Abstract

Cities face many challenges in their efforts to create more sustainable and resilient urban environments for their residents. Among these challenges is the structure of city administrations themselves. Partnerships between cities and universities are one way that cities can address some of the internal structural barriers to transformation. However, city–university partnerships do not necessarily generate transformative outcomes, and relationships between cities and universities are complicated by history, politics, and the structures the partnerships are attempting to overcome. In this paper, focus groups and trial evaluations from five city–university partnerships in three countries are used to develop a formative evaluation tool for city–university partnerships working on challenges of urban sustainability and resilience. The result is an evaluative tool that can be used in real-time by city–university partnerships in various stages of maturity to inform and improve collaborative efforts. The paper concludes with recommendations for creating partnerships between cities and universities capable of contributing to long-term sustainability transformations in cities.

Keywords:

sustainability; resilience; partnerships; collaboration; transformative; transition; city; university 1. Introduction

The future of global sustainability and the future of cities are tightly connected. Cities are home to more than half of the world’s population and must play a critical role in mitigating climate change and adapting to its impacts to allow residents to thrive. In fact, one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) specifically mentions the role of cities and urban areas, and the need for urban sustainability transformation, and several others focus heavily on cities [1]. Cities currently emit over 70% of all global carbon dioxide emissions [2]. Therefore, establishing and maintaining tight urban carbon budgets is key to meeting emissions and warming goals set out by the Paris agreement, the International Panel and Climate Change (IPCC), and UN Sustainable Development Goals [3]. Cities are increasingly feeling the effects of extreme weather and are particularly vulnerable because of their frequent proximity to coasts, floodplains, and dry areas. For instance, extreme wildfires have become a global phenomenon and cities from California to Australia are facing compounding struggles from the fires that seem to worsen every year [3,4,5,6]. In the 2019–2020 fire season, megafires burned across Australia, scorching over 25 million acres of land, killing roughly a billion animals, and destroying nearly 2000 homes. In California’s 2018 fire season, there were over 58,000 wildfires, with the Paradise fire incinerating an entire town and killing 85 people. In 2019, utility companies throughout California chose to preemptively shut off electricity for over 500,000 residents for fear of similarly devastating fires. This urgency is echoed in calls to focus sustainability research and practice on the sustainability transformation of cities and regions [7].

Sustainability problems such as climate change are complex and require innovative systemic solutions that span disciplines and institutions and are often slow to manifest [8]. These complex problems require transformation, or “radical, systemic shifts in values and beliefs, patterns of social behavior, and multilevel governance and management regimes” [9]. Municipal governments are attempting to mitigate and prepare for complex climate and energy challenges by creating sustainability and resilience agendas, which typically take the form of planning documents, civic mandates, and associated policy and programmatic actions [10]. Local governments, including municipalities, counties and regions, are primarily responsible for addressing climate change impacts, decarbonizing transit systems, transitioning to renewable energy, ensuring food access, and building more resilient and sustainable communities. However, they are often limited by institutional design, organizational logic, limited cross-jurisdictional coordination, and a general lack of skill and capacity for dealing with the uncertain and fast-changing nature of sustainability and resilience challenges [10,11]. Municipal plans and policy initiatives necessitate and often explicitly call for cross-sectoral and inter-institutional partnerships and collaborations (i.e., between cities, businesses, universities, NGOs, and community organizations) that can help dismantle institutional barriers and path-dependencies so that more innovative and holistic solutions can be achieved [12]. For instance, in an analysis of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities strategy documents, partnerships and collaborations were the most commonly cited planning, development, and implementation strategy across US cities [13]. Additionally, partnerships and collaborations with other institutions, like universities, have become increasingly important because they can help cities and other municipal governments address complex challenges, develop innovative solutions by operating across departments and jurisdictions and build capacity for sustainability problem solving.

Sustainability science and related fields (e.g., climate science, environmental science) continue to call for greater transdisciplinarity and applied research to increase the rate and real-world impact of discovery for urban sustainability and resilience [10,13]. A 2018 Nature article recognized the urgent need for research on the intersection of cities and climate change [3]. The article, and a subsequent publication from the National Science Foundation (NSF), called for increased understanding of “sustainable urban systems science”, and deeper partnership between researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to co-create knowledge and solutions together [14]. This research underscores the need for collaboration that supports innovation and transformation at the local level that can be shared and scaled globally.

City–university partnerships (CUPs) are emerging as mechanisms for the development, implementation and assessment of sustainability and resilience measures—creating the environment for sustainability science research to be more tightly coupled with sustainability problem-solving by urban policymakers [15,16]. Universities are particularly well suited to advance sustainability research and practices, especially at the local level, due to their position as “anchor institutions” or place-based organizations with a deep connection to the local community [17,18]. When universities and cities partner, there is an increased ability to build a transformative innovation ecosystem, where new ideas and solutions can be co-created, applied, and adopted for immediate impact [18,19,20].

Across the world, increasing numbers of CUPs are forming to support a range of climate change and sustainability-oriented work. For example, in the US, Smart City San Diego is a partnership between a university, municipality, utility company, and non-profit organization aimed at accelerating a regional transition to a green economy [15]. The Sustain-Lite project is a partnership in Singapore between a university, the local government, and a private business, responding to predicted growth of trade and commerce in Asia, and developing knowledge and tools for supply chain innovation [15]. Keeler and colleagues (2016) describe utilizing city–university partnerships across North America, Europe, and Asia to transfer and scale solutions to sustainability problems [21]. CUPs are rapidly developing at a global scale. For instance, the Educational Partnerships for Innovation in Communities–Network (EPIC-N), which unites local governments and communities with universities, now has 37 members spanning four continents, nine countries, and continues to grow [22].

While CUPs have structural similarities, e.g., they all include some form of agreement between researchers or administrators from universities and city administrators to formally collaborate, the partnerships operate in different modes. CUPs established to address complex sustainability problems such as climate change can be understood as falling into one of three modes: routine, strategic, or transformative, summarized in Table 1 [23,24]. Routine partnerships are transactional and consultant-based; limited joint efforts that are suited for static and straight-forward problems (e.g., the City of Portland and Portland State University working together to develop a map of street trees) [13,25]. Strategic partnerships focus on co-creation with both the city and university partners contributing to the goals and design of the collaboration. Such partnerships are often addressing more complicated problems that are value-laden and have multiple solutions (e.g., Tempe, Arizona working with ASU to design and implement a process to create a climate action plan). Transformative partnerships are formalized, with deep cross-institutional learning and mission alignment; these are well-suited for complex or wicked problems that include long-term goal setting, contested solution spaces and regular evaluation and updating of developed solutions (e.g., the holistic partnership between the University of British Columbia and the city of Vancouver working to accelerate and navigate urban sustainability transitions) [25,26,27,28]. There is an increasing need for these kinds of transformative partnerships given the growing awareness and pressure to make progress on complex issues [29]. Understanding which partnership mode a CUP is operating within lays the foundation for evaluating a CUP for, among other things, coherence between partnership goals and partnership structure.

Table 1.

This table shows three types of partnership structures, their attributes, and the context in which they are most applicable.

Developing effective monitoring and evaluation (M&E) techniques for all modes of CUPs is a vital component for intervention implementation, management, learning, and adjustment; for transformative CUPs, it is imperative. Iterative M&E of interventions provides real-world decision-making strategies for administrators, while also delivering comparable data for long-term research and analysis [30,31]. Appropriate development and implementation of CUP specific M&E tools can fulfil the real need to assess new and ongoing efforts and offer recommendations for improvement.

