Abstract

The research’s fundamental investigation elaborates on interactions between tertiary educational factors and Namibia’s sustainable economic development. Sequential mixed-research-method guides the investigation towards its results: A quantitative statistical data analysis enables the selection of interrelated educational and economic factors and monitors its development within Namibia’s last three decades. Subsequent qualitative interviews accumulate respondents’ subjective assessments that enable answering the fundamental interaction. Globally evident connections between a nation’s tertiary education system and its economic development are partially confirmed within Namibia. The domestic government recognizes the importance of education that represents a driving force for its sustainable economic development. Along with governmental NDP’s (National Development Program) and its long-term Vision 2030, Namibia is on the right track in transforming itself into a Knowledge-Based and Sustainable Economy. This transformation process increases human capital, growing GDP, and enhances domestic’s living standards. Namibia’s multiculturalism and its unequal resource distribution provoke difficulties for certain ethnicities accessing educational institutions. Namibia’s tertiary education system’s other challenges are missing infrastructures, lacking curricula’ quality, and absent international expertise. The authors’ findings suggest that, due to Namibia’s late independence, there is a substantial need to catch up in creating a Namibian identity. Socioeconomic actions would enhance domestic’s self-esteem and would enable the development of sustainable economic sectors. Raising the Namibian tertiary education system’s educational quality and enhancing its access could lead to diversification of economic sectors, accelerating its internationalization process. Besides that, Namibia has to face numerous challenges, including corruption, unemployment, and multidimensional poverty, that interact with its tertiary education system.

1. Introduction

The correlation of a nation’s education system and its economic development applies to countries worldwide. The educational aspect within human capital, expenditures into the education sector, and education quality are vital aspects of a nation’s socioeconomic development process [1].

Emerging markets are nations in their progress that have to overcome challenges to lift barriers towards economic growth and raise their global awareness. Apart from industrialized nations, emerging markets are also aware of the connection between education and economic development. However, their challenge deals with raising the necessary resources needed towards taking measures. These necessary resources would substantially improve their education system, which would enhance their transition towards an emerged economy [2].

This research’s primary purpose lies in defining educational factors impacting economic development in Namibia, its development over a defined period, and selected interviewees’ perceptions of their bidirectional relation, following the expertise of OECD [3] and the authors Earle [4] and Marope [5]. Emphasizing tertiary education is highly influential to a nation’s human capital and economic performance [6]. Thus, the authors decided to expand on this research premise focusing on Namibia’s tertiary education system.

This research elaborates on the contribution of relevant educational factors influencing Namibia’s economic development’s emerging market. The desert-country of Sub-Saharan-Africa is on their way towards transforming themselves into a Knowledge and Sustainable Economy by improving the country’s human capital [3]. However, the domestic education system lacks education quality, infrastructure, state-of-the-art curricula, and its accessibility to Namibia’s multicultural society. Apart from these educational challenges, the nation has to face additional socioeconomic challenges, including tremendous inequality conditions, multidimensional poverty, and rocketing unemployment rates [4].

To raise awareness of Namibia’s educational challenges that hinder the nation’s economic transformation process, the authors present internationally applicable interactions and apply them in Namibia’s tertiary education system. This will highlight the Namibian tertiary education system’s current state, its impact on the domestic economy, and further emphasizes educational aspects that hinder the nation from achieving its long-term economic objectives. Possible socioeconomic, economic, and educational challenges will be carved out to develop prospective adequate solution-approaches. This study intends to assist Namibia’s development towards a gateway for the Sub-Saharan-African region, including its sustainable economic development and a state-of-the-art education system. Furthermore, the nation’s international perception and competitiveness should be strengthened in order for them to increase their participation in global trade and their attraction of high-skilled foreign direct investments [5].

A sequential mixed-research-approach guides the research’s methodology: A preliminary quantitative statistical-data-analysis enables selecting the most influential educational factors. The collection and analysis of secondary data enable visualizing Namibia’s development factors in the last three decades. The subsequent qualitative investigation will be executed through interviews. Therefore, Namibians of the nation’s tertiary education system and the labor market will be selected on-site. Through interviews, gathered assessments will partially underline and partially revoke quantitative trends related to this bidirectional relation.

This mixed-research approach gathered data that would primarily answer the primary investigator’s question of interactions between Namibia’s tertiary education system and its economic development. Additionally, this research emphasizes raising awareness of the potential of the emerging market Namibia. In particular, the existing business-economic relations between Europe and Sub-Saharan-Africa should be strengthened by referring to predominant domestic challenges that can enhance the predictability of, e.g., foreign direct investments. Besides, countries with a similar baseline socioeconomic situation are provided with an insight into the critical aspect of ‘Economies of Education.’

2. Literature Review

The aim of this chapter lies in equipping the reader with background knowledge. This will enable an understanding of the subsequent investigation and the intention of the whole research. Therefore, the following consists of various topics: The applicable international interaction of human capital and economic development. This is followed by the labor market perspective on ‘Economies of Education’ and the international tertiary education system. This gets complemented by insights into Namibia’s economic development and its status quo. Conclusively, information about the nation’s tertiary education system, its challenges, and essential aspects influencing the system are provided.

With its educational policies, a knowledge-based economy receives tremendous importance in the current economic environment when targeting sustainable long-term growth and economic competitiveness. Knowledge Economies (KE’s) are building on knowledge as a critical driver for economic and societal development [6]. The sustained use of innovative human capital represents a central aspect of this development process [7]. The following four pillars indicate the fundament of a KE:

- (1)

- Well-trained and educated citizens.

- (2)

- Dynamic innovation system.

- (3)

- State-of-the-art information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure.

- (4)

- Using knowledge to promote economic and social development.

The outcome is always dependent on a nation’s status quo and its transformation readiness towards a KE. However, if these four pillars are well developed, the chances of economic and societal growth are high. This would provide a strategy in combating poverty [5].

2.1. Bidirectional Relation of Human Capital and Sustainable Economic Development

The main factors determining economic progress are linked to the costs, effectiveness, and adequate utilization of a county’s education system [7]. The World Bank emphasizes the bidirectional relation of human capital and economic development. This institute states that the latter is only possible by contributing an innovative education system [5]. The counter issue is that economic stagnation results in educational stagnancy [7].

As mentioned by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), tertiary education makes a significant difference in a nation’s human capital and sustainable economic progress. A majority of its member states record a preferable situation for tertiary-educated citizens in wages or employment chances [8].

This section’s theoretical level does not include a discussion between institutional and systemic options for higher education and development. Neither public versus private funding nor centralization versus decentralization issues are not taken into consideration. All these elements would significantly contribute to the complexity and length of the paper. Therefore, an overview of the bidirectional relation between human capital and national economies follows, by considering various theories and approaches:

- (1)

- The Human Capital Theory, developed by Becker and Mincer in the 1960s, deals with human capital investments and life-long labor market earnings. According to this theory, more significant investments into education and training lead to a higher skill level and more significant efficient usage of existing technologies [9]. It enhances individuals’ productivity, directly increasing economic output [10].

- (2)

- Human capital builds the foundation of any economic system and simultaneously sharpens the nation’s economic identity. It is necessary to professionally manage, strengthen, and increase the performance of an economy. Foreign Direct Investments (FDI’s), for instance, are heavily influencing a nation’s economic performance. FDI is creating employment (business-) expansions and technology diffusions. A nation’s human capital determines if FDI employing high-skilled or low-skilled labor force is being attracted and concludes if these side-effects are beneficial [5].

- (3)

- In 1962, the communication theorist Rogers developed the Diffusion of Innovations Theory, strengthening this bidirectional relation. The theory links the economic capacity to its ability to create and adopt new technologies [11]. The process of adoption describes accomplishing aspects differently than before. This can be executed by purchasing new products based on its innovation and increases significantly through education. The usage of any state-of-the-art technologies/products positively affect an individual’s productivity and the overall economic output. This has been previously mentioned under (1) Human Capital Theory [5].

