Abstract

The objective of this research is to identify factors affecting sustainable food consumption behavior among Malaysians. An extension of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) is used as the framework of the study. Perceived value is also added to the framework to gain an understanding of consumer’s personal factors’ effect on sustainable food consumption. This study tested eight hypotheses on sustainable food consumption behavior with empirical data from a sample of 220 adults. The regression analysis results show that social norm, perceived value, perceived consumer effectiveness, and attitude have significant impacts on intention to consumer sustainable food. Perceived availability, perceived consumer effectiveness and intention also have significant impacts on actual behavior. The findings of this study can provide certain grounds for understanding sustainable food consumption intention and behavior. Research limitations and some guidelines for further lines of research are presented. In a global context the findings of this study is important, as consumption patterns need to be changed to meet the climate challenge.

1. Introduction

Global climate change has led to the evolution of consumption patterns. Many more consumers begin to pay attention to sustainable-food consumption [1,2,3]. When the demand for sustainable products increases, market forces will make companies change their production to meet both the market demand and environmental impact reduction, including ecosystem degradation and greenhouse gas emissions. Understanding consumer behavior concerning sustainable-food consumption is important for the survival of a business.

Sustainable food is an emerging concept and has provided a quite varied arrangement of policy suggestions and definitions [4,5,6]. This is according to Gorgitano and Sodano’s [4] definition, that sustainable food should “meet safety, political and environmental requirements, such as safe, healthy, and nutritious diets for everyone; viable livelihood for farmers, processors, and retailers; animal welfare; environment protection; biodiversity safeguard; energy saving; minimum waste”. Many industrial ecologists and economists have examined the association between sustainability and dietary habits, developed sound conceptual models, and conducted empirical studies that explain the environmental values of diets and examines alternative diets concerning the various measure of sustainability [7]. For example, Gelinder et al. [8] in their study on students’ choices of sustainable food in Sweden addressed sustainability issues have been compulsory to include in school syllabus and provided the guidelines on how to make choices of sustainable food. Sidali et al. [9] collected data from three industrialized countries, Germany, United States and Switzerland, and three emerging countries, Brazil, China, and India. Their study highlighted that the expectations of sustainable food consists of five constructs: innovation, terroir, health-related aspects, naturalness, and ethical attributes. Another study [10] conducted in Belgium examined the effects of social norms, values, perceived consumer effectiveness, certainty, perceived availability, and involvement in consumers’ attitudes towards sustainable food. However, research that focused on factors affecting sustainable food consumption is still inadequate. None of the studies were conducted in the Malaysian context. Research from one country to another cannot be generalized as the one to another country differ culturally and economically. Thus, our study focuses on exploring the factors that influence consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable-food products in Malaysia.

The research question that may be raised in the study is what factors dominate the consumption of sustainable food. This question has been investigated in the literature, but further investigation will assist the development of knowledge in the field. It is required to describe the reasons for this behavior [11]. Evaluating the obstructions that exist between behavior and attitude as well as understanding the way consumers decide to consume sustainable food produces is a part of the procedure of decreasing carbon footprints and in the long run [12,13,14]. A better theoretical consideration that may guide to new information for policy creators. Therefore, the main aim of this research is to use an extension of the theory of planned behavior to explore the factors affecting sustainable food consumption behavior in Malaysia.

As to the structure of the research, the subsequent section illustrates the theoretical background of the study, and the third section proposes the research hypotheses. The fourth introduces the research methods used in the study. The fifth section shows the research results, followed by the sixth section addressing discussions on the research findings. The final section gives research conclusions.

2. Theoretical Framework

To explain sustainability-related behavior, several theories have been proposed in the literature [15]. For example, the value-belief-norm (VBN) model was developed by Stern et al. [16] to clarify the effect of human values on behavior in the context of environmentalist. In a causal chain, this theory postulates the association between behaviors, values, beliefs, and norms [16,17]. Schwartz [18,19,20] explained values in a multidimensional concept. The VBN model has been used in several studies [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Among several theories proposed in the research, the most widely usage theory is the theory of planned behavior (TPB) used to explain consumer behavior. Therefore, this study will use the TPB to examine what factors impacting consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable-food products.

