Measurement Development for Tourism Destination Business Environment and Competitive Advantages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Competitiveness and Its Applications

2.2. Tourism Competitiveness from the Perspective of the Business Environment

2.3. Composite Determinants of Tourism Destination Competitive Advantages

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Instrument

3.2. Data Collection and Samples

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

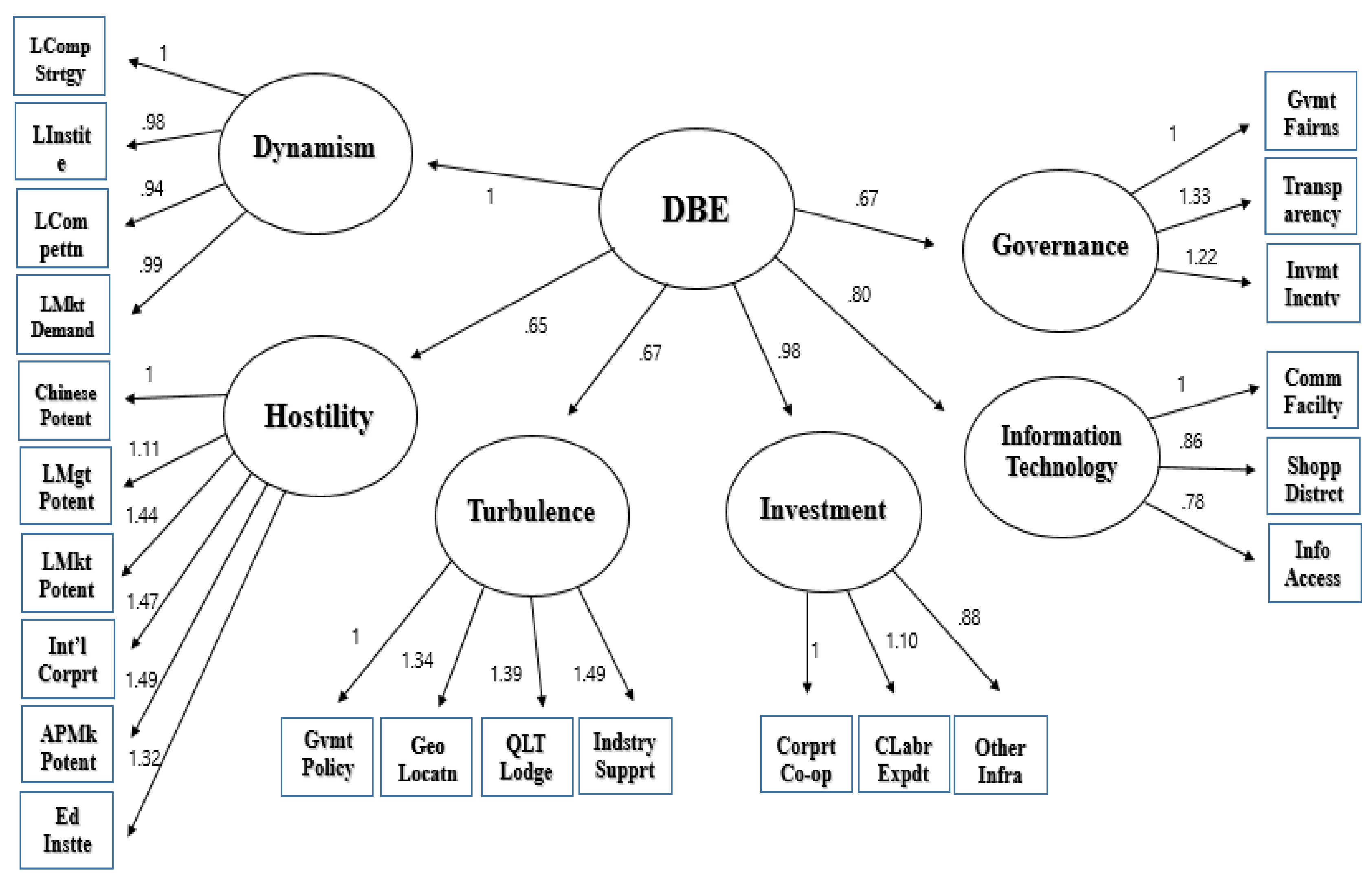

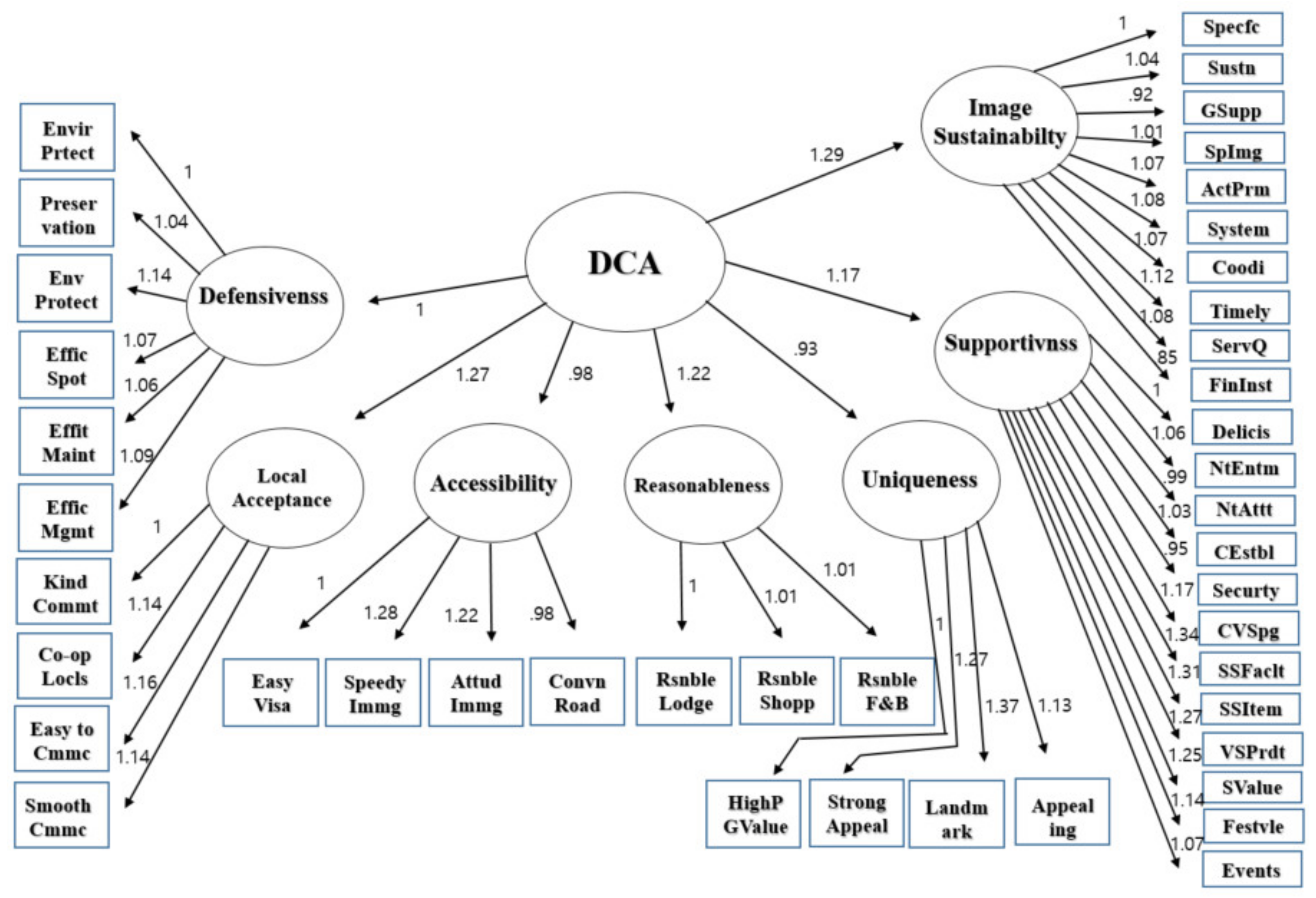

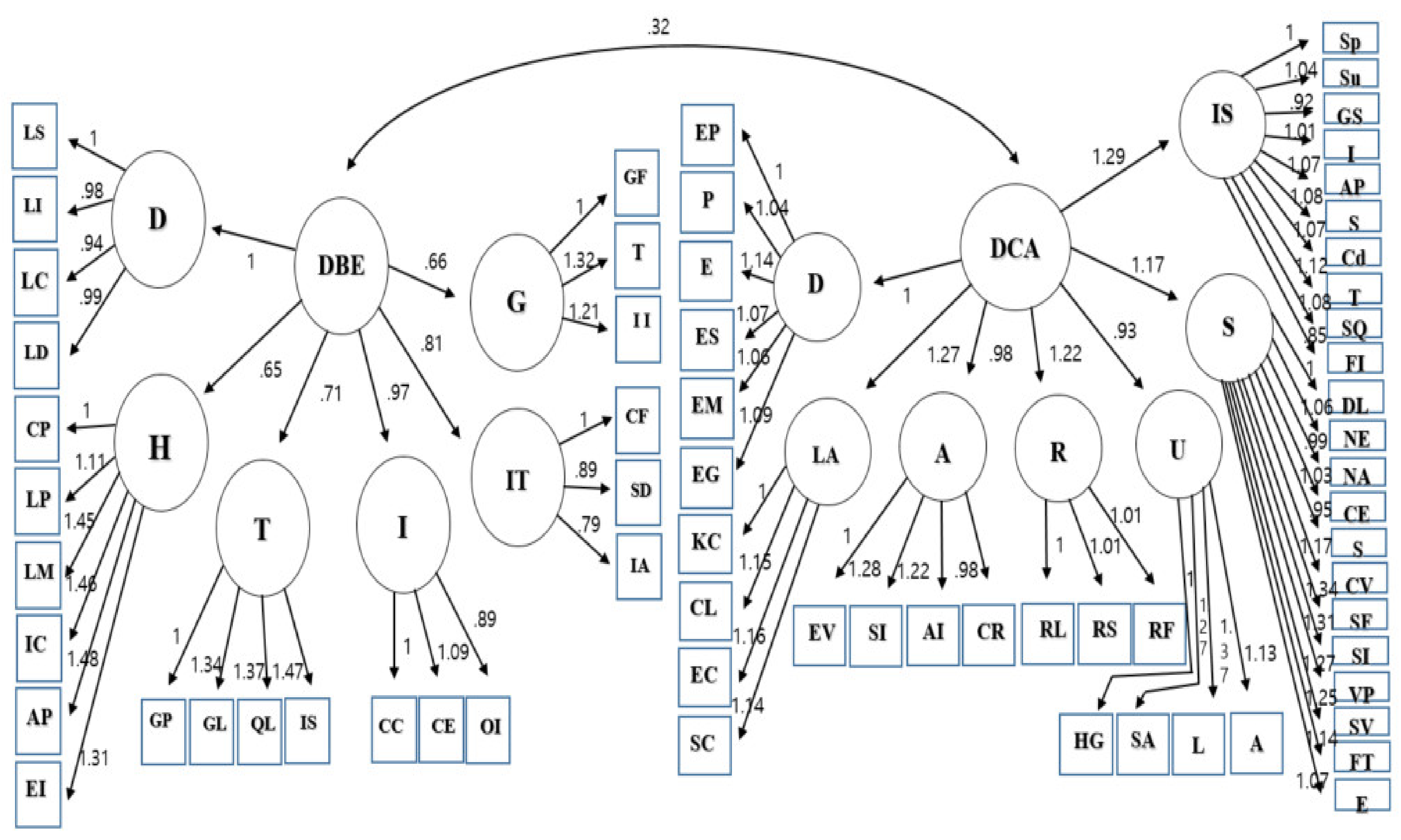

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Measurement Model Validity

5. Discussions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendola, D.; Volo, S. Building composite indicators in tourism studies: Measurements and applications in tourism destination competitiveness. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N.; Resiger, Y.; Hayes, J.P. The UAE’s tourism competitiveness: A business perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalova, E.E.; Yudina, E.V.; Bushueva, I.V.; Uhina, T.V.; Lebedev, K.A. Forming Approaches to Strategic Management and Development of Tourism and Hospitality Industry in the Regions. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2018, 2, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Semral, E.; Hallmann, K. Destination Competitiveness—A comparison of subjective and objective indicators for winter sports areas. J. Travel. Res. 2017, 56, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.P.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveler perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, competitiveness, and social prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. Competitive destination analysis in South East Asia. J. Travel. Res. 1997, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Holan, P.M.; Phillips, N. Sun, sand, and hard currency tourism in Cuba. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.M.; Tan, C.T. Assessing national competitive superiority an importance-performance matrix approach. Mark. Intell. Plann. 1992, 10, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Hallmann, K. A stakeholder perspective on policy indicators of destination competitiveness. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M.J.; Newton, J. Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The competitive advantage of nations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, R.; Snow, C. Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, H.; Jarillo, J.C. A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Dragićević, V.; Armenski, T.; Mihalič, T.; Cvelbar, L.K. Achieving destination competitiveness: An importance–performance analysis of Serbia. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2016, 19, 1309–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Crouch, G. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sánchez, Y.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. 15 Keys Strategies to Promote the Incorporation of Sustainability in Tourists’ Behaviour. In Sustainable Destination Branding and Marketing; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Croes, R. Measuring and explaining competitiveness in the context of small island destinations. J. Travel. Res. 2011, 50, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I. Destination competitiveness: An analysis of determinant attributes. J. Travel. Res. 2011, 50, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. Value as a measure of tourism performance in the era of Globalization: Conceptual considerations and empirical findings. Tour. Anal. 2005, 9, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mazanec, J.A.; Ring, A. Tourism destination competitiveness: Second thoughts on the world economic forum reports. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 725–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J. Competitiveness in mass tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.D.; Álvarez-Bassi, D.; Ramón-Cardona, J. Management of Tourist Destinations: The Expectations of Guests on eWOM Generation in Maldonado (Uruguay). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varelas, S.; Apostolopoulos, N. The Implementation of Strategic Management in Greek Hospitality Businesses in Times of Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morant-Martínez, O.; Santandreu-Mascarell, C.; Canós-Darós, L.; Millet Roig, J. Ecosystem Model Proposal in the Tourism Sector to Enhance Sustainable Competitiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Rao, P. The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: A comparison of 19 destinations. Tour Manag. 2000, 21, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. J. Travel. Res. 2000, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hartserre, A. Lessons in managerial destination competitiveness in the case of Foxwoods casino resort. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, M.J.; Frances, A.; Scott-Saavedra, E. Venezuela: The Challenge of Competitiveness; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.M. Urban Tourism: Attracting Visitors to Large Cities; Mansell: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dupeyras, A.; MacCallum, N. Indicators for Measuring Competitiveness in Tourism OECD; OECD Tourism Papers, 2013/02; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Measuring tourist destination competitiveness: Conceptual considerations and empirical findings. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 18, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Chen, J.S.; Williams, D.R. Increasing state market share through a regional positioning. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mihajlović, I. The impact of global trends at the level of macro environment dimensions on the transformation of travel intermediaries: Case of the republic of Croatia. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2014, 11, 663–674. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalič, T. Performance of environmental resources of a tourist destination. J. Travel. Res. 2013, 52, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, E.; Nash, R. A framework for island destination competitiveness—Perspectives from the island of Malta. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, D.; Avlijaš, G.; Stanić, N. Tourist perception as key indicator of destination competitiveness. TEME 2016, 2, 853–868. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kubickova, M.; Martin, D. Exploring the relationship between government and destination competitiveness: The TALC model perspective. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhan, L.; Li, S. Is sustainable development reasonable for tourism destinations? An empirical study of the relationship between environmental competitiveness and tourism growth. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Livaic, Z.; Mellor, R. Competitiveness of Australia as a tourism destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2003, 10, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.; Song, H.; Wong, K. Tourism and hotel competitiveness research. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 522–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.G. Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, O.; Kozak, M. Advancing destination competitiveness research: Comparison between tourists and service providers. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2007, 22, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Chen, W.M.; Fu, H. Corporate community involvement and Chinese rural tourist destination sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L.J. Strategic management and determinism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, W.R. Environment as an influence on managerial autonomy. Adm. Sci. Q. 1958, 2, 404–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Weber, X. Exhibition destination attractiveness–organizers’ and visitors’ perspectives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2795–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, E. Towards a model to enhance destination competitiveness: A Southern African perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2002, 10, 124–141. [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi, E.; Nash, R. A review of Crouch and Ritchie’s, Heath’s, and Dwyer and Kim’s models of tourism competitiveness. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, F.M.; Govers, R. The Asian perspective: Which international conference destinations in Asia are the most competitive? J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 1999, 1, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Opperman, M. Convention destination images: Analysis of association meeting planners’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Li, L.; Chu, G.K.T. The comparative analysis of Hong Kong as an international conference destination in Southeast Asia. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Major determinants of international tourism demand for South Korea: Inclusion of marketing variable. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Novais, M.; Ruhanen, L.; Arcodia, C. Destination competitiveness: What we know, what we know but shouldn’t and what we don’t know but should. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M.J.; Scott, E.E.; Dodwell, D. The Hong Kong Advantage; Oxford University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Go, F.; Zhang, W. Applying importance-performance analysis to Beijing as an international meeting destination. J. Travel. Res. 1997, 35, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, F.; Pine, R.; Yu, R. Hong Kong: Sustaining competitive advantage in Asia’s hotel industry. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1994, 35, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Chon, K.S. Formulating and evaluating tourism policy using importance-performance analysis. Hosp. Educ. Res. J. 1989, 13, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, B.; Oppermann, M.; Fredline, E. Destination competitiveness: An exploratory examination of South Australia’s core attractions. J. Vac. Mark. 1999, 5, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, C.E.; Swart, W.W.; Var, T. Establishing a measure of touristic attractiveness. J. Travel. Res. 1974, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Grant, J.H. Construct measurement in organizational strategy research: A critique and proposal. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagers, A.H.; Grover, V. Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: A confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Q. 1993, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, D. Social Research Methods; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ennew, C.T.; Reed, G.V.; Binks, M.R. Importance-performance analysis and the measurement of service quality. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson New International Edition; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X.; Lee, S.K.; Ahn, Y.; Kiatkawsin, K. Tourist-Perceived Quality and Loyalty Intentions towards Rural Tourism in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, L.H. A Step by Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X.; Han, H. Exploring slow city attributes in Mainland China: Tourist perceptions and behavioral intentions toward Chinese Cittaslow. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) Macro- and microenvironment and business perspective: Demographics, residents, employees, retailers, suppliers, stakeholders, transport companies, competitive trends (multinational and local firm competition), cooperation abilities, general business strategies of international and local firms, overall economic status, government policy support, investment incentives, political stability, tax regimes, legislation and regulation, strong currency, policy-making transparency. |

