1. Introduction

Public spaces have played a special role since the beginning of urban living by manifesting the identity and function of towns and cities. In this respect, public spaces have a unique and timeless value. Public spaces have been a constant element in the structure of cities/towns and the lives of urban communities beginning from ancient times, through the Middle Ages, and in the modern era [

1]. European towns founded in the medieval period are particularly interesting in this respect. After the fall of the Roman Empire, numerous towns were established throughout Europe based on the antique principles of urban planning and organization [

2]. The urban layout was adapted to local conditions, but many towns had evolved from the existing human settlements and Roman military camps or they were built

in cruda radice (from a “raw root”). Towns were generally erected along or at the crossroads of major transportation routes and they formed a settlement network in the region. These towns had a regular network of perpendicular roads that separated densely developed districts, with a market square in the center [

3]. Market squares were the hubs of trading and commerce and they were the most important public spaces in towns.

A similar urbanization pattern can be observed in Warmia, a historical region in north-eastern Poland. The region’s settlement network is based on twelve towns that had been granted charters of incorporation in the Middle Ages [

4]. Olsztyn is the only settlement to evolved beyond the category of a small town [

5]. Warmian towns followed a similar pattern of development due to similarities in location, function, and, above all, spatial attributes. They have a regular urban layout dating back to the medieval period, but despite similar planning principles, considerable variations are noted between towns. The main differences are observed in the layout of transportation routes, the size and shape of market squares, and the location of public buildings. Historical buildings are the dominant feature in most towns and they constitute public spaces in downtown areas. The appearance and quality of these spaces are a testament to the dramatic events that took place in Warmia in the 20th century. At the end of World War II, Soviet troops embarked on a massive and premeditated campaign, aiming to destroy the historical architecture of Warmian towns. This political act served no military purpose, and it was undertaken solely to manifest the communist authorities’ resentment towards the origins and political status of Warmia. After the war, Warmian towns were rebuilt in line with the socialist realism doctrine [

6]. As a result, many historical town centers were deprived of their unique identity that had been shaped throughout the centuries. These historical facts set the directions for research into public spaces in Warmian towns. The functions of public spaces in historical market squares are evaluated in multicriteria analyses. These functions determine the quality of local life, which is influenced by the attractiveness of public spaces. The results of research studies are used to identify public spaces where revitalization measures are most needed to revive the economic, social, and cultural roles of downtown areas.

The absence of national and international standards for comprehensive evaluations of historical public spaces in small towns has prompted the authors to fill in this knowledge gap. The existing incidental reports usually focus on large cities and are adapted to their specific characteristics [

7,

8,

9]; therefore, they cannot be used as reference material for evaluating public spaces (historical market squares) in the centers of small towns. The proposed method is dedicated to small historical towns, and it is adapted to their unique attributes [

10,

11].

The present study was conducted in three towns in north-eastern Poland where historical architecture has been preserved to a varied degree. The evaluated towns were Dobre Miasto, Jeziorany, and Reszel, which are members of the Cittaslow International network. The Cittaslow movement was founded to improve the quality of urban life by promoting harmonious and sustainable development. The Cittaslow philosophy advocates the search for a healthy balance between economic growth, social development, and the protection of local traditions and cultural identity [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These values are upheld and popularized by all members of Cittaslow International. The urban fabric plays a very important role in sustainable development, and public spaces testify to a city’s attractiveness and its status on the regional scale.

The aim of this study was to analyze and evaluate historical public spaces in three towns in the region of Warmia in north-eastern Poland. The investigated public spaces are old market squares that are located the center of the studied towns. These historical landmarks shape the distinctive identity of Warmian towns and integrate members of the local community. Numerous factors determine the attractiveness of public spaces, their multifunctional character, and ability to satisfy diverse local needs, both material and spiritual. They include architectural factors (on the microscale), urban factors (on the macroscale), as well as the overall composition of these elements, which determines the esthetic and functional attributes of public spaces. The research goals were achieved with the use of a novel research method. The study involved multicriteria analyses and evaluations to identify factors that influence architectural design and directly stimulate the human senses. The results were used to assess the condition of public spaces in downtown areas (market squares) and to identify areas where revitalization programs are needed to revive community life and improve the functioning of public facilities. The study demonstrated that spatial order and harmonious urban development strongly influence perceptions of urban space, strengthen the local identity, and the architectural traditions of a region.

