1. Introduction

Community is a broad concept. In planning, the core connotations are often linked with concepts such as residences, places, and social groups. Here, community refers to the sum of interconnected communities and their activity spaces formed by gathering several social groups and organizations in a specific geographic area. As an essential component of a city, healthy and sustainable community development has become a global proposition. Urban planning research has always focused on community planning. From the early “neighborhood unit” planning concept that involves creating a safe and convenient community living place [

1], to community renovation for space renovation under the development model of “urban regeneration” [

2], to the deep involvement of citizens and social power in today’s community development under the idea of “comprehensive planning” [

3], community planning has experienced a changing development process from top-down to bottom-up development, i.e., from government-led development to spontaneous citizen-led development.

After the reform and opening of China, the country has experienced profound changes in its economic and social structures and has put forward higher requirements for improving its comprehensive social governance capabilities. In 1993, the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) changed the term “social management” to “social governance”. In 2013, the CPC’s Central Committee’s Urbanization Work Conference put forward the idea that “urbanization is not only a problem of macro-layout, but also a problem of micro-urban space governance.” In 2017, the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China put forward the development goal of “social governance of co-building, co-governance, and sharing.” The main body of community governance in China has gradually expanded beyond the government, and the governance process is no longer limited to solely top-down management and control. Based on the theoretical and practical achievements of community governance and community planning in various countries, China’s exploration in this field has also attracted wide attention from scholars, both at home and abroad. Existing research has focused on the interactions and influences of various community governance subjects in the process of public participation in community planning [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], as well as the influencing factors of community planning [

9], the working methods [

10], and the roles and mechanisms of community planning and dilemmas [

5,

11]. In China, the power of various stakeholders in community planning is not balanced. Simple top-down or bottom-up community governance cannot adapt to China’s unique national conditions. Therefore, it is imperative to propose a community planning mechanism with Chinese characteristics. Many scholars have also pointed out the gap in public participation between developing and developed countries and have realized that there is no universal public participation mechanism [

11]. Furthermore, the integration of community planning with urban regeneration planning and disaster prevention planning is an important issue [

12]. Existing research is mainly based on empirical cases that are supplemented with theoretical discussion. Through the investigation of community planning and public participation in different social backgrounds around the world and the discussion and derivation of theoretical frameworks, both a diversified community planning system and public participation mechanisms have been established.

As an essential component of modern urban planning, public participation originated in the United Kingdom in the 1940s [

13] and was introduced to China in the late 1980s. After more than 30 years of development, Chinese-style public participation has shown a certain degree of inadaptability [

14,

15]. On the one hand, the government has expanded the breadth and depth of public participation in urban planning with no efforts spared; on the other hand, citizens generally have low trust in participatory planning. This contradiction is particularly prominent in community planning, which is closely related to the daily lives of Chinese citizens [

14,

16]. Based on the research on the differences in social governance between China and Western countries, this study analyzed the underlying reasons for the existing problems and proposed working ideas and practical methods for participatory community planning that are suitable for China’s national conditions.

As a developed city on the eastern coast of China and member of the first batch of participatory community planning pilot cities, Xiamen has explored many aspects of community renovation, such as changes in the roles of the government and planners, the selection of public participation units, the design of public participation plans, and the investigation of the role of community organizations. This study took Zengcuoan in Xiamen as an example, focusing on establishing a system of public participation in community planning and determining the participation units. The following research questions were proposed: What are the reasons for Chinese-style public participation? How should a reasonable public participation unit be defined in urban planning? What are the characteristics of public participation in community planning? What makes a collaborative pattern effective in the process of public participation in community planning?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 traces the origin of the basic concepts of public participation and reviews the relevant theories and practices of public participation in urban planning.

Section 3 focuses on the subjects and units of public participation in urban planning and the importance of public participation in community planning.

Section 4 takes Zengcuoan in Xiamen as an example to introduce the specific application of collaborative workshops in participatory community planning.

Section 5 discusses the collaborative model’s application value in public participation for community planning and the relevant inspiration of this research and then draws the final research conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Participation

2.1.1. The Concept of Public Participation

“Public participation” can be thought of as “public involvement” or “civic engagement” in the field of sociology. The former refers to involvement that is shared, social, and belonging to everyone, and emphasizes social attributes; the latter refers to social groups who face the same problems, share the same interests, and have the same requirements when connecting and functioning with subjects related to the public, and emphasizes personal attributes. Compared with public involvement, the composition of the collective taking part in civic engagement is diverse, and the process emphasizes and values the individual demands of members. In sociology, “public participation” is defined as “purposeful social actions within the scope of the rights and obligations of social masses, social organizations, units, or individuals.”

The term “public” originated from ancient Greece. It means that under a city-state government, citizens could express their personal views and participate in political life, formulating public policies via democracy. The land and its appendages in Western countries are all privately owned. Based on their maintenance of “privacy,” multiple stakeholders seek to reach a consensus on the allocation of interests through joint consultation. Therefore, democratic decision-making has gradually become the primary mode of social governance in Western countries. The so-called “public” in these countries is produced by “private” entities and exists to maintain “privacy” [

17,

18]. The situation in China is different. Due to the influence of long-term feudal autocracy, “public” is usually equivalent to “official” or “government,” and “private” generally refers to “people” or “individuals.” Under the dominant public value of working selflessly for the public interest, public power is magnified and private power is ignored. “Public” becomes something that is imposed on citizens after being monopolized by the government, and publicity becomes a particular attribute attached to government behavior. Urban planning, which aims toward coordinating public interests, is closely related to the lives of citizens. Information is an essential factor that empowers urban planning. Therefore, the selective dissemination of information can affect decision-making and the implementation of planning.

“Public participation” may mean different things to different people [

19]. To the public, “public participation” means “public involvement.” Due to the differences in national systems and ideologies, public awareness in Chinese society is generally weak, and people lack awareness regarding their role as the subjects of social affairs. Public participation has become a top-down administrative behavior. Therefore, strictly speaking, public participation in China is symbolic and insufficient, where “public participation” is unlike that practiced in Western countries [

20]. For the government, “public participation” means “civic engagement.” The focus of public participation under the leadership of the government is to expand the breadth of participation, ensure the arrival of planning information to individuals, and increase the number of people involved. Additionally, the government focuses on expanding the depth of participation, ensuring the readability of planning information, and facilitating the reception of public information. This leads to a series of problems: the pursuit of increasing the number of participating individuals and display methods increases costs and reduces the implementation ability of participation, and the expansion of the participation base increases the degree of individual heterogeneity and subtly reduces the readability of planning information.

