to examine local policy integration. Road safety has remained one of the alarming concerns in relation to urban and regional roads in WA. The latest state strategy, Towards Zero–Road Safety Strategy 2008–2020, was endorsed by the Western Australian Local Government Association (WALGA) in 2008. The strategic vision adopted the principles of the Safe System approach. WALGA set the Towards Zero vision to “eliminate death and serious injury within the road network by creating a safe system that accommodates human error and the vulnerability of the human body” [53]. To capture the major shift in road safety management in local government, WALGA’s Local Government Safe System Project (LGSSP) (2009) stepped beyond the conventional approach and suggested the shared responsibility of all government and non-government actors in translating the broader principles of the Safe System approach to the local community level. The significant role of local government in promoting “moral and ethical standpoints” to achieve positive outcomes on roads was widely accepted [53]. The strategy aimed at a 40% reduction in the road fatalities by 2020, taking the number of occurrences during 2005–2007 as the baseline [54]. The fatality rate was recorded at 6.3 per 100,000 persons in 2019, which was higher than the target set by the Towards Zero vision, as well as the national average of 4.7 per 100,000 persons [55]. The recent crash data released by the Road Safety Commission clearly showed a nonlinear risk topography stemming from various factors involved in crashes on WA roads [56]. Around 45% of metropolitan crashes in 2019 occurred by colliding with nearby walls and trees. The number of fatalities in the last year involved various vulnerable road users: 20% were motorcyclists and 6% pedestrians. The crash data reveals that 58% of all crashes on WA roads in 2019 were related to drivers’ behavioural factors, including speeding, drink-driving, fatigue, and inattention. The male population was over-represented (74%) in crash incidences [56]. This has further necessitated translating the broader vision into implementable actions for the local context. In response, the RoadWise programme of WALGA recently offered support to local government in implementing the Towards Zero vision, particularly in developing policies and campaigns [54].