| (2) Sustainable drivers of tourism development: Industrial and customer demands (product and service distinctiveness, customer-oriented and niche product/service development, and leisure, etc.), market potentials (China and other Asia Pacific markets, local market demands, and long-term blueprints, etc.), international positioning, industry commitment, corporate community involvement, corporate green behaviors. |

| (3) Main drivers of tourism attractiveness and supporting resources: Physiography, climate, culture and history, special events and entertainment activities, tourism infrastructure, information supervision and communication, community institutions, accessibility, hospitality, tourism superstructure. |

| (4) Destination management and inputs: Geographic location, transportation facilities, staff skills, local managerial skills, resource stewardship, safety, costs, image, banking and financial system, finance and venture capital, carrying capital, risk estimation, human resource management, visitor administration, additional infrastructure. |

| Variable | Category | Distribution | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 123 | 65.8% |

| Female | 64 | 34.2% | |

| Age | 20s | 32 | 17.1% |

| 30s | 52 | 27.8% | |

| 40s | 55 | 29.4% | |

| 50s | 44 | 23.5% | |

| 60s and over | 4 | 2.1% | |

| Education level | Middle school or below | 12 | 6.4% |

| High school | 23 | 12.3% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 88 | 47.1% | |

| Master’s degree | 29 | 15.5% | |

| Doctorate or higher | 35 | 18.7% | |

| Marriage status | Not married | 69 | 36.9% |

| Married | 115 | 61.5% | |

| Separated | 3 | 1.6% | |

| Work position | Self-employed tourism agency manger | 18 | 9.6% |

| Chamber of commerce management | 32 | 17.1% | |

| Faulty/researcher in tourism and business fields | 54 | 28.9% | |

| Tourism administration official | 83 | 44.4% | |

| Work seniority | Less than 5 years | 55 | 29.4% |

| 5 years to 10 years | 37 | 19.8% | |

| 11 years to 15 years | 38 | 20.3% | |

| 16 years to 20 years | 32 | 17.1% | |

| More than 20 years | 25 | 13.4% |

| Variables | Dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DY | HO | TU | IN | IT | GO | |

| DY1-Local company strategy | 0.754 | 0.218 | 0.207 | 0.265 | 0.019 | 0.175 |

| DY2-Local institution | 0.765 | 0.173 | 0.097 | 0.287 | 0.090 | 0.194 |

| DY3-Local competition | 0.834 | 0.171 | 0.097 | 0.076 | 0.171 | 0.004 |

| DY4-Local market demand | 0.737 | 0.195 | 0.371 | 0.074 | 0.192 | 0.060 |

| HO1-Chinese market potential | 0.050 | 0.699 | 0.034 | −0.108 | 0.420 | 0.070 |

| HO2-Local management potential | 0.262 | 0.559 | 0.246 | −0.002 | 0.351 | 0.209 |

| HO3-Long-term market potential | 0.340 | 0.589 | 0.477 | 0.195 | −0.042 | 0.050 |

| HO4-International corporation | 0.293 | 0.731 | 0.182 | 0.289 | −0.045 | −0.004 |

| HO5-Asia Pacific market potential | 0.168 | 0.810 | 0.040 | 0.192 | 0.090 | 0.087 |

| HO6-Educational institution | 0.063 | 0.655 | 0.089 | 0.340 | 0.095 | 0.242 |

| TU1-Government policy | 0.093 | 0.026 | 0.679 | 0.000 | 0.099 | 0.431 |

| TU2-Geographic location | 0.191 | 0.090 | 0.692 | 0.172 | 0.396 | 0.146 |

| TU3-Quality lodging facility | 0.271 | 0.146 | 0.687 | 0.117 | 0.205 | 0.027 |

| TU4-Related industry support | 0.093 | 0.269 | 0.709 | 0.349 | 0.089 | 0.167 |

| IN1-Sound corporate cooperation | 0.283 | 0.251 | 0.176 | 0.722 | 0.081 | 0.126 |