4. Results

The results of the study are based on the criteria for evaluating the spatial structure of historical towns, described in

Section 3. The results are presented separately for each stage of the conducted research, as in

Section 3.

Stage 1—Multicriteria analysis of the spatial structure of small towns.

The study revealed differences in the spatial structure of the analyzed towns. Because the towns have similar founding dates (Dobre Miasto—1329, Jeziorany—1338, and Reszel—1337), any correlations between the date of the town charter and urban design would be difficult to find. The studied towns have a grid street plan, which was the predominant urban layout in the Middle Ages. In Dobre Miasto and Jeziorany, an analysis of historical records revealed traces of urban design patterns typical of Silesia. In Silesian towns, the long sides of the market square were intersected by additional streets (

Figure 5a,b), which could suggest that the first settlers in the evaluated towns had originated from Silesia. The above pattern was not observed in Reszel (

Figure 5c). These findings indicate that the administrative boundaries of regions and countries did not act as barriers in the development of architecture and urban areas.

Topographic features exerted a considerable influence on the urban development pattern. All studied towns were built in cruda radice (from a “raw root”) but they were developed based on the existing settlements or military outposts. The urban layout of the analyzed towns relies on different natural features:

river bend—Reszel (33.3%),

fork at the junction of two rivers—Dobre Miasto (33.3%),

hill with steep slopes—Jeziorany (33.3%).

The urbanization process eradicated all traces of former settlements. In the Middle Ages, towns were established in areas with favorable terrain characteristics, which acted as natural defensive barriers to protect the inhabitants. Polish medieval towns were characterized by similar size, with the exception of large cities of strategic importance. The size of medieval towns reflected their economic status and technical capabilities. Considerable effort was required to build fortified walls, organize dense human settlements, and fulfill the basic needs of local communities. In successive centuries, economic growth led to the expansion of urban structures outside defensive walls. Despite the above, all towns have retained their historical centers. The territorial expansion of the analyzed towns is presented in

Table 7.

The data in

Table 7 point to a considerable increase in the area of the studied towns over the centuries. The density and type of urban structures changed in line with new trends in urban planning and architecture. However, the historical character of downtown areas was preserved, and these public spaces constitute landmarks that are clearly separated from contemporary urban structures.

Historical urban design plays an important role in public spaces, and it starkly contrasts with contemporary planning solutions in other parts of the town. Medieval towns had a grid pattern with a central market square surrounded by blocks of dense development. The homogeneity of urban design was additionally underscored by a regular network of roads that have survived to this day. The extent to which the medieval urban fabric has been preserved in illustrated in

Figure 6.

