1. Introduction

The ideas developed in this article are restricted to the organizational domain and they take as a reference the sustainability concept from the international encyclopedia of systems and cybernetics, mentioning that organizational sustainability is an emerging property that cannot be achieved through linear processes and that interdependence is necessary to cope with complexity in the environment [

1]. Therefore, this work focuses on small and medium-sized companies (SMEs), particularly tourism SMEs lodging and restaurant (lodging and restaurants organizations).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

2] declares that SMEs are a crucial link in economic dynamics, especially in emerging regions, since they represent around 90% of their commercial activity. This research uses Mexico as the context for its application, where tourism activity is preponderant because it generates around 5,250,600 formal jobs and contributes an estimated 190 million dollars to the gross domestic product, to put this in perspective this activity represents 12% of GDP and 10% of formal employment [

3]. Despite their importance, these organizations face challenges that affect both their operations and their ability to adapt to a changing and uncertain environment, without neglecting the customers’ demands. Gómez López and Barrón Arreola [

4] indicate that Mexican SMEs show similar pathologies to those reported at the international level, including poor planning, unclear objectives, weak management, inconsistent relationships between their operating units, absence of control and coordination mechanisms and little coherence between the management model and the accomplishment of goals. In this brief context, it should be added that organizational sustainability and sustainable performance continue to be a challenge for different SMEs because their resources and organizational structure limit them. Additionally, sustainability is subject to transversal policies that demand a harmonious relationship among organizations, the environment and social, economic and governmental actors [

5]. This is considered to be a problem because, according to Purvis et al. [

6], no clear elements have been identified that would allow SMEs to be certain about which factors to consider in order to adopt and operationalize sustainability. Acevedo-Osorio et al. [

7] emphasize the importance of addressing these types of problems because they consider it necessary to help these types of companies through guidelines that allow them to move towards sustainability in an environment in which the gradual reopening of businesses will require adaptability and constant equilibrium.

Consequently, in this research, several components were identified and presented through a conceptual model to propose interactions that promote tourism SME’s organizational sustainability. The construct was developed with the participation of tourists, staff, managers and owners of different tourism SMEs to consider different perspectives on the problem. Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) was used as the guiding methodology to achieve the following objectives: A) structure the problem and identify relevant components using Social Network Analysis (SNA); B) based on that information, propose a construct that serves as a starting point for the change process; and C) finally, estimate the conceptual models validity through the Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) technique.

2. Literature Review

According to Acevedo-Osorio et al. [

7], sustainability is a factor that contributes to the permanence and success of any organization. However, tourism SMEs find it challenging to put it into practice at any level. Romero-García et al. [

8] state that literature on tourism-related topics focuses on major themes, such as marketing, information systems, management of large companies or destinations, case studies, economic studies, social studies and statistical models. However, few studies related to organizational sustainability are identified that allow tourist SMEs to generate innovative strategies that enable them to stay in business. The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) [

3] highlights that, despite economic complications, the last 20 years have meant growth for tourism activity. It also indicates that one of the most significant current challenges is to consolidate organizations that operate under a management model oriented towards respectful interactions with the environment. In this context, Singh [

9] distinguishes the “eco-entrepreneur” and “eco-manager” as necessary agents of change in such a challenge. However, the author concludes that these actors’ perception of the environment is highly influenced by their economic benefit, which constitutes a factor that deviates from and neglects an organization’s efforts to achieve sustainable performance.

In this brief context, Mikulić et al. [

10] establish that the study of sustainability in tourism should be strengthened because there are still gaps, such as its implementation, especially in SMEs. In this regard, it is worth highlighting the relevance of quantitative tools that help reduce the gap related to organizational sustainability. There are some previous contributions that use PLS-PM to approach sustainability issues in organizations in the tourism sector. For example, Campón-Cerro et al. [

11] analyzed different components that can make a tourism company sustainable. They found elements that management should monitor and develop, such as the company’s image and the quality of services, as they constitute pillars of a strategy that allows a positive impact on both the satisfaction and the preferences of tourists. Oviedo-García et al. [

12] address sustainability in tourism enterprises from the perspective that it is a consequence of user satisfaction. Based on this, they proposed to analyze the relationship between ecological knowledge, which organizations have, users and strategies to meet customer needs. Their results indicate that sustainability will affect satisfaction positively only when a site or tourism company is perceived as something of value by users.

Loureiro [

13] empirically explored the effects of elements, such as economy, experience and attachment to a place and behavioral intentions through emotions and memory, to evaluate the role of sustainability on a tourist destination and the businesses therein. In this regard, he found that variables such as liking, emotion and memory are mediating elements between experience and behavioral intentions; that is, there is a high probability that a user would memorize and recommend a particular destination or company if these adequately appeal to them emotionally. However, he recognized a limitation of the study: the effect of affection, emotion and attachment on a particular place was not properly supported. In this same line, Rajaratnam et al. [

14] and Chin et al. [

15] Castellanos-Verdugo et al. [

16] examined user perceptions of service quality in tourist destinations and found that perceived service quality has a significant positive influence on tourist satisfaction; furthermore, previous experience moderates the relationship between perceived service quality and satisfaction. It is worth mentioning that both contributions agree in suggesting that it is necessary to foster relationships between managers from other organizations to provide mutual feedback and seek joint improvements in terms of management.

By relating social aspects to organizational growth, Faizal et al. [

17] emphasize that sustainability in tourism enterprises means that they must consider the development of those who live around tourism sites. Based on this, he determined the effects of different variables, such as the level of community participation and how they affect or condition an organization’s management. To this end, the variables considered in the study were characteristics of the community, perceptions, norms, patterns of social relations and trust. It should be noted that one relevant finding is that most tourism SMEs do not consider the information from and participation of society as inputs that allow them to improve their models of management and operation schemes. In this regard, the consolidation of destinations and new opportunities for tourism companies encourage the upward trend in actors participation in the sector. This poses a problem for the communities and their authorities, which must continue growing without jeopardizing the environment. By applying PLS, as in previous contributions such as Rasoolimanesh et al. [

18], Pérez et al. [

19], Villanueva-Álvaro et al. [

20] and Carrillo and Jorge [

21], from the perspective of supply, they can study the environmental impacts of both the tourists’ activity and companies’ management models. Hashim and Haque [

22] investigated the relationship between the equity of the service experience and behavioral intent in ecologically oriented businesses. Their findings highlight that the equity of the perceived service experience significantly influences the intention to choose sustainable companies; another relevant aspect is the strong relationship between factors such as size, organizational and structural capabilities with suppliers and achievement in terms of sustainable performance.