However, it is necessary to understand unique societies/economies’ individual characteristics to achieve a beneficiary creation and adaptation process of new technologies [12].

- (4)

- A further notable approach is the Knowledge Transfer Approach. This approach focuses on the essential aspect of spreading knowledge through education. Thus, the application of new ideas, products, and technologies is being simplified through education. Additionally, it simultaneously encourages innovation and boosts efficiency [13].

- (5)

- An adequate education system is a rudimentary pillar in the previously described knowledge transfer. To do so, the costs of education guarantee equalization, efficiency, and effectiveness in utilizing educational resources [5]. Additionally, access to educational inputs and institutions builds a direct link to a nation’s economic situation [14]. Once guaranteed, it supports the diminishment of poverty and political instability [5].

Furthermore, a successful education system enables learners to achieve their returns on education. According to Bogdanović and Požega, this is only possible with a demand-driven education system. The system should be committed to being highly agile, building on current absent knowledge, and foreseeing future trends [7]. If feasible, this dynamism will lead to increasingly higher research and development (R&D) activities. This results in creating innovative technologies within a nation [2].

The most substantial development is represented in tertiary and higher education [15]. Tertiary education enhances access to basic science, self-developed, and imported technologies and plays a significant role in establishing key institutions, as, e.g., government, law, financial system, etc. [2]. Throughout each educational level (primary-, secondary-, and tertiary level), input quality is crucial. It enables the regeneration of human capital at a higher level and impacts the domestic economy [7]. It leads to a variety of economic and social benefits, including the economies of international competitiveness, higher returns of investments (ROI) (Krugmann, 2001, pp. 3–36), greater labor-force flexibility, and an increase of business expansions [5].

Societal benefits are further results of a high-quality education system. The agriculture, environment, and health sectors are being optimized and positively impact food production, food security, and adequate nutrition [2].

Marope mentions that the education system’s quality is directly linked to the domestic unemployment rate, whereby tertiary-educated individuals are better off. Often, the unskilled workforce and the young population indicate the most effective unemployment rates [16].

- (6)

- Educational Gender inequalities are leading to a societal disqualification of women in the long run. Limited females’ access to assets, education, employment, resources, and technology are seen as barriers to social and economic development [17]. These limitations strengthen endemic gender gaps [18] and lead to an overall decrease in income per capita of 3.4% [19]. Ozturk (2001) defines women’s education as the most significant investment for economies in transition. It positively impacts the birth and mortality rate and indicates advantageous effects on health and nutrition. A more precise explanation: “a nation which does not educate its women cannot progress” [2]. Further advantages of gender equalities support the decline of corruption and nepotism rates [4]. A gender-wide equal distribution and access to human capital are only feasible by increasing the education quality [20].

The study results [21] show that such factors influence the size and rating of the HDI as urbanization growth, gross domestic product (GDP), gross national income (GNI) per capita, the share of “clean” energy consumption by the population, and business in total energy consumption, the level of socioeconomic development, and R&D expenses.

These theories, approaches, and aspects lead to sustainable economic and societal development while diminishing poverty, inequalities, and unemployment. Since all of these aspects are interlinked with each other, the modification of single ones would not enhance the economic nor the educational situation in the long run [15].

2.2. Labor Market Perspectives on Tertiary Education and Economies of Education

The increasing emphasis put on tertiary education as a driving force for economic development also bears downside effects. The aspect of ‘Economies of Education’ is seen as a beneficiary situation whereby high-skilled positions should be occupied by individuals that can participate and graduate from higher education. Unfortunately, the number of high-skilled positions has not increased as high as the number of tertiary graduates. This mainly stems from a quicker change of an individuals’ non-graduate to a graduate status than compared to a change in the job structure. This tendency also shifted two-tier society from whether educated or not to elite universities’ participants or ‘usual’ universities. [22]

Therefore, global increasing participation rates in the tertiary education sector have led to graduates’ growing unemployment rates. Simultaneously, the occurring international trend of labor markets looking for employees with unique skills that are frequently not thought of within tertiary education systems appears to result in a global problem of universities supply not meeting the labor markets’ demand. According to OECD Directorate for Education and Skills the tertiary education system has to be renewed on an international level. The reinvention process would equip students with a greater awareness of what they need to learn to meet the skills and knowledge of tomorrow’s demand [23].

Besides that, globalization provokes an international competition of university graduates. The application process equals an auction whereby graduates compete against each other, cutting their conditions. Within this process, the aspect of elite university versus ‘usual’ university again comes into effect. In turn, this development implies an impact for the parental generation. They want their children to receive ‘good’ jobs and instead send them to elite universities, which often contain financial burdens [24].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Namibia and Its Education System

In pre-independent times, the importance of education was not anchored in Namibia’s society nor its government. Low educated lecturers, a lack of monetary resources, inadequate infrastructure [23], and apartheid—offering education according to skin-color—led to substandard human capital within Namibia’s society [25]. After national independence in 1990, the education program ‘Education For All’ (EFA) was introduced, allowing education to be included in its reworked constitution. Since then, educational goals of access, equity, quality, and democracy have been part of the domestic government that included these goals into its NPD’s and Vision 2030 [26].

Education became a fundamental right for everyone provoking greater allocation of resources into the sector. Governmental expenditures on education rose fivefold, leading to an adult literacy rate of 80% in the 21st century. Namibia’s developed human capital is the main component in their combat against poverty, inequalities, and strengthening AIDS/HIV [25].