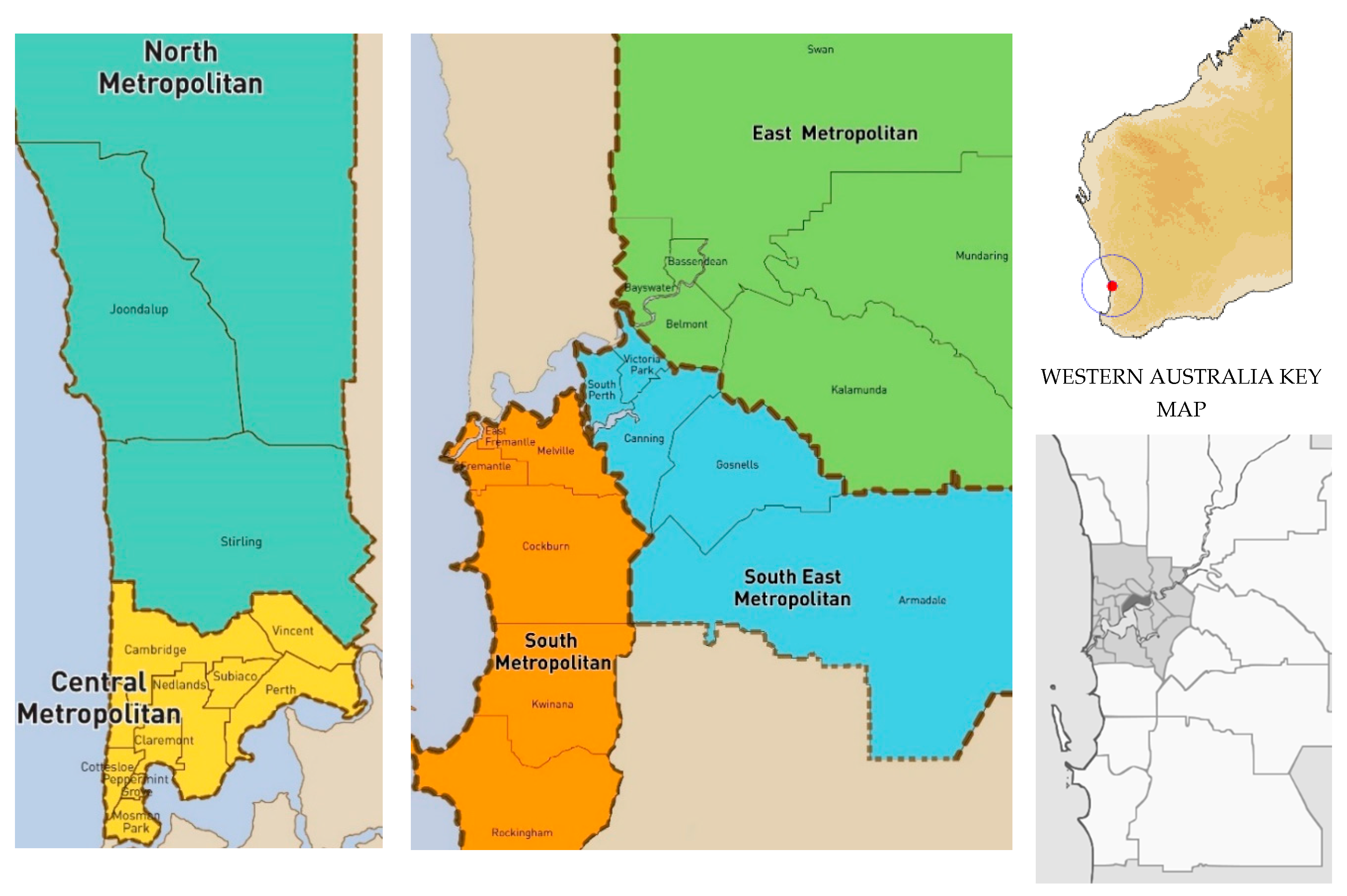

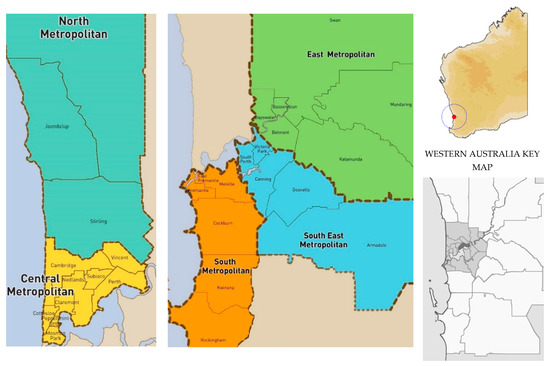

The PMR consists of 30 local government areas that are grouped into five metro regions by the WA Local Government Association (WALGA) (Figure 1). Local government roads are a critical part of the road safety management, as 84% of the Australian road network lies within local government jurisdiction, where almost half of all road casualties occur [56]. In WA, 88% of all roads are managed by local governments, where 61% of all serious crashes occur. Although most of the local governments in WA have demonstrated a positive attitude towards adopting Safe System principles, several limitations remain, including a lack of clarity and guiding principles in policy integration, competing priorities, and limited funding and other resources. In this regard, WALGA [53] called for more evidence-based road safety strategies to implement on local roads.

Figure 1.

Local government councils in the Perth Metropolitan region (PMR) [57,58].

5. Methodology

In this study, we analysed relevant policy documents of 30 local governments in the PMR to examine the adoption of the state government’s road safety vision. The policy documents were collected from the respective jurisdictions’ official websites. The policy assessment method was adopted from previous planning studies that demonstrated the benefits of policy document analysis to understand the trend of local planning practice [59]. Major planning and community planning documents and other relevant policy documents addressing local transport development were reviewed and analysed. A comprehensive set of evaluation criteria based upon the conceptual framework was used to examine the translation of statewide road safety strategies and the extent of their adoption by local governments. The criteria were adopted and modified from Hughes, Anund [17] 7P Systems Framework criteria, which were originally applied in evaluating state-level road safety strategies in Australia and New Zealand. Table 1 lists and summarises the types of policy documents reviewed in this study.

Table 1.

Types of policy documents selected for policy analysis.

This paper adopted a document analysis approach, subjecting a range of local government policy documents to a multi-criteria evaluation. It sought to assess the effectiveness of the policies in reflecting the higher-level principles enshrined at the state level. The relative effectiveness of the policies was measured along the four critical dimensions identified in the literature review presented in the earlier sections. The resulting ‘4C Framework’ for policy evaluation measured the following principles: Clarity of policy alignment; Capability considerations of various users; Changing contexts; and Community engagement. Applying the 4C Framework, we thus set out to examine local government policies in terms of their clarity regarding safety, their capability of responding to the competing demands of various road users, their level of consideration of future context, and, finally, their willingness to engage the community in the process.

A five-point indicative scale was applied to evaluate the selected policy instruments against each criterion. While no defined hierarchy was developed to assess local road safety strategies, an indicative scale and narratives commonly available in existing literature and public policy documents were used. The basic scoring scale was thus developed and adapted according to the concepts and indicative search keywords/terms (Table 2). A list of keywords used in this analysis to determine the councils’ performances across 12 criteria of the 4C Framework is presented in Table 3. The evaluation was based primarily on a keyword search for text related to the four criteria in target policy documents and the nature of their treatment or incorporation in those policies.

Table 2.

Measuring the incorporation of state-level policy directions.

Table 3.

4C Framework to examine the adoption of the statewide road safety vision into the local context.

An aggregated score of each council calculated across the 4C Framework was further grouped into three policy integration categories: below margin, evolving, and competent. A score of 1 or 2 was clearly suggestive of an absence of effective incorporation of state-level policy directions. On the scale, a score of 3 represented a minimally adequate level of incorporation. Therefore, a score from 1 to 3 demonstrated a position below the margin. A score from 3 to 4 represented an evolving context where councils had streamlined relevant policies/strategies for implementation but lacked implementable policy tools; above 4 was an indicator of higher competency, showing commendable performance across all 12 criteria. The description of criteria and an explanation of the scoring methods are found in Table 3.