Trying to understand a user’s attitudes towards sustainability in a destination or towards tourism enterprises has been a recurrent concern in adapting regional or local strategies [

23]. From this perspective, there are studies that integrate different views and analyze aspects such as the support of residents and the possible economic and social benefits of sustainability, as well as local community participation. Considering this, authors such as López et al. [

24] have reported that perceived benefits have a more significant effect on tourism sustainability than resident support. This supports the argument that the benefits of tourism positively affect the cohesion of a community.

Concerning the ideas expressed by the authors previously referred to, Jaya et al. [

25], Purvis et al. [

6], Martos-Pedrero et al. [

26] measured the effect of the image of the destination and the perceived value, as well as the user satisfaction, having as context a visit to an area oriented to sustainability. The authors determined that destination image, perceived value and satisfaction shape the user’s actions, depending on the rules of the place they visit. Additionally, these authors found that users are more willing to recommend a site that meets ecological standards. This variable presented high correlations with the perceived value compared to the image of the destination and satisfaction. This indicates that managers should modify the cost of their operations so that tourists get the benefits they expect. Other implications of the above results are that it is necessary to adjust the evaluation of personnel, material acquisition and functional value. According to the authors, this is based on data indicating that tourists visiting the site make complex comparisons about the service and experiences they received during a visit.

It is pertinent to mention that more robust techniques have been adopted to study subjective variables around sustainability in the tourism sector. In this regard, it is possible to refer to the contributions of Purvis et al. [

6] and Martos-Pedrero [

26], which say that we should, through PLS, analyze perceived behavior, perceived ecological utility, ecological value and the intention of engaging in ecological behavior. These authors agree and indicate that the interaction of these variables explains and influences the adoption of sustainability. They also emphasize that managers are change-makers and that their participation promotes the adoption of a model’s components in order to operate sustainably.

Up to this point and, according to Kanwel et al. [

27], the empirical studies referred to have demonstrated the connection of the natural dimension and its usefulness to promote tourism as an economic activity. These studies have also shown that nature-attachment to place and community incidence is related to the intention of operating in a sustainable manner. However, according to Perrotti et al. [

28], it is necessary to move from the analysis of subjective variables to the construction of models that seek to identify relevant factors to operationalize the balance between the sector’s economic activities and its context.

According to Ison et al. [

29], the current context imposes new challenges on governments, businesses and social groups that benefit from or are affected by their interactions. It also requires the capacity to deal with complexity and uncertainty, which entails examining and proposing new avenues and effective ways of interaction among the actors, as mentioned earlier, to positively impact the socio-ecological dynamic, subject to and limited by processes and systems that follow a top-down and mechanistic logic.

Some works address issues related to sustainability from the systems thinking perspective. This approach demands an understanding of interconnections between different domains, such as nature and society, as well as the openness and willingness of those involved to adopt multi-methodological approaches to generate courses of action without ignoring internal relations and the context in which they operate. In this regard, Espinosa et al. [

30] highlight the need to apply the systemic approach, so that management tries to adapt and continuously seek a sustainable state without neglecting the relationships between companies, government actors and the community of inhabitants; to achieve this, they suggest using different models and methodological tools that allow the researcher to deal with any system’s structural, relational and functional dimensions.

Multi-criteria tools and systems analysis are recurrent because they provide suitable alternatives for evaluating sustainability problems. With these tools, Bausch et al. [

31] proposed a flexible framework to address socio-ecological system’s problems. However, it highlights that one of the pending challenges is identifying internal components that contribute to the application in organizational terms. Within the systems thinking framework, Schwaninger [

32] considers that the Viable System Model has been reported as a feasible approach to sustainability issues [

33,

34,

35], since problems in that context are characterized by the absence or deviation of controls at the operational level as well as a lack of coordination between coordination and management levels. In this context, this model provides a set of guidelines and criteria to design flexible organizational structures oriented to search for constant balance between actors and their context [

36].

Regarding the use of approaches based on cybernetic-systemic criteria, Schwaninger [

37] indicates that they are ideal for suggesting improvements for socio-economic systems, since they specialize in dealing with complexity and offer new transdisciplinary forms of system design to renew sustainability. For example, Espinosa and Duque [

38] propose a structure to help indigenous associations in the Amazon to achieve sustainability. To this end, they standardize all organization scales to ensure the transmission of information between levels. Additionally, they apply the model to positively influence self-government practices without ignoring integration and collective decision-making practices. In this sense, Schwaninger [

37] applies these approaches to propose a structural design that allows society, business, government, the economy and the technology sector to move toward what he calls sustainable recovery.

