Perceiving Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Case Study of a Police-Hospital Collaboration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cross-Sector Collaborations

2.2. Sustainability Transitions

2.3. Agency: A Stakeholder Salience Perspective

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The Case

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Examining Police-Hospital Collaborations through a Stakeholder Salience Lens

4.1. Perceptions of Power, Legitimacy, and Urgency: Time 1

4.1.1. Pre-Change Perceptions of Power

4.1.2. Pre-Change Perceptions of Legitimacy

4.1.3. Pre-Change Perceptions of Urgency

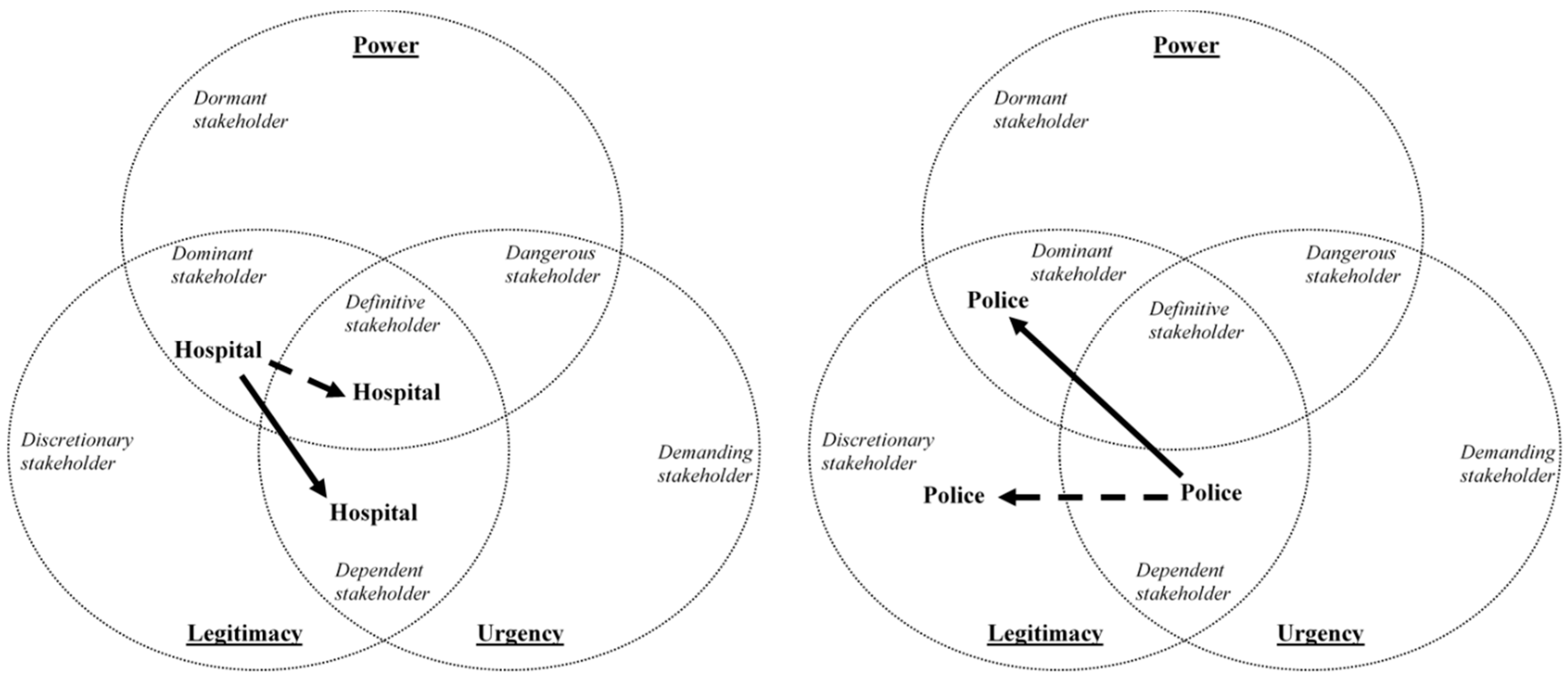

4.1.4. Summary of Pre-Change Perceptions of Agency

4.2. Perceptions of Power, Legitimacy, and Urgency: Time 2

4.2.1. Post-Change Perceptions of Power

4.2.2. Post-Change Perceptions of Legitimacy

4.2.3. Post-Change Perceptions of Urgency

4.2.4. Summary of Perceptions of Agency Post-Change

5. Changes in Agency within a Police-Hospital Collaboration over Time

5.1. Perceived Changes in Agency over Time: Power

5.1.1. Power Meso-Level Analysis

5.1.2. Power Micro-Level Analysis

“I think it’s maybe taken a little power from the Hospital because now there’s that expectation that, barring anything unforeseen, the apprehended party is supposed to be processed within a couple of hours. Ultimately, the power still remains with the Hospital, but I think the Police have a little more because there is that expectation.”(Police Constable)

“Sometimes you’ll go to a doctor and you’ll explain to the doctor what’s going on.... the doctor will have a conversation with them after they’ve talked to you, and they’re, like, no, they’re not forming them, they just need to go home and take a rest or whatever. If they aren’t going to listen to us, why are we even talking?”(Police Constable)

“It’s empowered the police... they are a little bit more likely to be more vocal on expediting themselves through the department.”(ED Resource Nurse)

“I can say it changed who has power because the police are now demanding that this is the process that we have to follow... they have more power in terms of handing the person over.”(ED Nurse)

5.2. Perceived Changes in Agency over Time: Legitimacy

5.2.1. Legitimacy Meso-Level Analysis

5.2.2. Legitimacy Micro-Level Analysis