6. Results

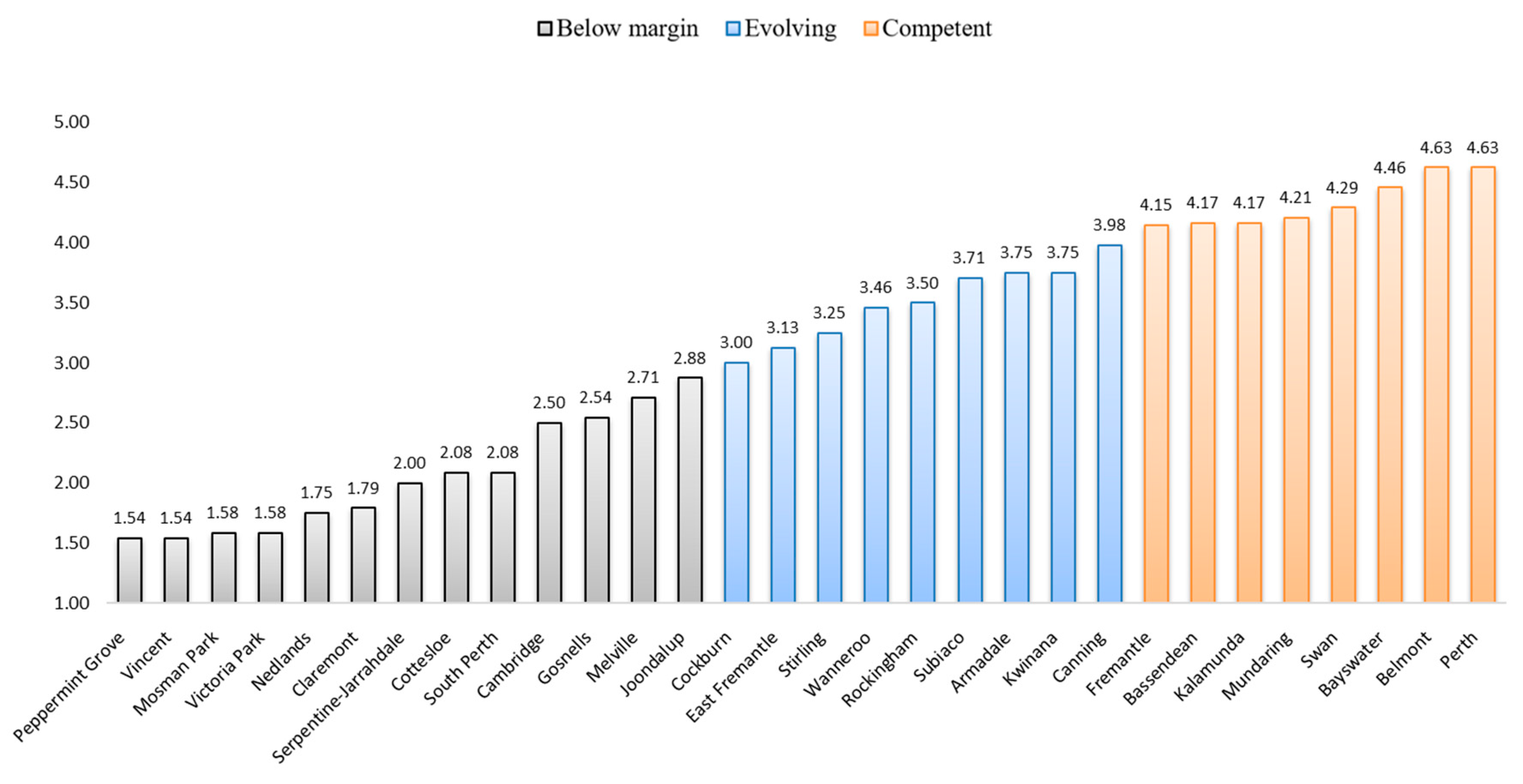

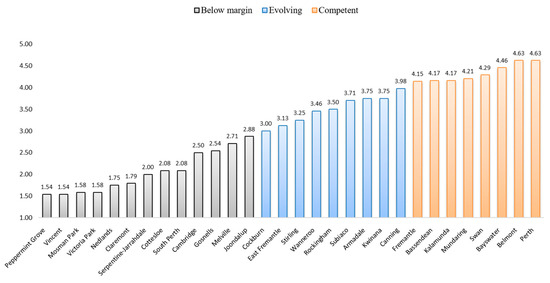

The analysis of the selected policy documents of the city councils in the PMR based on all 12 criteria across four principles revealed an average score of 3.09 (on a scale 1–5), which demonstrated an adoption, just above the minimum acceptable level, of the statewide road safety vision and incorporation of broader considerations. Around 43% of all councils scored below the minimum acceptable level, while another 30% could be classified under the evolving category (scoring between 3 and 4). Only a little over a quarter (27%) demonstrated highly satisfactory performance (scoring above 4) in capturing higher-level policy objectives in their local contexts. The Shire of Peppermint Grove and City of Vincent scored the lowest (1.54), while, on the other hand, the City of Belmont and City of Perth (CBD) yielded the highest average scores (4.63), considering all 12 criteria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average scores of the councils across 12 criteria and positioning within policy integration categories.