According to the scholars, the TPB (theory of planned behavior) can explain and predict a wide variety of human behaviors across a variety of settings [27,28]. Based on available information and careful consideration this theory was developed to framework deliberative decision making and conscious, grounded in the social cognitive psychology literature. The model assumes that individual can control a significant amount of their behavior; thus, by identifying intention of individual’s to perform a behavior, actual behavior can be predicted [28]. Intentions refer to an individual’s motivation, to try hard to endorse the behavior and willingness to employ effort [27].

TPB proposes that the likelihood of occurring a behavior depends on an individual’s intention to engage in that behavior, while individual’s attitudes play a crucial role to develop their intentions [27,28]. Perceived desirability of the eventual outcome of an action (personal desirability), the acceptability of the outcomes by the reference group (social norms), and the feasibility of the behavior (perceived behavioral control) are some important attitudes that affect intentions in TPB [27,28].

TPB is the extension of the theory of reasoned action (TRA), which can evaluate and assess several complicated traits of human behavior [29]. TRA clarifies how individual’s certain behavioral traits and reactions influence them to adopt or rejects of certain behavior. TRA also defines a certain attitude of consumer behavior when it comes to purchasing or choosing a certain product. In other words, it provides reason and explanation of why certain consumers select a certain type of product [30]. TPB complements the behavioral control to two main constructs of TRA which are norms of attitude and subjective norms [27].

Extant studies on social psychology and consumption have provided empirical support to TPB has been supported by [27,28,29,30,31]. According to Thomson et al. [32] meta-analysis technique, the variable attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control can explain 40–50% of the variance in individual’s intention, which further explains 19–38% of the variance in behavior. Various research on food choices by consumer have used TPB as their underpinning theory and found empirical support [33,34,35]. Honkanen et al. [36] argued that TPB is an important model for studies in the context of food.

Other researchers have found the theoretical framework of TPB to be very important in food consumption-related behavior [37,38]. There are more than 600 studies that have provided empirical evidence of the TPB framework in the last decades [39]. For example, a study by Karajin and Iris [35] studied on halal meat buying intention and found that attitude, social norm, and perceived behavioral control had significant influences on intention in France. In the organic food buying context [33,40,41], and online purchasing behavior [42,43,44,45,46,47,48] also researchers found support of TPB. Although TPB has been used in food-consumption related studies, only a few studies [10] have emphasized the theoretical framework of TPB model to investigate sustainable food consumption behavior of consumers. Vermeir and Verbeke [10] examined the effects of social norms, values, perceived consumer effectiveness, certainty, perceived availability, and involvement on consumers’ attitudes towards sustainable food. There is a dearth of research which applies the factors of TPB model to explain sustainable food consumption behavior of consumers.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

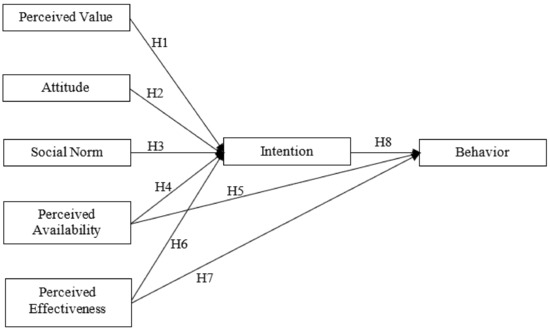

The TPB was used as the based model for this research, as shown in Figure 1. One new construct, perceived value, is added to the model, as perceived value may influence behavioral intention [49,50,51].

Figure 1.

The diagram of the conceptual framework.