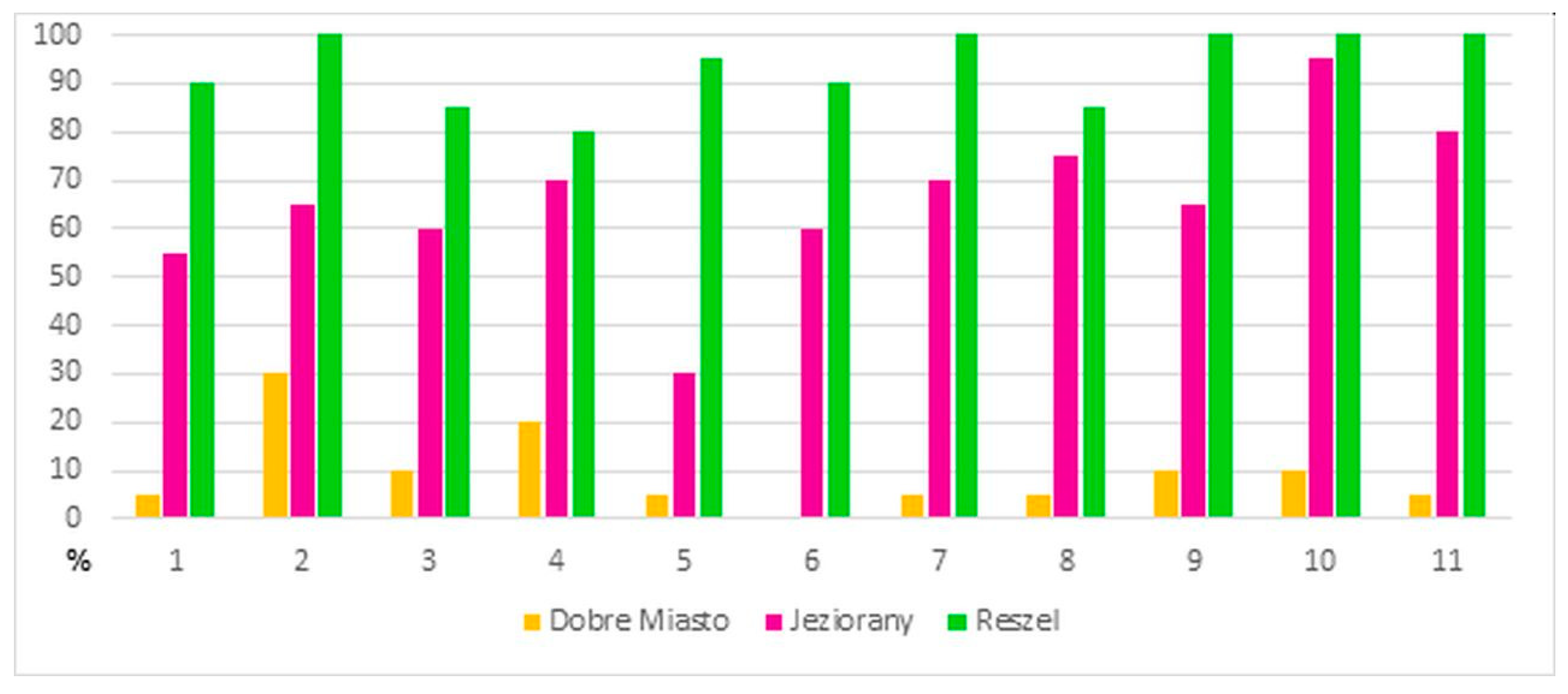

Key: 1—grid street pattern; 2—transport accessibility in public spaces; 3—road network; 4—boundaries of historical market squares; 5—shape and size of historical market squares; 6—dominant structure (architectural form); 7—scale and proportions of frontage buildings; 8—structures and facilities characteristic of downtown areas (market squares as public spaces); 9—types of development in historical market squares; 10—building materials forming the surface of the market square and roads; and 11—green infrastructure (secondary factor).

Historical market squares have been preserved as the main public spaces in medieval towns, regardless of the rate at which these towns had developed or their territorial reach. Market squares were the main trading places that contributed to the economic growth of medieval towns. Their shape and size had been designed to match the town’s layout at the time of foundation. The market square in Reszel has the shape of a square (33.3%), whereas Dobre Miasto and Jeziorany have rectangular market squares (66.6%). The area of the studied towns and market squares relative to the area enclosed by fortified walls (relative area of the market square) are presented in

Table 8.

The main public buildings that dominated the townscape, including the church, the town hall (in the center of the market square), and the fortified castle, were erected directly in the market square or in its vicinity. Very few of these buildings have survived the region’s turbulent history (wars, fires). In the group of the studied towns, all three buildings have been preserved only in Reszel.

In addition to public buildings and utilities, the quality of historical market squares is also influenced by the architectural style of the buildings flanking the square. Architectural factors influence esthetic perceptions of structures that define public spaces. The extent to which the original architecture of frontage buildings has been preserved is illustrated in

Figure 7.

Key: 1—historical architecture (preserved original design); 2—dominant buildings; 3—form and layout of urban development; 4—scale of development; 5—architectural composition of frontage buildings (subdivision of land parcels); 6—roof design and roofing materials; 7—building materials consistent with historical design; 8—architectural details; 9—texture and color of building facades; 10—structures and facilities characteristic of downtown areas (services, commerce, housing); and 11—distinctive atmosphere (genius loci) of public spaces.