| IN2-Corporate labor expenditure | 0.239 | 0.322 | 0.071 | 0.771 | 0.082 | 0.092 |

| IN3-Other social infrastructure | 0.195 | 0.040 | 0.325 | 0.696 | 0.188 | 0.158 |

| IT1-Communication facilities | 0.232 | 0.115 | 0.054 | 0.168 | 0.804 | 0.162 |

| IT2-Shopping and retail district | 0.123 | 0.079 | 0.467 | 0.186 | 0.616 | −0.178 |

| IT3-Information accessibility | 0.045 | 0.221 | 0.319 | 0.053 | 0.678 | 0.119 |

| GO1-Government fairness | 0.116 | 0.056 | 0.204 | 0.098 | −0.019 | 0.817 |

| GO2-Policy-making transparency | 0.165 | 0.331 | 0.067 | 0.231 | 0.227 | 0.629 |

| GO3-Investment Incentives | 0.175 | 0.388 | 0.241 | 0.257 | 0.187 | 0.432 |

| KMO Sampling Adequacy = 0.899, Barlett’s sphericity test: χ2 = 2258.384 (df = 276), p = 0.000 | ||||||

| Variables | Dimensions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | LA | AC | RE | UN | SU | IS | |

| DE1-Priority for environmental protection in attraction site | 0.623 | 0.039 | 0.219 | 0.011 | 0.251 | 0.300 | 0.208 |

| DE2-Efforts for preservation in pristine attractions | 0.661 | 0.161 | 0.329 | −0.078 | 0.251 | 0.171 | 0.090 |

| DE3-Prioritized involvement for environmental protection | 0.750 | 0.104 | 0.184 | 0.019 | 0.247 | 0.182 | 0.168 |

| DE4-Efficiency for cost savings in attractions and tourist spot | 0.759 | 0.132 | −0.063 | 0.237 | 0.222 | 0.182 | 0.209 |

| DE5-Efficient maintenance of attractions and tourist spot | 0.740 | 0.233 | 0.101 | 0.189 | −0.011 | 0.199 | 0.297 |

| DE6-Efficiency management and cost control in tourist spot | 0.672 | 0.159 | 0.071 | 0.082 | 0.013 | 0.146 | 0.415 |

| LA1-Local community kind to travelers | 0.167 | 0.581 | 0.352 | 0.154 | 0.159 | 0.394 | 0.238 |

| LA2-Cooperation of locals | 0.283 | 0.665 | 0.250 | 0.104 | 0.102 | 0.277 | 0.329 |

| LA3-Easy to communicate with travelers | 0.203 | 0.763 | 0.171 | 0.089 | 0.187 | 0.246 | 0.233 |

| LA4-Smooth communication between locals and travelers | 0.149 | 0.764 | 0.211 | 0.100 | 0.219 | 0.181 | 0.280 |

| AC1-Easy to get visa | 0.213 | 0.176 | 0.554 | 0.165 | 0.324 | 0.315 | 0.245 |

| AC2-Speedy immigration procedure | 0.104 | 0.159 | 0.768 | 0.091 | 0.187 | 0.256 | 0.280 |

| AC3-Good attitude of immigration and customs personnel | 0.171 | 0.217 | 0.802 | 0.096 | 0.056 | 0.208 | 0.249 |

| AC4-Conveniently and comfortably accessible to road or bridge | 0.275 | 0.336 | 0.580 | 0.062 | −0.043 | 0.273 | 0.316 |

| RE1-Reasonable and convenient lodging | 0.260 | 0.240 | 0.259 | 0.655 | 0.125 | 0.268 | 0.244 |

| RE2-Reasonable shopping | 0.149 | 0.266 | 0.206 | 0.576 | 0.151 | 0.409 | 0.301 |

| RE3-Reasonable food and beverages | 0.139 | 0.255 | 0.236 | 0.570 | 0.143 | 0.350 | 0.288 |

| UN1-High price but good value for tourist facilities | 0.234 | 0.026 | 0.125 | 0.332 | 0.513 | 0.291 | 0.230 |

| UN2-Visually strong appeal for attractions | 0.217 | 0.180 | 0.179 | 0.038 | 0.771 | 0.230 | 0.163 |

| UN3-Well-known landmark | 0.161 | 0.145 | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.789 | 0.339 | 0.243 |

| UN4-Strongly appealing attractions | 0.192 | 0.215 | 0.100 | 0.054 | 0.691 | 0.244 | 0.247 |

| SU1-Delicious local food | 0.280 | 0.137 | 0.218 | −0.087 | 0.127 | 0.632 | 0.304 |

| SU2-Good night entertainment and activity | 0.144 | 0.345 | 0.298 | −0.249 | 0.149 | 0.634 | 0.285 |

| SU3-Night attractions sightseeing and entertaining | 0.138 | 0.304 | 0.198 | −0.279 | 0.228 | 0.605 | 0.318 |

| SU4-Convenient communication establishment and service for travelers | 0.157 | 0.087 | 0.334 | 0.192 | 0.262 | 0.557 | 0.383 |

| SU5-Nice security and safety for travelers | 0.124 | 0.126 | 0.375 | 0.265 | 0.357 | 0.529 | 0.239 |

| SU6-Convenient shopping | 0.183 | 0.031 | 0.238 | 0.229 | 0.217 | 0.705 | 0.314 |

| SU7-Superior shopping facility | 0.195 | 0.090 | 0.265 | 0.142 | 0.242 | 0.789 | 0.218 |

| SU8-Superior quality to shopping items | 0.188 | 0.143 | 0.207 | 0.129 | 0.197 | 0.808 | 0.207 |