“I think in the rush to assess the people sometimes you see people who wouldn’t normally get formed get placed on a form and this could be to do with the decline in the amount of time staff time to observe their behaviors. Going from a six-hour observation, not that it was good for the Police, down to a two-hour observation, there might be a lot more question and uncertainty whether or not the patient really needs to be here and at that point might be placed on a form and directed to psychiatry just because they are showing some symptoms.”(Hospital Resource Nurse)

“I think that... the doctors are simply forming the patient to expedite the Police to get out.”(Hospital Nurse)

5.3. Perceived Changes in Agency over Time: Urgency

5.3.1. Urgency Meso-Level Analysis

5.3.2. Urgency Micro-Level Analysis

“It’s [The intervention and escalation policy is] working because the physicians are seeing that patient quicker so instead of that patient sitting there and being sick and not knowing what’s going on, they’re being assessed. They’re being able to be medicated sooner.”(ED Nurse)

“I think they’re [doctors] recognizing that there is some time sensitivity when we have all these officers tied up. So they’ve done their due diligence and they’ve continued to, not always but for the most part, ensure that they assess the individual as soon as possible.”(Police Constable)

“They don’t have to wait in the hospital the hours that they used to wait, which was maybe between four to six hours sometimes. Now they wait two.”(ED Nurse)

“We can see there has been a large reduction in wait times for the police.”(Hospital Manager)

“There are times when we go up there and there are the longer wait times, but the hospital’s at least communicating with us a bit more... giving us a reason. Like, they could be short-staffed or they’re just buried up there... and at least knowing that, it at least gives us a bit of an explanation as to what’s going on. It helps us, especially us supervisors. If we know it’s going to be a couple of more hours, then we can redeploy people around and make things work on our end of... it makes things easier for us.”(Staff Sergeant)

“I think we’re getting better as far as recognizing a lot of these mental health crises and I think that a lot of our officers, because we deal with it so frequently, it’s allowing them... to better recognize that sort of thing.”(Police Constable)