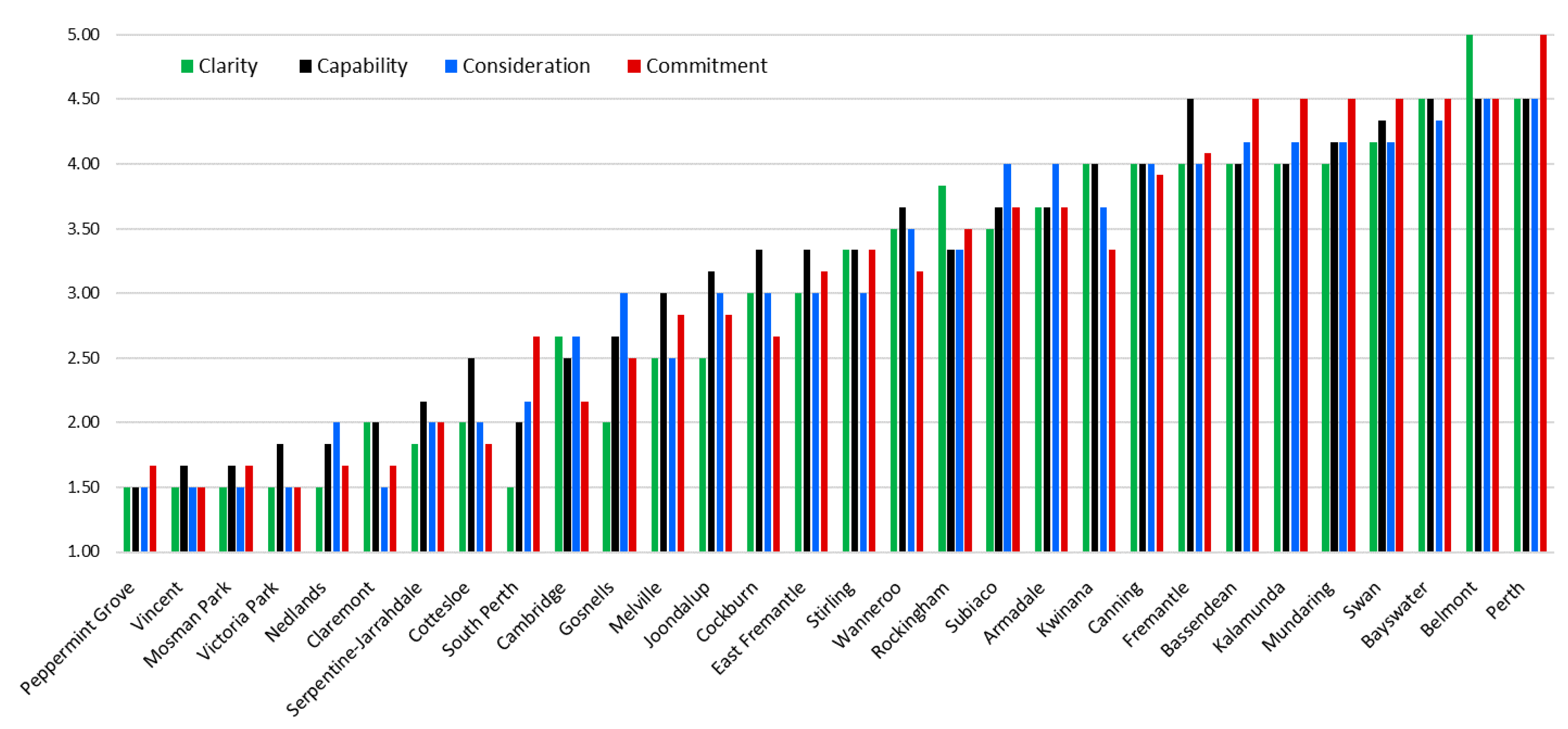

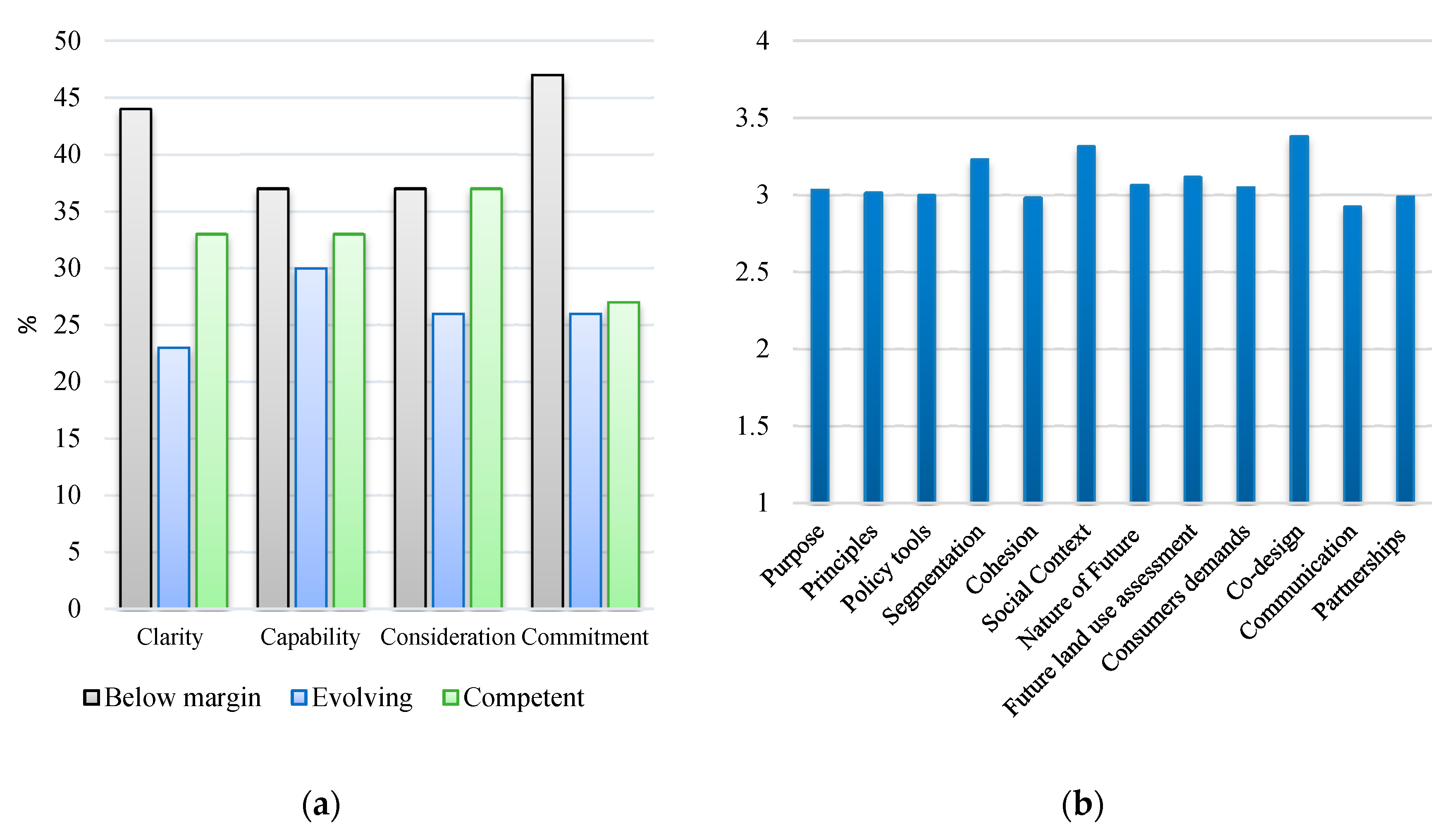

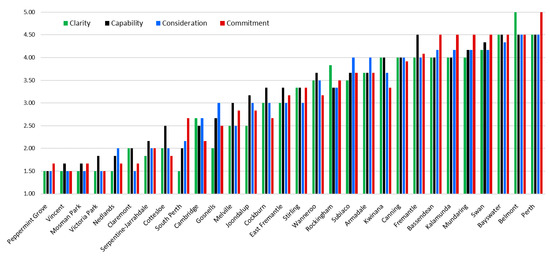

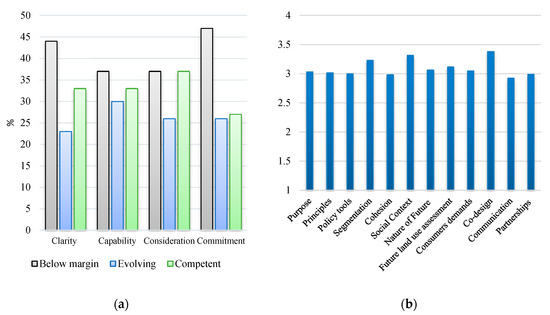

There was not much difference observed in overall average scores across all four principles—clarity, capability, change consideration, and commitment to community engagement (Figure 3). In comparative terms, however, capability scored higher (3.18) with a less dispersed variance (σ = 0.99) than other principles across all local governments. Belmont, Perth, and Bayswater stood out for demonstrating better clarity in terms of translating broader road safety strategies. A high percentage of councils (44%) performed poorly (below the minimum level) due to a lack of clarity in policy documents, while an even higher percentage (47%) of local governments performed just as poorly due to a lack of community engagement in road safety design and management (47%) (Figure 4a).