The partnership evaluation literature across several fields of study provides some common indicators for successful partnerships and collaborations. However, there is little guidance regarding specific strategies for CUPs seeking transformative sustainability and resilience outcomes. In general, partnerships and collaborations tend to be assessed based on: trust and trust-building; understanding context; shared history; mutual respect and understanding; member attitudes and beliefs; member satisfaction; processes, organization, and decision-making; communication; determination of goals and objectives; financial and human resources; and leadership [32,33,34]. However, there remains a need to guide partners in how to implement evaluative practices, relate assessment to outcomes, or integrate findings into ongoing partnership management, especially in the case of large institutions coming together for prolonged change. Additionally, further clarity is needed regarding how the general indicator categories of partnership assessment apply to the specific context of partnerships between cities and universities pursuing transformational sustainability outcomes.

Therefore, this paper aims to develop a research-based evaluation scheme for CUPs working on urban sustainability and resilience transformations. The article chronicles the development of an evaluation scheme to plan, monitor, and optimize CUPs for transformative resilience and sustainability outcomes. In so doing, the paper answers the following research questions: How can city–university partnerships be assessed for their capacity to contribute to long-term sustainability and resilience transformation? Specifically, what should be evaluated, who should be involved in the evaluation, and at what frequency? How is this knowledge formatively integrated into CUPs for their improvement? The research questions are answered through a combination of focus groups and evaluation design and application and results include a step-by step guide for real-time sustainability and resilience CUP evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

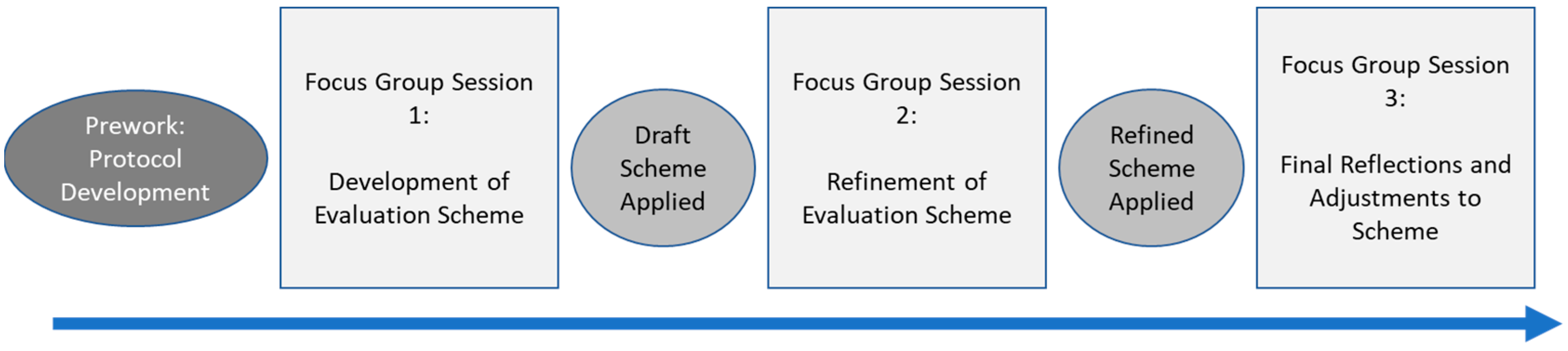

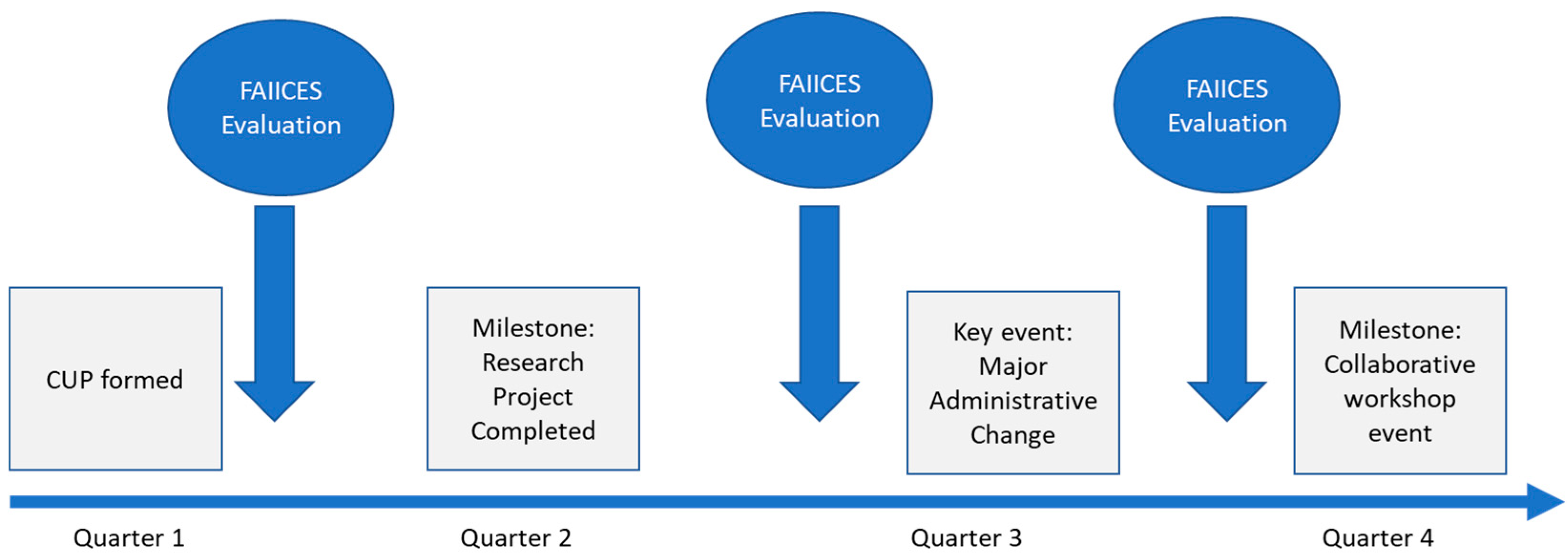

The research team utilized an exploratory and confirmatory iterative focus group methodology as a knowledge elicitation technique to develop an operationalized evaluation scheme for city–university partnerships (CUPs) working on urban resilience and sustainability initiatives [35,36,37]. The focus groups were made up of experts currently involved in the development of transformative sustainability and resilience CUPs and were used to inform possible formative evaluation approaches, indicators, and tools. This consisted of three focus group meetings: one to develop the baseline schema, the second to refine the schema, and the final to reflect on the schema (Figure 1). Between each focus group session, the evaluation technique was applied to the CUP initiatives being undertaken by focus group participants as part of a participatory evaluation technique [38,39].

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the iterative process of focus group sessions to develop the evaluation scheme and application of the draft evaluation scheme.

Focus groups functioned as generative workshops, bringing multiple experts together in one space, and using guiding questions to prompt development of tools, considerations, and opportunities for CUP evaluation. In particular, the groups were asked to think about indicators, metrics, and functional approaches for evaluation based upon their knowledge and skills. The researchers took notes at the focus group sessions which were compiled and sorted to uncover metrics and indicators that met criteria from three prominent collaboration evaluation frameworks: (1) the Collaboration Evaluation and Improvement Framework (CEIF) [40]; (2) the Relationships, climate, and expectations (RCE) framework; and (3) the Extent of collaboration (EC) framework [32]. These findings were then compared to existing literature on transition management and transformative partnerships, specifically, the principals for transferring partnership-based sustainability and resilience solutions across contexts [26]. Finally, metrics and indicators were fit into the deployment mechanics developed by the focus group participants to create the proposed CUP evaluation framework.