Sustainable food consumption intention precedes the actual purchasing behavior. Intention reflects future behavior. Perceived value, attitude and social norm are postulated to have direct and positive relationships with intention. Perceived availability and perceived consumer effectiveness are two constructs representing perceived behavioral control, and will examine the positive relationship with intention and behavior, whereas behavioral intention has a positive and direct relationship with behavior.

Perceived value refers to the consumer’s overall evaluation regarding the net benefit of a good or service that they receive [52,53]. Zeithaml [54] identified perceived value is an important antecedent of buying intention. Other researchers also revealed that customers’ perceived value can significantly influence their intention to buy [49,50,51,55,56,57]. Thus, based on the above arguments the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1(H1):

There is a positive relationship between perceived value and the intention of sustainable food consumption.

Attitude is a very important factors in influencing consumers’ purchasing behaviors [27,58,59]. Moreover, attitude is considered as a leading factor for intention to sustainable or environmentally friendly foods [42]. Several researchers have found a significant relationship between attitude and intention to sustainable food consumption. Among them, Vermeir and Verbeke [10] and de Barcellos et al. [12] shed light on the way attitude influence intention to consume sustainable food. Therefore, the second hypothesis of this study is:

Hypothesis 2(H2):

There is a positive relationship between the attitude of consumers and the intention of sustainable food consumption.

As mentioned by many scholars, social norm or subjective norm is another factor in the TPB model [12,27,60]. As mentioned by Baker et al [61], social norm is a very important predictor for intention to sustainable food consumption. Ruiz de Maya et al. [62] stated that social norm has a very close relationship with the culture of people. Furthermore, Vermeir and Verbeke [63] stated that sometimes even consumers who have not had a positive attitude towards purchasing organic-food will do so because of the effect of social norms. Consumers will have stronger intentions toward purchasing sustainable and organic foods when they are motivated by social norms. The relationship between social norm and intention to sustainable food consumption is direct [27]. Thus, the third hypothesis of the framework is:

Hypothesis 3(H3):

There is a positive relationship between the social norm of consumers and the intention of sustainable food consumption.

Perceived availability refers to the extent that consumers feel that sustainable products are easily accessible [27]. As mentioned by so many researchers who used the TPB model in their studies, perceived availability is a very crucial factor in shaping consumers’ intention toward purchasing foods and particularly the sustainable one [27,60,64,65,66]. It has been mentioned by some scholars that perceived availability has a very crucial effect on the purchase of consumer goods; in some cases, it can even be a barrier for their purchase if there is no availability of products [63,67]. In other words, perceived availability can effect on consumers’ intention of sustainable-food consumption, consequently, their behavior [10,63]. Moreover, it can directly affect the behavior of consumers. So, it can be concluded that:

Hypothesis 4(H4):

There is a positive relationship between perceived availability and the intention of sustainable food consumption.

Hypothesis 5(H5):

There is a positive relationship between perceived availability and the behavior of sustainable food consumption.

Perceived effectiveness, as mentioned by Ajzen [27], Persson [60], Vermeir, and Verbeke [63], refers to how positively or negatively a consumer thinks of his or her actions. Arvola et al. [68] stated that consumers need to feel good about their actions, and they need to be aware of the fact that their actions do bring about a change in the food cycle; otherwise, they would feel demotivated and reluctant to make a change. As also mentioned by Sparks and Shepherd [33], it is strongly believed that perceived effectiveness would eventually increase food consumption behavior. Roberts [57] also believes that perceived effectiveness is a controlling factor that motivates consumers to have a higher intention to the consumption of sustainable products and at the end of the behavior of sustainable food consumption. Vermeir and Verbeke [10] stated that perceived effectiveness is an important factor which can significantly influence consumers’ intention to buy sustainable food products. Persson [60] stated that behavioral controls which mean perceived consumer availability and effectiveness possess a direct relationship with consumers’ intention and behavior. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6(H6):

There is a positive relationship between perceived effectiveness and the intention of sustainable food consumption.