Stage 2—urban planning and architecture as the main determinants of the quality of public spaces in historical towns.

The extent to which historical elements of public space have been preserved in the analyzed towns was evaluated in the second stage of the study. The influence of urban planning solutions and architectural features on historical market squares as the main public spaces was also evaluated, including the layout and area of market squares, historical architecture, and form and style of buildings flanking market squares. The extent to which the original spatial solutions have been preserved in downtown public spaces is illustrated in

Figure 8. The adopted criteria were evaluated subjectively on the following scale: 0–35%—not preserved; 36-65%—neutral; 66-85%—partly preserved; and 86–100%—preserved.

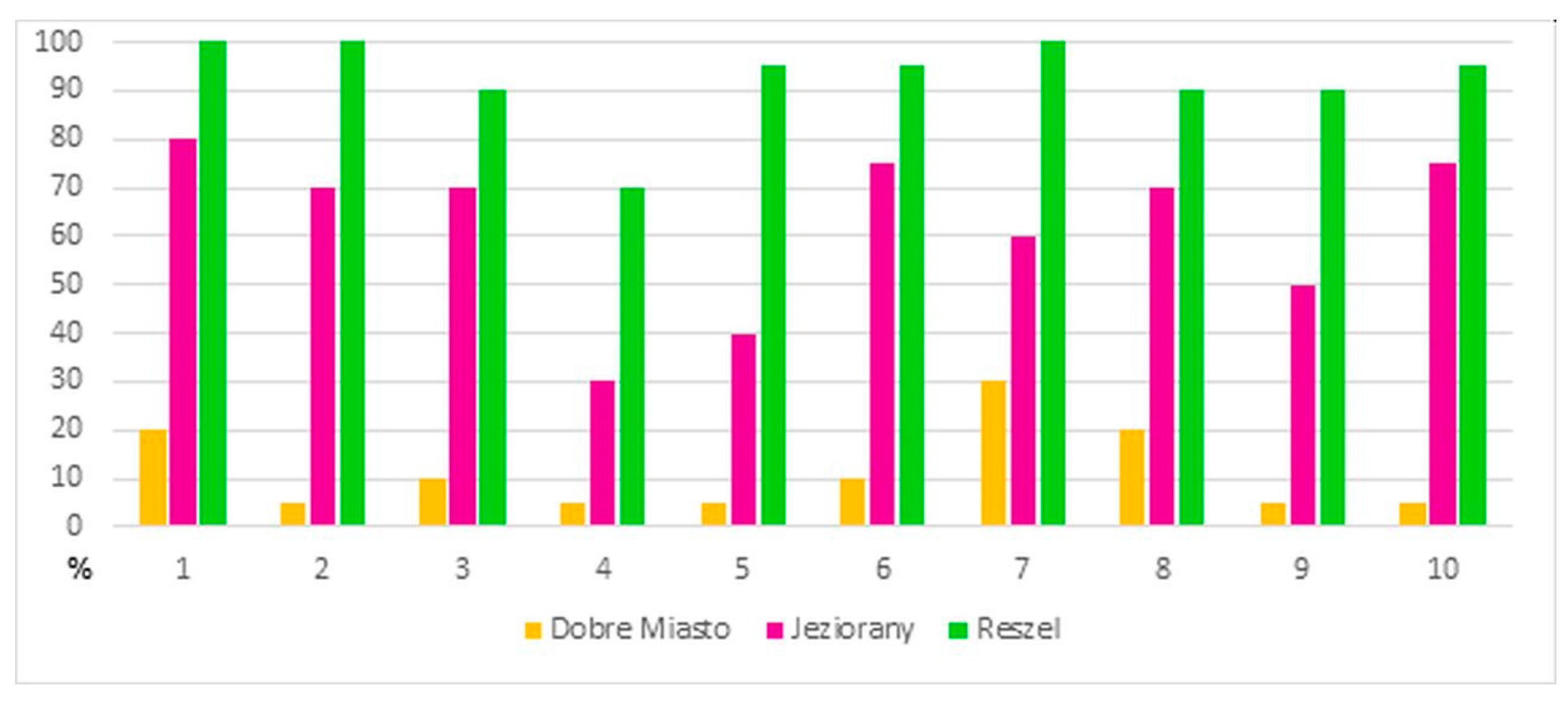

Key: 1—urban layout; 2—legible road network; 3—transport accessibility (pedestrian and vehicular traffic); 4—pedestrian safety (threats posed by wheeled traffic); 5—types of development in market squares; 6—identity of historical market squares; 7—dominant buildings; 8—density of development; 9—architecture of frontage buildings; and 10—historical dimension of public spaces.

Historical urban design and architectural solutions determine the value of public spaces in old towns. These factors should be also taken into account when heritage sites are adapted to modern needs. Historical structures differ from modern architecture, and the material and nonmaterial value of heritage sites should be adequately preserved. The variability of historical townscape elements is illustrated in

Figure 9. The adopted criteria were evaluated subjectively on the following scale: 0–35%—not preserved; 36–65%—neutral; 66-85%—partly preserved; and 86–100%—preserved.