Expert knowledge elicitation focus groups were used for this research because they capitalize on communication between research participants in order to generate data. Compared to other types of group interviews, focus groups explicitly use group interaction as part of the method, therefore, people are encouraged to talk to each other, ask questions, exchange anecdotes and comment on each other’s experiences and perspectives [35]. Focus group methodologies are particularly useful for exploratory and applied research; identifying avenues of interest as new fields begin to emerge and when academic literature is thin.

A focus group was developed using a purposive sampling technique. Participants were chosen based upon their experiences in transformative sustainability and resilience CUP development and implementation, connection to inter-institutional partnership initiatives, and experience in research, evaluation, or monitoring of sustainability and resilience related interventions. All participants were currently actively engaged in the implementation of transformative sustainability or resilience initiatives through a CUP at the time of the focus groups, so iterations of the developed formative evaluation scheme could be directly applied.

The individuals selected for focus group participation contained academics and practitioners from five cities around the globe: Portland, Oregon, USA; Mexico City, Mexico; Leuphana, Germany; Karlsruhe, Germany; and Tempe, Arizona, USA. While not statistically representative, this group offered a wide range of experiences and expertise related to sustainability and resilience CUP planning, implementation, and transition management useful for the development of an operationalized evaluation scheme.

The goal of the first focus group session was to determine a starting point for the research and development of a formative evaluation approach for urban sustainability and resilience initiatives that utilize CUPs. There were 10 attendees in the group which consisted of: graduate students, post-docs, faculty members, and practitioners from local government. Attendees were from Germany, Mexico, and the United States. The focus group session was semi-structured, with researchers posing questions and participants responding free form to the questions and to the responses of the other participants.

The session consisted of exploring open-ended questions and prompts, related to how participants currently managed and evaluated their sustainability and resilience CUP work, and what was working well, or experiencing challenges. Questions were used to guide the conversation and to prompt generative and comparative discussion among the participants. Notes were taken and analyzed to develop answers to the questions, which were then combined with best-practices literature (as described above) to develop a formative evaluation scheme. The first version of the evaluation scheme was then applied by the researchers to the focus group participants’ initiatives.

The goal of the second focus group session was to present findings from the first version of the formative evaluation scheme and elicit feedback from the group to refine the scheme. The focus group session was loosely facilitated by the researchers and consisted of exploring open-ended questions and prompts related to the performance of the draft evaluation scheme, how well it represented the work, how findings could be integrated into CUP management, and what might need to be changed. Results from this session were compiled and used to create a refined version of the evaluation scheme, which was subsequently applied by researchers to the participants’ initiatives.

The goal of the final focus group session was to present findings from the application of the refined version of the evaluation scheme and elicit feedback from the group to reflect upon and finalize the scheme. The focus group session was loosely facilitated by the researchers and consisted of exploring open-ended questions and prompts related to the accuracy, usefulness, and overall design of the evaluation scheme. Findings from the session were consolidated and used as final refinements to the evaluation scheme.

3. Results

The focus group sessions and iterative process of evaluation development, deployment, and refinement resulted in a scheme that can be used to assess city–university partnerships (CUPs) for their capacity to contribute to long-term sustainability and resilience transformation. Specifically, results indicated: (1) what should be evaluated, (2) who should be involved in the evaluation, (3) how evaluation data is collected and disseminated, and (4) the frequency at which evaluation should occur. Finally, the results highlight how knowledge generated through the evaluation process can be formatively integrated into CUP management for their improvement.

An in-depth description of the proposed CUP evaluation scheme is described below. It begins with answering the practical questions of who, what, when, where, and why with regard to evaluation. It concludes with a simple step-by-step guide to implement the evaluation.

3.1. Indicators and Measures: What to Evaluate and Why

The focus group sessions and trial evaluations showed that assessing CUP progress requires understanding participant perceptions of both outcome-based and relational aspects of the partnership. Therefore, the proposed scheme includes two domains for evaluation: (1) perceptions of the collaborative project and (2) perceptions of the partnership itself. It is advantageous to gauge the status of these two domains separately, and then integrate knowledge between them for a holistic understanding of the dynamics of the CUP.