6. Discussion

6.1. Legitimacy and Urgency Can Influence Sustainability Transitions

6.2. Organizational Context Impacts Perceptions of Agency

6.2.1. Organizational Context and Perceptions of Power

6.2.2. Organizational Context and Perceptions of Legitimacy

6.2.3. Organizational Context and Perceptions of Urgency

6.3. The Importance of Level of Analysis in Understanding Agency

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E.; Sonenshein, S. Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, F.; Etzion, D.; Gehman, J. Tackling Grand Challenges Pragmatically: Robust Action Revisited. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Entwistle, T. Does Cross-Sectoral Partnership Deliver? An Empirical Exploration of Public Service Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Equity. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, 679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The Design and Implementation of Cross-Sector Collaborations: Propositions from the Literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Thibault, L. Challenges in Multiple Cross-Sector Partnerships. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2007, 38, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Rogan, M.; Singh, J. Sustainable Cross-Sector Collaboration: Building a Global Platform for Social Impact. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, A.H.; Poole, M.S. Explaining Development and Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antadze, N.; McGowan, K.A. Moral entrepreneurship: Thinking and acting at the landscape level to foster sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U.; Vernay, A.-L.; Van Bueren, E.; Iverot, S.P. Niche entrepreneurs in urban systems integration: On the role of individuals in niche formation. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2017, 49, 1922–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, K.; Teerikangas, S.; Mikkilä, M.; Linnanen, L. Active sustainability actors: A life course approach. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 28, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.M.; Upham, P. Role of psychology in sociotechnical transitions studies: Review in relation to consumption and technology acceptance. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Dütschke, E.; Schneider, U.; Oltra, C.; Sala, R.; Lores, M.; Klapper, R.; Bögel, P. Agency and structure in a sociotechnical transition: Hydrogen fuel cells, conjunctural knowledge and structuration in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vleuten, E. Radical change and deep transitions: Lessons from Europe’s infrastructure transition 1815–2015. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 32, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, F.J.; Rotmans, J. A proposed theoretical framework for actors in transformative change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 128, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sine, W.D.; Lee, B.H. Tilting at Windmills? The Environmental Movement and the Emergence of the U.S. Wind Energy Sector. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, P. The Politics of Climate Activism in the UK: A Social Movement Analysis. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 1581–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Hekkert, M.; Jacobsson, S.; Markard, J.; Sandén, B.; Truffer, B. Technological innovation systems in contexts: Conceptualizing contextual structures and interaction dynamics. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 16, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farla, J.; Markard, J.; Raven, R.R.; Coenen, L. Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Voß, J.-P.; Grin, J. Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.; Gatignon, A. The relative value of firm and nonprofit experience: Tackling large-scale social issues across institutional contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 40, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatain, O.; Plaksenkova, E. NGOs and the creation of value in supply chains. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 40, 604–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufín, C.; Kolk, A. Bridging the institutional divide: Partnerships in subsistence markets. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ber, M.J.; Branzei, O. Towards a critical theory of value creation in cross-sector partnerships. Organization 2010, 17, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Fuller, M. Collaborative Strategic Management: Strategy Formulation and Implementation by Multi-Organizational Cross-Sector Social Partnerships. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 94, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Soda, G.; Zaheer, A. The Genesis and Dynamics of Organizational Networks. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J. Emergency medicine and police collaboration to prevent community violence. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2001, 38, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Scantlebury, A.; Booth, A.; Macbryde, J.C.; Scott, W.J.; Wright, K.; McDaid, C. Interagency collaboration models for people with mental ill health in contact with the police: A systematic scoping review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tabbaa, O.; Leach, D.; Khan, Z. Examining alliance management capabilities in cross-sector collaborative partnerships. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daymond, J.; Rooney, D. Voice in a supra-organisational and shared-power world: Challenges for voice in cross-sector collaboration. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 772–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.L.T.; Van Vliet, J.; Van Vliet, B.J.M. Niche Management and its Contribution to Regime Change: The Case of Innovation in Sanitation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2007, 19, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Geels, I.F.W. Niches in evolutionary theories of technical change. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Laak, W.; Raven, R.; Verbong, G.G. Strategic niche management for biofuels: Analysing past experiments for developing new biofuel policies. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 3213–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M. Policy design without democracy? Making democratic sense of transition management. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrase, I.; Smith, A. The (non-)politics of managing low carbon socio-technical transitions. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, T.; Paredis, E. Urban development projects catalyst for sustainable transformations: The need for entrepreneurial political leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genus, A.; Coles, A.-M. Rethinking the multi-level perspective of technological transitions. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U. Tracing discursive space: Agency and change in sustainability transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 90, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, F. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R.R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder Theory: A Libertarian Defense. Bus. Ethics Q. 2002, 12, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J. Moving beyond Dyadic Ties: A Network Theory of Stakeholder Influences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, S.; Petit, S.C. Investigating the Dynamics of Stakeholder Salience: What Happens When the Institutional Change Process Unfolds? J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 143, 485–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllykangas, P.; Kujala, J.; Lehtimäki, H. Analyzing the Essence of Stakeholder Relationships: What do we Need in Addition to Power, Legitimacy, and Urgency? J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 96, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.M.; Deephouse, D.L. A Case Study of Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization by Managers. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 75, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, B.A.; Bell, S.J.; Whitwell, G.J. Stakeholder Salience Revisited: Refining, Redefining, and Refueling an Underdeveloped Conceptual Tool. J. Bus. Ethic 2011, 102, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Gehman, J. Metatheoretical perspectives on sustainability journeys: Evolutionary, relational and durational. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 980–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.W.; Jarvis, A.; Leblanc, L.; Gravel, J.; the CTAS National Working Group (NWG). Revisions to the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale Paediatric Guidelines (PaedCTAS). CJEM 2008, 10, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvale, G.; Abelson, J.; Goering, P. Mental health service delivery in Ontario, Canada: How do policy legacies shape prospects for reform? Health Econ. Policy Law 2007, 2, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.; Sammon, S. Practice Amid Social Service Cuts and Restructuring: Working with the Contradictions of “Small Victories”. Can. Soc. Work Rev. Can. Serv. Soc. 2000, 17, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Callender, M.; Knight, L.J.; Moloney, D.; Lugli, V. Mental health street triage: Comparing experiences of delivery across three sites. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 12584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyett, N.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V. Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 23606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, A.H.; Poole, M.S. Alternative Approaches for Studying Organizational Change. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 1377–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, I.; Honig, B. A Process Model of Internal and External Legitimacy. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. Miles, M. Miles and Huberman Chapter 2. In Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business and Management; Sage Publications Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, R.; Strait, B. Straits. In Approaches to Social Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B.; Clark, S.M.; Chittipeddi, K. Symbolism and Strategic Change in Academia: The Dynamics of Sensemaking and Influence. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossoehme, D.H.; Lipstein, E. Analyzing longitudinal qualitative data: The application of trajectory and recurrent cross-sectional approaches. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hond, F.D.; De Bakker, F.G.A. Ideologically motivated activism: How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 901–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Suddaby, R.; Hinings, C.R. Theorizing Change: The Role of Professional Associations in the Transformation of Institutionalized Fields. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Armenakis, A.A. Change Readiness: A Multilevel Review. J. Manag. 2012, 39, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J.J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, J.M.; Chattopadhyay, P.; George, E.; Glick, W.H.; Ogilvie, D.; Pugliese, D. The Selective Perception of Managers Revisited. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 716–737. [Google Scholar]