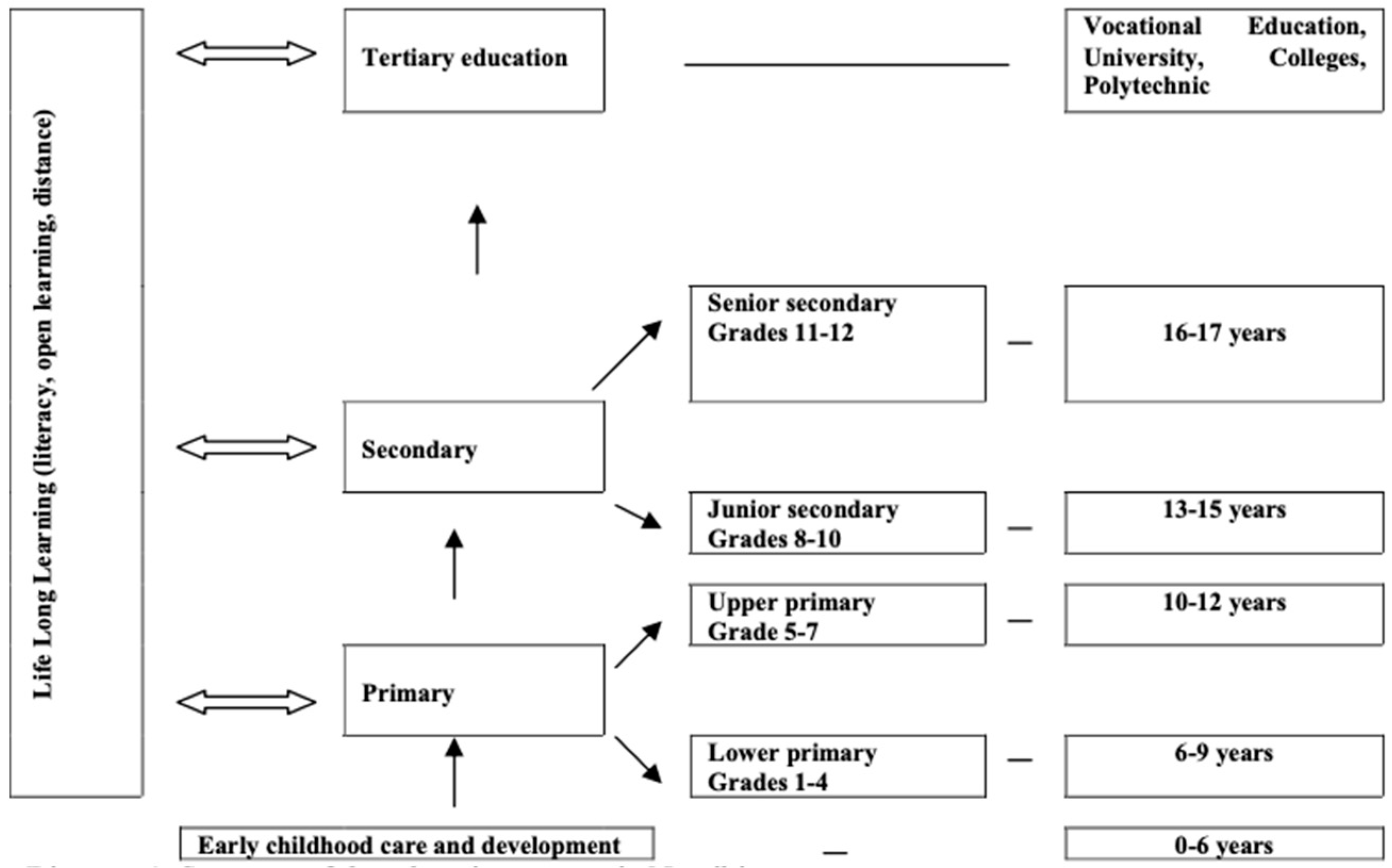

Namibia’s constitution states that all citizens should have the right and access to general education. The so-called 7-3-2 education system, as shown in Figure 1, consisting of seven years of primary, three years of junior secondary, and two years of senior secondary education, as well as tertiary education, should enable the mentioned access [24]. Namibia’s 7-3-2 schooling system is declared as ‘free of charge,’ whereby hidden costs for school uniforms, hostels, or transport bear impoverished families [25]. The amount of government funds for concerned families differs in regions and has been scaled down in previous years. Additional common reasons for children not attending schools are illness, maternal deaths, or being sent to other households for working purposes [24].

Figure 1.

Structure of Namibia’s education system. Source: [26].

Higher education in Namibia gained plenty of attention throughout the last 10 years and represents a critical element of R&D and all types of innovation [5]. In 2016, more than 40 new higher educational institutions (HEI’s) had been established, offering tertiary degrees and post-graduate diplomas [25]. Their majority is located in Windhoek, for instance, Namibia’s leading universities: International University of Management (IUM), Namibian University of Science and Technology (NUST), and University of Namibia (UNAM) [5].

Education became an integrated component within the Republic of Namibia. It represents a critical element of the nation’s transition towards a Knowledge Economic [26] and should help achieve sustainable economic development [5]. Governmental expenditures on education, enrollment rates, and educational institutions are steadily increasing [27]:

- From 2007 to 2015, the percentage of governmental expenditures in education increased from 21.7% to 22.4%. In 2015, the Ministry of Innovation, Arts, and Culture allocated 88% of its budget to the three education levels. This increase indicated an affordability-limit of the upper-middle-income nation Namibia [24]. The latest data of Namibia’s fiscal year 2017/18 represented an amount of USD 1.02 billion being spent on education. However, only USD 208 million had been allocated to tertiary education [28].

- As shown in Table 1, Namibia’s latest result of 2018 indicates 0.645 out of possible 1.0, achieving a medium HDI, which increased by 11.3% since national independence. Namibia’s result is comparable to its neighboring nations’ values and exceeding SSA’s HDI [29].

Table 1. UNDP Human Development Index of Namibia including component indicators in comparison to selected countries and regions 2018. Source: [29].

Table 1. UNDP Human Development Index of Namibia including component indicators in comparison to selected countries and regions 2018. Source: [29].

- The Quality of the Human Development Index includes 14 indicators belonging to HDI’s three dimensions. Namibia’s quality of human development ranked the nation in the third middle section. This illustrates a substantial need to catch up in pupil-teacher ratio, school’s access to the internet, and its Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results in mathematics, reading, and science [29].

- Since national independence, Namibia has achieved an increasing average enrollment rate of 1.7% in primary education. However, Namibia’s learners-population is growing larger. Public Expenditure Review projects an annual growth rate of 0.9% in Namibia’s school-age population until 2050. Although the 2015’s male enrollment was more significant than their counterpart until grade six, female overtook male enrollment from seventh grade onwards. A similar trend applies to the current educational environment [24].

- In 2017, Namibia’s tertiary education system monitored a clear majority of female students, as manifested in the example of domestic’s leading universities: IUM, NUST, and UNAM. The study recorded that 60% of the almost 46,000 student body were females. This particular tendency extends through almost all fields of studies and academic staff [25].

- The latest data of 2015 monitored 28% of Namibian 6-year-old children not attending any form of education. This holds even more true for impoverished and remote families [24].

- The learner positively influences the teacher’s timer per student and the teaching quality to teacher ratio comparing class sizes to the number of teachers in primary education [30].

- In 2015, Namibia’s primary education institutions’ ratio ranged from 5:1 up to 100:1 [24]. The institution’s majority obtained a ratio of 25-30:1, indicating equivalent results when comparing it to average fundamental education ratios of OECD nations: 21:1 in the primary and 23:1 secondary education [30].

- Based on the given data of 1000 pupils attending Namibia’s primary education system, 78 dropouts, 126 repeats one grade, 113 repeats two grades, and 459 learners eventually pass. These numbers result in an input-output ratio of 2:1. The male students are more often affected by dropout or repetition than female ones [24].

- UNDP’s Gender Development Index (GDI) consists of the three HDI dimensions separated by gender: Health, education, and command over economic resources. In 2018, Namibia’s women achieved an HDI value of 0.647; in contrast, men had a value of 0.641. Females exceed males in all dimensions except for the GNI per capita.

- GDI values close to 1.0 represent gender parity, while values close to 5.0 indicate extreme gender inequalities. Namibia’s value of 1.009 places the nation in group one outlining conditions close to gender parity [29].

Consequently, the challenges of Namibia’s education system are the following:

- Although education got included in Namibia’s constitution, its NDP’s, and the nation’s Vision 2030, its education system suffers from inconsistent policies, nonexistent reforms, and unequal regional enforcement [24]. The learners and the education quality are affected, while Namibia’s economy must grabble with the fallout [27].

- The scarce allocation of Learning Support Materials (LSM’s) within Namibia represents an obstacle for learners and the output-quality [30]. Endemic composite classes share little amounts of LSM’s, whereby textbooks need to stay in school and are handed over from one generation to another [31]. The establishment of 2008’s Textbook Policy to achieve a textbook-to-learner ratio of 1:1 tries to improve the domestic situation [32].

- Namibia’s tertiary graduates suffer from low-quality primary education input, leading to unmet national and international objectives [23]. Kamerika (2020) emphasizes raising educational standards, offering personalized learning arrangements, and diminishing educational institutions [27].

- Inferior graduates and a domestic education system not complying with the labor market’s demand negatively affect Namibia’s unemployment rate [33]. Therefore, numerous students choose to study abroad, enjoying superb educational quality and superior employment chances [5]. For instance, foreign institutions, the Millennium Challenge Corporation USA (MCC), are making efforts to improve quality. This is carried out by increasing educational activities and the supply and access to textbooks [5].

- Namibia’s HEI’s ensconce high tuition fees have resulted in affordability [28]. The percentage of 5.5% represents the average household’s spending on tertiary education, which is similar to transport (7.2%) or healthcare spending (6.6%) [24]. Fees have increased over the past and averagely account for around USD 1650 per year [34]. Tertiary education students can apply for student loans from state or private funds. Unfortunately, these funds have also been downsized over the years [27]. Barriers to higher education participation are predetermined and lead to increased enrollment rates of wealthier students [34]. A closer examination of the leading universities’ tuition fees will be expanded later on, including the enrollment differences in higher education per region.

- Due to Namibia’s colossal landmass and its small population, most educational institutions are located in larger cities, e.g., the capital city of Windhoek. Educational accessibility contains a barrier to citizens of rural and remote areas. An endemic unequal regional and system-wide allocation of educational resources worsens the situation [27]. The findings [35] revealed a dependence between the development of e-learning for sustainable development and the upward trend in education’s economic efficiency. The active private capital enables partial reduction of government spending, optimization and improvement of education management, and higher salaries.