Hypothesis 7(H7):

There is a positive relationship between perceived effectiveness and the behavior of sustainable food consumption.

Researchers identified a strong association between intention and actual behavior [28]. In this study, the intention is considered as one of the variables which influence behavior. According to the TPB model, intention is the most important predictor of human behavior [27,58,64]. The intention is the item which leads to the behavior of food consumption. Researchers like Kim and Hunter [69] also identified intention as a predictor of behavior. Vermeir and Verbeke [63] stated in their study how a strong intention can lead to the action of behavior. Persson [60] argued that the “direct relationship between intention and behavior” is much stronger than the relationships of other variables to intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 8(H8):

There is a positive relationship between intention to sustainable food consumption and the behavior of sustainable food consumption.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

In this study, a primary data collection method was employed to gathered the required data through the questionnaire survey. The respondents were gathered from the Klang Valley area in Malaysia. There were 300 questionnaires were distributed personally to the respondents in two big shopping malls and 231 were returned back where only 220 are usable. Female were the highest respondents (54.1 percent), and whereas the highest of age group of 20 and 25 (55.9 percent). The highest contributors in this research are Chinese group of the total respondents (51.81 percent) and the next group of respondents were represented by Malays (31.36 percent). Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile.

4.2. Measures

To develop the questionnaire, the questions for this study were adopted and adapted from the previous researches [10,60,70]. The demographic information of the respondents, such as race, gender and age were asked at first in the questionnaire. Then the questions measuring the sustainable food consumption intention and behavior, as well as factors that influence sustainable food consumption intention, were asked by using a Likert-scale ranging from “1= strongly disagree” to “6 = strongly agree”.

4.3. Common Method Bias

Harman’s single-factor analysis widely used to test common method bias [71]. Therefore, the common method bias in the study was tested by using Harman’s method. Employing the KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) technique, the results showed that the values were above 0.5 in the diagonal matrix and the KMO value was 0.824. Additionally, an un-rotated factor analysis method was used and confirmed that all factors were loaded separately, and no single factor showed a value of more than 50%. There are five factors loaded, and the first factor showed a value of 33.237. While common method bias would exist if a single factor shows a variance higher than 50 [71,72], the results revealed that there is no common method bias exist in our study.

4.4. Reliability

In this study the Cronbach’s alpha was used to verify the internal reliability of the items [73]. The Cronbach’s alpha for perceived value was 0.902, attitude was 0.839, followed by social norm, which was 0.851, and perceived availability (0.752), perceived effectiveness (0.797), behavioral intention (0.876), and behavior (0.788). The result indicates a reliable consistency among the variables since all the constructs Cronbach’s alpha are avove the threshold value of 0.7 [74].

4.5. Content Validity Test

Content validity denotes whether the instrument is adequate to measure the variables under research. The function of content validity is judgmental and subjective [73]. Extensive literature survey were done before developing the questionnaire and taken opinions from experts in this area and thus we conclude that the content is valid.

4.6. Construct Validity Test

Construct validity represents the extent to which the items in a scale measure the same construct. To examine underlying constructs and identify the association among interval-scaled based questions regarding the intention of sustainable food consumption an exploratory factor analysis was tested. Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization and principal axis factors were considered. Varimax rotation enabled interpretability. To test the suitability of factor analysis usage, The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) was first calculated.

The factors have been retained those eigenvalues was more than 1.0. Factors were dropped and considered insignificant in which the eigenvalues were less than 1.0. There were five factors found the eigenvalues more than 1.0, which are shown in Table 2. A total of 61.33% of the variance explained of these five factors. Under the five conditions for sustainable food consumption considered in this study, the combined results of factor analysis indicate that all items are loaded properly on their expected factors.

Table 2.

Item loading and Cronbach’s Alpha.