- Nijstad, B.A.; Stroebe, W.; Lodewijkx, H.F. Cognitive stimulation and interference in groups: Exposure effects in an idea generation task. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, W.S.; Patterson, K.D.W. Eliciting Acceptance For “Illicit” Organizations: The Positive Implications of Stigma for MMA Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1453–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eesley, C.; Lenox, M.J. Firm responses to secondary stakeholder action. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, C.; Truffer, B. Global Innovation Systems—A conceptual framework for innovation dynamics in transnational contexts. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M.; Crumley, E.T. New Practice Creation: An Institutional Perspective on Innovation. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agle, B.R.; Mitchell, R.K.; Sonnenfeld, J.A. Who Matters to Ceos? An Investigation of Stakeholder Attributes and Salience, Corpate Performance, and Ceo Values. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exemplar Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Perceptions of Power (How is power displayed?) | |

| Doctor decides PMI’s treatment | “Once triaged, they will be moved to an assessment unit for the doctor and from there they will be put in whatever mental health unit is best suited for their needs.” (Hospital Administrator); “At times the Hospital won’t even give them anything, and it’s clear they need meds...” (Police Constable) |

| Hospital staff decides when police officers can leave | “The staff are in control of when the police will get to speak with the physician or with their patient and how long they will wait there.” (Hospital ED Nurse); “I don’t know if you’d say the administrative side or the physician side has the ultimate power… he’s got the power to make the decision: yes, I’m going to see this person now, or no, it’s not important enough, and I’m going to move on.” (Police Constable) |

| Doctor decides whether the PMI is formed | “We have the power to keep them [PMIs] for 72 hours… we can decide whether we’re going to keep you or whether we’re going to let you go.” (Hospital Psychiatrist); “The hospital does have the power to issue a form on this patient to keep them on site for the next 72 hours for further site assessment.” (Police Constable) |

| Police presence influences PMI process flow/wait time | “They can actually escalate the patient. When they’re alone with the patient, they will, and it’s been known to happen, they will escalate the patient to be seen faster or to be placed faster.” (Hospital Nurse) |

| Perceptions of Legitimacy (What legitimate role do police/health care providers perform?) | |

| Healthcare workers assess PMIs | “We have training, expertise, and a mandate to provide a comprehensive psychiatric assessment of the patient.” (Hospital MHESU Psychiatrist); “They’re the ones that have the resources available for us to turn that individual over for assessment.” (Police Sergeant) |

| Police apprehend PMIs under Mental Health Act | “The Police have the authority to apprehend someone or to detain them against their will for their own wellbeing.” (Hospital ED Physician); “The officers will apprehend them under the Metal Health Act, the party is handcuffed, searched as per our directives… to look for any object that may endanger him or us and then they’ll be transported to the nearest emergency ward with a mental health facility attached to it.” (Police Sergeant) |

| Perceptions of Urgency (Which actions are most time sensitive?) | |

| Physicians need to assess PMIs in a timely manner | “I think there is a time sensitivity out of consideration for the resources of the Police, allow them to be back on the street.” (Hospital Administrator); “If the person overdosed or they’ve taken a whole bunch of medication, then usually once you actually get to the Hospital, they are a little better… that’s really the time sensitive-stuff.” (Police Constable) |

| Physicians need to discharge PMIs in a timely manner | “The urgency is more once the decision is made that they’re not going to be admitted to get them out the door with [community] services.” (Hospital Manager); “There seems to be a lot of urgency to get them out [of the Hospital] because of limited bed space.” (Police Constable) |

| Police need to leave Hospital in a timely manner | “I believe the wait period is probably the most time sensitive… Especially overnight… Sometimes they’re sitting in emerge for 16 to 24 hours.” (Hospital Security Guard); “Waiting in the Hospital is problematic… Most of the time, I’ve got to wait eight to twelve hours just to talk to a doctor.” (Police Constable) |

| Police need to transport PMI to Hospital in a timely manner | “The Police actions are time-sensitive… if there’s no urgency to act, there’s no perceived risk to anybody, then the Police should not be apprehending.” (Hospital Mental Health Emergency Services Unit (MHESU) Manager); “I think the initial assessment done by Police at the time of the call or the time of the arrival at the scene is time sensitive. Situations with PMIs can change pretty rapidly. It can be intense.” (Police Constable) |

| Data Collection | Hospital | Police | Comparison of Responses Given by Police Versus Hospital (Meso-Level Analysis) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | |||||

| # | % | # | % | |||

| Perceptions of Power (How is power displayed?) | ||||||

| Doctor decides PMI’s treatment | Time 1 | 18 | 90% | 15 | 75% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 6 | 30% | 3 | 15% | No substantial between-group difference | |

| Hospital staff decides when police officers can leave | Time 1 | 9 | 45% | 14 | 70% | Police more likely to perceive hospital displays power in this manner |

| Time 2 | 5 | 25% | 8 | 40% | No substantial between-group difference | |

| Doctor decides whether the PMI is formed | Time 1 | 6 | 30% | 4 | 20% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 6 | 30% | 13 | 65% | Police more likely to perceive hospital displays power in this manner | |

| Police presence influences PMI process flow/wait time | Time 1 | 3 | 15% | 0 | 0% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 10 | 50% | 0 | 0% | Hospital more likely to perceive police displays power in this manner | |

| Perceptions of Legitimacy (What legitimate role do police/health care providers perform?) | ||||||