2.1.2. Public Participation in Urban Planning

Spatial planning is an elusive topic for planning professionals who understand specific procedures, and it is an even more vague topic for the general public, but decision-making needs to be understood and influenced by all stakeholders and their representatives [

21]. Public participation complicates urban planning and damages the autonomy and efficiency of planners to a certain extent, but extensive participation may lead to better planning [

22]. The rational basis of urban decision-making includes the role of individual free choice. The necessity of public participation in urban decision-making is uncontroversial; however, the process requires careful planning, adequate preparation, flexible responses to the influences of external factors, and active interaction between multiple parties [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Public participation in modern urban planning originated from the British planning system [

13]. The basic pattern of participatory planning became popular in the U.K. in the 1940s and 1950s [

26]. In 1947, the U.K. created the “Urban and Rural Planning Act” to encourage the public to express their personal opinions on urban development during the planning process, and created the conditions for the establishment and implementation of participatory planning patterns. The rise of public participation is the result of the renaissance of liberalism and the civil rights movement. The awakening of the public’s self-awareness put forward demands for individual rights in society. In 1969, Arnstein put forward a famous ladder theory for public participation problems in urban planning. The theory describes eight forms of public participation and attempts to establish a unified planning decision-making mechanism among stakeholders, such as governments, enterprises, communities, and non-profit organizations, such that public awareness can genuinely play a role in community planning [

27]. In the context of globalization, one may draw lessons from Habermas’s concept of communicative rationality and Giddens’s structural theory, where collaborative planning emphasizes the realization of common goals through the cooperation of stakeholders [

28]. The degree of a citizen’s public participation may be affected by their living environment, economic status, family, religion, etc. The participatory planning theory formed and developed in Western countries usually lacks consideration of the potential impacts in political, economic, and social contexts, and is not entirely applicable to developing countries [

8,

11,

26,

29]. Researchers need to discuss different cultural and institutional backgrounds and critically evaluate the planning practices used in Western countries, along with the resulting outcomes [

20].

In China, the people’s primary status in the process of public participation is determined by the public policy attributes of urban planning. On the one hand, as urban planning provides a physical public product, any individual might directly or indirectly become a user of that product; on the other hand, as a piece of intangible urban planning information, no matter how complicated the intermediates are in the process flow from the government to the public, the public is always the final receiver and sender of feedback information. Furthermore, the public’s dominant position in the process of public participation is protected by relevant laws. In 2008, the Urban and Rural Planning Law clarified the basic requirements for public participation in the urban and rural planning process, and the New Urbanization Planning (2014–2020) scheme has proposed methods for China’s future urban development thinking, which is centered on public participation.

2.2. Community Planning and Public Participation

2.2.1. Community Planning and Development in China

The essence of community planning is social planning, which means that through the scientific allocation and a reasonable layout of public resources, fairness regarding the interests of relevant individuals and groups in the development of the community can be realized. Western countries regard community planning as an extension of urban planning, taking blocks as a unit, and implementing social governance from the perspective of urban regeneration. After a long period of exploration, a high-quality development mechanism has gradually formed [

30].

Whether in developing or developed countries, urban regeneration has always been an eternal theme in the process of globalization and urbanization [

26,

31,

32]. Since the 21st century, with the development of the “Four Modernizations,” China’s population and economic drivers have gradually gathered in cities, and the scale and complexity of urban issues have further expanded. Determining how to coordinate the relationship between different stakeholders will become increasingly important in urban planning issues. As the basic urban management unit, the community is the best practical place to realize grassroots democracy. The quality of development will be the key to determining the success of China’s future social and economic transformations. China’s urban revival must scientifically manage the weak links between the multilevel planning process, meet the needs of local communities, and pay attention to the scalar politics of community-level planning and implementation [

16,

33].

In the planned economy era in China, with its highly concentrated power, communities have obvious unit attributes. In community planning, state and government regulation and control are dominant, and communities lack a general social foundation and the corresponding institutional support. With the transition from a planned economy to a market economy, the market forces have gradually penetrated the community level and have become involved in community planning as a new force. Under the influence of market forces that have maximized the development of entities’ interests, community planning has gradually appeared with various malpractices that harm public interests. Therefore, the state has passed legislation to clarify the role of the people during public participation. Nowadays, under the background of new urbanization policies, healthy, fair, and sustainable urban planning theory and community planning practices are becoming increasingly valued [

34]. Healthy community planning requires a breakthrough in traditional planning patterns, which involves focusing on creating a healthy community environment and equal chances for using community facilities by the public to improve the quality of life for residents [

35].

2.2.2. Public Participation in Community Planning

With the in-depth development of community governance, public participation in community planning has become more prominent, and participatory planning has become an essential part of community development [

36]. In developing countries, due to the generally low civic awareness, factors such as the individual growth environment, economic status, ethnicity, family, and beliefs significantly impact the degree of participation in community planning [

8].

Public participation in community planning originated in the United States. The mechanism of public participation in urban communities mainly includes three modes: “top-down,” “bottom-up,” and “hybrid.” Community participation in China is mainly combined, including the bottom-up and top-down modes, which is different from the practice of community participation in Western countries [

26]. The issue of public participation in urban regeneration is the focus of policymakers, scholars, and the public. Public participation is not a specific plan, but instead a part of urban regeneration, which is considered as the basis of successful community planning [

37]. The current urban planning practice in China shows an increasing demand for public participation and coordinated planning. Mobilized citizens and the central government indirectly form an alliance that effectively balances the pro-growth coalition between the local government and private enterprises, which helps the planning shift to a more inclusive governance method [

38]. The orderly participation of the public in community construction and management is undoubtedly a critical way to realize the stable development of communities. The different types of community planning (such as the community planning in China’s urban–rural fringe villages) should pay more attention to local managers and villagers (especially young people) and adopt a bottom-up approach to fully facilitate participation in community development [

39].