4.7. Multi-collinearity and Normality of Data

There were 220 respondents were used for this study which is considered as large and thus, the central limit theorem could be applied, and therefore the normality of the data is not questionable. Two main approaches namely tolerance test and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were utilized to determine the presence of multicollinearity among independent variables [75]. The results presented in Table 3 shows that all the variables tolerance levels are below than 0.01, and the VIF values are less than 10. The results thus indicate that there are no multicollinearity issues in this study.

Table 3.

Test of Collinearity.

5. Hypotheses Testing Results

Multiple regression results are shown in Table 4 that were used to test the hypotheses. To test the hypotheses, this study followed the guidelines suggested by Hair et al. [74] where intention and behavior are considered as the dependent variables. The results showed that except for hypothesis H4, all other hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, H7, and H8 were found to be significant in the prediction model. The results provide support for hypotheses that there was significant effect of perceived value on intention (β = 0.277; p < 0.001), attitude on intention (β = 0.148; p < 0.006), the social norm on intention (β = 0.292; p < 0.001), perceived consumer effectiveness on intention (β = 0.260; p < 0.001), perceived availability on behavior (β = 0.493; p < 0.001), perceived effectiveness on behavior (β = 0.423; p < 0.001), and intention on behavior (β = 0.833; p < 0.001) as predicted.

Table 4.

Results of Hypotheses Testing.

In summary, our study found that except perceived availability, all other exogenous variables such as perceived value, attitude, the social norm and perceived consumer effectiveness have a significant relationship with behavioral intention. Moreover, perceived availability, perceived consumer effectiveness and intention are important predictors of consumers’ sustainable food consumption behavior. The results are in line with previous studies.

6. Discussions

Our study attempts to determine the factors that can influence consumers’ intention and behavior in sustainable food consumption context. The regression analysis results revealed that the perceived value can increase consumers’ sustainable food consumption intention. This finding is in line with the literature presented in this study. For instance, Brady and Robertson [56], Eggert and Ulaga [49], Tam [50], and Gounaris et al. [51] argued that perceived values have a strong effect on the perception of consumers regarding the intention of food consumption. Perceived values do play a crucial role when it comes to shaping consumers’ behavior in the sustainable food market [76].

The regression results show that there is a positive relationship between the attitude of consumers and their perception and sustainable food consumption intention. The findings do suggest a strong effect of the variable and the positive effect of attitude is present within this framework. These findings are similar to the findings of [63,68,77,78]. Persson [60] asserted that the role of attitude on sustainable consumption of food is inevitable and the attitude of people shapes their perception and belief system towards what they consume. These cues could be influenced and fluctuated by a positive or negative attitude towards certain food production. Based on these findings, it could be suggested that the effect of attitude on sustainable food consumption is evident.

The regression analysis results suggest that social norms can positively influence sustainable food consumption intention. The coefficient beta found in this construct is the strongest among all the variables in this study towards sustainable food consumption. This suggests that social norms have the most effective and crucial effect on food consumption in comparison to all the other variables. Other scholars have found the effect of social norms just as significant. For instance, Robinson and Smith [28], Vartanian et al. [79], Beck and Ajzen [80], and Engels et al. [81] all suggest that the social beliefs of a group of people are extreme determinants when it comes to selecting food categories. Social norms might differ among various age groups of society, as certain groups create and validate their belief system. Therefore, the findings of this study confirm social norms have a positive relationship with sustainable food consumption.

The results also reveal that perceived availability has no direct and significant effect on the intention to sustainable food consumption intention. This result contradicts that of prior studies which found a significant relationship between perceived availability and sustainable food consumption intention [12,27,29]. It should be noted that the rejection of the hypothesis only projects the related findings of this study, and the function of this particular variable might function differently when it is influenced by other variables or certain instigating factors.