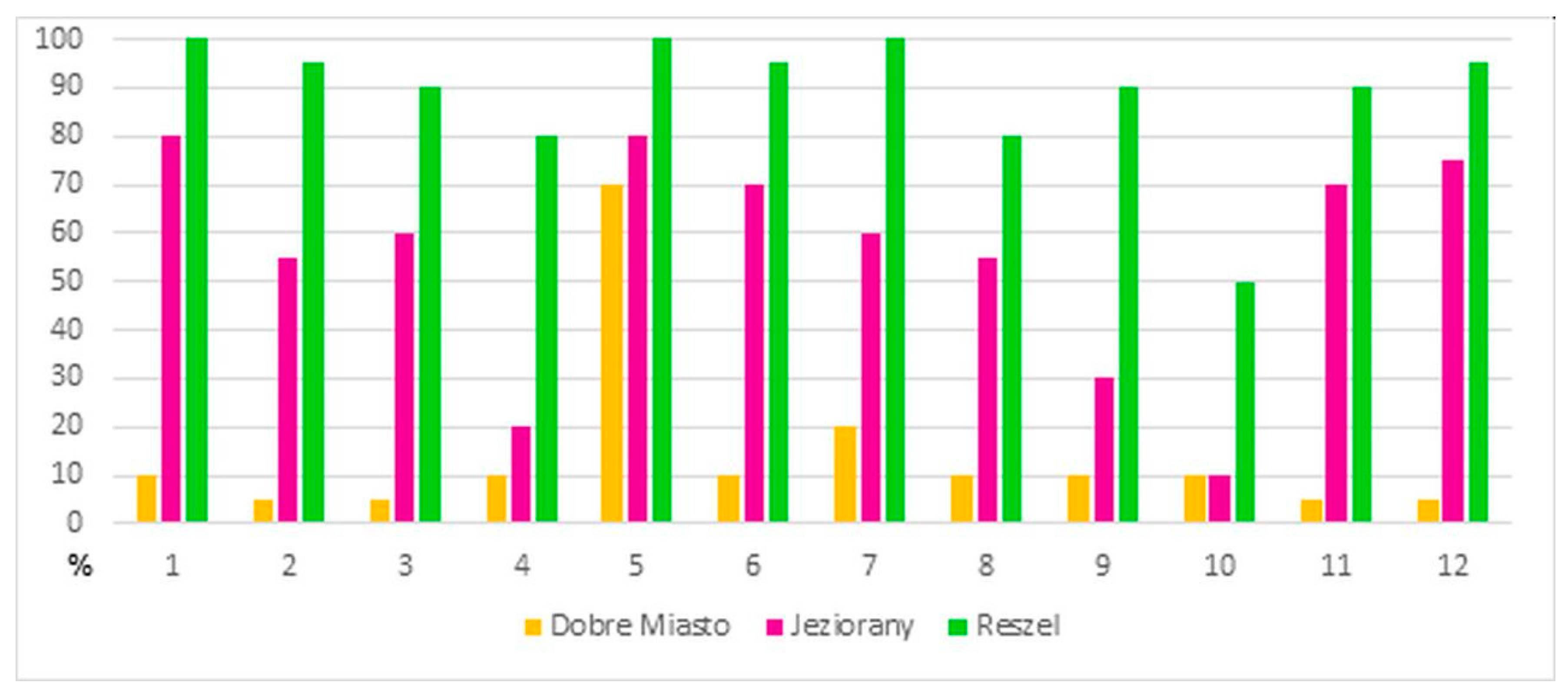

Key: 1—distinctive atmosphere—urban layout; 2—distinctive atmosphere—architecture; 3—structures and facilities characteristic of downtown areas; 4—functionality of historical spatial solutions; 5—density of development; 6—spatial order (esthetic perceptions, authentic historical experience); 7—stylistic homogeneity of urban structures; 8—availability of information; 9—pedestrian access; 10—disabled access; 11—potential for future development; and 12—distinctive atmosphere (genius loci) of public spaces.

5. Discussion

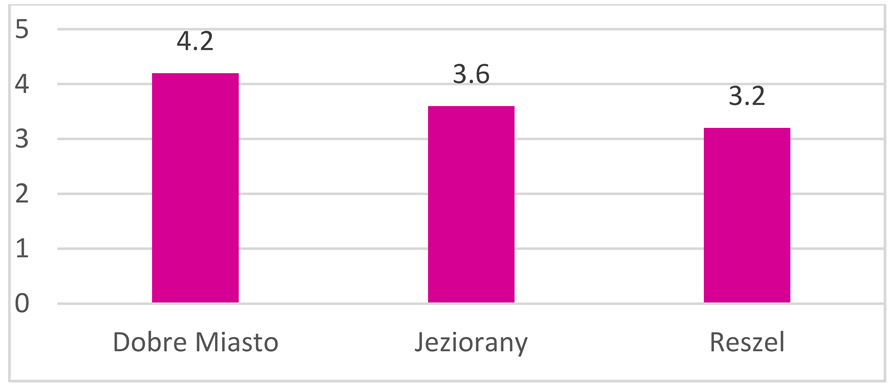

The results of spatial analyses demonstrated that urban elements that testify to the historical value of public spaces have been preserved to a varied degree in the studied towns. The applied research methods supported assessments of the influence of harmonious public space design on esthetic perceptions and the attractiveness of downtown areas in small historical towns. Urban, architectural, and compositional factors that significantly influence perceptions of the multidimensional character of public spaces were studied. The present condition of historical elements was evaluated. The results were used to identify areas where revitalization measures should be initiated to restore the attractiveness of historical centers and promote sustainable urban, economic, and social development [

68].

All three studied towns were founded in the first half of the 14th century. They were developed on a grid street plan, which was the predominant urban layout in medieval towns. The towns have a regular street pattern with a market square in the center. Different versions of the traditional grid pattern were encountered. The layout of Dobre Miasto and Jeziorany was visibly influenced by urban planning solutions typical of the region of Silesia in south-western Poland. The original elements of urban design have been preserved to a varied extent in the studied towns, and the degree of consistency with the historical layout was estimated at 5–20% in Dobre Miasto, 70–80% in Jeziorany, and 90–100% in Reszel.

Terrain characteristics played an important role during the establishment of medieval towns. These features acted as natural barriers that protected local inhabitants. The analyzed towns differed in this respect, and the predominant landforms included a river bend, a fork at the junction of two rivers, and a hill with steep slopes. These observations point to an individual approach to urban planning and a strong need for security.

The size of medieval towns was dictated by their economic status and technical capabilities. At the time of their establishment, the studied towns had an area of 4.5–6 ha. Their territorial reach continued to expand as their economic growth accelerated in successive centuries. Since their foundation, the analyzed towns increased three- to four-fold in size.