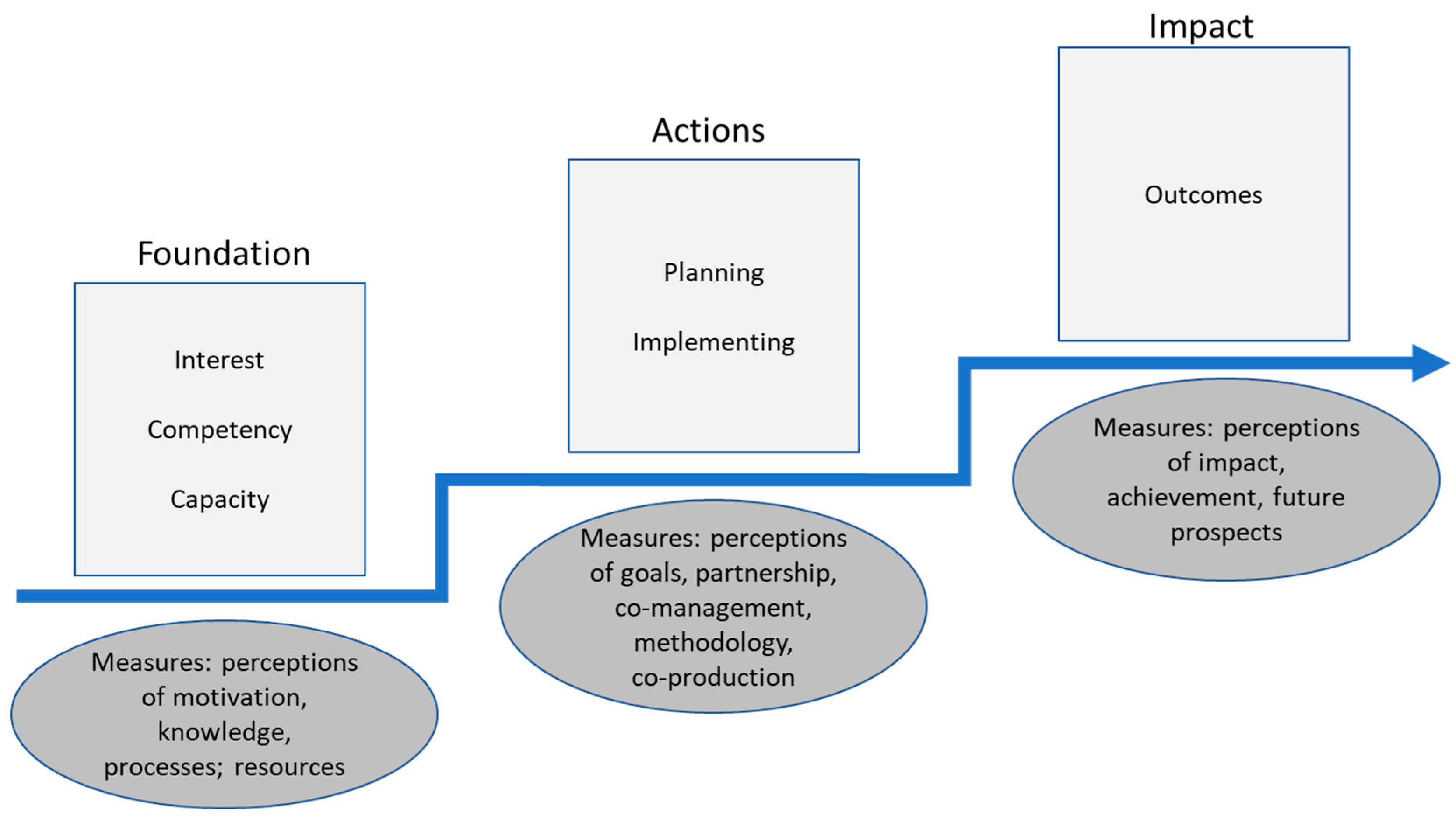

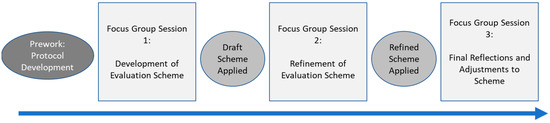

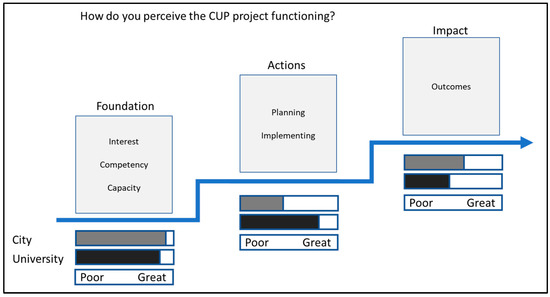

When evaluating perceptions of the collaborative project, three core areas, supported by several reinforcing indicators, are assessed. This is referred to as the Foundation, Actions, Impacts (FAI) assessment of CUP project development, implementation, and outcomes. FAI assessment uses short surveys and informal interviews to gauge participant perceptions related to each indicator (process details elaborated upon in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3). Each of the three core areas are described in further detail below:

- Foundation—Measures CUP participants’ perceptions of interest, competency, and capacity related to project undertaking. Seeks to understand feelings towards own organization and partner organization.

- Actions—Assesses perceived ability of all partners to plan and implement project-related change interventions in a co-created and co-managed way.

- Impact—Evaluates the perceived achievement of project goals and identification of opportunities for future work.

The FAI components are additive over the course of CUP project development and implementation (Figure 2). Findings indicate that when there are deficiencies in one of the earlier stages (for example, lack of interest in the foundation stage), it becomes increasingly difficult for the CUP project to thrive in later stages. By applying the FAI evaluation scheme, such deficiencies can be illuminated and mitigated. Additionally, if progress on the initiative becomes stalled or problematic, using this diagnostic tool can help direct where corrective action should be taken. It can also help identify where support is needed and aid the formulation of goals and plans to better match the evolving circumstances.

Figure 2.

Chart describing three core areas of collaborative project evaluation (foundation, actions, and impact) and how they build upon each other throughout the project timeline.

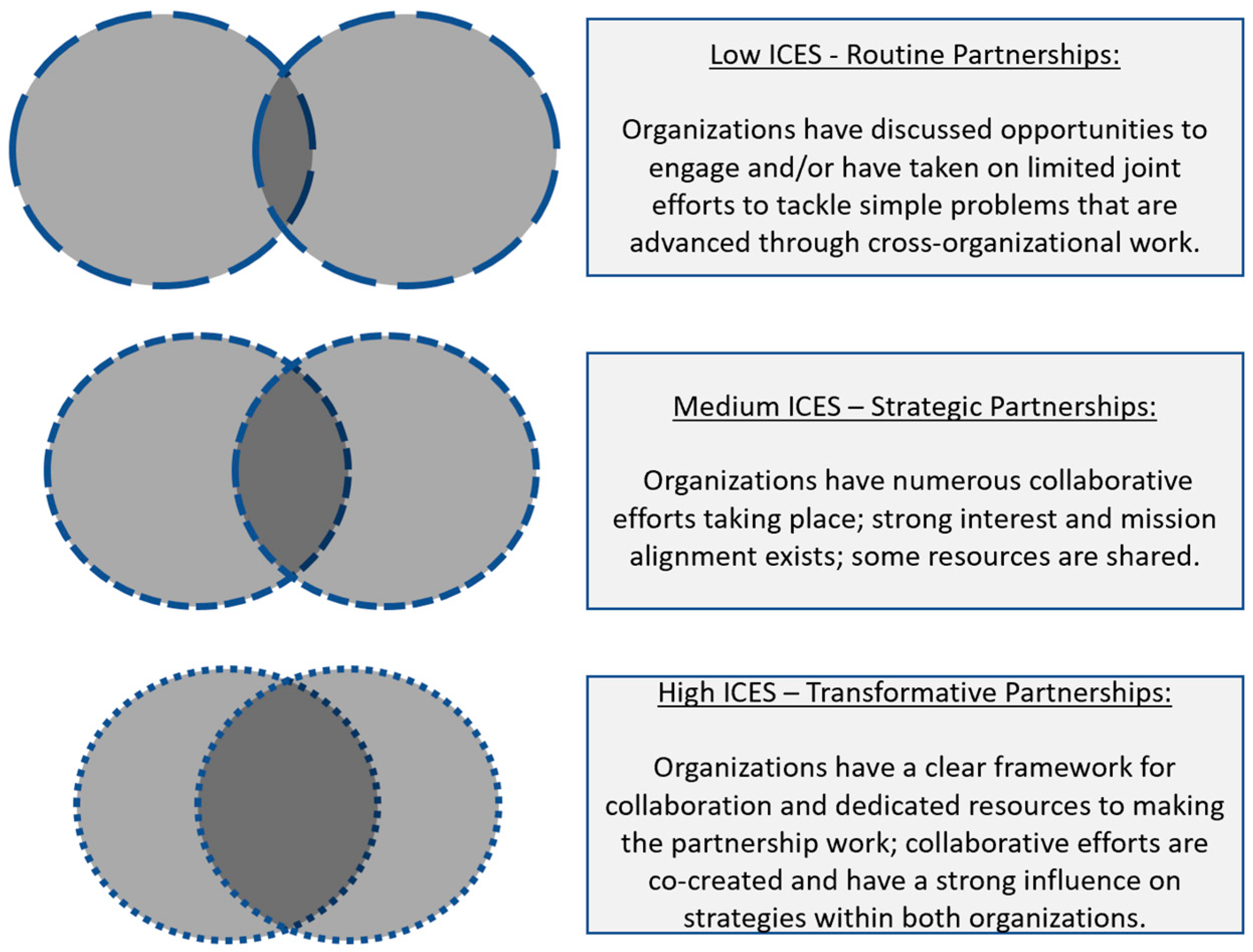

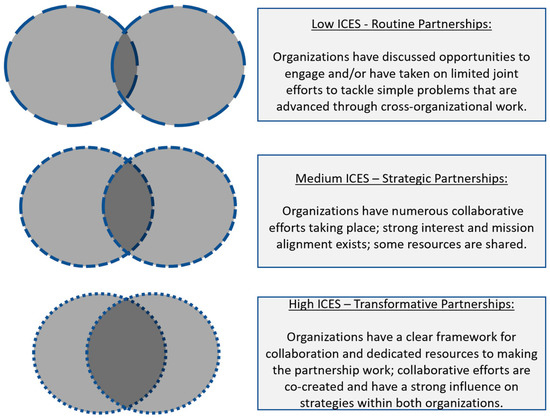

The second domain of evaluation measures participant perceptions of partnership functioning. This is used to understand partnership-specific dynamics, which may or may not be directly related to the current collaborative project. This part of the evaluation can help identify the partnership mode being utilized by the CUP and help participants match their partnership structure to the types of problems they hope the solve and their individual institutional contexts. For instance, if the CUP has transformative aims but the partnership is operating in the routine mode, then the assessment can be used to identify the mismatch and inform methods to shift modes. To measure partnership functioning, the Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (ICES) assessment can be used. The following aspects are considered ICES assessment indicators:

- Interpersonal Context—Measures participant perceptions of collaborative history between institutions, interest to engage, demonstrated motivation to engage, and mutual understanding of need. Seeks to understand perceptions of both own organization and partner organization.