The findings of the regression analysis strongly point to a positive relationship between consumer effectiveness and sustainable food consumption intention. According to the findings, it could be concluded that perceived consumer effectiveness has a positive effect on consumers’ intention to consume sustainable food. Following these significant findings, Sparks and Shepherd [34] and Arvola et al. [68] have confirmed these findings, and added that, if consumers are aware of their role in the modification of certain cues of intention towards sustainable food consumption, then they might react positively towards preserving it. Arvola et al. [68] argued that the role of consumers in preserving and promoting sustainable food consumption could not be forsaken, for consumers would come to the real terms of their efficiency in promoting sustainable food consumption when they are aware of their roles.

Strong reasons have been achieved to support the positive relationship of “perceived availability and perceived consumer effectiveness” over the behavior of sustainable food consumption. It could therefore, be inferred that these two variables do impose a strong effect on shaping the behavior of consumers towards sustainable food for “perceived availability and perceived consumer effectiveness”.

Perceived availability has a stronger effect on shaping the behavior of consumers. It could be suggested that the imposed influence of perceived availability is stronger than the induced effect of consumer effectiveness, and nonetheless, it could also be suggested that perceived availability does alter the behavior of consumers. These findings comply with the work of other scholars [27,63,67,82,83], where they have declared that, when a product is easier to find for consumers, they might consider turning towards that particular product, and therefore, it could change their mindset and perception, and eventually their behavior about how they consume and purchase certain products.

Furthermore, the effect of perceived effectiveness is also grand on shaping the behavior of consumers towards consuming food products. This finding has also been confirmed by some other scholars, considering one’s self as being an effective factor in making a difference; their behavior could be significantly altered towards food consumption; in other words, when consumers see their role in sustainable consumption, their attitude is likely to be altered and manipulated on the same grounds.

The findings of our research indicate that perceived availability and effectiveness do impose a positive role on the behavior of food consumption by consumers and therefore, the two hypotheses could be adopted for this study. The regression analysis implies a positive and strong relationship between intention and behavior components. Results suggest that intention towards the behavior formation of sustainable food consumption is relatively positive. The findings of this study would match the existing studies throughout the literature [27,28,60,84], which suggested that intention and behavior are complements where one would better define the other. The intention would be considered as the main driver of behavior, where one sets the very fundamental modification of the other. In other words, the intention would shape the behavior of consumers towards the consumption or non-consumption of food. Furthermore, Vermeir and Verbeke [63] also stated that intention and behavior are closely related, and they merge the very nature of each other. In other words, the intention has the potential to form or deform the functionality of behavior of food consumption. Hence, it could be suggested that consumer’s intention to sustainable food consumption can positively effect on their food consumption behavior.

7. Conclusions

This study looked into the main components and constructs that might affect the intention and behavior towards the consumption of sustainable food in Malaysia. Among all the variables except perceived availability, all other variables have been proven to impose significant effects on the perception of behavior and intention towards sustainable food consumption. The regression analysis conducted in this study clearly illustrated that the variable which induces the strongest effect on the intention factor was perceived consumer effectiveness, and the least strong was the attitude component.

From a managerial point of view, our study aims to contribute to a better decision-making process. Managers should keep track of certain changes that are imposed on the behavior and intention of consumers. On another note is that the social norms are crucial to influence consumer’s intention to sustainable food consumption. The managers can take this finding as a clear indication of the need to produce food sustainably in the future. During this sustainable development era, the notion of sustainable food consumption can be widespread and could potentially shape social norms globally. Therefore, a snowball effect is expected by sustainable-food production to fulfil the rising demand for sustainable food consumption. Furthermore, the findings of this study achieved, to some extent, clarity with regard to how certain dominators cannot be the determinants of behavior and intention. This study looked at important factors that might keep influencing consumers’ intention and behavior of sustainable-food consumption. The contribution of the findings of this study helps to evolve a more justified and consistent view of the behavior and the possible factors which might influence sustainable food consumption.