| SU9-A variety of shopping product | 0.230 | 0.141 | 0.121 | 0.154 | 0.202 | 0.805 | 0.201 |

| SU10-Shopping value | 0.206 | 0.254 | 0.113 | 0.214 | 0.170 | 0.745 | 0.178 |

| SU11-A variety of festivals tailored to a theme | 0.164 | 0.418 | −0.008 | 0.176 | 0.187 | 0.656 | 0.289 |

| SU12-A variety of events tailored to a theme | 0.138 | 0.438 | 0.034 | 0.122 | 0.161 | 0.630 | 0.282 |

| IS1-Active and sustainable tourism development for a specific theme | 0.243 | 0.182 | 0.109 | 0.061 | 0.316 | 0.290 | 0.665 |

| IS2-Active and sustainable event development for a specific theme | 0.145 | 0.223 | 0.221 | 0.089 | 0.190 | 0.361 | 0.661 |

| IS3-Consistent and sustainable support from governmental institutions | 0.380 | 0.341 | 0.129 | 0.058 | 0.181 | 0.148 | 0.603 |

| IS4-Products with a specific image | 0.275 | 0.162 | 0.119 | −0.003 | 0.367 | 0.296 | 0.678 |

| IS5-Active ads and promotion | 0.122 | 0.187 | 0.088 | 0.080 | 0.206 | 0.232 | 0.787 |

| IS6-Systematic operation in tourist site | 0.361 | 0.239 | 0.231 | 0.102 | 0.065 | 0.271 | 0.682 |

| IS7-Active product development coordination with other institutes | 0.275 | 0.169 | 0.259 | 0.128 | 0.090 | 0.175 | 0.734 |

| IS8-Efforts for timely improvement of service quality with traveler’s information | 0.178 | 0.179 | 0.291 | 0.111 | 0.125 | 0.290 | 0.723 |

| IS9-Good service quality | 0.229 | 0.185 | 0.337 | 0.201 | 0.161 | 0.405 | 0.553 |

| IS10-Convenient to use financial institutions | 0.169 | 0.113 | 0.293 | 0.169 | 0.184 | 0.374 | 0.560 |

| KMO Sampling Adequacy = 0.940; Barlett’s Sphericity test: χ2 = 7002.325 (df = 861); p = 0.000 | |||||||

| Indicators | Completely Standardized Loadings | Error Variance | t-Value (sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamism | |||

| Local company strategy | 1.000 | ||

| Local institution | 0.986 | 0.077 | 12.829 (0.000) |

| Local competition | 0.943 | 0.084 | 11.201 (0.000) |

| Local market demand | 0.985 | 0.080 | 12.328 (0.000) |

| Hostility | |||

| Chinese market potential | 1.000 | ||

| Local management potential | 1.110 | 0.168 | 6.622 (0.000) |

| Long-term market potential | 1.441 | 0.196 | 7.355 (0.000) |

| International corporation | 1.465 | 0.193 | 7.590 (0.000) |

| Asia Pacific market potential | 1.485 | 0.196 | 7.596 (0.000) |

| Educational institution | 1.316 | 0.186 | 7.064 (0.000) |

| Turbulence | |||

| Government policy | 1.000 | ||

| Geographic location | 1.343 | 0.182 | 7.388 (0.000) |

| Quality lodging facility | 1.387 | 0.192 | 7.226 (0.000) |

| Related industry support | 1.487 | 0.195 | 7.619 |

| Investment | |||

| Sound corporate cooperation | 1.000 | ||

| Corporate labor expenditure | 1.103 | 0.093 | 11.818 (0.000) |

| Other social infrastructure | 0.776 | 0.098 | 7.891 (0.000) |

| Information Technology | |||

| Communication facilities | 1.000 | ||

| Shopping and retail district | 1.331 | 0.229 | 5.802 (0.000) |

| Information accessibility | 1.220 | 0.220 | 5.547 (0.000) |

| Governance | |||

| Government fairness | 1.000 | ||

| Policy-making transparency | 0.650 | 0.104 | 6.254 (0.000) |

| Investment Incentives | 0.666 | 0.123 | 5.416 (0.000) |

| Destination Business Environment | |||

| Dynamism | 1.000 | ||

| Hostility | 0.650 | 0.104 | 6.254 (0.000) |

| Turbulence | 0.666 | 0.107 | 6.213 (0.000) |

| Investment | 0.982 | 0.121 | 8.096 (0.000) |

| Information technology | 0.795 | 0.115 | 6.886 (0.000) |

| Governance | 0.666 | 0.123 | 5.416 (0.000) |

| Fit Statistics: Chi-square = 512.173 (df = 224, p = 0.000); CFI = 0.869; TLI = 0.853; RMSEA = 0.083 | |||

| Indicators | Completely Standardized Loadings | Error Variance | t-Value (sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defensiveness | |||

| Priority for environmental protection in attraction site | 1.000 | ||

| Efforts for preservation in pristine attractions | 1.037 | 0.112 | 9.239 (0.000) |

| Prioritized involvement for environmental protection | 1.142 | 0.111 | 10.305 (0.000) |

| Efficiency for cost savings in attractions and tourist spot | 1.065 | 0.101 | 10.537 (0.000) |

| Efficient maintenance in attractions and tourist spot | 1.062 | 0.106 | 10.056 (0.000) |

| Efficiency management and cost control in tourist spot | 1.091 | 0.110 | 9.871 (0.000) |

| Local Acceptance | |||

| Local community kind to travelers | 1.000 | ||

| Cooperation of locals | 1.143 | 0.079 | 14.460 (0.000) |

| Easy to communicate with travelers | 1.158 | 0.085 | 13.599 (0.000) |

| Smooth communication between locals and travelers | 1.140 | 0.086 | 13.218 (0.000) |