It is considered pertinent to add that, from a systemic perspective, sustainability can and should be considered as a state of the specific structures that mediate it. This differs fundamentally from the idea of considering the capacity to sustain oneself as a simple normative end. In this sense, Weitz et al. [

39] used System Dynamics (SD) to simulate the long-term relationships of socio-ecological systems, seeking to improve interactions between regions by introducing and strengthening feedback and control measures. Ben-Eli [

5] adopted the same perspective and identified the types of structures that shape a system’s state because, according to the author, this encourages the design of structures and mechanisms necessary to promote sustainability. For this, in addition to understanding the material, economic and social domains, it is necessary to homologate principles that allow sustainability to be an inherent characteristic when designing socio-technical systems. These proposals justified multi-methodological approaches. For example, Shahabi et al. [

40] attempted to address the process of determining the dimensions of formal collaborative networks to shape cooperation as a means of joint success. Through the SSM, these authors detected involved actors and contradictory interests among the parties and integrated them in a cooperative network model that continuously seeks sustainable operation. Later, using SD, they proposed a model that highlights important factors and focuses on the orchestrator’s capacity to induce and enhance the participants’ confidence and motivation, the members’ socialization process and sustainability. Thus, it is possible to say that if, when studying sustainability, the systemic nature of the problems is recognized, a common conceptual and methodological framework could be obtained to propitiate the exchange of knowledge that would allow every socio-ecological system, firstly, to change internally to be able to adapt to the disruptions of the environment [

41]. Subsequently, the need to adopt the systemic approach in the processes and design of strategies to deal with sustainability problems is highlighted [

7].

4. Results of Applying SSM and PLS-PM

Stages 1 and 2: The participants answers shaped the problem situation of organizational sustainability in tourism SMEs, by allowing us to know what factors to assess to improve the problem, seeking to meet the needs of both customers and SMEs.

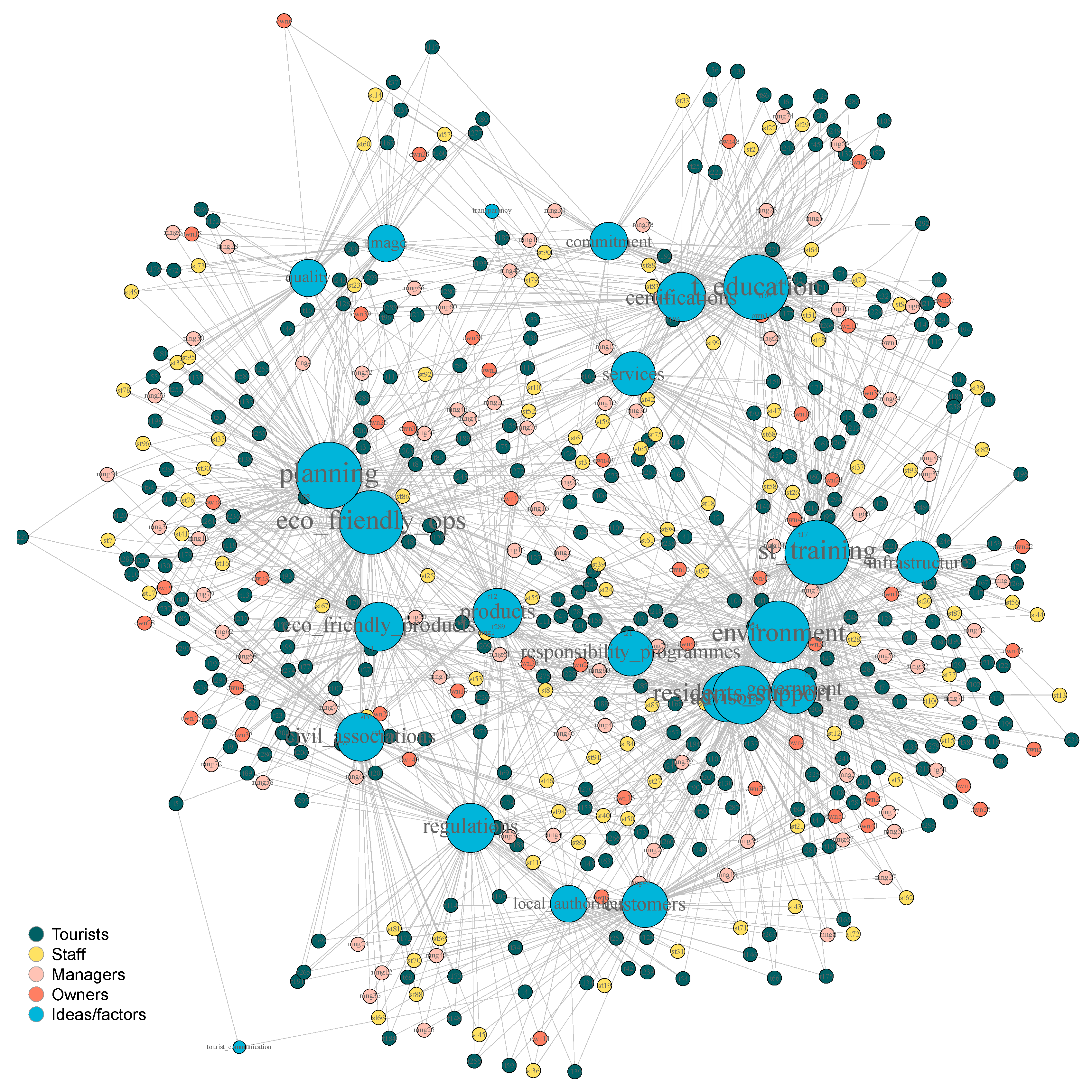

Figure 1 shows a two-mode network that represents the relationship between participants and ideas. From a global perspective, in this first network, the relevant components that an SME must address are its operations, its relationship with the environment, its staff training and its planning process; additionally, aspects such as user or tourist education and local community support are more representative than obtaining certifications, infrastructure or assistance from advisors or local and government authorities.