- Empowering Supports—Assesses perceived and/or actual formalization of a partnership, mechanisms of the partnership, and resources committed on all sides of the partnership.

The results of the ICES assessment are compiled to describe the current typology of the partnership and its level of functioning (Figure 3). Findings are divided into three categories, low, medium, and high ICES. Each category relates to a partnership typology, which can be used to understand how well the partnership structure is aligned with desired projects and real-world outcomes. It can also expose when there is malalignment between perceptions of the partnership from different individuals or organizations. This allows for transparent conversations regarding the durability, efficacy, and purpose of the CUP.

Figure 3.

Chart describing Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (ICES) assessment categories and how they relate to the mode and attributes of the partnership.

Taken together, the Foundation, Actions, Impacts and Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (FAIICES, pronounced “faces”) evaluation scheme provides vital information regarding CUP structure and functioning from both a project-based and relationship-based perspective. It offers a mechanism for understanding how partnerships evolve in relationship to project milestones. The FAIICES scheme can be used to find points where the overall CUP system is lacking or out-of-balance, allowing CUP administrators to target efforts in those specific areas. Additionally, it can provide insight into areas where targeted action to develop the partnership, or evolve partnership typology, can be deployed.

For instance, one side of the partnership may be struggling to achieve goals by itself. Through application of the FAIICES evaluation, this could show up as a low score in the Actions category on the project part of the evaluation, and perhaps deficient resources committed on the partnership side. This highlights an opportunity for intervention in specific areas to make an impact; i.e., by facilitating foundational development in content area knowledge or having a tough conversation about shared resources. These capacity-building efforts help develop and align the CUP so that action can flow through the system effectively, and project objectives can be adaptively achieved.

3.2. Actors: Who Evaluates and Who Is Evaluated

The FAIICES evaluation scheme is designed to be participatory and flexible. As a participatory evaluation methodology, it is not meant to be a process where the evaluator is objectively removed, but instead they are an integrated part of the process. This works because the FAIICES scheme is about exploring perceptions of CUP functioning and incorporating findings into CUP management.

Being a participatory method allows for parts of the evaluation methodology to evolve depending on participant needs (especially timing, data collection, dissemination and more discussed further in Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5 below). Therefore, the evaluator can take many forms: From collective team-led evaluation, to a specific person on the team leading evaluation, to a semi-removed evaluator who has ties to the initiative, to an outside evaluator with at least some knowledge of the initiative. Additionally, the evaluator can be more than one singular person. Adherence to the FAIICES scheme is more important than who leads the evaluation.

However, the evaluator also plays an important role in building the evaluative capacity of the team. As evaluation occurs, the evaluator should be sure that the team is understanding the process, purpose, and usefulness of the evaluation, so that it might be conducted by a different entity in the future. In this way, evaluation can become ingrained in CUP management and the responsibility to evaluate can be shared.

Selecting the correct CUP members to be the subjects of evaluation is a more nuanced task. Not everyone who participates in the CUP needs to participate in the evaluation processes. As little as one person from each partner organization is required to complete the data collection portion. Evaluation participants should be central to the functioning of the CUP on both the relational and project-oriented sides. For most CUPS, there are no more than 1–3 key people on each side of the partnership with the insight, power, and positionality needed to be useful for this form of evaluation. The people involved in the evaluation should be the same people who can act on the findings and integrate them into the decision-making and management processes.

3.3. Tools: How to Collect Data and Disseminate Results

The FAIICES scheme can utilize several forms of data collection. We found that a mixture between short surveys and informal interviews, followed by a safe place to collectively examine results, worked well for the participants. One important feature of FAIICES is that it is not rigid; so long as perceptions of the indicators are being gathered, the method in which that occurs is less significant. This is a particularly useful feature when working between multiple institutions. For one side of the partnership, short, pointed surveys with Likert scale answers might best fit into their workflow and norms. Meanwhile, the other side might do better with informal, consultative interviews that get to an understanding of the indicators in a more conversational way. However, they are gathered, compiling the results and fitting them to the FAIICES indicators allows for a subjective, yet informative, comparison between perspectives.

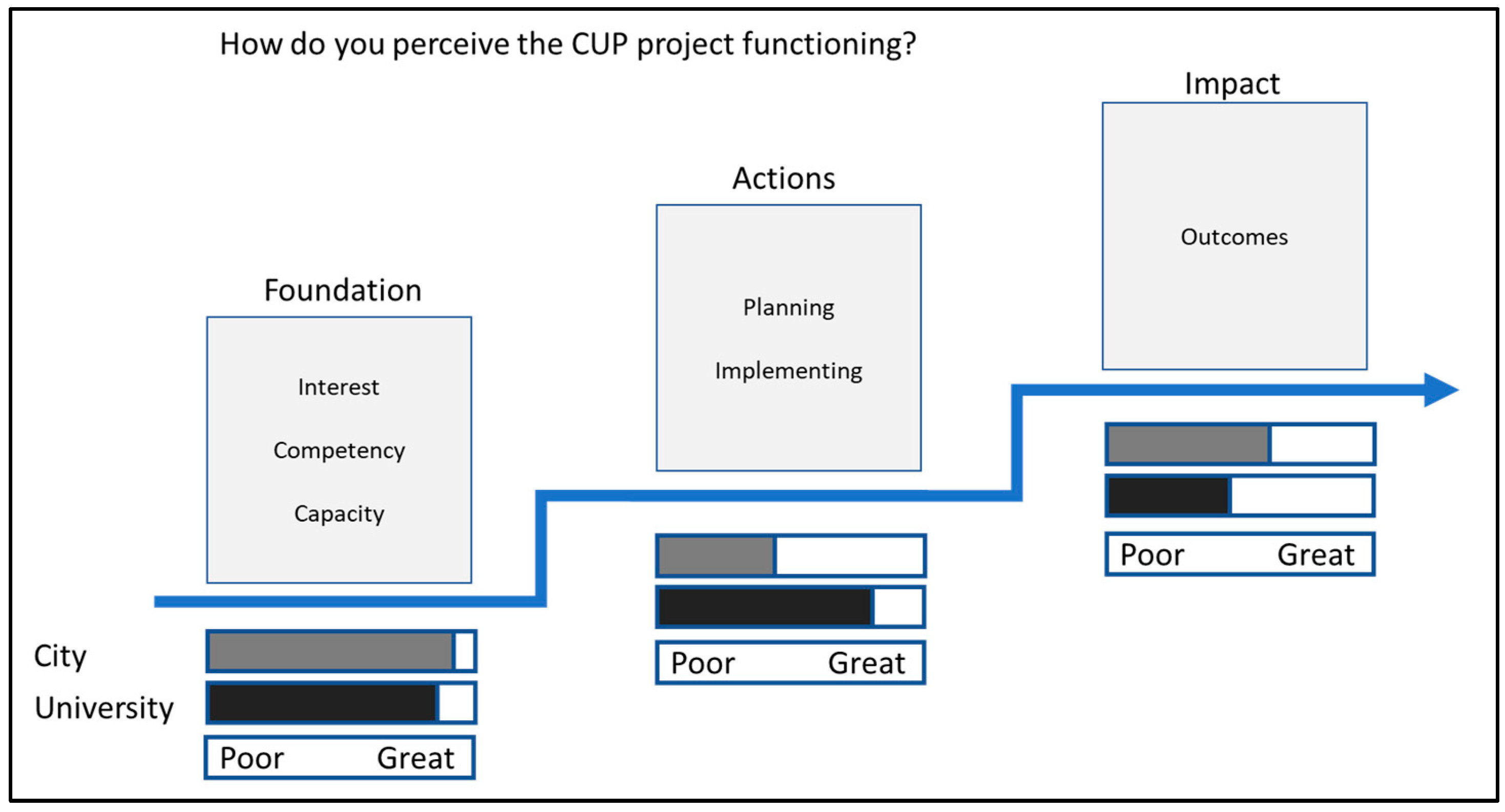

This is a qualitative evaluation tool and evaluators are tasked with interpreting the results from interviews, surveys, etc. and matching them as best they can to the FAIICES attributes. Having a visual representation of results aids understanding and integration of results (see Figure 4 for an example score sheet and visual aid). When sharing the results, it is important to note the qualitative and subjective nature of the findings and note that they should be interrogated and explored. The notion of ambiguity in the results can stimulate more creative thinking and problem-solving in CUP participants.