2.2.3. Multistakeholders’ Involvement Approaches and Methods

Multistakeholder involvement has increasingly drawn attention in urban planning to overcome the communication obstacles, such as lack of smooth information flow and asymmetric rights of different groups [

40] (Steiner & Markantoni, 2014). The multistakeholder involvement is full of uncertainty and contradiction, which often entails a process of “muddling through” [

41,

42] (Lindblom 1959; Sayer et al., 2008). Efforts have been made to enhance multi-stakeholder involvement and public awareness for involvement [

43] (Adekola et al., 2020). Multistakeholder involvement platforms are one of the approaches to strengthening institutional coordination, enabling discussions, negotiations, and joint planning between stakeholders from various sectors [

44] (Kusters et al., 2018), balancing the various interests [

45] (Zagt & Chavez-Tafur, 2014). Participatory action-oriented research is a ”philosophical” approach to recognizing the persons who need to participate in community development and the factors that affect them [

46] (Vollman, Anderson, & McFarlane, 2004). This approach’s key elements are interaction, multi-actors, and multilevel perspectives in the joint involvement of the supply side (social professionals, policy implementers, policymakers) and the demand side (vulnerable groups), which achieve the connection between different groups through dialogue and interaction. Partnership research highlights three issues: the reach, the depth of participation, and the power dynamics between stakeholders [

47] (Numans et al., 2019). The decision support platform enables the multistakeholders to communicate and understand the issues to be placed on the table for discussion [

48] (Ramsey, 2008; Hill et al., 2019).

3. Analytical Framework

3.1. Determining a Reasonable Public Participation Unit

3.1.1. Social Class and Public Participants

The current general public participation pattern ignores the differences between participants and units or one-sidedly regards an individual as the basic unit of public participation. Therefore, most of the public participation in various urban planning stages under the government’s leadership directly points to civic engagement and lacks significant intermediate links. The essence of this is that the participation process lacks a reasonable participation unit, which is the fundamental reason for the inadaptability of Chinese public participation.

With China’s economic development and social changes, the public’s values have become increasingly diverse, and public differences have gradually increased. Public differences are manifested in the differentiation of social classes at the macrolevel and gradually form a new social class differentiation mechanism based on occupations. Chinese society can be roughly divided into ten classes, and the economic resources, cultural resources, and social relations held by each class are quite different. “Civic engagement” is the main body of urban planning, and all classes have the fundamental right to join in public participation, but only the middle and upper classes can make a real impact in social development and government decision-making. After agricultural laborers (a class less likely to participate in urban planning) are excluded, the number of groups that can make an impact decreases further. Comprehensive and complete public participation requires that the public can genuinely participate in the planning decision-making process [

27]. The diversified urban planning ideas proposed by Paul Davidoff inspired a generation of young planners to speak on behalf of disadvantaged groups, which became a sign of the transformation of urban planning to include public participation in Western countries [

49,

50]. The city of Seoul in South Korea has adopted the pattern of citizens directly participating in basic urban planning formulations, in which citizens directly participate in the planning process, have a more extraordinary voice and decision-making power, and formulate relevant urban planning based on input from all social strata [

51].

It is challenging to conduct a comprehensive analysis of individuals in the context of a pluralistic society, and there are also problems relating to differences in the ability to participate in public affairs between individuals. Simultaneously, when considering lower social classes, the difference in their initiative to participate in social affairs gradually becomes greater, and their participation in urban planning is more limited to the types of planning that have a direct relationship with their location or interests. This is also the reason for the relatively high public participation enthusiasm in community planning. By reducing the spatial scope of planning work, the public’s sense of ownership in planning can be enhanced and enthusiasm for participation will increase [

52].

3.1.2. Social Groups and Public Participation Units

Sociology regards the people as the main body of social development, and specific groups as the basic units of social analysis. Society is not a group of people with a single culture and a single set of values. Instead, people of all classes, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds can form interest groups. Every social group can be defined by a shared sense of identity [

53], where individuals share a sense of unity and share common goals and expectations. Groups under the same circumstances will take the same or similar actions, make similar choices regarding policies in the name of common interests, and play a role in promoting fairer urban development [

54,

55,

56].

Chinese family relationship theory categorizes social relationships based on the “five relationships”: blood relationships, i.e., clan relationships formed by direct and collateral blood ties, including parents and children; marriage relationships, i.e., kinship based on marriage, including husband and wife relatives; geographical relationships, i.e., special close relationships triggered by neighboring geographical space, such as relationships with neighbors and fellow towns; business relationships, i.e., special close relationships triggered by past or existing occupational reasons, including colleagues, teachers, and students, etc.; emotional relationships, i.e., special close relationships between people that are triggered by absolute chance, like a Taoist friend. Among the five relationships, blood relationships are the core and foundation of all social relationships, and the other four relationships are extensions and generalizations of blood relationships. From blood relationships to emotional relationships, the intimacy of the five relationship types gradually weakens, where hierarchical relationships are gradually increased and the force of this phenomenon is gradually increased as well.

The above five types of relationships divide society into five groups in the order of blood relatives, in-laws, community organizations, industry associations, and intermediary organizations. Equal relationships between individuals and groups are the key to ensuring the effective operation of modern society. Based on this, the five groups can be divided into two categories: First, the family, where clan relationships based on blood and in-law relations have a clear hierarchy of internal members, and the rights of senior individuals (elders) are supreme; elders often become group spokespersons, and internal relationships cannot achieve complete equality. Second, civil society. Civil society, as an organization in the field of social life, is voluntary and spontaneous [

57]; it includes community organizations formed by geographic relationships, industry associations (commercial unions and labor organizations) formed by industry relationships by linked businesses, and intermediary organizations (non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and non-profit organizations (NPOs)) formed by emotional relationships. Their internal members have close and equal relationships. A vibrant civil society may play a more critical role in consolidating and maintaining democracy than initiating democracy [

58]. Civil society is strengthened through its organizations’ activities that encourage broader citizen participation [

57].

The above five groups can all constitute a basic unit of public participation. The key to ensuring the smooth progress of public participation in urban planning is to analyze the differences between groups, study their organizational forms and operating mechanisms, determine a reasonable participation unit for a specific planning type or planning stage, and seek to maximize the degree of consistency between all parties’ interests.