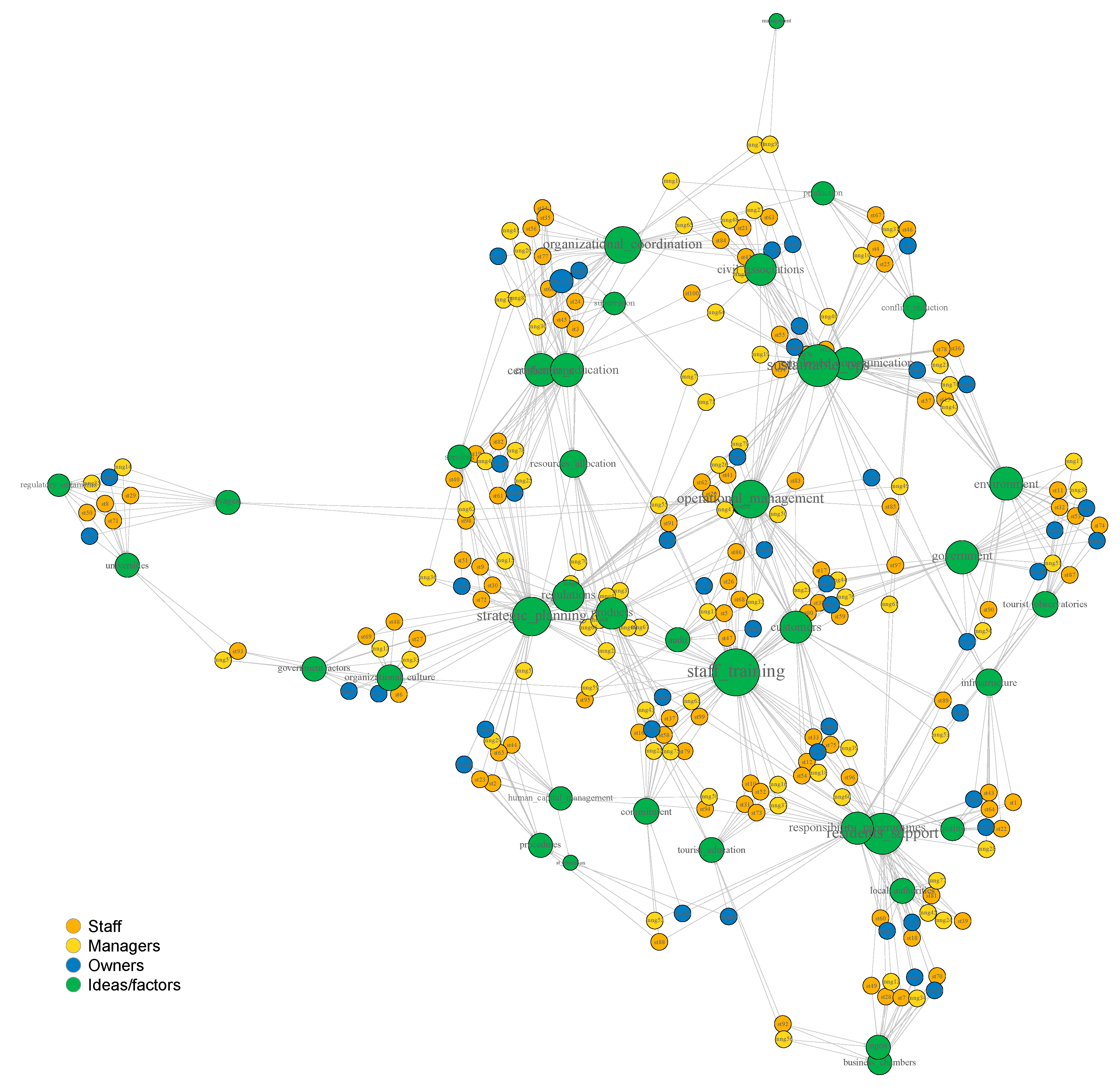

Figure 2 also shows a two-mode network representing the relationship between actors within organizations and ideas about which elements hinder organizational sustainability. This coincides with customers perception by highlighting factors such as strategic planning, sustainable operations, staff training and resident support; additionally, emerging facets include coordination, operational management, certifications and relationships with government actors.

Stages 3 and 4: The information from the previous stages allowed us to name relevant variables and suggest relationships between them to propose an alternative to improve the problem. Likewise, minimum but sufficient components that allow the operationalization of the change were identified using the Clients, Actors, Transformation, Weltanschauung, Owner and Environment (CATWOE) mnemonic (

Table 1). Following the SSM framework, the root definition is used to give meaning to this process. In that sense, the following root definition was stated: A conceptual model for tourist SMEs that supports management in striving for sustainability through reconsidering organizational interactions.