Figure 3.

Average scores of the councils across four principles (4C).

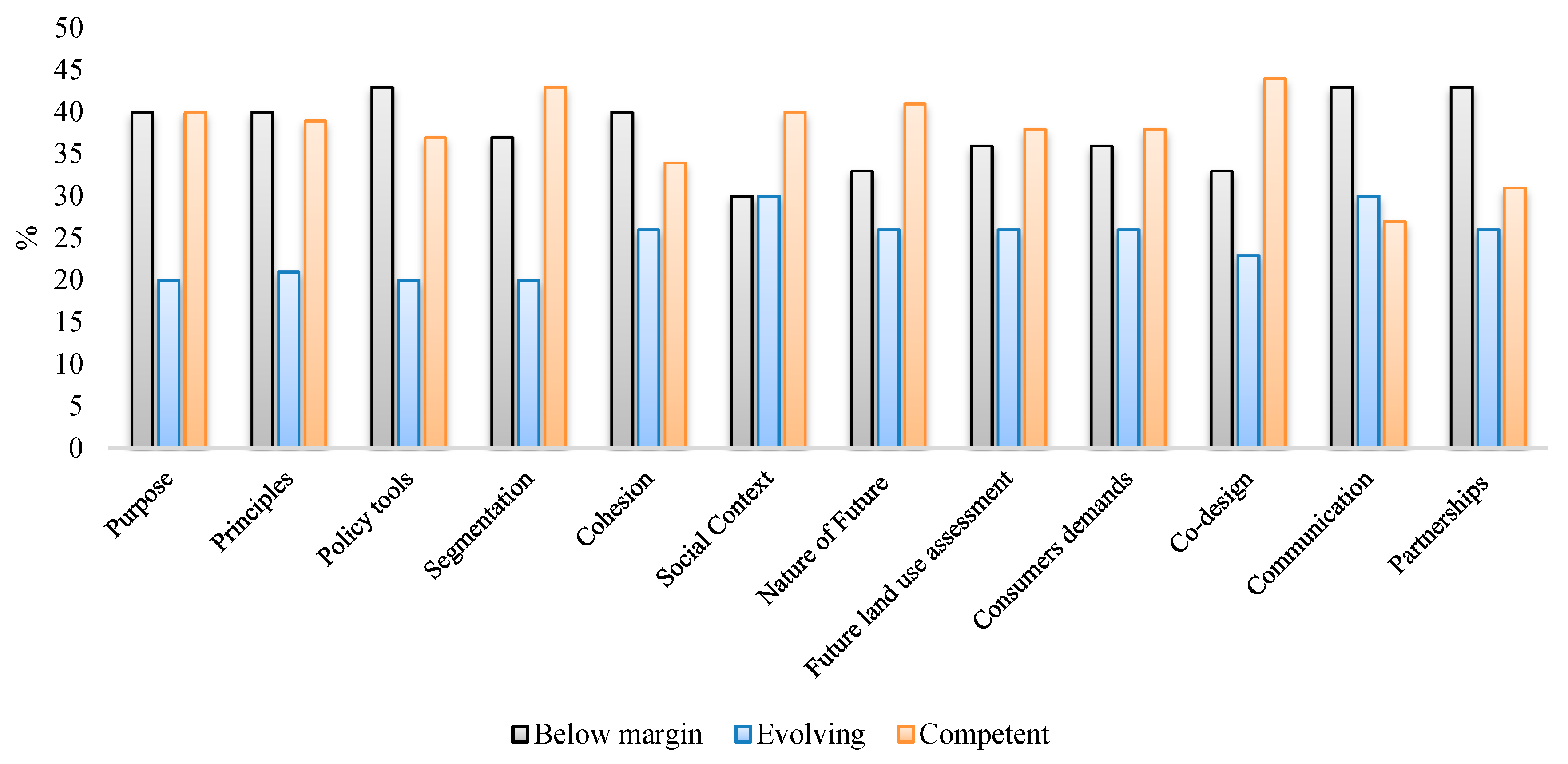

Figure 4.

Performance of the studied councils across the 4C Framework. (a) Distribution of councils across policy integration categories; (b) Average scores across all 12 criteria.

Across the 12 criteria, over 40% of local governments performed poorly (with marginal scores below the minimum expected) in relation to clarity and community engagement (Figure 4b). Interestingly, in communication and partnership criteria under the community engagement principle, comparatively fewer councils received a competence score. Breaking the general trend, Belmont and Perth came across as high achievers with scores of 5—Belmont in clarity and Perth in its commitment to community engagement.