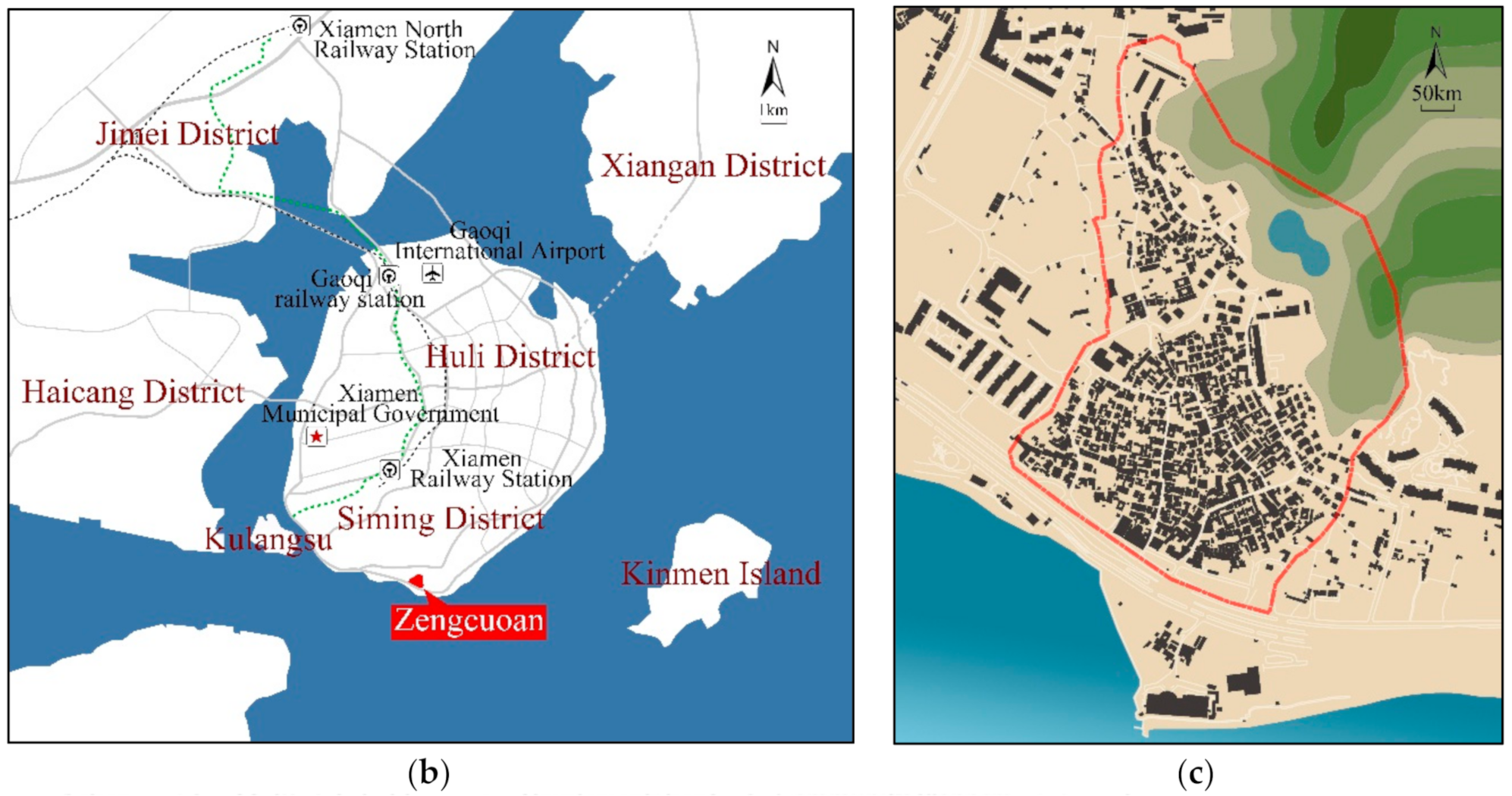

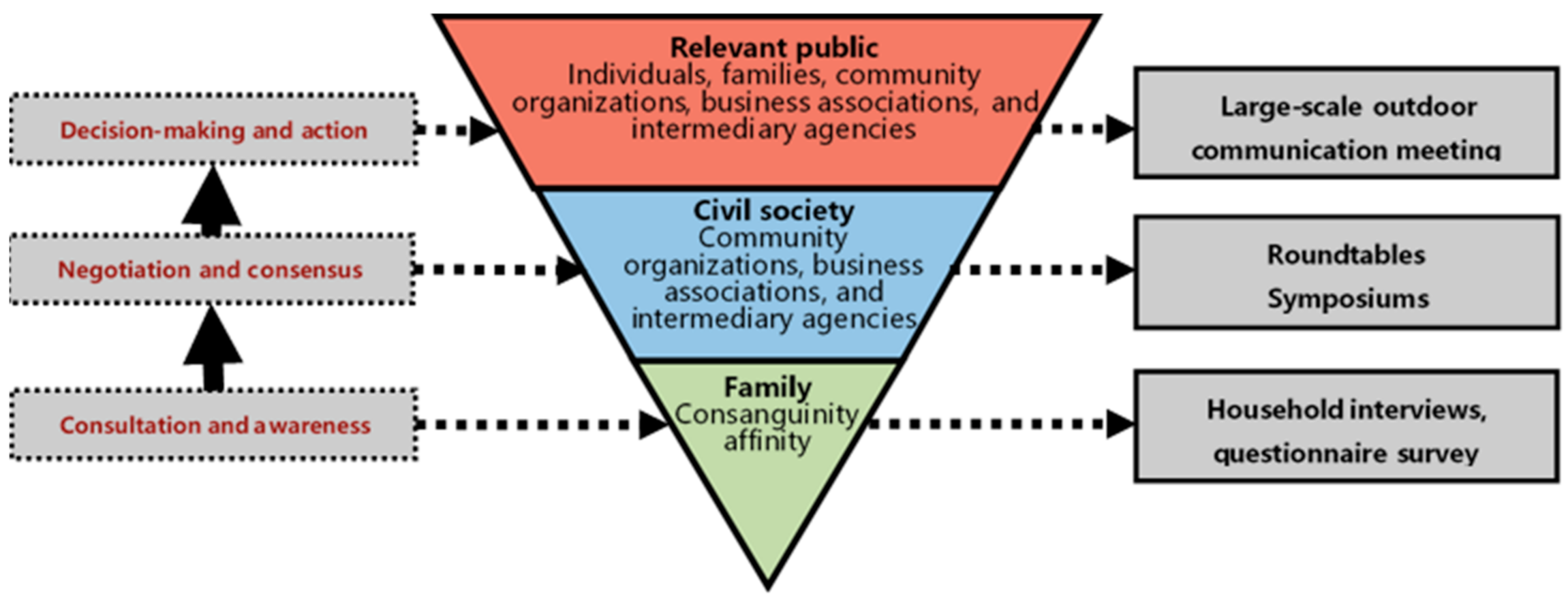

Figure 1 summarizes the methodological framework of this study, which explains the methods, stakeholders, and working stages.