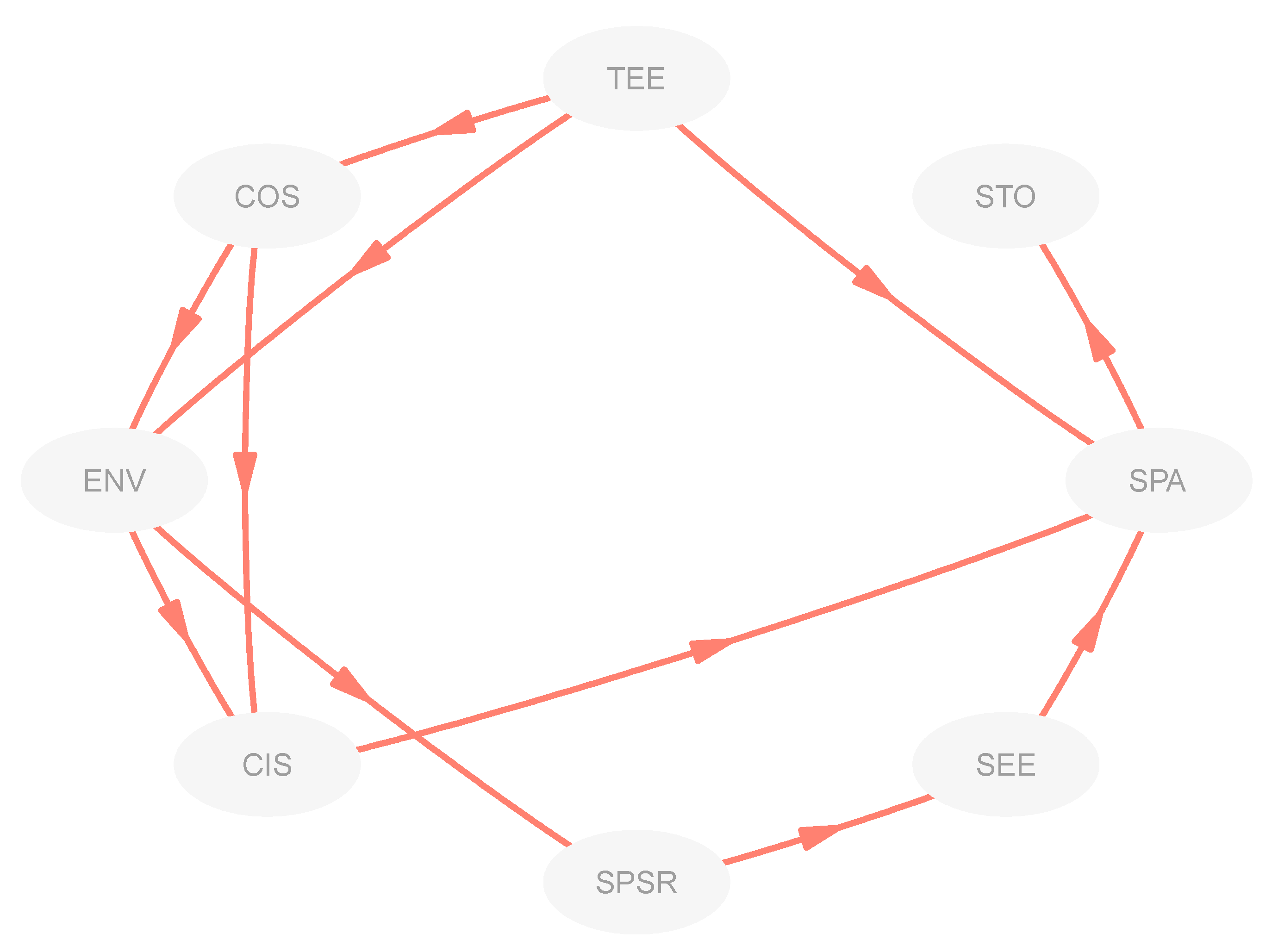

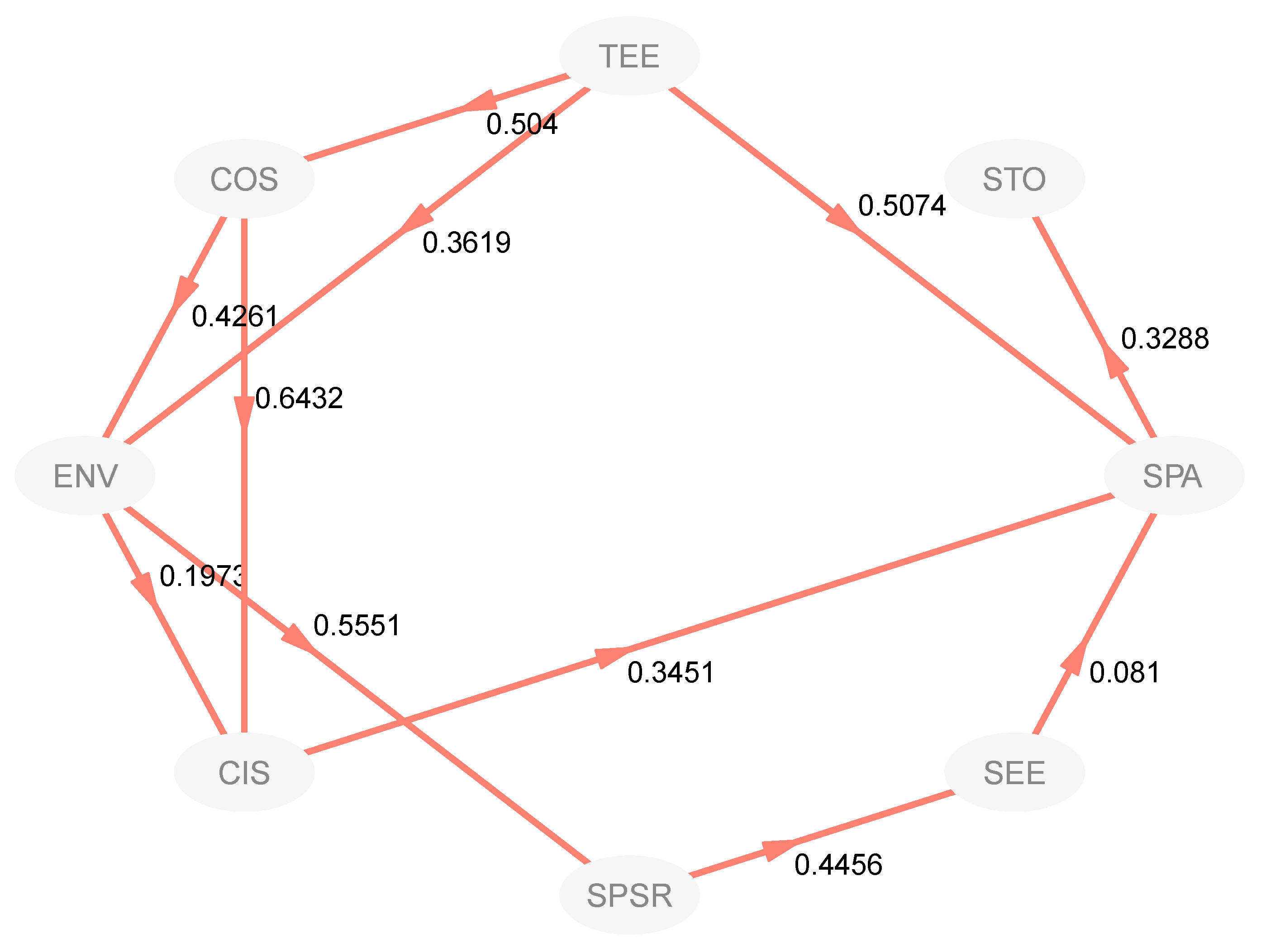

The next step was to propose a conceptual model as an improvement alternative, that is, to indicate how the components tourist ecological education (TEE), community support (COS), environment (ENV), company’s infrastructure (CIS), strategic planning and stakeholders relationships (SPSR), staff ecological education (SEE), sustainable primary activities (SPA) and sustainable tourist organization (STO), detected in the previous stages, can be related in order to achieve the transformation described in the root definition (

Figure 3).