Namibia’s ethnic variety bears unequal enrollment in the domestic education system. Affluent ethnicities living in urban areas indicate higher participation rates than disadvantaged ethnic groups of remote areas. Significantly affected are the northern regions of Kunene and Zambezi demonstrated in the following example: Only 1% of Khoisan speaking pupils can pass primary and secondary education while 40% of Afrikaans German-speaking grade one pupil reach grade 12 [24].

This research’s primary purpose lies in defining educational factors impacting economic development in Namibia, its development over a defined period, and selected interviewees’ perceptions of their bidirectional relation. Following the OECD’s expertise, and the authors [15] and [36], emphasizing tertiary education is highly influential to a nation’s human capital and economic performance. Thus, the authors decided to expand on this research premise focusing on Namibia’s tertiary education system. The following three research questions guided the research:

- (1)

- Which main factors of Namibia’s tertiary education system do influence its economic development?

- (2)

- How did the preselected educational factors develop in the case of Namibia since its national independence?

- (3)

- Whether and how do Namibians perceive the bidirectional relation of Namibia’s tertiary education system and its economic development?

Based on the literature review, the relation of a nation’s education system and its economic development depends on many factors. The authors narrowed down these factors by precisely selecting the most essential nine mentioned in the literature. In particular, the UNDP reports on Human Development [29], Namibia’s EFA program [26], and the book ‘Transitions in Namibia Which Changes for Whom?’ [37] emphasized on them.

These nine factors have been organized into three categories in terms of readability and are identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Defined educational factors compound in categories.

The description, visualization, and application of these nine factors on Namibia’s tertiary education system have considered the last 30-year timeframe by beginning with Namibia’s independence until the present date (1990–2020). In addition to these selected educational factors, Namibia’s economic development has been illustrated by two indispensable indices in economic sciences: GDP and GNI per capita PPP. The researchers have interpreted correlating trends of Namibia’s educational factors and the nation’s economic development. The reader’s overall comprehensibility will be strengthened by including comparisons of neighboring and peer nations—countries with similar results. Incorporating the primary and secondary educational levels would go beyond this research’s boundaries. Therefore, a further limitation is not included in investigating individual factors influential degree on Namibia’s economic performance.

3.2. Quantitative Research

The first part of this sequential mixed-research-approach was conducted through quantitative statistical data analysis. The analysis defined and applied preselected educational and economic factors in the case of Namibia. Outlining this conglomerate of indices within the same timeframe enabled answering research questions one and two. The statistical data analysis approach involves collecting, interpreting, and validating data (Statistics Solutions, 2020). Data collection was realized through secondary data on platforms such as World Bank Open Data or UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). The decisive benefit was lying in the already existing amount of data. Other quantitative research methods, as, e.g., surveys, polls, or large-scale interviews, would not have been able to carry out this amount of precise data and would not represent this study’s scope [38].

This quantitative research’s focus lies in defining and outlining Namibia’s development in preselected factors. The data interpretation was closely linked to its presentation. Microsoft Excel assisted perfectly as an additional program. Inconsistent-, limited-, and temporary, not comparable data revealed a multivariable analysis as not reasonable. Quantitative data have exclusively been gathered from reliable-, open-access, and already published sources and are therefore perceived as validated. Namibia’s sources are primarily governmental, so research limitations and biases must be mentioned as a limitation.

3.3. Qualitative Research

Previously outlined quantitative data provided the basis for this qualitative research’s development. Assessments related to Namibia’s tertiary education system, the nation’s economic development, and both aspects’ interdependency enabled answering the third research question.

The advantage of interviews exists in capturing the interviewee’s personal opinion [39]. Guaranteeing consistency throughout interviews represents an essential element achieved by a beforehand written interview guideline (Appendix A). It included 25 questions containing the research aim, participants agreement in recording the interview for research purposes, and Namibia-specific educational and economic aspects.

Before conducting the interviews, the authors tested their guidelines on third-party volunteers to forecast what direction answers would take. This validity check allowed the last modifications and paved the way for the final interview guideline’s version.

The interviewees represented Namibian individuals that were accurately and on-site selected based on the following criteria: Primary residence in Namibia, enrolled in or holding a degree in tertiary education, and knowledgeable about Namibia’s economic performance. This led to the selection of two students, two university lecturers, and two Namibians with a tertiary degree already participating in Namibia’s labor market. While conducting the study, the authors realized that the respondents’ information is repeating, meaning that nothing new is coming out, and they decided to end with the number of six.

Considering Namibia’s predominant aspects of gender inequality and its variety in ethnicities, the researchers decided to interview an equal number of males and females distributed across the knowledge fields. Complementary, the interviewees stemmed from six different ethnicities representing at least a few Namibian indigenous groups within this research. Table 3 provides an overview of the interviewees, including anonymized designation, gender, age, highest educational degree, and occupation.

Table 3.

Overview of interview participants.

Attention was also given to various age covering 29 years with the youngest participant of 22 years and the most majored participant with 50 years. This diversity in ethnicity, gender, age, educational, and occupation background resulted in unique research leading to valuable individual assessments.

The interview participants have been personally and on-site contacted before the conducting of the interviews. They received some necessary information about the research topic, its aim, and why the authors wanted to include their opinion.

Due to Austria/Slovenia and Namibia’s distance, the interviews have taken place via the telecommunication platform Zoom Video Communications. This platform enabled the researcher a face-to-face communication via video—being considered as highly necessary in interviews—and the recording for data collection purposes.

Before conducting the interview, participants were asked for their recording-permission and anonymized their data.

The interviews have taken place in the timeframe of roughly a week—in between the 9th and 14th of July 2020. The interview length was 46 min on average, with the most extended interview lasting 60 min and the shortest 36 min, always depended on the accuracy of given answers. The interview guideline enabled questioning the very 25 questions throughout the six interviews, whereby the individual answer character has not been restricted. Therefore, attention was paid to a diverse question structure, including multiple choice-, rating scale-, and open-ended questions [40].

After the interview, the authors started transcribing the interviews consisting of almost 300 min of audible data in English (~257 min) and German (~43 min) languages. Interviewees’ data that would have concluded their identity have been anonymized within the transcription process, as previously mentioned. The authors decided to make use of a clean verbatim transcription method.

The qualitative approach of a deductive content analysis assisted perfectly in the process of analyzing gathered data. This approach’s purpose provides a clear structure, presents the meaning of collected data, and enables the researcher to compile matter-of-fact conclusions [41]. The individual’s perception of the pre-announced relation between Namibia’s tertiary education system and its economic development could also be obtained. The deductive content analysis consists of the following three steps [42]:

- According to Miles and Huberman, data reduction refers to the process of selecting, simplifying, and transforming transcribed data [43]. Therefore, interview transcripts have been examined several times, allowing possible key-sections and crucial information to be marked. Highlighted data were implemented into Microsoft Excel, which again was utilized as an additional program. Particular emphasis was put on coding, which enabled drawing connections between specific topics.

- The visual step of displaying data allows the researcher to be creative in drawing lines of similar coded topics or areas [43]. Given answers have been categorized and coded in three steps: The main category, followed by a sub-category, and the given interviewees’ statement. Every statement was equipped with a number drawing a line to the interview participant. The categorization and coding process enabled a subject-specific amalgamation of the data. This represented an elementary step in data research and resulted in logical correlations.

- The last step of this deductive content analysis represents drawing and verifying conclusions. This includes recommendations of certain aspects gained from the data analyzation process [44].