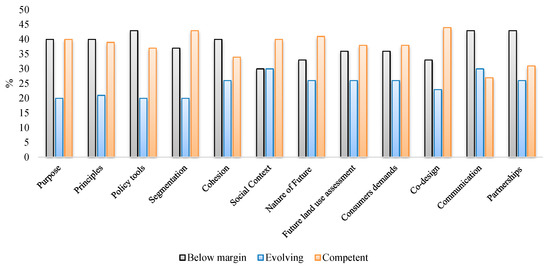

Further analysis of the 12 factors revealed that local government policies performed relatively better in aspects related to segmentation, social context, and co-design (Figure 4b). Meanwhile, the aspect that came across as the weakest in comparison to others related to the communication channel between the councils and the community. In the evolving category, the representation of the councils was observed to be consistently low (20–30%) across all criteria (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Level of policy integration by the councils across 12 criteria.

7. Discussion

The results showed a varying landscape while profiling the extent of the local governments’ adoption of the broader road safety strategies along the 4C dimensions. A lack of ‘clarity’ could account for a significant number of city councils scoring low and seeming to be still struggling to reflect the core ideas contained in the Safe System and Vision Zero principles in their local contexts. Road safety mechanisms continued to rely heavily upon infrastructure and educational measures and less on improving the capability of road users. They continued to lack the ability to meaningfully consider future changes and to effectively engage the community in more inclusive road design. The deficiencies in major policy documents were manifold, including a lack of recognition of road safety issues as well as an absence of details on how to implement relevant programmes and projects to deal with future complexities. For example, Mosman Park (average score—1.58) failed to develop any significant policies of road safety management while its broader planning and policy documents provided little clarity on how local safety issues would be dealt with. On the other hand, while South Perth undertook better initiatives towards integrating local transport to make all suburbs accessible, safety principles were left unattended [61]. It was interesting to observe that a few relatively higher density local government areas located in the inner city ring of the PMR (e.g., Nedlands, Claremont, and Cottesloe) seemed to consider the need for infrastructure, shared movement, and considerations of the local context (congestion, parking, and anti-social behaviour). However, their councils’ policies showed a minimal implementation strategy with no funding structure proposed. A recent study in Claremont, meanwhile, revealed decreasing community awareness of road safety due to the lack of an appropriate education programme and priority in budget development [66].

A number of councils appeared as promising (average scores between 3 and 4) in translating the broader vision into their respective jurisdictions. Councils in this category demonstrated a better motivation by delivering streamlined policy documents for overall transport network management and, in some cases, some specifications on road safety issues. At this evolving stage, the councils close to the periphery of the PMR facing new residential development have started to conceptualise the vision of recent road safety approaches, but have yet to come up with comprehensibility and greater details for implementation. The policy documents of Cockburn (scored 3) clearly indicated long-term guidance for transport planning. The council touched most of the criteria outlined in the 4C Framework. The City of Armadale (3.75) outlined best practice road safety strategies and infrastructural requirements to meet the statewide vision. With similar scores, Kwinana highlighted Safe System and Towards Zero visions and aligned with the ‘Guidelines for Preparation of Integrated Transport Plans’ [62,63]. The available documents provided a broad guideline for a safe and efficient integrated network of roads, footpaths, and cycle routes supported by a good public transport system. Two high achievers in this category, Stirling and Wanneroo (scored 3.25 and 3.46, respectively), demonstrated a higher level of conceptualisation and willingness to apply more specific policy tools to address road safety issues in their jurisdictions. The SCP of Stirling offered a comprehensive outlook on understanding traffic accidents and travel speed. It also considered the future complexity and development trends outlined by the major metropolitan plans (e.g., Perth and Peel @ 3.5 million, Directions 2031, etc.). The policy of Wanneroo captured the concept of safe spaces, centres, and facilities within infrastructure management and designs for community benefit and recreation. Its transport strategy also determined development priority based on future land use and transport demand [67].

The policy analysis identified a number of competent councils that showed higher levels of policy integration in translating statewide vision with reference to ‘considering changing contexts’ and ‘community engagement’. The standout performance of Belmont and Perth city councils can be justified by their strategic location and development priority in the PMR. For example, Perth (4.63) accommodated the CBD and the central transport and pedestrian-friendly shopping hub. The SCP rightly considered land use and infrastructure planning that facilitated a wide range of public and private sector investments. Its ITS suggested significant safety improvements across all modes of transport and committed to the state’s Towards Zero road safety vision. The strategy further aimed to target road safety and future transport behaviour. Similarly, Belmont recently progressed through a large transport infrastructure project and hosted the international airport and intermodal freight terminals [65]. Belmont also appeared as a progressive organisation by taking into consideration future uncertainty (e.g., economic recession and technological changes). Fremantle, another council in this category, proposed the increased priority of sustainability in community perceptions for development interventions. Its ITS proposed road space for cycling that was physically separated from other traffic to ensure safer and shared mobility.

It is evident that councils with regional cooperation in addressing road safety issues had better policy outcomes. The members of the EMRC (Bassendean, Swan, Bayswater, Kalamunda, Mundaring, and Belmont) demonstrated a greater consideration of road safety strategies. Taking road safety as the top priority in the region in the face of increasing population growth and infrastructure development, the EMRC came up with a number of relevant strategies, such as the Regional Road Safety Plan (2020) [53] and Regional Integrated Transport Strategy (2017–2021) [65]. The Road Safety Plan [53] provides

Strategic guidance for the EMRC member Councils’ overarching strategies to support and advocate for the reduction of the number of people killed and seriously injured on roads within the Region in line with the Western Australian State Government’s Towards Zero—Western Australia’s Road Safety Strategy 2008–2020.