The study was limited to only a particular area in Malaysia. Further study can be conducted in other countries. The study only used the regression analysis to test the proposed research hypotheses. Further study may use the structural equation modeling to test more comprehensive relationships regarding the relationship between these variables. The present study employed the extended theory of TPB model to explore sustainable food consumption behavior among Malaysians. Further study may use other theories, such as a “value-belief-norm (VBN) model” or an “attitude-behavior-context (ABC) model”, to examine sustainable food consumption behavior among Malaysians.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.A., M.A. and C.-Y.L.; methodology, S.S.A.; software, N.A.O.; validation, S.S.A., Y.-H.H. and N.A.O.; resources, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.A., M.A., Y.-H.H. and C.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.S.A., Y.-H.H. and C.-Y.L.; project administration, S.S.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Yayasan Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS grant no. 015LC0-254.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Towards a conceptual framework for sustainable business models in the food & beverage industry: The case of German wineries. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubiello, F.N.; Fischer, G.N. Reducing climate change impacts on agriculture: Global and regional effects of mitigation, 2000–2080. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chan. 2007, 74, 1030–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgitano, M.T.; Sodano, V. Sustainable food consumption: Concept and policies. Calitatea 2014, 15, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Commission. Sustainability Implications of the Little Red Tractor Scheme; SDC: London, UK, 2005; Available online: http://www.sd-commission.org.uk/publications.php?id=195 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Sustainable Development Commission. Setting the Table: Advice to Government on Priority Elements of Sustainable Diet; SDC: London, UK, 2009; Available online: http://www.sd-commission.org.uk/publications.php?id=1033 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Duchin, F. Sustainable consumption of food. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinder, L.; Hjälmeskog, K.; Lidar, M. Sustainable food choices? A study of students’ actions in a home and consumer studies classroom. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Spiller, A.; von Meyer-Hofer, M. Consumer expectation regarding sustainable food: Insights from developed and emerging markets. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “Attitude-Behavioural Intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Barcellos, M.D.; Krystallis, A.; DE Melo Saab, M.S.; Kügler, J.O.; Grunert, K.G. Investigating the gap between citizens’ sustainability attitudes and food purchasing behaviour: Empirical evidence from Brazilian pork consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Climate change and dietary choices—How can emissions of greenhouse gases from food consumption be reduced? Food Policy 1998, 23, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Gregory, P.J. Climate change and sustainable food production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufele, I.; Uamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions, preferences and willingness-to-pay for wine with sustainability characteristics: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof1, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Elicitation of moral obligation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 15, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value priorities and behaviour: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. Psychol. Values 1996, 8, 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. A general measure of ecological behaviour. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.S.; Yap, S.-F. Pro-environmental behaviours and value-belief-norm theory: Assessing unobserved heterogeneity of two ethnic groups. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Faulin, J. An extended planned behavior model to explain the willingness to pay to reduce noise pollution in road transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtissem, M.H. Application of value beliefs norms theory to energy conservation behavior. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 3, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.; Smith, C. Psychosocial and demographic variables associated with consumer intention to purchase sustainably produced foods as defined by the Midwest Food Alliance. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Understanding the determinants of consumer composting behavior. J. Soc. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 27, 602–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.E.; Hazinz, N.; Alekas, P.J. Attitude and food choice behavior. Br. Food J. 1994, 96, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: Assesing the role of identification with green consumerism. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sparks, P. The theory of planned behavior and health behaviors. In Predicting Health Behavior; Conner, M., Norman, P., Eds.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1996; pp. 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Karajin, B.; Iris, V. Determinants of halal meat consumption in France. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 367–386. [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen, P.; Olsen, S.O.; Verplanken, B. Intention to consume seafood- the importance of habit. Appetite 2005, 45, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R.; Frewer, L.J. Assessing and structuring attitudes towards the use of gene technology in food production: The role of ethical obligation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 16, 67–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Fairwheather, J.; Campbell, H. New Zealand farmer and grower intentions to use genetic engineering technology and organic methods. In Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit Report No. 243; Lincoln University: Canterbury, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, E.S. The Theory of Planned Behavior applied to continuing education for mental health professionals. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 1324–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, K.M.; Anne, M.; Hustri, U.K. Attitude towards organic food among Swedish consumers. Br. Food J. 2001, 103, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Anssi, T.; Sanna, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar]