Figure 4.

Example “score sheet” for a comparison of partners’ perspectives of City-University Partnership (CUP) project functioning across the Foundation, Actions, Impacts and Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (FAIICES) scheme. Here, we can see that the city and university have mostly aligned perspectives regarding the strength of the Foundation but see things differently when it comes to the Actions. This should prompt discussion that explores this difference in perception and hopefully generates solutions.

While only a few people need to actively participate in providing data for the FAIICES analysis, the results of the evaluation can be disseminated more broadly. CUPs vary widely regarding the number of people involved, so dissemination practices need to be developed for specific contexts. If there is a core team of people who meet regularly to work on the CUP initiative, we recommended sharing results at one of these meetings. Here, through active dialogue and discussion, FAIICES findings can be inspected, scrutinized, and affirmed, hopefully leading to the generation of new goals and strategies for improved partnership management and project implementation.

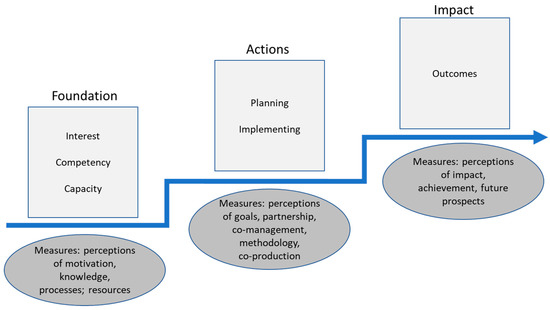

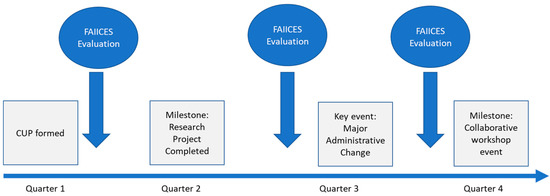

3.4. Timing: When and How Often to Evaluate

Appropriate timing of the FAIICES evaluation is one of the most vital results of this study. The FAIICES scheme should be used iteratively and inform real-time decision-making. Depending on the context of the CUP, the evaluation should be completed about two to four times per project cycle. The timing of evaluation should revolve around key milestones or events, that way findings can be used immediately; results help both reflectively, and for future management decisions (Figure 5). This concept of participatory real-time evaluation has not often been used for CUPs, or other urban sustainability and resilience work. Development and testing of the FAIICES framework showed tangible potential for this approach to be seamlessly integrated into CUP partnership and project management.

Figure 5.

Example timeline for application of Foundation, Actions, Impacts and Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (FAIICES) scheme. Evaluations occur just before or just after key milestones and events that impact the City-University Partnership (CUP). Results from the evaluation should be immediately compiled and used for real-time management and decision-making.

3.5. Knowledge Integration: Using Evaluative Results in Real-Time

As mentioned throughout previous sections, it is imperative for the results of the FAIICES evaluation to be integrated into CUP management and decision-making in real-time. The value of the knowledge generated from the evaluation itself does not compare with the value generated through careful exploration and integration of results by CUP administrators. Collaboratively disseminating and investigating the findings from application of the FAIICES scheme helps to bridge gaps in understanding across institutional barriers and norms. Additionally, the process helps spur conversation and dialogue, which ultimately reinforces mutual understanding and trust.

Knowledge integration from FAIICES often highlights concerns, challenges, and opportunities that CUP participants may not have previously considered. In this way, the evaluation offers insight into leverage-points for higher impact interventions, or elicits strategies for navigating complex political, institutional, and real-world systemic barriers. Continuous, iterative, and strategically timed evaluation can help the CUP evolve and prosper through ever-evolving internal and external circumstances.

3.6. Implementation: Quick Guide to the FAIICES Evaluation Scheme

The FAIICES scheme is simple to begin and can change to suit specific contexts and needs over time. Box 1 shows a quick step-by-step guide for getting started on implementing a FAIICES evaluation:

Box 1. Step-by-step guide for getting started with the FAIICES evaluation scheme.

- Define your city–university partnership—Who is involved, what are your goals, why do you want to undertake this collaborative work?

- Choose an evaluator—Determine whether you want to collaboratively conduct the evaluation, or if you want to identify a specific person or people on your team or entity outside your team to undertake the evaluator role.

- Pick your evaluation participants—Choose at least one central figure from each partner institution to participate in the evaluation. These people should understand both the relational and outcomes-oriented sides of the partnership. They will be the subjects of data collection.

- Determine data collection methods—Decide whether open-ended surveys, Likert scales, informal interviews, or focus group sessions will be best for your participants (and feel free to get creative or adjust over time). Develop questions and prompts to explore participants’ perceptions of project foundation, actions, and impact as well as the partnership’s interpersonal context and empowering supports (see Section 3.1). Example open-ended informal interview questions and guidelines and example open-ended and Likert style survey questions are available in Appendix A.

- Conduct evaluation—Choose an appropriate time to conduct your evaluation, usually just before or after a key event or milestone (see Section 3.4). Get survey/interview responses from your key informants on all sides of the partnership.

- Analyze and compile data—Data analysis techniques will vary depending on the data collection methods used. Therefore, either quantitatively, qualitatively, and/or subjectively compile data to show institution-specific and combined responses for each FAIICES category; depict in a visual format if possible (see Figure 4).

- Disseminate and discuss—Soon after results have been compiled, schedule a time to collectively examine results. At minimum, the people who participated in the evaluation should be present, but this can also be expanded to include the larger CUP team. As a group, (typically led by the evaluator) go through the results, question them, add context, change or reinforce the findings.

- Integrate results into CUP administration—Have the management team think about any opportunities, challenges, or interesting findings that were exposed by the analysis. Question whether these findings indicate that a change in CUP typology, strategy, or goals is needed. Pay specific attention to places where modifications could lead to a better partnership trajectory, or tangible impacts. Finally, decide if and how to respond to these findings, and adjust CUP practices accordingly.

- Repeat FAIICES process—Follow the same instructions at the next appropriate evaluation time; you can then also explore how results change over time for deeper understanding of CUP evolution.