Table 2 shows variables’ concepts and applied items. Additionally,

Table 2 offers descriptive statistics about the variables of the conceptual model.

From the SSM perspective, a hypothesis and the conceptual model definition derive precisely from the development of stages three and four. In this regard, the following general hypothesis was expressed: “A sustainable tourist organization depends on the interaction of components such as tourist ecological education, community support, environment, company’s infrastructure, strategic planning and stakeholders’ relationships, staff ecological education and sustainable primary activities.”

Accordingly, the working hypotheses fitting the conceptual model are the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Tourist ecological education is positively related to community support.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Tourist ecological education is positively related to the environment.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Tourist ecological education has a positive effect on sustainable primary activities.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Community support is positively related to the environment.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Community support has a positive effect on a company’s infrastructure.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): The environment positively affects a company’s infrastructure.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): The environment is positively related to strategic planning and stakeholders’ relationships.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): The company’s infrastructure is positively related to sustainable primary activities.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Strategic planning and stakeholders’ relationships positively influence staff ecological education.

Hypothesis 10 (H10): Staff ecological education has a positive effect on sustainable primary activities.

Hypothesis 11 (H11): Sustainable primary activities are positively related to sustainable tourist organization.

Stage 5: According to Wilson [

48,

59], the resulting construct from stages 3 and 4 can be treated as a composite and addresses unstructured situations as unidimensional problems. Based on this, PLS-PM utilization is relevant, since it treats the complexity of unstructured problems by reducing their dimensions to focus on estimating multiple relationships between blocks of variables and providing systemic conclusions [

60]. In this research, PLS-PM was used to verify if the relationships proposed in the conceptual model were congruent and fit the studied context, using the variables’ significance index. Based on this approach, the unidimensionality or internal consistency, of the conceptual model was evaluated. To this end, Hair et al. [

61] suggest testing for Dillon-Goldstein’s rho and first and second eigenvalues, in order to have evidence of consistency.

Table 3 reports on these measurements: Dillon-Goldstein’s rho values were above 0.80 in most cases. Additionally, the values of the first eigenvalue were above one and the values of the second eigenvalue were below one. These results corroborate the unidimensionality of the model and support the idea that the items correctly explain the variables to which they are related.

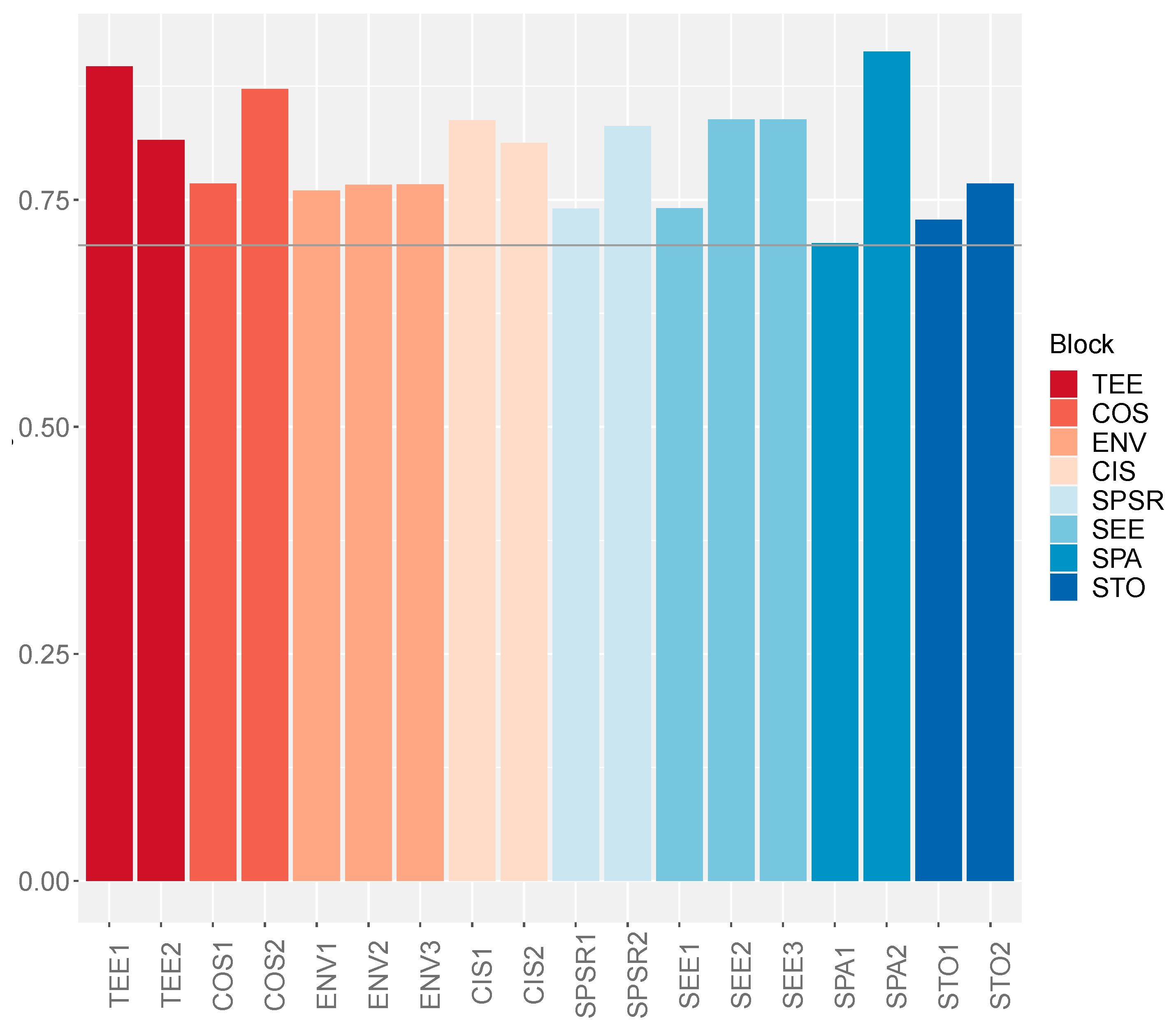

As for each item’s reliability,

Figure 4 presents the factorial loads [λ], reporting each components relative importance, which integrates each relevant variable [

58]. In this model, all items report λ greater than 0.7, exceeding the minimum 0.5 threshold and indicating commonality. Thus, each item above this threshold explains at least 50% of the variance of each variable.