| Accessibility | |||

| Easy to get visa | 1.000 | ||

| Speedy immigration procedure | 1.282 | 0.110 | 11.601 (0.000) |

| Good attitude of immigration and customs personnel | 1.215 | 0.103 | 11.819 (0.000) |

| Conveniently and comfortably accessible to road or bridge | 0.983 | 0.099 | 9.929 (0.000) |

| Reasonableness | |||

| Reasonable and convenient lodging | 1.000 | ||

| Reasonable shopping | 1.010 | 0.080 | 12.626 (0.000) |

| Reasonable food and beverages | 1.009 | 0.081 | 12.457 (0.000) |

| Uniqueness | |||

| High price but good value for tourist facilities | 1.000 | ||

| Visually strong appeal for attractions | 1.274 | 0.138 | 9.199 (0.000) |

| Well-known landmark | 1.368 | 0.143 | 9.596 (0.000) |

| Strongly appealing attractions | 1.128 | 0.127 | 8.912 (0.000) |

| Supportiveness | |||

| Delicious local food | 1.000 | ||

| Good night entertainment and activity | 1.063 | 0.103 | 10.321 (0.000) |

| Night attractions sightseeing and entertaining | 0.985 | 0.101 | 9.796 (0.000) |

| Convenient communication establishment and service for travelers | 1.026 | 0.098 | 10.511 (0.000) |

| Nice security and safety for travelers | 0.949 | 0.093 | 10.162 (0.000) |

| Convenient shopping | 1.170 | 0.097 | 12.011 (0.000) |

| Superior shopping facility | 1.337 | 0.104 | 12.904 (0.000) |

| Superior quality of shopping items | 1.314 | 0.102 | 12.898 (0.000) |

| A variety of shopping products | 1.274 | 0.102 | 12.520 (0.000) |

| Shopping value | 1.251 | 0.105 | 11.885 (0.000) |

| A variety of festivals tailored to a theme | 1.137 | 0.103 | 11.050 (0.000) |

| A variety of events tailored to a theme | 1.065 | 0.101 | 10.490 (0.000) |

| Image Sustainability | |||

| Active and sustainable tourism development for a specific theme | 1.000 | ||

| Active and sustainable event development for a specific theme | 1.036 | 0.078 | 13.251 (0.000) |

| Consistent and sustainable support from governmental institutions | 0.916 | 0.075 | 12.159 (0.000) |

| Products with a specific image | 1.006 | 0.076 | 13.295 (0.000) |

| Active ads and promotion | 1.068 | 0.081 | 13.154 (0.000) |

| Systematic operation in tourist site | 1.084 | 0.076 | 14.179 (0.000) |

| Active product development coordination with other institutes | 1.072 | 0.079 | 13.532 (0.000) |

| Efforts for timely improvement of service quality with traveler’s information | 1.122 | 0.080 | 14.029 (0.000) |

| Good service quality | 1.077 | 0.084 | 12.884 (0.000) |

| Convenient to use financial institutions | 0.846 | 0.076 | 11.202 (0.000) |

| Destination Competitive Advantages | |||

| Defensiveness | 1.000 | ||

| Local Acceptance | 1.267 | 0.163 | 7.781 (0.000) |

| Accessibility | 0.982 | 0.145 | 6.769 (0.000) |

| Reasonableness | 1.220 | 0.166 | 7.331 (0.000) |

| Uniqueness | 0.925 | 0.145 | 6.366 (0.000) |

| Supportiveness | 1.167 | 0.155 | 7.511 (0.000) |

| Image Sustainability | 1.286 | 0.157 | 8.204 (0.000) |

| Fit Statistics: Chi-square = 2198.325 (df = 815, p = 0.000); CFI = 0.815; TLI = 0.804; RMSEA = 0.096 | |||

| Indicators | Completely Standardized Loadings | Error Variance | t-Value (sig.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamism | |||

| Local company strategy | 1.00 | ||

| Local institution | 0.981 | 0.077 | 12.715 (0.000) |

| Local competition | 0.942 | 0.084 | 11.161 (0.000) |

| Local market demand | 0.994 | 0.080 | 12.430 (0.000) |

| Hostility | |||

| Chinese market potential | 1.000 | ||

| Local management potential | 1.114 | 0.168 | 6.639 (0.000) |

| Long-term market potential | 1.449 | 0.196 | 7.380 (0.000) |

| International corporation | 1.462 | 0.193 | 7.585 (0.000) |

| Asia Pacific market potential | 1.479 | 0.195 | 7.583 (0.000) |

| Educational institution | 1.307 | 0.186 | 7.040 (0.000) |

| Turbulence | |||

| Government policy | 1.000 | ||

| Geographic location | 1.344 | 0.179 | 7.507 (0.000) |

| Quality lodging facility | 1.368 | 0.188 | 7.275 (0.000) |

| Related industry support | 1.474 | 0.191 | 7.714 (0.000) |

| Investment | |||

| Sound corporate cooperation | 1.000 | ||

| Corporate labor expenditure | 1.099 | 0.094 | 11.659 (0.000) |

| Other social infrastructure | 0.892 | 0.088 | 10.106 (0.000) |

| Information Technology | |||

| Communication facilities | 1.000 | ||

| Shopping and retail district | 0.890 | 0.105 | 8.448 (0.000) |

| Information accessibility | 0.793 | 0.100 | 7.923 (0.000) |

| Governance | |||

| Government fairness | 1.000 | ||

| Policy-making transparency | 1.320 | 0.228 | 5.785 (0.000) |

| Investment Incentives | 1.206 | 0.218 | 5.531 (0.000) |

| Destination Business Environment | |||

| Dynamism | 1.000 | ||

| Hostility | 0.645 | 0.104 | 6.214 (0.000) |

| Turbulence | 0.711 | 0.111 | 6.395 (0.000) |

| Investment | 0.970 | 0.122 | 7.971 (0.000) |

| Information Technology | 0.812 | 0.116 | 6.973 (0.000) |

| Governance | 0.658 | 0.123 | 5.367 (0.000) |

| Defensiveness | |||

| Priority for environmental protection in attraction site | 1.000 | ||

| Efforts for preservation in pristine attractions | 1.036 | 0.112 | 9.267 (0.000) |