Market squares were the drivers of economic growth and social development in medieval towns. Located in the center, the market square was a hub of trade and commerce and the most important public space in the town. The market’s central location influenced development in the remaining parts of the town, and its size was determined by the area enclosed by the fortified wall. Dobre Miasto and Jeziorany have rectangular market squares, whereas Reszel has a square market. The market squares in the analyzed towns have a similar area of 0.37 to 0.58 ha. They are still the main public spaces in the evaluated towns but their functions have changed over time. Today, market squares play representative and recreational roles and they are regarded as hallmarks of local identity. The size of medieval market squares was determined by population, economic factors, and the town’s development pattern. In the analyzed towns, the average ratio of market area to town area was determined 8.83%, and it ranged from 7.5% to 10.5%. This observation confirms similar planning solutions in towns established in the corresponding period of time.

Continued economic growth increased the regional status and fueled the expansion of Warmian towns throughout the centuries. The area of Warmian towns increased rapidly in the 19th century when regional production plants such as brick factories, lumber mills, breweries, and flour mills were established in the region. The expansion of the railway network also significantly contributed to the economic growth and the territorial expansion of local towns [

69].

The cultural identity of public spaces in the analyzed towns was evaluated based on the extent to which the original urban planning elements have been preserved. The damage inflicted on Warmian towns at the end of World War II and the reconstruction effort undertaken after the war in line with the socialist realism doctrine contributed to significant differences in the historical character of old town centers. Original planning solutions and architectural features have been preserved to a different extent in the evaluated towns. A spatial analysis (

Figure 8) revealed that the historical urban fabric has been least well preserved in Dobre Miasto. The medieval church in the vicinity of the market square is the only remainder of the town’s nearly 700-year-old history. The market square in Jeziorany has been more successfully preserved. The current conservation status of the original urban layout and architecture in Jeziorany was evaluated as average. The historical urban fabric has been most successfully preserved in Reszel, which was not damaged during World War II.

The region’s history has directly affected the existing transportation network in the analyzed towns. Market squares are not closed off to vehicular traffic, and the market in Dobre Miasto is intersected by a main transit road to Poland’s border with the Kaliningrad Region. Based on the National Safety Risk Map and the results of field surveys, pedestrian safety has been evaluated at 5% in Dobre Miasto, 30% in Jeziorany, and 70% in Reszel. The high score noted in Reszel indicates that historical planning solutions can be successfully incorporated into the modern urban fabric.

The historical value of public spaces is determined mainly by the architecture of old town buildings. This factor is chiefly responsible for the emotional perceptions associated with historical heritage sites. The original urban fabric has been preserved to a different extent in the evaluated towns, and it was determined at 5% in Dobre Miasto, 50–75% in Jeziorany, and 90–95% in Reszel. The town hall, the church, and the fortified castle were the dominant buildings in medieval towns and they are the most important relics of these towns’ rich history. The conservation status and the impact of these structures on the contemporary townscape were evaluated at 30% in Dobre Miasto, 60% in Jeziorany, and 100% in Reszel. The extent to which the major buildings influence the historical identity of the studied towns was determined at 5–10% in Dobre Miasto, 75% in Jeziorany, and 95% in Reszel.

The value of public spaces is also influenced by their functional roles. Public spaces form the core of historical towns and determine their attractiveness for visitors. In the studied towns, the extent to which historical public spaces constitute the hubs of economic and social activity was determined at 5% in Dobre Miasto, 60% in Jeziorany, and 90% in Reszel. Dobre Miasto scored lowest in this respect because the market square is nearly entirely flanked by apartment blocks without retail or service outlets on the ground floor.

The results of the evaluation (

Figure 9) were used to assess the historical value of public spaces in small towns. The distinctive atmosphere of a place, referred to as genius loci in architecture, is the most elusive and subjective criterion in evaluations of historical sites. Historical sites have individual characteristics, but they constitute functioning central areas that are the key manifestations of local identity. The identity-building capacity of public spaces in the analyzed town was determined at 5–10% in Dobre Miasto, 55–80% in Jeziorany, and 95–100% in Reszel. These results coincide with the conservation status of the historical urban fabric and architecture in the studied towns, which suggests that these two components exert the greatest influence on the perceived attractiveness of historical public spaces.