3.2. Recognition of Public Participation in Community Planning

3.2.1. The Complexity of Public Participation in Community Planning

In modern society, the community is not only a material carrier for shaping the image of a city, but is also a basic unit for solving urban problems; community planning is no longer a top-down expression of the will of the elite, but is instead the practice of bottom-up public interest maintenance. A government’s cooperation and coordinated promotion are essential factors that cannot be ignored in community planning. The combination of public participation and community planning has a strong endogenous motivation from beginning to end, which is the appeal of community governance; it also carries a reflection of the traditional way of resource allocation, that is, the bottom-up reaction to “top-level design”. Public participation in community planning plays a vital role in promoting the community’s comprehensive governance and overall development.

The diversity of communities and the comprehensiveness of community planning determines the complexity of public participation: First, the dominant position of the differentiated “public” in community planning must be clarified. The composition of modern communities is comprehensive. Take a residential community as an example, where its members include residents, management service providers, and community organizations. Particular types of communities also include related practitioners and foreign tourists. The preparation of community planning aims to satisfy the majority of members’ collective demands and realize the public’s dominant status based on the contradictions of individual differences and collective actions. Second, the operating mechanism of community planning determines the diversity of public participation subjects. Community planning is generally divided into three stages: pre-analysis, mid-term preparation, and post-implementation, which correspond to the expression and confirmation of the individual community interests; the evaluation and balance between individual community interests; the long-term layout of community development, adjustment, and the implementation of corresponding interest relationships; and the process of information feedback, respectively. The difference in the content of each stage of community planning determines the different participants, which is specifically manifested in the progress from analysis and preparation to implementation, where the number of core participants gradually decreases and the group levels gradually increase.

3.2.2. The Importance of Social Capital in Community Planning and Public Participation

The social groups participating in community planning do not exist in isolation but are instead interconnected network systems, which are called “social capital.” Social capital refers to the interacting organizations, interactions, and beliefs that affect society in terms of quantity and quality [

59]. Social capital is not a simple addition of social institutions, but is instead the “glue” that consolidates social institutions to establish trust and reciprocal relationships within and between the main stakeholder groups [

60]. In a democratic society, action groups undertake specific social tasks and build a substantial organizational network to form social capital. The social network, as a core component of social capital, enhances the sufficient supply of public social products through enhancing the willingness and ability of citizens to participate in public affairs [

61]. Different groups are managed through the dialogue of internal members and fight against the dominant external forces on this basis, while the public participates in the decision-making process of urban planning in the form of “groups”. Social capital plays an essential role in the formulation and implementation of community planning. Cultivating civil society and improving social capital is the focus of public participation in China’s community planning at this stage.

4. Micro-Regeneration of the Zengcuoan Community in Xiamen

4.1. Background of the Study Area

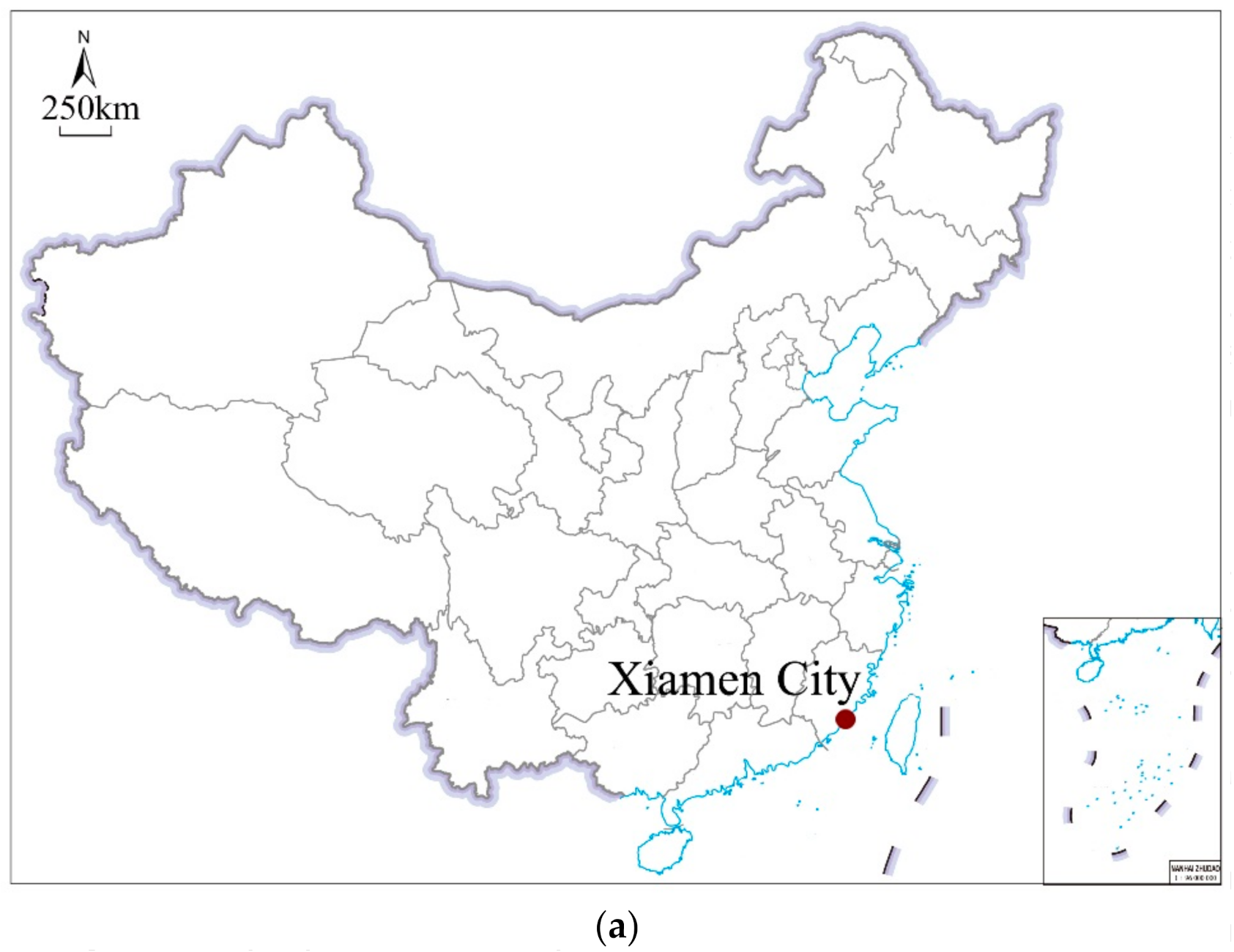

Xiamen is located in the southeast of Fujian Province in eastern China. It is a special economic zone approved by the State Council and an important central city and scenic tourist city on the southeast coast (

Figure 2a). Zengcuoan is located in the southern part of Xiamen Island, found along Binhai Street, Siming District, with an area of approximately 6.5 km

2; the current registered population is 4252 and the temporary resident population is 5929. The village is located 15.5 km from Gaoqi Airport, 29.7 km from Xiamen North Railway Station, 11.9 km from Gaoqi Railway Station, and 6.8 km from Xiamen Railway Station; as such, its location has obvious advantages (

Figure 2b). Zengcuoan is surrounded by mountains on three sides and sea on the other side. The buildings on the mountains are scattered and the landscape is unique. It attracts a large number of tourists every year (

Figure 2c).