Usually, this process gets completed by analyzing qualitative data only. However, within this research, the conclusion-drawing and verification process has been conducted by the conglomerate of all gathered quantitative and qualitative data. The advantage of this summarized data conclusion and verification lay in consideration of all collected aspects and led to the best possible results.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Research

4.1.1. Educational Factors’ Development in Namibia

The applied quantitative Statistical Data Analysis of secondary data provides detailed information about the nine educational factors’ development in Namibia and the progression of Namibia’s preselected economic factors. This conglomerate of factors was outlined and visualized within the same period from 1990 to 2020. This enables the researchers to interpret trends related to Namibia’s tertiary education system’s bidirectional relation and the nation’s economic development while simultaneously building the overall final data interpretation foundation.

- Higher Education Accessibility. Access to higher education represents the first category consisting of the following four factors:

- Tertiary Gross Enrollment Ratio including an Allocation by Gender. This ratio is defined by the number of students enrolled in tertiary education compared to the nation’s population group aged 16 to 21 [45]. The data indicate a steep upwards trend in domestic’s tertiary enrollment ratio from 2008 onwards. However, this includes a growing difference between male and female students’ enrollment. While males’ enrollment ratio settles at around 15%, females’ ratios have increased to more than 30% in 2017 [45,46].

- Higher Education Enrollment by Region. This factor includes Namibia’s 14 regions, its 2015 higher enrollment rates, and its 2011 regional population census. This provides an enhancement in the comparability process [47,48]. Data express the highest enrollment rates in higher education and the most inhabitants in Namibia’s Khomas region. The reason behind this outlier is the capital city of Windhoek, located in this particular region, domiciling Namibia’s largest and most popular universities: UNAM, NUST, and IUM [45,46]. The regions that are located either in the far north or south indicate the lowest enrollment rates in higher education, for instance, Kunene (0.6%) or Karas (1.5%) [47,48].

- Registration Fees of Namibia’s leading Universities. This factor indicates registration fees of undergraduate tertiary education programs of Namibia’s most prominent universities located in Windhoek: UNAM, NUST, and IUM. The conglomerate of all three universities’ registration fees indicates an increasing trend over the past years. Since 2015, UNAM’s registration fees have been almost stable, while NUST and IUM have been steadily increasing. Data produced in 2020 indicate that UNAM has the lowest registration fees (NAD 1.575/USD 106), followed by IUM (NAD 1900/USD 128). NUST exhibits the highest registration fees (NAD 2100/USD 141) and represents the most expensive university within this triplet [6].

- Share of Population with completed Tertiary Education. The last category provides information about the share of Namibians aged 15 years and above, holding an HEI degree. Comparative numbers of Namibia’s neighboring nations Botswana and South Africa have also been implemented into the statistical analysis. Since national independence in 1990, Namibia’s share of HEI degree holders slightly decreased from 1.29% to 0.76% in 2010 [48,49,50,51]. The Patriot—a local newspaper—and World Bank’s book ‘Financing Higher Education in Africa’ presume increasing tuition fees and higher dropout rates as a reason for this tendency [34,48]. In comparison, Botswana has recorded an upwards trend from 1.52% to 2.02% (1990–2010), while SA briefly managed to increase its numbers of graduates in the years 1995–2000, followed by a 2010 fallback below the initial level of 1990. During the same period of Botswana’s increasing tertiary educated citizens (2000–2010), Namibia registered a comparative downwards trend. These results correspond to the literature presented by Rosa and Ortis (2020). The researchers’ findings elucidate that developing nations achieve results below 1% and developed nations, e.g., Ireland or South Korea, record around 30% of HEI degree holders [49].

- Higher Education Quality. The second category represents the quality of Namibia’s higher education and consists of the following three factors:

- Human Development Index

The UNDP’s HDI represents Namibia’s access to education, living standards, and its citizens’ long and healthy life. Throughout the past two decades, the nation’s HDI steadily increased, experiencing a quantum leap between 2010 and 2015. Namibia’s HDI starts with the lowest value in 2000 (0.543) and the most recent one in 2018 (0.645) [29]. Additionally, there is an incorporation of Namibia’s differences in citizens’ expected years of schooling versus its mean years of schooling. The year 2000 represents the most significant gap recorded with a difference of 6.1 years, while 2005 indicates the smallest gap of 5.4 years [29].

- Qualification of Academic Staff

The qualification of Namibia’s academic staff was indicated by their highest obtained educational degree. In 2015, the majority of Namibia’s total academic staff held a master’s degree (32.4%), followed by bachelor (18.7%) and doctoral degree holders (13.1%). Five percent was lecturing with completed secondary education or lower [48]. In 2017, the number of staff members located at Namibia’s three leading universities held the following academic titles in %: UNAM recorded the highest number of Ph.D. and master’s degree holders (76%), followed by IUM with a total of 52%, and NUST (33%) with the least Ph.D. and master’s degree holders. UNAM registered the highest number of Ph.D. degree-holding staff (22%) while the remaining two universities shared similar results: NUST 10% and IUM 8%. The highest number of master’s degrees held by staff was recorded at UNAM (54%), followed by IUM (44%), and NUST lagging far behind with 23% [25].

- Global Ranking of Namibia’s Universities

The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), according to the Shanghai Ranking in 2020 globally, ranks the top 1000 universities according to their quality of education, quality of faculties, research output, and per capita performance. In 2020, none of Namibia’s universities achieved a rank within the ARWU. The whole SSA-region accomplished placing 12 universities from South Africa and Nigeria, whereby the University of Cape Town, South Africa (UCT), obtained SSA’s best place raked at 201. The Webometrics Ranking of World Universities provides a ranking considering only webometric and bibliometric indicators. According to this approach, Namibia’s three leading universities achieved the global rankings 3211 (UNAM), 3621 (NUST), and 15,919 (IUM) in 2019. In comparison, previously mentioned UCT, South Africa achieved rank 276 in the same year [51].

- 3.

- Governmental Expenditures—Unemployment. The third category deals with Namibia’s governmental expenditures and the nation’s unemployment rate, consisting of the following two factors:

- Governments Expenditures on Tertiary Education as a % share of:

- ○

- Total Governmental Expenditures: Namibia’s tertiary education received the lowest allocated budget (2.46%) in 2008, which increased to the highest budget (6.03%) in 2010. The latest available data of 2014 represent a decrease to 3.87% [46].

- ○

- Expenditures on Tertiary Education as % Share of Expenditures on Education: The nation’s tertiary education system received its lowest share (8.66%) in 2002. This did increase to its maximum percentage of 50.6% in 2014 [45].

- ○

- GDP: From 2000 to 2008, tertiary education expenditures as a % share of GDP ranged between 0.84% and 0.64%. A more considerable increase can be found in 2010 (1.93%), followed by a slight drop until 2016 (1.58%) [47].

- Unemployment Rate of Advanced Educated Citizens. Category three’s last factor outlines unemployed Namibians with completed advanced education as a share of the whole labor force within the last decade. Completed advanced education refers to graduates of secondary school and above [43]. Data cover an increasing trend of unemployed Namibians with a completed advanced educational degree. In 2012, there was a minimum of 3.67%, while the latest data of 2018 refer to a maximum of 12.18%. The period from 2012 to 2014 recorded an increase from 3.67% to 5.97%. This is followed by a significant rise in 2016 (11.08%) and 2018 (12.18%), downgrading the situation of advanced educated Namibians [45].

4.1.2. Development of Namibia’s Economic Factors

The second component of this quantitative Statistical Data Analysis outlines Namibia’s economic development with predefined factors in the same 30-year timeframe as previously determined. In general, economic development can be measured in various ways, using a plethora of different indicators. The authors selected the two factors of GDP and GNI per capita PPP$ to indicate Namibia’s economic development for this research.

According to the World Bank database, Namibia’s GDP rose to USD 15 billion in 2019 [43]. This represents 0.01% of the world’s GDP [50]. From 1990 to 2002, the nation’s GDP ranged between USD 2.7 billion and almost USD 4 billion. The years following 2002 experienced a steady increase in GDP to USD 13 billion in 2012 [43]. After a four-year economic recession lasting until 2016, Namibia’s GDP continued to rise and, according to forecasts, should reach the USD 16 billion mark in 2020 [50]. Compared to its neighboring nations and the SSA region, Namibia registers as the smallest GDP. From 2000 to 2019, Botswana’s GDP developed from around USD 14.5 billion to USD 42.5; Angola’s GDP from about USD 53.5 billion to USD 220.5 billion, while the GDP from South Africa increased from USD 347 billion to USD 761 billion [45].