The evaluated spatial elements and their role in the evolution and functioning of public spaces support the identification of urban structures and complexes that require restoration and revitalization. The results of the study were used to propose recommendations for enhancing the quality of public spaces in the analyzed towns (

Table 9). The solutions for improving the historical and functional attributes of public spaces in Warmian towns were formulated based on the key objectives of revitalization programs and the results of the current study.

The recommended revitalization measures can be an important tool in the process of shaping public spaces in the analyzed towns. They can significantly enhance the towns’ attractiveness for tourists and investors. For this reason, revitalization programs should focus on restoring the historical urban fabric, creating unrestricted pedestrian access to public spaces, reinstating the subdivision of land parcels, restoring historical architecture, reviving and increasing investment into downtown areas, and increasing the attractiveness of public spaces as the hubs of social activity and integration [

69]. Revitalization is a long-term process, which requires the participation of professionals from different areas of expertise who have a broad vision for future development. These efforts should also involve local community members because each town is a living and rapidly changing organism. Considerable research has been dedicated to the development and future outlook of historical towns. The open-design approach was implemented in Senigallia, Italy, to regenerate its historical urban heritage through the participatory design path [

70].

The most extensive revitalization measures are required in Dobre Miasto. The damage sustained during the war and postwar reconstruction efforts deprived the town of its historical identity. The market square in Dobre Miasto resembles a traffic junction, and it does not meet the definition of a user-friendly public space. Its urban layout and architecture do not make a reference to the town’s history, and the centrally located church is the only relic of the former medieval town that once surrounded it. The historical urban fabric of Jeziorany has been moderately preserved, and repair and renovation efforts are required to some extent. Revitalization is least urgently needed in Reszel. Spatial elements have a favorable conservation status, which contributes to the town’s socioeconomic growth. Therefore, the scope of the necessary revitalization is limited. The results presented in

Figure 9 and

Table 9 indicate that historical urban layout and architectural design are the key determinants of the perception of public spaces in terms of their contemporary attractiveness and functioning. These strong correlations contribute to a sense of local identity and responsibility for one’s place of residence.

6. Conclusions

This article analyzes and evaluates public spaces in small historical towns in the region of Warmia in north-eastern Poland. The original layout of the studied towns has been preserved to a varied degree in the course of their turbulent history, but old market squares continue to play the role of central points in the contemporary urban structure. Transformations of the urban layout and architecture of small towns affect spatial order and are closely associated with the economic growth and social development of downtown areas. Public spaces in the centers of historical towns have many dimensions and serve different purposes. For this reason, various aspects were taken into consideration in the presented analysis, including esthetic, economic, social, environmental, and functional factors, as well as sentimental value, which is an inseparable attribute of historical sites.

The results of the conducted analyses revealed that the historical character of public spaces has been preserved to a varied extent in the studied towns. The conservation status of the original urban fabric was evaluated as negative in Dobre Miasto, average in Jeziorany, and positive in Reszel. At the same time, a strong correlation was observed between the success of historic preservation and the contemporary functioning of public spaces in the examined towns. Dobre Miasto and Reszel are the extreme examples. The market square in Dobre Miasto has been completely deprived of its historical character and identity, and it no longer functions as a core that integrates members of the local community. In contrast, the historical urban fabric of Reszel has been largely preserved, and the town has a distinctive atmosphere that attracts both local residents and visitors. These observations provide strong evidence that medieval structures and architecture can be effectively incorporated into contemporary urban centers to accommodate local needs and the pace of modern life. The scope of the required revitalization measures differs in the analyzed public spaces. The results of this study can be used to identify areas that are in greatest need of revival and to define the extent of revitalization programs. The present findings also constitute valuable inputs for the local authorities and local communities in the process of prioritizing revitalization measures and enhancing the spatial value of historical centers in small towns.

In the future, the proposed method for evaluating the quality of historical public spaces will be validated based on the results of assessments conducted by other experts and local communities who are direct users of these spaces. These findings can be used to modify the presented methodological approach. This research study was motivated by the scarcity of global standards for evaluating public spaces in historical towns.