From a small fishing village near the sea to a tourist destination sought after by literary youths, the development of Zengcuoan has gone through four main stages, specifically, the traditional fishing village stage before the 1990s, the initial stage of development after the 1990s, the formation stage of the cultural and creative fishing village at the beginning of the 21st century, and the coexistence stage of prosperity and poverty since 2012. The current residents of the Zengcuoan community are mainly outsiders that are generally engaged in tourism-related industries, such as inn management, catering services, and souvenir sales. Approximately 80% of community houses are inns, most of which are leased to outside tourism practitioners by community residents. These types of inns have a good construction quality and sense of design. There are already fewer than 500 aboriginal people living in the community. After renting their houses to operators, most residents choose to rent houses in surrounding villages to make use of the difference in the price of rent.

With the rapid development of Xiamen’s tourism industry, Zengcuoan has attracted more outside tourists. The rapid development of tourism-related industries, such as accommodation and catering, has also brought specific community governance problems. On the one hand, community development has become disorderly, street spaces have been destroyed, building facades are messy, and the public space is seriously insufficient. On the other hand, the industrial threshold of Zengcuoan has been set too low, mobile stalls such as barbecue and fruit stalls continue to occupy street space, and problems such as the dirty environment and noise pollution have become more common. Simultaneously, due to the long creative cycle and low operating profits of the cultural and creative industries there, some businesses have moved out, because they cannot bear the pressure of rising rents.

4.2. Development Dilemmas and Countermeasures for the Zengcuoan Community

After a period of rapid development, Zengcuoan has become a literary and artistic village that integrates cultural creation, music, homestays, and catering. The village is favored by young people, earning the reputation of “China’s most literary and artistic” fishing village. However, with the rapid development of the community, Zengcuoan’s future is also facing new challenges: To maximize the benefits of the land, expanding and rushed construction has prevailed. Excessive commercialization has eroded the original literary atmosphere, and the current development path is unsustainable. The prosperity of the tourism industry hides the decline of the traditional fishing village culture.

Residents and businesses have realized that the future development of Zengcuoan is closely related to their interests. A good spatial environment is an essential foundation for ensuring healthy and livable communities and the sustainable development of the tourism industry. Therefore, the aboriginal and outside operators of Zengcuoan are eager to improve the physical environment, enhance the overall quality of life, and create a good tourism atmosphere. Against this background, since 2014, Sun Yat-sen University has taken the lead and engaged with the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Taiwan’s Feng Chia University, Xiamen University, and other institutions to form a “collaborative workshop” that carries out micro-modification planning for the tourism (Zengcuoan), old town (Lujiang sub-district), and rural areas (Yuanqianshe Village), including other different types of communities in Xiamen. The collaborative workshop takes the community as the basic unit, with the participation of the masses as the core, and focuses on the construction and development issues, starting with the innovation of the spatial environment and governance mechanisms, guiding multiple subjects to participate in a collective investigation and analysis. Additionally, the workshop focuses on the preparation and implementation of multistage planning practices and collaboration to form a beautiful environment and a harmonious society together.

4.3. New Ideas for Public Participation under the Collaborative Pattern

4.3.1. System Construction throughout the Process

In 2013, the “Beautiful Xiamen Strategic Plan” put forward the developmental concept of “creating a beautiful environment together”, with public participation as the core concept, and “co-planning, co-construction, co-management, co-evaluation, and sharing” as the path to success that identifies the direction for community construction in Xiamen.

Public participation in community renovation via collaboration is no longer limited to the planning and implementation links but includes the whole process of system construction. First of all, the government conducts extensive publicity events that explain the basic concept of collaboration to create a social atmosphere for it, organizing the establishment of a collaborative workshop, drawing up plans for the renovation of various districts, coordinating funding arrangements, and coordinating related work. Second, a community construction and management platform has been built in which multiple subjects participate together based on the pattern of collaborative workshops. The workshop’s workflow includes three stages: preparation for new construction, launching themed activities, and building beautiful homes together (

Figure 3). Third, relevant community management and autonomous organizations have been established to strengthen their essential role in planning implementation and community management. Zengcuoan has established branches, such as the Homeowner Association, Cultural and Creative Council, and Dispute Resolution Center, under the Public Discussion Council framework.

4.3.2. The Inverted Pyramid Structure of the Public Participation Unit

Public participation under the collaborative workshop pattern includes three stages: consultation and awareness, negotiation and consensus, and decision-making and action. Each stage has different participation units and working methods (

Figure 4). First of all, the consultation and cognition stage’s main tasks are household interviews and questionnaire surveys. The completeness and authenticity of the collected information are ensured by entering the households one by one in each area. Every community member has an equal opportunity to express their views regarding the development of the community. Second, the main methods of the consultation and consensus phase are roundtables and symposiums. At this stage, the Zengcuoan collaborative workshop organized a roundtable meeting attended by diverse community stakeholders. Based on the preliminary research results, the participants were guided to speak freely, and then the feedback information was screened and sorted to form a preliminary plan. Businesses, community organizations, and professionals took part in the program seminars, in which all stakeholders discussed how to solve practical community development problems based on their interests and collaboratively formulated community development contracts. Third, the primary method of the decision-making and action stage is a large-scale outdoor communication meeting. This is in the form of being fully open to the public, showing work results, collecting comments on revisions, strengthening the public’s understanding and recognition of the plan, and promoting the implementation of the plan. The three stages of the public participation units of the inverted pyramid structure ensure the community’s primary status in the public participation process. Simultaneously, the selection of different participants for different stages helps to achieve a balance between the breadth and depth of public participation, to grasp the principal contradictions, and to improve work efficiency (

Figure 5).