The EMRC advocated promotion of pragmatic and comprehensive road safety measures among the member councils that address complex and dynamic land use and behavioural change among vehicle users as well as pedestrians and cyclists. The regional initiatives helped respective local governments to develop policy instruments that cater to local road safety matters and capture the broader vision of road safety management.

In order to achieve a more inclusive road safety management approach, strategic limitations were evident within local policy instruments. While there was a general trend of engaging communities in local planning and design as a prerequisite of sustainable urban development, a positive attitude towards co-design was featured across all development sectors. It did not necessarily ensure a high policy development, and communication and partnership less so—their importance was realised but there was a lack of clarity in communication and partnerships.

Because of the complexity and interconnected land uses, along with the uncertainty and technological change, implementation of the Safe System and Vision Zero principles have remained unsuccessful. Slow adoption and insignificant results in decreasing road crashes in Australian cities indicate similar stories. While there is a global effort underscoring a more inclusive and pragmatic road safety management approach, a great deal of progress still rests upon engineering solutions in achieving the modern road safety vision. For example, the adoption of roundabouts was widely prescribed for local areas in the PMR to deliver the Safe System outcomes that are mostly focused on vehicle occupants. Such an approach definitely has value in risk reduction in intersections, but can be ineffective in various contexts and is unable to respond to other criteria of the framework. The policy instruments in local government should deliver clear guidelines on the transitional pathway to sustainable mobility and Safe System outcomes while respecting local circumstances and promoting shared responsibility.

8. Conclusions

We acknowledge that many programmes and projects contain various overarching strategies and policy guidelines in local government jurisdiction. While the principles of sustainability and community engagement have become the panaceas of local development, road safety is not frequently featured in this context. However, it is contended that there is a greater possibility of eventual adoption of such principles across all councils. The 4C Framework was developed based on the evolution of road safety strategies and emerging concerns. The framework considered mixed-use development in the metropolitan context but is, of course, subject to major disruptions and lifestyle changes. The criteria proposed within the framework will play a pivotal role in promoting a context-sensitive outcome [4], where new technologies, user preferences, and transport systems will emerge in response to unexpected challenges [17,68] that are beyond the scope of even the latest road safety strategies today. This 4C Framework aims to reframe how road safety is viewed and managed in the community today so that it is future-oriented.

As a means of reaching the above objective, we recommend some short-term strategies:

- Undertake more educational programmes through workshops/conferences and roundtable discussions to enable local government planners and engineers to better understand wider policy objectives and their implications in the local context.

- Ensure a clear funding structure for the local governments to channel wider policies into local strategies.

- Conduct studies to understand the popular narratives of road safety policies within the community.

- Work with various stakeholders to develop a shared language of road safety measures to ensure their consistent application across the PMR.

- Along with behavioural control measures, encourage mutual respect and a shared mentality among road users, and motivate them to contribute to road design.

- Councils with an established built environment require to reform their resource management plans to revitalise and restore infrastructure that can accommodate recent sustainable mobility strategies. It is also imperative across the councils to host new technologies in the transport sector.