Namibia’s GNI per capital PPP$ expanded almost continuously from 1990 (~USD 6000) to 2015 (~USD 10,500). Unfortunately, this growth was followed by a recession in the subsequent years indicating Namibia’s latest GNI per capita PPP$ at USD 9618 in 2018. This increases by an average annual growth rate of ~1.7% over the recorded timeframe of 28 years [43]. A comparison amongst neighboring nations exhibits the following: From 2000 to 2018, Namibia’s GNI per capita PPP$ surpasses its neighboring country, Angola’s (~USD 3675–6370). However, the country does fail in outperforming Botswana’s (~USD 10,780–16,310) and South Africa’s (~USD 9880–12,230) GNI per capita PPP$. The entire SSA GNI per capita PPP$ is still lower than Namibia’s, indicating its maximum of around USD 3700 in 2015 [45].

4.2. Qualitative Research

Here are the summarized answers of interviewees.

4.2.1. Category 1—Education

- Importance of Education

All interviewees, without any exception, perceive education as highly essential or as a “key part of my life.” Respondent 6 sees education as the primary determinant of families’ economic situation, the personal standard of living. Education enables finding an occupation relatively straightforward and leads to higher prestige within Namibia’s society. Furthermore, Respondent 3 emphasizes education, making the “difference between poor and rich” and “You can do anything with education [...] because knowledge is power”. Respondent 4 goes beyond Namibia’s borders by expressing that studying makes a socioeconomic difference within the current African situation.

- Perception of Educations’ Importance from different Ethnicities, Regions, and Social Class

The interviewees’ assessments regarding educational importance by ethnicities and their cultures have been manifold. Respondents 1, 2, 4, and 6 see no difference in the ethnicities’ perception of educational importance. What they witness is an increasing trend of the importance of education not dependent on individual ethnic groups. Controversially, Respondents 3 and 5 perceive significant disparities in the educational importance of ethnic groups.

- Remote Areas

Respondents 1 and 5 have been concurrent in their opinions: Remote families—also seen as low—have to fight for survival and, therefore, have difficulties perceiving education as highly necessary. If remote students can participate in HEI’s, their performance often exceeds that of urban students.

- Social Classes

Poverty-stricken families represent the lowest segment in the social classes pyramid. Respondent 1, who sees himself as part of the upper-class segment, emphasized that most of Namibia’s upper-class views education as an essential part of their lives. Namibian’s associated with the lower class do not contemplate on education because their struggles deal with “how to survive.” Respondent 5 shares a similar opinion.

- Registration Fees of Higher Educational Institutions

Four out of six interviewees (2, 3, 4, 6) determined registration fees as an access barrier to higher education. Respondent 3—currently enrolled in a master’s program—talked about a huge personal challenge “when doing a master’s that costs around NAD 100,000” (~USD 6000). Respondent 6, the most mature participant who grew up in Zimbabwe, was the first in his family to go to university. The respondent recounted his educational background and emphasized that if tuition fees had been existent back in the days, it would have hindered him from achieving his tertiary degrees.

- Governmental Financial Resources

Governmental financial resources are the most common challenge for Namibia’s tertiary education system and were mentioned by five out of six interviewees. The domestic government is spending massive amounts of money on its tertiary education system, but it does not receive the whole amount (Respondent1, 2020). Respondent 1 also alludes to corruption as one possible reason. Other interviewees see the responsibility in Namibia’s government, providing limited financial resources. Respondent 6 emphasized Namibia’s missing private business sector that usually supports the government—HEI’s in monetary ways.

- Regional Issue

Respondents 1 and 2 define Namibia’s HEI’s allocation as a domestic challenge. The central location of most universities forces students to relocate to the capital city of Windhoek. Satellite offices and distance-study-programs are improving the situation, especially for remote students.

- Education System

In general, Namibia’s education system has been criticized by two interviewees. Respondent 6 describes the South African schooling system—applied in Namibia—as having a different school year distribution. This results in students lacking preparation for the subsequent tertiary education system. In the respondent’s opinion, most Western nations’ British schooling system prepares students excelling in the next phase of their educational career.

- Quality of Tertiary Education

The inadequate educational output was mentioned by four out of six interviewees. Two participants (2, 6) referred to a review of the taught content. The teaching of outdated content does not prepare students for their professional future, nor will it lead to a better output performance (6). Entrepreneurial drive (6), computerization, and the adaptation of the current curricula (4) are a few suggestions mentioned that would enhance graduates’ situation.

On a scale from 1 to 10, whereby 10 represents the highest value, Namibia’s higher education system’s quality was rated at 6.1 on average. The rating of 7 represents the highest value given by four of the interviewees. The lowest given value was 4, supported by the issue of offering unaccredited study programs. Respondent 4, a university lecturer, stated, “I am not impressed at all as far as the quality being concerned.”

- Higher Educational Institutions’ Resources

Respondent 5 refers to the problem of HEI’s not being able to cater to its students. The respondent mentioned small classrooms, meager amounts of study areas, crowded hostels, and poor technical infrastructure. Another interviewee brings up universities’ substandard entry requirements resulting in students dropping out and high failure rates.

- Gender allocated Higher Education Institutions’ Enrollment Rates.

Respondents 3 to 6 view a current trend of more female students enrolled in higher education than their counterparts. Respondents 3 and 6 attach a better performance to female students because of their hard-working-attitude, while male students are described as looking for “quick-money.”

- Preference or Discrimination of Students according to their gender

Four out of six interviewees do not perceive any advantage or disadvantage status of students according to their gender. There are efforts underway that move towards the equal treatment of students regardless of gender.

- Gender-Specific Drop-out Rates in HEI’s

Four interviewees share the same opinion of an increase in male students dropping out than females. High societal expectations placed on males make them “feel like they have to make quick money.” This is one of the opinions that was stated as a possible reason for the male dropout rate.

- Gender-Specific Graduation Rate at HEI’s

Except for Respondent 1, all interviewees share the coherent opinion of more female students who graduate from universities than male ones.

- Job Finding Process for Graduates

The process of finding a job after graduation did not represent a barrier for four out of six interviewees. Respondent 5 refers to the tertiary degree’s specialization is highly crucial for the job finding process. Besides, the aspect of tribalism was raised. Frequently, Namibians of the same ethnic group or the immediate family have unspoken privileges over citizens who possess specified qualifications.

- Reasons behind increasing Unemployment Rates of Higher Educated Namibians

Unsatisfactory educated graduates who lack career guidance during tertiary education are the representatives of the two causes of Namibian graduates’ increased unemployment rates. Additionally, Namibia’s economic recession, its shrinking labor market, and the labor market cannot manage, as three respondents mentioned, the number of graduates.

- Perceived Connection of Namibia’s Tertiary Education System and its Economic Development

All participants recognized a link between Namibia’s tertiary education system and its economic development. Respondent 6 mentions, “education is supposed to provide […] the human capital of the country” and “the necessary skills that are required for the country to grow and develop.” The Namibian government is generating efforts towards improving educational quality resulting in the expected economic growth in the long run. Respondents 2 to 5 emphasized high-quality graduates as enabling Namibia’s economic situation by creating business opportunities or occupying high positions. Increasing unemployment rates represent the downside of deficiently educated graduates provoking sky-rocking crime.

4.2.2. Category 2—Economy

- Namibia’s Economic Performance 1990–2020

Over the last 30 years, Namibia’s economic performance was most often described as ‘pretty good’ out of the four answer possibilities: Very good, pretty good, pretty bad, and very bad. Healthy development occurred in agriculture, tourism, education, health services, infrastructure, and social services.

However, Respondents 1 and 4 described Namibia’s economic development as ‘pretty bad.’ Namibia is not a hard-working nation and “does not have the culture of working.”