4.3.3. The Multiple Identities of the Participating Members of Community Organizations

The civil society, composed of community organizations, industry associations, and intermediary organizations, is the core force in the community renovation plan’s implementation stage. In modern society, citizens’ identities are non-unique. Community residents participate in multiple community organizations as individuals, forming a diverse and complex social capital network within the community. Community organizations operate independently through their engagement mechanisms, interoperating based on members’ identities, and jointly exercising community management rights. In the Zengcuoan renovation plan’s implementation stage, people spontaneously promoted the renovation and upgrading of the surrounding space based on their identities. For example, after extensively soliciting opinions from relevant interest groups, the operator of the Dora Inn surnamed Wu (the business representative who participated in the public participation in the planning stage) transformed the surrounding idle land into a public space with fishing boats as the theme, which was recognized by many parties. Dora Inn is located at 478 Wenqing Street, Zengcuoan. It is adjacent to the same unused land as lot 470, Chengguo Inn, which is used for stacking construction waste and scattered vegetable cultivation. Wu contacted the operators of Chengguo Inn and the owners of lots 478 and 470, negotiated and collaborated on a project, and proposed a plan for the renovation of unused land based on the opinions of the public and designers. The plan was to transform the land into a street park with a fishing boat theme. Dora Inn was responsible for the overall renovation, upgrade, and daily management of the park; the two inns were responsible for the implementation of transforming their walls into green hedges and the daily maintenance required (

Figure 6).

Furthermore, the collaborative workshop combined registration and recommendation through teaching planning skills to establish a “community planner” organization composed of residents, businesses, literate youths, artistic youths, and community compatriots from Taiwan. The community planner’s multiple identities played a critical leading role in designing the tourism identification system led by the organization and the transformation of the Caifu ancestral home of Kinmen into a fishing village cultural center.

5. Discussion

Unlike Western countries, due to weak civic awareness and low self-government capabilities, most community planning in China has adopted a government-led, top-down approach. While the public’s status as the main body of public participation has been established, the problem of elucidating how to reasonably determine the basic unit of public participation has not attracted attention for a long time. With the transformation of community governance logic and the advancement of community construction work, it is vital to explore new participatory community planning methods that combine government guidance and spontaneous citizen leadership and consider both top-down and bottom-up modes simultaneously.

The case of the micro-renovation of the Zengcuoan community in Xiamen shows that, on the one hand, in China, the role of government departments in participatory community planning is irreplaceable. It plays an important role in the pre-publicity, the form of the working platform, the community management, and the cultivation of autonomous organizations. On the other hand, in the specific process of public participation, for the three different stages of consultation and awareness, negotiation and consensus, and decision-making and action, it is necessary to determine a reasonable participation unit and choose a scientific working method. The three-stage public participation unit proposed here is composed of an inverted pyramid. While ensuring the people’s status as the main body of public participation, the differentiated selection of participants helps to achieve a balance between the varying breadths and depths of public participation.

The collaborative workshop mentioned here was led by relevant government departments or autonomous social organizations. It adopted flexible and diverse working methods to mobilize and organize residents and community organizations to participate in community construction and governance in response to the problems and needs that arose regarding community construction and development. The collaboration’s core purpose was to communicate the relationship between government administrative actions and citizens’ spontaneous behavior, starting with specific projects, such as space and building renovations, and providing community residents and community organizations an opportunity to participate in community development decision-making and community management affairs. The government, community residents, community organizations, and other stakeholders reached a consensus through communication and consultation, where fairness regarding the interests of relevant individuals and groups in the community development was realized through the scientific allocation and reasonable layout of public resources. With the progress of rapid urbanization, increasingly more Chinese communities are facing conflicts between cultural remodeling with space renovation and environmental protection with development and construction. The collaborative workshop here took the community as a unit and public participation as the core, and by starting from the need for a spatial environment transformation and a governance mechanism innovation, guided multiple subjects to participate in the investigation and analysis, as well as the preparation and implementation of multi-stage planning practices to produce a better environment and a harmonious society. In March 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development issued their “Guiding Opinions on Carrying out Activities for the Joint Creation of a Beautiful Environment and a Happy Life in the Construction and Improvement of Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environments” scheme, which affirmed the collaborative practices of Fujian and Guangdong and proposed a long-term mechanism for collaboration in urban and rural communities.

6. Conclusions

With the continuous development of social governance research and practice, the role of public participation in community planning has received increasing attention. Simultaneously, in some developing countries, public participation models from Western countries have shown a certain degree of inadaptability. On the one hand, in China, the public policy attributes of urban planning determine the people’s subject status in the process of public participation, and their subject status is protected by the “Urban and Rural Planning Law” and other relevant laws. On the other hand, the general mode of public participation in China ignores the differences between the participants and the participating units. Most of the public participation in various urban planning stages under the government’s leadership is directly aimed at the public and lacks significant intermediate groups. The essence of this issue is the lack of a reasonable participation unit, which is a fundamental reason for the inadaptability of public participation shown in China.

This study used Zengcuoan in Xiamen as an example to introduce the development and practice of a collaborative workshop pattern in China’s participatory community planning. This study analyzed how to establish a public participation system covering the entire process of preparation, concentrated work, and follow-up, as well as a series of issues on how to determine public participation units and public participation methods regarding the consultation and understanding, negotiation and consensus, and decision-making and action stages. Research has shown that traditional government-led work methods are no longer appropriate for the new problems and situations that China faces regarding community governance and construction. Exploration of collaborative patterns when selecting participating units and the design of participation schemes, as well as the role of community organizations, has particular reference value for public participation in current urban planning in China. Furthermore, it provides community governance and community construction lessons for other developing countries.

The changing roles of the government and planners, as well as the functions of community organizations, play a catalytic role in participatory community planning. China is different from Western countries, where, although the previously used government-led community governance methods have changed, government departments have still done much of the work in community planning and public participation in terms of the preliminary publicity and work platform construction. Under the collaborative workshop pattern, community planners have specific professional skills and are not attached to any government department, which helps them to eliminate the gap between the government and citizens in public participation and connect the government, community residents, and community organizations, forming a dialogue platform for other stakeholders. Additionally, community residents participate in multiple community organizations as individuals, realizing communication based on the identities of members and jointly exercising community management rights through spontaneously promoting community construction.