4. Discussion

This paper outlines a multi-faceted tool for the real-time monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of sustainability and resilience city–university partnerships (CUPs) derived from analysis of ongoing sustainability and resilience-focused CUPs. The Foundation, Actions, Impacts and Interpersonal Context and Empowering Supports (FAIICES) evaluation tool is useful for CUPs of all types but is vital for CUPS that aim to be transformative and attain transformational outcomes. The tool offers a mechanism for ongoing data collection on CUPs suitable for future research, and immediate, tangible, useful results for adept management of CUP initiatives as they happen. As municipal governments work towards solutions for exceedingly complex sustainability and resilience problems, CUPs are emerging as a strategy to accelerate learning, build capacity, and confront institutional barriers [14,15]. Successful CUPs will match the structure of their partnership to their sustainability goals. However, there is limited research on CUPs to improve their performance. This paper provides the FAIICES evaluation tool as one mechanism to guide the design and management of sustainability and resilience-oriented CUPs, in an effort to improve their contributions to sustainability outcomes.

If a CUP is interested in tackling the complexities of urban resilience and sustainability through long-term collaboration, establishing and maintaining a transformative partnership will be critical. In transformative partnerships, cross-institutional partners retain their identities but are willing to learn from and with each other through prolonged, deep engagement. Partners approach their common purposes in a profoundly collaboratively way and exhibit a greater willingness to promote deeper systemic changes both internally and externally [25,41]. While not all CUPs need to be transformative, many CUPs that are working on sustainability transformations are not achieving their goals or generating real world outcomes. This may be due, in part, to a mismatch between partnership structure and the specific problems and context. Successful transformative partnership administration calls for understanding how to think systemically and manage within systems. The FAIICES scheme offers users a way to reconcile their current partnership mode with their goals and develop pathways toward alignment.

How the FAIICES scheme is implemented matters. Effective implementation must: gauge perceptions of the CUP from all sides of the partnership; explore both relational and outcome-oriented aspects of the CUP; and occur in real-time (i.e., well-timed iterative formative evaluation for adaptive management). Gauging CUP participants’ perceptions of and perspectives on the indicator areas of interest proved to be more useful than measuring quantifiable metrics. Our results confirm that for the purposes of agile management and decision-making, perspectives play a critical role. For example, what one partner perceives as interest to engage from their collaborator matters more for relationship development than the actual measurable interest, i.e., impact is greater than intent. Future work should aim to connect methods of quantitative analysis to the FAIICES findings to better understand how the varying indicators relate to CUP outcomes and the qualitative measures used in this approach.

Additionally, our findings show that the project-based component and relationship-based component of the CUPs should be assessed separately but considered collectively. This is not often done in research on sustainability and resilience collaborations, as most research either focuses solely on project outcomes or solely on the collaboration itself [42]. With the FAIICES evaluation scheme, the relationship between these two domains is better understood, and can be used to make decisions that span across the domains. Future research should apply the FAIICES framework with an eye towards understanding the dynamics between the two domains, and how their interplay impacts CUP functioning and outcomes over time.

One of the biggest value-propositions that is generated by using the FAIICES tool is the ability to both collect data for immediate and longitudinal studies of CUPs while also immediately integrating findings into the CUP development, management, and implementation process. Historically, implementers have tended towards summative evaluation, which entails analysis of results compared to goals at the end of an intervention process used to make a judgement regarding efficacy [43]. Unfortunately, summative assessments often go uncompleted, or they occur after an intervention has ceased, so results cannot be directly integrated into implementation [44]. This is in direct contrast to the formative evaluation strategies that have been suggested by the sustainability and resilience transition management literature. It is suggested that complex work should be constantly re-evaluated and re-adjusted (adaptively managed) in an iterative way that supports agile decision-making and learning [29,45]. Our findings from this study confirm these results.

Finally, while this tool was developed specifically for city–university partnerships that are working on complex urban sustainability and resilience topics, it is possible that it can be useful for a much broader context. The FAIICES tool itself does not ask any resilience or sustainability-related questions; it also is not specific to the constraints of municipal governments or research universities. The metrics are focused on co-management, institutional alignment, and process in such a way that they are likely applicable to a wide range of collaborative efforts, especially those working on exceedingly complex or transformative issues. Further work is needed to understand how FAIICES might be applicable to these varying contexts.

Author Contributions

L.C., L.W.K., and F.B. designed the cross-case analysis. L.C., under the supervision of L.W.K. and F.B. conducted, conducted the focus groups and led the writing up of results. W.K. and F.B. also contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Global Consortium for Sustainability Outcomes (GCSO) (sustainabilityoutcomes.org) under the grant titled CapaCities: Building Capacity in City Administrations for Sustainability and Resilience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Example open-ended informal interview questions and guidelines and example open-ended and Likert style survey questions are available for reference:

Open ended interview

- Please describe the approach you are using for your collaborative project. Has your approach changed?

- Where would you like to be a year from now? Why? What do you need to get there?

- What are the impacts you envision from your project? From your partnership?

- Who do you work with at the city/university?

- What challenges are you currently facing? What opportunities do you see?

- What have you learned from using the real-time evaluation tool so far? What has been most helpful or hurtful and why?

Open ended survey

- What is your relationship to this project?

- What is the goal of this project?

- What are the primary actions being taken to support these goals?

- State the primary individuals and organizations involved in this project. Who are the leads?

- Please describe where you are currently at within the project timeline (i.e., phase 1 of a 3 phase project, or month 6 out of a yearlong project).

- Will this project have permanent sustainability impacts that endure after the project has been completed? Please explain.

- At the university, are there a variety of academic positions (including students, researchers, and faculty) that are interested in the topic of this project? Please explain.

- At the city are there a variety of staff interested in the topic of this project? Please explain.

- At the university, how would you describe the level of understanding of the project topic? Do they have the skills and abilities needed to complete this project?

- At the city, how would you describe the level of understanding of the project topic? Do they have the skills and abilities needed to complete this project?

- Does the city have all of the resources (time, money, personnel, etc.) needed to undertake this project? Please explain.

- Does the university have all of the resources (time, money, personnel, etc.) needed to undertake this project? Please explain.

- Does the university have the ability to engage students in this work and/or provide them with related research opportunities? Please explain.

- Does the university have experience working as a convener (i.e., bringing together multiple stakeholders)? Please explain.

- Please describe the level of trust between the city and university regarding this project.

- Please describe the level of communication between the city and university regarding this project.

- Please describe the level of commitment to this project. Are both sides of the partnership fully dedicated?

- Have the roles and responsibilities regarding project scoping and management been well defined, agreed upon, and co-created by both sides of the partnership? Please explain.

- Have the roles and responsibilities regarding fundraising and communications been well defined, agreed upon, and co-created by both sides of the partnership? Please explain.

- Have the roles and responsibilities regarding scheduling, meeting, and planning been well defined, agreed upon, and co-created by both sides of the partnership? Please explain.

- A reference document that memorializes the partnership has been created and agreed upon by both sides of the partnership.

- Before this project began, what actions had been taken by the city to work towards the topic of this project? i.e., City council announced that they would make a climate action plan.

- Since this project began, what actions have been taken by the city to work towards the goal of this project? i.e., City officers have attended 2 workshops to start visioning the climate action process.

- Before this project began, what actions had been taken by the university to work towards the topic of this project? i.e., multiple publications on climate mitigation strategies has been produced.

- Since this project began, what actions have been taken by the university to work towards the goal of this project? i.e., University hired students to coordinate and facilitate climate action planning workshops.

- Is the partnership structure being used to co-develop and design project activities? Please explain.

- Based on your own personal understanding and assessment of the project, do you feel that the goals of this project have been achieved? Please explain.

- Do you envision future projects that build off this project and can utilize this partnership? Please explain.

- Do both sides have a desire to be partners with each other? Please explain.

- What drives the participation in the partnership? What do the partners hope to gain from partnering?

- Do both sides of the partnership have enough motivation to enable dedication to the partnership? Please explain.

- Are both sides of the partnership willing to do what it takes to actively engage in the partnership? Please explain.