- Aspects affecting Namibia’s Economic Development

Corruption was predominantly the most frequently mentioned aspect of restraining Namibia’s economic development. Namibians are described as self-centered and selfish. The nation’s abundance in mineral resources that could improve Namibia’s modestly sized population ends up in individuals’ or foreign MNE’s hands.

The historical period of colonialization and the late nation’s independence was mentioned by Respondent 1 as an influencing factor to the lack of economic development. Namibia still relies heavily on foreign nations and needs to take its time to develop on its own. In particular, infrastructure and industries are missing, while currently existing ones are majorly owned by South Africa.

4.2.3. Category 3—Scaling Questions: Impact of predefined Educational Factors on Namibia’s Economic Development

The following data were gathered through scaling questions and referred to the interviewees’ perception of how vital predefined educational factors impact Namibia’s economic development. The numeric scale contained numbers from 0 to 10, whereby 10 represented the highest possible impact.

- Government’s Tertiary Education Expenditures impacting Economic Development

Throughout the scaling of these questions, interviewees allocated the government of Namibia’s tertiary education expenditures as the least significant degree of 6.83 on average. Respondents 1, 3, and 4 perceived a relatively high impact on the domestic economy by allocating an 8, while Respondent 5 rated its impact as a 5.

- HEI’s Registration Fees impacting Economic Development

Interviewees’ assessments with the average impact of HEI’s registration fees on economic development coming to an 8. Respondents 1 and 6 referred to the highest possible impact of 10, while Respondent 5 assigned the lowest value of 5.

- Tertiary Education Enrollment Rates impacting Economic Development

The economic impact of tertiary education enrollment rates was rated with 7.5 on average. Respondent 5 allocates the highest possible impact of 10. However, Respondent 3 assigned the least impact by giving a response of 5.

- Share of Population with completed Tertiary Education impacting Economic Development

Interviewees refer to the population’s highest impact on tertiary education on domestic economic development by allocating 8.3 on average. Respondents 3 and 5 assigned the highest possible impact of 10, while Respondents 2 and 6 decided to rate its impact with a 7.

- Unemployment Rate of Advanced Educated Citizens impacting Economic Development

The average impact of advanced educated Namibian citizens’ unemployment rate on domestic economic development was 7.67. Respondents 1 and 6 allocated the importance of 9. Respondents 3 and 5 assigned a value of 6 on this topic.

4.3. Interpretation of Gathered Data

Namibia’s outlined and visualized factors enabled answering the first two research questions and facilitated the researchers’ data interpretation related to the nation’s tertiary education system’s interdependency and economic development. Research question three got answered by the interviewed interviewees’ assessments underlining and partially revoking the literature mentioned interdependencies between those two aspects. The underlying represents the interpretation of the gathered data:

- Perception of the Importance of Education

The literature described educational importance for any nation’s development reflected by the interviewees referring to Namibia’s emerging market. On the one hand, education was mentioned as a key-aspect enabling an improvement of individuals and the entire family’s living standard. On the other hand, respondents pointed out challenges faced by higher educated individuals: They often feel responsible for relatives leading to intra-familiar dependencies as a heavy burden for their own lives because of all the hope of support and the entire family’s financial resources put onto them.

- Ethnicities perception of education

Some interviewees have also confirmed historical and culturally determined differences of ethnicities perceiving the importance of education. They emphasized specific ethnic groups of remote areas being more likely occupied with their daily struggle for survival rather than perceiving the importance of education, which appears as not (yet) essential for them. Other interviewees recognized a more general increasing trend in the perception of educational importance throughout Namibia’s cultures, ethnic groups, and regions.

- Interdependency of Namibia’s Gross Enrollment Ratio, Human Development Index, Government Expenditures on Tertiary Education, and national GDP

According to the literature, increasing citizens’ knowledge leads—amongst many other aspects—to higher productivity, influencing the nation’s economic output positively [10]. Data analysis of Namibia’s corresponding factors and numbers indicate a trend confirming this interaction:

- -

- From 2006 onwards, a parallel upward trend is visible in Namibia’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio—most notably the female enrollment—and the nation’s HDI. This favorable development represents a glimmer of hope in the future reduction of female discrimination in Namibia’s educational context, initially described by literature [16]. This would also prevent the associated forecast in a declining income per capita in the long run [18].

- -

- In almost the same period (2002–2012), Namibia’s economic output nearly rose fourfold. Concurrent to its economic upswing, the nation registered increasing governmental expenditures on tertiary education as a percentage share of education expenditures.

These developments lead to the assumption of mutual influence: Namibia’s economic upswing resulted in higher tertiary government expenditures into tertiary education, which increased the tertiary enrollment rates and positively impacted the nation’s HDI.

- Increasing Registration Fees as Access Barrier versus Increasing Enrollment Rates

The literature described and the interviewees’ assessments confirm the concern of high registration fees representing an access barrier to tertiary education. This tendency probably further impacts the number of tertiary-educated Namibian’s negatively and strongly promotes Namibia’s universities’ two-tier society. Controversial to Namibia’s increasing registration fees are the nation’s ascending tertiary education enrollment rates. Therefore, the impact of high registration fees leading to a decreasing trend of student enrollment cannot be deduced from Namibia’s quantitative gathered data.

In terms of gender, some interviewees perceive a higher share of female students enrolled in tertiary education than male students. This tendency got explained by the female’s diligence and hard-working attitude. Apart from that, other interviewees observe the rather conventional role attributed to Namibian females described whereby women’s duties are to stay at home and look after her family.

- Increasing Enrollment Rate versus Decreasing Academic Graduates

Besides Namibia’s increasing tertiary enrollment rates, the nation experienced a controversial trend of declining tertiary educated citizens. The literature announced decreasing governmental subsidies for students, the high socioeconomic pressure put on educated individuals, and the high share of Namibia’s remote population with limited access to HEI’s could be possible reasons for Namibia’s shrinking number of graduates. Apart from that, the interviewees’ stated that limited offered study programs within Namibia’s tertiary education system forces students to study (-further) abroad, leading to a loss of human capital.

Furthermore, most interviewees recognize an increasing dropout rate amongst male students and attribute this tendency to the high social pressure of “have to make quick money.” The reason for female students discontinuing their studies is more likely to be seen in pregnancy or the rejection of tertiary education by their male partner. This indicates a predominant allocation of conventional gender roles even among tertiary-educated citizens in Namibia.

- Interdependency of Educational Quality, Governmental Expenditures, and domestic’s Economic Output (GDP)

The shortcomings of Namibia’s tertiary education systems’ quality are identified by most of the interviewees. They relate the predominant lack of quality to missing infrastructure, existent non-accredited curricula, and graduates’ little educational output. These mentioned issues are also reflected by the nation’s universities’ position in the international ARWU ranking. ARWU indicates that Namibian universities are not part of their global top 1000 universities’ ranking, referring to low quality in education, faculties, research output, and students’ performance (Shanghai Ranking, 2020). Moreover, the investigation on domestics’ academic staff’s qualification resulted in entirely 5% lecturing with secondary education or lower only.

Besides, from 2010 onwards, governments partly stagnating, partly declining tertiary education expenditures as a % share of GDP and expenditures into the education sector may indicate an implausible adaptation of domestic’s universities’ standards onto the level of international universities. Further, interviewees mentioned characteristics, such as the low motivation of academic staff to improve the tertiary education system or the missing internationalization of domestic universities, that strengthen this correlation.

Interviewees rated Namibia’s tertiary education system’s quality with 6.1 out of 10 on average, whereby one interviewed university lecturer pointed out: “I am not impressed at all as far as the quality being concerned.”

The conglomerate of mentioned aspects leads to an inferior educational quality in Namibia’s tertiary education system, provoking graduates’ backslide with degraded educational outputs. Unfortunately, the literature mentioned developmental dynamics of defective educational outputs, students’ poor preparation for the labor market, inadequate employment compared to the field of study, increasing unemployment rate of graduates, and entailing little economic output, and these are being confirmed by quantitative as well as qualitative data and therefore hold in the case of Namibia.