With the development of community governance mechanisms and community construction practices, the subjects of public participation in community planning have become increasingly diversified. In-depth cooperation between the government, community planners, and community organizations has become an important force in maintaining community health and sustainable development. Elucidating how to improve the legal status of public participation in urban planning systems and determining how to regulate the work content and behavioral norms of different participants in participatory community planning will be the critical content of further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and W.L.; methodology, Y.H.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.C.; supervision, W.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China, grant number 2018A0303130087, and the Soft Science Research Program of Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China, grant number 2020A1010020014.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the two anonymous reviewers who have provided valuable comments in revising this manuscript. We shall extend our thanks to Xun Li for all his kindness and help. We would also like to thank the colleagues, Jinmiao Zhou, Tingitng Chen, and Fan Zhang, who have participated in this project. Last but not least, I’d like to thank all my friends, especially my three lovely roommates, for their encouragement and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gillette, H., Jr. The evolution of neighborhood planning: From the progressive era to the 1949 housing act. J. Urban Hist. 1983, 9, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M. From Local to Global: One Hundred Years of Neighborhood Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formations. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1996, 23, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Speculative urbanism and the making of university towns in China: A case of Guangzhou University Town. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagoe, C. One tool amongst many: Considering the political potential of neighbourhood planning for the greater carpenters neighbourhood, London. Archit. MPS 2016, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Biondi, L.; Demartini, P.; Marchegiani, L.; Marchiori, M.; Piber, M. Understanding orchestrated participatory cultural initiatives: Mapping the dynamics of governance and participation. Cites 2020, 96, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J. Public Participation in Urban Development the European Experience; Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 1995; pp. 396–398. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, H.S. Ethical behavior is extraordinary behavior; It’s the same as all other behavior: A case study in community planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1998, 64, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Lynn, T.; Wargent, M. Contestation and conservatism in neighbourhood planning in England: Reconciling agonism and collaboration? Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yung, E.; Chan, E. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choguill, M.B.G. A ladder of community participation for underdeveloped countries. Habitat Int. 1996, 20, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L. Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: How to achieve sustainable hazard mitigation. Nat. Hazards 2003, 28, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. Urban Planning Theory Since 1945; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, B.; Ng, M.K. Urban regeneration and social capital in China: A case study of the drum tower muslim district in Xi’an. Cities 2013, 35, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing neighbourhood cohesion under the impact of urban redevelopment: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X. Urban redevelopment as multi-scalar planning and contestation: The case of Enning Road project in Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Jenkins, V. Planning and Nuisance: Revisiting the Balance of Public and Private Interests in Land-Use Development. J. Environ. Law 2011, 23, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1973, 4, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- John, F. Planning in the Face of Power. J. Politics 1982, 48, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; de Roo, G.; Lu, B. ‘Communicative turn’ in Chinese spatial planning? Exploring possibilities in Chinese contexts. Cities 2013, 35, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, S. Public Participation in Spatial Planning Procedures. Comparative Study of Six EU Member States. Justice and Environment. 2013. Available online: http://zagovorniki-okolja.si/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Land-use-planning-and-access.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2015).

- Carp, J. Wit, style, and substance: How planners shape public participation. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 23, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotchie, J.F. The individual, the community, and the authority in the planning process. Environ. Plan. A 1979, 11, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosener, J. Matching Method to Purpose: The Challenges of Planning Citizen-Participation Activities. In Citizen Participation in America: Essays on the State of the Art; Langton, S., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O.; Webler, T.; Rakel, H.; Dienel, P.; Johnson, B. Public participation in decision making: A three-step procedure. Policy Sci. 1993, 26, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative planning in perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.S. Urban regeneration’s poisoned chalice: Is there an impasse in (community) participation-based policy? Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, V.; Massengale, J. Street Design: The Secret to Great Cities and Towns; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J. The Elusive City: Five Centuries of Design, Ambition and Miscalculation; Herbert Press: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the “three old renewals” in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. Reconstructing scale: Towards a new scalar politics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 35, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Li, X. Exploring the Impact of Urban Green Space on Residents’ Health in Guangzhou, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05019022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hui, E.C.; Lang, W.; Tao, L. People, recreational facility and physical activity: New-type urbanization planning for the healthy communities in China. Habitat Int. 2016, 58, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.L. Involving Citizens in Community Decision Making: A Guidebook; Program for Community Problem Solving: Washington DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Newman, G.; Jiang, B. Urban regeneration: Community engagement process for vacant land in declining cities. Cities 2020, 102, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Tochen, R.M. Shifts in governance modes in urban redevelopment: A case study of Beijing’s Jiuxianqiao Area. Cities 2016, 53, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Markantoni, M. Unpacking community resilience through Capacity for Change. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.E. The science of muddling through. Public Adm. Rev. 1959, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.A.; Bull, G.; Elliott, C. Mediating forest transitions: “Grand design” or “muddling through”. Conserv. Soc. 2008, 6, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekola, J.; Fischabcher-Smith, D.; Fischabcher-Smith, M. Inherent complexities of a multi-stakeholder approach to building community resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, K.; Buck, L.; de Graaf, M.; Minang, P.; van Oosten, C.; Zagt, R. Participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation of multi-stakeholder platforms in integrated landscape initiatives. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagt, R.J.; Chavez-Tafur, J. Towards Productive Landscapes—A Synthesis. In Towards Productive Landscapes; Chavez-Tafur, J., Zagt, R.J., Eds.; Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vollman, A.R.; Anderson, E.T.; McFarlane, J. Canadian Community as Partner; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Numans, W.; Van Regenmortel, T.; Schalk, R. Partnership Research: A Pathway to Realize Multistakeholder Participation. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919884149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Kolmes, S.; Humphreys, M.; McLain, R.; Jones, E.T. Using decision support tools in multistakeholder environmental planning: Restorative justice and subbasin planning in the Columbia River Basin. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2019, 9, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.V. Paul Davidoff and Planning Education: A Study of the Origin of the Urban Planning Program at Hunter College. J. Plan. Hist. 2012, 11, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angotti, T. New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Municipal Government. Basic Urban Planning for Seoul 2030. 2013. Available online: https://seoulsolution.kr/sites/default/files/policy/1%EA%B6%8C_11_Urban%20Planning_2030%20Seoul%20Plan.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2015).

- Levinson, D. Network Structure and City Size. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J. The Rise and Fall of Self-Interest in the Explanation of Political Life. In Beyond Self-Interest; Mansbridge, J., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler, A.A. Community Control; Pagasus: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. The just city. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C. NGOs, civil society and democratization: A critical review of the literature. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2002, 2, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L. Rethinking civil society: Toward democratic consolidation. J. Democr. 1994, 5, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hui, E.C.; Zhou, J.; Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. Rural revitalization in China: Land use optimization through the practice of place-making. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, L.; Chowdhury, R.R. Tracing social capital: How stakeholder group interactions shape agricultural water quality restoration in the Florida Everglades. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebvises, P. Social capital, citizen participation in public administration, and public sector performance in Thailand. World Dev. 2018, 109, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).