In a complementary sense,

Table 4 reports discriminant validity, since the ranges of λ do not overlap with the ranges of the cross-loadings [C-λ]. This evidence ruled out the possibility that the indicators are not an appropriate proxy of their relevant variables, since λ > C-λ [

54]. This corroborates that the model derived from the SSM application fits discriminatory validity requirements, as each variable reports a more significant λ towards the corresponding variable [

61]. Under this perspective, validity exists between two variables if R

2 < AVE, that is, if the shared variance is lower than the extracted variance. Besides, to confirm the discriminatory criterion, the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) assessment suggested by Hair et al. [

61] was used and all variables values are below of the more conservative threshold of 0.85 (

Table 5).

Table 6 rectifies this condition by checking the corresponding columns. Subsequently, there is convergent validity if λ is narrow and the value of the lower limit of the loading for each variable is significant [

62].

The determination coefficients (

R2) in

Table 6 report that exogenous variables explain the variance level of each endogenous variable, providing an overview of the quality of the model. In this article, the determination coefficient (

R2) allows the evaluation of the endogenous constructs predictive power (in-sample prediction) as suggested by Felipe C.M. et al. [

64]. In this sense and according to the ranges established by Sanchez [

58], the endogenous variables environment, company’s infrastructure and sustainable primary activities have a high or substantial

R2 level, while the variables community support, strategic planning and stakeholders’ relationships and staff ecological education exhibit a moderate variance level. Additionally, this table also shows results on redundancy index (RI) (in the plspm approach proposed by Sanchez [

58], RI is the alternative measure to cross-validated redundancy index

Q2 [

64]): for most endogenous variables, it is above 0, supporting the predictive quality of the construct based on the SSM.

Figure 5 depicts the transition from stages 3 and 4 of the SSM in a path coefficients diagram indicating the effects of the proposed relationships. The paths allow us to infer that the proposed relationships make possible a sustainable organizational configuration that can meet customers’ requirements and adapt to the requirements of users, the community in which they operate and the environment. It should be noted that the COS and ENV factors are not elements that directly affect the sustainable primary operations (SPA) in tourist SMEs. However, they have an impact when the interaction of these variables is integrated with the infrastructure (CIS) and the education of the tourists (TEE), allowing the organizations under study to integrate more and more standards and sustainable practices in their operations. The models composition also highlights the need to strengthen strategic planning (SPSR) and to adopt courses of action to strengthen primary operations.

It is considered relevant that the bootstrapping analysis validated the significance of the relationships proposed in the model (see

Table 7). Together with an associated confidence interval, this analysis indicates the degree of stability or how acceptable the sample statistic is as an estimate of the population parameter [

54]. If the

perc.025 to

perc.975 confidence intervals do not contain 0, such a relationship is significant and reliable at 95%. Based on the above, it is established that since no interval contains 0, the 11 proposed hypotheses are supported. These findings suggest that addressing the factors and relationships from the model can lead tourism SMEs to organizational sustainability. However, this presents the challenge of re-arranging the organizational structure to achieve this purpose. It is also necessary to rethink the relationships and joint efforts between the local community, business owners and stakeholders, without neglecting to strengthen the capabilities of the operating units by providing sufficient autonomy to ensure organizational sustainability.

To complement the bootstrapping analysis,

Table 8 presents the

p-values: this estimation must be below 0.001 to confirm that the condition of significance is met in the model proposed in this research.

5. Discussion

The model proposed was designed under the SSM framework. This implies integrating the users vision and those involved in the problem situation to generate an alternative for improvement. Although the variables and their relationships are the information collected, they were compared with the existing literature. Considering this idea and based on the measurements obtained for the TEE variable, this research converges with the works of Chin et al. [

15], Oviedo-García et al. [

12] Campón-Cerro et al. [

11] and Hashim and Haque [

22], as they emphasize that the knowledge and education of users is a factor that affects their satisfaction, since it broadens the reference framework for evaluating the image of the company and the quality of their services. These authors also point out that sustainability is a result or consequence of the degree of client satisfaction. However, this article only partially coincides with these previous works, because although tourists’ education generates important information for organizations, it is not a factor that can shape the organizational structure to influence primary operations and steer them towards a sustainable operation. In this sense, the results obtained indicate that one of the main objectives for SMEs is to strengthen the organizational culture and primary operations (SPA), integrating into this process the results of interactions with COS, ENV and CIS. That is, based on our data, a sustainable organization and operation should not be generated reactively or under a market orientation but as a result of the understanding of the interaction of different factors, so that it is a continuous state.

The results obtained for the COS component also suggest a convergence with the contributions of Faizal et al. [

17], Rasoolimanesh et al. [

18], López et al. [

24] and Perroti et al. [

28] because it is necessary to integrate the perceptions of key actors or community representatives about the possible economic and social benefits of tourism enterprises activity. The referred works place COS as a receptor factor of the activity’s impacts and say that the information it can provide is limited. In contrast, the conceptual model proposed in this research suggests integrating the community as an element that actively participates in the processes to achieve organizational sustainability by exchanging ideas with associations that monitor tourism activity and proposing plans and initiatives that consider the benefit to the community and stakeholders. To this end, the construct proposes new relationships, which have not been considered in the literature, which are necessary to impact the operational and organizational level positively.