- Interdependency of Namibia’s Number of Graduates and domestic’s Standard of Living (GNI per Capita)

The literature described the connection between tertiary education and an improved living standard—mainly accomplished through R&D, innovation, and new technologies [2]—and these cannot be confirmed within this research’s gathered data. The comparison between the number of Namibian academic graduates and the nation’s GNI—indicator for standard of living—turns out to be suboptimal due to inconsistent data from partially different periods. However, between 2000 and 2010, an increasing GNI trend by about 25% can be detected, while the share of Namibians with completed tertiary education dropped from an already low level (1.25%) to less than 1% (0.76%). This means that other factors that are not part of this research are accountable for Namibia’s increasing GNI in that period.

Further indications of this connection can be found within the qualitative assessments of interviewees: All respondents see the interference of Namibia’s tertiary education system, in addition to that associated higher standard of living, and a resulting improved economic development.

Also, interviewees perceive the quantitative outlined increasing unemployment rate of tertiary educated citizens emerging from lacking career guidance and the unsatisfactory contribution of company-specific skills in Namibia’s tertiary education system.

The nation’s economic recession, including its shrinking labor market, leads to the supplementary suboptimal integration of tertiary graduates. Furthermore, interviewees mentioned that the attractive Namibian FDI is relatively capital intensive and does not create domestic employment.

5. Conclusions

This research’s primary purpose lies in defining educational factors impacting economic development in Namibia, its development over a defined period, and selected interviewee’s perception of their bidirectional relation. Following the OECD’s expertise, and the authors Earle [15] and Marope [5], emphasizing tertiary education is highly influential to a nation’s human capital and economic performance. Thus, the authors decided to expand on this research premise focusing on Namibia’s tertiary education system.

Based on the literature review, the relation of a nation’s education system and its economic development depends on many factors. The authors narrowed down these factors by precisely selecting the most essential nine mentioned in the literature. In particular, the UNDP reports on Human Development [29], Namibia’s EFA program [26], and the book ‘Transitions in Namibia Which Changes for Whom?’ [37] emphasized them. In terms of readability, these nine factors have been organized into three categories. The description, visualization, and application of these nine factors on Namibia’s tertiary education system have been considered in the last 30-year timeframe by beginning with Namibia’s independence until the present date (1990–2020).

A nation’s human capital—generated by its education system—represents a vital aspect of a nation’s economic development process. This interaction, also named ‘Economies of Education,’ is mainly dependent on the education system’s quality, expenditures in the education sector, resources and fair allocation, and societal accessibility. If these aspects are given, there is little to prevent a nation from progressing economically [1]. The effects of increasing R&D, usage of efficient technologies, increasing productivity, raising human capital, improved standard of living, and greater economic output, are leading towards economic development [5]. The tertiary education sector has a massive impact on this process compared to the primary and secondary-education level [8]. However, the labor market perceives challenges with the current tertiary education systems. Universities put too much emphasis on their competition with each other. Low quality and unmet labor market preconditions are the consequences. The situation for tertiary graduates is even worse. Their education returns are often not given while they are being equipped with skills that are mostly not needed for their subsequent professional career.

This study’s fundamental research deals with the Namibian tertiary education system’s interaction and the nation’s economic development. This interaction got elaborated through the following research questions using a mixed-research method:

- ○

- First of all, Namibia’s tertiary education system’s most influential factors impacting the nation’s economic development have been identified (RQ1). The development of these preselected educational and economic factors has been elaborated through quantitative statistical data analysis.

- ○

- This enabled the researchers to outline and monitor these factors since Namibia’s national independence—30 years ago (RQ2).

- ○

- Participants of Namibia’s tertiary education system and the nation’s labor market have been interviewed using qualitative interviews—about their perception of preselected factors, including the factors’ interaction (RQ3). Respondents’ subjective assessments supplemented the previously gathered quantitative data and enabled answering the research’s fundamental interaction.

The literature initially reported the correlation between a nation’s education system and its economic development—‘Economies of Education’—partially holds for Namibia and is heavily dependent on education quality.

The results of qualitative interviews confirm the educational importance being main determined for Namibia’s goal of sustainable economic development. Education and its quality are seen as key-aspects, whereby perception differences among Namibia’s ethnic groups are existent. Unfortunately, these different perceptions reinforce the unequal allocation of HEI’s and result in lower participation rates of certain ethnic groups.

The conglomerate of research data indicates numerous challenges for Namibians participating in the domestic’s tertiary education system. This includes a lack of universities’ infrastructure, inadequate curricula, and limited international expertise.

According to the authors, Namibia’s resulting consequences are students’ funding issues, increasingly high dropout rates, and poorly prepared students for the subsequent labor market. The latter aspect was already mentioned in the literature, emphasizing the problems of tertiary education systems. Further problems in Namibia’s case are tertiary institutions focusing on their competition rather than meeting the domestic labor markets’ demand. Namibian students’ consequences are not earning rewards that they expected and having little chance in their education returns. A further problem in Namibia is the shift in human capital due to students studying abroad and often staying there. However, this lost human capital would be essentially needed for the emerging market of Namibia.

Interestingly, though, despite all the hurdles, Namibia’s enrollment rates in tertiary education are increasing, especially female students. In turn, Namibia’s increasing unemployment rates among academics lead to the conclusion that the domestic economy is not yet prepared for university graduates.

Due to Namibia’s late independence in 1990, the authors see a substantial need to create a Namibian identity. Socioeconomic actions would enhance domestic’s self-esteem and would enable the development of sustainable economic sectors. Raising Namibia’s tertiary education system’s educational quality and enhancing its access could lead to diversification of economic sectors, accelerating its internationalization process. A concurrent strengthened domestic economy would also be beneficial in Namibia’s governmental combat against predominant multidimensional poverty. On top of that, urgently needed political and socioeconomic reforms would privilege domestic businesses instead of multinational MNE’s. These steps would increase the international perception and competitiveness of Namibia. This would lead to FDI that supports the domestic development process, rather than exploiting the nation, and would create adequate employment for Namibian academics.

Although there is a vast amount of government expenditure into Namibia’s education system, its effectiveness is limited by factors, e.g., corruption or unequal distribution. Even the increasing budget for tertiary education can only develop its full potential if an adequate and nationwide fair distribution of funds is guaranteed.

The world population has been increasing, people live longer, and quality of life has improved [51]. Nevertheless, the authors would like to point out certain aspects that further strengthen Namibia’s path of using human capital as a guiding force in achieving sustainable economic development:

- ○

- The formulation of long-term goals within the nation’s NDP’s and its Vision 2030 are prosperous first steps that would need to be accompanied by a scientific evaluation process improving the implementation process.

- ○

- Furthermore, the authors suggest continuing combating against predominant corruption. For instance, this would enable adequate allocation of educational expenditures or make Namibia’s tertiary education more affordable for all ethnicities and social classes.

In conclusion, the authors want to emphasize the aspect of cohesion-thinking: Namibia’s multicultural society and its differences in ethnicities, values, and habits will probably decisively accompany the nation’s socioeconomic upswing in the upcoming decades.

Further research regarding the increasing enrollment rates and the concurrent growing registration fees is needed for an even greater understanding of the mechanisms between Namibia’s tertiary education system and the nation’s economic development. Additionally, the contrary domestic decreasing number of graduates—especially male students—while increasing enrollment rates appears to be an interesting subject for future studies.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis was conducted by M.J., methodology provided by T.H., and supervision by V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Guideline

- (1)

- Due to the anonymization of this interview and the following transcription process, could you please tell me your Gender and Age:

- (2)

- Just general information from your side:

- -

- What is your educational background, and what do you currently do for a living?

- (3)

- I would like to start with some questions about education in general.

- -

- What personal importance does education have for you?

- -

- What importance does education have in different ethnicities and social classes? Are there any differences visible? If so, which ones?

- (4)

- Now I would like to ask you a few questions about the tertiary education system in Namibia:

- -