| Prioritized involvement for environmental protection | 1.141 | 0.110 | 10.344 (0.000) |

| Efficiency for cost savings in attractions and tourist spot | 1.062 | 0.101 | 10.549 (0.000) |

| Efficient maintenance in attractions and tourist spot | 1.058 | 0.105 | 10.066 (0.000) |

| Efficiency management and cost control in tourist spot | 1.090 | 0.110 | 9.908 (0.000) |

| Local Acceptance | |||

| Local community kind to travelers | 1.000 | ||

| Cooperation of locals | 1.145 | 0.079 | 14.447 (0.000) |

| Easy to communicate with travelers | 1.159 | 0.085 | 13.581 (0.000) |

| Smooth communication between locals and travelers | 1.141 | 0.086 | 13.205 (0.000) |

| Accessibility | |||

| Easy to get visa | 1.000 | ||

| Speedy immigration procedure | 1.282 | 0.111 | 11.590 (0.000) |

| Good attitude of immigration and customs personnel | 1.215 | 0.103 | 11.814 (0.000) |

| Conveniently and comfortably accessible to road or bridge | 0.984 | 0.099 | 9.932 (0.000) |

| Reasonableness | |||

| Reasonable and convenient lodging | 1.000 | ||

| Reasonable shopping | 1.005 | 0.080 | 12.548 (0.000) |

| Reasonable food and beverages | |||

| Uniqueness | |||

| High price but good value for tourist facilities | 1.000 | ||

| Visually strong appeal for attractions | 1.276 | 0.139 | 9.199 (0.000) |

| Well-known landmark | 1.368 | 0.143 | 9.587 (0.000) |

| Strongly appealing attractions | 1.128 | 0.127 | 8.905 (0.000) |

| Supportiveness | |||

| Delicious local food | 1.000 | ||

| Good night entertainment and activity | 1.063 | 0.103 | 10.322 (0.000) |

| Night attractions sightseeing and entertaining | 0.985 | 0.100 | 9.802 (0.000) |

| Convenient communication establishment and service for travelers | 1.025 | 0.098 | 10.507 (0.000) |

| Nice security and safety for travelers | 0.949 | 0.093 | 10.161 (0.000) |

| Convenient shopping | 1.170 | 0.097 | 12.011 (0.000) |

| Superior shopping facility | 1.337 | 0.104 | 12.909 (0.000) |

| Superior quality of shopping items | 1.314 | 0.102 | 12.904 (0.000) |

| A variety of shopping products | 1.274 | 0.102 | 12.527 (0.000) |

| Shopping value | 1.251 | 0.105 | 11.889 (0.000) |

| A variety of festivals tailored to a theme | 1.136 | 0.103 | 11.047 (0.000) |

| A variety of events tailored to a theme | 1.064 | 0.101 | 10.485 (0.000) |

| Image Sustainability | |||

| Active and sustainable tourism development for a specific theme | 1.000 | ||

| Active and sustainable event development for a specific theme | 1.035 | 0.078 | 13.242 (0.000) |

| Consistent and sustainable support from governmental institutions | .918 | 0.075 | 11.192 (0.000) |

| Products with a specific image | 1.007 | 0.076 | 13.323 (0.000) |

| Active ads and promotion | 1.068 | 0.081 | 13.162 (0.000) |

| Systematic operation in tourist site | 1.084 | 0.076 | 14.191 (0.000) |

| Active product development coordination with other institutes | 1.072 | 0.079 | 13.537 (0.000) |

| Efforts for timely improvement of service quality with traveler’s information | 1.121 | 0.080 | 14.027 (0.000) |

| Good service quality | 1.076 | 0.084 | 12.876 (0.000) |

| Convenient to use financial institutions | 0.845 | 0.076 | 11.192 (0.000) |

| Destination Competitive Advantages | |||

| Defensiveness | 1.000 | ||

| Local Acceptance | 1.238 | 0.157 | 7.908 (0.000) |

| Accessibility | 0.955 | 0.140 | 6.835 (0.000) |

| Reasonableness | 1.186 | 0.160 | 7.408 (0.000) |

| Uniqueness | 0.904 | 0.140 | 6.434 (0.000) |

| Supportiveness | 1.134 | 0.149 | 7.603 (0.000) |

| Image Sustainability | 1.258 | 0.151 | 8.359 (0.000) |

| DBE—DCA | 0.319 | 0.067 | 4.759 (0.000) |

| Fit Statistics: Chi-square = 4104.744 (df = 2001, p = 0.000); CFI = 0.795; TLI = 0.785; RMSEA = 0.074 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sul, H.-K.; Chi, X.; Han, H. Measurement Development for Tourism Destination Business Environment and Competitive Advantages. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208587

Sul H-K, Chi X, Han H. Measurement Development for Tourism Destination Business Environment and Competitive Advantages. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208587

Chicago/Turabian StyleSul, Hoon-Ku, Xiaoting Chi, and Heesup Han. 2020. "Measurement Development for Tourism Destination Business Environment and Competitive Advantages" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208587

APA StyleSul, H.-K., Chi, X., & Han, H. (2020). Measurement Development for Tourism Destination Business Environment and Competitive Advantages. Sustainability, 12(20), 8587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208587