| Healthcare workers assess PMIs | Time 1 | 13 | 65% | 15 | 75% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 16 | 80% | 14 | 70% | No substantial between-group difference | |

| Police apprehend PMIs under Mental Health Act | Time 1 | 16 | 80% | 20 | 100% | Police more likely to perceive that their role is legitimate for this reason |

| Time 2 | 12 | 60% | 20 | 100% | Police more likely to perceive that their role is legitimate for this reason | |

| Perceptions of Urgency (Which actions are most time sensitive?) | ||||||

| Physicians need to assess PMIs in a timely manner | Time 1 | 9 | 45% | 1 | 5% | Hospital more likely to perceive this action is urgent |

| Time 2 | 16 | 80% | 11 | 55% | Hospital more likely to perceive this action is urgent | |

| Physicians need to discharge PMIs in a timely manner | Time 1 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 5 | 25% | 0 | 0% | Hospital more likely to perceive this action is urgent | |

| Police need to leave Hospital in a timely manner | Time 1 | 20 | 100% | 20 | 100% | No substantial between-group difference |

| Time 2 | 2 | 10% | 6 | 30% | Police are more likely to perceive this action is urgent | |

| Police need to transport PMI to Hospital in a timely manner | Time 1 | 13 | 65% | 20 | 100% | Police are more likely to perceive this action is urgent |

| Time 2 | 3 | 15% | 8 | 40% | Police are more likely to perceive this action is urgent | |

| Hospital | Police | Trajectory Analysis (Micro-Level Analysis) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Said T1 Not T2 | Said T2 Not T1 | Said T1 Not T2 | Said T2 Not T1 | ||

| Perceptions of Power | |||||

| Doctor decides PMI’s treatment | 15 (75%) | 3 (15%) | 15 (75%) | 3 (15%) | Informants from both stakeholder groups perceive hospital less likely to display power in this manner post-change |

| Hospital staff decides when police officers can leave | 6 (30%) | 2 (10%) | 9 (45%) | 3 (15%) | Informants from both stakeholder groups perceive hospital less likely to display power in this manner post-change |

| Doctor decides whether the PMI is formed | 3 (15%) | 3 (15%) | 1 (5%) | 10 (50%) | Police informants more likely to perceive that hospital displays power in this manner post-change |

| Police presence influences PMI process flow/wait time | 1 (5%) | 7 (35%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Hospital informants more likely to perceive that police displays power in this manner post-change |

| Perceptions of Legitimacy | |||||

| Healthcare workers assess PMIs | 7 (35%) | 6 (30%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) | One group of hospital informants perceive hospital has less legitimacy post-change; One group of hospital informants perceive hospital has more legitimacy post-change |

| Police apprehend PMIs under mental health act | 6 (30%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Hospital informants perceive police has less legitimacy post-change |

| Perceptions of Urgency | |||||

| Physicians need to assess PMIs in a timely manner | 3 (15%) | 10 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (50%) | Informants from both stakeholder groups perceive hospital more likely to display this form of urgency post-change |

| Physicians need to discharge PMIs in a timely manner | 0 (0%) | 5 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Hospital informants more likely to perceive that they display this form or urgency post-change |

| Police need to leave Hospital in a timely manner | 16 (80%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (70%) | 0 (0%) | Informants from both stakeholder groups less likely to perceive this action is urgent post-change |

| Police need to transport PMI to Hospital in a timely manner | 5 (25%) | 1 (5%) | 12 (60%) | 1 (5%) | Informants from both stakeholder groups less likely to perceive this action is urgent post-change |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halinski, M.; Duxbury, L. Perceiving Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Case Study of a Police-Hospital Collaboration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208402

Halinski M, Duxbury L. Perceiving Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Case Study of a Police-Hospital Collaboration. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208402

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalinski, Michael, and Linda Duxbury. 2020. "Perceiving Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Case Study of a Police-Hospital Collaboration" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208402

APA StyleHalinski, M., & Duxbury, L. (2020). Perceiving Agency in Sustainability Transitions: A Case Study of a Police-Hospital Collaboration. Sustainability, 12(20), 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208402