- George, J.F. Influence on the intent to make internet purchase. Internet Res. 2002, 12, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.F. The theory of planned behavior and internet purchasing. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battarcherjee, A. Individual trust in online firms: Scale development and initial trust. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 19, 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, P.A. What drives electronic commerce? A theory of planned behavior perspective. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Denver, CO, USA, 2002; Volume 2002, pp. A1–A6. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, B.; Han, I. The impact of customer trust and perception of security control on the acceptance of electronic commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, K. Predicting user intentions: Comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Mykytyn, P.P.; Riemenschneider, C.K. Executive decisions about adoptin of information technology in small business: Theory and empirical tests. Inf. Syst. Res. 1997, 82, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, A.; Ulaga, W. Customer perceived value: A substitute for satisfaction in business markets. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2002, 17, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J. Customer satisfaction, service quality and perceived value: An integrative model. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S.P.; Tzempelikos, N.A.; Chatzipanagiotou, K. The relationships of customer-perceived value, satisfaction, loyalty and behavioral intentions. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2007, 6, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modeling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination. The Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J., Jr.; Brady, M.; Brand, R.R.; Hightower, R., Jr.; Shemwell, D.J. A cross-sectional test of the effect and conceptualization of service value. J. Serv. Mark. 1997, 11, 175–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Robertson, C.J. An exploratory study of service value in the USA and Ecuador’. Int. J. Ind. Manag. 1999, 10, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Magnusson, M.; Sjödén, P.O. Determinants of consumer behavior related to organic foods. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, S.; Rotsios, K.; Moshonas, G. Consumers’ purchase intentions towards Water Buffalo Milk Products (WBMPs) in the Greater Area of Thessaloniki Greece. Procedia. Econ. Financ. 2014, 9, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A. Determinants of Sustainable Food Consumption. Moving Consumers Down the Path of Sustainability by Understanding Their Behavior. Master’s Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.W.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Inf. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz De Maya, S.; López-López, I.; Munuera, J.L. Organic food consumption in Europe: International segmentation based on value system differences. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2005, 44, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes Personality and Behavior; The Dorsey Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Camino, J. Re-evaluating green marketing strategy: A stakeholder perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 1328–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvola, A.; Vassallo, M.; Dean, M.; Lampila, P.; Saba, A.; Lahteenmaki, L.; Shepherd, R. Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: The role of affective and moral attitudes in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2008, 50, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Hunter, J.E. Relationship among attitude, behavioral intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis of past research. Commun. Res. 1993, 20, 331–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Sayuti, N.M. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in halal food purchasing. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2011, 21, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.; Kupper, L.; Muller, K. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Analysis Methods; PWS-Kent Publishing Company: Boston, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, G.W.A.; Rusli, I.F.; Biak, D.R.; Idris, A. An application of the theory of planned behaviour to study the influencing factors of participation in source separation of food waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Herman, C.P.; Polivy, J. Consumption stereotypes and impression management: How you are what you eat. Appetite 2007, 48, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Personal. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, S.V.; Hansmann, R.; Scholz, R.W. Toward a sustainability label for food products: An analysis of experts’ and consumers’ acceptance. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2010, 49, 30–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giskes, K.; Van Lenthe, F.; Brug, J.; Mackenbach, J.; Turrell, G. Socioeconomic inequalities in food purchasing: The contribution of respondent-perceived and actual (objectively measured) price and availability of foods. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, S.; Petticrew, M.; Higgins, C.; Findlay, A.; Sparks, L. Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: Quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Fruit consumption determinants among young adults in Italy: A case study. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).