- Please rate your satisfaction with the level of motivation to partner and willingness to engage in partnership:

- Have you and your partner completed projects together in the past? Please explain.

- Were you satisfied with the outcomes of the past projects and your experience with the partner? Please explain.

- Are both sides of the partnership committing resources (time, money, personnel, etc.) to the development of the partnership itself? Please explain.

- Have roles and responsibilities in the partnership been outlined and agreed upon? Please explain.

- Are there documents that specifically state the goals and/or purpose of the partnership? Please explain.

- Would you describe both sides of the partnership as feeling empowered and valued in the partnership? Please explain.

- Do the partners have an understanding of each others needs? Please explain.

- Do the partners have an understanding of each others mission and priorities? Please explain.

- Does the partnership influence the internal strategies at both organizations? Please explain.

- Have the partners aligned their missions, in the context of the partnership? Please explain.

Likert scale 1 to 5

- Please rate your satisfaction with the sustainability impacts this project aims to produce:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the overall amount of interest in the topic of this project:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the level of capacity for this project:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the level of co-management for this project:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the actions that have been taken by this project:

- Please rate your current satisfaction with the outcomes and impacts that have been achieved by this project:

- Overall, rate your current level of satisfaction with the progress and functioning of the project:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the history of collaboration with your partner:

- Please rate your level of satisfaction with the resources that have been committed to the partnership:

- Please rate your satisfaction with the level of mutual understanding in the partnership:

- Overall, rate your current level of satisfaction with the progress and functioning of the partnership:

- Please rate your level of satisfaction with the structure of the partnership overall:

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. 2020. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300 (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- C40. 2020. Available online: https://www.c40.org/why_cities (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Acuto, M.; Parnell, S.; Seto, K.C. Building a global urban science. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauslar, N.J.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Marsh, P.T. The 2017 North Bay and Southern California Fires: A Case Study. Fire 2018, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.; Boer, M.M.; Collins, L.; de Dios, V.R.; Clarke, H.; Jenkins, M.; Kenny, B.; Bradstock, R.A. Causes and consequences of eastern Australia’s 2019–20 season of mega-fires. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickrell, J. Will Australia’s Forests Bounce Back after Devastating Fires? Science News. 11 February 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/australia-forest-ecosystem-bounce-back-after-devastating-fires (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Wolfram, M.; Borgström, S.; Farrelly, M. Urban transformative capacity: From concept to practice. Ambio 2019, 48, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability transformations: A resilience perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, L.W.; Beaudoin, F.; Wiek, A.; John, B.; Lerner, A.M.; Beecroft, R.; Tamm, K.; Seebacher, A.; Lang, D.J.; Kay, B.; et al. Building actor-centric transformative capacity through city-university partnerships. Ambio 2018, 48, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures 2015, 65, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Collaboration as a pathway for sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughman, L. Collaboration and Evaluation in Urban Sustainability and Resilience Transformations: The Keys to a Just Transition? Ph.D. Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, A.; Bettencourt, L.; Clarens, A.; Das, S.; Fitzgerald, G.; Irwin, E.; Pataki, D.; Pincetl, S.; Seto, K.; Waddell, S. Sustainable Urban Systems: Articulating a Long-Term Convergence Research Agenda; National Science Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trencher, G.; Bai, X.; Evans, J.; McCormick, K.; Yarime, M. University partnerships for co-designing and co-producing urban sustainability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, L.W.; Beaudoin, F.D.; Lerner, A.M.; John, B.; Beecroft, R.; Tamm, K.; Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J. Transferring Sustainability Solutions across Contexts through City—University Partnerships. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, E.L.; Perry, D.C.; Taylor, H.L., Jr. Universities as Anchor Institutions. J. High. Ed Outreach Engag. 2013, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Holley, K. Universities as Anchor Institutions: Economic and Social Potential for Urban Development. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Paulsen, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Poutanen, P. Success factors of innovation ecosystems—Initial insights from a literature review. In Proceedings of the CO-CREATE 2013: The Boundary-Crossing Conference on Co-Design in Innovation, Helsinki, Finland, 16–19 June 2013; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila, P.; Eisenbart, B.; Kocsis, A.; Ranscombe, C.; Tuulos, T. Transformation is a game we can’t play alone: Diversity and co-creation as key to thriving innovation ecosystems. In Research into Design for a Connected World; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 135, pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, L.W.; Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J.; Yokohari, M.; van Breda, J.; Olsson, L.; Ness, B.; Morató, J.; Segalàs, J.; Martens, P.; et al. Utilizing international networks for accelerating research and learning in transformational sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPIC-N. Who’s in the Network. 2020. Available online: https://www.epicn.org/whos-in-the-network/ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Margerum, R.D. A Typology of Collaboration Efforts in Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitel, L. School/Uníversíty Collaboratíon: The Power of Transformative Partnerships. Child. Educ. 2008, 85, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.; Bezzina, M.; Moran, W. Transformational Partnerships: A New Agenda for Higher Education. Altern. High. Educ. 2010, 36, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula-Semos, M. Seeking Transformative Partnerships: Schools, University and the Practicum in Papua New Guinea. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, Douglas, QLD, Australia, 2009. Available online: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/15463/ (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Swartz, A.L.; Triscari, J.S. A Model of Transformative Collaboration. Adult Educ. Q. 2010, 61, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.D. The North Carolina Policy Collaboratory: A Novel and Transformative Partnership for Decision-Relevant Science; Fall Meeting; Abstract #PA43A-08; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2018AGUFMPA43A..08W (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Salimova, T.; Vatolkina, N.; Makolov, V. Strategic Partnership: Potential for Ensuring the University Sustainable Development. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2014, 18, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luederitz, C.; Schäpke, N.; Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J.; Bergmann, M.; Bos, J.J.; Burch, S.; Davies, A.; Evans, J.; König, A.; et al. Learning through evaluation—A tentative evaluative scheme for sustainability transition experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Fraser, E.D.; Dougill, A.J. An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 59, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, H.P.; Zukoski, A.P. Assessing Collaboration. Am. J. Eval. 2018, 39, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, L.I.; Brock, D.J.P.; Savla, J. Evaluating Collaboration for Effectiveness. Am. J. Eval. 2014, 36, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodland, R.H.; Hutton, M.S. Evaluating Organizational Collaborations. Am. J. Evaluation 2012, 33, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative Research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, A.; Wallace, W. Focus groups as a knowledge elicitation technique: An exploratory study. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 1991, 3, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.C.; Hevner, A.R.; Berndt, D.J. The Use of Focus Groups in Design Science Research. In Design Research in Information Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Campos, L. Advances in collaborative evaluation. Eval. Program Plan 2012, 35, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmore, E.E. Understanding and Practicing Participatory Evaluation. New Dir. Eval. 1998, 80, 1–104. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ580835 (accessed on 29 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.D.; Feinberg, M.E.; Greenberg, M.T. Measuring coalition functioning: Refining constructs through factor analysis. Health Educ. Behav. 2011, 39, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidi, M.M.; Koufopoulos, D.N.; Palmer, P. Partnership Formation for Change: Indicators for Transformative Potential in Cross Sector Social Partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, A.; Santoro, G.; Papa, A. The cities of the future: Hybrid alliances for open innovation projects. Futures 2018, 103, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faehnle, M.; Tyrväinen, L. A framework for evaluating and designing collaborative planning. Land Use Policy 2013, 34, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyadeen, D.; Seasons, M. Evaluation Theory and Practice: Comparing Program Evaluation and Evaluation in Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2016, 38, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Armitage, D. A resilience-based framework for evaluating adaptive co-management: Linking ecology, economics and society in a complex world. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).