- Finally, encourage regional cooperation towards managing road safety issues on local roads. It promotes coherent policy translation and shared interventions. Such cooperation can be developed on an ad hoc basis (e.g., Voluntary Regional Organisation of Councils) where a formal regional council is absent.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualised by S.M., who also contributed to the literature review, scoring, and conclusion. M.S.H.S. performed part of the literature review and data analysis. S.K. contributed to the discussion and conclusion sections and overall editing. All authors have contributed in developing the 4C Framework. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the City of Cockburn for sharing road-safety-related data.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Pai, M.; Gupte, T. Next Generation Sustainable Transport Solutions in the Context of the post-2015 Development Agenda. In Proceedings of the 8th Regional Environmentally Sustainable Transport Forum in Asia, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 19–21 November 2014; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Road Traffic Injuries. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Wegman, F. The future of road safety: A worldwide perspective. Iatss Res. 2017, 40, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenzieker, M.P.; Commandeur, J.J.; Bijleveld, F.D. The history of road safety research: A quantitative approach. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2014, 25, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, J.; Stokes, C.; Turner, B.; Jurewicz, C. Towards Safe System Infrastructure: A Compendium of Current Knowledge (Research Report AP-R560-18); Austroads Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, C.W. Using the Haddon matrix: Introducing the third dimension. Inj. Prev. 1998, 4, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddon, W. Options for the prevention of motor vehicle crash injury. Isr. J. Med Sci. 1980, 16, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Safarpour, H.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Mohammadi, R. The common road safety approaches: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peden, M.M.; Puvanachandra, P. Looking back on 10 years of global road safety. Int. Health 2019, 11, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, F.; Berg, H.-Y.; Cameron, I.; Thompson, C.; Siegrist, S.; Weijermars, W. Evidence-based and data-driven road safety management. Iatss Res. 2015, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijermars, W.; Wegman, F. Ten years of sustainable safety in the Netherlands: An assessment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2213, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, P.; Dekker, S.W.; Tingvall, C. The need for a systems theory approach to road safety. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, M.-Å.; Tillgren, P.; Vedung, E. Vision Zero–a road safety policy innovation. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2012, 19, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.; Tranter, P.J.; Warn, J.R. Towards a holistic framework for road safety in Australia. J. Transp. Geogr. 2008, 16, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITF. Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System; The International Transport Forum (ITF): Paris, France, 2016; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B.; Anund, A.; Falkmer, T. The relevance of Australasian road safety strategies in a future context. J. Australas. Coll. Road Saf. 2019, 30, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picton, L.; Bueren, D.V. An insight into the behaviours and attitudes of road users. What does the community really think about Safe Road Use? In Proceedings of the Road Safety Council 2020 Forum, Perth, Australia, 27 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Payani, S.; Hamid, H.; Law, T.H. A review on impact of human factors on road safety with special focus on hazard perception and risk-taking among young drivers. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 357, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakopoulos, A.; Yannis, G. A review of spatial approaches in road safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 135, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, V.; Pinho, P. Evaluation in urban planning: Advances and prospects. J. Plan. Lit. 2010, 24, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyadeen, D.; Seasons, M. Evaluation theory and practice: Comparing program evaluation and evaluation in planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2018, 38, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fylan, F. Using Behaviour Change Techniques: Guidance for the Road Safety Community; RAC Foundation: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.C. The art of interpretation, evaluation, and presentation. In Qualitative Program Evaluation: Practice and Promise; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wilde, G.J. The theory of risk homeostasis: Implications for safety and health. Risk Anal. 1982, 2, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.S.; Pless, I.B. Does risk homoeostasis theory have implications for road safety. Against. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2002, 324, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, F.P. What role should the concept of risk play in theories of accident involvement? Ergonomics 1988, 31, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddon, W., Jr. On the escape of tigers: An ecological note. Am. J. Public Health 1970, 60, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The health belief model. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivis, A.; Abraham, C.; Snook, S. Understanding young and older male drivers’ willingness to drive while intoxicated: The predictive utility of constructs specified by the theory of planned behaviour and the prototype willingness model. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B.P.; Anund, A.; Falkmer, T. A comprehensive conceptual framework for road safety strategies. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 90, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.B.; McDonald, G. Community-based environmental planning: Operational dilemmas, planning principles and possible remedies. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2005, 48, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselwhite, C.; Avineri, E.; Fulcher, E.; Goodwin, P.; Susilo, Y. Understanding Public Attitudes to Road-User Safety–Literature Review: Final Report Road Safety Research Report No. 112; Department of Transport: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, M. Social Psychological Principles:‘The Group Inside the Person’. In Human Factors for Highway Engineers; Fuller, R., Santos, J.A., Eds.; Pergamon: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Christmas, S.; Helman, S.; Buttress, S.; Newman, C.; Hutchins, R. Cycling, Safety and Sharing the Road: Qualitative Research with Cyclists and Other Road Users. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121105052525/http://assets.dft.gov.uk/publications/safety-cycling-and-sharing-the-road-qualitative-research-with-cyclists-and-other-road-users/rswp17.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Granville, S.; Rait, F.; Barber, M.; Laird, A. Sharing Road Space: Drivers and Cyclists as Equal Road Users. Available online: https://www.cycling-embassy.org.uk/sites/cycling-embassy.org.uk/files/documents/Sharing%20Space-%20Drivers%20and%20Cyclists%20as%20Equal%20Road%20Users.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Elvik, R. A theoretical perspective on road safety communication campaigns. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 97, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, L.; Ertel, C. Leadership in a VUCA world: Design strategic conversations to accelerate change. Leadersh. Excell. Essent. 2014, 2, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Declaration of Amsterdam: Cooperation in the Field of Connected and Automated Driving (Navigating to Connected and Automated Vehicles on European Roads); European Union: Brissels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Regulation (EC) No 661/2009 Of The European Parliament and of The Council of 13 July 2009 Concerning Type-Approval Requirements For The General Safety Of Motor Vehicles, Their Trailers And Systems, Components And Separate Technical Units Intended Therefor; European Union (EU): Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soteropoulos, A.; Berger, M.; Ciari, F. Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: An international review of modelling studies. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbaugh, E.; Rae, R. Safe urban form: Revisiting the relationship between community design and traffic safety. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkim, T. Connected and Automated Driving in The Netherlands—Challenge, Experience and Declaration. In Road Vehicle Automation 4; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Quick, L.; Platt, D. Disrupted: Strategy for Exponential Change; Resilient Futures Media: Victoria, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, L.; Kuhnimhof, T.; Trommer, S. Does context matter? A comparative study modelling autonomous vehicle impact on travel behaviour for Germany and the USA. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 122, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapan, M.S.H. Who participates and who doesn’t? Adapting community participation model for developing countries. Cities 2016, 53, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Community participation in road safety policy development and strategy planning. J. Australas. Coll. Road Saf. 2019, 30, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Capano, G.; Howlett, M. The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WALGA. Safe System Guiding Principles for Local Government; Western Australian Local Government Association (WALGA): Perth, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EMRC. Regional Road Safety Plan; East Metropolitan Regional Council (EMRC): Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- RSC. Preliminary summary of fatalities on Western Australian roads 2019; Road Safety Commission: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- TRC. Preliminary Fatality Summary 2019; The Road Safety Commission (TRC): Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McTiernan, D.; Turner, B.; Wernham, R.; Gregory, R. Local Government and the Safe System Approach to Road Safety; ARRB Group Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WALGA. Zones. Available online: https://walga.asn.au/About-WALGA/Structure/Zones (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- BOM. Climate Statistics for Australian Locations. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_009225.shtml (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Rall, E.L.; Kabisch, N.; Hansen, R. A comparative exploration of uptake and potential application of ecosystem services in urban planning. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoW. Strategic Community Plan (2017/18–2026/27); City of Wanneroo: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CoS. Strategic Community Plan (2020–2030); City of South Perth: Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CoK. Strategic Community Plan (2017–2027); City of Kwinana: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CoK. Integrated Transport and Land Use Study; City of Kwinana: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EMRC. EMRC Annual Report 2018/2019; The Eastern Metropolitan Regional Council: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EMRC. The Regional Integrated Transport Strategy (2017–2021); The Eastern Metropolitan Regional Council: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CoC. Claremont Ahead: Strategic Community Plan 2027; Town of Claremont: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Consolidation, Moving People and Moving Freight. In Proceedings of the Regional Transport Forum 2013, Perth, Australia, 8 November 2013.

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, J. What VUCA really means for you. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92. Available online: https://hbr.org/2014/01/what-vuca-really-means-for-you (accessed on 16 July 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).