The evidence for the ENV variable is consistent with the research of Faizal et al. [

17] Pérez et al. [

19], Villanueva-Álvaro et al. [

20], Carrillo and Jorge [

21] and Bengtsson et al. [

23], since they emphasize that the environment affects the internal dynamics of an organization or how companies achieve their purposes. Although SMEs have organizational characteristics that restrict their structure and response capacity, this study proposes that to strengthen SPAs to impact STOs adequately, SMEs must adjust their monitoring actions, focusing on tourists, the community and the relationship with stakeholders. Focusing ENV monitoring on these components would allow organizations to make gradual but significant adjustments to the CIS and integrate information adjusted to the needs of and feed SPS; this is based on the new relationships suggested for the model that, up to this point, have not been found in the reported literature.

The results obtained for SEE allow for convergence regarding the importance of ecological education associated with staff, as indicated by authors such as Chin et al. [

15], Oviedo-García et al. [

12] and Bengtsson et al. [

23]. Nevertheless, education has been reported as a factor that impacts satisfaction, service experience, perceived quality, organization and destination competitiveness. In contrast, this study found that, on its own, this variable does not constitute a substantial component in achieving organizational sustainability. In this sense, the proposed construct proposes new relationships for the education variable, which is strongly dependent on planning (SPS) and thus is an internal component that regulates sustainable primary activities (SPA). Although authors such as Oviedo-García et al. [

12], Campón-Cerro et al. [

11], López et al. [

24], Jaya et al. [

25], Purvis et al. [

6], Martos-Pedrero et al. [

26] considered basic or primary operations to be an essential factor in achieving sustainability, it is frequently reported as an isolated but high-incidence component. Within this framework of ideas, the model based on the SSM introduces the SPA as a factor based on sustainable criteria and as a meta-systemic function that amalgamates the monitoring of critical elements of the environment, strategic planning, control and regulatory mechanisms in order to promote a sustainable tourist organization (STO).

On this basis, some implications are expressed: concerning the SPA variable, rethinking the relationships between the units in charge of operations with their management mechanisms so that they meet the demands of their immediate contexts, it is also necessary to integrate coordination functions in order to regulate their actions and avoid overlapping. This would require SMEs to strengthen communication and accountability processes with management. In this way, operations need continuous updating without neglecting sustainable practices.

Among SPSR, actions should consider strengthening SPA efforts to maintain an organizational sustainability framework. Given that SPA is a relevant component for procuring STO in this model, it is considered necessary to strengthen the capacity to generate consensus between ICS-SPSR-SPA. Human capital management intervention is necessary to comply with the above, without neglecting resource allocation, to properly implement the objectives. Additionally, actors with management functions and decision-making power must focus on promoting commitment and collaboration with sustainable practices as well as with the changes that derive from the interaction between the community and government actors. According to the model, ENV is a component that is highly related to different factors. This requires that tourist SMEs allocate resources to monitor the environment in which they operate, in order to obtain information from exogenous data that allows them to anticipate changes in the environment and generate appropriate courses of action.

6. Conclusions

Previous literature has focused on studying the causal relationship between the variables and verifying the reliability of the proposed constructs. In that sense, the design of models to deal with sustainability issues in tourism SMEs emphasizes improvement proposals based on reductionist criteria, emphasizing their particular characteristics. Although they integrate the environment variable, they tend to neglect the impact of context on crucial relationships that affect both operations and the pursuit of sustainability. This allowed us to verify the relevance of considering a systemic perspective to address the problem. Following this idea, this study considered the knowledge and experiences of those involved in the problem to propose and subsequently validate the construct. The relationships between the components that the actors believe SMEs should address in order to improve their response capacity were identified. Within this framework of ideas, the SSM-SNA and PLS-PM integration was considered suitable for proposing organizational models that differ from SMEs usual models.

From the systemic method perspective, this work attempted to highlight the idea of addressing problems in the organizational domain from a multi-methodological approach. Thus, this research tried to link the methodological tools consistently. In this sense, the first objective was fulfilled, since the SSM application allowed us to structure the problem and identify components, resulting in the proposal of a conceptual design that aimed to promote organizational sustainability without neglecting the participants perspective. The second objective was also achieved, since the use of social network analysis allowed us to identify the similarities among the participants regarding what aspects to act on to generate a process of change. The third objective of this work was to estimate and confirm the relevance of the constructs relationships through the PLS-PM. We found similarities in variables and relationships that had been reported by other authors. However, we proposed new paths that were congruent and consistent; therefore, they constitute an adequate approach to the context in which the SMEs under study operate and the possible courses of action to achieve the expressed root definition. Additionally, the statistical validation of the construct and the results obtained for each hypothesis reinforce the idea that the model can be extended to other types of organizations and even to other sectors.

Within the ideas expressed up to this point, we recognize the limitations of our proposal. Among these, we mention that the data was collected before the COVID-19 international emergency was declared, so we did not develop items that explicitly address aspects related to that. Another limitation is that the results are constrained and apply mostly in a Mexican context. However, we consider that our proposal is framed in the organizational and management domain; this limitation can be overcome by extending the study and using the proposed model in other regions or organizations.

Finally, this research contributes to the methodological domain by showing the methodological complementarity by expanding the scope of the tools used to address unstructured or diffuse problem situations in which “what, who and how” is unclear. Additionally, this research opens up a discussion and avenues to apply different approaches such as system dynamics, social network analysis, organizational cybernetics, marketing, sustainability and ethics to rethink organizational and managerial issue in the tourist industry. It is considered that the model can be used in other fields of management and even in other sectors. In conceptual matters, the proposal attempts to contribute to SME’s study using the systemic approach as an alternative method of finding a solution. Finally, in practical terms, the proposal orients the actors with management functions concerning the factors they must address to ensure organizational sustainability.